Background: HIV-infected T cells are quite resistant to apoptosis.

Results: Intracellular expression of HIV-1 Tat in T cells stabilized the mitochondrial membrane and reduced caspase activation mainly through NF-κB activation.

Conclusion: Intracellular Tat induced resistance to FasL-mediated apoptosis in T cells mainly through the second exon.

Significance: Tat-mediated protection against apoptosis may be a mechanism for HIV-1 persistence.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Fas, HIV-1, Mitochondrial Apoptosis, NF-κB, Anti-apoptotic Effect, Persistent Replication, Tat

Abstract

HIV-1 replication is efficiently controlled by the regulator protein Tat (101 amino acids) and codified by two exons, although the first exon (1–72 amino acids) is sufficient for this process. Tat can be released to the extracellular medium, acting as a soluble pro-apoptotic factor in neighboring cells. However, HIV-1-infected CD4+ T lymphocytes show a higher resistance to apoptosis. We observed that the intracellular expression of Tat delayed FasL-mediated apoptosis in both peripheral blood lymphocytes and Jurkat cells, as it is an essential pathway to control T cell homeostasis during immune activation. Jurkat-Tat cells showed impairment in the activation of caspase-8, deficient release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, and delayed activation of both caspase-9 and -3. This protection was due to a profound deregulation of proteins that stabilized the mitochondrial membrane integrity, such as heat shock proteins, prohibitin, or nucleophosmin, as well as to the up-regulation of NF-κB-dependent anti-apoptotic proteins, such as BCL2, c-FLIPS, XIAP, and C-IAP2. These effects were observed in Jurkat expressing full-length Tat (Jurkat-Tat101) but not in Jurkat expressing the first exon of Tat (Jurkat-Tat72), proving that the second exon, and particularly the NF-κB-related motif ESKKKVE, was necessary for Tat-mediated protection against FasL apoptosis. Accordingly, the protection exerted by Tat was independent of its function as a regulator of both viral transcription and elongation. Moreover, these data proved that HIV-1 could have developed strategies to delay FasL-mediated apoptosis in infected CD4+ T lymphocytes through the expression of Tat, thus favoring the persistent replication of HIV-1 in infected T cells.

Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is characterized by a continuous viral replication in CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages (1), leading ultimately to the development of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). This is caused by a progressive depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes through different mechanisms such as apoptosis, cellular syncytia, plasma membrane disruption by viral budding, or cytotoxicity by soluble viral proteins as Tat, Nef, and gp120 (2–4). Vpr may also have a cytotoxic effect on bystander or infected CD4+ T cells by increasing the mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (5–8), although it has also been described as an anti-apoptotic factor (9, 10). The programmed cell death or apoptosis of CD4+ T cells during HIV-1 infection is a complex process that affects differently both infected and uninfected cells. Apoptosis occurs mainly in bystander noninfected cells, whereas productively HIV-1-infected cells have evolved strategies to prevent or delay apoptosis in the context of immune activation (11–14).

HIV-1 regulator Tat induces apoptosis of bystander cells when is released to the extracellular medium as a soluble form (15). However, when Tat is expressed intracellularly, it produces the efficient elongation of the viral transcripts through the recruitment of the RNA polymerase II complex. Tat binds to a stem-loop RNA termed Tat-response element, located at the 5′ end of the nascent viral transcripts (16), and activates the recruitment of cellular elongation factors such as P-TEFb, increasing the processivity of RNA polymerase II (17). Tat is a 101-residue-long protein codified by two exons as follows: the first exon codifies amino acids 1–72, forming the transcriptionally active protein Tat72; and the second exon codifies amino acids 73–101 and overlaps with the env gene (18, 19). The Tat first exon (1–72 amino acids) contains the minimal functional domain to generate a protein competent in HIV-1 replication through a Tat-response element-dependent activation of the transcription, and the second exon (73–101 amino acids) has been described as dispensable for Tat activity (20). However, expression of the Tat second exon is conserved in all lentivirus, suggesting biological importance. In fact, the second exon is essential for Tat-mediated cell genome deregulation, thereby indicating that it may control the transcription of nonviral genes (Tat-response element-independent activation) (21–23), probably through binding to canonical enhancer sequences of cellular transcription factors such as NF-κB or Sp1 (24–26). This would indirectly affect the expression of several genes related to cellular functions such as T cell activation or apoptosis (15, 23, 27, 28). Moreover, the important contribution of Tat second exon to HIV-1 in vivo replication was demonstrated by the accidental infection of three laboratory workers with the HIV-1 HXB2 isolate, which shows a premature stop codon at the residue 89 (29, 30). In one of the infected patients, the HXB2 virus with first exon Tat reverted to second exon Tat (30), changing the mild course of the infection to a steep decline in CD4+ T cell count and a rapid progression to AIDS within 1 year (29). This unfortunate situation provided conclusive evidence for the biological requirement of the Tat second exon for HIV-1 replication and pathogenesis in vivo.

The role of Tat in apoptosis of bystander and infected cells is controversial because, although soluble Tat has been described as an inductor of apoptosis (15, 31, 32), it has also been proved to be a protector against apoptosis when it is expressed inside the host cell (28, 33). Our group demonstrated previously that intracellular Tat profoundly deregulates cellular gene expression, modifying the expression of genes involved in apoptosis (23). This deregulation was mainly due to the presence of the second exon, proving that although the first exon is sufficient for activating viral replication, full-length Tat should exert further control on HIV-1 pathogenesis by protecting the host cells against apoptosis. Apoptosis is essential to control T cell homeostasis, especially during the contraction of the immune response (34). As the antigen wanes, the number of T cells is appropriately reduced through the induction of apoptosis by Fas (CD95 or Apo-1), a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (35). Engagement of Fas receptor/CD95 with Fas ligand (FasL)/CD178 or Fas-activating antibodies (anti-CD95) recruits procaspase-8 to death-inducing signaling complex (DISC)4 through the FADD adapter protein. Within DISC, procaspase-8 is activated by dimerization and auto-cleavage (36–38). After that, Fas may activate apoptosis through two different pathways that distinguish type I and type II cells. Most cell types are classified as type I, where caspase-8 directly activates caspase-3, the main effector of the morphological and biochemical changes characteristic of apoptosis (36, 37). In type II cells, Fas receptors are excluded from lipid rafts and assemble DISC inefficiently upon activation of death receptors (39). Consequently, only a small fraction of procaspase-8 is activated; therefore, they require a subsequent amplification step through the mitochondrial cell death pathway. The mitochondria are highly involved in the induction of apoptosis in mammalian cells as they release to the cytosol many important factors that induce caspase activation and chromosome fragmentation after the permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane (40, 41). This mechanism is controlled by pro- and anti-apoptotic members of the BCL2 family such as the “BH3-domain only” protein Bid (42). Caspase-8-mediated cleavage of Bid initiates the mitochondrial cell death pathway (43–45) as truncated Bid (tBid) translocates to the mitochondrial membrane and triggers the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol (46). Cytochrome c participates then in the assembly of the apoptosome, a multiprotein complex required for caspase-9 activation that subsequently activates caspase-3 (47, 48).

Apoptosis is tightly controlled by many cellular proteins at different levels, and the final cell death occurs by imbalance between pro- and anti-apoptotic factors. One central regulator of cell survival and apoptosis is the transcription factor NF-κB that regulates the expression of anti-apoptotic genes such as BCL2, c-IAP, XIAP, as well as the cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) (49). Upstream in the apoptotic pathway, c-FLIP interferes with FasL-mediated activation through the binding to FADD and/or caspase-8/10 in a ligand-dependent manner, preventing DISC formation (50). There are three functional c-FLIP splice variants as follows: short form (c-FLIPS, 26 kDa) (51); intermediate or Raji form (c-FLIPR, 43 kDa) (52); and long form (c-FLIPL, 55 kDa) (53). c-FLIPS is exclusively a caspase-8 inhibitor, whereas c-FLIPL has dual function as caspase-8 inhibitor or activator, depending on the different ratios of c-FLIPL/caspase-8 (54). The mechanisms by which intracellular Tat interferes with apoptosis are not well known, although it has been described that Tat may enhance the expression of anti-apoptotic factors such as c-FLIP (33) or BCL2 (55, 56). The role of the second exon in the ability of Tat to protect against apoptosis is completely unknown.

It was determined that the intracellular expression of full-length Tat was able to delay Fas-mediated apoptosis in both PBLs and Jurkat and that this effect was due to the presence of the second exon. The mechanism of protection was based on the following: first on the deregulation of several NF-κB-dependent proteins, including the overexpression of BCL2 and c-FLIPS, and second on the preservation of the mitochondrial outer membrane integrity by several anti-apoptotic factors, delaying the release of cytochrome c and subsequent activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3. Getting further insight on this mechanism of protection against apoptosis in CD4+ T cells mediated by intracellular full-length Tat would provide a better understanding of the role of Tat in the ability of HIV-1 to create a persistent infection in the host.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells

PBLs were isolated from the blood of healthy donors by centrifugation through a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (GE Healthcare). Jurkat E6-1 cells were obtained from the AIDS Reagent Program, National Institutes of Health (57). Jurkat-Tat72 and Jurkat-Tat101 stably express, respectively, the HIV-1 Tat first exon (1–72 amino acids) or full-length Tat (1–101 amino acids) by using a Tet-Off system Clontech. Jurkat Tet-Off cells transfected with empty vector pTRE2hyg were used as negative control. Jurkat-Tat72 and Jurkat-Tat101 are not clones but are mixed populations in which more than 50% of the cells express high amounts of intracellular Tat101 or Tat72 protein. It was determined that the expression of Tat in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 was very similar to a real infection performed in MT-2 cells infected with the NL4.3WT strain (23). Both PBLs and Jurkat were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). In Jurkat-Tat cells, the culture medium was supplemented with 300 μg/ml geneticin (Sigma) and 300 mg/ml hygromycin B (Clontech).

Reagents and Antibodies

A monoclonal antibody against HIV-1 Tat (amino acids 2–9) was obtained from Advanced Biotechnologies Inc. (Columbia, MD). A monoclonal antibody against human Fas receptor (MBL International, Woburn, MA; clone SY-001) was used at 50 or 500 ng/ml during 4 or 18 h at 37 °C for inducing cell death in Jurkat or PBLs, respectively, and for quantifying the amount of Fas receptor on the cell surface by flow cytometry. A polyclonal antibody against procaspase 3 (p32) and active subunits p17 and p20 (clone H-277) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). A monoclonal antibody against procaspase 8 (p55) (clone 90A992) was also obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. A monoclonal antibody against procaspase 9 (p46) and active p35/p37 (clone 5B4) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Antibodies against BCL2 (clone C-2), Bid (clone 5C9), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) (clone 194C1439), c-FlipS/L (clone G-11), and p65/RelA (clone C-20) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The monoclonal antibody against cytochrome c was obtained from Calbiochem. A monoclonal antibody against β-actin (clone AC-15) was obtained from Sigma. Propidium iodide (PI) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were also obtained from Sigma. MitoTracker Red CMxRos mitochondrial probe was obtained from Lonza. Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488 and Alexa 546 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were purchased from GE Healthcare. Secondary IgG/IgM antibody fluorescein-conjugated (FITC) used in flow cytometry assays was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

Transient Transfection and Vectors

Resting PBLs and Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with an Easyjet Plus Electroporator (EquiBio, Middlesex, UK). In brief, 20 × 106 PBLs or 107 Jurkat were collected in 350 μl of RPMI 1640 medium without supplement and mixed with 1 μg/106 cells of plasmid DNA. Cells were transfected in a cuvette with a 4-mm electrode gap (EquiBio) at 340 V for PBLs and 280 V for Jurkat, 1500 microfarads, and maximum resistance.

pCMV-Tat72 tag or pCMV-Tat101 tag expression vectors were obtained by cloning Tat72 and Tat101, obtained from the pCMV-Tat101 vector (58), in pCMV tag (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Madrid, Spain), in NotI/BamHI. pNL4.3-TatM1I, which contains a point mutation in the start codon of the tat gene, was obtained from pNL4.3 wild-type (WT) vector (kindly provided by Dr. M. A. Martin (59)) by site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), using the following oligonucleotide: 5′-TCGACAGAGGAGAGCAAGAAATTGAGCCAGTAGAT-3′, which introduced a point mutation (underlined) in the start codon, changing a methionine by an isoleucine (supplemental Fig. 1). The presence of the selected mutation was confirmed by automatic sequencing. pNL4.3-TatM1I vector was co-transfected along with pCMV-Tat72 or pCMV-Tat101 in a ratio of 2:1. pEYFP-C1 vector (Clontech) was co-transfected as control of transfection efficiency and measured by flow cytometry.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated with RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Iberia, Madrid, Spain), and cDNA was synthesized by using the GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega), according to manufacturer's instructions. HIV-1 transcription was determined by quantitative PCR analysis of all viral mRNAs using the following primers directed against env/nef genes: P3 (5′-TTGCTCAATGCCACAGCCAT-3′) and P4 (5′-TTTGACCACTTGCCACCCAT-3′) (60). The expression of β-ACTIN was used as housekeeping gene to calculate the relative expression of env/nef genes. Primers for amplifying the human β-ACTIN gene were β-actin sense (5′-AGGCCCAGAGCAAGAGAGGCA-3′) and β-actin antisense (5′-CGCAGCTCATTGTAGAAGGTGTGGT-3′). SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used according to manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of Apoptosis

Cells were stained with 1.5 μm PI or annexin-V conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Immunostep, Salamanca, Spain), and fluorescence was measured by a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Clontech). Data were analyzed by CellQuest software. Cell viability was also determined by using the CellTiter-Glo® luminescent cell viability assay (Promega), following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 1× PBS, and resuspended in lysis buffer. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature to stabilize the luminescent signal, cell lysates were deposited in an opaque-walled multiwell plate and analyzed in an Orion microplate luminometer with Simplicity software (Berthold Detection Systems, Oak Ridge, TN).

Immunoblotting Assays

Nuclear and cytosolic protein fractions were obtained as described previously (61). Protein extracts were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose paper (GE Healthcare). After blocking and incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, proteins were detected by chemiluminescence with SuperSignal West Pico/Femto chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). Densitometry was performed in a Gel Doc 2000 System (Bio-Rad) by using Quantity One software. Gel bands were quantified, and background noise was subtracted from the images. The relative ratio of the optical density units corresponding to each sample was calculated regarding the internal control (β-actin) per each lane.

Immunofluorescence Assays

Living cells treated or not with anti-CD95 for 4 h were stained with MitoTracker and then adhered onto PolyPrep slides (Sigma) and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS. Immunofluorescence assays were then performed as described previously (23). Images were obtained with a Leica DMI 4000B Inverted Microscope (Leica Microsistemas, Barcelona, Spain).

Measurement of Caspase Activity

Activity of caspase-3/-7, -8, and -9 was measured with CaspaseGlo®3/7, CaspaseGlo®8, and CaspaseGlo®9 systems (Promega Biotech Iberica, Madrid, Spain), respectively. The luminescent signal (relative light units (RLUs)), which was directly proportional to caspase activation, was measured in an Orion microplate luminometer with Simplicity software (Berthold Detection Systems), and data were normalized according to the protein concentration in each sample.

Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Depletion

The release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria intermembrane space to the cytosol was measured by using InnoCyte flow cytometric cytochrome c release kit (Calbiochem). Briefly, 5 × 106 cells treated or not with FasL were permeabilized and then fixed with paraformaldehyde. After staining with a primary monoclonal antibody against cytochrome c and a secondary antibody conjugated with FITC, the measurement of cytochrome c release was performed by flow cytometry.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Gradient (ΔΨm)

ΔΨm was measured by flow cytometry using MitoProbe JC-1 assay kit (Molecular Probes), accordingly to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 2 × 106 cells/ml were incubated in JC-1 staining solution, and both green and red fluorescence were measured in FL1 and FL2 channels, respectively, by flow cytometry. The mitochondrial depolarization was calculated by measuring the decrease in the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio.

NF-κB Activation Assays

The ability of NF-κB to bind DNA was measured in nuclear protein extracts by DNA affinity immunoblotting assay, as described previously (23, 62). The quantity of NF-κB bound to DNA was detected by immunoblotting with a polyclonal antibody against p65/RelA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). As internal control, an input of nuclear protein for each sample was analyzed by using an antibody against β-actin (Sigma).

NF-κB transactivation activity was measured by transient transfection with p3κB-LUC vector, which contains a luciferase gene under the control of three -κB consensus sites from the immunoglobulin κ-chain promoter, as described before (23, 58). After incubation for 18 h, cell were treated or not with 50 ng/ml anti-CD95 for 4 h, and then the luciferase activity was measured by using luciferase assay system (Promega) in a Sirius luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RLUs were normalized with protein concentration in each sample and with the percentage of efficiently transfected cells by using pEYFP-C1 vector as transfection internal control.

Tat101 Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-specific mutagenesis of the 85ESKKKVE91 sequence necessary for Tat-mediated NF-κB activity, located in Tat second exon, was performed in the pTRE2hyg-Tat101 vector (28) by using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies), according to manufacturer's instructions. The following oligonucleotide was used to introduce selected mutations (underlined) in the 85ESKKKVE91 motif to generate the motif 85ESRVNVV91: 5′-AGACGGAATCGAGGGTGAACGTGGTGAGAGAGACAGAGACAGAT-3′. The presence of the selected mutations was confirmed by automatic sequencing.

Proteome Profiling

Two hundred micrograms of protein extracts were subjected to reduction and alkylation and then digested with trypsin (Promega) in 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.8. The resulting tryptic peptides were loaded into the liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system and analyzed by using a C-18 reversed phase nano-column (75-mm inner diameter × 25 cm, 3-mm particle size, Acclaim PepMap 100 C18, Thermo-Fisher) in a continuous acetonitrile gradient consisting of 0–30% B in 145 min, 30–43% A in 5 min, and 43–90% B in 1 min (A = 0.5% formic acid; B = 95% acetonitrile, 0.5% formic acid). A flow rate of ∼300 nl/min was used to elute peptides from the reverse phase nano-column to an emitter nanospray needle for real time ionization and peptide fragmentation on an orbital ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ Orbitrap XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific) (63). An enhanced resolution spectrum (resolution = 60,000) followed by the MS/MS spectra from the five most intense parent ions were analyzed during the chromatographic run (180 min). Dynamic exclusion was set at 0.5 min. For peptide identification, all spectra were analyzed with Proteome Discoverer (version 1.2, Thermo Fisher Scientific), using both Sequest (Thermo Fisher Scientific; version 1.0.43.2) (64) and Mascot search engines. For database searching, a Uniprot database was interrogated selecting the following parameters: trypsin digestion with two maximum missed cleavage sites, precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm, fragment mass tolerance of 1200 millimass units, carbamidomethylcysteine as fixed modification, and methionine oxidation, asparagine deamidation, and serine and threonine phosphorylation as dynamic modifications. For peptide and protein identification validation, results were loaded into Scaffold 3.0 software (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR), adding X!Tandem as an dditional search engine. Sequest search engine facilitates the “XCorr score” (values above 2.0), which measures how close the spectrum detected in the sample fits to the ideal spectrum. Differential expression in samples was determined using the quantity values of normalized spectra for each peptide, as determined by Scaffold software in a triplicate experiment. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm (65). Only those proteins involved in apoptotic pathways, cell survival, and mitochondrial function were selected for further analysis.

Antibody-based Apoptosis Microarray

RayBio human apoptosis antibody array kit (RayBiotech Inc., Norcross, GA) detects the relative level of 43 apoptosis-related proteins in cell lysates by using an array of antibodies spotted on a glass chip. Procedure was performed according to manufacturer's instructions. All microarrays were scanned under the same conditions in a ScanArray Express HT microarray scanner (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) using Alexa 555-specific filters. Images were quantified by QuantArray analysis software and a fixed circle segmentation algorithm. Data were filtered to discard those data points that were not considered positive with respect to the local background and the local negative controls. A second filtering round was done by removing from further analyses those proteins with less than three passing data points. Data were normalized against the positive controls of each array and then were mean-aggregated to result in a single value for each analyzed protein. Normalized data points where then logarithmically transformed for data compression and a better visualization of the results. Finally, logarithmic ratios (log2 ratios) against the reference data obtained from control cells were generated. Only proteins that were deregulated in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 versus Jurkat Tet-Off cells were represented.

Apoptosis-related Protein Networks

All proteins related to apoptosis that were deregulated were subjected to analysis with STRING 9.0 (66). Deregulated proteins were integrated in interconnected networks built by inputting the list of protein symbols, selecting Homo sapiens as organism and medium confidence, which does not consider interactions with combined scored under 0.4.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Corporations between control and FasL treatment groups were made using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni pos-test analysis to describe the statistical differences among groups. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant in all comparisons and were represented as *, **, or *** for p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001, respectively.

RESULTS

Apoptosis Induced by FasL Is Delayed in PBLs Transiently Transfected with Tat101 Alone or in the Context of HIV-1 Genome

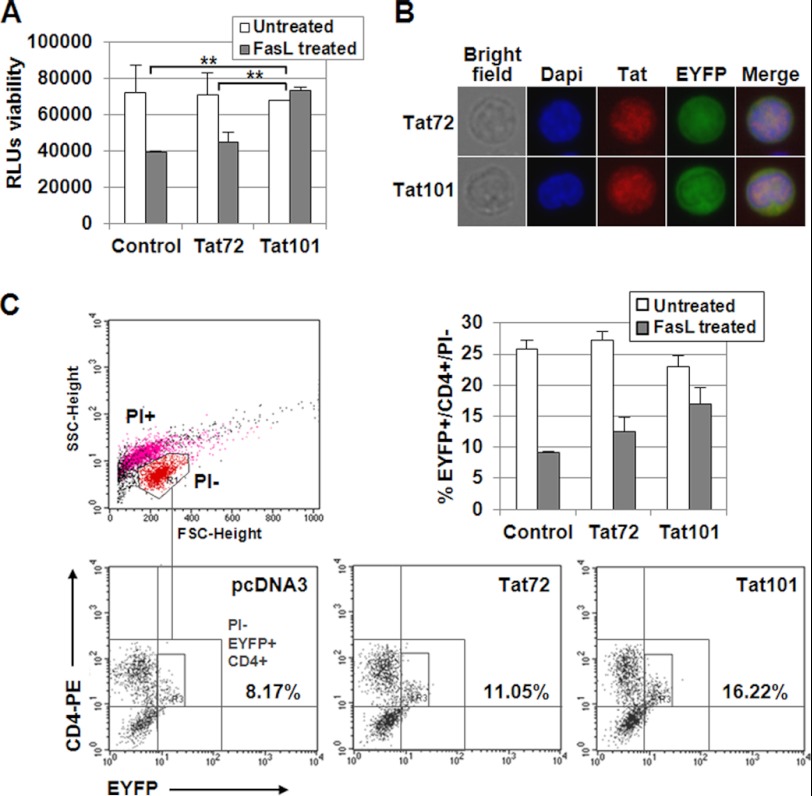

PBLs from healthy donors were transfected with pCMV-Tat101 or pCMV-Tat72 expression vectors. Transfection with pcDNA3 was used as negative control, and pEYFP-C1 was co-transfected in all cases as a control of transfection efficiency. Viability after transfection was 40–45% (data not shown), and transfection efficiency was 20–25%, depending on the batch of PBLs. Transfected PBLs were cultured for 3 days and then treated with FasL for 18 h. Viability was measured by chemiluminescence. Media from three different independent experiments are represented in Fig. 1A. It was observed that the intracellular expression of Tat101 in PBLs was able to exert 2.0-fold more protection against FasL-mediated apoptosis than control cells (p < 0.01), whereas Tat72 exerted lower protection. The efficient expression of Tat72 and Tat101 was assessed in EYFP+ cells by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1B), using DAPI to stain the nucleus, where most Tat was localized. To evaluate whether the resistance to apoptosis occurred mainly on CD4+ T cells, the transfected PBLs challenged with FasL for 18 h were stained with an antibody against CD4 conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE) and then analyzed by flow cytometry. PI− cells were gated and EYFP+/CD4+ cells were quantified within this group. It was determined that Tat101 alone was able to induce 2-fold more protection against FasL-mediated apoptosis than Tat72 or empty vector pcDNA3 in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

FasL-mediated apoptosis was reduced in PBLs expressing intracellular Tat101. A, resting PBLs were transiently transfected with pCMV-Tat72 or pCMV-Tat101 expression vectors or with pcDNA3 as negative control. pEYFP-C1 was used as control of transfection efficiency. PBLs were maintained for 3 days without stimulus, and then were treated with FasL for 18 h. Viability was measured by chemiluminescence. The bar diagram represents the media of three independent experiments, and lines on top of the bars correspond to the mean ± S.E. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni pos-test analysis was performed for statistical analysis; ** indicates p < 0.01. B, Tat expression and nuclear localization were confirmed by immunofluorescence. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. C, resting PBLs were transiently transfected with pCMV-Tat72 or pCMV-Tat101 expression vectors or with pcDNA3 as negative control. pEYFP-C1 was used as control of transfection efficiency. PBLs were maintained for 3 days without stimulus and then were treated with FasL for 18 h. Cells were stained with a monoclonal antibody against CD4 conjugated with PE and then with PI. Signals corresponding to EYFP, PE, and PI were analyzed by flow cytometry in FL1, FL2, and FL3 channels, respectively. SSC/FSC dot plot was used to select living (PI−) cells (region R1) as follows: red events correspond to PI−, living cells; magenta events correspond to PI+, dead cells; black events correspond to cellular debris. The numbers in the PI−/EYFP+/CD4+ dot plots show the percentage of CD4+/EYFP+ cells within the PI− region (region R3). The bar diagram represents the media of three independent experiments, and the lines on top of the bars correspond to the mean ± S.D.

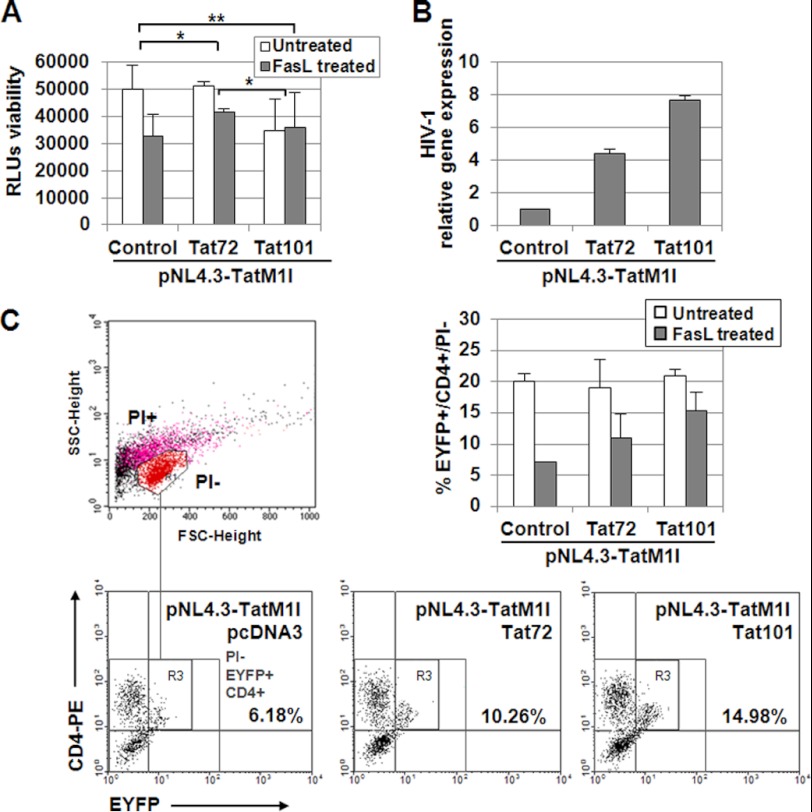

The role of Tat in the protection against FasL apoptosis was also evaluated in the context of viral replication. PBLs were transfected with the Tat-defective viral genome pNL4.3-TatM1I (described in supplemental Fig. 1) along with pCMV-Tat101 or pCMV-Tat72 expression vectors. Viability was measured by chemiluminescence, and it was determined that Tat101 produced 1.7-fold more protection against apoptosis induced by FasL than control cells (p < 0.01), whereas Tat72 exerted lower protection (Fig. 2A). HIV-1 replication was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2B). It was also evaluated whether the cells showing higher protection against apoptosis were CD4+ T cells. PBLs were then transfected with pCMV-Tat101 or pCMV-Tat72 expression vectors alone or along with pNL4.3-TatM1I, using pEYFP-C1 as control of transfection efficiency. As Tat is not known to be packaged inside the virions (67) and the viral genome NL4.3-TatM1I of the new generated virions did not produce Tat, only transfected cells would express the viral proteins encoded in the defective viral genome. After 3 days in culture, cells were challenged with FasL for 18 h and then stained with anti-CD4. As described above, the quantification of apoptosis was performed in EYFP+/CD4+ cells after selecting living PI− cells (Fig. 2C). The results obtained were quite similar to those when only Tat101 or Tat72 was expressed, proving that Tat was a significant viral protein in the induction of resistance to FasL-mediated apoptosis in infected CD4+ T cells, despite the presence of other viral proteins such as Nef, Vpr, or gp120.

FIGURE 2.

Tat101 reduced FasL-mediated apoptosis in HIV-1-transfected PBLs. A, PBLs were transfected with pNL4.3-TatM1I and pCMV-pTat72 or pCMV-Tat101 expression vectors. pcDNA3 was used as a negative control. pEYFP-C1 was used as a control of transfection efficiency. HIV-1 replication was allowed for 3 days before treatment with FasL for 18 h. Viability was measured by chemiluminescence. The bar diagram represents the media of three independent experiments, and lines on top of the bars correspond to S.E. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni pos-test analysis was performed for statistical analysis (* and ** indicates p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively). B, expression of HIV-1 genes was monitored by quantifying the expression of the env/nef genes by quantitative RT-PCR using β-ACTIN as internal control. C, resting PBLs were transiently transfected with pNL4.3-TatM1I and pCMV-pTat72 or pCMV-Tat101 expression vectors. pcDNA3 was used as negative control. pEYFP-C1 was used as control of transfection efficiency. PBLs were maintained for 3 days without stimulus and then were treated with FasL for 18 h. Cells were stained with a monoclonal antibody against CD4 conjugated with PE and then with PI. Signals corresponding to EYFP, PE, and PI were analyzed by flow cytometry in FL1, FL2, and FL3 channels, respectively. SSC/FSC dot plot was used to select living (PI−) cells (region R1) as follows: red events correspond to PI−, living cells; magenta events correspond to PI+, dead cells; black events correspond to cellular debris. The numbers in the PI−/EYFP+/CD4+ dot plots show the percentage of CD4+/EYFP+ cells within the PI− region (region R3). The bar diagram represents the media of three independent experiments, and the lines on top of the bars correspond to S.D.

FasL-mediated Apoptosis Is Delayed in Jurkat Cells with Transient or Stable Expression of Tat101 or Tat72

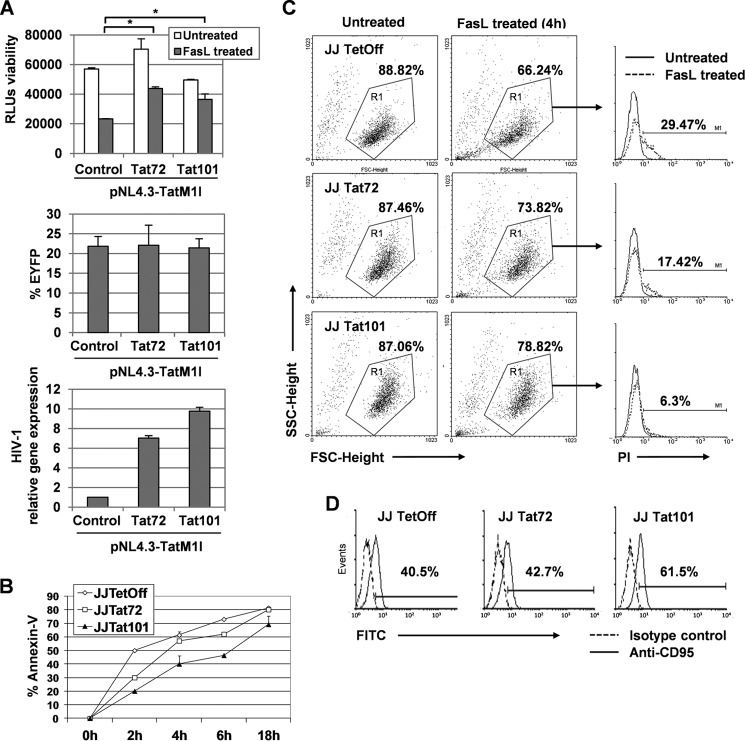

As a model of CD4+ T cells was necessary to dissect the mechanism of action of Tat to exert protection against FasL-mediated apoptosis, the potential use of Jurkat cells for this purpose was evaluated. Jurkat E6-1 cells were transiently transfected with the Tat-defective viral genome pNL4.3-TatM1I along with pCMV-Tat101 or pCMV-Tat72 expression vectors. Transfection with pcDNA3 was used as negative control, and pEYFP-C1 was co-transfected as control of transfection efficiency, which was 20–25% in all cases. HIV-1 replication was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. Efficient expression of Tat72 and Tat101 was assessed by immunofluorescence (data not shown). Transfected Jurkat cells were cultured for 3 days and then treated with FasL for 4 h. Cell viability was measured by luminometric assay, and the media of three different independent experiments were represented as a ratio of the apoptosis induced in FasL-treated PBLs regarding untreated cells (Fig. 3A, 1st bar diagram). It was observed that the intracellular expression of Tat101 in Jurkat cells produced 1.8-fold more protection against FasL-mediated apoptosis than control cells, whereas Tat72 exerted lower protection (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Tat101 reduced FasL-mediated apoptosis in HIV-1-transfected Jurkat cells and in Jurkat cells with stable expression of intracellular Tat101. A, Jurkat E6-1 cells were transfected with pNL4.3-TatM1I together with pCMV-Tat72 or pCMV-Tat101 expression vectors. pcDNA3 was used as negative control. pEYFP-C1 was used as control of transfection efficiency. After 3 days in culture, cells were treated with FasL for 4 h. Viability was measured by chemiluminescence. The bar diagram represents the media of three independent experiments, and lines on top of the bars correspond to S.E. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni pos-test analysis was performed for statistical analysis (* indicates p < 0.05). HIV-1 replication was monitored by quantifying the expression of the env/nef genes by quantitative RT-PCR using β-ACTIN as internal control. B, Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells were treated with FasL for 2, 4, 6, and 18 h and then stained with annexin-V-FITC to measure by flow cytometry the percentage of apoptotic cells. C, Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells were treated with FasL during 4 h and then stained with PI. The induction of apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry. Region R1 was used to select the living PI− cells in the groups of untreated cells, displayed as SSC/FSC dot plots. The percentage of apoptotic cells (PI+) was determined within R1 in treated cells and then represented as histograms where the basal cell death (continuous line) was compared with the apoptosis induced after treatment with FasL (discontinuous line). The numbers shown correspond to the percentage of apoptotic cells within R1 after subtracting the basal death. D, Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells were stained with a monoclonal antibody against Fas receptor (FasR/CD95) and a secondary antibody conjugated with FITC. The percentage of cells expressing Fas was measured by flow cytometry. The histograms compare the isotype control (discontinuous line) with the expression of FasR (continuous line) on the cell surface. Numbers shown are the percentage of cells expressing CD95 after subtracting the isotype control. All data shown are media or representative of three independent experiments.

To dissect the mechanism underlying intracellular Tat-mediated protection against apoptosis by FasL in T cells, the use of Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 stable cell lines was analyzed. Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 were treated with FasL at different times, and early apoptosis was measured by annexin-V-FITC staining (Fig. 3B). Flow cytometry analysis showed that the percentage of pro-apoptotic cells was 1.8-fold lower on average in Jurkat Tat101 than in control cells, whereas this percentage in Jurkat Tat72 was 1.2-fold lower on average than control. Measurement of apoptosis by PI staining in Jurkat-Tat72 and Jurkat-Tat101 treated with FasL for 4 h showed that Tat101 delayed 4.6-fold the induction apoptosis, whereas Tat72 delayed apoptosis 1.7-fold (Fig. 3C). The expression of Fas receptors/CD95 on the cell surface was increased by 20% in Tat101, but Tat 72 did not produce significant changes (Fig. 3D).

FasL-mediated Activation of Caspase-8 and -3 Is Decreased in Jurkat-Tat101 Cells

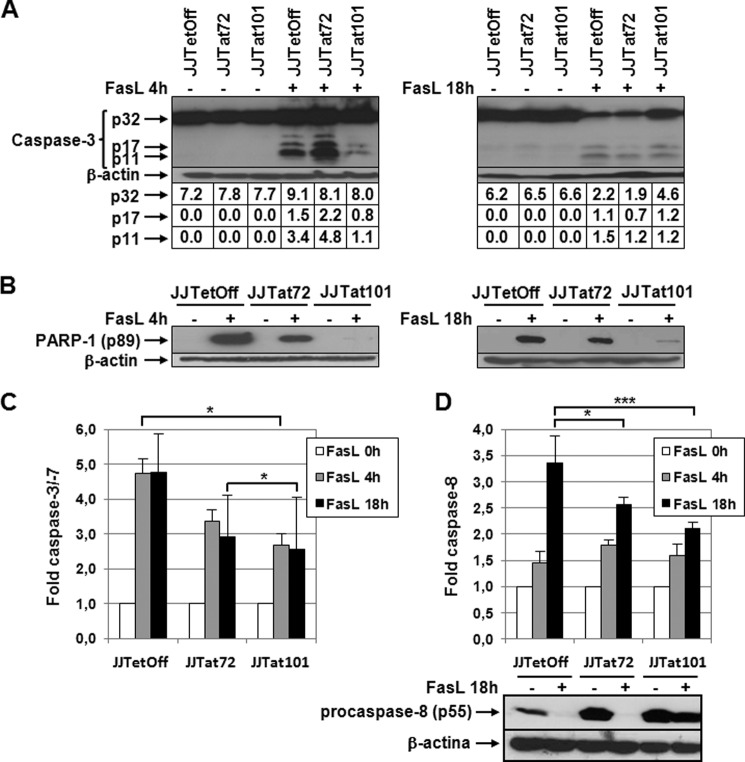

Cleavage of procaspase-3 was analyzed by immunoblotting in protein extracts obtained from Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated with FasL for 4 or 18 h. As shown Fig. 4A, the active subunits p17 and p11 were rapidly generated in Jurkat-Tat72 and control cells after treatment with FasL for 4 h. After 18 h of treatment, the cleavage of caspase-3 was also initiated in Jurkat-Tat101, although 2-fold more of high quantity unprocessed precursor p32 could also be observed in these cells.

FIGURE 4.

Activation of caspase-3 and -8 was impaired in Jurkat-Tat101 treated with FasL. A, procaspase-3 cleavage was analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody against procaspase-3 (p32) and active fragments p17/p11 in protein extracts obtained from Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated or not with FasL for 4 or 18 h. β-Actin was used as internal loading control. Gel bands were quantified by densitometry, and the background noise was subtracted from the images. The relative ratio of the optical density units corresponding to each sample was calculated regarding the internal control (β-actin) per each lane. B, cleavage of PARP-1 was analyzed by using a monoclonal antibody against the cleaved fragment p89. β-Actin was used as loading control. C, caspase-3/-7 activation was measured by chemiluminescence in cells treated or not with FasL. D, caspase-8 activation was measured by chemiluminescence in cells treated or not with FasL. Levels of procaspase-8 were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody against procaspase-8 (p55) in protein extracts obtained from Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated with FasL for 18 h. β-Actin was used as internal loading control. The bar diagrams show the media of relative RLUs fold from three independent experiments, and the lines on the top of the bars represent the S.D. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test analysis was performed for statistical analysis. * and *** indicate p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.

To further evaluate the activation of caspase-3 in Jurkat-Tat cells treated with FasL, the cleavage of the caspase-3 substrate PARP-1 was analyzed by immunoblotting. PARP-1 cleaved from p89 was abundantly detected in the cytoplasm of control cells treated with FasL for 4 h, but it was only weakly produced in Jurkat-Tat101 even after treatment for 18 h (Fig. 4B). In Jurkat-Tat72, the levels of cytosolic p89 were halfway between those detected in Jurkat-Tat101 and control cells. Measurement of caspase-3/-7 activity showed that the activation of these caspases in response to FasL was delayed in Jurkat-Tat101 regarding Jurkat-Tat72 and control cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4C). Measurement of the activation of caspase-8 showed 1.6-fold reduction in Jurkat-Tat101 (p < 0.001), whereas the difference between Jurkat-Tat72 and control cells was lower (Fig. 4D). The cleavage of caspase-8 by immunoblotting showed in Jurkat-Tat101 a great delay in the cleavage of procaspase-8 (p55) after treatment with FasL for 18 h. This was not observed in Jurkat-Tat72.

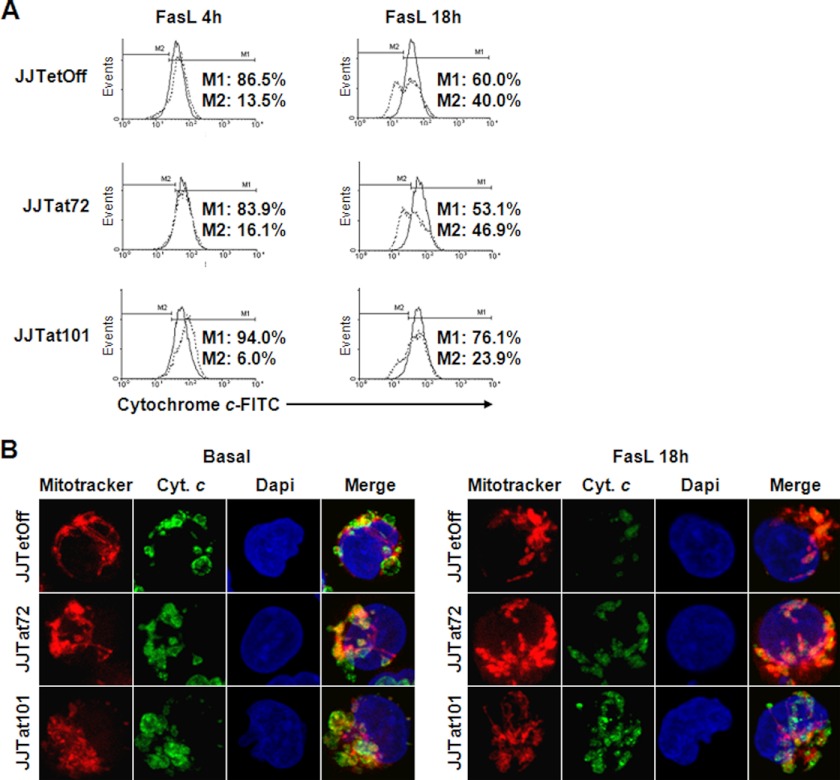

Release of Cytochrome c and Activation of Caspase-9 Are Impaired in Jurkat-Tat101 Cells Due to High Stability of the Mitochondrial Inner Membrane Electrochemical Potential

Analysis by flow cytometry showed that the release of cytochrome c to the cytoplasm from the mitochondrial intermembrane space in response to treatment with FasL for 4 or 18 h was reduced nearly 2-fold in Jurkat-Tat101 cells, whereas no significant difference with control cells was observed in Jurkat-Tat72 cells (Fig. 5A). These results were confirmed by confocal microscopy through the analysis of the subcellular localization of cytochrome c (Fig. 5B). Consistent with data obtained by flow cytometry, the mitochondria of Jurkat cells with stable expression of Tat101 were more resilient to release cytochrome c in response to FasL. Besides, the mitochondria of Jurkat-Tat101 cells showed a more diffuse and less compact distribution than those in Jurkat-Tat72 and control cells.

FIGURE 5.

Release of cytochrome c induced by FasL was reduced in Jurkat-Tat101. A, release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria was quantified by flow cytometry in Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated or not with FasL during 4 or 18 h. The histograms correspond to one representative experiment out of three and compare the percentage of cytochrome c that was retained in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (continuous line; marker M1) versus the cytochrome c released after treatment with FasL (discontinuous line; marker M2). B, release of cytochrome c (Cyt. c) was analyzed by immunofluorescence. After staining with the Mitotracker probe, the cells were fixed and stained with a monoclonal antibody against cytochrome c and a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa 488. The nucleus was stained with DAPI.

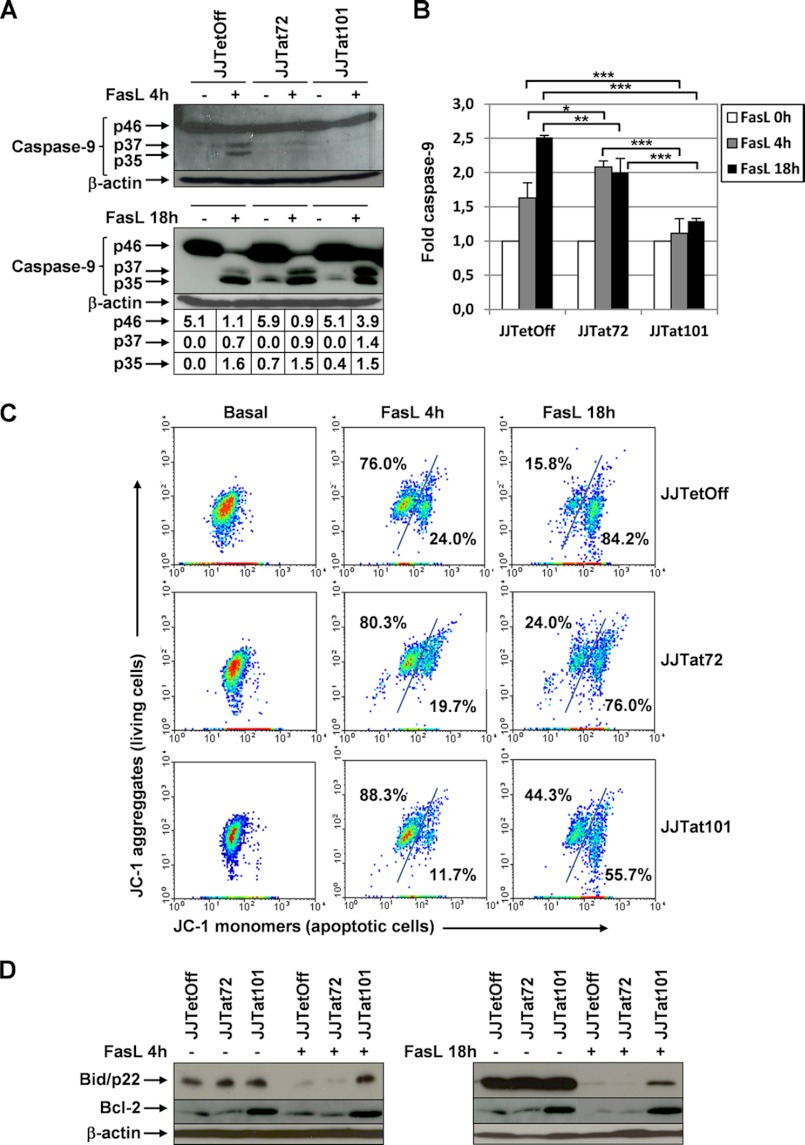

Cytosolic protein extracts for Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated with FasL for 4 or 18 h were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody against precursor p46 and active forms p37/p35 of caspase-9. As shown Fig. 6A, p37/p35 were only detected in control cells and weakly in Jurkat-Tat72 cells after treatment with FasL for 4 h, but no band corresponding to the activation of caspase-9 was observed in Jurkat-Tat101. After 18 h, p37/p35 were detected in the cytosol of Jurkat-Tat101, but there was 3.5-fold more unprocessed procaspase-9 than in control cells, proving that the impaired release of cytochrome c in these cells resulted in a delayed activation of caspase-9. This deficient caspase-9 activation was confirmed by measuring the activity of caspase-9 by chemiluminescence, which was 1.7-fold lower in Jurkat-Tat101 cells (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Jurkat-Tat101 showed a reduced cleavage of Bid and procaspase-9, overexpression of BCL2, and higher stability of the mitochondrial inner membrane potential. A, cleavage of procaspase-9 was analyzed by immunoblotting in cytosolic protein extracts obtained from Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated or not with FasL during 4 or 18 h, using an antibody against the procaspase-9 (p46) and active caspase-9 (p37/p35) fragments. β-Actin was used as loading control. Gel bands were quantified by densitometry, and the background noise was subtracted from the images. The relative ratio of the optical density units corresponding to each sample was calculated regarding the internal control (β-actin) per each lane. B, caspase-9 activity was measured by chemiluminescence. The bar diagram shows the media of relative RLUs fold from three independent experiments, and the lines on the top of the bars represent the S.D. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test analysis was performed for statistical analysis, and *, **, and *** correspond to p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001, respectively. C, mitochondrial membrane potential gradient (ΔΨm) was measured by flow cytometry using the lipophilic dye JC-1. Red fluorescent aggregates in the undamaged mitochondria were represented in a dot plot versus the green fluorescent monomers dispersed through the cytosol. The numbers upper left in the diagrams represent the cells with stable mitochondrial membrane integrity; the numbers lower right represent the loss of mitochondrial membrane integrity. A representative experiment out of three is shown. D, expression of BCL2 and Bid (p22) was analyzed by immunoblotting, and β-actin was used as loading control.

The mitochondrial membrane potential gradient (ΔΨm) was measured by using the cationic lipophilic dye JC-1 (68). The dispersion of green JC-1 monomers from the mitochondria throughout the entire cell, which correlates with the induction of apoptosis, was measured by flow cytometry after treatment with FasL for 4 or 18 h (Fig. 6C). The population of Jurkat-Tat101 cells committed to apoptosis, low ΔΨm and higher monomeric JC-1 with green fluorescence, was smaller than in Jurkat-Tat72 and control cells after treatment with FasL. This difference was mainly observed after 18 h of treatment, where nearly 30% of Jurkat-Tat101 cell population showed high resistance to lose the mitochondrial membrane potential, regarding control cells. In accordance, the population of living cells with higher ΔΨm, where JC-1 formed aggregates with red fluorescence, was also 2.8-fold greater in Jurkat-Tat101. Jurkat-Tat72 cells showed an intermediate profile of mitochondrial membrane integrity loss with 1.8-fold higher ΔΨm than control cells. As a result, the mitochondrial depolarization, measured by the decrease in the red/green fluorescence intensity ratio, was delayed by the intracellular expression of Tat101 and, with less intensity, by Tat72.

Analysis by immunoblotting of BCL2 showed that the expression was enhanced in Jurkat-Tat101 in basal conditions, and its quantity was not significantly reduced even after treatment with FasL during 18 h (Fig. 6D). The expression of Bid (p22) diminishes as caspase-8 cleaves it to generate the truncated form tBid/p15 that translocates to the mitochondria and directly induces the outer membrane permeabilization (43). The expression of Bid/p22 was significantly reduced in Jurkat-Tat72 and control cells after treatment with FasL, suggesting that tBid was being synthesized and translocated to the mitochondrial membrane. However, Bid/p22 remained uncleaved in Jurkat-Tat101, proving that the activation of caspase-8 was deficient in these cells.

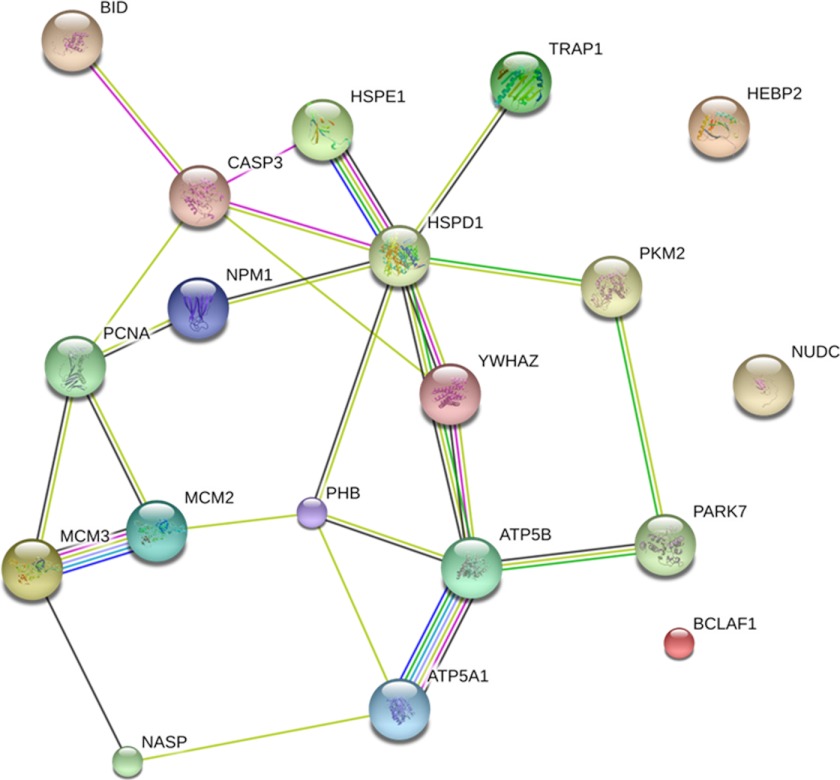

Tat Deregulates the Expression of Cellular Proteins Related to Apoptosis and to the Maintenance of Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Integrity

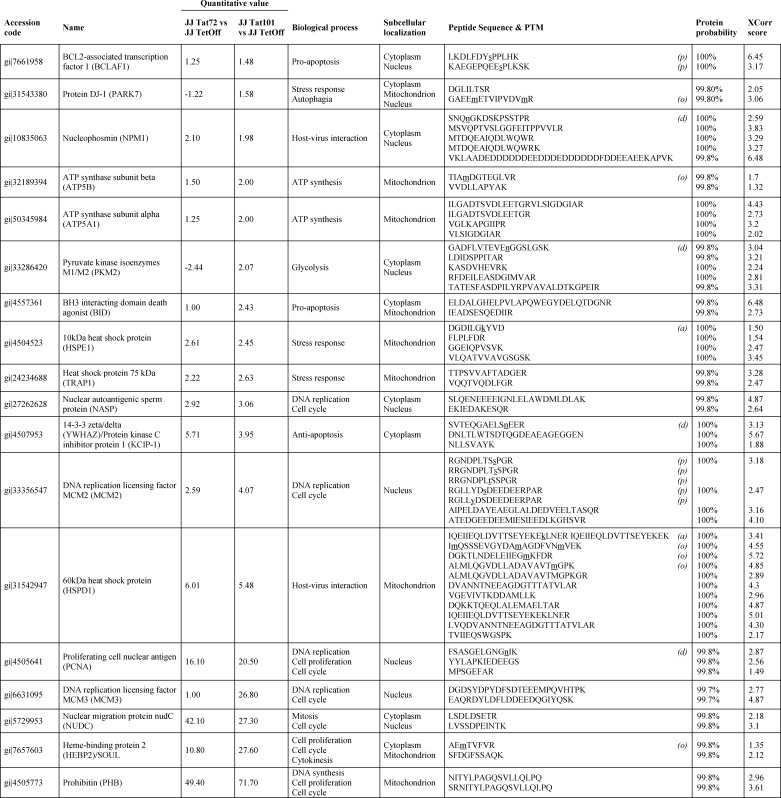

The whole proteome of Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells was analyzed by LC-MS/MS in basal conditions. The analysis showed that Tat mostly induced the up-regulation of proteins related to the cell cycle and proliferation such as PHB, HEBP2/SOUL, NUDC, MCM2/3, PCNA, and NASP (Table 1). The expression of most of these proteins was more enhanced by the expression of Tat101 than Tat72. Besides, proteins related to apoptosis and stress response were also up-regulated by Tat, such as 14-3-3ζ/δ, Bid, DJ-1/PARK7, and several heat shock proteins. More than 50% of the apoptotic proteins deregulated were related to the mitochondrial function, including ATP synthase α and β subunits, which were mainly enhanced by the expression of Tat101. Most of these proteins belong to interconnected cellular pathways, and in some cases their activation was related to caspase-3 activity. This was observed after analyzing the predicted protein interactions by STRING 9.0 database. As shown Fig. 7, caspase-3 was directly connected to Bid, HSPE1, HSPD1, YWHAZ, and PCNA. In turn, these proteins were connected with the other proteins whose expression was modulated by Tat, forming an intertwined network that included mostly all deregulated proteins.

TABLE 1.

Selected proteins differently expresse and detected by mass spectrometry in protein extracts from Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 cells, in comparison with Tet-Off cells

Amino acidic residues with post-translational modifications (PTMs) are underlined and in lowercase. PTMs detected were as follows; p, phosphorylation; a, acetylation; d, deamidation; and o, oxidation.

FIGURE 7.

Network of predicted interactions between proteins related to apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane integrity, as specified in Table 1, the expression of which was modified in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 versus control cells. Medium confidence score level was 0.400. Caspase-3 was included to evaluate its central point in the network. Data supporting protein-protein interactions were derived from experimental studies (dark purple lines), homology (light purple lines), databases (light blue lines), text mining (light green lines), concurrence (dark blue lines), and co-expression (black lines). Node color is arbitrary.

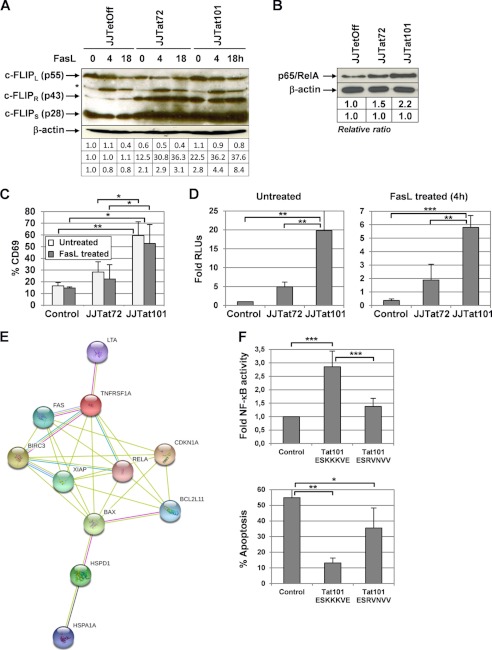

Intracellular Tat101 Deregulates Several NF-κB-dependent Proteins Involved in the Control of Apoptosis

The expression of c-FLIPL/S was analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 8A). c-FLIPS, rather than c-FLIPL, which is the one that confers resistance to human T cells against Fas-mediated apoptosis (69), was 2.1- and 2.8-fold enhanced in Jurkat-Tat72 and Jurkat-Tat101 in basal conditions. Treatment with FasL for 18 h reduced the expression of c-FLIPL similarly in all cell types, but the expression of c-FLIPS was very different depending on the expression of Tat or the treatment with FasL. Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 showed 10.5- and 3.8-fold more c-FLIPS expression than control cells, respectively, after treatment with FasL for 18 h. However, the expression of c-FLIPR/p43 was enhanced 22.5- and 12.5-fold more in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72, respectively, than in control cells, in basal conditions. After treatment with FasL, the cleavage of c-FLIPL to c-FLIPR/p43 was increased 30-fold more in both Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 (see supplemental Fig. 2).

FIGURE 8.

NF-κB-dependent proteins involved in the control of apoptosis were up-regulated in Jurkat-Tat101. A, expression of c-FLIPL (55 kDa), c-FLIPR (43 kDa), and c-FLIPS (28 kDa) isoforms was analyzed by immunoblotting in cytosolic protein extracts from Jurkat-Tat101, Jurkat-Tat72, and control cells treated or not with FasL for 4 or 18 h. β-Actin was used as loading control. B, NF-κB activity was analyzed in basal conditions by using DNA affinity immunoblotting assay. Gel bands were quantified by densitometry, and the background noise was subtracted from the images. The relative ratio of the optical density units corresponding to each sample was calculated regarding the internal control (β-actin) per each lane. C, Jurkat-Tat72, Jurkat-Tat101, and control cells were treated with FasL during 4 h and then stained with an antibody against CD69 conjugated with PE. The percentage of cells expressing CD69 on the cell surface was measured by flow cytometry. The bar diagram represents the percentage of cells expressing CD69 after subtracting the isotope control. D, NF-κB-dependent transactivation activity was measured by transient transfection of vector p3κB-LUC. Fold mean of RLUs corresponding to three independent experiments is represented, and lines on the top of the bars correspond to S.D. E, network of proteins related to apoptosis and identified by antibody-based microarray (see Table 2), expression of which was modified in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 versus control cells. Predicted protein-protein interaction was obtained using a medium confidence score level (0.400). Data supporting protein-protein interactions derived from experimental studies (reddish purple lines), homology (light purple lines), databases (light blue lines), text mining (light green lines), and co-expression (black lines). The color of the nodes is arbitrary. F, Jurkat Tet-Off cells were transiently co-transfected with p3κB-LUC vector and pTRE2hyg-Tat101 ESKKKVE (wild type), pTRE2hyg-Tat101 ESRVNVV (mutated), or pTRE2hyg empty vector as negative control. After 18 h, NF-κB activity was measured by chemiluminescence. Fold of relative RLUs regarding the control cells are represented (upper bar diagram). Cells were then treated with FasL for 4 h, and apoptosis was measured by PI staining and analyzed by flow cytometry (lower bar diagram). The bar diagrams show the media obtained from three independent experiments, and lines on the top of the bars represent the S.D. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test analysis was performed for statistical analysis. Symbols *, **, and *** indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

As the expression of BCL2 and c-FLIP depends on NF-κB activity, the ability of the main NF-κB subunit p65/RelA to bind DNA was analyzed by DNA affinity immunoblotting assay in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 cells in basal conditions, regarding control cells. As described previously, NF-κB binding capacity was higher in Jurkat-Tat101 than in Jurkat-Tat72 and, in turn, higher in Jurkat-Tat72 than in control cells (Fig. 8B) (23, 70). This was reflected in the enhancement of the expression of T cell activation markers such as CD69, which was 3.3-fold increased in Jurkat-Tat101 (p < 0.01) and 1.5-fold in Jurkat-Tat72 cells, regarding control cells (Fig. 8C). Treatment with FasL did not reduce significantly the expression of CD69 on the cell surface (p < 0.05). NF-κB transcriptional activity was also measured by transfecting p3κB-LUC vector (Fig. 8D). Jurkat-Tat101 cells showed 20-fold more NF-κB activity than control cells (p < 0.01) and 4-fold more than Jurkat-Tat72 (p < 0.01), in basal conditions. The treatment with FasL for 4 h reduced the NF-κB activity in all cell types, but the differences with control cells were maintained (p < 0.01).

To identify other regulators of apoptosis related to NF-κB, the expression of which could be modified by Tat, whole protein extracts from nonstimulated cells were hybridized in an antibody-based array that simultaneously detected 35 human apoptosis-related proteins, most of them related directly or indirectly to NF-κB activity. The expression of 11 proteins was deregulated in Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72, regarding the expression levels detected in control cells (Table 2). Both C-IAP2 and XIAP were enhanced in Jurkat-Tat101, whereas only XIAP was enhanced in Jurkat-Tat72 cells. Heat shock proteins 70 kDa (HSPA1A/1B) and 60 kDa (HSPD1) were also up-regulated in both Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72 cells. Surprisingly, Jurkat-Tat101 also showed great quantities of pro-apoptotic factors such as lymphotoxin α or Bax, which were not detected in Jurkat-Tat72. On the contrary, the expression of BCL2 interacting mediator of cell death (BIM/BCL2L11) was diminished 2-fold in Jurkat-Tat101. The analysis of the predicted interactions between these proteins by STRING 9.0 database showed a connection between all of them and that p65/RelA had a central position in the center of this complex network (Fig. 8E).

TABLE 2.

Proteins differentially expressed and detected by human apoptosis antibody array in protein extracts from Jurkat-Tat72 and Jurkat-Tat101 in comparison with Tet-Off cells

| Ratio |

Biological process | Subcellular localization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JJ Tat72 versus JJ Tet-Off | JJ Tat101 versus JJ Tet-Off | |||

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A (TNFRSF1A) | −10.00 | −3.33 | Pro-apoptosis | Cell membrane |

| NF-κB positive regulation | Secreted | |||

| BCL2-interacting mediator of cell death (BIM)/BCL2L11 | 1.00 | −2.70 | Pro-apoptosis | Mitochondrion |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (CDKN1A)/p21 | −1.75 | −2.63 | Cell cycle | Cytoplasm |

| Nucleus | ||||

| Heat shock 70-kDa protein 1A/1B (HSPA1A/B) | 2.03 | 1.50 | Stress response | Cytoplasm |

| Anti-apoptosis | Nucleus | |||

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6 (Fas) | 2.05 | 2.14 | Pro-apoptosis | Cell membrane |

| Secreted | ||||

| Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 4 (XIAP) | 2.14 | 2.25 | Anti-apoptosis | Cytoplasm |

| Nucleus | ||||

| Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 (IGFBP2) | −2.2 | 1.6 | Cell growth regulation | Secreted |

| Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 3 (C-IAP2) | 1.00 | 39.12 | Anti-apoptosis | Cytoplasm |

| Nucleus | ||||

| Lymphotoxin-α (LTA)/TNF-β (TNFB) | 1.00 | 60.35 | Pro-apoptosis | Cell membrane |

| Secreted | ||||

| Apoptosis regulator BAX/BCL2L4 | 1.00 | 101.21 | Pro-apoptosis | Cytoplasm |

| Mitochondrion | ||||

| 60-kDa heat shock protein (HSPD1) | 538.15 | 462.85 | Host-virus interaction | Mitochondrion |

Tat-mediated Activation of NF-κB through the ESKKKVE Motif Is Greatly Involved in the Induction of Resistance to Fas-mediated Apoptosis

The motif 86ESKKKVE92 located in Tat second exon has been described as critical for Tat-mediated NF-κB transactivation (70). Mutagenesis was performed in this motif to render a protein that should not be able to induce NF-κB activity. Both pTRE2hyg-Tat101 ESKKKVE (wild type) and pTRE2hyg-Tat101 ESRVNVV (mutated) were transiently co-transfected in Jurkat-Tet-Off cells along with p3κB-LUC vector. As shown Fig. 8F, Tat ESRVNVV induced a 1.9-fold lower activation of NF-κB activity than Tat ESKKKVE (p < 0.001). The treatment of these transfected cells with FasL for 4 h showed that Tat ESKKKVE was more efficient than Tat ESRVNVV in protecting them against FasL-induced apoptosis (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Activation of death signals is part of the antiviral immune response in the infected cell and represents a major threat to virus (71, 72). Many viruses have evolved mechanisms to inhibit apoptosis to the extent of the survival of infected cells, enhance the production of viral progeny, and permit the establishment of viral persistence. DNA viruses, such as adenovirus, Epstein-Barr, or African swine fever virus, encode viral anti-apoptotic proteins similar to cellular proteins, such as D-type cyclin, BCL2, and c-FLIP (73), whereas the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) maintains the cellular BCL2 levels through different mechanisms, including the activation of p38 MAPK (74). It is not well known whether the RNA viruses have similar mechanisms, but HIV-1-infected cells appear to have developed certain resistance to apoptosis to prolong the viral production (13, 14). The molecular mechanisms underlying this protection are not fully comprehended, but the intracellular expression of viral regulatory proteins such as Vpr or Tat during the first step of the viral replication may be involved. Interestingly, both proteins seem to overlap their function, suggesting that preventing apoptosis during the first steps of the HIV-1 replication is a crucial step for the viral cycle and its pathogenesis. Vpr exerts a dual role on regulating apoptosis during HIV-1 infection because, although extracellular or high intracellular levels of Vpr induce cellular death through the alteration of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (75, 76), an intracellular low concentration of Vpr seems to protect against FasL-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat cells (9). Similarly, we and others have previously described that the intracellular expression of HIV-1 Tat regulator protein appears to have an anti-apoptotic effect (23, 28, 77), but the mechanisms underlying this function of Tat have not been described yet. In this work, we show that the expression of the Tat second exon within the full-length Tat protein (Tat101) during HIV-1 replication enhances cellular survival in T lymphocytes during the first 72 h post-infection, and we describe the mechanisms involved. Furthermore, we demonstrated that PBLs, specifically, CD4+ T cells, and Jurkat cells expressing intracellular full-length Tat (Tat101) were more resistant to Fas-induced apoptosis than those expressing only the first exon (Tat72) or Tat-free control cells, and the molecular mechanisms involved in this process are described. Our data suggest that the protection against apoptosis mediated by full-length Tat occurred through two major mechanism as follows: first, a higher maintenance of the mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequent impairment in caspase-3 activation; and second, activation of NF-κB, which in turn induces the expression of survival proteins such as c-FLIP and BCL2. In these mechanisms, the presence of the second exon within full-length Tat appeared to be of paramount importance.

Resistance to apoptosis in HIV-1 persistently infected T cells is related to the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (78, 79). In Jurkat cells, the induction of Fas-mediated apoptosis requires an amplification step through the mitochondrial cell death pathway to activate caspase-3 (39, 45). This is achieved through the translocation of tBid to the mitochondrial membrane and subsequent release of cytochrome c (45, 47). The intracellular expression of Tat101 was able to maintain the mitochondrial outer membrane integrity by different mechanisms, delaying the release of cytochrome c and causing an inefficient activation of caspase-9 and -3. Tat72 was less competent than Tat101 to exert this protection. The quantification of caspase-3 activity by chemiluminescence did not correlate well with the cleavage of procaspase-3 to p17/p11 active forms in Jurkat-Tat72 cells. However, the lesser inhibitory effect of Tat72 on the activation of caspase-3 was confirmed through the analysis of PARP-1 cleavage, which was undoubtedly less effective in Jurkat-Tat101 than in Jurkat-Tat72.

The measure of ΔΨm showed that the mitochondrial depolarization was lower in Jurkat-Tat101 in response to FasL, likely due to the control exerted by c-FLIPS over the activity of caspase-8 and a lower cleavage of Bid but also due to the overexpression of other proteins such as BCL2 that may counteract this mechanism and stabilize the mitochondrial membrane (80, 81). BCL2 was described to be overexpressed by full-length Tat (55, 56), inducing protection against mitochondrially mediated apoptosis in Jurkat (82). BCL2 expression did not decrease in Jurkat-Tat101 even after a long treatment with FasL. As the cleavage of Bid and BCL2 levels was quite similar in Jurkat-Tat72 than in control cells, this would explain the higher mitochondrial depolarization observed in these cells, reinforcing the assumption that the ability of Tat to protect against apoptosis mostly resided in the second exon.

However, BCL2 was not the only protein responsible for delaying apoptosis as other proteins overexpressed by Tat101 and Tat72 were also able to stabilize the mitochondrial membrane potential such as several mitochondrial heat shock proteins (HSPD1, HSPE1, and HSPA1), nucleophosmin (NPM1), and BCL2-associated transcription factor 1 (BCLAF1). Overexpression of HSPs has been related to an increase in BCL2, mitochondrial membrane potential stabilization, impairment of cytochrome c release, caspase-3 inhibition, and suppression of PARP cleavage (83–85). HSPE1 was acetylated at Lys-99 in Jurkat-Tat101, which has been related to a higher gene expression regulation (86). BCLAF1 was also overexpressed by Tat101 and Tat72 and was heavily phosphorylated at Ser-177 and Ser-512 mainly in Jurkat-Tat101. Recent studies proved that BCLAF1 has a major role in T cell activation (87, 88). Besides, nucleolar NPM1 suppresses apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-mediated activation of DNase, favoring genomic stability and DNA repair (89), as well as by blocking p53 mitochondrial localization (90). NPM1 is known to interact with HIV-1 Rev (91) and Tat, being critical for Tat nuclear localization and Tat-mediated transcription (92). Although NPM1 was overexpressed in both Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72, it was deamidated at Asn-210 in Jurkat-Tat72; therefore, it was not fully functional in these cells. NPM1 also enhances the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and acts as a chaperone, binding only to activated and conformationally altered Bax (93). Bax was actually overexpressed in Jurkat-Tat101, as well as the BH3-domain only SOUL. SOUL has a similar function to Bax, inducing the mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and subsequent release of cytochrome c. The high expression of Bax in Jurkat-Tat101 could indicate a higher sensitivity to apoptosis. However, the pro-apoptotic function of Bax should be activated through the interaction with other factors as Bid or Bim, promoting a critical conformational change in Bax necessary for its death capacity (94, 95). In Jurkat-Tat101 cells, Bid was not efficiently cleaved to tBid, and the expression of Bim was reduced nearly 3-fold, indicating that the pro-apoptotic function of Bax was likely impaired by deficient activation. Moreover, Bim can be inhibited through its interaction with YWHAZ, a member of the 14-3-3 protein family that antagonizes the activity of pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bad, Bim, and Bax (96, 97). YWHAZ was enhanced in both Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72, although it was heavily deamidated in Jurkat-Tat72, likely rendering a not fully functional protein, unable to control the pro-apoptotic proteins. Other anti-apoptotic factors such as PHB contributed to the higher protection against apoptosis provided by Tat101 but not Tat72. PHB is a potent survival factor that inhibits the release of cytochrome c and caspase-3 activation (98, 99), and it was increased 70-fold in Jurkat-Tat101, which was 2-fold higher than in Jurkat-Tat72.

Overall, these results indicated that the higher stability of the mitochondrial membrane integrity in Jurkat-Tat101 was due to a group of stabilizing proteins acting together to prevent the release of cytochrome c. A direct consequence of this inhibition was the inefficient activation of caspase-3, which could hinder the activation of other cellular pathways as the cell cycle control. In fact, DNA replication factors as MCM2 and MCM3 were overexpressed in Jurkat-Tat101. MCM3 is the substrate for caspase-3 cleavage, and the truncated forms contribute to initiate apoptosis (100), inactivating the MCM complex and preventing DNA replication (101). The low caspase-3 activity detected in Jurkat-Tat101 would contribute to MCM3 stability and therefore to the maintenance of the MCM complex, avoiding apoptosis. Other factors related to cell cycle progression, cytokinesis, and cell proliferation were also overexpressed in Jurkat-Tat101, such as NUDC, NASP, and PCNA (102–105). The overexpression of somatic NASP has been related to changes in NF-κB activity (106), which is known to be enhanced by Tat (23, 70). NF-κB may in turn activate the expression of several potent anti-apoptotic factors as those belonging to IAP family. The expression of XIAP was enhanced in both Jurkat-Tat101 and Jurkat-Tat72, but C-IAP2 was only overexpressed in Jurkat-Tat101, nearly 40 times. XIAP is a potent inhibitor of initiator caspases, caspase-9 (107), as well as execution caspases, caspases-3 and -7 (108), preventing both CD95- and Bax-induced apoptosis (109, 110). This would explain the high quantities of procaspase-3, -8, and -9 that were detected in Jurkat-Tat101 even after treatment with FasL. C-IAP2 is a component of the tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) complex that inhibits cell death by direct repression of caspase activity (111), and it also targets for ubiquitin degradation several pro-apoptotic components of the TNF-α signaling pathway (112). Moreover, there should be a deregulation in the TNF signaling pathway because the expression of several components such as TNFRSF1A, Fas receptor, and TNF-β/lymphotoxin α showed an anomalous expression. Likely, the higher release of TNF cytokines by Jurkat-Tat cells was able to activate NF-κB via autocrine feedback, keeping a sustained activation of this transcription factor (113). As Tat72 lacks the motif 86ESKKKVE92, located in the second exon, which has been described as critical for NF-κB transactivation (70), the lower NF-κB basal activity detected in Jurkat-Tat72 regarding Jurkat-Tat101 should be related to this motif. Accordingly, Tat101 with mutated 86ESRVNVV92 motif was less efficient than wild-type Tat101 to activate NF-κB and protect Jurkat against FasL-mediated apoptosis.

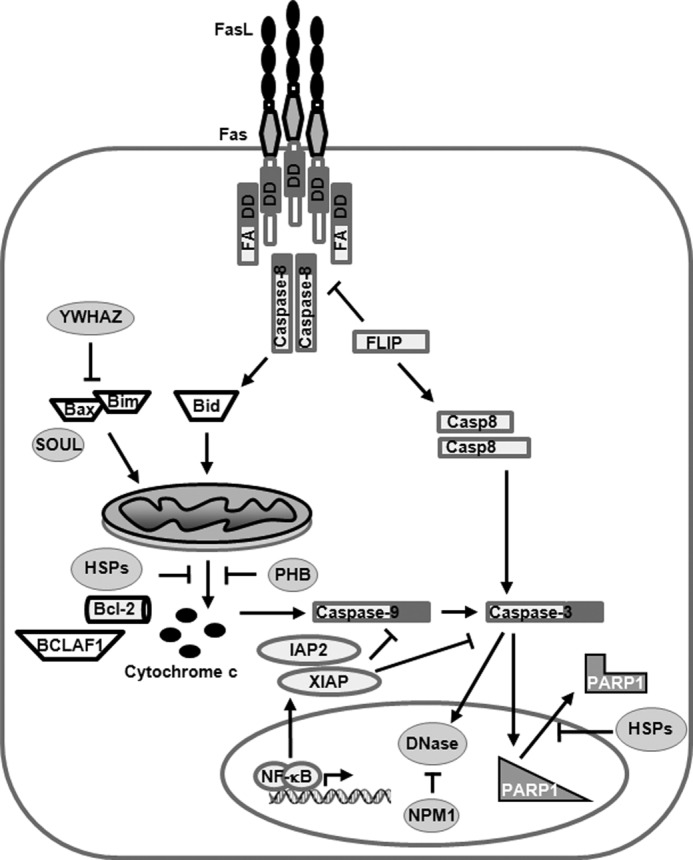

In summary, intracellular HIV-1 Tat deregulated the expression of several proteins related to apoptosis, rendering an anti-apoptotic general effect able to protect PBLs and Jurkat from FasL-induced apoptosis. This was achieved through the high stability of the mitochondrial membrane integrity because Tat101 increased the expression of several proteins, HSPs, NPM1, and PHB, committed to avoid mitochondrial depolarization, stabilize the cell cycle, and counteract pro-apoptotic factors such as Bid, Bim, or Bax. This effect was also achieved through the ability of Tat101 to activate NF-κB, an essential transactivating factor that promotes cell survival through different mechanisms, such as the up-regulation of C-IAP2, XIAP, BCL2, and c-FLIPS. As Tat72 lacks the essential motif ESKKKVE for activating NF-κB, this could be the most important mechanism through which Tat101 exerts its protective function. A scheme of the most important factors interfering with the apoptotic pathway in T lymphocytes, for which expression was modified by Tat, is depicted in Fig. 9.

FIGURE 9.

Model summarizing the steps in Fas apoptotic pathway that were thwarted by the intracellular expression of Tat. See Table 1, Table 2, and text for further explanation.

In conclusion, Tat101-mediated protection against apoptosis would allow a prolonged HIV-1 production and spread and might explain why apoptosis mostly occurs in bystander uninfected cells. This viral strategy would be mainly achieved through the second exon. A better understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for the resistance to apoptosis in HIV-infected T cells is essential to fully characterize the ability of HIV-1 to establish a long term infection.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the secretarial assistance of Olga Palao. We thank Centro de Transfusiones from Comunidad de Madrid, Spain, for providing the buffy coats.

This work was supported in part by Fundación para la Investigación y la Prevención del Sida en España Grant 360924/10, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Grant SAF2010-18388), Spanish Ministry of Health Grant EC11-285, AIDS Network Instituto del Salud Carlos III-Redes Temáticas de Investigación Cooperativa Grant RD06/0006, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Grant Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias PI080752, and the Network of Excellence EUROPRISE.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2 and Materials and Methods.

- DISC

- death-inducing signaling complex

- PBL

- peripheral blood lymphocyte

- PE

- phycoerythrin

- PI

- propidium iodide

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- RLU

- relative light unit

- tBid

- truncated Bid

- PHB

- prohibitin

- EYFP

- enhanced YFP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Piatak M., Jr., Saag M. S., Yang L. C., Clark S. J., Kappes J. C., Luk K. C., Hahn B. H., Shaw G. M., Lifson J. D. (1993) High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR. Science 259, 1749–1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lelièvre J. D., Mammano F., Arnoult D., Petit F., Grodet A., Estaquier J., Ameisen J. C. (2004) A novel mechanism for HIV1-mediated bystander CD4+ T-cell death: neighboring dying cells drive the capacity of HIV1 to kill noncycling primary CD4+ T cells. Cell Death Differ. 11, 1017–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gougeon M. L. (2005) To kill or be killed: how HIV exhausts the immune system. Cell Death Differ. 12, 845–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Varbanov M., Espert L., Biard-Piechaczyk M. (2006) Mechanisms of CD4 T-cell depletion triggered by HIV-1 viral proteins. AIDS Rev. 8, 221–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lum J. J., Cohen O. J., Nie Z., Weaver J. G., Gomez T. S., Yao X. J., Lynch D., Pilon A. A., Hawley N., Kim J. E., Chen Z., Montpetit M., Sanchez-Dardon J., Cohen E. A., Badley A. D. (2003) Vpr R77Q is associated with long-term nonprogressive HIV infection and impaired induction of apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1547–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacotot E., Ravagnan L., Loeffler M., Ferri K. F., Vieira H. L., Zamzami N., Costantini P., Druillennec S., Hoebeke J., Briand J. P., Irinopoulou T., Daugas E., Susin S. A., Cointe D., Xie Z. H., Reed J. C., Roques B. P., Kroemer G. (2000) The HIV-1 viral protein R induces apoptosis via a direct effect on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J. Exp. Med. 191, 33–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brenner C., Kroemer G. (2003) The mitochondriotoxic domain of Vpr determines HIV-1 virulence. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1455–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deniaud A., Brenner C., Kroemer G. (2004) Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by HIV-1 Vpr. Mitochondrion 4, 223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conti L., Rainaldi G., Matarrese P., Varano B., Rivabene R., Columba S., Sato A., Belardelli F., Malorni W., Gessani S. (1998) The HIV-1 Vpr protein acts as a negative regulator of apoptosis in a human lymphoblastoid T cell line: possible implications for the pathogenesis of AIDS. J. Exp. Med. 187, 403–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moon H. S., Yang J. S. (2006) Role of HIV Vpr as a regulator of apoptosis and an effector on bystander cells. Mol. Cells 21, 7–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finkel T. H., Tudor-Williams G., Banda N. K., Cotton M. F., Curiel T., Monks C., Baba T. W., Ruprecht R. M., Kupfer A. (1995) Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat. Med. 1, 129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nardelli B., Gonzalez C. J., Schechter M., Valentine F. T. (1995) CD4+ blood lymphocytes are rapidly killed in vitro by contact with autologous human immunodeficiency virus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7312–7316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aillet F., Masutani H., Elbim C., Raoul H., Chêne L., Nugeyre M. T., Paya C., Barré-Sinoussi F., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Israël N. (1998) Human immunodeficiency virus induces a dual regulation of Bcl-2, resulting in persistent infection of CD4+ T- or monocytic cell lines. J. Virol. 72, 9698–9705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang M., Li X., Pang X., Ding L., Wood O., Clouse K., Hewlett I., Dayton A. I. (2001) Identification of a potential HIV-induced source of bystander-mediated apoptosis in T cells: up-regulation of trail in primary human macrophages by HIV-1 tat. J. Biomed. Sci. 8, 290–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCloskey T. W., Ott M., Tribble E., Khan S. A., Teichberg S., Paul M. O., Pahwa S., Verdin E., Chirmule N. (1997) Dual role of HIV Tat in regulation of apoptosis in T cells. J. Immunol. 158, 1014–1019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bannwarth S., Gatignol A. (2005) HIV-1 TAR RNA: the target of molecular interactions between the virus and its host. Curr. HIV Res. 3, 61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berkhout B., Jeang K. T. (1989) Trans activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is sequence-specific for both the single-stranded bulge and loop of the trans-acting-responsive hairpin: a quantitative analysis. J. Virol. 63, 5501–5504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gatignol A., Jeang K. T. (2000) Tat as a transcriptional activator and a potential therapeutic target for HIV-1. Adv. Pharmacol. 48, 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pugliese A., Vidotto V., Beltramo T., Petrini S., Torre D. (2005) A review of HIV-1 Tat protein biological effects. Cell Biochem. Funct. 23, 223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carroll R., Martarano L., Derse D. (1991) Identification of lentivirus tat functional domains through generation of equine infectious anemia virus/human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat gene chimeras. J. Virol. 65, 3460–3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Westendorp M. O., Shatrov V. A., Schulze-Osthoff K., Frank R., Kraft M., Los M., Krammer P. H., Dröge W., Lehmann V. (1995) HIV-1 Tat potentiates TNF-induced NF-κB activation and cytotoxicity by altering the cellular redox state. EMBO J. 14, 546–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao H., Neuveut C., Benkirane M., Jeang K. T. (1998) Interaction of the second coding exon of Tat with human EF-1δ delineates a mechanism for HIV-1-mediated shut-off of host mRNA translation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 244, 384–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez-Huertas M. R., Callejas S., Abia D., Mateos E., Dopazo A., Alcami J., Coiras M. (2010) Modifications in host cell cytoskeleton structure and function mediated by intracellular HIV-1 Tat protein are greatly dependent on the second coding exon. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3287–3307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yedavalli V. S., Benkirane M., Jeang K. T. (2003) Tat and trans-activation-responsive (TAR) RNA-independent induction of HIV-1 long terminal repeat by human and murine cyclin T1 requires Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6404–6410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dandekar D. H., Ganesh K. N., Mitra D. (2004) HIV-1 Tat directly binds to NFκB enhancer sequence: role in viral and cellular gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1270–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang L., Morris G. F., Lockyer J. M., Lu M., Wang Z., Morris C. B. (1997) Distinct transcriptional pathways of TAR-dependent and TAR-independent human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transactivation by Tat. Virology 235, 48–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ott M., Emiliani S., Van Lint C., Herbein G., Lovett J., Chirmule N., McCloskey T., Pahwa S., Verdin E. (1997) Immune hyperactivation of HIV-1-infected T cells mediated by Tat and the CD28 pathway. Science 275, 1481–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coiras M., Camafeita E., Ureña T., López J. A., Caballero F., Fernández B., López-Huertas M. R., Pérez-Olmeda M., Alcamí J. (2006) Modifications in the human T cell proteome induced by intracellular HIV-1 Tat protein expression. Proteomics 6, S63–S73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pincus S. H., Messer K. G., Nara P. L., Blattner W. A., Colclough G., Reitz M. (1994) Temporal analysis of the antibody response to HIV envelope protein in HIV-infected laboratory workers. J. Clin. Invest. 93, 2505–2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith S. M., Pentlicky S., Klase Z., Singh M., Neuveut C., Lu C. Y., Reitz M. S., Jr., Yarchoan R., Marx P. A., Jeang K. T. (2003) An in vivo replication-important function in the second coding exon of Tat is constrained against mutation despite cytotoxic T lymphocyte selection. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44816–44825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]