Background: The bacterial condensin, MukB, and cellular decatenase, topoisomerase IV, interact.

Results: The MukB-topoisomerase IV interaction affects only intramolecular reactions catalyzed by topoisomerase IV.

Conclusion: The MukB-topoisomerase IV interaction is likely to be important for chromosome organization.

Significance: Interaction between the cellular condensin and decatenase may be necessary for efficient packaging of the chromosome, which is likely necessary for proper chromosome segregation.

Keywords: Chromosomes, DNA Binding Protein, DNA Structure, DNA Topoisomerase, DNA Topology, DNA Packaging, Condensin

Abstract

Proper chromosome organization is accomplished through binding of proteins such as condensins that shape the DNA and by modulation of chromosome topology by the action of topoisomerases. We found that the interaction between MukB, the bacterial condensin, and ParC, a subunit of topoisomerase IV, enhanced relaxation of negatively supercoiled DNA and knotting by topoisomerase IV, which are intramolecular DNA rearrangements but not decatenation of multiply linked DNA dimers, which is an intermolecular DNA rearrangement required for proper segregation of daughter chromosomes. MukB DNA binding and a specific chiral arrangement of the DNA was required for topoisomerase IV stimulation because relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA was unaffected. This effect could be attributed to a more effective topological reconfiguration of the negatively supercoiled compared with positively supercoiled DNA by MukB. These data suggest that the MukB-ParC interaction may play a role in chromosome organization rather than in separation of daughter chromosomes.

Introduction

Disruption of proper chromosome organization can lead to genomic instability. One major chromosomal organizing principle is topological and is mediated by DNA topoisomerases that can relieve topological strain induced by DNA replication and transcription and remove unwanted or errant DNA linkages. Type II topoisomerases, which operate by passing one segment of a DNA duplex through a double-stranded break and then resealing that break, are particularly important for maintaining chromosome organization (1). Escherichia coli possesses two type II enzymes: DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV (Topo IV)3. By introducing negative supercoils to DNA, gyrase removes positive supercoils ahead of the replication fork and condenses nascent DNA by maintaining negative supercoiling (1). Topo IV is a potent decatenase that unlinks the daughter chromosomes at the end of replication (2, 3) and can relax both positively (+) and negatively (−) supercoiled (sc) DNA, although it prefers the former as a substrate (4–6). It is a heterodimer of two subunits, ParC, the catalytic subunit, and ParE, the ATPase subunit (7, 8). Compromising Topo IV function in the cell leads to a partition (par) phenotype characterized by one or two large unsegregated masses of DNA and extreme cell filamentation (7, 9).

The condensin complex is a crucial player in chromosome organization in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (10). The E. coli condensin consists of three subunits, MukB, MukE, and MukF. Genes encoding those proteins are transcribed from an operon and disrupting any of the genes results in a temperature-sensitive phenotype characterized by cell filamentation and anucleate cell formation (11, 12). MukB belongs to the structural maintenance of chromosomes protein family and forms a homodimer that consists of head, arm, and hinge domains (10). The accessory subunits MukE and MukF also form a complex and bind to MukB on its head domain (13). Binding of condensins to circular DNA can introduce supercoils, the chirality of which differs among species (14–16) and knots with (+) writhes (15–17) in the presence of type II topoisomerases. Recent observations suggest that condensins can form a protein ring that binds DNA topologically, similar to cohesins in eukaryotes (10, 18).

We and others (19, 20) have reported previously that MukB and ParC physically and functionally interact, however the specific biochemical process in which this interaction played a role was not evident. In this work, we demonstrate that the interaction enhances intramolecular DNA reactions catalyzed by Topo IV, but not intermolecular ones; suggesting that the functional interaction between MukB and ParC could play a role in chromosome organization rather than chromosome separation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids, Strains, and Proteins

Expression plasmids for MukB variants were based on pET11a-mukB (19). Plasmids pET11a-mukBR187ER189E (mukBdna) and pET11a-mukBD697KD745KE753K (mukBtriple) were generated by site-specific mutagenesis using a kit from Agilent Technologies. pCG09 plasmid DNA used in the knotting assay and modulation of DNA topology assay was created by inserting a lacZ-lacY PCR fragment copied from MG1655 genomic DNA into the NheI and HindIII sites of pBRcos (21). pSB5 plasmid DNA used in the preparation of the multiply linked DNA dimers is identical to pBROTB-I-535 (22) except that the 1007-bp region flanked by the two ter sites is inverted.

Tagged and untagged Topo IV and DNA gyrase were purified as described previously (8, 23). All of the MukB variants were purified as described previously (19). The purification of the MukEF complex will be described elsewhere.

In Vitro Pulldown Assay

The in vitro pulldown assay with HA-ParC and purified MukB proteins was as described previously (19).

ATPase Assays

ATPase reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 50 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 20 mm KCl, 2 mm Mg(OAc)2, 100 μg/ml BSA, 10 mm DTT, 2 mm ATP, 6 nm [γ-32P]ATP), 400 nm MukB (wild-type and mutant variants), and 400 nm MukEF complex, as indicated were incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of EDTA to 80 mm followed by incubation at 37 °C for 5 min. An aliquot (1 μl) of the sample was spotted on to polyethyleneimine-cellulose plates, and free phosphate was separated from nuceotide by thin layer chromatography using 0.5 m LiCl in 1 m HCOOH as the solvent. The plates were dried and imaged using a Fuji phosphoimaging device. The images were analyzed with ImageGauge software (Fuji Film).

Superhelical DNA Relaxation Assay

Topo IV-catalyzed superhelical DNA relaxation assays containing 4–10 nm Topo IV were as described previously using pUCO DNA (24) as the substrate. Positively supercoiled DNA was prepared by treating (−) sc pUCO DNA with reverse gyrase (a gift of T. S. Hsieh, Duke University). Reaction mixtures (10 × 100 μl) containing 2 μg of (−) sc pUCO DNA, 42 nm reverse gyrase, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0 at 4 °C), 10 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm ATP were incubated at 95 °C for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of NaCl and EDTA to 300 and 20 mm, respectively, and cooled on ice for 5 min. SDS and Proteinase K were then added to 0.4% and 100 μg/ml, respectively, and the incubation continued at 37 °C for 20 min. The DNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Based on counting of topoisomer bands present in partially relaxed preparations on agarose gels in the presence and absence of netropsin, we estimate that the minimal superhelical density of the (+) sc DNA is +0.04. Because all of the positive superhelical topoisomers cannot be resolved by gel electrophoresis, the actual superhelical density is probably greater than this value. This estimate is consistent with that determined by Crisona et al. (6).

Assay for Modulation of DNA Topology

Reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 50 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 20 mm KCl, 100 μg/ml BSA, 10 mm DTT, 0.5 mm Mg(OAc)2, the indicated concentrations of MukB, 100 ng of either (−) sc or (+) sc pCG09 plasmid DNA, as indicated, and 5 ng of vaccinia virus DNA topoisomerase I (the gift of Stewart Shuman, this institution), as indicated, were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. EDTA, proteinase K, and SDS were then added to 20 mm, 100 μg/ml, and 0.5%, respectively, and the incubation was continued for an additional 20 min. Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis at 3 V/cm for 17 h through vertical 0.9% agarose gels either in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml chloroquine in the gel and electrophoresis buffer using 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.8 at 23 °C), 40 mm NaOAc, 1 mm EDTA (TAE) as the electrophoresis buffer. Gels were stained with SYBR Gold (Invitrogen) and scanned using a Fuji FLA-5000 fluorimeter, and the images were analyzed using Fuji ImageGauge software. (+) sc pCG09 DNA was prepared as described above for pUCO DNA.

Decatenation of Multiply Linked Dimers

Multiply linked, form II:form II DNA dimers (MLD) were purified from oriC replication reactions using pSB5 plasmid DNA as the template as described (25). Decatenation reaction mixtures (7.5 μl) containing 50 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 20 mm KCl, 100 μg/ml BSA, 10 mm DTT, 2 mm ATP, and 0.5 nm MLD were first incubated with the indicated concentrations of MukB at 37 °C for 10 min, Topo IV was then added to 30 pm, and the incubation continued at 37 °C for 5 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of EDTA and NaCl to 20 and 300 mm, respectively, and the incubation continued at 37 °C for 3 min. SDS and Proteinase K were then added to 0.5% and 100 μg/ml, respectively, and the incubation was continued at 37 °C for 15 min. DNA products were analyzed by electrophoresis through vertical 0.8% agarose gels at 2.2 V/cm for 16 h using TAE as the electrophoresis buffer. Gels were dried, exposed to phosphoimaging screens for quantification (using a Fujifilm FLA-7000 phosphorimaging device), and autoradiographed. Scans were analyzed with Fujifilm Image Gauge software.

DNA Knotting Assay

Nicked DNA was prepared in a reaction mixture (400 μl) containing 1× New England Biolabs buffer 2, 40 μg of pCG09 DNA, and 360 units of Nb·BbvCI, as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). DNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation after extraction with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1).

DNA knotting reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 100 ng of nicked pCG09 DNA, 50 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 20 mm KCl, 100 μg/ml BSA, 10 mm DTT, 2 mm Mg(OAc)2, 2 mm ATP, 600 nm MukB or MukB variants, and either 6 nm Topo IV (either wild type or reconstituted with ParE and ParC R705E/R729A) or 2.5 units of human topoisomerase II (Topogen), were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of EDTA and NaCl to 20 and 150 mm, respectively, and the incubation continued at 37 °C for 5 min. SDS and proteinase K were then added to 0.5% and 100 μg/ml, respectively, and the incubation continued at 37 °C for 15 min. Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis at 3 V/cm for 21 h through vertical 0.8% agarose gels using TAE as the electrophoresis buffer, which was recirculated during the run. Gels were stained with SYBR Gold (Invitrogen), scanned using a Fuji FLA-5000 fluorimeter, and the images analyzed using Fuji ImageGauge software. The extent of knotting was calculated by determining the fraction of total DNA in the lane that appeared as knots.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing 50 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 40 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 50 ng pUCO DNA, 7% glycerol, and the indicated concentrations of MukB were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The samples were immediately loaded onto a vertical 1% agarose gel and electrophoresed at 2.5 V/cm for 14 h using TAE as the electrophoresis buffer. The gel was stained with SYBR Gold, imaged using a Kodak Image Station 4000R, and analyzed as described above.

RESULTS

Characterization of a ParC Noninteracting MukB Mutant Protein

The C-terminal domain of ParC interacts with the hinge domain of MukB. Although loss-of-MukB interaction variants of ParC have been reported, we had not constructed reciprocal variants for MukB (19, 20). We therefore screened site-specific amino acid substitutions on the MukB hinge domain in vitro and identified three residues whose mutation resulted in a loss of interaction with ParC: Asp697, Asp745, and Glu754. The side chains of these three residues are solvent-exposed in the crystal structure (26) and create a potential surface for the interaction. Indeed, a preliminary co-crystal structure of the ParC C-terminal domain and the MukB hinge domain indicates that the previously identified Arg705 and Arg729 residues on ParC, and the three noted above on MukB are all involved in the interaction.4 The purified MukB D697K/D745K/E753K (MukBtriple) mutant protein failed to interact with wild-type HA-ParC (Fig. 1A). Neither the DNA-binding activity of MukBtriple, as measured in an EMSA (Fig. 1B) nor its ATPase activity in the presence of MukE and MukF (Table 1) was affected by the triple mutation, so we utilized this variant as a separation-of-function mutant.

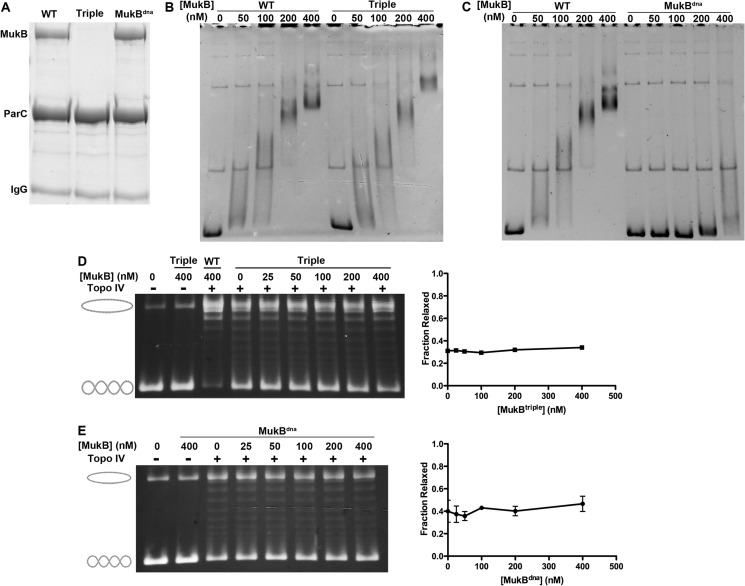

FIGURE 1.

The DNA-binding and ParC-interacting activities of MukB are required to stimulate (−) sc DNA relaxation by Topo IV. A, the DNA binding-deficient variant MukBdna but not the non-ParC-interacting variant MukBtriple (Triple), binds HA-ParC in a pulldown assay. HA-ParC was bound to anti-HA-agarose beads and used as bait to capture the MukB variants as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, MukBtriple has normal DNA binding activity. The DNA-binding activity of wild-type (WT) and MukBtriple (Triple) were compared in an EMSA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C, MukBdna is deficient in DNA-binding activity. The DNA-binding activity of wild-type (WT) and MukBdna (dna) were compared in an EMSA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, MukBtriple (Triple) does not affect Topo IV-catalyzed relaxation of (−) sc DNA. Relaxation assays were as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Quantification is the average of two experiments. E, MukBdna does not affect Topo IV-catalyzed relaxation of (−) sc DNA. Relaxation assays were as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Quantification is the mean and S.E. of three experiments.

TABLE 1.

ATPase activity of MukB variant proteins

| Sample | ATP hydrolyzed/min/MukB dimer |

|---|---|

| No protein | <0.1 |

| MukE2F | 0.9 |

| Wild-type MukB | 5.7 |

| MukB R187E/R189E | 3.9 |

| MukB D697K | 11.7 |

| MukB D697K/D745K/E753K | 16.4 |

| Wild-type MukB + MukE2F | 18.0 |

| MukB R187E/R189E + MukE2F | 46.6 |

| MukB D697K + MukE2F | 24.3 |

| MukB D697K/D745K/E753K + MukE2F | 20.8 |

MukB Binding to DNA and Interaction with ParC Are Required to Stimulate Relaxation of (−) sc DNA by Topo IV

MukB stimulates (−) sc DNA relaxation by Topo IV and disrupting the interaction with MukB by reconstituting Topo IV with mutant ParC R705E/R729A ablates this stimulation (19, 20). As expected, therefore, MukBtriple did not stimulate (−) sc relaxation by wild-type Topo IV (Fig. 1D), strongly indicating that the physical interaction between MukB and ParC is required for the functional effect.

To test whether the DNA binding activity of MukB was required for the observed stimulation we purified MukB R187E/R189E (MukBdna). These two amino acid substitutions are the equivalent of the R216E and R218E mutations made in Haemophilus ducreyi MukB that elicited DNA binding deficiency (13). These two mutations sit on the head domain of the MukB dimer. As expected, MukBdna failed to bind plasmid DNA (Fig. 1C) but retained the ability to interact with HA-ParC (Fig. 1A), indicating that these mutations on the head domain do not affect the interaction surface for ParC binding on the hinge domain.

MukBdna was unable to stimulate (−) sc relaxation by Topo IV (Fig. 1E), indicating that the DNA binding activity of MukB is required for the stimulation. Because MukBdna presumably retains a functional hinge and coiled-coil domain, this result argues against the idea proposed by Li et al. (20) that the MukB hinge domain alone is sufficient to stimulate the activity of Topo IV. Although it is possible that a MukB hinge domain attached to an inactive head domain may not be capable of stimulation, our observations argue that both the head and the hinge domains of MukB are necessary for a functional interaction between the two proteins.

MukB Does Not Stimulate Topo IV-catalyzed Relaxation of (+) sc DNA

Topo IV is more efficient at removing positive supercoils than negative ones, so we tested whether MukB had any effect on (+) sc relaxation by Topo IV. (+) sc DNA was first incubated with varying concentrations of MukB, and then Topo IV was added to relax the DNA. As expected, Topo IV was more active with (+) sc than (−) sc DNA; however, MukB failed to stimulate this activity (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting that there is a preference for a specific DNA chirality in the reaction.

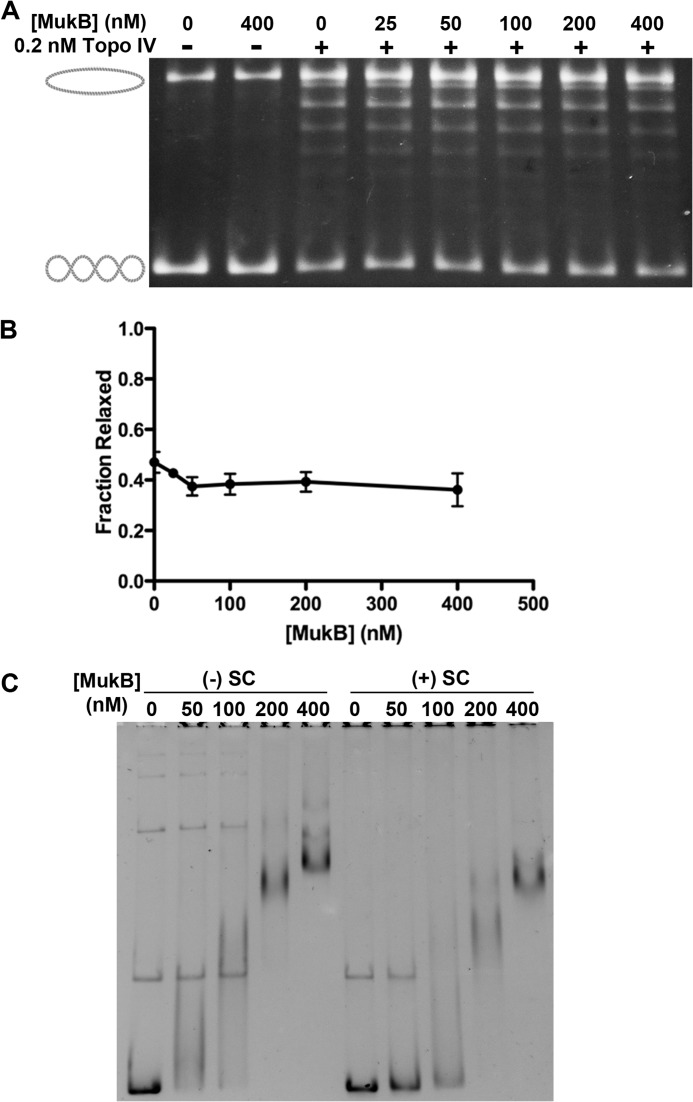

FIGURE 2.

Stimulation of Topo IV activity by MukB is dependent on DNA substrate topology. A, MukB does not affect Topo IV-catalyzed relaxation of (+) sc DNA. Relaxation assays were as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, a quantification of three different assays such as the one shown in A is shown. C, MukB binds to both (+) and (−) sc DNA. EMSAs were as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

The lack of stimulation did not arise from a deficiency in MukB binding to (+) sc compared with (−) sc DNA. MukB bound both DNA substrates in an EMSA (Fig. 2C). Although MukB appears to bind (−) sc DNA more efficiently than (+) sc DNA, the difference is small and is unlikely to account for the observed effect. Single molecule measurements indicate that the rate of relaxation of (+) sc by Topo IV was 20-fold greater than that of (−) sc (6). MukB might boost Topo IV activity on (−) sc DNA by reconfiguring the substrate by the introduction of (+) writhes. Adding more (+) writhes to (+) sc DNA might fail to increase the rate of an already maximized Topo IV.

To assess this possibility, we investigated the ability of MukB to reconfigure either (−) or (+) sc DNA by binding MukB to the DNA at various concentrations and then treating the bound protein-DNA complex with topoisomerase I from vaccinia virus. This topoisomerase relaxes both (−) and (+) sc DNA with nearly equal efficiency. If the binding of a protein to the DNA stabilizes (−) supercoils, compensatory (+) supercoils form elsewhere in the DNA that will be relaxed by the vaccinia topoiosmerase, leaving a residuum of (−) supercoils once all protein is removed from the DNA and vice versa. Thus, residual supercoils in this type of experiment report on supercoils that were stabilized by the protein bound to the DNA. Under these conditions, MukB binding to (−) sc DNA resulted in a residuum of (−) sc, compared with the result when there was no protein bound to the DNA (Fig. 3). This effect was much less prominent when the substrate was (+) sc DNA. At low concentrations of MukB, stabilization of (−) sc was detected because a slight (−) sc residuum could be observed. At the highest concentration of MukB tested, it appeared as if (+) sc were actually stabilized on the (+) sc DNA. However, this effect arises because of a slight preference for relaxing (+) sc by the vaccinia topoisomerase. Binding of MukB to the (+) sc DNA at this high concentration induced so many compensatory (+) sc that the topoisomerase was not able to relax them all during the incubation. Doubling the concentration of vaccinia topoiosmerase eliminated this population (data not shown).

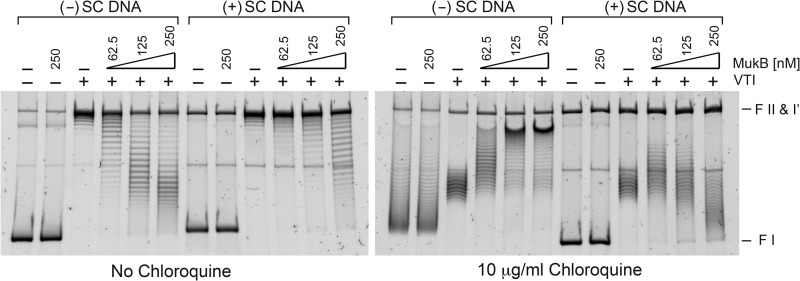

FIGURE 3.

MukB reconfigures the topology of (−) sc DNA more effectively than that of (+) sc DNA. The indicated concentrations of MukB were bound to either (−) or (+) sc DNA and residual sc were revealed by treating the protein-DNA complexes with vaccinia virus topoisomerase I in excess of the amount required to relax completely the DNA substrate by itself. The assays are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis through gels in either the presence (right panel) or absence (left panel) of 10 μg/ml chloroquine. Chloroquine unwinds duplex DNA. Thus, during electrophoresis through gels containing low concentrations of chloroquine, the mobility of topoisomers of (−) sc DNA will decrease and that of (+) sc DNA will increase compared to their mobility through gels that do not contain chloroquine. This experiment was repeated six times, and the results were identical. A representative gel is shown. VT1, vaccinia topoisomerase I. FI, form I DNA; FII, form II DNA; form I', form I' DNA.

It was clear, however, that topological reconfiguration of the DNA by MukB was far more efficient on the (−) sc DNA substrate than the (+) sc DNA substrate and that this reconfiguration consisted of the stabilization of (−) sc. This observation is consistent with the finding of Petrushenko et al. (15) that MukB stabilizes (−) sc in relaxed DNA. We conclude that the enhanced rate of Topo IV-catalyzed relaxation observed in the presence of MukB on (−) sc DNA substrates is a result of the induction of a preferred binding site for Topo IV (the compensatory (+) sc) mediated by the MukB-ParC interaction. Interestingly, it must be the case that despite the fact that this effect induces additional (−) sc in the DNA substrate, the gain in binding of Topo IV to the substrate increases the overall rate of relaxation, whereas with a (+) sc substrate, this rate is already maximized.

MukB Does Not Affect the Decatenation Activity of Topo IV

We demonstrated previously that MukB had a minimal effect on the decatenation activity of Topo IV using kinetoplast DNA as the substrate (19), and we could not confidently conclude that the extent of stimulation was significant. Although kinetoplast DNA is a convenient substrate to assess decatenation activity of a type II topoisomerase, it is not an optimal substrate for testing the activity of Topo IV because the actual substrate for Topo IV in vivo, catenated daughter chromosomes, is quite different in structure from kinetoplast DNA. To model the endogenous substrate, we purified MLDs from a θ-type plasmid DNA replication reaction in vitro (27). The topology of the multiple linkages between the two daughter DNA circles is exactly the same as those in catenated chromosomes, whereas with kinetoplast DNA the minicircles are linked only once to the maxicircle.

MLDs were first incubated with varying concentrations of MukB and Topo IV was then added to unlink the DNA circles. Topo IV alone efficiently removed linkages and shifted the distribution of linkages in the MLDs toward lower linkage numbers. The presence of MukB, however, had no effect on the reaction: no change in the linkage number distribution of MLDs was observed (Fig. 4A).

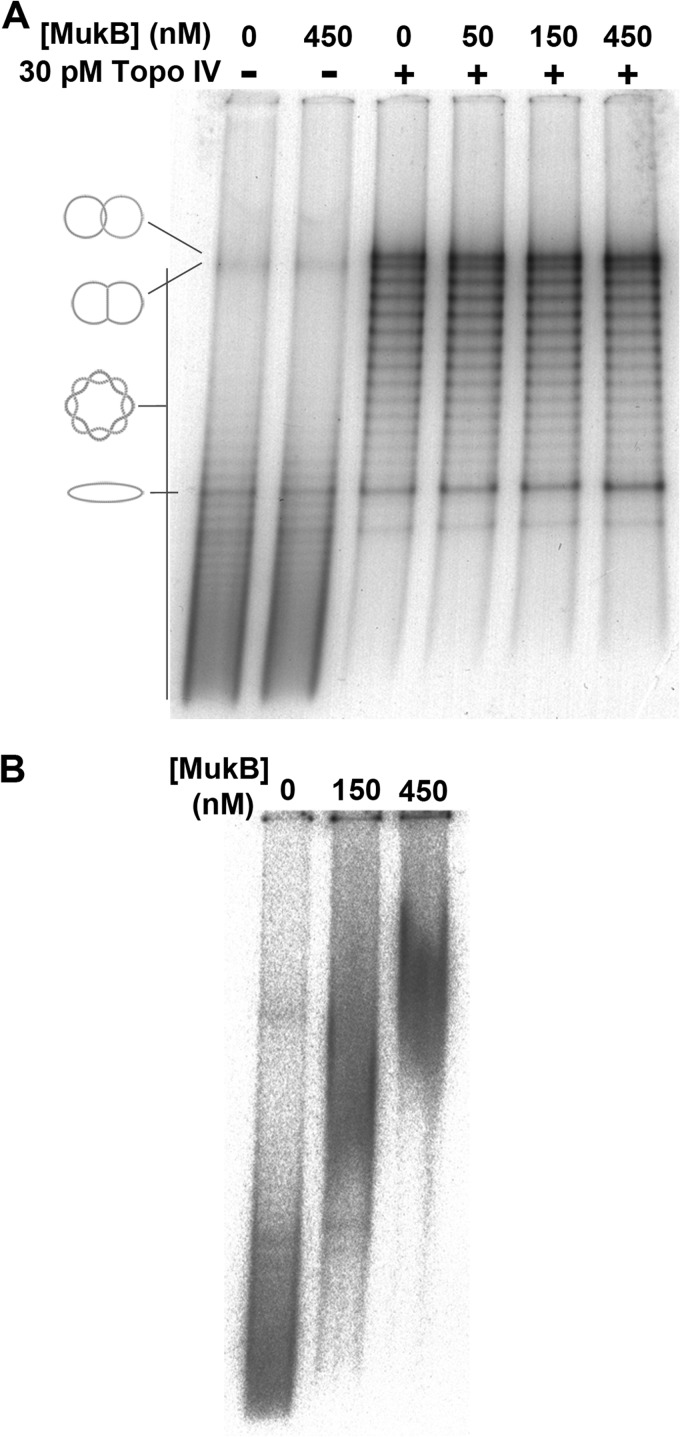

FIGURE 4.

MukB does not affect Topo IV-catalyzed decatenation of MLDs. A, MLDs migrate as a ladder of bands; DNA species with higher intermolecular linking numbers migrate faster. Singly linked dimers and unlinked monomers have distinct electrophoretic mobility, as indicated in the diagram on the left. Late replication intermediates migrate slightly faster than the singly linked dimers. Decatenation assays were as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, MukB can bind to MLDs in an EMSA.

The absence of a MukB effect on the reaction was not because of an inability of the protein to bind the MLDs. An EMSA (Fig. 4B) showed that MukB bound these DNA molecules quite well at the concentrations used in the decatenation reaction. We conclude that the MukB-ParC interaction is irrelevant in intermolecular DNA rearrangements catalyzed by Topo IV.

The MukB-ParC Interaction Enhances the Efficiency of DNA Knotting

The elimination of decatenation as the biochemical target of the MukB-ParC interaction left intramolecular DNA rearrangements catalyzed by Topo IV as the obvious target. However, it was unlikely that (−) sc relaxation was the reaction targeted because an increased rate of removal of (−) sc would act to decondense chromosomes. Condensins, however, are able to knot circular DNA, which is a chromosome-condensing reaction, in the presence of a type II topoisomerases (15–17). We therefore examined whether Topo IV and MukB supported a knotting reaction.

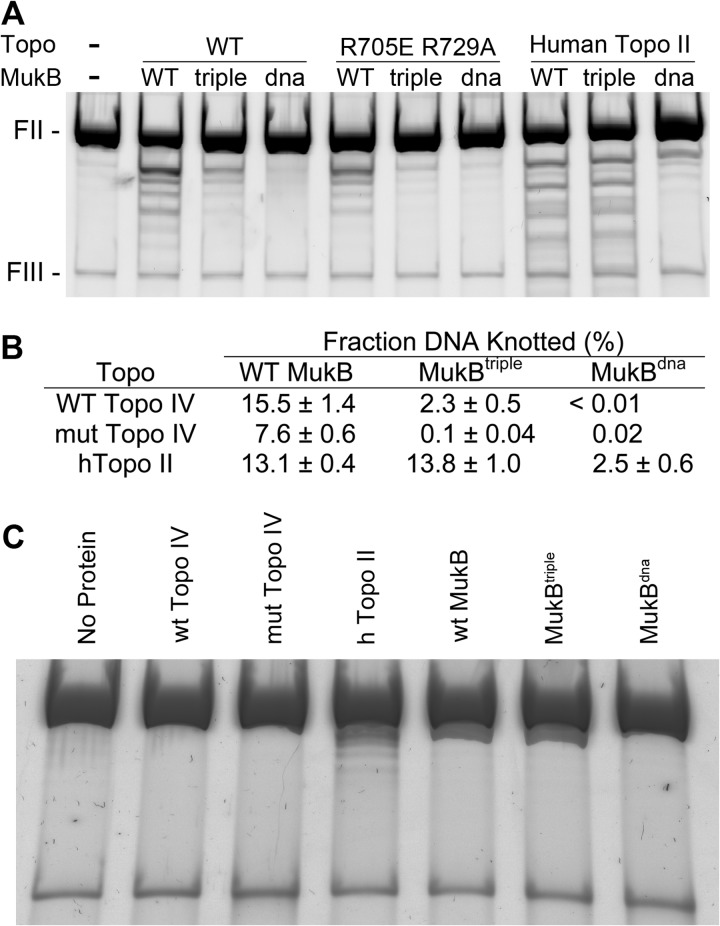

Nicked circular (form II) DNA was mixed with MukB and Topo IV, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow knots to form. Different combinations of MukB variants (wild-type, MukBtriple, and MukBdna) and topoisomerases (wild-type Topo IV, Topo IV reconstituted with ParC R705E/R729A, and human topoisomerase II) were tested (Fig. 5). The combination of wild-type MukB and wild-type Topo IV yielded the most knots. Replacing the wild-type Topo IV with the non-interacting variant halved the extent of knotting, whereas replacing the wild-type MukB with MukBtriple reduced knotting by 85%. Combining both non-interacting mutants effectively eliminated knotting (Fig. 5, A and B). These results argue that the interaction facilitates knotting and suggest that MukBtriple may be more efficient at completely disrupting the interaction than ParC R705E/R729A. No significant knot formation was observed with MukBdna, indicating that the DNA binding activity of MukB is required for knotting. Human topoisomerase II, which presumably does not interact with MukB, elaborated the same knotting efficiency with either wild-type or MukBtriple, suggesting that the enhancement of knotting efficiency is specific to the MukB-ParC (Topo IV) pair. None of the proteins used in these experiments exhibited significant knotting activity on their own (Fig. 5C). (The human Topo II, which shows slight knotting activity, was a commercial preparation and thus may be contaminated with other DNA-binding proteins.) The observed lack of stimulation by MukB of Topo IV-catalyzed decatenation, under conditions where MukB was clearly able to bind to the DNA substrate and interact with Topo IV, coupled with the requirement for the MukB-Topo IV interaction to stimulate Topo IV-catalyzed knotting of DNA argues strongly that the MukB-Topo IV interaction facilitates reactions involved in chromosome organization rather than chromosome decatenation.

FIGURE 5.

The MukB-ParC interaction enhances MukB-dependent, Topo IV-catalyzed DNA knotting. A, DNA knotting was examined in the presence of MukB, MukBtriple, and MukBdna using wild-type Topo IV, ParC R705E/R729A Topo IV, and human Topo II as described under “Experimental Procedures.” FII, form II DNA; FIII, form III DNA. B, knot formation was quantified for three independent reactions. The mean and S.E. are given. C, controls for base-line knotting activity. The indicated proteins were incubated alone under the conditions of the knotting assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” mut, mutant; h, human.

DISCUSSION

Activity Enhancement of Topo IV by MukB Is Dependent on the Physical Interaction and DNA Binding Activity of MukB

As expected from our previous results (19), a MukB variant protein deficient in the interaction with ParC failed to stimulate (−) sc relaxation by Topo IV. Furthermore, MukB DNA-binding activity was also required to stimulate Topo IV activity. These observations indicate that macromolecular engagement of both the head and the hinge domains of a MukB dimer are required to stimulate Topo IV. It is possible that MukB interacts with one segment of DNA via the head domain while interacting with Topo IV, which itself is engaged with another segment of DNA. It has been reported previously that the hinge domain of MukB alone was sufficient for the stimulation (20); however, our results indicate that a full-length dimer is required. It is also possible that the conformation of purified hinge domain is different than the one in a full-length dimer, and its conformation somehow stimulated Topo IV activity directly. However, it is improbable that the hinge domain alone reconfigures DNA in such a way that Topo IV can act on it more efficiently because the hinge domain does not bind to DNA at the concentrations of MukB tested here (26). Our results strongly suggests that Topo IV activity is not directly regulated by physical interaction with MukB via the hinge domain but rather that DNA reconfiguration by MukB is also important for the stimulatory effect. This thesis is also consistent with our observation that the DNA binding activity of MukB was essential for the formation of knots.

The Effect of MukB Is Dependent on the Topology of the DNA Substrate

Our observations suggest that MukB prefers DNA substrates with a certain chirality for its stimulatory action. Relaxation of (−) sc DNA was stimulated but not that of (+) sc DNA nor unlinking of MLDs. Interestingly, although not intuitive, (+) sc DNA and the monomer rings of MLDs each carry (+) writhes, with the latter arising from the path of the right-handed catenane linkages (28). Thus, it is possible that MukB discriminates against DNA with (+) writhes in the context of the MukB-ParC interaction. We observed a minimal difference in DNA binding activity of MukB on (+) and (−) sc DNA, so it is unlikely that a strong discrimination takes place when MukB binds to DNA. However, reconfiguration of DNA by MukB stabilization of (−) sc was more effective on (−) sc DNA compared with (+) sc DNA, arguing that MukB is only able to optimize certain substrates for Topo IV by the introduction of local compensatory (+) writhes to the DNA. Consistent with this argument is the finding that >95% of the trefoil knots formed in the presence of MukB and bacteriophage T2 topo II were of the (+) form (15).

We therefore consider it most likely that MukB reconfigures DNA first and the MukB-ParC interaction enhances subsequent strand passage catalyzed by Topo IV in some manner. However, regardless of the mechanism, the inability of MukB to affect removal of MLD-like catenanes makes it unlikely that MukB is involved directly in the topological separation of the daughter chromosomes.

A Chromosome Organizing Role for the MukB-ParC Interaction?

Interestingly, the eukaryotic condensin and type II topoisomerase also interact (29). These proteins are known to be constituents of the scaffold of condensed metaphase chromosomes, display a barber pole-like localization pattern (30), and are essential for proper chromosome organization and segregation (29–31). There is some debate in the literature over the precise roles of these proteins in chromosome condensation from prophase to metaphase (32, 33); however, it is evident that their functions are essential to create suitable chromosome structures for the eventual separation of the sister chromatids in anaphase. Considering the evolutionary conservation of important biological functions and the coexistence of condensin complexes and type II topoisomerases, especially Topo IV in prokaryotes, it is conceivable that the same mechanism exists in bacteria. Clearly, the bacterial condensin complex is required for proper organization of the chromosome. And although Topo IV plays a major role in the cell as the decatenating enzyme, additional functions as either a structural component of the chromosome or nucleoid are possible. These additional functions might even be exclusive to ParC.

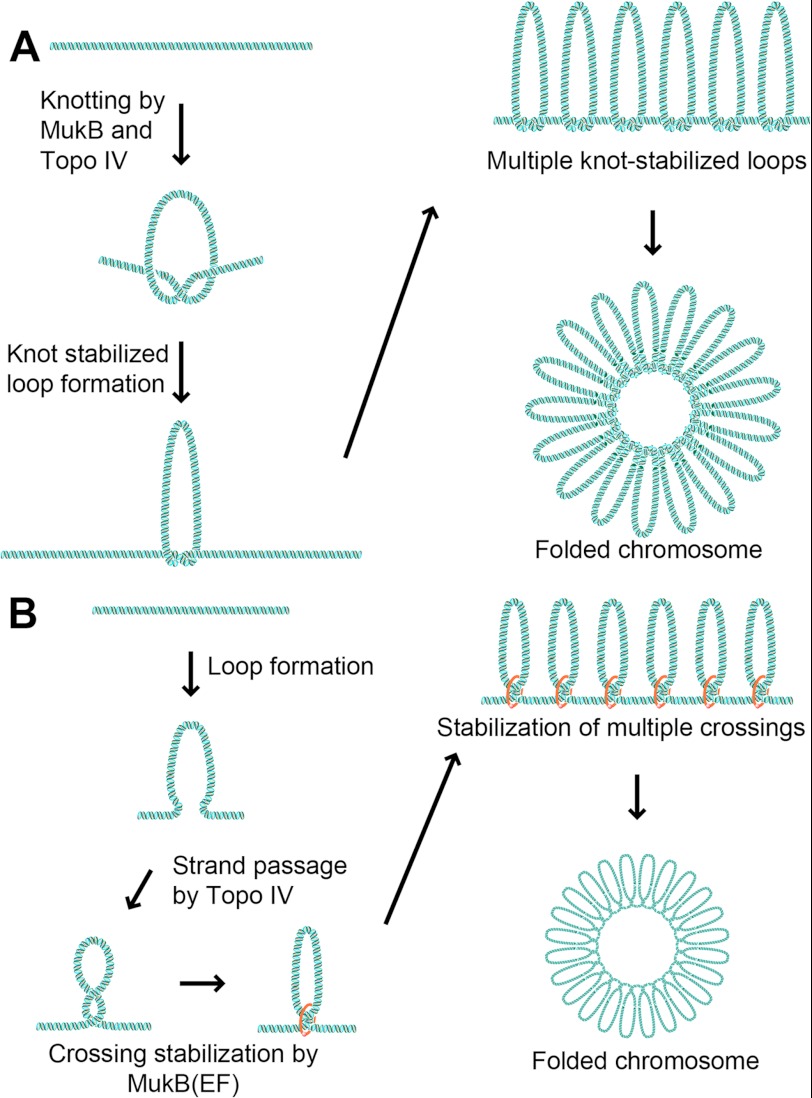

What is the biochemical reaction that is impacted in vivo by the MukB-ParC interaction? Our biochemical data indicates that MukB facilitates intramolecular DNA rearrangements catalyzed by Topo IV in a DNA topology-dependent manner. Because Topo IV is incapable of supercoiling DNA and relaxation of supercoiling would decondense the chromosome, it seems likely that this MukB-stimulated, Topo IV-catalyzed reaction links distal segments of the chromosome in some manner. It is possible that this reaction could be knotting of the DNA. Little is known as to whether the chromosome is knotted, but knots would act to condense the DNA. In a knot-stabilized loop model of chromosome organization, MukB and Topo IV could act on a protein-free segment of DNA to introduce a knot (Fig. 6A). Such a reaction creates a DNA loop whose base is stabilized by the knot. Continuous action of the two enzymes could create multiple knot-stabilized loops, which would eventually create a structure similar to that observed in the electron microscope (34).

FIGURE 6.

Models for chromosome organization by MukB and Topo IV. A, knot stabilization. B, loop stabilization. The models are described in the text.

Another possibility is that Topo IV action in concert with MukB DNA binding is required to either form or stabilize the large loops thought to exist in the chromosome (Fig. 6B). A MukB-ParC complex can be bound to two segments of the DNA simultaneously: one bound to the MukB head domain and the other as the G segment bound across the Topo IV active site. A MukB dimer can span up ∼50 nm in length when the head domain is engaged (35), which would enable the dimer to capture a distal site on the chromosome. It is possible that such a trapped segment is transmitted to the hinge domain, which then opens (36), passing the DNA to Topo IV where it acts as the T segment in the topoisomerization reaction, thereby allowing a topological linkage between two distal segments of DNA. Crossing of the two distal DNA segments could then be stabilized by either the condensin itself or by other proteins. Continuous production of DNA loops stabilized by such crossings could also eventually lead to the structure observed in the electron microscope (34).

MukB is closely associated with the kleisin subunit MukF and MukE, and how they effect the reactions characterized herein is unclear; however, it would be surprising, given that ParC and MukEF interact with different regions of MukB, if MukEF interfered with the effect of ParC. More likely, MukEF influence the loading to and stabilization of MukB on the DNA. Although these proteins are required for stable association of MukB with the chromosome (37), MukB itself can clearly act as a condensing agent in vivo (38), consistent with its ability to induce DNA knotting and supercoiling in the absence of MukEF (15). Although these latter two reactions are inhibited by the presence of MukEF (39), DNA bridging by MukB is modulated but not inhibited by MukEF (40). Clarification of these issues awaits understanding the mechanism of condensin DNA loading both in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolina Gabbai for providing plasmids and Xiaolan Zhao and Joe Yeeles for advice on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM34558 (to K. J. M.)

J. Berger, personal communication.

- Topo IV

- topoiosmerase IV

- TAE

- tris-acetate-EDTA electrophoresis buffer

- (−) sc DNA

- negatively supercoiled DNA

- (+) sc DNA

- positively supercoiled DNA

- MLD

- multiply linked DNA dimers.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vos S. M., Tretter E. M., Schmidt B. H., Berger J. M. (2011) All tangled up: how cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 827–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peng H., Marians K. J. (1993) Decatenation activity of topoisomerase IV during oriC and pBR322 DNA replication in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8571–8575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams D. E., Shekhtman E. M., Zechiedrich E. L., Schmid M. B., Cozzarelli N. R. (1992) The role of topoisomerase IV in partitioning bacterial replicons and the structure of catenated intermediates in DNA replication. Cell 71, 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hiasa H., Marians K. J. (1996) Two distinct modes of strand unlinking during θ-type DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21529–21535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neuman K. C., Charvin G., Bensimon D., Croquette V. (2009) Mechanisms of chiral discrimination by topoisomerase IV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6986–6991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crisona N. J., Strick T. R., Bensimon D., Croquette V., Cozzarelli N. R. (2000) Preferential relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA by E. coli topoisomerase IV in single-molecule and ensemble measurements. Genes Dev. 14, 2881–2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kato J., Nishimura Y., Imamura R., Niki H., Hiraga S., Suzuki H. (1990) New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell 63, 393–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peng H., Marians K. J. (1993) Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV. Purification, characterization, subunit structure, and subunit interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 24481–24490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kato J., Nishimura Y., Yamada M., Suzuki H., Hirota Y. (1988) Gene organization in the region containing a new gene involved in chromosome partition in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 170, 3967–3977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cuylen S., Haering C. H. (2011) Deciphering condensin action during chromosome segregation. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 552–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niki H., Jaffé A., Imamura R., Ogura T., Hiraga S. (1991) The new gene mukB codes for a 177 kd protein with coiled-coil domains involved in chromosome partitioning of E. coli. EMBO J. 10, 183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamanaka K., Ogura T., Niki H., Hiraga S. (1996) Identification of two new genes, mukE and mukF, involved in chromosome partitioning in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250, 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woo J. S., Lim J. H., Shin H. C., Suh M. K., Ku B., Lee K. H., Joo K., Robinson H., Lee J., Park S. Y., Ha N. C., Oh B. H. (2009) Structural studies of a bacterial condensin complex reveal ATP-dependent disruption of intersubunit interactions. Cell 136, 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kimura K., Hirano T. (1997) ATP-dependent positive supercoiling of DNA by 13S condensin: a biochemical implication for chromosome condensation. Cell 90, 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petrushenko Z. M., Lai C. H., Rai R., Rybenkov V. V. (2006) DNA reshaping by MukB. Right-handed knotting, left-handed supercoiling. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4606–4615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stray J. E., Crisona N. J., Belotserkovskii B. P., Lindsley J. E., Cozzarelli N. R. (2005) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Smc2/4 condensin compacts DNA into (+) chiral structures without net supercoiling. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34723–34734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kimura K., Rybenkov V. V., Crisona N. J., Hirano T., Cozzarelli N. R. (1999) 13S condensin actively reconfigures DNA by introducing global positive writhe: implications for chromosome condensation. Cell 98, 239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cuylen S., Metz J., Haering C. H. (2011) Condensin structures chromosomal DNA through topological links. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 894–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayama R., Marians K. J. (2010) Physical and functional interaction between the condensin MukB and the decatenase topoisomerase IV in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18826–18831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y., Stewart N. K., Berger A. J., Vos S., Schoeffler A. J., Berger J. M., Chait B. T., Oakley M. G. (2010) Escherichia coli condensin MukB stimulates topoisomerase IV activity by a direct physical interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18832–18837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heller R. C., Marians K. J. (2005) The disposition of nascent strands at stalled replication forks dictates the pathway of replisome loading during restart. Mol. Cell 17, 733–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hiasa H., Marians K. J. (1994) Tus prevents overreplication of oriC plasmid DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26959–26968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madabhushi R., Marians K. J. (2009) Actin homolog MreB affects chromosome segregation by regulating topoisomerase IV in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell 33, 171–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mossessova E., Levine C., Peng H., Nurse P., Bahng S., Marians K. J. (2000) Mutational analysis of Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV. I. Selection of dominant-negative parE alleles. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4099–4103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bigot S., Marians K. J. (2010) DNA chirality-dependent stimulation of topoisomerase IV activity by the C-terminal AAA+ domain of FtsK. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 3031–3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Y., Schoeffler A. J., Berger J. M., Oakley M. G. (2010) The crystal structure of the hinge domain of the Escherichia coli structural maintenance of chromosomes protein MukB. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marians K. J. (1987) DNA gyrase-catalyzed decatenation of multiply linked DNA dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 10362–10368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wasserman S. A., White J. H., Cozzarelli N. R. (1988) The helical repeat of double-stranded DNA varies as a function of catenation and supercoiling. Nature 334, 448–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bhat M. A., Philp A. V., Glover D. M., Bellen H. J. (1996) Chromatid segregation at anaphase requires the barren product, a novel chromosome-associated protein that interacts with Topoisomerase II. Cell 87, 1103–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maeshima K., Laemmli U. K. (2003) A two-step scaffolding model for mitotic chromosome assembly. Dev. Cell 4, 467–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Uemura T., Ohkura H., Adachi Y., Morino K., Shiozaki K., Yanagida M. (1987) DNA topoisomerase II is required for condensation and separation of mitotic chromosomes in S. pombe. Cell 50, 917–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cuvier O., Hirano T. (2003) A role of topoisomerase II in linking DNA replication to chromosome condensation. J. Cell Biol. 160, 645–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coelho P. A., Queiroz-Machado J., Sunkel C. E. (2003) Condensin-dependent localisation of topoisomerase II to an axial chromosomal structure is required for sister chromatid resolution during mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4763–4776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kavenoff R., Bowen B. C. (1976) Electron microscopy of membrane-free folded chromosomes from Escherichia coli. Chromosoma 59, 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matoba K., Yamazoe M., Mayanagi K., Morikawa K., Hiraga S. (2005) Comparison of MukB homodimer versus MukBEF complex molecular architectures by electron microscopy reveals a higher-order multimerization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 333, 694–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gruber S., Arumugam P., Katou Y., Kuglitsch D., Helmhart W., Shirahige K., Nasmyth K. (2006) Evidence that loading of cohesin onto chromosomes involves opening of its SMC hinge. Cell 127, 523–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. She W., Wang Q., Mordukhova E. A., Rybenkov V. V. (2007) MukEF Is required for stable association of MukB with the chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7062–7068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Q., Mordukhova E. A., Edwards A. L., Rybenkov V. V. (2006) Chromosome condensation in the absence of the non-SMC subunits of MukBEF. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4431–4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Petrushenko Z. M., Lai C. H., Rybenkov V. V. (2006) Antagonistic interactions of kleisins and DNA with bacterial Condensin MukB. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34208–34217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Petrushenko Z. M., Cui Y., She W., Rybenkov V. V. (2010) Mechanics of DNA bridging by bacterial condensin MukBEF in vitro and in singulo. EMBO J. 29, 1126–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]