Background: Humanization of murine monoclonal antibodies by CDR grafting is a widely used technique.

Results: In vitro somatic hypermutation was coupled with minimal CDR grafting to produce potent, pm affinity antibodies.

Conclusion: This methodology can rapidly generate potent, humanized antibodies containing a minimum of donor sequence.

Significance: Antibodies produced using this approach contain reduced rodent antibody donor content and possess potential advantages in manufacturability and immunogenicity.

Keywords: Antibodies, Antigen, Cell Signaling, Protein Engineering, Protein Evolution, CDR Grafting, Humanization

Abstract

A method for simultaneous humanization and affinity maturation of monoclonal antibodies has been developed using heavy chain complementarity-determining region (CDR) 3 grafting combined with somatic hypermutation in vitro. To minimize the amount of murine antibody-derived antibody sequence used during humanization, only the CDR3 region from a murine antibody that recognizes the cytokine hβNGF was grafted into a nonhomologous human germ line V region. The resulting CDR3-grafted HC was paired with a CDR-grafted light chain, displayed on the surface of HEK293 cells, and matured using in vitro somatic hypermutation. A high affinity humanized antibody was derived that was considerably more potent than the parental antibody, possessed a low pm dissociation constant, and demonstrated potent inhibition of hβNGF activity in vitro. The resulting antibody contained half the heavy chain murine donor sequence compared with the same antibody humanized using traditional methods.

Introduction

The majority of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies approved by the Food and Drug Administration for human use are derived from mouse immunization, with 21 of the 30 marketed molecules originating from murine hybridoma sources (1). Hybridoma-derived monoclonal antibodies possessing desired functional properties are typically humanized by replacing those regions not required for antigen binding specificity with the corresponding human sequence. The goal of this process is to produce a molecule with reduced nonhuman sequence content that possesses the same or improved activity and affinity relative to the parent antibody but with reduced immunogenicity. The first methods developed replaced the constant domains of the mouse donor antibody to produce a chimeric molecule that was ∼70% human sequence (2). Subsequently, both the constant domains and variable domain framework regions were replaced with human sequence, leading to complementarity determining region (CDR)-grafted2 antibodies with ∼90% human antibody sequence (3, 4).

CDR-grafted antibodies often exhibit reduced binding affinity, and additional engineering is generally required to recover the binding properties of the original clone. Structure-based (5–7) and library-based methods (8) have been demonstrated for antibody humanization that regain or may improve upon the binding affinity of the originating molecule. Affinity maturation of antibodies can be accomplished by a number of methods including random mutagenesis (9, 10), random mutagenesis of CDR sequences (11), directed mutagenesis of residues (12, 13), and approaches that reproduce SHM in vitro (14). Random methods for humanization and affinity maturation rely on multiple rounds of labor-intensive trial and error mutagenesis, and may result in an additional non-germ line sequence being incorporated into the final antibody.

During in vivo adaptive immunity, affinity maturation in B-cells is effected by Ig SHM combined with clonal selection. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) is the enzyme that initiates SHM, and its action, in concert with additional, ancillary factors, introduces mutations into the DNA of antibody V regions, preferentially targeting amino acids important for antigen binding such as those capable of direct contact with antigen. The position and identity of SHM mutations have been explored in detail by a number of groups and have led to the identification of specific hot spot motifs (e.g., WRCH) (15). Expression of AID in either a B-cell or non-B-cell context in vitro has been shown to be sufficient to initiate SHM and results in replication of the amino acid diversity generated by SHM in vivo (16–18).

We sought to develop a simple method for humanization that would minimize both the originating murine-derived antibody sequence and secondary mutations required for affinity maturation, while improving upon the affinity and activity of the originating antibody. The CDR H3 of a murine antibody, directed against the neurotrophic growth factor hβNGF was grafted into a nonhomologous human V region and affinity-matured in vitro utilizing a combination of AID-directed SHM activity in HEK293 cells and also libraries exploring common SHM events observed in vivo. This approach resulted in the rapid generation of a humanized antibody with pm affinity for hβNGF that exhibited potent anti-hβNGF in vitro and possessed half the number of non-germ line HC mutations and donor antibody sequence compared with the same antibody humanized using traditional methods.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Analysis of in Vivo Somatic Hypermutation

The NCBI archive of antibody sequences was downloaded from NCBI and mined for sequences annotated as human IgG or IgM in origin. Germ line human IGHV, IGKV, and IGLV sequences and their allelic forms were assembled from three online antibody sequence sources, IMGT, NCBI Entrez, and VBASE, yielding a total of 232 IGHV, 56 IGKV, and 66 IGLV germ line alleles. The single germ line sequence that provided the best unique alignment to each of the matured antibody sequences was identified using an ungapped BLAST alignment with an expectation score of <1.0 × 10−50 and a minimum 93% sequence identity over the entire length of the antibody variable region. Mutations identified at the 5′ and 3′ portions (three residues) of the alignment were not considered further in this analysis. In this way, a total of 106909 IGHV, 24378 IGKV, and 24965 IGLV mutations were identified in 12956, 4165, and 3811 alignments to germ line sequences, respectively. Each DNA base in the germ line sequences was mapped to a unique codon and Kabat numbering position, making later analysis of amino acid and codon mutagenesis possible.

Assembly of the SHM Diversified Libraries

The CDR3-grafted CDR1,2 SHM diversified heavy chain library used for initiation of humanization was synthesized as previously described (19) with the germ line IGHV3–23 nucleic acid sequence serving as its basis (5′-ATGGAGTTTGGGCTGAGCTGGCTTTTTCTTGTGGCTATTTTAAAAGGTGTCCAGTGTGAGGTGCAGCTGTTGGAGTCTGGGGGAGGCTTGGTACAGCCTGGGGGGTCCCTGAGACTCTCCTGTGCAGCCTCTGGATTCACCTTTAGCAGCTATGCCATGAGCTGGGTCCGCCAGGCTCCAGGGAAGGGGCTGGAGTGGGTCTCAGCTATTAGTGGTAGTGGTGGTAGCACATACTACGCAGACTCCGTGAAGGGCCGGTTCACCATCTCCAGAGACAATTCCAAGAACACGCTGTATCTGCAAATGAACAGCCTGAGAGCCGAGGACACGGCCGTATATTACTGTGCGAGA-3′. The DNA sequence for H3 was taken directly from the αD11 HC CDR3 sequence as published, and the FW4 sequence was taken from the closest human J-region IGHJ6 (5′-TGGGGGCAAGGGACCACGGTCACCGTCTCCTCA-3′). Kabat CDR definitions were used, and germ line sequences were based on IMGT database annotations (20, 21). Amino acid positions selected for diversification and the amino acid diversity at each position (Fig. 1) in this HC library were based on the bioinformatics analysis described above. The amino acids encoded in the library at each position were: H28, TAIS; H30, STGN; H31, SNDIRT; H33, ATSVG; H35, NGTIS; H50, AGTSLV; H52a, GDVANT; H53, SRNTG; H55, AVRTDS; and H56, SRTGN. The germ line residue Gly-55 was not present in the library. The codons used to encode amino acid diversity at each position (Ser, AGC; Thr, ACT, Ala, GCT, Asn, AAC; Val, GTC; Arg, AGG; Ile, ATC; Asp, GAC; and Leu, CTG) were selected based on two criteria: observed codon usage at antigen contacting positions across all IGV genes and preservation of AID hot spots (WRC). The HC CDR3-grafted, CDR1,2 diversified library was assembled with IgG1 constant domains with a C-terminal transmembrane segment supporting cell surface display and cloned into in-house episomal vectors for stable selection in HEK293 cells.

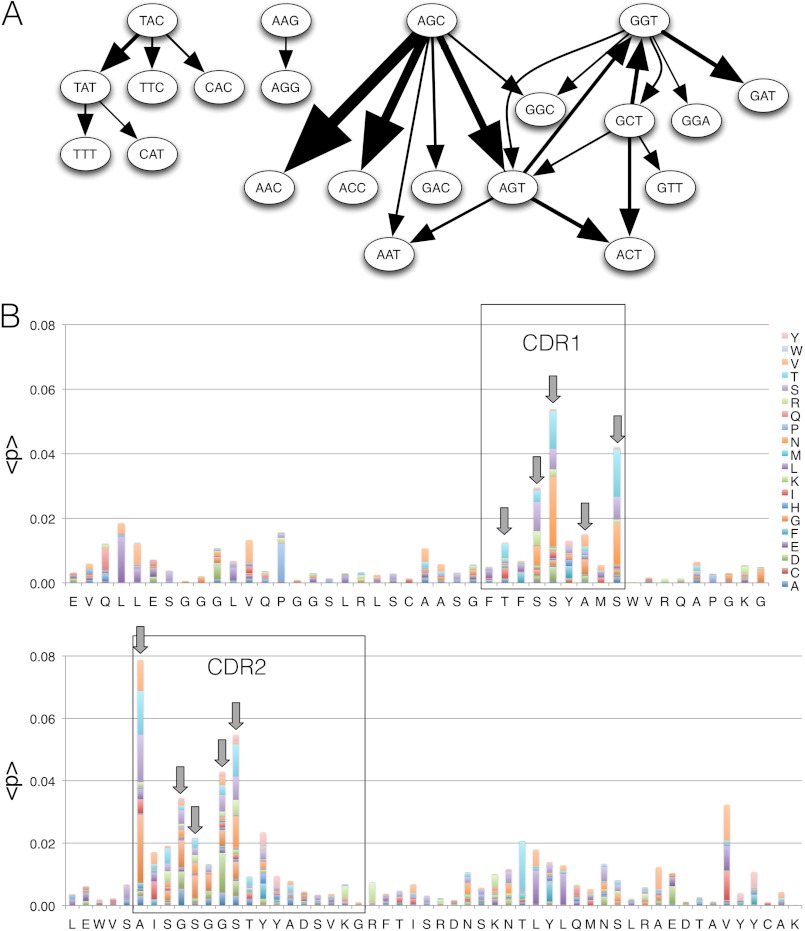

FIGURE 1.

SHM in vivo. Analysis of human affinity-matured antibodies compared with their germ line antecedents highlights the features of SHM in vivo. The 20 most common codon mutations are shown for the IGHV 3–23 V region (A). The arrow widths are proportional to the frequency with which a mutation of a codon was observed (e.g., AGC to AAC corresponds to 3529 events). Common in vivo SHM events form an interconnected network of differentiation seeded from SHM AID hot spots that correspond to antigen contacting positions (B). Specific IGHV positions account for a majority of the diversity created during in vivo affinity maturation. Mutations at 10 CDR1 and CDR2 positions, denoted by arrows, were selected for a combinatorial library containing 6E6 members, accounting for ∼30% of all in vivo SHM events observed in this V region.

The LC V region sequence was assembled using the germ line sequence for the closest human V gene homolog IGKV1–27 (leader peptide and FW1, 5′-ATGGACATGAGGGTCCCTGCTCAGCTCCTGGGACTCCTGCTGCTCTGGCTCCCAGATACCAGATGTGACATCCAGATGACCCAGTCTCCATCCTCCCTGTCTGCATCTGTAGGAGACAGAGTCACCATCACTTGC-3′; FW2, 5′-TATCAGCAGAAACCAGGGAAAGTTCCTAAGCTCCTGATCTAT-3′; and FW3, 5′-GGGGTCCCATCTCGGTTCAGTGGCAGTGGATCTGGGACAGATTTCACTCTCACCATCAGCAGCCTGCAGCCTGAAGATGTTGCAACTTATTACTGT-3′) and IGKJ1 (FW4, 5′-TGGACGTTCGGCCAAGGGACCAAGGTGGAAATCAAA-3′). CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3 LC DNA sequences were taken from αD11 LC published sequence, with boundaries as defined by Kabat CDR definitions. The entire sequence was synthesized (DNA2.0, Menlo Park, CA) and joined with a human IGK constant domain and assembled in in-house episomal vectors.

Two light chain V region libraries, termed ML28 and ML30, were also prepared during affinity maturation. They were also based on the most frequently observed SHM events in antibody light chains as described for heavy chains. Both contained variations at three positions. ML28 contained ERHQGK at position 27, DGANTSPR at position 28, and NGDAS at position 50, whereas ML30 contained ANFSYDT at position 32, TNRS at position 53, and HAEQ at position 55.

Transformation, Stable Expression, and Selection of HEK293 c18 Cells

HEK293 c18 cell lines stably expressing the CDR3-grafted, IgG heavy chains modified with a C-terminal transmembrane domain (22) and CDR1,2,3-grafted light chain, together with AID were generated using individual episomal vectors under independent selection for expression of HC, LC, and AID as described (14). T75 culture flasks were seeded with 3 × 106 HEK293 c18 cells in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen). Plasmids were transfected using OptiMEM (Invitrogen) and HD-FuGENE (Roche Applied Science). Three days post-transfection, cell growth medium was exchanged with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 50 μg/ml geneticin, 10 μl/ml antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 1.5 μg/ml puromycin, 15 μg/ml blasticidin, and/or 350 μg/ml hygromycin (all from Invitrogen), and the cells were incubated for approximately 4 weeks with periodic reseeding and exchange of the cell culture medium.

Antigen and Antibody Expression and Purification

Antibody variants were expressed transiently in HEK293 c18 cells as full-length IgG1 kappa molecules. Supernatants from transfected cells were loaded on a protein A/G-agarose resin (Thermo Scientific), washed with 6 column volumes of PBS, pH 7.4, and eluted with 100 mm glycine, pH 3.0, with the resulting purified IgGs buffer exchanged into PBS. Human hβNGF was expressed transiently in HEK293 c18 cells and purified using standard His tag affinity purification methodologies. Fluorescently labeled antigens utilized for FACS were prepared using standard amine coupling chemistry. In addition, a fusion protein of hβNGF linked to wasabi fluorescent protein was also expressed and purified using standard His tag affinity purification methods.

FACS Selection

To assess initial antigen binding and optimal conditions for FACS, HEK293 c18 cells displaying cell-surface antibody (5 × 105 cells in 0.5 ml PBS, 0.1% BSA) were incubated with various concentrations of fluorescently tagged hβNGF and FITC-AffiniPure Fab fragment goat anti-human IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 0.5 h at 4 °C. The cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 0.3 ml of 0.2 μg/ml DAPI in PBS, 0.1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed for fluorescence on a BD Influx cell sorter (BD Biosciences). For FACS selection, stably transfected HEK293 c18 cells were incubated with fluorescently tagged hβNGF (at concentrations determined empirically from FACS analysis discussed above). In each instance, ∼20–40 million cells were sorted, typically selecting 0.1–0.5% of the most fluorescent cells normalized against cell surface IgG expression. The amino acid composition of the HC and LC in the final populations was assessed via Sanger sequencing from cell pellets collected following each FACS selection.

HTRF Antibody Competition Assay

The binding affinity rank order of anti-NGF antibodies was determined in an HTRF assay. A reference antibody to hβNGF (tanezumab) was biotinylated, and purified hβNGF was labeled with N-hydroxysuccinimide activated cryptate using a HTRF® cryptate labeling kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Cisbio Bioassays). The biotinylated reference antibody was mixed with Streptavidin-XL665 (Cisbio), with the test antibody added at varied concentrations, followed by incubation with labeled hβNGF at room temperature for 2.5 min in PBS, pH 7.2, 0.1% BSA. The reaction was read in a ProxiPlate-384 Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) (320-nm excitation, dual emission at 620 and 665 nm). Binding of hβNGF to the reference antibody was represented as the ratio of emission at 665/620 nm. To determine the IC50 values of the test antibodies, the 665/620-nm emission ratios were fitted by a three-parameter inhibitory curve using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

NGF Signaling Assay

The rat pheochromocytoma-derived cell line, PC12, that differentiates in response to hβNGF (23) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-1721) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 15% horse serum, 2.5% FBS. For signaling assays PC12 cells were plated at 0.8–1.0 × 105 cells/well in collagen type IV coated 96-well microplates (BD BioCoatTM; BD Biosciences) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Following a 4-h serum starvation in DMEM, 0.1% BSA PC12 cells were stimulated with human hβNGF (R&D Systems, 10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of various concentrations of anti-βNGF antibodies for 15 min at 37 °C. Cell lysates were made in freshly prepared 1× lysis buffer for AlphaScreen® (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions for adherent cells. Activated ERK1/2 in cell lysates was quantified in an AlphaScreen® SureFire® p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) Assay (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions for adherent cells. The plates were read on an EnVision® 2103 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The data were graphed and analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.) using three-paramter, nonlinear regression curve fits.

Affinity Screening of Antibody/βNGF Binding

Secreted antibodies from 96-well plate array transfections were screened and ranked using a Biacore 4000 (GE Healthcare) surface plasmon resonance (SPR) instrument. Four of five spots in four flow cells on a Series S CM5 chip (GE Healthcare) were coupled with ∼10,000 resonance units of anti-human IgG (Fc) (human antibody capture kit; GE Healthcare). The fifth flow cell was kept blank to serve as a reference. Culture medium from antibody transfected HEK293 cells was diluted 1:1 with HBS-EP+ buffer (10 mm HEPES, 150 mm sodium chloride, 3 mm EDTA, 0.05% Polysorbate 20) with 0.1% BSA, pH 8.0, and centrifuged. Secreted antibody was captured on the CM5 chip by flowing diluted culture medium over the outer spots for 120 s at 10 ml/min. hβNGF at 500 and 50 nm was then passed over all flow cells for 120 s at 30 ml/min and then allowed to dissociate for 600 s. The capture surface was regenerated using glycine, pH 1.5, for 120 s. Resulting sensorgrams were double reference subtracted, and the kinetics were analyzed using Biacore 4000 evaluation software, version 1.0.

Antibody variants exhibiting the highest affinity binding by Biacore 4000 analysis were chosen for scale-up, purification, and additional characterization of kinetic constants using a Biacore T200 (GE Healthcare). Each of four flow cells on a Series S CM5 chip was immobilized with ∼1,000 resonance units of anti-human IgG (Fc). Antibodies (∼1 mg/ml) were captured for 60 s at a flow rate of 10 ml/min. hβNGF was diluted in running buffer (HBS-EP+, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4) starting ∼10-fold higher concentration than each antibody's KD. Each hβNGF concentration was passed over all flow cells for 120 s at 30 ml/min, then allowed to dissociate for 600 s. Surfaces were regenerated with 3 m MgCl2 for 180 s. Association and dissociation kinetic constants (kon and koff) and steady-state affinity (KD) were derived from the resulting sensorgrams using Biacore T200 evaluation software, version 1.0.

Sanger Sequencing

DNA templates were rescued from 3.3 × 104 cells by PCR amplification using Accuprime PFX polymerase for 25–30 cycles. Oligonucleotide primers were used that encompass from ∼140 nucleotides 5′ to the ATG start codon through 30 nucleotides 3′ to the junction of the variable/constant regions, to yield amplicons of ∼550 nucleotides in length for both HC and LC.

RESULTS

Analysis of SHM in Vivo

Humanization was initiated by grafting the CDR H3 from a rat monoclonal antibody to hβNGF (24) into a nonhomologus V region (Fig. 2). A combinatorial HC V region library with amino acid variation at ten CDR1 and two positions was used to initiate grafting prior to in vitro SHM and affinity maturation. The V gene IGHV3–23 was chosen for CDR3 grafting based on its good biophysical characteristics, its use in existing therapeutics, and its high degree of usage in human in vivo antibody repertoires. Positions were varied to encompass the most frequent in vivo SHM events observed in the IGHV3–23 gene. Mutations resulting from in vivo SHM were obtained by comparing matured human antibody sequences with their corresponding germ line V gene sequences. A total of 106,909 IGHV, 24,378 IGKV, and 24,965 IGLV mutations were identified in 12956, 4165, and 3811 alignments to germ line V gene sequences, respectively. These data can be viewed as a fate map of likely mutations observed during in vivo SHM (Fig. 1A), revealing that particular SHM hot spots (e.g., AGC) propagate the majority of amino acid diversity. Hot spot motifs are often localized to antigen contacting residues, contained primarily within CDR1, CDR2, and FW3, as shown for the V gene IGHV3–23 in Fig. 1B. This analysis was applied to create the V gene combinatorial library with variability at ten positions within CDR1 and CDR2 as described under “Experimental Procedures” (Fig. 3). The library encoded four to six possible codons at each varied position and had a total complexity of 1.6E+07 members, reflecting the most common V gene, position-specific amino acid mutations as described above.

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of humanization approach. The CDR H3 of a murine antibody (A) is grafted into a nonhomologous human V region. Canonical antigen-contacting residues in the HC CDR1 and CDR2 are varied a combinatorial library designed to mirror common SHM events observed in vivo. The HC is paired with a CDR-grafted LC, transfected with AID in HEK293 cells (B). AID-mediated SHM paired with iterative rounds of FACS resulted in the rapid generation of a humanized antibody (C) with high affinity for its antigen and a minimum of donor antibody sequence. Grafted H3, L1, L2, and L3 CDR loops are shown in green, HC positions varied in the combinatorial library are shown in blue, and AID-derived mutations are shown in magenta.

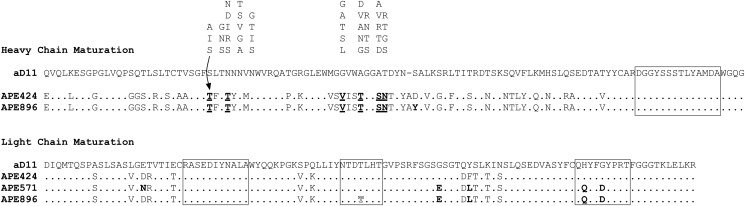

FIGURE 3.

Sequence diagram of CDR grafting and affinity maturation. The diagram shows the evolution of HC and LC sequences during humanization and affinity maturation, with amino acids annotated as follows: residues contained within the boxes are derived from L1, L2, L3, and H3 grafting of αD11; residues in bold and underlined originate from mutations obtained from the CDR1 and CDR2 SHM-diversified library that accompanied grafting; residues annotated in bold only highlight AID-mediated affinity maturation events incorporated during in vitro SHM; and residues shown as outlines correspond to mutations obtained from small SHM-diversified combinatorial libraries in L1 and L2. Amino acid mutations included in the HC CDR1 and CDR2 SHM-diversified combinatorial library are shown above the relevant residues positions as indicated by the arrow.

CDR H3 Grafting in V Region SHM Diversified Libraries for Humanization

To initiate humanization, the combinatorial IGHV3–23 library described above was paired with a LC containing the originating antibody L1, L2, and L3 CDRs grafted into its closest human κ V region ortholog (IGKV1–27). The library was assembled in episomes in a full-length IgG1 format that supports simultaneous secretion and cell surface display in mammalian cells (14).

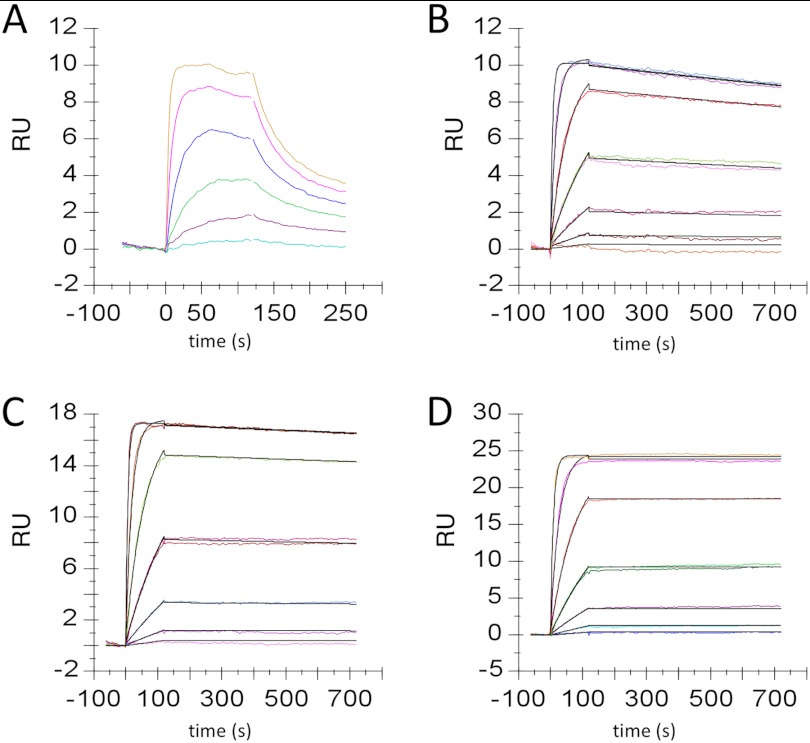

Following transfection and stable episomal selection in HEK293 cells, the cell population was expanded and subjected to iterative rounds of FACS (Fig. 2). To apply selective pressure, the cells were stained with diminishing concentrations of fluorescently labeled antigen. Single cells were sorted into 96-well plates, and kinetics of antibody-antigen binding was characterized (from conditioned media containing secreted antibody) by SPR. Four distinct HC sequences paired with the CDR-grafted LC were isolated from 60 single cell clones, with dissociation constants ranging from 2 to 15 nm. The clone possessing the highest affinity (APE424) contained eight differences from the IGHV3–23 germ line and differed in sequence at 43 V region positions relative to the starting rat HC and at 17 of 26 positions within CDR1 and 2 (Fig. 3). APE424 possessed an affinity of 2 nm, 10-fold weaker than the starting murine antibody and 3-fold weaker than αD11 HC and LC CDRs 1, 2, and 3 grafted into their closest human V gene homologs IGHV4–59 and IGKV1–27 (αD11 graft) (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

TABLE 1.

SPR analysis of binding kinetics

Association and dissociation kinetic constants (kon and koff) for each variant were obtained from a best fit of 1:1 binding of the sensorgrams using Biacore T200 evaluation software version 1.0 (B). The dissociation rate for APE424 is 1.7 s−1, which was subsequently improved ∼1000-fold by four AID-derived mutations identified during affinity maturation (APE894, APE896, and APE897).

| Antibody | kon | koff | KD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/Ms | 1/s | m | |

| αD11 | 2.0E + 05 | 2.4E-04 | 8.3E-10 |

| αD11 graft | 1.8E + 05 | 4.7E-05 | 3.8E-10 |

| APE424 | 7.3E + 06 | 1.7E-02 | 2.3E-09 |

| APE520 | 9.3E + 06 | 1.9E-04 | 2.1E-11 |

| APE571 | 1.6E + 07a | 7.2E-05 | 4.5E-12a (<1E-11) |

| APE890 | 9.4E + 06 | 3.9E-05a | 4.2E-12a (<1E-11) |

| APE894 | 8.7E + 06 | 1.9E-05a | 2.2E-12a (<1E-11) |

| APE896 | 6.5E + 06 | 6.4E-08a | 9.9E-15a (<1E-11) |

| APE897 | 9.1E + 06 | 1.7E-05a | 1.8E-12a (<1E-11) |

| PG110 | 4.7E + 06 | 1.9E-07a | 4.0E-14a (<1E-11) |

a These values are considered to be at or below the level of detection for this instrument.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of antibody binding Kinetics. SPR sensorgrams are shown for the initial clone isolated from the SHM-diversified, H3-grafted library, APE424 (A) and for affinity-matured variants APE520 (B), APE571 (C), and APE896 (D). Association for all antibodies is at or near the diffusion-limited rate for proteins of this size (∼1E7 m−1s−1). RU, resonance units.

Affinity Maturation

APE424 was affinity-matured using two parallel strategies: in vitro SHM initiated by transfection of AID and small combinatorial libraries incorporating the most frequent in vivo SHM events in the LC CDR1 and 2. In the first approach, the HC and LC were stably transfected with AID into HEK293 cells as described (14). In the second approach, positions within the LC CDR1 and CDR2 were varied in combinatorial libraries to identify beneficial mutations. The two LC libraries (ML28 and ML30) encompassed a total of 6 L1 and L2 antigen-contacting positions with mutations frequently observed during SHM in vivo. As with the AID-mediated SHM approach, these libraries were paired with the APE424 HC, transfected with AID in HEK293 cells, stably selected, and subjected to 4–6 rounds of cell sorting in the presence of diminishing concentrations of fluorescently labeled antigen.

Affinity maturation was observed within two rounds of cell sorting from the in vitro SHM strategy, as evidenced by enriched mutations observed in sequences recovered from cells binding antigen with higher affinity (Table 2). Mutations identified from this cell population were recombined by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis, expressed, and characterized by SPR. A construct incorporating LC mutations G66E, H90Q, and G93D (APE520) showed a 100-fold improvement in binding affinity for hβNGF relative to APE424, and the addition of LC mutations D17N and F71L improved affinity by an additional 4-fold (AP571) (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 4). An additional mutation, D61Y, was observed to be enriched in the HC and was included in the final library used to recombine the SHM-derived mutations described below.

TABLE 2.

Mutations accompanying affinity maturation

The origin of mutations acquired from human germ line during humanization and maturation of the antibody is described. The Kabat position and chain where the mutation was observed is shown in the first and second columns, respectively. The starting and ending amino acids are shown in the third and fourth columns. The sources of the mutations are show in the fifth column (M2: CDR1, 2 SHM-diversified combinatorial HC library; and AID: AID-derived in vitro SHM, ML28, and ML30 small CDR1 and CDR2 LC combinatorial libraries). The structural locations of mutations are shown in the sixth column. The mutations present in antibodies APE424, APE520, APE571, APE890, APE896, and APE897 are designated in the seventh through the twelfth columns.

| Origin | Kabat | Chain | Amino acid | Mutation | Source | Position | APE424 | APE520 | APE571 | APE890 | APE896 | APE897 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library | 30 | HC | Ser | Thr | M2 | CDR1 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 31 | HC | Ser | Thr | M2 | CDR1 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 33 | HC | Ala | Asn | M2 | CDR1 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 50 | HC | Ala | Val | M2 | CDR2 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 52A | HC | Gly | Thr | M2 | CDR2 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 53 | HC | Ser | Gly | M2 | CDR2 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 55 | HC | Gly | Ser | M2 | CDR2 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Library | 56 | HC | Ser | Asn | M2 | CDR2 | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| AID | 61 | HC | Asp | Tyr | AID | CDR2 | × | × | ||||

| AID | 17 | LC | Asp | Asn | AID | FW1 | × | × | ||||

| AID | 66 | LC | Gly | Glu | AID | CDR2 | × | × | × | × | × | |

| AID | 71 | LC | Phe | Leu | AID | FW3 | × | × | × | × | ||

| AID | 90 | LC | His | Gln | AID | CDR3 | × | × | × | × | × | |

| AID | 93 | LC | Gly | Asp | AID | CDR3 | × | × | × | × | × | |

| AID | 53 | LC | Thr | Arg-Thr | ML30 | CDR2 | × | × |

Mutations were enriched from both LC SHM-diversified libraries, including CDR1 mutations E27K and N28D, and CDR2 mutations T53R and H55Q, each providing only modest (<2-fold) improvements in affinity. Transfection of AID into the library cells resulted in additional mutations generated, and the AID-mediated mutation H90Q was also enriched by round 2 of cell sorting. To identify the optimal HC and LC from the enriched mutations identified, mutations from the in vitro SHM and SHM-diversified library strategies were recombined by overlap extension PCR in a final combinatorial library, which was transfected and stably selected in HEK293 cells. This population was subjected to iterative rounds of fluorescence-activated cell sorting using diminishing concentrations of antigen. In FACS rounds 4 and 5, the cells were incubated with 1 nm Dylight-labeled antigen for 30 min, followed by washing and incubation with unlabeled hβNGF (25). Following round 5, the cells were isolated by FACS, HC/LC pairs were isolated, the corresponding antibodies were expressed and purified, and binding kinetics were characterized by SPR.

Characterization of Affinity-matured Antibody Variants

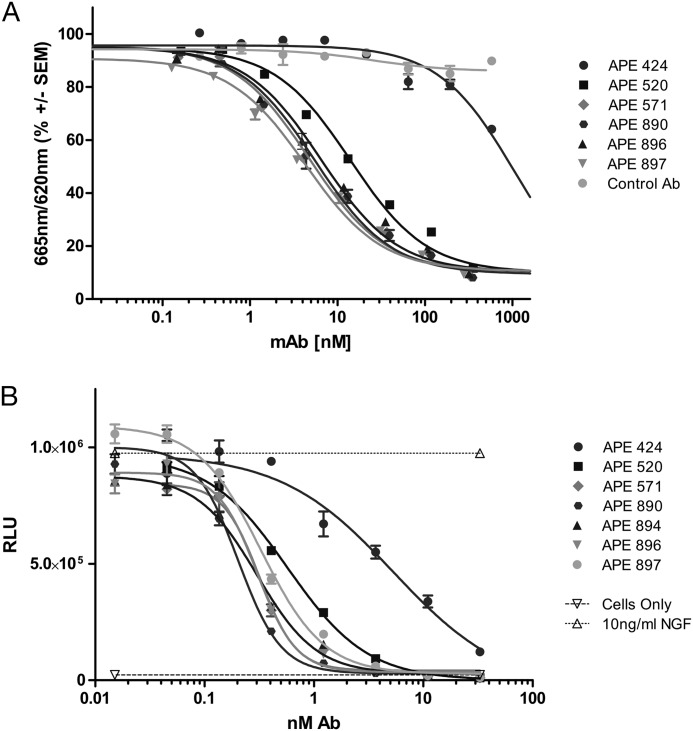

The binding kinetics and KD of affinity-matured antibodies were determined to be in the mid to low pm range as determined by SPR experiments (Table 1 and Fig. 4), with koff values at or below the limit of detection (∼1E-05 s−1). Parental and affinity-matured variants were analyzed for their ability to block hβNGF binding to and activation of its cognate receptor TrkA in two assays: competition for binding to hβNGF with a known receptor blocking anti-βNGF antibody (tanezumab) and inhibition of hβNGF-dependent TrkA signaling in a rat pheochromocytoma-derived cell line (PC12). Antibody APE424 inhibited binding of tanezumab to hβNGF in a HTRF assay with an IC50 of ∼1 μm (Fig. 5A). The affinity improvement observed among the recombined antibody variants was well matched to their improved potency, with antibody APE897 possessing an IC50 value of 4 nm (250-fold improvement) in the HTRF assay. Parental and affinity-matured variants were also analyzed for their ability to demonstrate dose-dependent inhibition of hβNGF-induced TrkA signaling and activation of ERK1/2 in PC12 cells (Fig. 5B). Again, the final affinity-matured variants (e.g., APE890; IC50 = 300 pm) showed significant improvement relative to the starting construct (APE424; IC50 = 10 nm) in their ability to inhibit PC12 signaling, which mirrors the improvement in affinity as measured by SPR.

FIGURE 5.

Sensorgrams of affinity-matured variants. Initial (APE424) and affinity-matured antibodies were characterized in an HTRF assay for their ability to inhibit binding of tanezumab, an anti-hβNGF antibody (A). Starting and affinity-matured variants were also tested for their ability to inhibit hβNGF-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation in neuronal PC12 cells (23) (B). In each instance, dose-dependent inhibition of hβNGF activity was demonstrated that mirrored affinity improvements as measured by SPR. RLU, relative luminescence units.

Amino Acid Sequences of the Final Antibody Constructs

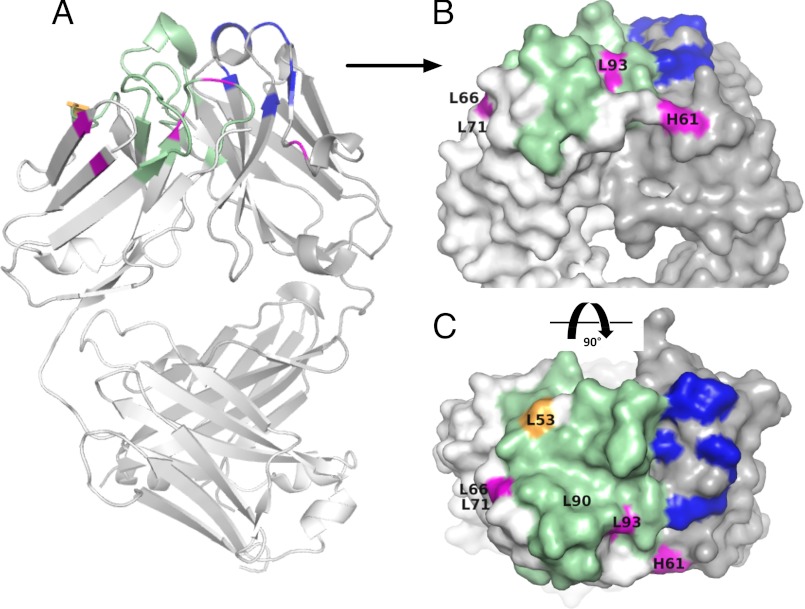

The amino acid changes in the highest affinity recombined antibody HC and LCs are shown in Fig. 6 on a model of the Fab structure. In Fig. 6A, sequences originating from mouse hybridoma and human germ line sources are highlighted in a ribbon diagram of the modeled Fab. In Fig. 6, B and C, the origin of mutations is illustrated in a spacing filling model, illustrated by different colors, with contributions from CDR grafting, SHM-diversified libraries, and in vitro AID-mediated SHM. Only one of the library-derived LC mutations was included in the final construct, with a majority of the affinity maturation events (five of six) derived from AID-mediated mutations in the LC, particularly within FW2 and FW3 regions. These sites do not correspond to previously identified mutations shown to facilitate humanization (5).

FIGURE 6.

Structural models of incorporated mutations. Ribbon (A) and space filling models (B and C) of the humanized, affinity-matured antibody APE896 are shown based on the Protein Data Bank structure 1ZAN (33). Amino acids colored green are derived from L1, L2, L3, and H3 grafting, residues colored in blue originate from mutations obtained from the CDR1 and CDR2 SHM-diversified library that accompanied grafting, residues in magenta highlight AID-mediated affinity maturation events incorporated during in vitro SHM, and the orange residue corresponds to a mutation obtained from small SHM-diversified combinatorial libraries in L1 and L2. Lettering annotates the chain (L, light; H, heavy) and Kabat position of the observed mutation (e.g., L53).

DISCUSSION

A novel method has been developed for the humanization and efficient affinity maturation of antibodies. The CDR H3 of a rat antibody was grafted into a nonhomologous human V region containing CDR H1 and H2 residues varied to mimic in vivo SHM diversity. The HC library was paired with a CDR-grafted LC and presented as a full-length IgG on the surface of HEK293 cells. Cells expressing low affinity antibodies were isolated by FACS and affinity-matured rapidly using SHM in vitro, resulting in high potency antibodies with pm affinity. From the perspective of therapeutic antibody development, this approach has the advantage of enabling the rapid humanization of functional high potency antibodies containing a minimum of nonhuman donor antibody-derived sequence. The adaptive nature of this methodology should also facilitate the use of human V genes possessing lower homology to the murine antecedent, and the successful humanization of CDR-grafted constructs possessing lower starting affinities for the antigen.

The method of pairing mammalian display with in vitro SHM to affinity-matured antibodies could likely be applied in other venues. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of computational methods to design grafted or de novo libraries of proteins with the desired binding properties (26–28). One or more loops of a donor antigen have been grafted onto a soluble surrogate scaffold protein for application in immunization and directed evolution. Likewise, novel binding proteins have been designed de novo utilizing only computational methods. In each instance, library ensembles of related molecules are first screened to resolve minority populations possessing desired functionality from nonbinding or nonfunctional members. As with the humanization example presented here, pairing in vitro SHM with mammalian display should provide a powerful tool for the rapid interrogation and subsequent affinity maturation of computationally derived binding proteins.

The originating rat hybridoma antibody has been independently humanized and affinity-matured (PG110) and has completed phase I clinical trials for the indication of pain associated with osteoarthritis of the knee (29). Antibody APE896, derived from the same original monoclonal antibody, possessed half the number of IGHV non-germ line mutations when compared with PG110 (9 mutations localized to CDR1 and CDR2 for APE896 versus 20 mutations found in FW1, CDR1, FW2, CDR2, and FW3 for PG110), possessed sequence identity of 89% with the closest human germ line sequence throughout the HC and LC V regions (versus 80% for PG110), and possessed an affinity equivalent to that of PG110 (Table 1). In addition, because this method minimizes the number of mutations needed to humanize and affinity-mature an antibody, the APE896 HC possessed greater sequence identity to its parental V gene segment (IGHV3–23) (89%) than did the original hybridoma rat V region sequence to either its originating rat germ line segment (86%) or to the closest human V gene IGHV4–59 (60%). The adaptive nature of the methodology and its ability to mature antibodies to high potency facilitates the use of human V regions with distant homology to the originating murine sequence, providing more flexibility in gene selection based on additional criteria such as manufacturability and known expression characteristics (30).

A HC V region library informed by likely SHM events observed in vivo was utilized to initiate affinity maturation of the CDR-grafted antibody, and similar libraries have been employed to effect modest affinity maturation when paired with phage and other display technologies (31, 32). In this instance, significant additional maturation was required, and AID-mediated in vitro SHM was successful in the identification of a small number of mutations (Table 2) that when combined improved the affinity of APE424 to low pm. Mutations selected by in vitro SHM to enhance binding kinetics were at positions unanticipated by bioinformatics analysis and not associated with canonical antigen contacting positions or hot spots (e.g., HC mutations D17N, G66E, and F71L and LC mutation D61Y). These results demonstrate that in vitro SHM, coupled with minimal CDR grafting, can be sufficient for rapid humanization and affinity maturation to generate potent antibodies containing a minimum of sequence from the nonhuman donor antibody.

All authors associated with this manuscript work for Anaptysbio Inc. and receive a salary, stock, and/or stock options as part of their employment. The scientific work presented in this paper is one part of the Anaptysbio platform and technology.

- CDR

- complementarity-determining region

- SHM

- somatic hypermutation

- AID

- activation-induced cytidine deaminase

- HC

- heavy chain

- LC

- light chain

- IGHV

- immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region

- IGLV

- immunoglobulin λ variable region

- IGKV

- immunoglobulin κ variable region

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- HTRF

- homogenous time-resolved fluorescence

- hβNGF

- human β NGF

- H1

- HC CDR1

- H2

- HC CDR2

- H3

- HC CDR3

- L1

- LC CDR1

- L2

- LC CDR2

- L3

- LC CDR3.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reichert J. M., (2011) Antibody-based therapeutics to watch in 2011. mAbs 3, 76–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrison S. L., Johnson M. J., Herzenberg L. A., Oi V. T. (1984) Chimeric antibody molecules. Mouse antigen-binding domains with human constant region domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 6851–6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones P. T., Dear P. H., Foote J., Neuberger M. S., Winter G. (1986) Replacing the complementarity-determining regions in a human antibody with those from a mouse. Nature 321, 522–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verhoeyen M., Milstein C., Winter G. (1988) Reshaping human antibodies. Grafting an antilysozyme activity. Science 239, 1534–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Queen C., Schneider W. P., Selick H. E., Payne P. W., Landolfi N. F., Duncan J. F., Avdalovic N. M., Levitt M., Junghans R. P., Waldmann T. A. (1989) A humanized antibody that binds to the interleukin 2 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 10029–10033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tan P., Mitchell D. A., Buss T. N., Holmes M. A., Anasetti C., Foote J. (2002) “Superhumanized” antibodies. Reduction of immunogenic potetial by complementarity-determining region grafting with human germline sequence. Application to an anti-CD28. J. Immunol. 169, 1119–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lazar G. A., Desjarlais J. R., Jacinto J., Karki S., Hammond P. W. (2007) A molecular immunology approach to antibody humanization and functional optimization. Mol. Immunol. 44, 1986–1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baca M., Presta L. G., O'Connor S. J., Wells J. A. (1997) Antibody humanization using phage display. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 10678–10684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gram H., Marconi L.-A., Barbas C. F., 3rd, Collet T. A., Lerner R. A., Kang A. S. (1992) In vitro selection and affinity maturation of antibodies from a naïve combinatorial immunoglobulin library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 3576–3580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawkins R. E., Russell S. J., Winter G. (1992) Selection of phage antibodies by binding affinity. Mimicking affinity maturation. J. Mol. Biol. 226, 889–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang W. P., Green K., Pinz-Sweeney S., Briones A. T., Burton D. R., Barbas C. F., 3rd (1995) CDR walking mutagenesis for the affinity maturation of a potent human anti-HIV-1 antibody into the picomolar range. J. Mol. Biol. 254, 392–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ho M., Kreitman R. J., Onda M., Pastan I. (2005) In vitro antibody evolution targeting germline hot spots to increase activity of an anti-CD22 immunotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 607–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ho M., Nagata S., Pastan I. (2006) Isolation of anti-CD22 Fv with high affinity by Fv display on human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9637–9642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowers P. M., Horlick R. A., Neben T. Y., Toobian R. M., Tomlinson G. L., Dalton J. L., Jones H. A., Chen A., Altobell L., 3rd, Zhang X., Macomber J. L., Krapf I. P., Wu B. F., McConnell A., Chau B., Holland T., Berkebile A. D., Neben S. S., Boyle W. J., King D. J. (2011) Coupling mammalian cell surface display with somatic hypermutation for the discovery and maturation of human antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20455–20460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rogozin I. B., Diaz M. (2004) Cutting edge. DGYW/WRCH is a better predictor of mutability at G:C bases in Ig hypermuation than the widely accepted RGYW/WRCY motif and probably reflects a two-step activiation-induced cytidine deaminase-triggered process. J. Immunol. 172, 3382–3384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin A., Scharff M. (2002) Somatic hypermutation of the AID transgene in B and non-B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12304–12308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cumbers S. J., Williams G. T., Davies S. L., Grenfell R. L., Takeda S., Batista F. D., Sale J. E., Neuberger M. S. (2002) Generation and iterative affinity maturation of antibodies in vitro using hypermutating B-cell lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 1129–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng N. Y., Wilson K., Jared M., Wilson P. C. (2005) Intricate targeting of immunoglobulin somatic hypermutation maximizes the efficiency of affinity maturation. J. Exp. Med. 201, 1467–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van den Brulle J., Fischer M., Langmann T., Horn G., Waldmann T., Arnold S., Fuhrmann M., Schatz O., O'Connell T., O'Connell D., Auckenthaler A., Schwer H. (2008) A novel solid phase technology for high-throughput gene synthesis. BioTechniques 45, 340–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu T. T., Kabat E. A. (1970) An analysis of the sequences of the variable regions of Bence Jones proteins and myeloma light chains and their implications for antibody complementarity. J. Exp. Med. 132, 211–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lefranc M.-P. (2004) IMGT-ONTOLOGY and IMGT databases, tools and web resources for immunogenetics and immunoinformatics. Mol. Immunol. 40, 647–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rogers J., Choi E., Souza L., Carter C., Word C., Kuehl M., Eisenberg D., Wall R. (1981) Gene segments encoding transmembrane carboxyl termini of immunoglobulin gamma chains. Cell 26, 19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greene L. A., Tischler A. S. (1976) Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenalpheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 73, 2424–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cattaneo A., Rapposelli B., Calissano P. (1988) Three distinct types of monoclonal antibodies after long-term immunization of rats with mouse nerve growth factor. J. Neurochem. 50, 1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chao G., Lau W. L., Hackel B. J., Sazinsky S. L., Lippow S. M., Wittrup K. D. (2006) Isolating and engineering human antibodies using yeast surface display. Nat. Protoc. 1, 755–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azoitei M. L., Correia B. E., Ban Y. E., Carrico C., Kalyuzhniy O., Chen L., Schroeter A., Huang P. S., McLellan J. S., Kwong P. D., Baker D., Strong R. K., Schief W. R. (2011) Computation-guided backbone grafting of a discontinuous motif onto a protein scaffold. Science 334, 373–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Azoitei M. L., Ban Y. E., Julien J. P., Bryson S., Schroeter A., Kalyuzhniy O., Porter J. R., Adachi Y., Baker D., Pai E. F., Schief W. R. (2012) Computational design of high-affinity epitope scaffolds by backbone grafting of a linear epitope. J. Mol. Biol. 415, 175–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fleishman S. J., Whitehead T. A., Ekiert D. C., Dreyfus C., Corn J. E., Strauch E. M., Wilson I. A., Baker D. (2011) Computational design of proteins targeting the conserved stem region of influenza hemagglutinin. Science 332, 816–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cattaneo A., Covaceuszach S., Lamba. D. (2005) Method for the humanization of antibodies and humanized antibodies thereby obtained. U. S. Patent WO/2005/061540

- 30. McConnell A. D., Do M., Neben T. Y., Spasojevic V., MacLaren J., Chen A. P., Altobell L., 3rd, Macomber J. L., Berkebile A. D., Horlick R. A., Bowers P. M., King D. J. (2012) Generation of high affinity humanized antibodies without making hybridomas. Immunization paired with mammalian cell display and in vitro somatic hypermutation. PLoS One 7, e49458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoet R. M., Cohen E. H., Kent R. B., Rookey K., Schoonbroodt S., Hogan S., Rem L., Frans N., Daukandt M., Pieters H., van Hegelsom R., Neer N. C., Nastri H. G., Rondon I. J., Leeds J. A., Hufton S. E., Huang L., Kashin I., Devlin M., Kuang G., Steukers M., Viswanathan M., Nixon A. E., Sexton D. J., Hoogenboom H. R., Ladner R. C., (2005) Generation of high-affinity human antibodies by combining donor-derived and synthetic complementarity-determining-region diversity. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 344–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chowdhury P. S., Pastan I. (1999) Improving antibody affinity by mimicking somatic hypermutation in vitro. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 568–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Covaceuszach S., Cassetta A., Konarev P. V., Gonfloni S., Rudolph R., Svergun D. I., Lamba D., Cattaneo A. (2008) Dissecting hβNGF interactions with TrkA and p75 receptors by structural and functional studies of an anti-NGF neutralizing antibody. J. Mol. Biol. 381, 881–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]