Background: Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) forms a homodimer that metabolizes a neuroprotective class of lipids termed epoxyeicosatrienoic acids.

Results: Mutations on the dimerization interface of sEH eliminate hydrolase enzymatic activity.

Conclusion: Dimerization is required for sEH enzymatic activity.

Significance: Dimerization is a novel target for sEH inhibition.

Keywords: Eicosanoid, Eicosanoid-specific Enzymes, Eicosanoid-specific Genes, Ischemia, Protein Structure, Dimerization, Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids, Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase

Abstract

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) plays a key role in the metabolic conversion of the protective eicosanoid 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid to 14,15-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid. Accordingly, inhibition of sEH hydrolase activity has been shown to be beneficial in multiple models of cardiovascular diseases, thus identifying sEH as a valuable therapeutic target. Recently, a common human polymorphism (R287Q) was identified that reduces sEH hydrolase activity and is localized to the dimerization interface of the protein, suggesting a relationship between sEH dimerization and activity. To directly test the hypothesis that dimerization is essential for the proper function of sEH, we generated mutations within the sEH protein that would either disrupt or stabilize dimerization. We quantified the dimerization state of each mutant using a split firefly luciferase protein fragment-assisted complementation system. The hydrolase activity of each mutant was determined using a fluorescence-based substrate conversion assay. We found that mutations that disrupted dimerization also eliminated hydrolase enzymatic activity. In contrast, a mutation that stabilized dimerization restored hydrolase activity. Finally, we investigated the kinetics of sEH dimerization and found that the human R287Q polymorphism was metastable and capable of swapping dimer partners faster than the WT enzyme. These results indicate that dimerization is required for sEH hydrolase activity. Disrupting sEH dimerization may therefore serve as a novel therapeutic strategy for reducing sEH hydrolase activity.

Introduction

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH)2 forms a domain-swapped dimer in which the hydrolase domain of one monomer binds to the phosphatase domain of the opposite monomer (1, 2). Although sEH exhibits two enzymatic activities, it is the hydrolase activity, which converts the protective eicosanoid 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid to its vicinal diol 14,15-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid, that is most understood (3). Inhibition of sEH hydrolase activity by either pharmacological tools or gene deletion has been shown to be protective in multiple models of cardiovascular diseases, thus identifying sEH as a valuable therapeutic target (4, 5). Additionally, multiple human missense polymorphisms have been identified throughout the structure of the protein that alter the hydrolase enzymatic activity of sEH (6). Specifically, a human R287Q polymorphism has been shown in vitro to decrease the hydrolase activity (6). Surprisingly, Arg-287 is not located near the hydrolase catalytic site, suggesting that its effect on the enzyme cannot be explained by a simple perturbation of the active site fold or by interference with substrate binding. Based on the crystal structure of sEH (7), Arg-287 is localized near the center of the enzyme on the dimerization interface (6). This suggests that the effect of this polymorphism may be functionally linked to its effect on dimerization. Further supporting a critical role for this residue in the stabilization of sEH dimerization is its close proximity (within 4 Å) to Glu-254 on the opposing monomer, where it may be forming an intermonomeric salt bridge (6, 8). Indeed, it has been shown previously that sEH protein harboring the R287Q polymorphism forms increased amounts of monomer compared with the wild-type protein (8). We set out to directly test the hypothesis that sEH dimerization is required for hydrolase activity using mutational analysis. We mutated the residues in the putative Glu-254–Arg-287 dimer-stabilizing salt bridge to either disrupt or stabilize sEH dimerization. We established a split firefly luciferase protein fragment-assisted complementation (SFL-PFAC) system to validate sEH dimerization and measured sEH hydrolase activity with a fluorescent substrate of sEH (9–11). Understanding the mechanism by which the R287Q polymorphism (HapMap frequency between 0.08 and 0.24) affects the sEH enzyme is highly clinically relevant and may shed light on the pleiotropic clinical manifestations of this polymorphism (12–15). Additionally, this research supports the development of novel therapeutic strategies for inhibiting sEH hydrolase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutagenesis of sEH Salt Bridge Residues

Mutagenesis of sEH was performed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mutagenic primers to create the R287E and E254R mutations were designed with the QuikChange primer design program (Stratagene). Briefly, 100 ng of wild-type sEH template and 100 ng of each mutagenic primer were used in the reaction with a total reaction volume of 25 μl. After 30 cycles of PCR amplification of DNA template, 1 μl of DpnI restriction enzyme was added to 10 μl of each amplification reaction and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. 1.5 μl of the DpnI-treated DNA from each mutagenesis reaction was used to transform XL10-Gold ultracompetent cells. The DNA was purified using a Qiagen purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Creation of sEH-Luciferase Constructs

The C- and N-terminal split firefly fragments were described previously (11). Human sEH was amplified with PCR using primers that added a 3′-NheI site and a 5′-SacI site and ligated into the split firefly luciferase vectors. All constructs were verified by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing.

Transfection

HEK cells were either singly transfected or cotransfected according to the manufacturer's recommendations with different expression plasmids premixed with LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen) and cultured overnight in Opti-MEM medium.

Luciferase Activity Assay

Transfected HEK cells were lysed with Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). The luminometer assays for firefly luciferase activity were performed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The luciferase activity was measured using a Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (Berthold Technologies).

Hydrolase Activity Assay

sEH hydrolase activity was determined using Epoxy Fluor 7 (Cayman Chemical Co.). Cells were lysed in Passive Lysis Buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture on ice before immediate quantification of hydrolase activity. Hydrolase activity was assessed as described previously (9). Briefly, reactions were carried out in 200 μl of 25 mm BisTris-HCl containing 1 mg/ml BSA and the substrate Epoxy Fluor 7. The resulting solution was incubated at 37 °C in a black 96-well flat bottom plate (Corning). The fluorescence of hydrolyzed Epoxy Fluor 7 was determined using an excitation wavelength of 330 nm (bandwidth of 20 nm) and an emission wavelength of 465 nm (bandwidth of 20 nm) on a VICTOR plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Determination of Km and Vmax

The Km and Vmax of sEH constructs were determined using the following concentrations of Epoxy Fluor 7: 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 20, and 40 μm. 10 μl of crude cell lysates from each transfection was used in each reaction, and the amount of Me2SO was kept constant at 1.6%. Data were collected from three independently transfected cultures in duplicate. Substrate concentration was plotted against initial velocities for each construct to derive Km and Vmax using GraphPad Prism 5.

Protein Rendering

PyMOL (Delano Scientific LLC) was used for protein modeling. The crystal structure for mouse sEH (Protein Data Bank code 1CR6) (7) was used for modeling the sEH salt bridge because it was crystallized as a dimer. Arg-287 and Glu-254 in the human enzyme are homologous to Arg-285 and Glu-252 in the mouse enzyme.

Immunoblotting

Transfected HEK cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE (90 min, 200 V) and transferred to Amersham Biosciences Hybond-LFP membranes (GE Healthcare) at 35 V for 2 h. After blocking with 3% ECL advanced blocking agent (GE Healthcare) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween X-100, sEH-luciferase constructs were detected with HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody (1:1000; Sigma). The antibody was incubated on a membrane for 2 h at room temperature before being washed out three times with PBS/Tween. Chemiluminescence was then detected using SuperSignal West Dura extended duration substrate (Thermo Scientific) with a FluorChem FC2 imager (Alpha Innotech). Densitometry was quantified using AlphaView software (Alpha Innotech).

Statistics

For multiple group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis. For dimerization time course studies, repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was performed with one factor being time and the other being mutation status, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis.

RESULTS

Generation of sEH Dimerization Mutants

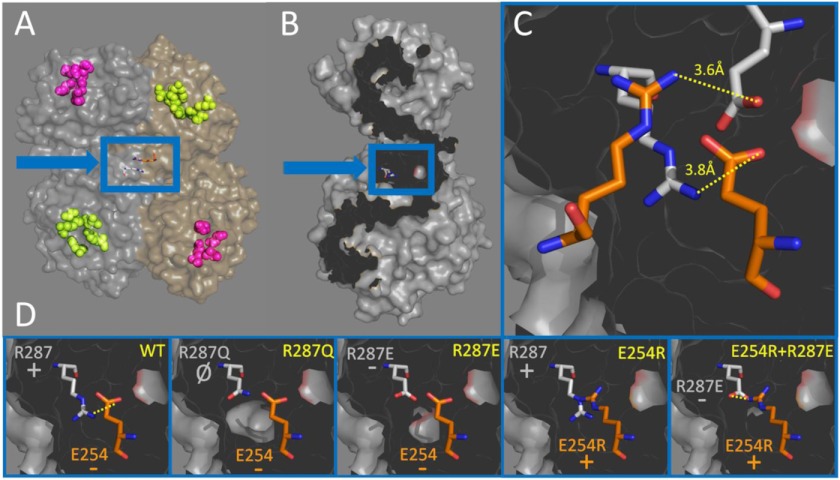

Based on the dimer structure of sEH, Arg-287 is located in the center of the protein (Fig. 1A) and on the dimerization interface (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, Arg-287 is localized in close proximity to Glu-254 of the opposing monomer, which would form a putative dimer-stabilizing salt bridge (Fig. 1C). Two salt bridge pairs, Arg-287–Glu-254 and Glu-254–Arg-287, are presumed to form. These residues are 3.6 and 3.8 Å apart from each other, within the typical distance range for a stabilizing salt bridge (16). To generate mutants of sEH that would either disrupt or stabilize dimerization, we performed mutational analysis on this putative Glu-254–Arg-287 salt bridge (Fig. 1D). First, we mutated Arg-287 to glutamate (R287E), thereby placing two negatively charged residues opposite each other. On the basis of the previous observation that the human polymorphism (R287Q) only partially disrupted sEH dimerization (6), we hypothesized that our more severe mutation would completely abolish dimerization. Additionally, we generated another mutant of sEH, which we hypothesized would also abolish dimerization, by changing Glu-254 to arginine (E254R), thus placing two positively charged amino acids opposite each other. Finally, we combined both the R287E and E254R mutations, which may rescue sEH dimerization by re-forming the dimer-stabilizing salt bridges, but in the reverse orientation of the WT enzyme.

FIGURE 1.

sEH dimerization architecture, dimer-stabilizing salt bridge, and dimerization mutations. A, one monomeric subunit of sEH (tan) binds to another monomeric subunit (gray) of sEH. Arg-287 (blue arrow and box) is located away from the hydrolase-active site (yellow) and phosphatase-active site (purple). B, Arg-287 (blue arrow and box) is localized on the dimerization interface of sEH (dark gray). C, two salt bridge pairs are formed between Glu-254 and Arg-287 in the dimer structure, which are 3.6 and 3.8 Å apart. Residues from one sEH monomeric subunit are gray, whereas residues from the opposite monomeric subunit are orange. D, diagram of how one salt bridge pair changes with the WT, R287Q, R287E, E254R, and E254R/R287E constructs. The construct name is in yellow, whereas the residue and the charge of the amino acid are in either gray or orange depending on which monomeric subunit they are from.

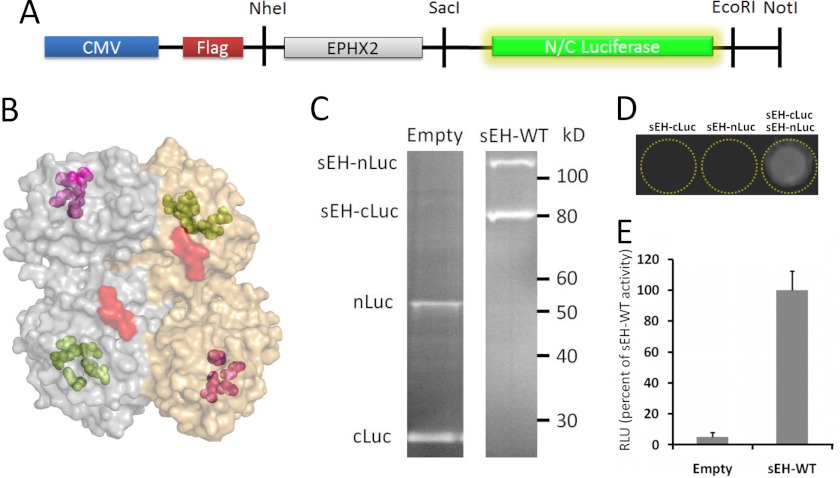

Split Luciferase System as a Reporter Assay for sEH Dimerization

To simultaneously measure sEH dimerization and hydrolase activity, we employed a SFL-PFAC strategy (10–11). Firefly luciferase can be split into a C-terminal (referred to below as cLuc) and an N-terminal (nLuc) fragment, which are catalytically inactive separately. However, luciferase activity can be restored if two binding proteins can bring the luciferase fragments together. We used this system to monitor sEH homodimerization by attaching the split firefly luciferase fragments to the C terminus of sEH separated by a short glycine/serine-rich linker (Fig. 2, A–C). Despite domain-swapped dimer orientation, the C termini of sEH are in close proximity to each other, which facilitates efficient complementation of luciferase fragments (Fig. 2B). Next, we cotransfected sEH-nLuc and sEH-cLuc into HEK cells. Consistent with our hypothesis, the individual N- and C-terminal luciferase fusions were devoid of any activity by themselves (Fig. 2D). Coexpression of sEH-nLuc and sEH-cLuc in HEK cells resulted in a robust increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 2E, sEH-WT) compared with expression of luciferase termini unattached to sEH (referred to below as EM) (Fig. 2E, Empty), establishing SFL-PFAC as a reporter assay for measuring sEH dimerization.

FIGURE 2.

Split firefly luciferase measures sEH dimerization. A, schematic representation of the sEH-luciferase-expressing plasmid. EPHX2 is the gene name for sEH. B, orientation and proximity of the C-terminal ends (red) of the sEH dimer to which luciferase fragments were attached. C, Western blots of HEK cell lysates cotransfected with split firefly luciferase constructs either unattached (Empty) or attached to sEH (sEH-WT). D, charge-coupled device exposure of HEK cell lysates producing light when cotransfected with WT sEH, but not when singly transfected. E, compared with lysates expressing the two termini of luciferase alone, attaching sEH increased the luciferase activity. Data represent means ± S.E. RLU, relative light units.

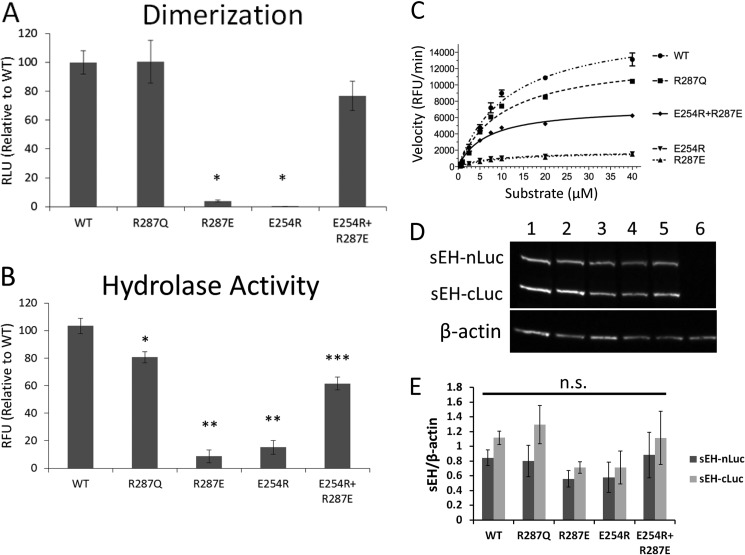

Dimerization Is Required for sEH Hydrolase Enzymatic Activity

To test our hypothesis that dimerization is required for hydrolase activity, we subcloned WT and mutant (R287E, E254R, and E254R/R287E) sEH cDNAs in frame with the N or C terminus of firefly luciferase. We transfected HEK cells overnight using Lipofectamine 2000 and then lysed the cells to perform a luciferase assay to quantify dimerization and a hydrolase assay to quantify enzymatic activity. We found that both the R287E and E254R mutations abolished the dimer formation as evidenced by loss of luciferase activity (p < 0.05 compared with WT sEH) (Fig. 3A). Importantly, these two mutations also inactivated hydrolase enzymatic activity (p < 0.05 compared with WT sEH) (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, the double mutant E254R/R287E restored both dimerization and hydrolase activity (p < 0.05 compared with E254R and R287E for both luciferase and hydrolase activities). Surprisingly, although the R287Q mutant did not have a significantly different luciferase activity compared with WT sEH, it did show a decrease in hydrolase activity (p < 0.05 compared with WT sEH), consistent with what has been previously reported (6). Additionally, we determined the Km and relative Vmax of each of the sEH constructs (Fig. 3C). We found that the decrease in enzymatic activity caused by disrupting dimerization was the result of decreasing the Vmax of the enzyme rather than increasing the Km (Table 1). Specifically, the dimerization-impaired mutants R287E and E254R had only 8.5 and 7.8% of the relative Vmax of WT sEH, respectively, whereas the dimerization-stabilizing mutation R254R/R287E increased the relative Vmax to 36.9% of WT sEH. To confirm that the differences between luciferase and hydrolase activities in these mutants were not due to differences in transfection efficiencies, we quantified expression of sEH constructs by Western blotting, which showed no significant differences in levels of expression (Fig. 3, D and E).

FIGURE 3.

Luciferase and hydrolase activities of sEH dimerization mutants. A, luciferase activity of lysate from HEK cells transfected with sEH dimerization mutants relative to WT sEH (n = seven independently transfected cultures). Data represent means ± S.E. RLU, relative light units. *, p < 0.05 compared with WT, R287Q, and E254R/R287E proteins by one-way ANOVA. B, hydrolase activity of lysate from HEK cells transfected with sEH dimerization mutants relative to WT sEH (n = seven independently transfected cultures). Data represent means ± S.E. RFU, relative fluorescent units. *, p < 0.05 compared with WT, R287E, E254R, and E254R/R287E proteins; **, p < 0.05 compared with WT, R287Q, and E254R/R287E proteins; ***, p < 0.05 compared with WT, R287Q, E254R, and R287E proteins by one-way ANOVA. C, plot of the velocity of hydrolase activity at various substrate concentrations of Epoxy Fluor 7. Data represent means ± S.E. of a representative experiment. D, immunoblot of sEH-luciferase constructs transfected into HEK cells. Lane 1, WT sEH; lane 2, R287Q; lane 3, R287E; lane 4, E254R; lane 5, E254R/R287E; lane 6, not transfected. E, quantification of sEH-luciferase Western blots (n = three independently transfected cultures for WT sEH and four independently transfected cultures for all other constructs). Data represent means ± S.E. n.s., not significant by one-way ANOVA.

TABLE 1.

Hydrolase activity kinetic constants

Shown are the Km and relative Vmax of hydrolase enzymatic activity with Epoxy Fluor 7 substrate. Values were determined from three independently transfected cultures with readings in duplicate.

| Km | Relative Vmax | |

|---|---|---|

| μm | ||

| WT | 15.08 ± 2.70 | 100.0 ± 13.1 |

| R287Q | 10.17 ± 0.65 | 61.4 ± 5.5 |

| R287E | 6.96 ± 1.52 | 8.5 ± 0.5 |

| E254R | 5.84 ± 1.10 | 7.8 ± 0.9 |

| E254R/R287E | 6.91 ± 0.68 | 36.9 ± 0.6 |

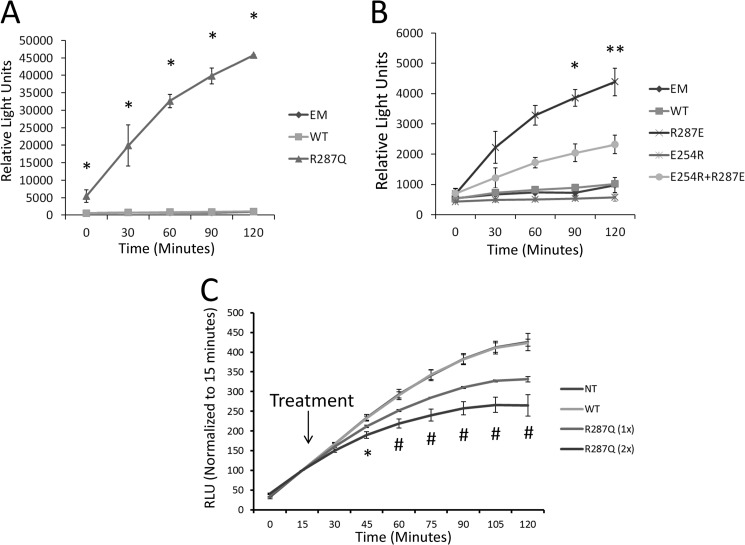

Kinetics of sEH Dimerization

We performed kinetic analysis to examine the rate of sEH dimerization. To do this, we transfected HEK cells with individual sEH constructs attached to either terminus of luciferase, extracted the protein, and mixed the lysates together before measuring luciferase activity every 30 min for 2 h. Interestingly, we found that mixed lysates from the R287Q mutation of sEH had significantly enhanced luciferase activity compared with the WT enzyme (>4000% of WT sEH at 2 h) or the two ends of luciferase unattached to sEH (>4000% of EM at 2 h) (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the WT enzyme showed no increase in luciferase activity over the 2-h period compared with the unattached luciferase termini (104% of EM at 2 h). We interpreted this to mean that the dimer formed between the WT monomers is so strong that it will not break apart to form new dimers to result in luciferase activity. On the other hand, the R287Q mutation causes a metastable dimer such that sEH protein harboring the R287Q mutation is able to break apart and form a new dimer with another partner. Mixing lysates from the other dimerization constructs showed that the R287E constructs had slightly higher luciferase activity than all constructs except for R287Q (400% of EM at 2 h) (Fig. 4B). To validate that the WT protein dimer is sufficiently strong that it is unable to break apart and form a new dimer, we performed a competition study. We mixed lysates from R287Q in a similar manner as described for Fig. 4A, except that, at 15 min, we added lysates from either untransfected HEK cells or cells transfected with WT or R287Q sEH protein, which was not attached to a terminus of luciferase. We hypothesized that adding R287Q unattached to luciferase would decrease luciferase activity by forming luciferase-inactive sEH-Luc/sEH dimers; however, adding the WT protein would not decrease dimerization because the WT protein would not be able to break apart to form any sEH-Luc/sEH dimers. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that adding only the R287Q protein decreased the luciferase signal compared with adding lysate from untransfected cells (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, we found that the amount of R287Q protein we added (1× versus 2×) directly correlated with the amount of luciferase inhibition. This finding further validates the specificity of the SFL-PFAC assay for measuring sEH dimerization.

FIGURE 4.

Kinetics of dimer formation in sEH. A, luciferase activity of mixed lysates from HEK cells transfected with sEH dimerization constructs attached to a single terminus of luciferase or domains unattached to sEH (EM) (n = three independent mixes). Data represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 compared with EM and WT sEH by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. B, luciferase activity from mixed lysates of HEK cells transfected with sEH dimerization constructs attached to a single terminus of luciferase (n = three independent mixes). Data represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 compared with EM, WT, and E254R proteins; **, p < 0.05 compared with EM, WT, E254R, and E254R/R287E proteins by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. C, R287Q mixed lysate treated at 15 min with lysates from HEK cells not transfected (NT) or transfected with non-luciferase-tagged WT or R287Q protein at either a low dose (1×) or a high dose (2×) (n = three independent mixes). RLU, relative light units. Data were normalized to the value immediately before treatment at 15 min. Data represent means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 for NT and WT compared with R287Q(2×); #, p < 0.05 for NT and WT compared with R287Q(1×) and R287Q(2×) as well as R287Q(1×) compared with R287Q(2×) by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

sEH in its native form is a domain-swapped homodimer. We investigated if dimerization is required for its hydrolase enzymatic activity. Specifically, we used mutational analysis of a putative intermonomeric salt bridge to manipulate the dimerization state of the enzyme. We found that the Glu-254–Arg-287 salt bridge interaction is essential for dimerization as well as activity. By disrupting dimerization with either the R287E or E254R mutation, we abolished both dimerization and hydrolase activity. However, by combining the two mutations (E254R/R287E), we reversed the salt bridge and rescued both sEH dimerization and activity. We interpreted these results to mean that sEH dimerization is required for hydrolase activity.

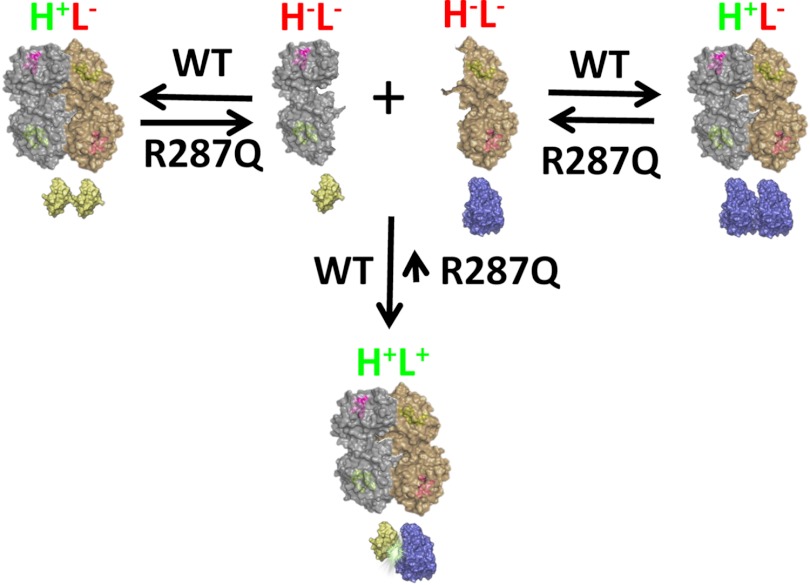

We were surprised to find that the human R287Q polymorphism did not show a decrease in luciferase activity while still having lower hydrolase activity compared with the WT enzyme. On the basis of published reports (6–8), we expected to see a decrease in both activities. One likely explanation for this unexpected result is that the complemented split luciferase fragments somehow artificially stabilize the metastable R287Q protein. Therefore, the luciferase-active and hydrolase-active heterodimer (Fig. 5, H+L+) is preferentially formed over the luciferase-inactive homodimers (Fig. 5, H+L−) at equilibrium. Other bimolecular fluorescence complementation systems have previously been shown to artificially increase the stability of protein-protein interactions (17); however, protein fragments that form covalent chromophores when complemented such as in split YFP were used. We intentionally chose a split firefly luciferase system because the system is reversible and thus less likely to artificially stabilize the dimer (18). Nevertheless, the data in Fig. 3 suggest this possibility with the R287Q protein. To our knowledge, this is the first instance of artificial stabilization of a protein using a split firefly luciferase system and is probably due to the fact that the R287Q mutation causes a metastable protein. The R287Q protein is the only metastable construct (Fig. 4, A and B), and thus, the luciferase activity is increased only with this protein. Additionally, based on the experiments in Fig. 4C, the stabilization caused by luciferase fragments is secondary to the actual sEH protein homodimerization because proteins without luciferase fragments are able to competitively bind the sEH-luciferase construct, thus suppressing luciferase activity. This leads us to conclude that the luciferase activity is accurately reflecting the dimerization state for WT, R287E, E254R, and E254R/R287E proteins.

FIGURE 5.

Model of sEH-luciferase dimerization. Cells transfected with sEH form three populations of dimers: sEH-cLuc/sEH-nLuc, which are hydrolase- and luciferase-active (H+L+), and sEH-cLuc/sEH-cLuc and sEH-nLuc/sEH-nLuc, which are hydrolase-active but luciferase-inactive (H+L−). In the WT protein, these three populations are static because the Glu-254–Arg-287 salt bridge bond stabilizes the dimer. In contrast, the R287Q polymorphism disrupts dimerization such that the equilibrium shifts toward hydrolase- and luciferase-inactive monomers (H−L−). However, the complemented luciferase fragments stabilize the metastable R287Q dimer, resulting in similar levels of luciferase activity compared with the WT enzyme. One sEH monomer is colored gray, whereas the other is colored tan. The C terminus of luciferase is colored yellow, and the N terminus is colored blue.

We also measured the kinetics of sEH homodimerization. Interestingly, we found that sEH harboring the human R287Q polymorphism rapidly formed new dimer pairs, whereas the WT enzyme remained static, indicating that the Glu-254–Arg-287 interaction is strong enough to hold the dimerization state. This result may explain why previous studies have detected hydrolase enzymatic activity of the monomer fraction of sEH (7). Although it would be possible to separate sEH monomers from dimers, once the monomers are separated, they would rapidly form enzymatically active dimers while the activity was being measured.

It has been speculated that Glu-254–Arg-287 may form an intramonomeric salt bridge rather than an intermonomeric salt bridge (6). Analysis of the sEH crystal structure using ESBRI (19) yields intermonomeric salt bridges between Glu-254 and Arg-287. Indeed, our results argue that they form an intermonomeric salt bridge because of their critical role in stabilizing sEH dimerization. It might also be argued that the dimer-disrupting mutations may be affecting the stability of the protein; however, this is unlikely because introducing double mutations results in the rescue of both dimerization and hydrolase activity.

sEH is a bifunctional enzyme with hydrolase and phosphatase catalytic activities (1, 2). Although we addressed the hypothesis that sEH dimerization is required for hydrolase activity, one limitation of our study is that we did not examine the effect of dimerization on phosphatase activity. Such studies are limited, however, by the availability of sEH-specific phosphatase substrates. Nevertheless, the effect of dimerization on phosphatase enzymatic activity remains an interesting and important question, which should be addressed in future studies as new research tools become available and as new roles for the phosphatase domain in the biology of sEH emerge.

sEH plays a role in the development and outcome of multiple cardiovascular diseases through its role in the metabolism of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (20). Understanding sEH biology is therefore highly clinically relevant. The investigation of the dimerization kinetics of a common human polymorphism of sEH, R287Q, also has important clinical implications. Based on the finding that the human R287Q polymorphism is metastable, the clinical effects linked to this human polymorphism must be viewed in light of its effect on sEH dimerization, in addition to its effect on hydrolase enzymatic activity (12–15). We speculate that disrupting dimerization may represent a novel means by which sEH hydrolase activity can be regulated within the cells. However, further work is required to understand how dimerization may be an endogenous regulator of sEH function. Finally, the data presented here suggest that disrupting sEH dimerization may serve as a novel therapeutic approach to inhibiting sEH enzymatic activity. The split firefly luciferase system described here may provide the framework for creating a high-throughput sEH dimerization drug screen.

In conclusion, we found that sEH hydrolase activity is dependent on sEH dimerization. We developed a novel technique for monitoring the effect that sEH mutations have on dimerization and established a model system for controlling the dimerization status of sEH that can be used in future experiments to monitor the effect of sEH dimerization on other aspects of sEH biology.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dominic Siler for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NS44313 (to N. J. A.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 11PRE5710008 (to J. W. N.).

- sEH

- soluble epoxide hydrolase

- SFL-PFAC

- split firefly luciferase protein fragment-assisted complementation

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- ANOVA

- one-way analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Newman J. W., Morisseau C., Harris T. R., Hammock B. D. (2003) The soluble epoxide hydrolase encoded by EPXH2 is a bifunctional enzyme with novel lipid phosphate phosphatase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1558–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cronin A., Mowbray S., Dürk H., Homburg S., Fleming I., Fisslthaler B., Oesch F., Arand M. (2003) The N-terminal domain of mammalian soluble epoxide hydrolase is a phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1552–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iliff J. J., Alkayed N. J. (2009) Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition: targeting multiple mechanisms of ischemic brain injury with a single agent. Future Neurol. 4, 179–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang W., Otsuka T., Sugo N., Ardeshiri A., Alhadid Y. K., Iliff J. J., DeBarber A. E., Koop D. R., Alkayed N. J. (2008) Soluble epoxide hydrolase gene deletion is protective against experimental cerebral ischemia. Stroke 39, 2073–2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang W., Koerner I. P., Noppens R., Grafe M., Tsai H. J., Morisseau C., Luria A., Hammock B. D., Falck J. R., Alkayed N. J. (2007) Soluble epoxide hydrolase: a novel therapeutic target in stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 1931–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Przybyla-Zawislak B. D., Srivastava P. K., Vazquez-Matias J., Mohrenweiser H. W., Maxwell J. E., Hammock B. D., Bradbury J. A., Enayetallah A. E., Zeldin D. C., Grant D. F. (2003) Polymorphisms in human soluble epoxide hydrolase. Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 482–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Argiriadi M. A., Morisseau C., Hammock B. D., Christianson D. W. (1999) Detoxification of environmental mutagens and carcinogens: structure, mechanism, and evolution of liver epoxide hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10637–10642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Srivastava P. K., Sharma V. K., Kalonia D. S., Grant D. F. (2004) Polymorphisms in human soluble epoxide hydrolase: effects on enzyme activity, enzyme stability, and quaternary structure. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 427, 164–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jones P. D., Wolf N. M., Morisseau C., Whetstone P., Hock B., Hammock B. D. (2005) Fluorescent substrates for soluble epoxide hydrolase and application to inhibition studies. Anal. Biochem. 343, 66–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiang Y., Bernard D., Yu Y., Xie Y., Zhang T., Li Y., Burnett J. P., Fu X., Wang S., Sun D. (2010) Split Renilla luciferase protein fragment-assisted complementation (SRL-PFAC) to characterize Hsp90-Cdc37 complex and identify critical residues in protein/protein interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21023–21036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luker K. E., Smith M. C. P., Luker G. D., Gammon S. T., Piwnica-Worms H., Piwnica-Worms D. (2004) Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12288–12293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohtoshi K., Kaneto H., Node K., Nakamura Y., Shiraiwa T., Matsuhisa M., Yamasaki Y. (2005) Association of soluble epoxide hydrolase gene polymorphism with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 347–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burdon K. P., Lehtinen A. B., Langefeld C. D., Carr J. J., Rich S. S., Freedman B. I., Herrington D., Bowden D. W. (2008) Genetic analysis of the soluble epoxide hydrolase gene, EPHX2, in subclinical cardiovascular disease in the Diabetes Heart Study. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 5, 128–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang L., Ding H., Yan J., Hui R., Wang W., Kissling G. E., Zeldin D. C., Wang D. W. (2008) Genetic variation in cytochrome P450 2J2 and soluble epoxide hydrolase and risk of ischemic stroke in a Chinese population. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 18, 45–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee C. R., Pretorius M., Schuck R. N., Burch L. H., Bartlett J., Williams S. M., Zeldin D. C., Brown N. J. (2011) Genetic variation in soluble epoxide hydrolase (EPHX2) is associated with forearm vasodilator responses in humans. Hypertension 57, 116–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumar S., Nussinov R. (2002) Relationship between ion pair geometries and electrostatic strengths in proteins. Biophys. J. 83, 1595–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu C. D., Chinenov Y., Kerppola T. K. (2002) Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol. Cell 9, 789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jester B. W., Cox K. J., Gaj A., Shomin C. D., Porter J. R., Ghosh I. (2010) A coiled-coil enabled split-luciferase three-hybrid system: applied toward profiling inhibitors of protein kinases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11727–11735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Costantini S., Colonna G., Facchiano A. M. (2008) ESBRI: a web server for evaluating salt bridges in proteins. Bioinformation 3, 137–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imig J. D., Hammock B. D. (2009) Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 794–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]