Background: Regulation of p73 by HDAC inhibitor or individual HDAC has not been elucidated.

Results: HDAC1 inhibition inactivates Hsp90 and disrupts its binding to TAp73, thereby targeting p73 for proteasomal degradation.

Conclusion: HDAC1 is a critical regulator of TAp73 protein stability.

Significance: Our data shed a light on a novel regulation of TAp73 protein stability by HDAC1-Hsp90 chaperone complex.

Keywords: Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors, Hsp90, p53, p73, Protein Stability, HDAC1, The p53 Family

Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) play important roles in fundamental cellular processes, and HDAC inhibitors are emerging as promising cancer therapeutics. p73, a member of the p53 family, plays a critical role in tumor suppression and neural development. Interestingly, p73 produces two classes of proteins with opposing functions: the full-length TAp73 and the N-terminally truncated ΔNp73. In the current study, we sought to characterize the potential regulation of p73 by HDACs and found that histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) is a key regulator of TAp73 protein stability. Specifically, we showed that HDAC1 inhibition by HDAC inhibitors or by siRNA shortened the half-life of TAp73 protein and subsequently decreased TAp73 expression under normal and DNA damage-induced conditions. Mechanistically, we found that HDAC1 knockdown resulted in hyperacetylation and inactivation of heat shock protein 90, which disrupted the interaction between heat shock protein 90 and TAp73 and thus promoted the proteasomal degradation of TAp73. Functionally, we found that down-regulation of TAp73 was required for the enhanced cell migration mediated by HDAC1 knockdown. Together, we uncover a novel regulation of TAp73 protein stability by HDAC1-heat shock protein 90 chaperone complex, and our data suggest that TAp73 is a critical downstream mediator of HDAC1-regulated cell migration.

Introduction

p73, along with p53 and p63, constitutes the p53 family. These proteins share a significant degree of sequence homology, especially in the DNA-binding domain, and play a critical role in regulating cell cycle, apoptosis, and differentiation (1). Like p53 and p63, p73 is expressed as multiple isoforms. At the C terminus, the p73 gene expresses at least seven different isoforms (α, β, γ, δ, ϵ, ζ, and η) because of alternative splicing (2). In addition, at the N terminus, because of the usage of two different promoters, p73 produces different isoforms, the full-length TAp73 and the N-terminally truncated ΔNp73. The TAp73 isoform is transcribed from the upstream promoter and contains an N-terminal activation domain with homology to that in p53, whereas the ΔNp73 isoforms are transcribed from the downstream promoter in intron 3 and N-terminally truncated. Consequently, the TAp73 isoforms contain many p53-like properties, such as transactivation of a subset of p53 target genes necessary for induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (1, 3). By contrast, the ΔNp73 isoforms are thought to act as an oncogene against the full-length TAp73 as well as p53 (4–6). Interestingly, in some settings, ΔNp73 retains transcriptional activities (7–9). The biological function of p73 has been implicated in neural development and tumor suppression. Indeed, p73-deficient (lacking both the TA and ΔN isoforms) mice exhibit abnormalities in neural development, such as hippocampal dysgenesis, hydrocephalus, loss of Cajal-Retzius neurons, and defects in pheromone sensory pathways (67). Similarly, mice deficient in ΔNp73 do not develop tumors but are prone to delayed onset of moderate neurodegeneration (10, 11). By contrast, mice deficient in TAp73 show an increased incidence of both spontaneous and 7,12-dimethylbenz[α]anthracene (DMBA)-induced tumors (12), as well as accelerated aging (13). The difference between TAp73 and ΔNp73 knock-out mice not only demonstrates that TAp73 is a bona fide tumor suppressor but also indirectly suggests that ΔNp73 has an oncogenic potential. Thus, the proper balance between TAp73 and ΔNp73 is important to maintain the genomic fidelity. Notably, TAp73 can be activated by many chemotherapeutic agents and induce p53-independent cell death (14, 15). Because p73 is rarely mutated in human cancers (16), therefore, activation of TAp73 represents an attractive strategy for cancer treatments, especially for those where p53 is inactivated.

Because of the critical role of p73 in tumor suppression and development, many studies have been carried out to determine how p73 expression is regulated. For example, in response to DNA damage, transcription factor E2F1 binds to the P1 promoter and up-regulates p73 mRNA (17–19). Interestingly, E2F1-induced p73 expression is also modulated by several other regulators, including transcriptional activator YY1 (Ying Yang 1) (20), transcriptional repressors ZEB1 (δEF1) and C-EBPα (21, 22), Chk1/2 protein kinases (23), and histone acetyltransferase P300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) (24, 25). Moreover, we showed recently that p73 mRNA can be stabilized by RNA-binding protein RNPC1 through a CU-rich element in its 3′-UTR (26). Furthermore, p73 proteins are subjected to post-translational modifications such as acetylation by acetyltransferase CBP/p300 (27) and phosphorylation by kinases including c-Abl (28–30), JNK (31), p38 (32), and PKCδ (33). Finally, p73 proteins can be targeted for ubiquitin-dependent and -independent proteasomal degradation by several E3 ligases, including the NEDD4-like ubiquitin ligase Itch (34), the F-box protein FBXO45 (35), the Ring finger domain ubiquitin ligases PIR2 and Pirh2 (36, 37), and the U-box type E3/E4 ubiquitin ligase UFD2a (38). These results suggest that p73 expression is regulated by complex molecular signaling pathways. Thus, identifying additional regulators of p73 will provide a better understanding of the p73 pathway and shed considerable light on how to manipulate the p73 pathway for cancer management.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs)2 are a family of enzymes that catalyze the removal of acetyl moieties from acetylated proteins including histones, structural proteins, or transcription factors (39). There are four classes of HDACs: class I (HDAC 1, 2, 3, 8), class II (HDAC 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10), class III (SIRT 1–7), and class IV (HDAC 11). HDACs in classes I, II, and IV contain a conserved catalytic domain and can be inhibited by HDAC inhibitors (HDACIs), such as trichostatin A and sodium butyrate. Class III HDACs contain a NAD-dependent catalytic domain and are insensitive to pan-HDACIs. Functionally, HDACs are involved in many diverse processes such as transcriptional regulation, protein-protein interaction, and protein subcellular localization. Notably, HDACs alterations are found in many human cancers (40). Thus, HDACIs, which have been shown to inhibit proliferation and to induce apoptosis, are emerging as a new promising class of anticancer drugs (41). For instance, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) (Vorinostat) is the first Food and Drug Administration-approved HDACI drug for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Currently, HDACIs are tested in many phase I, II, and III clinical trials as single agents, as well as in combination schemes. However, the efficacy of HDACIs in tumor suppression has come out with both encouraging and disappointing results. These mixed results are largely due to a lack of understanding regarding the molecular basis of HDACI-induced anti-cancer effect. Thus, further dissection of the mechanism(s) by which HDACIs modulate gene expression remains a subject of intense investigation.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the p53 family proteins are regulated by various HDACs through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. For example, HDAC1 deacetylates p53 and affect its transcriptional activity (42, 43), whereas HDAC2 modulates the ability of p53 to bind DNA and p53-dependent transcription (44). Additionally, p53 transcription is found to be regulated by HDAC8 via HoxA5, whereas the protein stability of mutant p53 is found to be regulated by HDAC6-Hsp90 chaperone (45, 46). Furthermore, ΔNp63 transcription is found to be regulated by HDAC2 via Dec1 (47). However, it remains unclear whether HDACs modulate p73 expression and activity. Thus, we investigated the potential cross-talk between TAp73 and HDACs and found that HDAC1 is a critical regulator of TAp73 protein stability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Anti-GAPDH, anti-p53 (FL393), anti-Hsp90, anti-β-catenin, and anti-HDAC2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-HA (clone 16B12) was purchased from Covance (San Diego, CA). Anti-TAp73 (BL906) was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX). Anti-Occuludin was purchased from Invitrogen. Anti-acetylated lysine was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-actin, trichostatin, cycloheximide, camptothecin, doxorubicin, proteinase inhibitor mixture, and protein A/G beads were purchased from Sigma. Scrambled siRNA (GCA GUG UCU CCA CGU ACU A) and siRNA against HDAC1 (GAG CGA CUG UUU GAG AAC C) or TAp73 (GGC AUG ACU ACA UCU GUC A) were purchased from Dharmacon RNA Technologies (Chicago, IL). 17-Allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) and lactacystin were purchased from A.G. Scientific (San Diego, CA). TnT T7 and the SP6 quick coupled transcription/translation system were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Expressed sequence tag clones that contain a full-length Hsp90 (clone ID 3621040) or HDAC1 (clone ID 2820260) were purchased from Openbiosystem (Huntsville, AL). SAHA (Vorinostat) was a gift from Merck.

Cell Culture and Cell Line Generation

RKO, HCT116, p53−/− HCT116, and H1299 cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) as previously described (63). The stable RKO cell line that inducibly expresses HDAC1 shRNA was generated based on the Tet-on inducible system as previously described (64). Briefly, pTER vector that can express an shRNA against HDAC1 driven by the tetracycline-regulated polymerase III promoter generated in a previous study (40) was transfected into parental RKO cells expressing a Tet Repressor (pcDNA6) (63). The cells were selected with Zeocin and confirmed by Western blot analysis. To induce expression of HDAC1 shRNA, doxycycline (0.5 μg/ml), a tetracycline analog, was added to the medium for various times.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

These assays were performed as previously described (53). Briefly, for immunoprecipitation, the cells were lysed in 0.5% Triton lysis buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 25 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100) supplemented with the proteinase inhibitor mixture (100 μg/ml), followed by incubation with 1 μg of antibody or control IgG overnight. The immunocomplexes were brought down by protein A/G beads and subjected to Western blot analysis. For Western blot analysis, cell lysates, prepared using 2× SDS sample buffer, were separated in 8–12% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with indicated antibodies. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) using the ChemiDoc-It imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA). The level of protein was quantified by densitometry with Software LabWorks (UVP).

Wound Scratch Assay

Confluent monolayer cells grown in a 6-well plate were scratched with a P200 micropipette tip and washed two times with PBS. Phase contrast microscopy photomicrographs were taken using a Canon EOS 40D digital camera (Canon, Lake Success, NY) immediately after scratch (0 h) and 18 h later. Cell migration was determined by visual assessment of cells migrating into the wound area.

Statistical Analysis

All of the experiments were performed in triplicate. Two-group comparisons were analyzed by two-sided Student's t test. p values were calculated, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

HDAC Inhibitors Repress TAp73 Expression at Transcriptional and Post-translational Levels

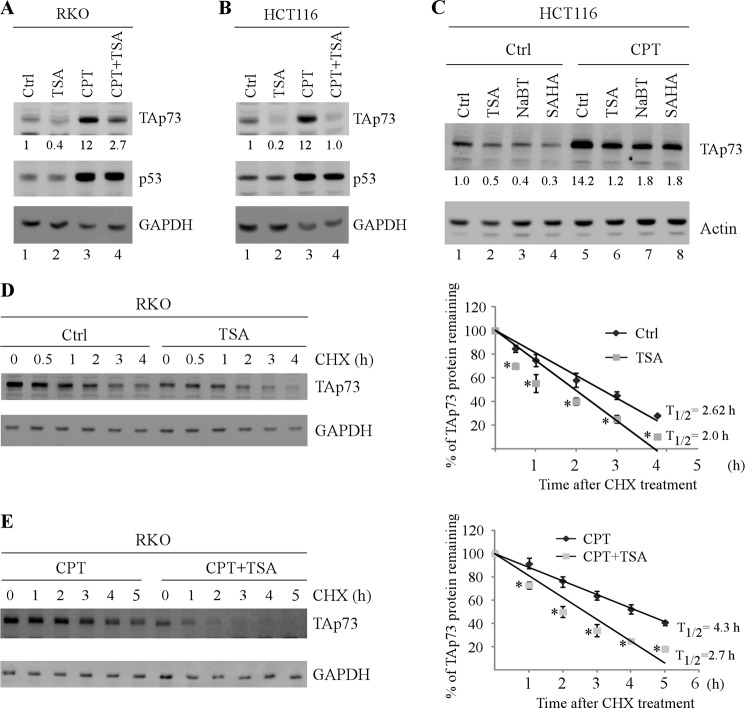

To explore the potential regulation of TAp73 by HDACs, trichostatin (TSA), a pan-HDAC inhibitor, was used to treat RKO and HCT116 cells in the presence or absence of camptothecin, a DNA damage reagent known to induce TAp73 expression (23). Consistent with a previous report (23), the level of TAp73 protein was markedly accumulated by camptothecin in RKO and HCT116 cells (Fig. 1, A and B, compare lane 3 with lane 1). We would like to note that the α isoform of TAp73 was highly expressed and easily detectable by Western blotting. Thus, TAp73α was used to represent TAp73 expression, and TAp73 and TAp73α were used interchangeably. Here, we found that TSA significantly decreased TAp73 expression regardless of camptothecin treatment (Fig. 1, A and B, TAp73 panels, compare lanes 1 and 3 with lanes 2 and 4, respectively). By contrast, TSA had little, if any, effect on p53 expression (Fig. 1, A and B, p53 panels). Similarly, the level of TAp73 protein was repressed by TSA in mutant p53-containing SW480 cells, regardless of camptothecin treatment (supplemental Fig. S1). Furthermore, we found that like TSA, pan-HDACIs, sodium butyrate, and SAHA, were able to inhibit TAp73 expression in HCT116 cells in the presence or absence of camptothecin treatment (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 1 and 5 with lanes 2–4 and 6–8, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

HDAC inhibitors repress TAp73 expression at transcriptional and post-translational levels. A and B, the level of TAp73 protein was repressed by TSA regardless of DNA damage agent. RKO (A) and HCT116 (B) cells were mock treated or treated with camptothecin (250 nm) for 12 h, followed by treatment with or without TSA (50 ng/ml) for 8 h. Cell lysates were collected, and the levels of TAp73, p53, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of GAPDH and arbitrarily set at 1.0. The fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. C, HCT116 cells were mock treated or treated with camptothecin (250 nm) for 12 h, followed by treatment with or without TSA (50 ng/ml), sodium butyrate (NaBT) (5 mm), or SAHA (5 μm) for 8 h. Cell lysates were collected, and the levels of TAp73 and actin were determined by Western blot analysis. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of GAPDH and arbitrarily set at 1.0. The fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. D, TSA destabilizes TAp73 protein under nonstress conditions. RKO cells were mock treated or treated with TSA (50 ng/ml) for 8 h, followed by treatment with or without cycloheximide (50 ng/ml) for various times, and the half-life of TAp73 protein was determined. Left panel, the levels of TAp73 and actin were measured by Western blot analysis. Right panel, the relative level of TAp73 protein was quantified by densitometry and normalized to that of GAPDH. The relative half-life of TAp73 protein was calculated by plotting the percentage of protein left versus time of cycloheximide treatment. The data are presented as the means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test (n = 3 per group). E, TSA destabilizes TAp73 protein under DNA damage-induced conditions. The experiment was performed the same as in D except that RKO cells were treated with CPT (250 nm) for 12 h prior to treatment with or without TSA. The data are presented as the means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test (n = 3 per group). Ctrl, control; CHX, cycloheximide; CPT, camptothecin.

HDACIs are known to modulate gene expression through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. Thus, to explore how HDACI regulates p73 expression, the level of TAp73 and ΔNp73 mRNA was measured by RT-PCR analysis and found to be decreased by TSA (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C). Additionally, we determined whether TSA regulates the half-life of TAp73 protein. Specifically, RKO cells were mock treated or treated with TSA in the presence or absence of camptothecin, followed by treatment with cycloheximide to inhibit de novo protein synthesis for various times. Significantly, we found that in the absence of camptothecin, TSA was able to decrease the half-life of TAp73 protein from 2.62 to 2 h (Fig. 1D), whereas in the presence of camptothecin, the half-life was decreased from 4.3 to 2.7 h (Fig. 1E). We also found that camptothecin prolonged the TAp73 half-life from 2.62 to 4.3 h, consistent with previous report (48, 49). Together, these data suggest that HDAC inhibitors repress TAp73 expression at transcriptional and post-translational levels.

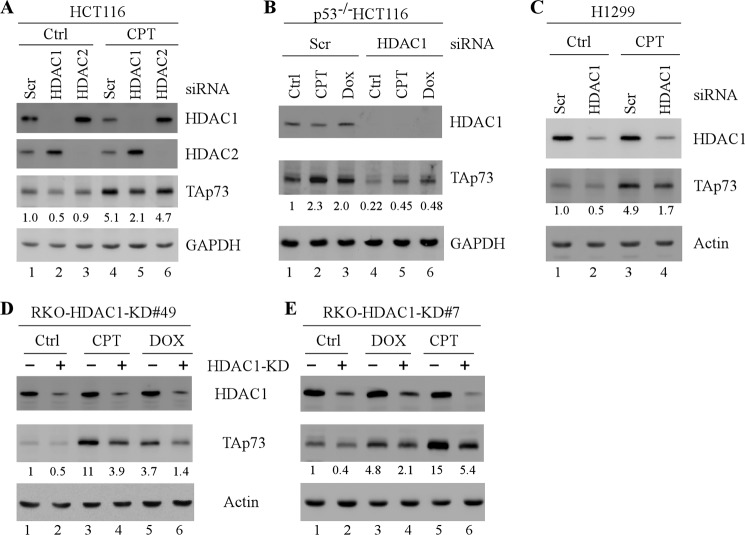

HDAC1 Is Required for TAp73 Expression under Normal and DNA Damage-induced Conditions

Because pan-HDACIs inhibit the activity of class I, II, and IV HDACs, we sought to determine the role of individual HDACs in regulating TAp73 expression. To address this, scrambled siRNA and siRNA against HDAC1 or HDAC2 were transiently transfected into HCT116 cells, followed by treatment with or without camptothecin. As shown in Fig. 2A, both HDAC1 and HDAC2 were efficiently knocked down upon siRNA transfection. Interestingly, we found that knockdown of HDAC1, but not HDAC2, markedly decreased TAp73 expression under normal and DNA-damage induced conditions (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 and 4 with lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6, respectively). Consistent with this, the level of TAp73 protein was decreased by HDAC1 knockdown regardless of DNA damage treatment in p53−/− HCT116 (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 1–3 with lanes 4–6, respectively), as well as in H1299 cells (Fig. 2C, compare lanes 1 and 3 with lanes 2 and 4, respectively). Next, to further verify the regulation of TAp73 by HDAC1, RKO cells were used to generate stable cell lines that can inducibly express an HDAC1 shRNA as previously described (44). Two representative clones were selected for further analysis (Fig. 2, D and E). We showed that upon shRNA induction, the level of HDAC1 was significantly reduced (Fig. 2, D and E, HDAC1 panels). Importantly, TAp73 expression was markedly decreased by HDAC1 knockdown regardless of DNA damage treatment (Fig. 2, D and E, TAp73 panels, compare lanes 1, 3, and 5 with lanes 2, 4, and 6, respectively). Together, these data indicate that HDAC1 is required for TAp73 expression under normal and DNA damage-induced conditions.

FIGURE 2.

HDAC1 is required for TAp73 expression under normal and DNA-damage induced conditions. A, HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with a scrambled siRNA or siRNAs against HDAC1 or HDAC2 for 3 days, followed by mock or camptothecin (250 nm) treatment for 12 h. Cell lysates were collected, and the levels of TAp73, HDAC1, HDAC2, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of GAPDH and arbitrarily set at 1.0. The fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. B, p53−/− HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with a scrambled or HDAC1 siRNA for 3 days, followed by treatment with or without camptothecin (250 nm) or doxorubicin (250 μg/ml) for 12 h. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis to determine the levels of TAp73, HDAC1, and actin. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of GAPDH and arbitrarily set at 1.0. The fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. C, the experiment was performed similarly as in B except that H1299 cells were used. D and E, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to express an HDAC1 shRNA for 3 days, followed by treatment with or without camptothecin (250 nm) or doxorubicin (250 μg/ml) for 12 h. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis to determine the levels of HDAC1, TAp73, and actin. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of GAPDH and arbitrarily set at 1.0. The fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Ctrl, control; Dox or DOX, doxorubicin; CPT, camptothecin.

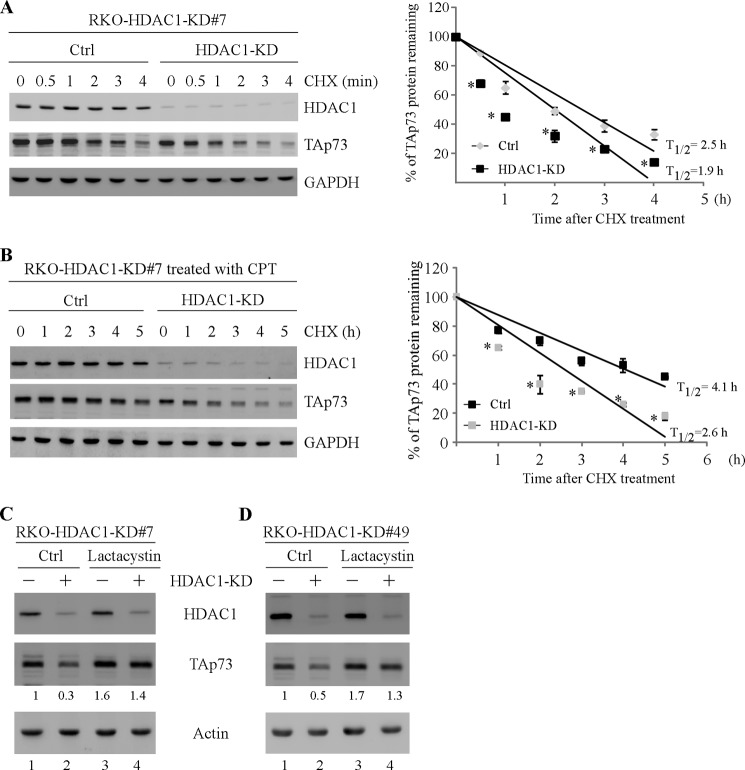

Knockdown of HDAC1 Destabilizes TAp73 Protein by Promoting Its Proteasomal Degradation

To explore the underlying mechanism by which HDAC1 regulates TAp73 expression, the level of TAp73 mRNA was measured by quantitative RT-PCR analysis and found not to be altered by HDAC1 knockdown (supplemental Fig. S2). These data let us speculate that HDAC1 may regulate TAp73 protein stability. In this regard, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days, followed by treatment with or without camptothecin, and then the half-life of TAp73 protein was determined upon cycloheximide treatment. We found that HDAC1 knockdown markedly reduced the half-life of TAp73 protein from 2.5 to 1.9 h in the absence of camptothecin (Fig. 3A) and from 4.1 to 2.6 h in the presence of camptothecin (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that HDAC1 knockdown destabilizes TAp73 protein under normal and DNA-damage induced conditions. Next, because p73 is known to be degraded mainly through the proteasome pathway (50, 51), we thus asked whether the destabilization of TAp73 by HDAC1 knockdown can be relieved by the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin. As shown in Fig. 3 (C and D), TAp73 expression was mildly increased by lactacystin (Fig. 3, C and D, compare lane 1 with lane 3), consistent with previous report (52). Importantly, we found that lactacystin markedly abrogated the inhibition of TAp73 by HDAC1 knockdown (Fig. 3, C and D, compare lanes 1 and 3 with lanes 2 and 4, respectively). Together, these data indicate that knockdown of HDAC1 destabilizes TAp73 protein by targeting its proteasomal degradation.

FIGURE 3.

Knockdown of HDAC1 destabilizes TAp73 protein by promoting its proteasomal degradation. A, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to express an HDAC1 shRNA for 3 days, followed by treatment with cycloheximide for various times, and the half-life of TAp73 protein was determined. Left panel, the levels of HDAC1, TAp73, and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Right panel, the relative level of TAp73 protein was quantified by densitometry and normalized to that of GAPDH. The relative half-life of TAp73 protein was calculated by plotting the percentage of remaining protein versus time of cycloheximide treatment. The data are presented as the means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test (n = 3 per group). B, the experiment was performed similarly as in A except that RKO cells with or with HDAC1 knockdown were treated with camptothecin (250 nm) for 12 h prior to cycloheximide treatment. The data are presented as the means ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 by Student's t test (n = 3 per group). C and D, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days, followed by mock or lactacystin (5 nm) treatment for 8 h. Cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis to determine the levels of HDAC1, TAp73, and actin. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of actin and arbitrarily set at 1.0, and the fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Ctrl, control; CHX, cycloheximide.

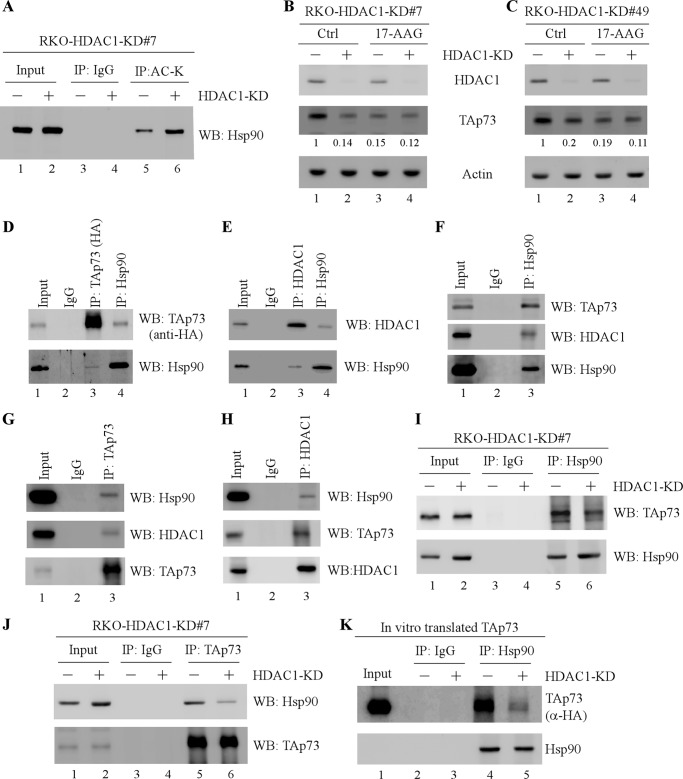

HDAC1 Knockdown Induces Hyperacetylation of Hsp90 and Disrupts Its Association with TAp73

HDACs are known to modulate protein stability by regulating acetylation status of nonhistone protein (53). In addition, TAp73 protein stability is known to be regulated through acetylation (27). Thus, we examined whether TAp73 acetylation is regulated by HDACI or HDAC1 knockdown and found not to be altered (supplemental Fig. S3 and data not shown). These data suggest that other effectors are involved in HDAC1-regulated p73 protein stability. One potential candidate is heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), an essential molecular chaperone, involved in maintaining the folding, stability, and function of many proteins (54). Indeed, several studies indicated that hyperacetylation of Hsp90 by HDACI inactivates its chaperone activity and consequently promotes the proteasomal degradation of its misfolded client proteins (55, 56). In this regard, we determined whether HDAC1 knockdown affects acetylation of Hsp90 by immunoprecipitation-Western blot analysis. Indeed, we found that Hsp90 acetylation was substantially increased by HDAC1 knockdown (Fig. 4A, compare lane 5 with lane 6), suggesting that HDAC1 functions as an Hsp90 deacetylatase in vivo. Next, we examined whether Hsp90 is involved in HDAC1-regulated TAp73 protein stability. To address this, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days, followed by treatment with or without 17-AAG, an Hsp90 inhibitor. We found that TAp73 expression was decreased by 17-AAG (Fig. 4, B and C, compare lane 1 with lane 3). Significantly, inhibition of TAp73 by 17-AAG was not further enhanced by HDAC1 knockdown (Fig. 4, B and C, compare lanes 1 and 3 with lanes 2 and 4, respectively). These data suggest that TAp73 is a client protein of Hsp90, and the chaperone activity of Hsp90 is required for HDAC1 to regulate TAp73 protein stability. Thus, we hypothesize that knockdown of HDAC1 inactivates the chaperone activity of Hsp90 and disrupts its association with TAp73, thereby targeting TAp73 for proteasomal degradation. To test this, we first examined whether Hsp90 directly associates with HDAC1 or TAp73. We found that in vitro translated Hsp90 formed a complex with HA-tagged TAp73 (Fig. 4D) or HDAC1 (Fig. 4E). To further verify this, RKO cells were used for immunoprecipitation-Western analyses with antibodies against Hsp90, TAp73, or HDAC1 along with an isotype control IgG. We found that both TAp73 and HDAC1 were present in the Hsp90 immunocomplex, but not in the control IgG immunocomplex (Fig. 4F, lane 3). Consistent with this, Hsp90 was present in the TAp73 and HDAC1 immunocomplexes (Fig. 4, G and H, lanes 3). We also showed that TAp73 physically interacted with HDAC1 (Fig. 4, G and H, lanes 3), consistent with previous report (57). Next, we determined whether HDAC1 knockdown would affect the association between TAp73 and Hsp90. To address this, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days, followed by immunoprecipitation-Western analyses with antibodies against TAp73 or Hsp90. We would like to mention that HDAC1 knockdown decreased TAp73 expression (Fig. 2). Thus, to ensure similar amounts of TAp73 protein immunoprecipitated, more total lysates were used for HDAC1 knockdown cells than that for control cells. We found that the association between Hsp90 and TAp73 was reduced in RKO cells with HDAC1 knockdown as compared with that in control (Fig. 4, I and J, compare lanes 5 with lanes 6). To verify this, we performed an in vitro binding assay by incubating equal amounts of in vitro translated HA-tagged TAp73 protein with equal amount of Hsp90 protein immunoprecipitated from RKO cells with or without HDAC1 knockdown. We found that the association of in vitro translated TAp73 with endogenous Hsp90 was reduced by HDAC1 knockdown (Fig. 4K, compare lane 4 with lane 5). Together, these data suggest that HDAC1 knockdown results in hyperacetylation and decreased chaperone activity of Hsp90, thereby leading to p73 protein degradation.

FIGURE 4.

HDAC1 knockdown induces hyperacetylation of Hsp90 and disrupts its association with TAp73. A, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of acetylated lysine (AC-K) antibody or isotype control IgG, followed by Western blot analysis with anti-Hsp90. Approximately 2% of lysates was used as input. B and C, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days, followed by mock or 17-AAG (1 μm) treatment for 8 h. Cell lysates were collected, and the levels of HDAC1, TAp73, and actin were determined by Western blot analysis. The basal level of TAp73 was normalized to that of actin and arbitrarily set at 1.0. The fold change is shown below each lane. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. D, Hsp90 physically interacts with HA-tagged TAp73α in vitro. HA-tagged TAp73α and Hsp90 expression vector (1 μg) was used for coupled in vitro transcription/translation reactions according to the users' manual. Equal volumes of in vitro translated HA-TAp73α and Hsp90 protein lysates were mixed and subjected to immunoprecipitation with 1 μg of HA or Hsp90 antibody or a control IgG. The immunocomplexes were examined by Western blot analysis with anti-HA (top panel) or anti-Hsp90 (bottom panel). E, the experiment was performed the same as in D except that HDAC1 expression vector was used. F, RKO whole cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of Hsp90 antibody or control IgG, followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies against TAp73, HDAC1, or Hsp90. Approximately 2% of lysates was used as input. G and H, the experiment was performed similarly as in D except that RKO cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of TAp73 (G) or HDAC1 (H) antibody. I and J, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of control IgG or antibodies against Hsp90 (I) or TAp73 (J), followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies against TAp73 or Hsp90. Approximately 2% of lysates was used as input. K, Hsp90 protein immunoprecipitated from RKO cell lysates with or without HDAC1 knockdown was incubating with equal amount of in vitro translated HA-tagged TAp73α protein for 4 h. The immunocomplexes were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-HA or anti-Hsp90. Ctrl, control; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

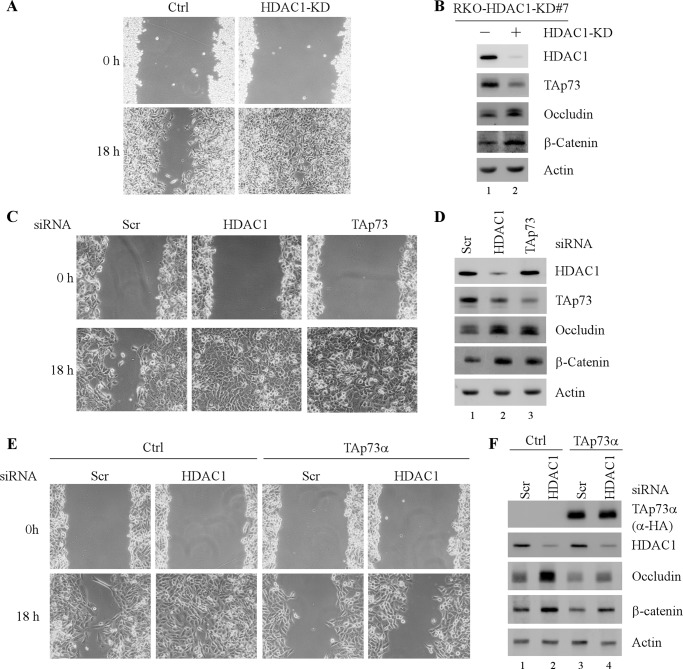

TAp73 Is a Critical Downstream Mediator of HDAC1-regulated Cell Migration

Both p73 and HDACs have a profound effect on cell growth and migration. Thus, to determine the physiological significance of HDAC1-regulated p73 expression, cell migration was measured by a scratch wound assay in RKO cells with or without HDAC1 knockdown. Interestingly, we found that HDAC1 knockdown resulted in an enhanced cell migration (Fig. 5A, compare lower left and right panels). To verify this, the expression of occludin and β-catenin, both of which are known to promote cell migration (58, 59), was measured and found to be increased by HDAC1 knockdown, concomitantly with decreased expression of TAp73 (Fig. 5B, compare lane 1 with lane 2). Notably, TAp73 was found to inhibit cell migration in MCF10A cells (60), and thus, it is likely that TAp73 plays a role in the enhanced cell migration by HDAC1 knockdown. Therefore, cell migration was measured in H1299 cells transiently transfected with a scrambled siRNA or siRNA against TAp73 or HDAC1. We found that like HDAC1 knockdown, TAp73 knockdown resulted in increased cell migration in H1299 cells (Fig. 5C, compare lower left panel with lower middle and right panels, respectively), along with increased expression of occludin and β-catenin (Fig. 5D, compare lane 1 with lanes 2 and 3). Consistent with this, ectopic expression of TAp73 significantly inhibited cell migration in H1299 cells (supplemental Fig. S4, A and B). In addition, we showed that although p73 is known to suppress cell proliferation, the level of TAp73α expressed in this assay was insufficient to induce growth suppression (supplemental Fig. S4, C and D), suggesting that the altered cell migration by overexpression or knockdown of TAp73 was not due to changes in cell proliferation (supplemental Fig. S4, C and D). Together, these data suggest that TAp73 may be a downstream mediator of HDAC1-regulated cell migration. To verify this, H1299 cells were transiently transfected with a scrambled or HDAC1 siRNA along with or without ectopic TAp73α expression, followed by a scratch wound assay. We found that in the absence of ectopic TAp73α, HDAC1 knockdown markedly increased cell migration (Fig. 5E, compare lower left two panels). By contrast, in the presence of ectopic TAp73α, HDAC1 knockdown can only slightly stimulate cell migration (Fig. 5E, compare lower right two panels). Consistent with this, the increased expression of occludin and β-catenin by HDAC1 knockdown was markedly attenuated by ectopic TAp73α (Fig. 5F, compare lanes 1 and 3 with lanes 2 and 4, respectively). Together, these data indicated that decreased TAp73 expression is required for the enhanced cell migration by HDAC1 knockdown.

FIGURE 5.

TAp73 is a critical downstream mediator of HDAC1-regulated cell migration. A, RKO cells were uninduced or induced to knock down HDAC1 for 3 days. After induction, confluent monolayers cells were scratched by a pipette tip. Phase contrast photomicrographs were taken immediately after scratch (0 h) and 18 h later to monitor cell migration. B, lysates from cells treated as in A were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against HDAC1, TAp73, occludin, β-catenin and actin. C, H1299 cells transiently transfected with a scrambled siRNA or siRNAs against HDAC1 or TAp73 for 3 days, followed by a scratch wound assay as describe in A. D, lysates from cells treated as in C were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against HDAC1, TAp73, occludin, β-catenin, and actin. E, H1299 cells transiently transfected with a scrambled or HDAC1 siRNA for 2 day and then transfected with a control vector or a vector expressing HA-tagged TAp73α for 1 day, followed by a scratch wound assay as described in A. F, lysates from cells treated as in E were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against HA (for TAp73α), HDAC1, occludin, β-catenin, and actin.

DISCUSSION

p73 is rarely mutated in cancers, and activation of TAp73 is an attractive strategy to manage tumor cells, especially for those wherein p53 is inactivated. Thus, understanding the p73 pathway is of greater interest. In the current study, we found that HDAC1 is a key regulator of TAp73 protein stability. Specifically, we found that HDAC1 inhibition by HDACI or siRNA reduces the half-life of TAp73 protein, leading to decreased TAp73 expression regardless of DNA damage treatments. To uncover the underlying mechanism, we found that knockdown of HDAC1 results in hyperacetylation and inactivation of Hsp90 and prevents it from binding to TAp73, thereby resulting in proteasomal degradation of TAp73. Finally, we found that reduced TAp73 expression is required for the enhanced cell migration by HDAC1 knockdown. Together, we uncover a novel regulation of TAp73 protein stability by HDAC1-Hsp90 chaperone axis.

In our study, we showed that HDACI is capable of destabilizing TAp73 protein under normal and DNA damage-induced conditions via inhibition of HDAC1 (Figs. 1–3). Interestingly, we also found that HDACIs significantly decrease the level of TAp73 mRNA (supplemental Fig. S1B). These results suggest that other HDACs are involved in regulating TAp73 transcription, although the underlying mechanism is not clear. Recently, HDAC8, a class I HDAC, was found to regulate p53 transcription via transcription factor HoxA5 (45). In addition, the activity of E2F1, a known p73 regulator, is found to be regulated by HDACI (61). Thus, these possibilities need to be examined in the future studies to elucidate how HDACI transcriptionally represses TAp73 expression. Moreover, at this moment, it is not clear whether expression and activity of ΔNp73, the oncogenic p73 isoform known to antagonize the full-length TAp73 and p53, can be regulated by HDACs. Considering that the ratio between TAp73 and ΔNp73 is critical for tumor suppression and development, it would be important to determine whether HDACs regulates ΔNp73 expression and whether this regulation would affect the balance between TAp73 and ΔNp73. Finally, we would like to mention that all three p53 family members are regulated by different HDACs via transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms (Refs. 42 and 44–47 and TAp73 by HDAC1 from this study). Thus, a systematic evaluation of the regulations of the p53 family by HDACs in various biological processes would shed considerable light into the cross-talk between these important regulators and their roles in tumorigenesis.

We found that the Hsp90 inhibitor 17-AAG is able to decrease TAp73 expression (Fig. 4, B and C, compare lane 1 with lane 3). Moreover, Hsp90 physically associates with TAp73 (Fig. 4, D and E). These data suggest that TAp73 is a client protein of Hsp90. However, several questions remain to be addressed. For example, domains in TAp73 and Hsp90 responsible for their interaction need to be mapped. Moreover, it is not clear whether other co-chaperones are involved in this regulation. Furthermore, we would like to note that Hsp90 associates with mutant p53 and prevents it from proteasomal degradation (46, 68), whereas Hsp90 associates with wild-type p53 and modulates its transcriptional activity (68). Because TAp73 has many features like wild-type p53, it will be interesting to determine whether Hsp90 affects TAp73 transcriptional activity in addition to regulate its protein stability. Finally, it is not clear how TAp73 is degraded following Hsp90 inactivation, and thus, the E3 ligase(s) involved in this process needs to be identified. Most importantly, targeting these E3 ligase(s) in combination with Hsp90 inhibition may provide a new strategy for improvement of cancer treatment.

In addition to TAp73, inactivation of Hsp90 upon treatment of HDACI or knockdown of HDAC1 enhances proteasomal degradation of Her-2, FLT-3, and DNMT1 (62–64). Furthermore, inhibition of HDAC6, a class II HDAC member, and subsequent inactivation of Hsp90 led to enhanced degradation of glucocorticoid receptor, Bcr-Abl, and mutant p53 (46, 55, 65). Together, these results suggest that HDAC inhibition could potentially affect both oncoproteins and tumor suppressors via Hsp90. This may account for some of observed pleiotropic effects of HDACI in clinical treatment. Because TAp73 can be activated by chemotherapeutic drugs to induce p53-independent cell death, precautions need to be taken when combining conventional chemotherapies with HDAC or Hsp90 inhibition-directed cancer treatment. Notably, HDAC inhibition does not uniformly affect all Hsp90 client proteins (66), suggesting that different molecular effectors are involved in destabilizing its client protein following Hsp90 inactivation. Thus, identifying these molecular effectors may have important implications for the improvement of HDAC or Hsp90 inhibitor-directed cancer treatment by specifically preventing the degradation of tumor suppressors, like TAp73.

Acknowledgment

We thank S. Townson (Merck & Co., Inc.) for providing SAHA (Vorinostat).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA081237 and CA076069.

This article contains supplemental text and Figs. S1–S4.

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- HDACI

- HDAC inhibitor

- SAHA

- suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- 17-AAG

- allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin

- TSA

- trichostatin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harms K., Nozell S., Chen X. (2004) The common and distinct target genes of the p53 family transcription factors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 822–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray-Zmijewski F., Lane D. P., Bourdon J. C. (2006) p53/p63/p73 isoforms. An orchestra of isoforms to harmonise cell differentiation and response to stress. Cell Death Differ. 13, 962–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fontemaggi G., Kela I., Amariglio N., Rechavi G., Krishnamurthy J., Strano S., Sacchi A., Givol D., Blandino G. (2002) Identification of direct p73 target genes combining DNA microarray and chromatin immunoprecipitation analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43359–43368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grob T. J., Novak U., Maisse C., Barcaroli D., Lüthi A. U., Pirnia F., Hügli B., Graber H. U., De Laurenzi V., Fey M. F., Melino G., Tobler A. (2001) Human ΔNp73 regulates a dominant negative feedback loop for TAp73 and p53. Cell Death Differ. 8, 1213–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kartasheva N. N., Contente A., Lenz-Stöppler C., Roth J., Dobbelstein M. (2002) p53 induces the expression of its antagonist p73ΔN, establishing an autoregulatory feedback loop. Oncogene 21, 4715–4727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakagawa T., Takahashi M., Ozaki T., Watanabe Ki K., Todo S., Mizuguchi H., Hayakawa T., Nakagawara A. (2002) Autoinhibitory regulation of p73 by ΔNp73 to modulate cell survival and death through a p73-specific target element within the ΔNp73 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2575–2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu G., Nozell S., Xiao H., Chen X. (2004) ΔNp73β is active in transactivation and growth suppression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 487–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cui R., Nguyen T. T., Taube J. H., Stratton S. A., Feuerman M. H., Barton M. C. (2005) Family members p53 and p73 act together in chromatin modification and direct repression of α-fetoprotein transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39152–39160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldschneider D., Million K., Meiller A., Haddada H., Puisieux A., Bénard J., May E., Douc-Rasy S. (2005) The neurogene BTG2TIS21/PC3 is transactivated by ΔNp73α via p53 specifically in neuroblastoma cells. J. Cell Sci. 118, 1245–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tissir F., Ravni A., Achouri Y., Riethmacher D., Meyer G., Goffinet A. M. (2009) ΔNp73 regulates neuronal survival in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16871–16876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilhelm M. T., Rufini A., Wetzel M. K., Tsuchihara K., Inoue S., Tomasini R., Itie-Youten A., Wakeham A., Arsenian-Henriksson M., Melino G., Kaplan D. R., Miller F. D., Mak T. W. (2010) Isoform-specific p73 knockout mice reveal a novel role for ΔNp73 in the DNA damage response pathway. Genes Dev. 24, 549–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomasini R., Tsuchihara K., Wilhelm M., Fujitani M., Rufini A., Cheung C. C., Khan F., Itie-Youten A., Wakeham A., Tsao M. S., Iovanna J. L., Squire J., Jurisica I., Kaplan D., Melino G., Jurisicova A., Mak T. W. (2008) TAp73 knockout shows genomic instability with infertility and tumor suppressor functions. Genes Dev. 22, 2677–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rufini A., Niklison-Chirou M. V., Inoue S., Tomasini R., Harris I. S., Marino A., Federici M., Dinsdale D., Knight R. A., Melino G., Mak T. W. (2012) TAp73 depletion accelerates aging through metabolic dysregulation. Genes Dev. 26, 2009–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Irwin M. S., Kondo K., Marin M. C., Cheng L. S., Hahn W. C., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2003) Chemosensitivity linked to p73 function. Cancer Cell 3, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergamaschi D., Gasco M., Hiller L., Sullivan A., Syed N., Trigiante G., Yulug I., Merlano M., Numico G., Comino A., Attard M., Reelfs O., Gusterson B., Bell A. K., Heath V., Tavassoli M., Farrell P. J., Smith P., Lu X., Crook T. (2003) p53 polymorphism influences response in cancer chemotherapy via modulation of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell 3, 387–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kovalev S., Marchenko N., Swendeman S., LaQuaglia M., Moll U. M. (1998) Expression level, allelic origin, and mutation analysis of the p73 gene in neuroblastoma tumors and cell lines. Cell Growth Differ. 9, 897–903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Irwin M., Marin M. C., Phillips A. C., Seelan R. S., Smith D. I., Liu W. (2000) Role for the p53 homologue p73 in E2F-1-induced apoptosis. Nature 407, 645–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stiewe T., Pützer B. M. (2000) Role of the p53-homologue p73 in E2F1-induced apoptosis. Nat. Genet. 26, 464–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seelan R. S., Irwin M., van der Stoop P., Qian C., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Liu W. (2002) The human p73 promoter. Characterization and identification of functional E2F binding sites. Neoplasia 4, 195–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu S., Murai S., Kataoka K., Miyagishi M. (2008) Yin Yang 1 induces transcriptional activity of p73 through cooperation with E2F1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 365, 75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fontemaggi G., Gurtner A., Strano S., Higashi Y., Sacchi A., Piaggio G., Blandino G. (2001) The transcriptional repressor ZEB regulates p73 expression at the crossroad between proliferation and differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8461–8470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marabese M., Vikhanskaya F., Rainelli C., Sakai T., Broggini M. (2003) DNA damage induces transcriptional activation of p73 by removing C-EBPα repression on E2F1. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 6624–6632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Urist M., Tanaka T., Poyurovsky M. V., Prives C. (2004) p73 induction after DNA damage is regulated by checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2. Genes Dev. 18, 3041–3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pediconi N., Ianari A., Costanzo A., Belloni L., Gallo R., Cimino L., Porcellini A., Screpanti I., Balsano C., Alesse E., Gulino A., Levrero M. (2003) Differential regulation of E2F1 apoptotic target genes in response to DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 552–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ozaki T., Okoshi R., Sang M., Kubo N., Nakagawara A. (2009) Acetylation status of E2F-1 has an important role in the regulation of E2F-1-mediated transactivation of tumor suppressor p73. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 386, 207–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yan W., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Jung Y. S., Chen X. (2012) p73 expression is regulated by RNPC1, a target of the p53 family, via mRNA stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2336–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Costanzo A., Merlo P., Pediconi N., Fulco M., Sartorelli V., Cole P. A., Fontemaggi G., Fanciulli M., Schiltz L., Blandino G., Balsano C., Levrero M. (2002) DNA damage-dependent acetylation of p73 dictates the selective activation of apoptotic target genes. Mol. Cell 9, 175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agami R., Blandino G., Oren M., Shaul Y. (1999) Interaction of c-Abl and p73α and their collaboration to induce apoptosis. Nature 399, 809–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gong J. G., Costanzo A., Yang H. Q., Melino G., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Levrero M., Wang J. Y. (1999) The tyrosine kinase c-Abl regulates p73 in apoptotic response to cisplatin-induced DNA damage. Nature 399, 806–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yuan Z. M., Shioya H., Ishiko T., Sun X., Gu J., Huang Y. Y., Lu H., Kharbanda S., Weichselbaum R., Kufe D. (1999) p73 is regulated by tyrosine kinase c-Abl in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Nature 399, 814–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jones E. V., Dickman M. J., Whitmarsh A. J. (2007) Regulation of p73-mediated apoptosis by c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Biochem. J. 405, 617–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanchez-Prieto R., Sanchez-Arevalo V. J., Servitja J. M., Gutkind J. S. (2002) Regulation of p73 by c-Abl through the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Oncogene 21, 974–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ren J., Datta R., Shioya H., Li Y., Oki E., Biedermann V., Bharti A., Kufe D. (2002) p73β is regulated by protein kinase Cδ catalytic fragment generated in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33758–33765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossi M., De Laurenzi V., Munarriz E., Green D. R., Liu Y. C., Vousden K. H., Cesareni G., Melino G. (2005) The ubiquitin-protein ligase Itch regulates p73 stability. EMBO J. 24, 836–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peschiaroli A., Scialpi F., Bernassola F., Pagano M., Melino G. (2009) The F-box protein FBXO45 promotes the proteasome-dependent degradation of p73. Oncogene 28, 3157–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sayan B. S., Yang A. L., Conforti F., Tucci P., Piro M. C., Browne G. J., Agostini M., Bernardini S., Knight R. A., Mak T. W., Melino G. (2010) Differential control of TAp73 and ΔNp73 protein stability by the ring finger ubiquitin ligase PIR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12877–12882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jung Y. S., Qian Y., Chen X. (2012) Pirh2 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase. Its role in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. FEBS Lett. 586, 1397–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hosoda M., Ozaki T., Miyazaki K., Hayashi S., Furuya K., Watanabe K., Nakagawa T., Hanamoto T., Todo S., Nakagawara A. (2005) UFD2a mediates the proteasomal turnover of p73 without promoting p73 ubiquitination. Oncogene 24, 7156–7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dokmanovic M., Clarke C., Marks P. A. (2007) Histone deacetylase inhibitors. Overview and perspectives. Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 981–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marks P., Rifkind R. A., Richon V. M., Breslow R., Miller T., Kelly W. K. (2001) Histone deacetylases and cancer. Causes and therapies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 1, 194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bolden J. E., Peart M. J., Johnstone R. W. (2006) Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 769–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luo J., Su F., Chen D., Shiloh A., Gu W. (2000) Deacetylation of p53 modulates its effect on cell growth and apoptosis. Nature 408, 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Juan L. J., Shia W. J., Chen M. H., Yang W. M., Seto E., Lin Y. S., Wu C. W. (2000) Histone deacetylases specifically down-regulate p53-dependent gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20436–20443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harms K. L., Chen X. (2007) Histone deacetylase 2 modulates p53 transcriptional activities through regulation of p53-DNA binding activity. Cancer Res. 67, 3145–3152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yan W., Liu S., Xu E., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Chen X. (2013) Histone deacetylase inhibitors suppress mutant p53 transcription via histone deacetylase 8. Oncogene 32, 599–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li D., Marchenko N. D., Moll U. M. (2011) SAHA shows preferential cytotoxicity in mutant p53 cancer cells by destabilizing mutant p53 through inhibition of the HDAC6-Hsp90 chaperone axis. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1904–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Qian Y., Jung Y. S., Chen X. (2011) ΔNp63, a target of DEC1 and histone deacetylase 2, modulates the efficacy of histone deacetylase inhibitors in growth suppression and keratinocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 12033–12041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Slade N., Zaika A. I., Erster S., Moll U. M. (2004) ΔNp73 stabilises TAp73 proteins but compromises their function due to inhibitory hetero-oligomer formation. Cell Death Differ. 11, 357–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dulloo I., Sabapathy K. (2005) Transactivation-dependent and -independent regulation of p73 stability. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28203–28214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kramer S., Ozaki T., Miyazaki K., Kato C., Hanamoto T., Nakagawara A. (2005) Protein stability and function of p73 are modulated by a physical interaction with RanBPM in mammalian cultured cells. Oncogene 24, 938–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kikuchi H., Ozaki T., Furuya K., Hanamoto T., Nakanishi M., Yamamoto H., Yoshida K., Todo S., Nakagawara A. (2006) NF-κB regulates the stability and activity of p73 by inducing its proteolytic degradation through a ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway. Oncogene 25, 7608–7617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bálint E., Bates S., Vousden K. H. (1999) Mdm2 binds p73α without targeting degradation. Oncogene 18, 3923–3929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Geng H., Liu Q., Xue C., David L. L., Beer T. M., Thomas G. V., Dai M. S., Qian D. Z. (2012) HIF1α protein stability is increased by acetylation at lysine - K709. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 35496–35505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pearl L. H., Prodromou C. (2006) Structure and mechanism of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone machinery. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 271–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bali P., Pranpat M., Bradner J., Balasis M., Fiskus W., Guo F., Rocha K., Kumaraswamy S., Boyapalle S., Atadja P., Seto E., Bhalla K. (2005) Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90. A novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26729–26734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nimmanapalli R., Fuino L., Bali P., Gasparetto M., Glozak M., Tao J., Moscinski L., Smith C., Wu J., Jove R., Atadja P., Bhalla K. (2003) Histone deacetylase inhibitor LAQ824 both lowers expression and promotes proteasomal degradation of Bcr-Abl and induces apoptosis of imatinib mesylate-sensitive or -refractory chronic myelogenous leukemia-blast crisis cells. Cancer Res. 63, 5126–5135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang J., Chen X. (2007) ΔNp73 modulates nerve growth factor-mediated neuronal differentiation through repression of TrkA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3868–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Du D., Xu F., Yu L., Zhang C., Lu X., Yuan H. (2010) The tight junction protein, occludin, regulates the directional migration of epithelial cells. Dev. Cell 18, 52–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Müller T., Bain G., Wang X., Papkoff J. (2002) Regulation of epithelial cell migration and tumor formation by β-catenin signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 280, 119–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang Y., Yan W., Jung Y. S., Chen X. (2012) Mammary epithelial cell polarity is regulated differentially by p73 isoforms via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 17746–17753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wallace D. M., Cotter T. G. (2009) Histone deacetylase activity in conjunction with E2F-1 and p53 regulates Apaf-1 expression in 661W cells and the retina. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 887–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou Q., Agoston A. T., Atadja P., Nelson W. G., Davidson N. E. (2008) Inhibition of histone deacetylases promotes ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 873–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fuino L., Bali P., Wittmann S., Donapaty S., Guo F., Yamaguchi H., Wang H. G., Atadja P., Bhalla K. (2003) Histone deacetylase inhibitor LAQ824 down-regulates Her-2 and sensitizes human breast cancer cells to trastuzumab, taxotere, gemcitabine, and epothilone B. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2, 971–984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nishioka C., Ikezoe T., Yang J., Takeuchi S., Koeffler H. P., Yokoyama A. (2008) MS-275, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor with selectivity against HDAC1, induces degradation of FLT3 via inhibition of chaperone function of heat shock protein 90 in AML cells. Leukemia Res. 32, 1382–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kovacs J. J., Murphy P. J., Gaillard S., Zhao X., Wu J. T., Nicchitta C. V., Yoshida M., Toft D. O., Pratt W. B., Yao T. P. (2005) HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol. Cell 18, 601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Boyault C., Sadoul K., Pabion M., Khochbin S. (2007) HDAC6, at the crossroads between cytoskeleton and cell signaling by acetylation and ubiquitination. Oncogene 26, 5468–5476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yang A., Walker N., Bronson R., Kaghad M., Oosterwegel M., Bonnin J., Vagner C., Bonnet H., Dikkes P., Sharpe A., McKeon F., Caput D. (2000) p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours. Nature 404, 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Peng Y., Chen L., Li C., Lu W., Chen J. (2001) Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40583–40590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]