Background: The cellulosome N terminus contains the sole substrate-binding module of the cellulosome scaffoldin.

Results: Two N-terminal cellulosomal fragments are devoid of intermodular interactions, are highly dynamic, and inhabit compact and elongated conformations equally.

Conclusion: The characteristics of the cellulosome N terminus may facilitate its role in substrate binding.

Significance: Information on cellulosome structure and dynamics aids in engineering designer cellulosomes.

Keywords: Cell-surface Enzymes, Cellulase, Protein Complexes, Protein Dynamics, Structural Biology, Cellulosome, Modular Assembly, Scaffoldin, Small Angle X-ray Scattering

Abstract

Clostridium thermocellum produces the prototypical cellulosome, a large multienzyme complex that efficiently hydrolyzes plant cell wall polysaccharides into fermentable sugars. This ability has garnered great interest in its potential application in biofuel production. The core non-catalytic scaffoldin subunit, CipA, bears nine type I cohesin modules that interact with the type I dockerin modules of secreted hydrolytic enzymes and promotes catalytic synergy. Because the large size and flexibility of the cellulosome preclude structural determination by traditional means, the structural basis of this synergy remains unclear. Small angle x-ray scattering has been successfully applied to the study of flexible proteins. Here, we used small angle x-ray scattering to determine the solution structure and to analyze the conformational flexibility of two overlapping N-terminal cellulosomal scaffoldin fragments comprising two type I cohesin modules and the cellulose-specific carbohydrate-binding module from CipA in complex with Cel8A cellulases. The pair distribution functions, ab initio envelopes, and rigid body models generated for these two complexes reveal extended structures. These two N-terminal cellulosomal fragments are highly dynamic and display no preference for extended or compact conformations. Overall, our work reveals structural and dynamic features of the N terminus of the CipA scaffoldin that may aid in cellulosome substrate recognition and binding.

Introduction

Cellulose is the major constituent of plant cell walls and the most abundant organic molecule on Earth (1). With increasing energy consumption, the depletion of fossil fuels, and growing environmental concerns, development of alternative fuel sources is paramount. Conversion of plant biomass to ethanol represents a renewable and environmentally friendly alternative to fossil fuels. The critical bottleneck that prevents bioethanol from becoming a competitive energy source is the low efficiency of plant cell wall polysaccharide hydrolysis (2–4). Success in engineering “designer” hydrolases that can effectively break down cellulosic biomass has been limited; however, selected microbial species have been discovered that can rapidly and efficiently degrade plant cell wall polysaccharides through the synergistic activity of a variety of cellulases, hemicellulases, and other hydrolases all assembled in large protein complexes called cellulosomes (5–9).

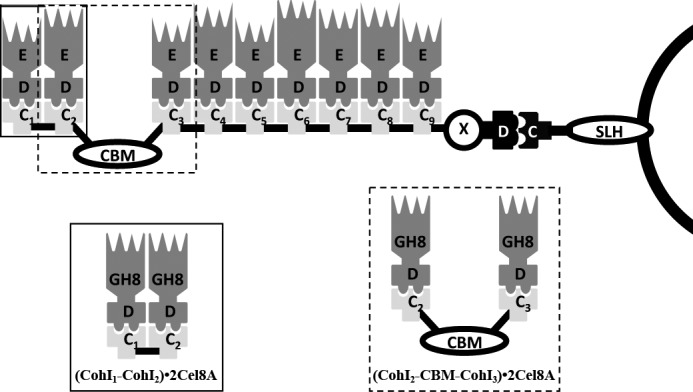

The best studied cellulosome is from the thermophilic anaerobe Clostridium thermocellum and is composed of three main components: a multimodular non-catalytic scaffoldin subunit called CipA, catalytic subunits of varying activities that bear a type I dockerin (DocI),4 and one of the three cell surface-associated proteins that contain one, two, or seven type II cohesin (CohII) modules, i.e. SdbA, Orf2p, and OlpB, respectively (see Fig. 1) (5, 10–13). The CipA scaffoldin subunit comprises a cellulose-specific carbohydrate-binding module (CBM) that targets the multienzyme complex to its substrate, an X module of unknown function, a DocII module responsible for anchoring the scaffoldin to the cell-surface subunit via interaction with its cognate CohII module, and nine CohI modules, all of which are connected by linker regions of varying lengths. The latter cohesins mediate the assembly of the catalytic subunits into the complex via their respective DocI modules (14–19).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the cellulosome from C. thermocellum. The cellulosome is composed of three types of proteins: 1) a cell surface-anchoring protein, 2) the CipA scaffoldin protein, and 3) enzyme subunits. Cell-surface proteins are composed of CohII modules (white C) and surface-like homology (SLH) domains, which interact with the cell surface. CipA is composed of a DocII module (white D), an X module (X), a family 3a cellulose-specific binding module (the CBM), and nine CohI modules (black C1–9) enumerated from the N terminus, which is on the left side in this schematic. Enzyme subunits contain a DocI module (black D) and a catalytic module (black E). The (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes and where they map in the full-length cellulosome are shown in the solid and dashed boxes, respectively.

Despite the fact that many structures of individual modules have now been solved using x-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy (19–25), very little is known about the arrangement of these modules in three-dimensional space that ultimately leads to the characteristic synergy among the cellulosomal enzyme components. Small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) has been used to investigate how linker length and composition affect the modular orientation in the context of engineered chimeric minicellulosome-like complexes (26). This work has provided valuable insight into the behavior of engineered scaffoldins; however, it is unclear how well these complexes represent the behavior of natural scaffoldins. Early EM studies revealed the dynamic nature of the cellulosome ultrastructure (27, 28). In the absence of substrate, the cellulosome forms bulbous protuberances on the surface of the cell. However, in the presence of a crystalline cellulose substrate, the cellulosome forms fibrous structures that adhere to the surface of the cellulose. More recently, single-particle cryo-EM was performed on a fragment of CipA comprising CohI modules 3–5 in tandem (CohI3-CohI4-CohI5), each with bound DocI-bearing Cel8A catalytic components. The data revealed a compact structure, with the enzymes projecting outward in opposite directions (29).

In this study, we investigated the structure and flexibility of two overlapping N-terminal fragments of the cellulosome from C. thermocellum using SAXS. These fragments included the same Cel8A enzyme used in the previous cryo-EM work (29) together with two overlapping CipA scaffoldin fragments: CohI1-CohI2 and CohI2-CBM-CohI3 (Fig. 1). We present the best fit structures determined by ab initio and rigid body methods. We show that a minimal ensemble of conformers better fit the data than a single structure, which indicates that both complexes are flexible. Furthermore, the minimal ensemble analysis depicts equal populations of compact and elongated conformers for both complexes. The structural analysis presented here reveals a high degree of structural dynamics in the N terminus of the cellulosome, which may facilitate substrate recognition and binding by allowing greater access to the CBM of CipA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

The C. thermocellum CipA scaffoldin fragments CohI1-CohI2 (residues 30–321) and CohI2-CBM-CohI3 (residues 184–702) with C-terminal hexahistidine tags were coexpressed with Cel8A (residues 33–477) bearing S458A/S459A mutations to restrict DocI binding to a single orientation. The plasmids and cloning strategy used to generate the coexpression vectors have been described previously (29). The primers used to amplify the CohI1-CohI2 fragment were 5′-CTCGCTAGCACAATGACAGTCGAGATC-3′ and 5′-CACCTCGAGAACGTTAACACCACCGTC-3′. The CohI2-CBM-CohI3 fragment was amplified using primers 5′-CTCGCTAGCGTGGTAGTAGAAATTGGC-3′ and 5′-CACCTCGAGAACATTTACTCCACCGTC-3′.

Plasmids were transformed into TunerTM cells (Invitrogen) and grown in LB broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Cultures were induced with 0.2 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at A600 = 0.6 and grown for an additional 16 h at 19 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 20 min at 4200 rpm using a Sorvall H-6000A/HBB-6 rotor and then resuspended in Buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, and 1 mm CaCl2). Lysozyme (1 mg/ml) was added to the suspension and incubated at 4 °C with stirring for 30 min, followed by sonication. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 rpm using a JA-20 rotor. Ni2+ affinity resin (2 ml) pre-equilibrated with Buffer A was added to the supernatant and incubated at 4 °C with rocking for 1 h. The mixture was subsequently applied to a column containing the affinity resin and washed with Buffer A and eluted with Buffer A containing 400 mm imidazole. The eluted protein was further purified over a Sephadex 200 size exclusion column (Amersham Biosciences) that was pre-equilibrated with 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm DTT. Fractions containing protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Purified complexes were pooled and concentrated.

Dynamic Light Scattering Analysis

Prior to dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements, samples were centrifuged at maximal speed using a tabletop microcentrifuge for 30 min at 4 °C. DLS experiments were performed with a DynaPro instrument (Protein Solutions), and the data were analyzed using the accompanying Dynamics version 5.25.44 software package.

SAXS Data Collection

SAXS data were collected at the F2 station at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (Ithaca, NY) using an ADSC Quantum-210 CCD detector. A sample (6.0 mg/ml) of bovine serum albumin was measured as a reference and for calibration. Samples (25 μl) were oscillated back and forth in the capillary throughout the data collection to minimize sample damage during each exposure. Scattering patterns were measured with a total exposure time of 3 min at 21 °C. The wavelength was 1.25480 Å with a sample-to-detector distance of 800 mm. The scattering vectors (q) covered 0.01–0.4 Å−1. The concentration of the protein samples ranged from 5 to 16 mg/ml for (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and from 1 to 3 mg/ml for (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A. Samples were measured twice with background scattering measurements of the final column flow-through from the protein purification taken both before and after each protein sample to monitor any beam fluctuations or damage to the protein sample. Background scattering was subtracted from the protein scattering patterns after proper normalization and correction for detector response.

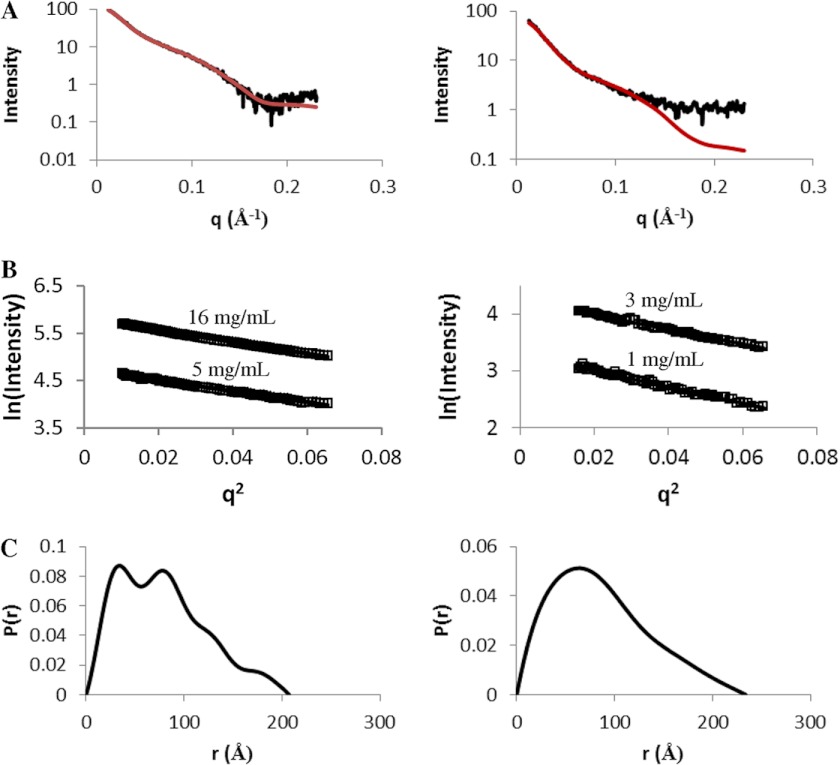

SAXS Data Analysis

The radii of gyration (Rg) were derived from the Guinier approximation: I(q) = I(0)exp(−q2Rg2/3), where I(q) is the scattering intensity and I(0) is the forward scattering intensity (30). Rg and I(0) were determined from the slope and intercept, respectively, of the linear fit of ln(I(q)) versus q2 in the q range q*Rg < 1.3. All scattering curves were indicative of monomeric states of the molecules in solution. The distance distribution function (P(r)) was calculated using the Fourier inversion of the scattering intensity I(q) using GNOM (34). The P(r) function was also used to calculate the Rg, taking into account the whole data collected. The molecular masses of both complexes were determined as described previously (31).

SAXS-based Modeling Procedures

The low-resolution shapes of the protein constructs were determined ab initio from the scattering curve using the programs DAMMIN and GASBOR (32, 33). Rigid body modeling and minimal ensemble generation were performed with BILBOMD (34). Initial models of the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes for BILBOMD analysis were generated with PyMOL using the structures with Protein Data Bank codes 1ANU, 1NBC, 1OHZ, and 1CEM and Phyre-generated homology models for CohI1, CohI3, and the Cel8A DocI module (15, 19, 24, 35–37). Intermodular linkers were built in PyMOL (36) and defined as flexible in BILBOMD analysis. Individual modules and CohI-DocI interactions were defined as rigid and therefore maintained throughout the analysis. Figures for the ab initio, rigid body, and BILBOMD conformer ensemble models were generated using PyMOL (36). SAXS data are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Structural parameters and molecular mass calculations

|

Rg |

I(0)a | Molecular mass |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guiniera | P(r) | SAXS | DLS | ||

| Å | kDa | ||||

| (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A | |||||

| 16 mg/ml | 61.8 | 62.6 | 341 | 154 | 145 |

| 11 mg/ml | 62.6 | 62.4 | 281 | 153 | 151 |

| 5 mg/ml | 60.3 | 61.1 | 115 | 140 | 132 |

| (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A | |||||

| 3 mg/ml | 63.5 | 66.3 | 78 | 155 | 157 |

| 2 mg/ml | 63.8 | 66.7 | 61 | 149 | 150 |

| 1 mg/ml | 63.3 | 66.3 | 29 | 147 | 126 |

a Determined for q*Rg < 1.3.

RESULTS

Protein Sample Preparation

Two N-terminal fragments of the CipA scaffoldin subunit (CohI1-CohI2 and CohI2-CBM-CohI3) were coexpressed and co-purified with the Cel8A cellulase bearing S458A/S459A mutations in its DocI sequence. These mutations allowed the incorporation of Cel8A onto the CipA CohI-containing fragments in a single DocI orientation, thereby ensuring the homogeneity of complex protein samples for SAXS analysis (14). Typical yields for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes were 20 and 7 mg/liter of Escherichia coli culture, respectively. The purity was judged to be ∼95% based on SDS-PAGE.

DLS was performed on both samples at a range of protein concentrations: 5–16 and 1–3 mg/ml for (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A, respectively. In each case, only a single peak was observed. DLS gave average molecular masses of ∼143 and ∼144 kDa for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes, respectively (Table 1). Both of these values are in agreement with the actual molecular masses of 130.6 kDa for (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and 155.8 kDa for (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A.

Analysis of Raw SAXS Data

SAXS data were recorded for both complexes at a range of different concentrations: 5–16 and 1–3 mg/ml for (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A, respectively (Fig. 2A). All SAXS-determined parameters are summarized in Table 1. The Rg determined from Guinier plots ranged from 60.3 to 62.6 for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex and from 63.3 to 63.8 for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex, which indicates that Rg is independent of concentration for the concentration ranges measured for both complexes. Similarly, Rg calculated using the program GNOM also displayed a narrow range: 61.1–62.6 for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex and 63.3–63.7 for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex, which also supports the concentration-independent behavior of Rg for the two complexes studied. Moreover, the Guinier-derived Rg is in good agreement with that determined using GNOM for both complexes. The molecular masses of both complexes were calculated using the method developed by Fischer et al. (31). The SAXS-determined molecular masses ranged from 140 to 154 kDa for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex and from 147 to 155 kDa for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex, consistent with the monomeric molecular mass of each complex. Furthermore, the pair distribution functions (P(r)), also calculated using GNOM, are skewed to the right for both complexes, which is indicative of elongated molecules (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

SAXS data and analysis of the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A (left panels) and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A (right panels) complexes. A, SAXS data (black) and minimal ensemble search fit (red). B, Guinier plots shown for q*Rg < 1.3. C, pair distribution function. The results indicate that both complexes are monomeric and elongated in solution.

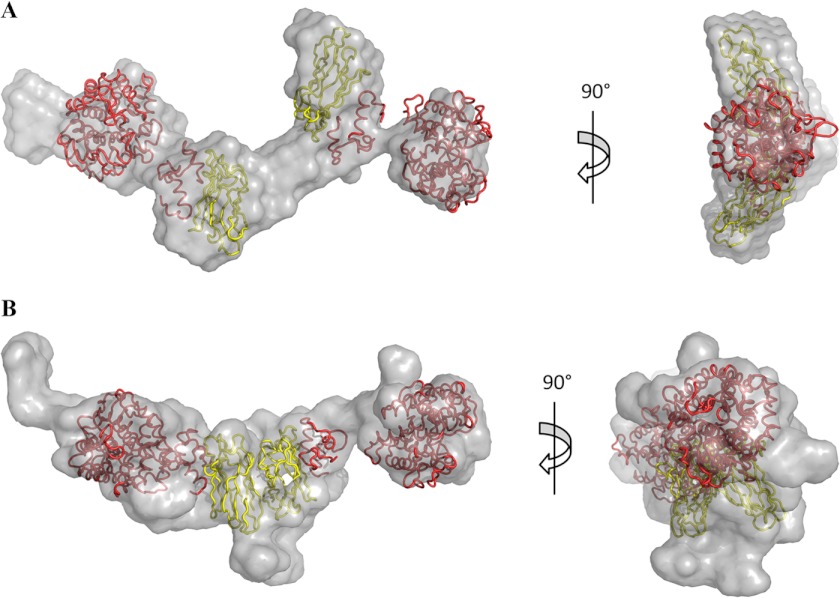

Ab Initio Modeling of Cellulosomal Fragments

The overall shapes of both the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes were calculated using DAMMIN and GASBOR (32, 33). Six envelopes were generated for each complex using both algorithms (supplemental Figs. S1–S4). The best fit envelope in each case, selected based on their exhibiting the lowest χ2 value to the experimental curve, displays elongated conformations consistent with their respective P(r) functions (Figs. 3 and 4). Each of the envelopes contains globular regions that correspond to the GH8 catalytic subunits, the CohI-DocI pairs, and, in the case of the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex, the family 3a CBM. Narrower regions represent the intermodular linker regions. In addition, the GASBOR best fit structure for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex contains small extensions protruding from one of the terminal domains. These extensions are not seen in the DAMMIN-derived structures for this complex and are not present in all of the GASBOR-derived structures. The crystal structures of the GH8 catalytic module, the family 3a CBM, and the CohI·DocI complexes were manually placed within the best fit envelopes to gain further insight into the relative positioning of these modules. With only three exceptions, the x-ray crystal structures fit within the envelopes in close proximity to their neighboring modules. In the DAMMIN-calculated ab initio envelopes, there is a separation of 42 Å between the two CohI modules of the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex, and one of the GH8 modules of the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex is separated from its DocI module by 35 Å. Similarly, one of the GH8 modules of the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex is separated from its DocI module by 28 Å in the GASBOR-determined structure.

FIGURE 3.

Best fit ab initio envelopes for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex. Envelopes generated by DAMMIN (A) and GASBOR (B) are displayed in translucent light gray. CipA CohI and CBMs are colored yellow and dark gray, respectively. Both the DocI and catalytic modules of the Cel8A enzymes are shown in red.

FIGURE 4.

Best fit ab initio envelopes for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex. Envelopes generated by DAMMIN (A) and GASBOR (B) are displayed in translucent light gray. CipA CohI and CBMs are colored yellow and dark gray, respectively. Both the DocI and catalytic modules of the Cel8A enzymes are shown in red.

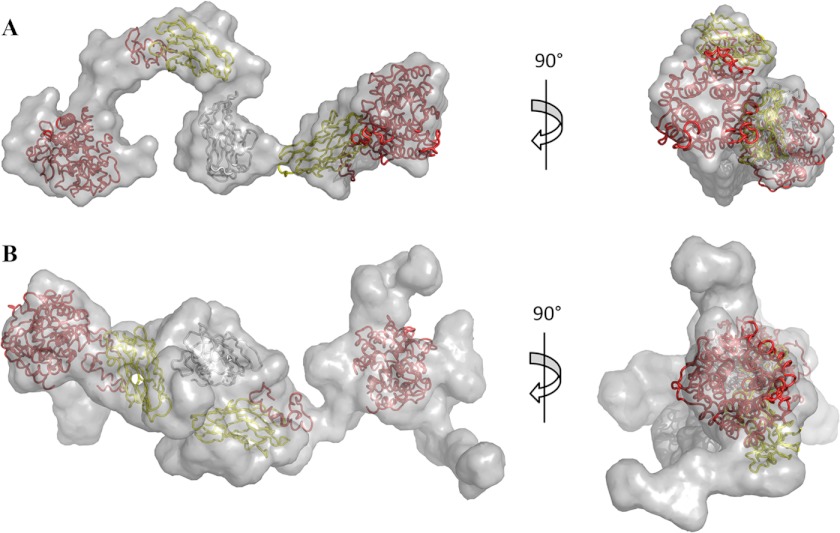

Rigid Body Modeling of Cellulosomal Fragments

Although x-ray crystal structures are not available for intact (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes, crystal structures have been determined for CohI2, CBM, and the Cel8A catalytic module (14, 15, 19, 35). Moreover, the high degree of sequence similarity (>85%) shared between the CohI-DocI-interacting modules in these complexes and those that have previously been solved allowed us to model these with confidence using structural homology modeling techniques. Given the wealth of structural detail available, we decided to combine this with our solution scattering data to provide a better picture of the modular spatial orientation in solution, similar to the method previously used for engineered minicellulosome chimeric complexes (38, 39). BILBOMD is a program designed to investigate flexibility in proteins by building a pool of conformers sampling the conformational space available to the molecule of interest and then selecting those conformations that best fit the experimental solution scattering data (34). Intermodular linkers were built in PyMOL (36) and defined as flexible in subsequent analysis with BILBOMD. Individual modules and CohI-DocI interactions were defined as rigid and therefore maintained throughout the analysis. Large Rg ranges, 43–83 for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex and 51–91 for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A, were initially selected to thoroughly explore all conformations that were available. However, in both cases, BILBOMD returned conformers from a narrower Rg range, 49–79 for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex and 47–80 for the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A, which suggests a physical restraint on the size of both complexes in solution. The best fit conformers for the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes had Rg values of 55 and 56 and fit the experimental data with χ2 values of 2.3 and 3.2, respectively (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Rigid body models of the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A (A) and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A (B) complexes. The protein structures are colored as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

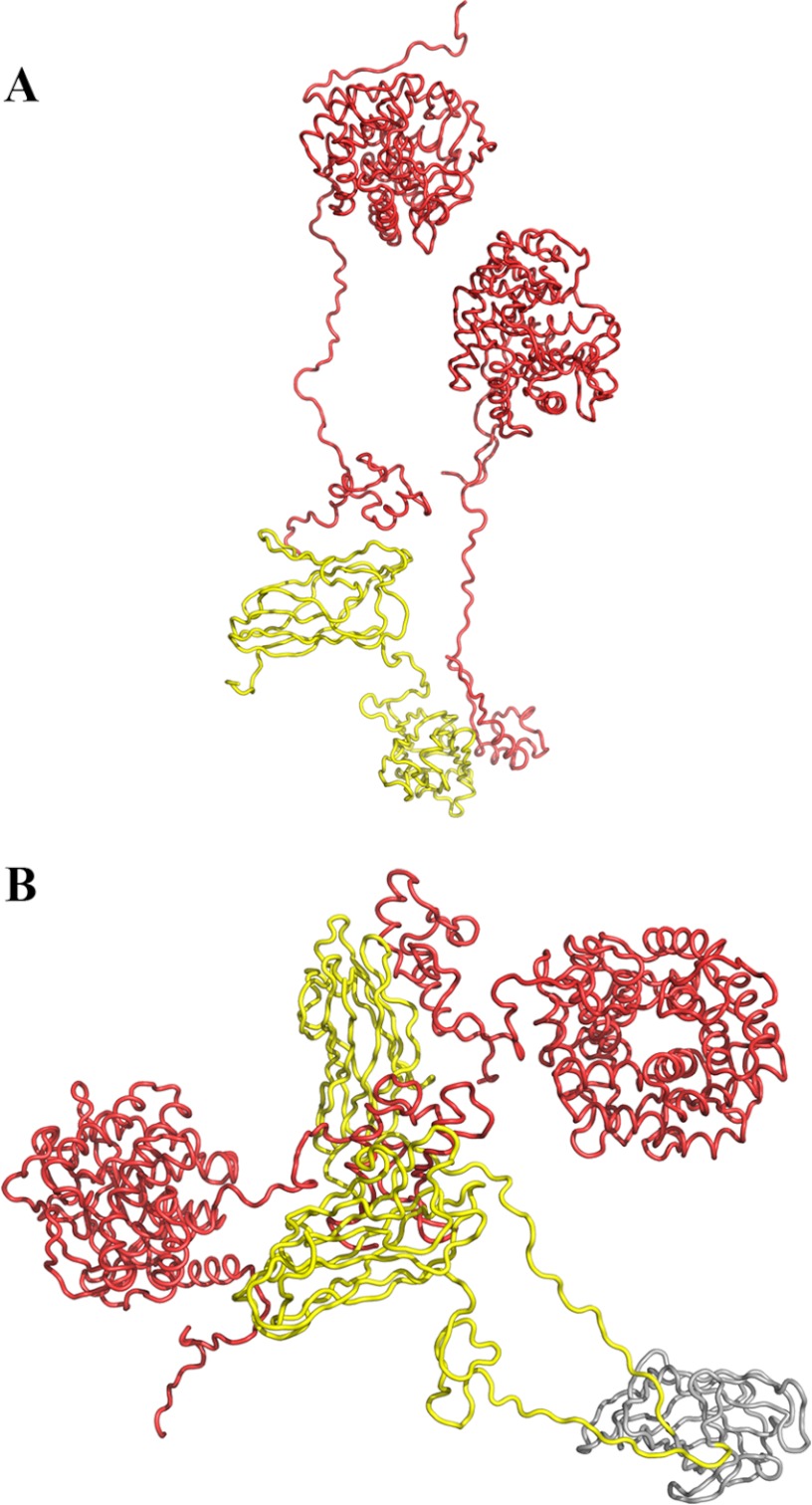

Modular Arrangement and Linker Flexibility

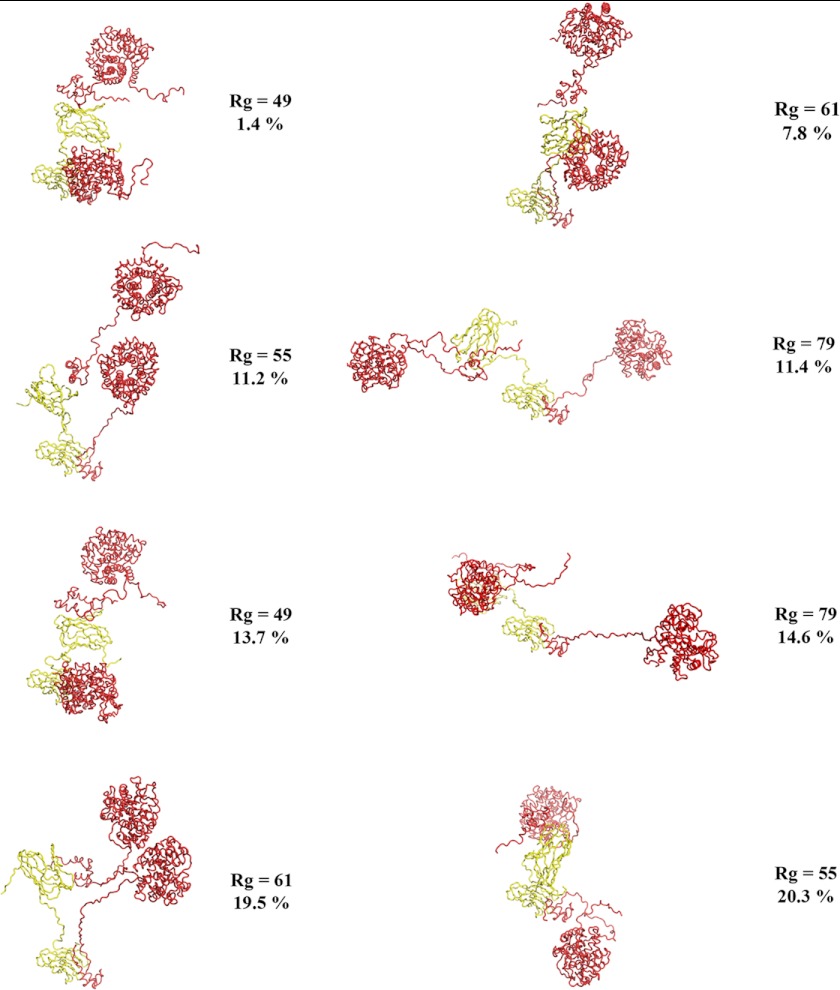

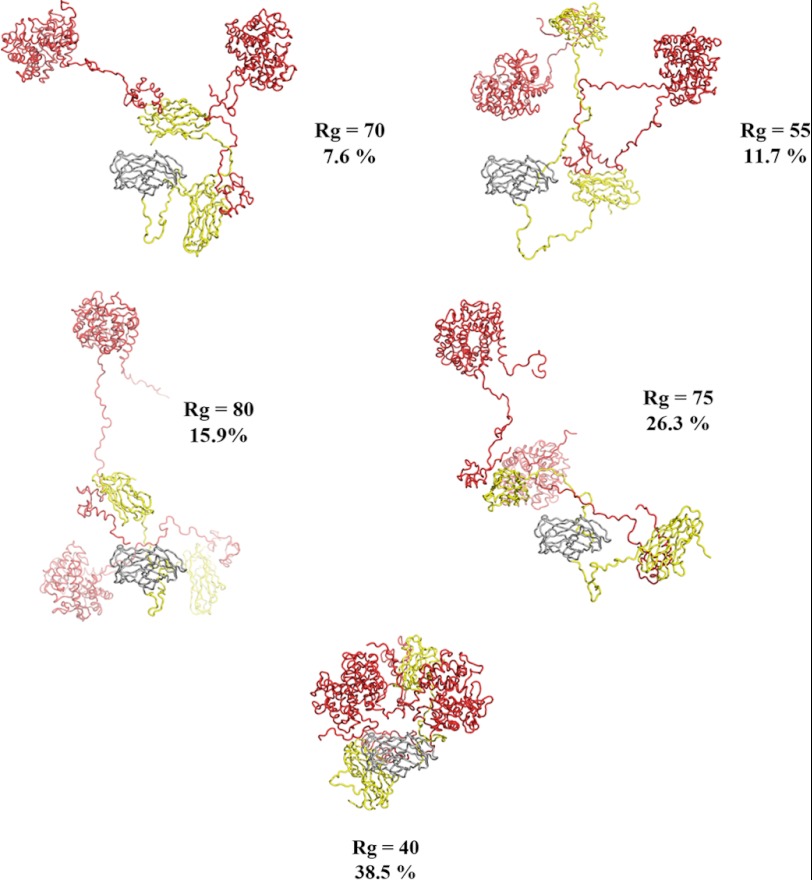

Given the presence of elongated unstructured linkers in the best fit models of both complexes, we investigated whether a small ensemble of conformers would better fit the data. Using a minimal ensemble search (34), we found that both complexes were better fit by an ensemble than the single best fit models. The (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A minimal ensemble is composed of eight conformers: two conformers with Rg of 79 (11.4 and 14.6% of the minimal ensemble), two with Rg of 61 (19.5 and 7.8%), two with Rg of 55 (20.3 and 11.2%), and two with Rg of 49 (1.4 and 13.7%) (Fig. 6). The minimal ensemble for (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A comprised five conformers with Rg of 80 (6.4%), 77 (27.6%), 74 (14.7%), 71 (1.4%), and 47 (49.8%) (Fig. 7). The minimal ensemble improves the fit from the best fit conformation for both the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex (χ2 = 1.3 from χ2 = 2.3) and the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex (χ2 = 2.9 from χ2 = 3.2).

FIGURE 6.

The (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A minimal ensemble. The protein structures are colored as described in the legend to Fig. 3. All eight conformers are displayed. The percentages represent the fraction of a given conformer in the minimal ensemble. A highly dynamic complex with no conformational preferences is revealed.

FIGURE 7.

The (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A minimal ensemble. The protein structures are colored as described in the legend to Fig. 3. All five conformers are displayed. The percentages represent the fraction of a given conformer in the minimal ensemble. Consistent with the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A complex, the (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complex is also highly dynamic with no conformational preferences.

DISCUSSION

The cellulosome is the paradigm of bacterial cellulose degradation. However, despite the wealth of structural information available for well structured cellulosome modules (19–25, 35), the mechanism of its synergy remains enigmatic. In this study, we employed SAXS to build on the limited knowledge of the modular architecture and dynamics of the cellulosome from C. thermocellum. We uncovered structural features of the N terminus of the cellulosome through the study of the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes. We found that both complexes are highly dynamic, lack inter-scaffoldin interactions, and inhabit various compact and extended conformations without preference. The N-terminal portion of the CipA scaffoldin subunit bears the sole substrate recognition module. Therefore, this behavior may be attributed to its unique role within the complex. A more dynamic and open structure would allow greater access to substrate.

The first SAXS study of the cellulosome explored the solution structure of the Clostridium cellulolyticum enzyme Cel48F both alone and bound to a CohI module (38). These experiments were performed with both the native DocI and CohI modules from C. cellulolyticum and the Cel48F enzyme appended to a C. thermocellum DocI module both alone and bound to a C. thermocellum CohI module. In each case, the authors observed more compact and less flexible structures when the enzyme was in complex with a CohI module. Interestingly, we observed Cel8A catalytic modules at variable distances from their cognate DocI modules when bound to CohI modules in both the ab initio envelopes and rigid body models. It should be taken into account that the linker segment of C. cellulolyticum Cel48F is relatively short (∼6 residues) versus that of C. thermocellum Cel8A (∼24 residues). In any event, the excellent agreement between the two independent models likely reflects the dynamic nature of the linker in order for the catalytic module to maximize its ability to reach its substrate. Furthermore, our ensemble analysis confirmed that our observations in the static ab initio and rigid body models are the result of flexibility in the enzyme-borne linkers.

SAXS has also been used to investigate the dynamics of inter-CohI linkers in the context of chimeric scaffoldins composed of a CohI module from C. thermocellum and another from C. cellulolyticum joined by linkers of various lengths and compositions (26). Few or no intermodular contacts and dynamic inter-cohesin linkers in the enzyme-free state were reported. Our work has expanded on this study by evaluating the dynamics in not only two additional types of cellulosomal linkers, CohI-CBM and DocI-GH8, but also in intact natural minicellulosome complexes. Species-specific CohI-DocI interactions are well documented in natural cellulosome systems (e.g. C. cellulolyticum CohI does not interact with C. thermocellum DocI), and recent work suggests that weak intermodular interactions may also play a role in higher order cellulosome structure (40, 41). However, due to the chimeric nature of the scaffoldins analyzed in previous SAXS studies (38, 39), any species-specific interactions would be lost. The results from our work indicate that the N terminus of the C. thermocellum cellulosome is devoid of intermodular interactions, thus ensuring maximal flexibility and, as a result, greater accessibility of the family 3a CBM to its substrate.

Structural studies of fragments of the native C. thermocellum cellulosome suggest that the cellulosome, although flexible, may prefer certain modular arrangements. Cryo-EM analysis of (CohI3-CohI4-CohI5)·3Cel8A revealed a compact structure, with enzymes projected outward in opposite directions (29). Although the intermodular linkers accommodated dynamic elongated conformations as well, these were a minor component of the conformer pool. By contrast, we have demonstrated that both the (CohI1-CohI2)·2Cel8A and (CohI2-CBM-CohI3)·2Cel8A complexes exhibit no preference for compact or elongated conformations. However, due to differences in sample preparation and structural methods, our findings cannot be directly compared with the cryo-EM analysis of the (CohI3-CohI4-CohI5)·3Cel8A complex. As a result, more work will be needed to address the possibility of potential dynamic differences along the CipA scaffoldin.

Interestingly, the high degree of dynamics observed in the complexes studied here indicates that the DocI orientation would have little to no effect on enzyme position in the N terminus of the cellulosome. Therefore, the DocI dual binding mode likely contributes little to the function of the N terminus of the cellulosome. However, regions where more compact conformations predominate may benefit more from precise enzyme orientations.

The work described here has identified key structural and dynamic attributes of the cellulosome N terminus. These characteristics potentially contribute to the function of this distinct region of the cellulosome. Although more work is required to delineate the significance of these conformational preferences in cellulosome function, these findings provide the foundation for optimizing the next generation of designer cellulosomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. M. Hammel for expert assistance in the SAXS studies.

This work was supported by research grants from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to S. P. S.) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to Z. J.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- DocI

- type I dockerin

- CohII

- type II cohesin

- CBM

- carbohydrate-binding module

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- DLS

- dynamic light scattering.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brett C. T., Waldren K. (1996) Physiology and Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls: Topics in Plant Functional Biology, 2nd Ed., Chapman & Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- 2. Himmel M. E., Bayer E. A. (2009) Lignocellulose conversion to biofuels: current challenges, global perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 316–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jordan D. B., Bowman M. J., Braker J. D., Dien B. S., Hector R. E., Lee C. C., Mertens J. A., Wagschal K. (2012) Plant cell walls to ethanol. Biochem. J. 442, 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warren R. A. (1996) Microbial hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50, 183–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bayer E. A., Belaich J. P., Shoham Y., Lamed R. (2004) The cellulosomes: multienzyme machines for degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 521–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bayer E. A., Shimon L. J., Shoham Y., Lamed R. (1998) Cellulosomes–structure and ultrastructure. J. Struct. Biol. 124, 221–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doi R. H., Kosugi A. (2004) Cellulosomes: plant-cell-wall-degrading enzyme complexes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 541–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fontes C. M., Gilbert H. J. (2010) Cellulosomes: highly efficient nanomachines designed to deconstruct plant cell wall complex carbohydrates. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 655–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilbert H. J. (2007) Cellulosomes: microbial nanomachines that display plasticity in quaternary structure. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 1568–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bayer E. A., Morag E., Lamed R. (1994) The cellulosome–a treasure-trove for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 12, 379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Béguin P., Alzari P. M. (1998) The cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 26, 178–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lamed R., Setter E., Kenig R., Bayer E. A. (1983) The cellulosome: a discrete cell surface organelle of Clostridium thermocellum which exhibits separate antigenic, cellulose-binding and various cellulolytic activities. Biotechnol. Bioeng. Symp. 13, 163–181 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lamed R., Setter E., Bayer E. A. (1983) Characterization of a cellulose-binding, cellulase-containing complex in Clostridium thermocellum. J. Bacteriol. 156, 828–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carvalho A. L., Dias F. M., Nagy T., Prates J. A., Proctor M. R., Smith N., Bayer E. A., Davies G. J., Ferreira L. M., Romão M. J., Fontes C. M., Gilbert H. J. (2007) Evidence for a dual binding mode of dockerin modules to cohesins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3089–3094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carvalho A. L., Dias F. M., Prates J. A., Nagy T., Gilbert H. J., Davies G. J., Ferreira L. M., Romão M. J., Fontes C. M. (2003) Cellulosome assembly revealed by the crystal structure of the cohesin-dockerin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13809–13814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerngross U. T., Romaniec M. P., Kobayashi T., Huskisson N. S., Demain A. L. (1993) Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal SL-protein reveals an unusual degree of internal homology. Mol. Microbiol. 8, 325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poole D. M., Morag E., Lamed R., Bayer E. A., Hazlewood G. P., Gilbert H. J. (1992) Identification of the cellulose-binding domain of the cellulosome subunit S1 from Clostridium thermocellum YS. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 78, 181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schaeffer F., Matuschek M., Guglielmi G., Miras I., Alzari P. M., Béguin P. (2002) Duplicated dockerin subdomains of Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD bind to a cohesin domain of the scaffolding protein CipA with distinct thermodynamic parameters and a negative cooperativity. Biochemistry 41, 2106–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tormo J., Lamed R., Chirino A. J., Morag E., Bayer E. A., Shoham Y., Steitz T. A. (1996) Crystal structure of a bacterial family-III cellulose-binding domain: a general mechanism for attachment to cellulose. EMBO J. 15, 5739–5751 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Correia M. A., Prates J. A., Brás J., Fontes C. M., Newman J. A., Lewis R. J., Gilbert H. J., Flint J. E. (2008) Crystal structure of a cellulosomal family 3 carbohydrate esterase from Clostridium thermocellum provides insights into the mechanism of substrate recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 379, 64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guimarães B. G., Souchon H., Lytle B. L., Wu J. H. D., Alzari P. M. (2002) The crystal structure and catalytic mechanism of cellobiohydrolase CelS, the major enzymatic component of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. J. Mol. Biol. 320, 587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kitago Y., Karita S., Watanabe N., Kamiya M., Aizawa T., Sakka K., Tanaka I. (2007) Crystal structure of Cel44A, a glycoside hydrolase family 44 endoglucanase from Clostridium thermocellum. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35703–35711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lytle B. L., Volkman B. F., Westler W. M., Heckman M. P., Wu J. H. (2001) Solution structure of a type I dockerin domain, a novel prokaryotic, extracellular calcium-binding domain. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 745–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shimon L. J., Bayer E. A., Morag E., Lamed R., Yaron S., Shoham Y., Frolow F. (1997) A cohesin domain from Clostridium thermocellum: the crystal structure provides new insights into cellulosome assembly. Structure 5, 381–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tavares G. A., Béguin P., Alzari P. M. (1997) The crystal structure of a type I cohesin domain at 1.7 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 273, 701–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Molinier A. L., Nouailler M., Valette O., Tardif C., Receveur-Bréchot V., Fierobe H. P. (2011) Synergy, structure and conformational flexibility of hybrid cellulosomes displaying various inter-cohesin linkers. J. Mol. Biol. 405, 143–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bayer E. A., Lamed R. (1986) Ultrastructure of the cell surface cellulosome of Clostridium thermocellum and its interaction with cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 167, 828–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mayer F., Coughlan M. P., Mori Y., Ljungdahl L. G. (1987) Macromolecular organization of the cellulolytic enzyme complex of Clostridium thermocellum as revealed by electron microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53, 2785–2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. García-Alvarez B., Melero R., Dias F. M., Prates J. A., Fontes C. M., Smith S. P., Romão M. J., Carvalho A. L., Llorca O. (2011) Molecular architecture and structural transitions of a Clostridium thermocellum mini-cellulosome. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 571–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guinier A. F., Fournet F. (1955) Small Angle X-rays, Wiley Interscience, New York [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fischer H., de Oliveira Neto M., Napolitano H. B., Polikarpov I., Craievich A. F. (2010) The molecular weight of proteins in solution can be determined from a single SAXS measurement on a relative scale. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 101–109 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Svergun D. I. (1999) Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys. J. 76, 2879–2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Svergun D. I., Petoukhov M. V., Koch M. H. (2001) Determination of domain structure of proteins from x-ray solution scattering. Biophys. J. 80, 2946–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pelikan M., Hura G. L., Hammel M. (2009) Structure and flexibility within proteins as identified through small angle X-ray scattering. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 28, 174–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alzari P. M., Souchon H., Dominguez R. (1996) The crystal structure of endoglucanase CelA, a family 8 glycosyl hydrolase from Clostridium thermocellum. Structure 4, 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kelley L. A., Sternberg M. J. (2009) Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hammel M., Fierobe H. P., Czjzek M., Finet S., Receveur-Bréchot V. (2004) Structural insights into the mechanism of formation of cellulosomes probed by small angle x-ray scattering. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55985–55994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hammel M., Fierobe H. P., Czjzek M., Kurkal V., Smith J. C., Bayer E. A., Finet S., Receveur-Bréchot V. (2005) Structural basis of cellulosome efficiency explored by small angle x-ray scattering. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38562–38568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Adams J. J., Currie M. A., Ali S., Bayer E. A., Jia Z., Smith S. P. (2010) Insights into higher-order organization of the cellulosome revealed by a dissect-and-build approach: crystal structure of interacting Clostridium thermocellum multimodular components. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 833–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Currie M. A., Adams J. J., Faucher F., Bayer E. A., Jia Z., Smith S. P. (2012) Scaffoldin conformation and dynamics revealed by a ternary complex from the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26953–26961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]