Abstract

We report a rare case of the concurrent manifestation of central diabetes insipidus (CDI) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). A 56 year-old man was diagnosed as a type 2 DM on the basis of hyperglycemia with polyuria and polydipsia at a local clinic two months ago and started an oral hypoglycemic medication, but resulted in no symptomatic improvement at all. Upon admission to the university hospital, the patient's initial fasting blood sugar level was 140 mg/dL, and he showed polydipsic and polyuric conditions more than 8 L urine/day. Despite the hyperglycemia controlled with metformin and diet, his symptoms persisted. Further investigations including water deprivation test confirmed the coexisting CDI of unknown origin, and the patient's symptoms including an intense thirst were markedly improved by desmopressin nasal spray (10 µg/day). The possibility of a common origin of CDI and type 2 DM is raised in a review of the few relevant adult cases in the literature.

Keywords: Polyuria, Central diabetes insipidus, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Water deprivation test

Introduction

Once the primary polydipsia, mostly due to psychogenic polydipsia, is excluded from the causes of polyuria, either water diuresis by diabetes insipidus (DI) or osmotic diuresis by diabetes mellitus (DM) could be considered for its differential diagnoses1).

The coexistence of DI and DM in the same patient has been rarely reported in Wolfram syndrome (known as DIDMOAD) as a congenital genetic disorder in pediatric age group, which has the concurrent association of central diabetes insipidus (CDI) with type 1 DM accompanied by optic atrophy, deafness, and infantilism2). The coexistence of CDI and type 2 DM has been noted in less than 10 adult patients, most of whom had 2 to 15 years history of type 2 DM before developing CDI3-6). An exception was a patient with Klinefelter's syndrome who had CDI for more than 5 years before presenting with hyperosmolar coma due to type 2 DM7). Herein, we report a unique case of the simultaneous development of CDI and type 2 DM in the same patient.

Case

A 56-year-old man was admitted to the renal unit of the tertiary university hospital with symptoms of polyuria with nocturia, and polydipsia with severe thirst for the past 2 months. Initially, the patient visited a local clinic and was diagnosed as type 2 DM with a fasting blood sugar, 150mg/dL. Despite being controlled hyperglycemia with an oral hypoglycemic agent, he continued drinking daily more than 8 L of cold water (about 10 bottles of refrigerated water, 750 ml capacity) and passed large amounts of urine frequently. He had no specific history including head trauma or mental disorder, and denied any pertinent family history. The patient showed no signs of systemic illness such as fever or arthralgia, or neurologic symptoms involving the central nervous system. He has been working as a gardener with 176 cm in height and 68 kg in weight (71 kg before this event). The physical examination was unremarkable with blood pressure of 132/70 mmHg, pulse rate of 80/min, respiratory rate of 16/min, and temperature of 36.8℃. In the laboratory findings, his white blood cell count was 9,700/mm3; hemoglobin, 13.4 g/dL; platelet, 376×103/mm3; sodium, 140 mEq/L; potassium, 3.8 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 12 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.0 mg/dL and osmolality 295 mOsm/kg water. HbA1c was 7.2% and post-prandial glucose was checked around 180mg/dl with fasting blood sugar of 140 mg/dL. In urine analysis, the urine pH was 6.0; specific gravity 1.006; albumin (-); glucose (-); WBC 0-4/HPF; RBC 0-2/HPF, and osmolality 140mOsm/kg water. Fluid intake and output in 24 hours recorded 9 L in oral water intake from water containers and 11.7 L in urine output. In hormone assays, ACTH was 25.2 pg/mL (reference value, 6.0-76.0 pg/mL), prolactin 8 µg/L (reference value, 0-15 µg/L), cortisol 9.8 µg/dL (referencel value, 5-25 µg/dL), hGH 2.26 ng/mL (reference value, 0.5-17 ng/mL), and TSH 0.99 µU/mL (reference value, 0.5-4.7 µU/mL). Also, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) activity was within normal range (reference value, <40 U/L).

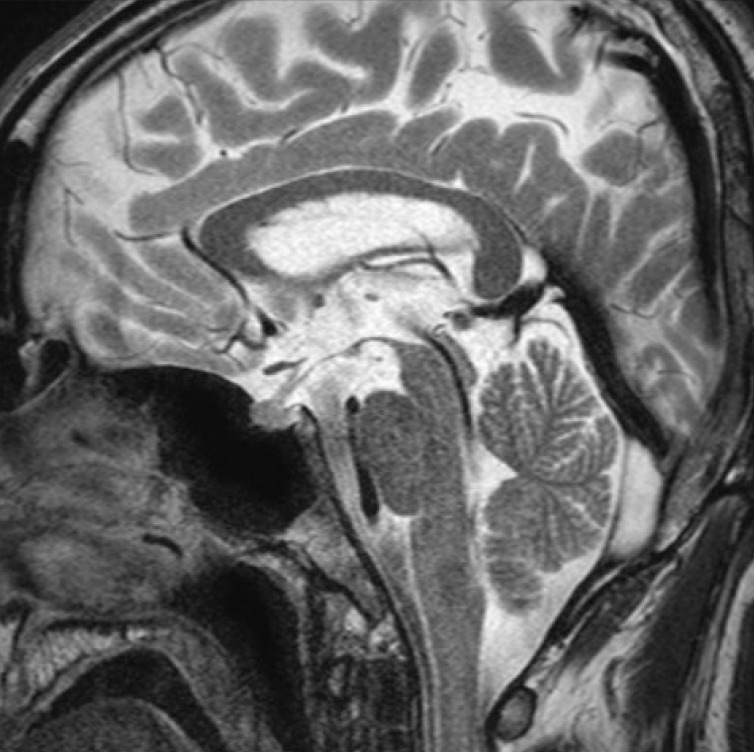

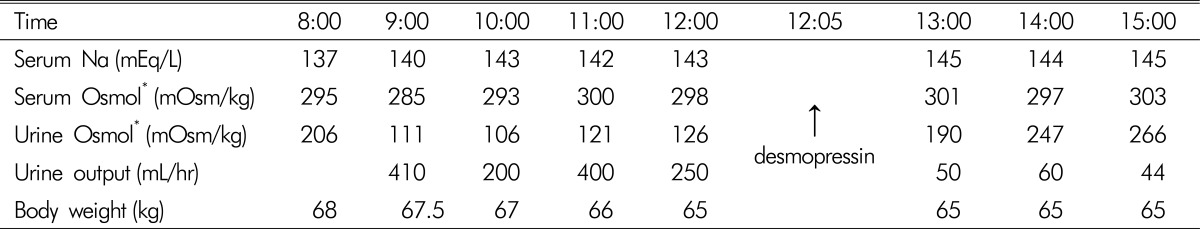

On hospital day 5, the patient underwent a water deprivation test according to the method of Miller-Moses test8) because of persistent polydipsia and polyuria despite blood glucose control. The results are shown in Table 1. During dehydration, the patient lost 3kg (4.4% of body weight), and urine osmolality remained hypotonic below 130 mOsm/kg. Basal ADH level was 5.18 pg/dL, and the repeat ADH level following the stimulation by water deprivation was 3.95 pg/dL, which revealed no increment despite the increased serum osmolality up to 300 mOsm/kg from the baseline levels of 285 to 295 mOsm/kg. One puff (5 µg) of desmopressin nasal spray resulted in the increase of urine osmolality to 266 mOsm/kg (>100% increase from the baseline level, 126 mOsm/kg) and in the marked reduction of urine output from 200-410 ml/hr to 44-60 ml/hr. These results were compatible with CDI1,8), whose causes would be mostly idiopathic because of normal findings in hypothalamus and hypophysis in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of sella (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Results of water deprivation test

Fig. 1.

Sagittal dynamic MR images in our patient showing normal enhancement pattern of the straight sinus and of the posterior pituitary.

On discharge (hospital day 9), the dose of desmopressin nasal spray (minirin nasal spray®) was adjusted to 1 puff per 12 hrs (10 µg/day), and urine output was markedly reduced to below 2-3 L/day with no more intense thirst. Also, DM was controlled with fasting blood sugar below 115 mg/dL by metformin (novamet GR® 500mg bid) and American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended diet.

Discussion

In this case study, the persistence of polyuria and polydipsia for 2 months despite the absence of evidence of osmotic diuresis, along with the recently discovered type 2 DM, led to a diagnosis of coexisting DI and DM. Because most of the patients with DI have intact thirst mechanisms, they do not present with hyperosmolality or hypernatremia. In those cases, water deprivation test is useful for differential diagnosis of polyuria. Following water deprivation in the present case, urine osmolality was unchanged and remained hypotonic, less than a half of the increased serum osmolality up to 300 mOsm/kg. Also, there was more than 100% increase in urine osmolality after administrating desmopressin and thus markedly decreased urine volume (Table 1). That is compatible with CDI according to the criteria of Miller-Moses test8).

The causes of CDI are various including neoplastic lesion, infection, inflammation, trauma, autoimmune disease with directly or indirectly affecting hypothalamus or pituitary. However, idiopathic causes have been noted up to 50% of CDI patients, since the causes remain unidentified at the time of its diagnosis as was in our case9,10). However, along with advanced imaging techniques in the brain, the portion of idiopathic CDI has gradually been decreased with more identified evidences from the underlying causes of CDI such as other constitutional or organic disorders including abnormal blood supply to either hypothalamus or pituitary gland11). Therefore, long-term follow-up with periodic MRI examinations, if necessary, are recommended to the idiopathic CDI patients for the unrecognized causes at the time of diagnosis12).

In our case, both CDI and type 2 DM were diagnosed almost at the same time. The relationship between DM and the carbohydrate metabolism of central nervous system has not been clarified as yet. Therefore, it would be more difficult to find the pathogenetic causes of coexistent CDI with DM, except for Wolfram syndrome as a congenital genetic disorder presented with type 1 DM, CDI, optic atrophy, and deafness known as DIDMOAD mnemonically2). In Wolfram syndrome with the defective wolframin protein expression by the mutation of the WFS1 gene as a neurodegenerative autosomal recessive disorder, coexistent CDI and type 1 DM developed the loss of neurons from paraventricular nuclei and supraoptic nuclei in the hypothalamus and the loss of insulin-producing pancreatic islet cells. However, it is still unidentified as yet that type 1 DM is primarily due to pancreatic islet cell loss or a secondary one from an unidentified central neuropathologic defect13).

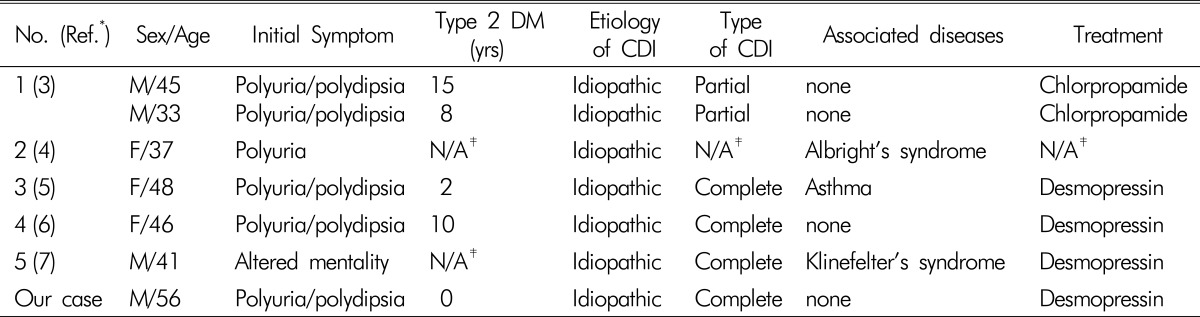

However, through the experience with this case of the unique presentation of simultaneous manifestation of both type 2 DM and CDI, a single pathogenetic disorder, either genetic like Albright's hereditary osteodystrophy-like syndrome4) or sporadic, might be considered as plausible causes for the coexistence of these two different diseases rather than attributing to incidental or fortuitous findings. In a review of the literature, we found only 6 cases of coexistence of the two disorders (Table 2). Almost all the coexisting cases of both type 2 DM and CDI revealed the time interval between type 2 DM and CDI when in diagnosis each other; not presented at the same time as was in our case. In one of these rare case reports, 2 adult male siblings were found to have had the coexisting CDI and DM suggested as a familial disease representing a single genetic abnormality3). In another case report, a 41 year-old man with a 5-year history of CDI presented with hyperosmolar coma due to type 2 DM, which led to the diagnosis of Klinefelter's syndrome known as a sex chromosome anomaly with hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism7). We suggest, therefore, that the several instances of coexistence of type 2 DM and CDI warrant further efforts to identify a unifying pathogenic mechanism for these two different clinical diseases.

Table 2.

Cases of co-existing central diabetes insipidus (CDI) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) in the literature

After reviewing the concerned literature, we could conclude that almost all the coexisting cases of both type 2 DM and CDI revealed the time interval between type 2 DM and CDI when in diagnosis each other; not presented at the same time as was in our case. In another case report, a 41 yr-old man with preexisting history of CDI was presented with hyperosmolar coma due to type 2 DM, Therefore, we suggest that the coexistence of type 2 DM and CDI as was in our case, warrants a further vigilant follow-up investigation to look for a unifying pathogenic mechanism for these two different clinical diseases.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, this case would be the first case of coexistence of CDI and type 2 DM in which the two diseases manifested at the same time. Although it is not yet clear whether they had a common cause, it reminds us to be aware of the possible coexistence of CDI, when diabetic patients encounter with the persistent polyuria and polydipsia despite its proper management.

References

- 1.Barry M. Benner and rector's the kidney. 8th ed. Philadelphia: WN saunders; 2008. Disorder of insufficient arginine vasopressin or arginine vasopressin effect; pp. 469–483. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S. Wolfram syndrome: important implications for pediatricians and pediatric endocrinologists. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(1):28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gossain VV, Sugawara M, Hagen GA. Co-existent diabetes mellitus and diabetes mellitus, a familial disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1975;41:1020–1024. doi: 10.1210/jcem-41-6-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulose KP, Padmakumar N. Diabetes insipidus in a patient with diabetes mellitus. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:1176–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akarsu E, Buyukhatipoglu H, Aktaran S, Geyik R. The value of urine specific gravity in detecting diabetes insipidus in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:C1–C2. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isobe K, Niwa T, Ohkubo M, Ohba M, Shikano M, Watanabe Y. Klinefelter's syndrome accompanied by diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus. Intern Med. 1992;31:917–921. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.31.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller MT, Dalakos T, Moses AM, Fellerman H, Streeten DH. Recognition of partial defects in antidiuretic hormone secretion. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:721–729. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-73-5-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maghnie M, Cosi G, Genovese E, et al. Central diabetes insipidus in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:998–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang LC, Cohen ME, Duffner PK. Etiologies of central diabetes insipidus in children. Pediatr Neurol. 1994;11:273–277. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maghnie M, Altobelli M, di Iorgi N, et al. Idiopathic central diabetes insipidus is associated with abnormal blood supply to the posterior pituitary gland caused by vascular impairment of the inferior hypophyseal artery system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1891–1896. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SJ, Lee SY, Shin CH, Yang SW. Clinical, endocrinological and radiological courses in patients who was initially diagnosed as idiopathic central diabetes insipidus. Korean J Pediatr. 2007;50(11):1110–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.d'Annunzio G, Minuto N, D'Amato E, et al. Wolfram syndrome (diabetes insipidus, diabetes, optic atrophy, and deafness) Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1743–1745. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilson JB, Merchant SN, Adams JC, Joseph JT. Wolfram syndrome: a clinicopathologic correlation. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118(3):415–428. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0546-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]