Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Ground glass opacity (GGO) on thin-section computed tomography (CT) has been reported to be a favourable prognostic marker in lung cancer, and the size or area of GGO is commonly used for preoperative evaluation. However, it can sometimes be difficult to evaluate the status of GGO.

METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted on 572 consecutive patients with resected lung cancer of clinical stage IA between 2004 and 2011. All patients underwent preoperative CT and their radiological findings were reviewed. The areas of consolidation and GGO were evaluated for all lung cancers. Lung cancers were divided into three categories on the basis of the status of GGO: GGO, part solid and pure solid. Lung cancers in which it was difficult to measure GGO were selected and their clinicopathological features were investigated.

RESULTS

Seventy-one (12.4%) patients had lung cancer in whom it was difficult to measure GGO. In all these cases, consolidation and GGO were not easily measured because of their scattered distribution. In this cohort, nodal metastases were not observed at all. The frequency of other pathological factors, such as lymphatic and/or vascular invasion, was significantly lower (P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

This new category of lung cancer with scattered consolidation on thin-section CT scan tended to be pathologically less invasive. When lung cancer has GGO and is difficult to measure because of a scattered distribution, its prognosis could be favourable regardless of the area of GGO. This new category could be useful for the preoperative evaluation of lung cancer.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Thoracic surgery, Diagnosis, Lymph node, Ground glass opacity

INTRODUCTION

Small-sized lung cancer tends to be found in screening with computed tomography (CT). CT can detect not only small tumours but also tumours that are faint on chest roentgenogram, such as tumours with ground glass opacity (GGO). GGO on thin-section CT is one of the most favourable prognostic factors in lung cancer. In most previous reports, the size of GGO has been evaluated in one dimension for predicting the prognosis [1–10]. These authors have claimed that the proportion of GGO and consolidation was important for predicting the prognosis, and their findings were confirmed by a prospective multi-institutional trial (JCOG0201) [4]. On the other hand, it is often difficult to measure the dimension of GGO or consolidation. In this study, we investigated the clinicopathological features of lung cancer with a GGO appearance that was difficult to measure on thin-section CT scan to aid in determining the optimal management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A retrospective study was conducted on 1179 patients with primary lung cancer, which was resected between January 2004 and April 2011 at our institute. Among them, 637 patients had clinical stage IA lung cancer, and thin-section CT was available for 572. Clinical stage IA was defined as follows: (1) primary tumor was 3 cm or less in greatest dimension, (2) there was no regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, according to the 7th edition of the Union International Contre le Cancer TNM staging system. Thin-section CT was performed to evaluate the entire lung with collimation of 1–2 mm. The lung was photographed with a window level of −500 to −700 Hounsfield units (HU) and a window width of 1500–2000 HU as a lung window.

Definition of lung cancer with scattered consolidation (LCSC)

All thin-section CT scans were reviewed by 3 of the authors (T.M., K.S. and K.T.), and the following radiological factors were investigated: maximum tumour dimension, maximum dimension of consolidation, distribution of GGO and pleural tail. The ratio of consolidation to tumour size was evaluated. We defined LCSC as follows:

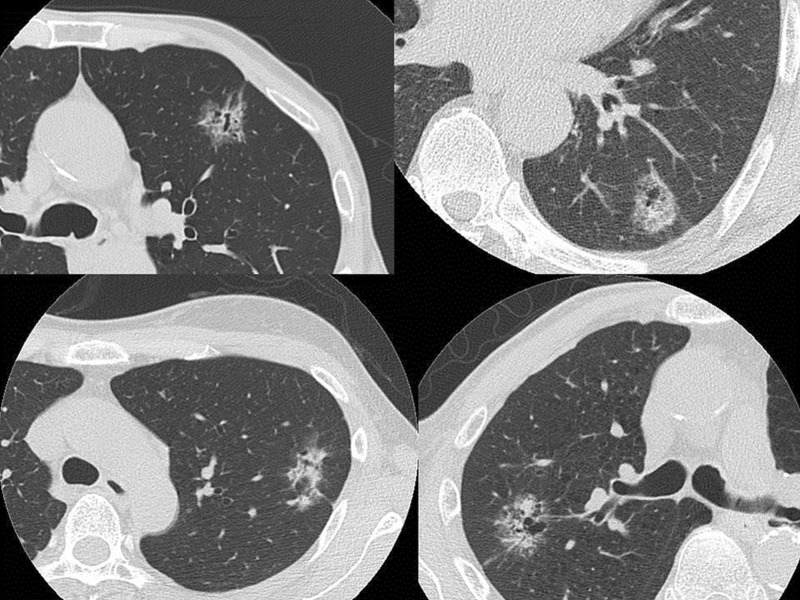

lung cancer with consolidation that is difficult to be measured on thin-section CT scan (Fig. 1),

lung cancer with GGO whose distribution is scattered. In all these cases, consolidation and GGO were not easily measured because of discontinuous consolidation of tumour. So these tumours have more than two parts of consolidation with >1 mm.

We exclude tumours with emphysematous lung because some of these areas of consolidation seem to be discontinuous. We investigated the clinicopathological features of LCSC and compared them with those of other types of lung cancer. We also determined the category to which LCSC had originally belonged. Our classification of GGO consisted of three types: GGO, part solid and pure solid. Conventional classification is based on the findings on thin-section CT scan, i.e. the consolidation/tumour ratio (CTR). The GGO, part solid and pure solid groups were defined as tumour having a CTR of ≤0.5, >0.5 and 1.0, respectively. Finally, we divided all the lung cancers into four categories, i.e. the three conventional categories and the new category of LCSC.

Figure 1:

The proportions of consolidation and ground glass opacity were not easily measured because of their scattered distribution such as in these cases.

Statistical analysis

To compare two factors, the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used. Multivariate analyses were performed by logistic regression analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS.

RESULTS

Characteristics of lung cancer with scattered consolidation

LCSC was observed in 71 (12%) of 572 patients. The clinicopathological features of these patients were compared according to radiological findings (Table 1). There were 29 men and 42 women who ranged in age from 24 to 86 years (median 66 years). Compared with other tumours, the LCSCs were significantly bigger in the maximum tumour dimension. Women tended to have LCSC, and the CTR was ≥0.5 in more than half of the patients with LCSC, but this difference was not statistically significant. All the LCSCs were histologically adenocarcinomas and showed pathological invasiveness, such as nodal metastasis, or lymphatic or vascular invasion, and these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

Table 1:

Clinicopathological features by radiological findings

| Clinicopathological factors | LCSC | Others | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 29 (40.8%) | 247 (49.3%) | 0.1820 |

| Women | 42 (59.2%) | 254 (50.7%) | |

| Age | |||

| Years (median) | 66 (24–86) | 66 (26–89) | 0.4508 |

| Smoking states (pack-year) | |||

| ≥40 | 11 (11.3%) | 113 (23.5%) | 0.2142 |

| <40 | 55 (88.7%) | 368 (76.5%) | |

| CEA (ng/ml) | |||

| ≥5.0 | 7 (10.4%) | 89 (18.1%) | 0.1657 |

| <5.0 | 60 (89.6%) | 402 (81.9%) | |

| Tumour size (mm) | |||

| 20 | 38 (53.5%) | 329 (65.7%) | 0.0458 |

| <20 | 33 (42.5%) | 172 (34.3%) | |

| Visual CTR | |||

| <0.5 | 25 (35.2%) | 126 (25.1%) | 0.0719 |

| ≥0.5 | 46 (64.8%) | 375 (74.9%) | |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 71 (100%) | 430 (85.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Others | 0 (0%) | 71 (14.2%) | |

| Pathological N status | |||

| N0 | 71 (100%) | 424 (84.8%) | <0.0001 |

| N1 or 2 | 0 (0%) | 76 (15.2) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||

| Positive | 12 (16.9%) | 235 (46.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Negative | 59 (83.1%) | 266 (53.1%) | |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| Positive | 5 (7.0%) | 213 (42.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Negative | 66 (93.0%) | 288 (57.5%) | |

aχ2-test or Fisher's exact test.

LCSC: lung cancer with scattered consolidation; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigens; CTR: consolidation tumour ratio.

Relationship between conventional ground glass opacity status and lung cancer with scattered consolidation

The relationships between the three conventional categories and LCSC are shown in Table 2. None of the patients in the pure solid group was categorized as LCSC. LCSC was found in the part solid and GGO groups, significantly more often than in the pure solid group. With regard to pathological invasiveness, the conventional GGO, part solid and pure solid groups showed 0, 5.9 and 25.0% nodal metastasis, respectively (Table 3). For other forms of invasiveness, such as lymphatic or vascular invasion, there were significant relationships between these pathological factors and conventional GGO status.

Table 2:

The relationship between ground glass appearance and lung cancer with scattered consolidation

| Conventional category | LCSC | non-LCSC | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGO group (CTR ≤ 0.5) | 25 (35.2%) | 126 (25.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Part solid group (0.5 < CTR < 1.0) | 46 (64.8%) | 106 (21.2%) | |

| Pure solid group (CTR = 1) | 0 (0%) | 269 (53.7%) |

aFisher's exact test.

GGO: ground glass opacity; CTR: consolidation tumour ratio.

Table 3:

The relationship between conventional categories and p-N status

| Conventional category | p-N1 or 2 | p-N0 | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGO group (CTR ≤ 0.5) | 0 (0%) | 151 (100%) | <0.0001 |

| Part solid group (0.5 < CTR < 1) | 9 (5.9%) | 143 (94.1%) | |

| Pure solid group (CTR = 1) | 67 (25.0%) | 201 (75.0%) |

aFisher's exact test.

GGO: ground glass opacity; CTR: consolidation tumour ratio.

Predictors of pathological invasiveness

In a multivariate analysis for predictors of lymphatic and vascular invasion, the new category LCSC was an independent predictor along with gender, the preoperative serum CEA titer, maximum tumour dimension and CTR (Table 4). LCSC showed pathological invasiveness more often than GGO, but less often than part solid lung cancer. LCSC did not show lymph node metastasis (Table 5).

Table 4:

Results of multivariate analysis for predictors of lymphatic invasion

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCSC (vs non-LCSC) | 0.208 | 0.100–0.433 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (male) | 1.584 | 1.055–2.378 | 0.0264 |

| CEA (≥5 ng/ml) | 3.033 | 1.744–5.274 | <0.0001 |

| Tumour size (>20 mm) | 2.520 | 1.647–3.855 | <0.0001 |

| Visual CTR (≥0.5) | 16.414 | 7.724–34.883 | <0.0001 |

aP-value in logistic regression analysis.

CI: confidence interval; LCSC: lung cancer with scattered consolidation; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigens; CTR: consolidation tumour ratio.

Table 5:

Incidence of nodal metastasis and lymphatic invasion according to a new radiological grouping

| New category | pN | Ly | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGO group (CTR ≤ 0.5) | 0/126 (0%) | 7/126 (5.5%) | <0.0001 |

| LCSC group | 0/71 (0%) | 12/71 (16.9%) | |

| Part solid group (0.5 < CTR < 1) | 9/106 (8.5%) | 41/106 (38.7%) | |

| Pure solid group (CTR = 1) | 67/268 (25.0%) | 187/268 (69.5%) |

aFisher's exact test.

pN: pathological nodal metastasis; Ly: lymphatic invasion; GGO: ground glass opacity; CTR: consolidation tumour ratio; LCSC: lung cancer with scattered consolidation.

DISCUSSION

As CT is used more widely, we increasingly have opportunities to detect small or faint lung nodules that could be diagnosed as lung cancer. Although lobectomy is now a standard operation based on the results of LCSG [11], limited resection such as wide wedge resection or segmentectomy has been studied in many institutions [12–15]. Many surgeons think that limited resection could be equivalent to lobectomy for appropriately selected patients.

Preoperative GGO on thin-section CT has been reported to be a favourable prognostic factor (Table 6) [1–10, 16–18]. The preoperative GGO status is important for selecting patients who are suitable for limited surgical resection [19–22]. While most authors have evaluated GGO in terms of the maximum tumour size and consolidation in one dimension, there is still some controversy regarding the optimal methods for the evaluation of ground glass. It is not uncommon for lung cancers to show GGO that is difficult to measure. Thus, we identified the clinicopathological characteristics of this type of lung cancer.

Table 6:

Meta-analysis on ground glass opacity (GGO) as a prognostic factor for lung cancer

| Authors/year | No. | Cases | Methods | Good prognosis | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jang/1996 [9] | 14 | – | – | Focal area of GGO | Retrospective |

| Suzuki/2000 [7] | 69 | Ad, cIA | CTR | GGO > 0.5 | Retrospective |

| Aoki/2001 [1] | 127 | 3 cm | CTR | GGO > 0.5 | Retrospective |

| Takamochi/2001 [8] | 269 | Ad | TDR | TDR and CEA | Retrospective |

| Kim/2001 [10] | 224 | Ad, cIA | Visual | GGO extent | Retrospective |

| Okada/2003 [3] | 167 | Ad, 3 cm | TDR | TDR > 0.5 | Retrospective |

| Ohde/2003 [2] | 98 | Ad, 2 cm | CTR | GGO > 0.5 | Retrospective |

| Suzuki/2006 [6] | 349 | Ad, 2 cm | CTR | CTR and CEA | Retrospective |

| Suzuki/2011 [4] | 811 | Ad, 3 cm | CTR | CTR < 0.25 | Prospective |

CTR: consolidation tumour ratio; Ad: adenocarcinoma; TDR: tumour shadow disappearance rate.

None of the patients with LCSC was in the pure GGO or pure solid group. There were more women than men in the LCSC group, but this difference was not statistically significant. Generally, men are more likely to have lung cancer, and the observed predominance of women could mean that this type of lung cancer is not related to smoking status or that carcinogenesis could be associated with gender. Tumours in LCSC were significantly larger than those in the other groups (P = 0.0458). LCSC shows atypical radiological findings on thin-section CT, and thus, a preoperative diagnosis could be difficult. This is one of the reasons for the larger size of LCSC. LCSC tends to grow slowly, which makes diagnosis difficult. All the LCSCs were histologically adenocarcinoma, and this is a distinct characteristic of LCSC.

LCSC did not show nodal metastases. LCSC tends to be less invasive pathologically, such as with regard to lymphatic or vascular invasion. One of the most potent prognostic factors is the size or nature of a central fibrosis of adenocarcinoma of the lung [7, 12, 23, 24]. Active fibroblasts in the central fibrosis have been reported to be associated with a poor prognosis [23]. Active fibroblasts are a sign of destruction of the basement membrane by cancer cells, which leads to mesenchymal destruction of the lung. This destruction results in the exclusion of air in the lung. This is a phase of consolidation on CT scan. If the invasion or destruction of the mesenchyme of the lung is minimal, air in the lung remains within the lung cancer, resulting in a ground glass appearance on thin-section CT. Thus, consolidation on thin-section CT could be strongly associated with the invasiveness of lung cancer [4]. According to the above considerations, LCSC has no pure consolidation and its pathological invasiveness should be minimal. When LCSC grows, it should show pure consolidation and could metastasize to nodes and distant organs. So an early diagnosis is necessary.

LCSC is a new radiological entity for lung cancer. This category is included mainly in the part-solid group. It is difficult to measure the size of consolidation for LCSC, which makes classification of this tumour vague. Similar radiological findings for lung cancer have been reported as part-solid groups [6]. However, this is the first report to focus on this category of lung cancer. JCOG0201 defined peripheral early lung cancer to be lung cancer of ≤2.0 cm in size in which consolidation is less than one fourth of the maximum tumour dimension [4]. Most of these lesions could be cured with limited surgical resection [13–15, 25]. LCSC should also be curable by limited surgical resection, although a clinical trial is needed to support this supposition. This study was limited in that it was a retrospective study in a single institute and the sample size was small. Thus, we are planning to perform a prospective multicentre trial in the near future to collect more patients with lung cancer having scattered consolidation.

In conclusion, the new category lung cancer with scattered consolidation has been proposed, and recognition of this category could resolve the problem of misclassification of lung cancer with difficult-to-measure consolidation on thin-section CT. Limited surgical resection may be the preferred option for lung cancers in this category in the near future.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki T, Tomoda Y, Watanabe H, Nakata H, Kasai T, Hashimoto H, et al. Peripheral lung adenocarcinoma: correlation of thin-section CT findings with histologic prognostic factors and survival. Radiology. 2001;220:803–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2203001701. doi:10.1148/radiol.2203001701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohde Y, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Takahashi K, Suzuki K, et al. The proportion of consolidation to ground-glass opacity on high resolution CT is a good predictor for distinguishing the population of non-invasive peripheral adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, Uchino K, Tsubota N. Discrepancy of computed tomographic image between lung and mediastinal windows as a prognostic implication in small lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1828–32. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01077-4. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki K, Koike T, Asakawa T, Kusumoto M, Asamura H, Nagai K, et al. A prospective radiological study of thin-section computed tomography to predict pathological noninvasiveness in peripheral clinical IA lung cancer (Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201) J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:751–6. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821038ab. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821038ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki K, Koike T, Asamura H, Nagai K. Radiologic-pathologic correlation in stage IA adenocarcinoma of the lung. Proceedings of ASCO; Chicago: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki K, Kusumoto M, Watanabe S, Tsuchiya R, Asamura H. Radiologic classification of small adenocarcinoma of the lung: radiologic-pathologic correlation and its prognostic impact. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.058. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki K, Yokose T, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Takahashi K, Nagai K, et al. Prognostic significance of the size of central fibrosis in peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:893–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01331-4. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(99)01331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takamochi K, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Suzuki K, Ohde Y, Nishimura M, et al. Pathologic N0 status in pulmonary adenocarcinoma is predictable by combining serum carcinoembryonic antigen level and computed tomographic findings. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:325–30. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.114355. doi:10.1067/mtc.2001.114355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang HJ, Lee KS, Kwon OJ, Rhee CH, Shim YM, Han J. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: focal area of ground-glass attenuation at thin-section CT as an early sign. Radiology. 1996;199:485–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.2.8668800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim EA, Johkoh T, Lee KS, Han J, Fujimoto K, Sadohara J, et al. Quantification of ground-glass opacity on high-resolution CT of small peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung: pathologic and prognostic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:1417–22. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:615–22. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okada M, Koike T, Higashiyama M, Yamato Y, Kodama K, Tsubota N. Radical sublobar resection for small-sized non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:769–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.063. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa K, Tsubota N, Kodama K, Ayabe H, Taki T, Mori T. Prospective study of extended segmentectomy for small lung tumors: the final report. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1055–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03466-x. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03466-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sherif A, Gooding WE, Santos R, Pettiford B, Ferson PF, Fernando HC, et al. Outcomes of sublobar resection versus lobectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a 13-year analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:408–15. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.029. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ost DE, Gould MK. Decision making in patients with pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:363–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0679CI. doi:10.1164/rccm.201104-0679CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armato SG, 3rd, McNitt-Gray MF, Reeves AP, Meyer CR, McLennan G, Aberle DR, et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC): an evaluation of radiologist variability in the identification of lung nodules on CT scans. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:1409–21. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.07.008. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S, Suzuki K, MacMahon H. Development and evaluation of a computer-aided diagnostic scheme for lung nodule detection in chest radiographs by means of two-stage nodule enhancement with support vector classification. Med Phys. 2011;38:1844–58. doi: 10.1118/1.3561504. doi:10.1118/1.3561504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe S, Watanabe T, Arai K, Kasai T, Haratake J, Urayama H. Results of wedge resection for focal bronchioloalveolar carcinoma showing pure ground-glass attenuation on computed tomography. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1071–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03623-2. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamato Y, Tsuchida M, Watanabe T, Aoki T, Koizumi N, Umezu H, et al. Early results of a prospective study of limited resection for bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:971–4. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02507-8. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02507-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida J, Ishii G, Yokose T, Aokage K, Hishida T, Nishimura M, et al. Possible delayed cut-end recurrence after limited resection for ground-glass opacity adenocarcinoma, intraoperatively diagnosed as Noguchi type B, in three patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:546–50. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d0a480. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d0a480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida J, Nagai K, Yokose T, Nishimura M, Kakinuma R, Ohmatsu H, et al. Limited resection trial for pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodules: fifty-case experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:991–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.038. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noguchi M, Morikawa A, Kawasaki M, Matsuno Y, Yamada T, Hirohashi S, et al. Small adenocarcinoma of the lung. Histologic characteristics and prognosis. Cancer. 1995;75:2844–52. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2844::aid-cncr2820751209>3.0.co;2-#. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2844::AID-CNCR2820751209>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimosato Y, Suzuki A, Hashimoto T, Nishiwaki Y, Kodama T, Yoneyama T, et al. Prognostic implications of fibrotic focus (scar) in small peripheral lung cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:365–73. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198008000-00005. doi:10.1097/00000478-198008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsubota N, Ayabe K, Doi O, Mori T, Namikawa S, Taki T, et al. Ongoing prospective study of segmentectomy for small lung tumors. Study Group of Extended Segmentectomy for small lung tumor. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1787–90. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00819-4. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(98)00819-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]