Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Preoperative atrial fibrillation (PAF) has been associated with poorer early and mid-term outcomes after isolated valvular or coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Few studies, however, have evaluated the impact of PAF on early and mid-term outcomes after concomitant aortic valve replacement and coronary aortic bypass graft (AVR-CABG) surgery.

METHODS

Data obtained prospectively between June 2001 and December 2009 by the Australian and New Zealand Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Surgery Database Program was retrospectively analysed. Patients who underwent concomitant atrial arrhythmia surgery/ablation were excluded. Demographic and operative data were compared between patients undergoing concomitant AVR-CABG who presented with PAF and those who did not using chi-square and t-tests. The independent impact of PAF on 12 short-term complications and mid-term mortality was determined using binary logistic and Cox regression, respectively.

RESULTS

Concomitant AVR-CABG surgery was performed in 2563 patients; 322 (12.6%) presented with PAF. PAF patients were generally older (mean age 76 vs 74 years; P < 0.001) and presented more often with comorbidities including congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease and cerebrovascular disease (all P < 0.05). PAF was associated with 30-day mortality on univariate analysis (P = 0.019) but not multivariate analysis (P = 0.53). The incidence of early complications was not significantly higher in the PAF group. PAF was independently associated with reduced mid-term survival (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.14–2.19; P = 0.006).

CONCLUSIONS

PAF is associated with reduced mid-term survival after concomitant AVR-CABG surgery. Patients with PAF undergoing AVR-CABG should be considered for a concomitant surgical ablation procedure.

Keywords: Cardiac surgery, Coronary artery bypass graft, CABG, Aortic valve replacement, Preoperative atrial fibrillation, Mortality, Morbidity, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Concomitant aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass graft (AVR-CABG) surgery is an effective treatment for aortocoronary disease, even in high-risk populations [1]. The popularity of this procedure has increased in recent years, in contrast to isolated AVR and CABG surgery [2, 3]. Atrial fibrillation is the most common abnormal cardiac rhythm and frequently accompanies other cardiovascular disease [4, 5]. Long-lasting atrial fibrillation is a cause of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy and has been independently associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of premature death [6]. The incidence of preoperative atrial fibrillation (PAF) in patients undergoing cardiac surgery ranges from 1 to 40% [7, 8]. The incidence of PAF is generally highest in patients undergoing mitral valve surgery and is lowest in those undergoing CABG surgery. Several studies have shown that this affliction is associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality and poorer early outcomes after cardiac surgery [9–11]. Moreover, PAF has been associated with a reduced long-term event-free and overall survival after isolated valvular or CABG surgery [8, 11–15]. Consequently, there is growing enthusiasm for concomitant surgical AF ablation procedures during other cardiac surgical operations [16, 17]. Few studies, however, have evaluated the impact of PAF on early and mid-term outcomes after concomitant AVR-CABG. This is unfortunate given that the incidence of PAF is higher in patients undergoing AVR-CABG surgery compared with isolated AVR or CABG. Moreover, concomitant AVR-CABG is a more technically challenging procedure than isolated AVR or CABG surgery, and patients are generally older with greater comorbidities. It is imperative, therefore, to determine the prognostic impact of PAF in this relatively high-risk patient population. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of PAF on early and mid-term outcomes after concomitant AVR-CABG surgery using a large, multi-institutional Australian database.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The inclusion criterion for the study was patients undergoing concomitant AVR and CABG between 1 June 2001 and 31 December 2009, at hospitals in Australia participating in the Australian and New Zealand Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (Cardiac Surgery Database). Patients having isolated AVR or CABG were excluded from this study. Patients having any other concomitant cardiac surgical procedures, in particular, atrial arrhythmia surgery, were excluded. A detailed description of data collection and validation methods has been previously provided [18, 19].

PAF was defined as evidence of a PAF by clinical documentation, which required treatment. For the purpose of this study, patients were separated into two groups based on the presence of PAF group or not (no PAF group). Preoperative characteristics, early outcomes and mid-term survival were compared between the two groups. Short-term outcomes specifically referred to the outcomes during hospital stay. Mid-term mortality was defined as death from any cause that occurred at any time after hospital discharge. Preoperative AF is treated in several ways and there is variation in management from patient to patient. The majority of patients are rate controlled using medications such as β-blockers (mainly metoprolol) or digoxin. Some patients are under rhythm control using amiodarone. Our database, unfortunately, does not contain specific data on the treatment of preoperative AF.

Twelve early postoperative outcomes were analysed. These were (a) 30-day mortality, defined as death within 30 days of operation; (b) permanent stroke, defined as a new central neurological deficit persisting for >72 h; (c) postoperative acute myocardial infarction, defined as at least two of the following: enzyme-level elevation, new cardiac wall motion abnormalities and new Q waves on serial electrocardiograms; (d) new renal failure, defined as at least two of the following: serum creatinine increased to >200 µmol/l, doubling or greater increase in creatinine vs preoperative value and new requirement for dialysis or haemofiltration; (e) prolonged ventilation (>24 h); (f) multisystem failure; defined as concurrent failure of two or more of the cardiac, respiratory or renal systems for at least 48 h; (g) gastrointestinal (GI) complications; defined as postoperative occurrence of any GI complication; (h) deep sternal infection involving muscle and bone as demonstrated by surgical exploration and one of the following: positive cultures or treatment with antibiotics; (i) pneumonia diagnosed by one of the following: positive cultures of sputum, blood, pleural fluid, empyema fluid, trans-tracheal fluid or trans-thoracic fluid; consistent with the diagnosis and clinical findings of pneumonia; (j) return to the operating theatre for any cause; (k) return to the operating theatre for bleeding; and (l) readmission within 30 days of surgery. Moreover, a composite endpoint titled ‘any morbidity/mortality’ was assessed encompassing all the complications listed above.

To assess the impact of PAF on each outcome, logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for 19 preoperative patient variables, with the outcome as the dependent variable. The mid-term survival status was obtained from the Australian National Death Index. The closing date was 18 March 2010. A Kaplan–Meier estimate of survival was obtained. Differences in mid-term survival were assessed by the log-rank test. The role of PAF in mid-term survival was assessed by constructing a Cox proportional hazards model using PAF and other preoperative patient characteristics as variables. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± 1 standard deviation (SD). The independent samples t-test was used to compare two groups of continuous variables. The Fisher exact test or the chi-squared test was used to compare groups of categoric variables. All calculated values of P were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® for Windows version 17.0 (SPSS, Munich, Germany).

RESULTS

Concomitant AVR-CABG surgery was undertaken in 2563 patients at 20 Australian institutions. Of these, 322 (12.6%) patients presented with PAF. Preoperative and demographic characteristics of patients, stratified by the presence of PAF are summarized in Table 1. There were some differences in intraoperative variables between the two groups. These are summarized in Table 2. The incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in this group of 2563 patients was 39.8%; this is significantly higher than the incidence of PAF. Overall, 1106 (43.2%) patients developed a new cardiac arrhythmia during the postoperative period; the remaining 56.8% of patients remained in sinus rhythm throughout.

Table 1:

Preoperative characteristics of patients with and without preoperative atrial fibrillation

| Preoperative variables | No PAF | PAF | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients (%) | 2241 | 322 | – |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 73.8 ± 8.3 | 75.9 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 710 (31.7) | (32.6) | 0.749 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (%) | 389 (17.4) | 73 (22.7) | 0.024 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 692 (30.9) | 105 (32.6) | 0.563 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (%) | 1617 (72.2) | 198 (61.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 1794 (80.1) | 257 (79.8) | 0.881 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 380 (17.0) | 73 (22.7) | 0.015 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 340 (15.2) | 55 (17.1) | 0.363 |

| Renal failure (%) | 88 (3.9) | 20 (6.2) | 0.073 |

| Previous cardiac surgery (%) | 133 (5.9) | 18 (5.6) | 0.900 |

| Recent myocardial infarction (<21 days) (%) | 223 (10.0) | 40 (12.4) | 0.170 |

| History of congestive heart failure (%) | 749 (33.4) | 171 (53.1) | <0.001 |

| Triple vessel disease (%) | 835 (37.3) | 113 (35.1) | 0.460 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | – | – | 0.001 |

| Normal (EF > 0.60) (%) | 1232 (55.0) | 145 (45.0) | – |

| Mild (EF > 0.45) (%) | 554 (24.7) | 85 (26.4) | – |

| Moderate (EF 0.30–0.45) (%) | 286 (12.8) | 58 (18.0) | – |

| Severe (EF < 0.30) (%) | 116 (5.2) | 28 (8.7) | – |

| Obesity (%) | 710 (31.7) | 104 (32.3) | 0.848 |

| Current smoker (%) | 140 (6.2) | 21 (6.5) | 0.807 |

| New York Heart Association classification | – | – | 0.002 |

| Class I (%) | 404 (18.0) | 41 (12.7) | – |

| Class II (%) | 807 (36.0) | 109 (33.9) | – |

| Class III (%) | 817 (36.5) | 124 (38.5) | – |

| Class IV (%) | 166 (7.4) | 41 (12.7) | – |

| Status | – | – | 0.134 |

| Elective (%) | 1687 (75.3) | 225 (70.0) | – |

| Urgent (%) | 516 (23.0) | 91 (28.3) | |

| Emergency (%) | 32 (1.4) | 6 (1.9) | – |

| Salvage (%) | 6 (0.3) | 0 (0) | – |

| Critical preoperative state (%) | 118 (5.3) | 26 (8.1) | 0.051 |

| EuroSCORE (additive) (mean ± SD) | 9.8 ± 3.1 | 10.9 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

Table 2:

Intraoperative characteristics of patients with and without preoperative atrial fibrillation

| Preoperative variables | No PAF | PAF | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients (%) | – | ||

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (min) (mean ± SD) | 146.65 ± 46.50 | 144.15 ± 44.86 | 0.365 |

| Aortic cross-clamp time (min) (mean ± SD) | 116.34 ± 40.05 | 111.09 ± 33.83 | 0.025 |

| Number of grafts (mean ± SD) | 2.21 ± 1.15 | 2.08 ± 1.11 | 0.049 |

| Internal mammary artery used (%) | 1606 (71.7) | 212 (65.8) | 0.036 |

| Type of prosthesis | – | – | 0.852 |

| Bioprosthesis (%) | 1814 (81.0) | 259 (80.4) | – |

| Mechanical valve (%) | 345 (15.4) | 51 (15.8) | – |

| Homograft (%) | 15 (0.7) | 3 (0.9) | – |

| Valve size (mean ± SD) | 22.96 ± 2.15 | 23.13 ± 2.29 | 0.163 |

Overall 30-day mortality and in-hospital mortality were 3.8 and 4.2%, respectively. The unadjusted 30-day mortality rate in patients with and without PAF was 6.2 and 3.4%, respectively. This was significant on univariate analysis (P = 0.019). The independent association of PAF with other postoperative outcomes is summarized in Table 3. The logistic regression model predicting 30-day mortality is shown in Table 4. This model demonstrates that PAF was not independently associated with 30-day mortality (P = 0.53). This model has a Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 statistic of 8.5 (P = 0.39).

Table 3:

Early outcomes of patients with and without preoperative atrial fibrillation

| Outcomes | No PAF | PAF | P | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent stroke (%) | 53 (2.4) | 5 (1.6) | 0.89 | 1.08 (0.35–3.33) |

| Postoperative myocardial infarction (%) | 24 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | – |

| New renal failure (%) | 185 (8.3) | 42 (13.0) | 0.28 | 1.32 (0.80–2.18) |

| Deep sternal wound infection (%) | 26 (1.2) | 3 (0.9) | 0.28 | 0.32 (0.04–2.54) |

| Pneumonia (%) | 133 (5.9) | 29 (9.0) | 0.94 | 1.02 (0.57–1.83) |

| Multisystem failure (%) | 45 (2.0) | 15 (4.7) | 0.34 | 1.49 (0.66–3.36) |

| Prolonged ventilation (%) | 328 (14.6) | 62 (19.3) | 0.67 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

| Gastrointestinal complications (%) | 43 (1.9) | 15 (4.7) | 0.60 | 1.29 (0.50–3.39) |

| Return to theatre (%) | 191 (8.5) | 36 (11.2) | 0.71 | 1.10 (0.65–1.88) |

| Return to theatre for bleeding (%) | 93 (4.1) | 13 (4.0) | 0.56 | 1.26 (0.58–2.77) |

| 30-day readmission (%) | 280 (12.5) | 40 (12.4) | 0.65 | 1.11 (0.70–1.78) |

| Any mortality/morbidity | 795 (35.5) | 136 (42.2) | 0.35 | 1.17 (0.84–1.63) |

Table 4:

Predictive factors for 30-day and mid-term mortality in all patients

| Preoperative variables | 30-day mortality |

Mid-term mortality |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 1.00 (0.96–1.050 | 0.94 | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | <0.01 |

| Preoperative atrial fibrillation | 1.26 (0.61–2.63) | 0.53 | 1.58 (1.14–2.19) | 0.006* |

| Female | 1.17 (0.62–2.22) | 0.63 | 1.14 (0.84–1.56) | 0.40 |

| Current smoker | 0.88 (0.33–2.37) | 0.80 | 0.96 (0.63–1.46) | 0.84 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.85 (0.45–1.6) | 0.61 | 1.15 (0.87–1.53) | 0.33 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.88 (0.49–1.6) | 0.68 | 1.14 (0.88–1.48) | 0.34 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 0.78 (0.42–1.43) | 0.42 | 0.79 (0.60–1.05) | 0.10 |

| Hypertension | 0.93 (0.47–1.82) | 0.82 | 0.85 (0.64–1.14) | 0.29 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.84 (0.37–1.92) | 0.68 | 1.03 (0.68–1.56) | 0.89 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.97 (0.49–1.9) | 0.93 | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 0.80 |

| Renal failure | 1.22 (0.39–3.79) | 0.73 | 1.29 (0.77–2.18) | 0.34 |

| Critical preoperative state | 0.93 (0.28–3.09) | 0.90 | 1.32 (0.76–2.30) | 0.33 |

| Triple vessel disease | 1.15 (0.67–1.99) | 0.61 | 1.19 (0.93–1.52) | 0.17 |

| Obesity | 0.94 (0.51–1.73) | 0.84 | 0.88 (0.66–1.17) | 0.37 |

| Recent myocardial infarction (<21 days) | 0.41 (0.15–1.14) | 0.09 | 1.01 (0.64–1.59) | 0.96 |

| History of congestive heart failure (%) | 0.86 (0.48–1.54) | 0.61 | 1.18 (0.91–1.54) | 0.22 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <0.45 | 0.98 (0.51–1.92) | 0.96 | 1.35 (0.99–1.83) | 0.06 |

| New York Heart Association Classification III or IV | 1.9 (1.06–3.41) | 0.03 | 0.94 (0.72–1.22) | 0.65 |

| Non-elective procedure | 1.43 (0.77–2.66) | 0.25 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 0.95 |

| EuroSCORE (additive) (mean ± SD) | 1.23 (1.03–1.46) | 0.02 | 1.08 (0.98–1.18) | 0.11 |

The length of ICU stay in patients with and without PAF was 84.20 ± 143.11 vs 64.77 ± 104.30 h, respectively. This was significant on univariate analysis (P = 0.003). The post-procedure length of stay in patients with and without PAF was 13.12 ± 12.22 vs 11.60 ± 10.39 days, respectively. This was significant on univariate analysis (P = 0.017).

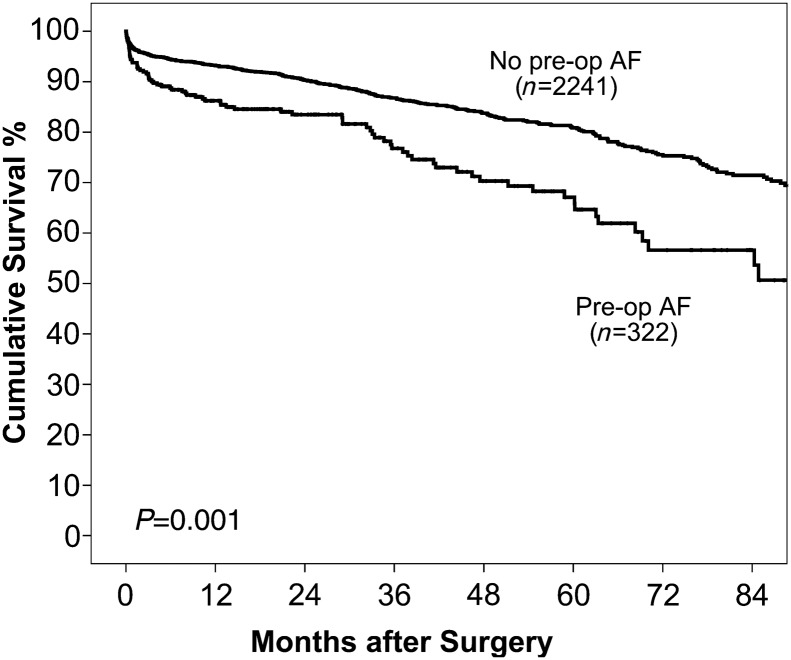

The mean follow-up period for this study was 29 (range 0–105) months. The independent association of PAF with mid-term mortality is summarized in Table 4. PAF was independently associated with reduced mid-term survival (P = 0.006). The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival of patients with and without PAF was 86.2 vs 93.2, 76.8 vs 86.8 and 67.1 vs 80.9%, respectively (Figure 1). We also evaluated the impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on outcomes in this group of 2563 patients. After accounting for confounding factors, postoperative atrial fibrillation was not associated with poorer mid-term outcomes (HR, 1.02; 95% C.I, 0.79 = 1.31; P = 0.890).

Figure 1:

Overall survival of patients with and without preoperative atrial fibrillation.

DISCUSSION

There is a paucity of data, which have specifically evaluated the impact of PAF on the early and mid-term outcomes after concomitant AVR-CABG surgery. In comparison, several studies have evaluated the impact of PAF on outcomes after isolated CABG/AVR surgery or cardiac surgery in general. The aim of this study was to address this critical deficit in the literature.

The incidence of PAF in our study of 2563 patients was 12.6%; this is consistent with the reported literature. The early mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with PAF on univariate analysis (6.2 vs 3.4%; P = 0.019). When multivariate analyses were performed, however, PAF was not associated with 30-day mortality (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.61–2.63; P = 0.53). This may reflect the fact that our study lacks the statistical power to demonstrate a significant association between PAF and 30-day mortality. It is more likely, however, that confounding factors more prevalent in the PAF study population account for the higher 30-day mortality observed in that group. Indeed patients with PAF were 5 years older at the time of cardiac surgery and more frequently presented with comorbidities associated with early mortality including diabetes, congestive heart failure, renal failure and peripheral vascular disease. These factors, in particular advanced age, are known to be associated with an increased risk of early mortality. The higher operative risk of patients with PAF is reflected by a higher additive EuroSCORE (10.9 vs 9.8; P < 0.001). These factors would have contributed to the increased 30-day mortality observed in this group. Our findings are commensurate with those reported by Ngaage et al. [10] who showed that patients with PAF undergoing isolated AVR were significantly older and sicker at the time of surgery. When these comorbidities were taken into account, PAF was not predictive of postoperative morbidity (P = 0.08). Conversely, Levy et al. [9] in a small series of 83 patients with severe aortic stenosis (area < 1 cm2) and impaired ejection fraction (≤35%) undergoing AVR demonstrated that PAF was an independent predictor of perioperative mortality (24 vs 5.5%; P = 0.003). Ad and colleagues [9] used the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Cardiac Surgery Database to analyse the outcomes of 281 567 patients undergoing isolated CABG surgery. The authors also demonstrated that PAF was an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality (5.2 vs 2.2%; P < 0.001). Conflicting data, therefore, have been published regarding the impact of PAF on early mortality in cardiac surgery. There are several reasons why our study may not have shown an independent association of PAF with 30-day mortality. First, our sample size may not have been large enough to detect a real difference. Secondly, confounding factors and the poorer preoperative characteristics of the PAF patient population may have rendered it difficult to determine the true prognostic impact of PAF. Further investigation, more specifically evaluating the impact of PAF on outcomes after concomitant AVR-CABG surgery, is necessary.

Preoperative atrial fibrillation was not associated with an increased incidence of any of the 11 other postoperative outcomes evaluated. Importantly, the composite end-point ‘any mortality/morbidity’ encompassing all early postoperative outcomes did not differ significantly differ between patients who did have PAF and those who did not. In contrast, Ngaage et al. [10] demonstrated an association of PAF with all-cause morbidity after isolated AVR. Stroke is an important complication after cardiac surgery, and some studies have implicated PAF as a significant risk factor. Ad et al. [20] demonstrated that PAF independently increased the risk of stroke in patients undergoing isolated CABG surgery (2.6 vs 1.5%; P < 0.001). In contrast, our study did not show any association of PAF with stroke (1.6 vs 2.4%; P = 0.89). Similar findings have been reported elsewhere [8, 11, 14]. There was a trend towards increased incidence of postoperative renal dysfunction/failure in the current study, but this did not reach statistical significance (13.0 vs 8.3%; P = 0.28). In contrast to the findings of Ad et al. [20], the incidence of prolonged ventilation or reoperation was not significantly higher in the PAF group; this may, however, reflect a significantly smaller sample size. Similar to the findings of other studies, PAF was also associated with an increased post-procedural length of hospital stay and ICU stay [11, 14]. Given that these factors are associated with resource utilization, PAF is likely to increase the overall cost of hospitalization after AVR-CABG surgery. Unfortunately, cost data were not available in the current study. Evaluating the cost differences in outcomes between patients with and without PAF is an important topic, which warrants further investigation.

An assessment of mid-term outcomes demonstrated that PAF increased the incidence of all-cause mortality in patients who underwent AVR-CABG by over 50% (odds ratio, 1.58; P = 0.006). The 5-year survival in patients with and without PAF was 86.8 and 67.1%, respectively. It must be noted, however, that patients with PAF were significantly older. Advanced age has been consistently shown to be an important risk factor for late mortality after isolated or combined cardiac surgery [21, 22]. It is possible that, despite accounting for age in the multivariable model, advanced age may have been partially responsible for the higher mid-term mortality that was observed in patients with PAF. PAF has been previously shown to reduce mid-term survival after cardiac surgery, though not specifically for AVR-CABG. A study from the Mayo Clinic compared the mid-term outcomes of 257 patients with PAF and matched controls in sinus rhythm undergoing isolated CABG surgery [14]. The authors demonstrated that PAF increased all-cause mortality in patients by 40%. PAF also nearly tripled the likelihood of cardiac death (odds ratio 2.8) and the risk of major cardiac events by 2.5 times. Rogers et al. [11] evaluated the outcomes of 5092 patients who underwent CABG, including 175 with PAF, at the Bristol Heart Institute. They showed that even after adjustment for differences between the groups, the overall risk for mid-term mortality was 49% higher in patients with PAF. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere [8]. The association of PAF with mid-term outcomes after valvular surgery requires further evaluation. Jessurun et al. [7] demonstrated that 4-year survival did not differ between patients with preoperative sinus rhythm (95.2%), paroxysmal AF (89.2%) and chronic AF (82.9%) (P = 0.13). Ngaage et al. [10] showed that 7-year overall survival was lower in patients with PAF on univariate analysis (50 vs 61%; P = 0.03) but not on multivariate analysis (P = 0.38). There was no difference in death from cardiac causes between the groups (P = 0.30). Levy et al. [9] showed that PAF was an independent risk factor for late mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction undergoing AVR (5-year survival; 47 vs 77%; P = 0.0017). Overall, the consensus in the scientific community is that PAF is an independent risk factor for a poor outcome and our data support this view.

Given the poorer late outcomes, several investigators have advocated surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation as an adjunctive procedure in the management of patients with a history of PAF [23]. The results of both the combined and isolated procedures have been good, with relatively low rates of perioperative complications and significantly reduced risk for long-term thromboembolic events and strokes [23, 24]. Long-term survival benefits have also been reported [25]. Recent advancements in ablative techniques have expanded the repertoire available to surgeons regarding the treatment of PAF [17]. Nevertheless, surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation is far from being applied in all cases in which there is an indication for the procedure. Furthermore, although PAF is associated with reduced mid-term survival, there is currently insufficient evidence that an atrial ablation strategy produces survival benefits in the context of AVR-CABG surgery. This is a shortcoming in the current literature, which should be addressed by a prospective or randomized study.

Limitations

The current study has several advantages and disadvantages. A major advantage is that it is a large, contemporary, multi-institutional study, which is likely to reflect contemporary practice reasonably accurately. Our study is also one of the few studies which has evaluated the prognostic impact of PAF after concomitant AVR-CABG surgery. The major disadvantage is that it is a retrospective review. As such, selection bias and confounding from unknown variables is likely to be present. Our study clearly demonstrated that patients who had PAF were older and had more comorbidities including congestive heart failure, impaired ventricular function and cerebrovascular disease; this was reflected in a significantly higher EuroSCORE (10.9 vs 9.8; P < 0.001).

Moreover, the retrospective nature of the study did not allow us to precisely classify patients according to the current accepted definitions of paroxysmal, persistent and permanent AF. The association observed between PAF and mid-term mortality also does not necessarily imply causation. Although, cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarction secondary to AF is well established, our study does not provide autopsy results and only all-cause mortality was considered. Our dataset lacks information on drug medication preoperatively, at discharge and during follow-up. In particular, knowledge about the administration of antiarrhythmic medication and long-term use of anticoagulation therapy during the postoperative period would have been useful. Also, our database did not allow us to categorize patients based on the type of AF (e.g. permanent, paroxysmal etc.). As a result, we were unable to ascertain the prognostic implication of the various types of PAF on early and mid-term outcomes. In addition, preoperative characteristics between patients are likely to differ based on the arrhythmia subtype. This limitation is not unique to our database; other studies have been unable to evaluate the impact of PAF type on early and mid-term outcomes [8, 11, 15]. A prospective investigation with clear classification of patients according to PAF subtype is necessary to address this important clinical question. Nevertheless, despite its limitation, our study reaffirms, with sufficient conviction, that PAF affects mid-term outcomes after AVR-CABG surgery.

In conclusion, PAF is associated with an increased risk of mid-term mortality, but not early mortality, after concomitant AVR-CABG. As such, concomitant atrial ablation with AVR-CABG may be an appropriate strategy. Given the paucity of data evaluating the impact of PAF in the context of AVR-CABG, further prospective investigation is still necessary. In particular, further studies would benefit from a longer period of follow-up.

Funding

The Australian and New Zealand Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (ANZSCTS) National Cardiac Surgery Database Program is funded by the Department of Human Services, Victoria, and the Health Administration Corporation and the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC), NSW.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ANZSCTS data management centre, CCRE, Monash University: Chris Reid, Lavinia Tran, Diem Dinh, Angela Brennan.

ANZSCTS DATABASE PROGRAM STEERING COMMITTEE

Mr Gil Shardey (Chair), Mr Peter Skillington, Prof Julian Smith, Mr Andrew Newcomb, Mr Siven Seevanayagam, Mr Bo Zhang, Mr Hugh Wolfenden, Mr Adrian Pick, Prof Chris Reid, Dr Lavinia Tran, Dr Diem Dinh, Mr Andrew Clarke.

The Australian and New Zealand Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (ANZSCTS) National Cardiac Surgery Database Program is funded by the Department of Human Services, Victoria, and the Health Administration Corporation and the Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC), NSW.

The following investigators, data managers and institutions participated in the ANZSCTS Database: Alfred Hospital: Pick A, Duncan J; Austin Hospital: Seevanayagam S, Shaw M; Cabrini Health: Shardey G; Geelong Hospital: Morteza M, Zhang B, Bright C; Flinders Medical Centre: Knight J, Baker R, Helm J, Canning N; Jessie McPherson Private Hospital: Smith J, Baxter H; Hospital: John Hunter Hospital: James A, Scaybrook S; Lake Macquarie Hospital: Dennett B, Mills M; Liverpool Hospital: French B, Hewitt N; Mater Health Services: Diqer AM, Curtis L; Monash Medical Centre: Smith J, Baxter H; Prince of Wales Hospital: Wolfenden H, Weerasinge D; Royal Melbourne Hospital: Skillington P, Law S; Royal Prince Alfred Hospital: Wilson M, Turner L; St George Hospital: Fermanis G, Newbon P; St Vincent's Hospital, VIC: Yii M, Newcomb A, Mack J, Duve K; St Vincent's Hospital, NSW: Spratt P, Hunter T; The Canberra Hospital: Bissaker P, Bhosale M; Townsville Hospital: Tam R, Farley A; Westmead Hospital: Costa R, Halaka M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dagenais F, Mathieu P, Doyle D, Dumont E, Voisine P. Moderate aortic stenosis in coronary artery bypass grafting patients more than 70 years of age: to replace or not to replace? Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.036. discussion 1499–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahian DM, Edwards FH. The society of thoracic surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: introduction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:S1. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, de Leon AC, Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannel WB, Abbott RD, Savage DD, McNamara PM. Epidemiologic features of chronic atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1018–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204293061703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart RG, Sherman DG, Easton JD, Cairns JA. Prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Neurology. 1998;51:674–81. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jessurun ER, van Hemel NM, Kelder JC, Elbers S, de la Riviere AB, Defauw JJ, et al. Mitral valve surgery and atrial fibrillation: is atrial fibrillation surgery also needed? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:530–7. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quader MA, McCarthy PM, Gillinov AM, Alster JM, Cosgrove DM, III, Lytle BW, et al. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation reduce survival after coronary artery bypass grafting? Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.069. Discussion 1522–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy F, Garayalde E, Quere JP, Ianetta-Peltier M, Peltier M, Tribouilloy C. Prognostic value of preoperative atrial fibrillation in patients with aortic stenosis and low ejection fraction having aortic valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:809–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngaage DL, Schaff HV, Barnes SA, Sundt TM, III, Mullany CJ, Dearani JA, et al. Prognostic implications of preoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement: is there an argument for concomitant arrhythmia surgery? Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1392–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers CA, Angelini GD, Culliford LA, Capoun R, Ascione R. Coronary surgery in patients with preexisting chronic atrial fibrillation: early and midterm clinical outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schonburg M, Ziegelhoeffer T, Weinbrenner F, Bechtel M, Detter C, Krabatsch T, et al. Preexisting atrial fibrillation as predictor for late-time mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing cardiac surgery—a multicenter study. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:128–32. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-989432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulenberg R, Antonitsis P, Stroebel A, Westaby S. Chronic atrial fibrillation is associated with reduced survival after aortic and double valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:738–44. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngaage DL, Schaff HV, Mullany CJ, Sundt TM, III, Dearani JA, Barnes S, et al. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation influence early and late outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:182–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalavrouziotis D, Buth KJ, Vyas T, Ali IS. Preoperative atrial fibrillation decreases event-free survival following cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36:293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiappini B, Martin-Suarez S, LoForte A, Arpesella G, Di Bartolomeo R, Marinelli G. Cox/maze iii operation versus radiofrequency ablation for the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation: a comparative study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox JL, Ad N. New surgical and catheter-based modifications of the maze procedure. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(00)70020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinh DT, Lee GA, Billah B, Smith JA, Shardey GC, Reid CM. Trends in coronary artery bypass graft surgery in Victoria, 2001–2006: findings from the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons database project. Med J Aust. 2008;188:214–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxena A, Poh CL, Dinh DT, Smith JA, Shardey GC, Newcomb AE. Early and late outcomes after isolated aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: an Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons Cardiac Surgery Database Study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ad N, Barnett SD, Haan CK, O'Brien SM, Milford-Beland S, Speir AM. Does preoperative atrial fibrillation increase the risk for mortality and morbidity after coronary artery bypass grafting? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:901–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxena A, Dinh D, Poh CL, Smith JA, Shardey G, Newcomb AE. Analysis of early and late outcomes after concomitant aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass graft surgery in octogenarians: a multi-institutional Australian study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1759–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxena A, Dinh DT, Yap CH, Reid CM, Billah B, Smith JA, et al. Critical analysis of early and late outcomes after isolated coronary artery bypass surgery in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1703–11. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deneke T, Khargi K, Lemke B, Lawo T, Lindstaedt M, Germing A, et al. Intra-operative cooled-tip radiofrequency linear atrial ablation to treat permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2909–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sie HT, Beukema WP, Elvan A, Ramdat Misier AR. Long-term results of irrigated radiofrequency modified maze procedure in 200 patients with concomitant cardiac surgery: six years experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:512–6. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01466-8. Discussion 516–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi J, Sasako Y, Bando K, Niwaya K, Tagusari O, Nakajima H, et al. Eight-year experience of combined valve repair for mitral regurgitation and maze procedure. J Heart Valve Dis. 2002;11:165–71. Discussion 171–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]