Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO) due to mitotic diseases is a serious condition with significant morbidity and mortality. The aim of this study was to examine the follow-up data and demographics of patients with SVCO admitted to the Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, over a 14-year period.

METHODS

The prospectively entered clinical data of patients with SVCO in Queen Mary Hospital from October 1997 to September 2011 were retrospectively analysed. All patient records were electronically and manually searched. Survival was calculated using Kaplan–Meier survival curves analysis. The Mantel–Cox log-rank test was used to test for statistically significant differences. Demographic data, associated aetiology, intervention and outcome were studied. Only patients with malignant aetiologies were included.

RESULTS

A total of 104 patients (81 males and 23 females) were recruited in our study period. Median age at presentation was 65 (range 3–91 years). The median follow-up period was 2 months. The commonest cause of SVCO was bronchogenic carcinoma (71%), followed by extrathoracic malignancies (16%), lymphoma (8%) and thymic malignancy (3%). The mean time from the onset of symptoms to presentation was 34 days. Steroids were prescribed for most (93.9%) of the patients. About half (54.4%) of the patients were given radiotherapy. Only 7 patients had angioplasty and all of them had stents inserted. The overall survival was poor. The mean and median survivals were 8.4 and 1.6 months, respectively. Seventeen percent of patients died in the same hospitalization as for their initial presentations. Younger age (50 years or below; P = 0.000), never smoker (P = 0.012), not using steroids (P = 0.007) and certain primary aetiologies (e.g. lymphoma; P = 0.008) were associated with longer overall survival on univariate analysis. However, on multivariate analysis, none of these factors reached statistical significance. The mean survival for cases with lymphoma, extrathoracic malignancies, bronchogenic tumours and thymic tumours was 80.1, 3.4, 3.1 and 1.8 months, respectively. Angioplasty did not show a statistically significant association with the overall survival.

CONCLUSIONS

This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to study the prognostic factors that may affect survival outcome in malignant SVCO. We showed that in patients with malignant aetiology for SVCO, advanced age (more than 50), history of smoking and use of steroids were statistically significantly associated with a poor outcome. The underlying primary malignant aetiology also has an important prognostic significance. Despite advances in medicine, the prognosis of patients with SVCO is still grave.

Keywords: Superior vena cava obstruction, Symptomatology, Long-term outcome

INTRODUCTION

First reported by Hunter [1] on a patient with a large syphilitic ascending aortic aneurysm compressing on the superior vena cava and innominate vein, superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO) syndrome is the constellation of signs and symptoms of impaired venous drainage of the head and neck and upper extremities as a result of external compression, direct invasion or central venous thrombosis at the level of the superior vena cava itself, the great veins that empty into it or the superior cavoatrial junction.

Clinically, patients with SVCO may have acute or chronic presentation, depending on the underlying aetiology [2, 3]. In recent years, catheter-related SVCO seems to have an increasing incidence [2, 4, 5]. However, the majority of the cases with SVCO are still caused by malignancies and are also associated with poor prognosis. A high index of suspicion and prompt diagnosis are essential to alter its outcome.

There are many studies on patients with SVCO, but most are on the Caucasian population [2, 6, 7]. This study aimed to review our experience in managing SVCO in a tertiary-referral centre that serves mainly the oriental population over a 14-year period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The prospectively entered clinical data of patients with SVCO in Queen Mary Hospital from October 1997 to September 2011 were retrospectively analysed.

Relevant data on patient demographics, clinical presentation, associated aetiology, progress and management in terms of conservative, medical, endovascular or surgical modalities were all retrieved from a centralized computer database. For those patients who underwent endovascular intervention, perioperative mortality and the period after operation were recorded.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Survival was calculated using Kaplan–Meier survival curves analysis. The Mantel–Cox log-rank test was used to test for statistically significant differences. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant. All significant factors were entered into multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model. Non-parametric qualitative and quantitative comparisons were performed using the Fisher exact test and the Mann–Whitney U-test, respectively.

RESULTS

A total of 104 patients are recruited in our study period. There were 81 males and 23 females. Median age at presentation was 65 years, ranging from 3 to 91. The median follow-up period was 2 months.

Aetiologies of SVCO are summarized in Table 1: 76 (74%) had bronchogenic carcinoma, 16 (16%) had pulmonary metastasis from extrathoracic primary, 8 (8%) had lymphoma and 3 (3%) had thymic malignancy.

Table 1:

Aetiology of superior vena cava obstruction syndromes (N = 104)a

| Number of patients | |

|---|---|

| Bronchogenic | 76 |

| Extrathoracicb | 16 |

| Lymphomac | 8 |

| Thymic malignancy | 3 |

| Unknown | 1 |

aCause unknown in 1 patient.

bOesophagus 4, head and neck 3, hepatic cell carcinoma 2, small bowel 1, pancreas 1, breast 1, corpus 1, cervix 1, testis 1 and unknown 1.

cSeven diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and 1 T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma.

The mean time from the onset of symptoms to presentation was 34 days. Only 28% of patients were never smokers. All patients either developed symptoms during hospitalization (for the treatment of malignancy) or attended the Emergency Department for their symptoms. The commonest presenting symptom was facial puffiness and neck swelling, followed by shortness of breath, dilated veins and cough (Table 2). Other symptoms included upper limb swelling, hoarseness, plethora, haemoptysis, chest pain, dysphagia and throat pain.

Table 2:

Presenting symptoms

| Symptoms | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Facial puffiness and neck swelling | 76.0 |

| Shortness of breath | 68.3 |

| Dilated veins over head and neck area and/or upper limbs | 63.5 |

| Cough | 51.9 |

| Upper limb swelling | 44.2 |

| Hoarseness | 19.2 |

| Haemoptysis | 19.2 |

| Facial plethora | 15.4 |

| Chest pain | 12.5 |

| Dysphagia | 8.7 |

| Airway obstruction | 1.9 |

| Sore throat | 1.9 |

Chest X-ray was done in all patients. The most frequent findings were widened mediastinum and hilar shadows. Computed tomography (CT) was performed in 91 patients. Bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy were done in 37 and 3 patients, respectively. Steroids were prescribed for most (93.9%) of the patients. About half (54.4%) of the patients were given radiotherapy. Chemotherapy was given to 8 patients with lymphoma. Tracheal stent was inserted in 4 patients. None of our patients received open surgical repair.

Seven patients had angioplasty and all of them had stents inserted. During the procedures, guidewires were advanced through the site of pathology identified by venograms. Balloon dilatation was then performed using Wanda balloon (Boston Scientific Ireland, Galway, Ireland) followed by Wallstent (Boston Scientific Ireland, Galway, Ireland) insertion. Further balloon dilatation was performed if necessary, and a completion venogram was performed to ensure satisfactory angiographic results. Two of them developed restenosis requiring repeated angioplasty, giving a primary patency rate of 83%. None of the patients had a stent insertion in the initial procedure. One patient had a successful reintervention with stent insertion and a 5-month survival. The other patient unfortunately died 48 h after the reintervention.

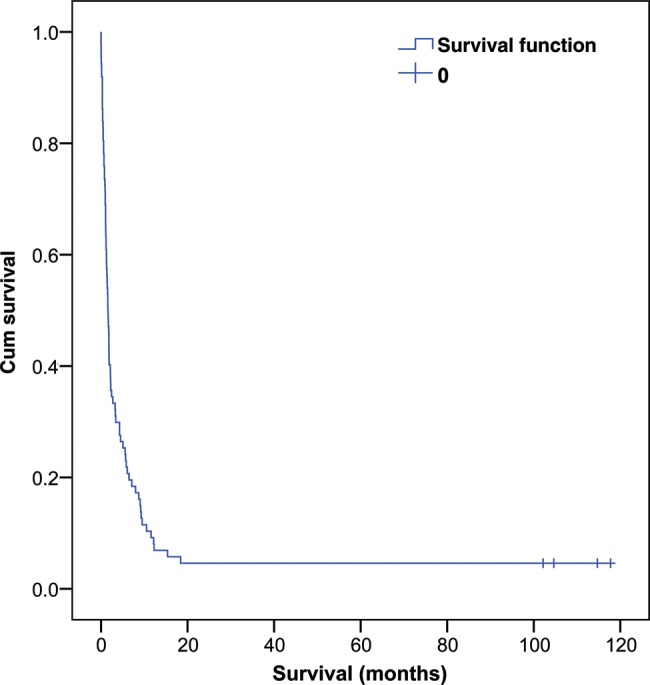

The overall survival was poor. The mean and median survivals were 8.4 and 1.6 months, respectively (Fig. 1). 17% of patients died in the same hospitalization as for their initial presentations. Factors potentially affecting survival were analysed (Table 3). Younger age (50 years or below; P = 0.000), never smoker (P = 0.012), not using steroids (P = 0.007) and certain primary aetiologies (e.g. lymphoma; P = 0.008) were associated with longer overall survival on univariate analysis. However, on multivariate analysis, none of these factors reached statistical significance. The mean survival for cases with lymphoma, extrathoracic malignancies, bronchogenic tumours and thymic tumours was 80.1, 3.4, 3.1 and 1.8 months, respectively. Angioplasty, with or without stenting, did not show a statistically significant association with the overall survival.

Figure 1:

Kaplan–Meier curve for the survival of superior vena cava obstruction patients.

Table 3:

Factors with significant association with overall survival

| P-valuea | Survival (months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.000 | 50 or below | 35.1 |

| >50 | 2.8 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.012 | Never smoker | 35.7 |

| History of smoking | 3.4 | ||

| Steroid use | 0.007 | No steroid | 51.9 |

| Steroid use | 5.9 | ||

| Primary malignancy | 0.008 | Bronchogenic | 3.1 |

| Extrathoracic malignancy | 3.4 | ||

| Lymphoma | 80.1 | ||

| Thymic malignancy | 1.8 |

aIn univariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

The aetiology of SVCO has changed dramatically since William Hunter first described it in 1757 [1]. Infective causes, once the major culprit of SVCO [8, 9], have been largely replaced by malignant causes [10–12]. Intravascular device-related aetiologies have also been an increasingly common cause of SVCO and are responsible for up to 40% of the cases in some series [2, 4, 5]. The pathophysiological basis has been well described in Cheng's review [3].

In most of the literature, patients with SVCO tended to be 50 years or older at presentation. Rice et al. [2] reported that the average age at the time of diagnosis was 57.7 ± 14.4 years. SVCO can also occur in the younger population, often as a result of lymphoma or benign causes. In our study, the median age at presentation was 65 years, ranging from 3 to 91. Rather interestingly, while our series showed a strong male preponderance, female preponderance was observed in some other major series [2].

Regarding symptoms, facial puffiness and neck swelling were the commonest presenting symptoms, both in our series (76%) and in the literature (82%) [2]. Other common symptoms reported included upper extremity swelling, dyspnoea, cough and dilated neck/chest veins [2]. These were also in concordance with our findings. Most patients present after the development of symptoms over days to weeks [6]. Our patients waited for an average of about 1 month (34 days) after the onset of symptoms before presenting to us.

Diagnosis of SVCO is largely based on clinical findings. Subsequent workup is only performed after initial stabilization of patients' vitals. The mainstay of initial treatment is supportive measures, including supplementary oxygen, head elevation, use of diuretics and often a course of parenteral steroids (dexamethasone, 4 mg every 6 h) [3]. Steroids were prescribed for most (93.9%) of our patients. However, to our surprise, it was associated with a worse prognosis on univariate analysis, but was non-significant on multivariate analysis. This could possibly be due to a selection bias. Given the liberal use of steroids on suspicion of SVCO, it is likely that patients who were not prescribed steroids were those with milder symptoms and thus had a better survival.

Anticoagulation is sometimes administered for intravascular thrombus, which frequently coexists with extrinsic mass compression as a result of sluggish flow. In situations where a prompt adequate response is achieved, anticoagulation is usually continued for at least 6 months. Unfortunately, due to the retrospective nature of our study, the drug history was incomplete for diuretics and anticoagulants, rendering them not available for analysis.

The next step after initial stabilization is usually non-invasive imaging to elucidate the aetiology of SVCO and to determine its severity. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful and frequently performed. Regardless of its aetiology, diagnosis of SVCO can be made on the findings of the lack of opacification of the SVC, intraluminal filling defects or severe narrowing of SVC and visualization of collateral vascular channels [13]. CT also provides precious information about the level and extent of obstruction, length of the affected segment and the presence or absence of the distal clot, therefore enabling the interventional radiologist to formulate the optimal treatment plan if intervention is needed [13].

Recent studies on endovascular intervention showed promising results in treating the malignant SVCO syndrome with endovascular stenting. Primary and secondary patencies rate ranged from 84.3 to 88% and 92.5 to 95%, respectively, with a median survival period of 1.5–6.5 months [14, 15]. Most patients were given antiplatelet and anticoagulation medications for variable durations after stenting. Unfortunately, the number of patients receiving endovascular intervention in our series was too small for a meaningful analysis. Open vascular surgery, once the only definitive therapy for patients who were unresponsive to conservative treatment, is now only reserved for cases who failed endovascular intervention.

The median life expectancy of SVCO is approximately 6 months, but the reported estimates vary widely [6, 16, 17]. Survival among patients presenting with SVCO associated with malignant conditions did not seem to differ significantly from those patients with the same type and stage of disease without SVCO [7]. The overall survival in our series was poor, with a median survival of 1.6 months only. Patients with lymphoma have a significantly longer survival (80.1 months) than those with other malignant aetiology.

CONCLUSION

This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to investigate the prognostic factors that may affect survival outcomes in malignant SVCO. We showed that in patients with malignant aetiology for SVCO, advanced age (more than 50), history of smoking and use of steroids were statistically significantly associated with a poor outcome. The underlying primary malignant aetiology also has an important prognostic significance. Despite advances in medicine, the prognosis of patients with SVCO is still grave.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunter W. History of aneurysm of the aorta with some remarks on aneurysm in general. Med Obser Inq. 1757;1:323–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37–42. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng S. Superior vena cava syndrome: a contemporary review of a historic disease. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:16–23. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318188033c. doi:10.1097/CRD.0b013e318188033c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schifferdecker B, Shaw JA, Piemonte TC, Eisenhauer AC. Nonmalignant superior vena cava syndrome: pathophysiology and management. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65:416–23. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20381. doi:10.1002/ccd.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizvi AZ, Kalra M, Bjarnason H, Bower TC, Schleck C, Gloviczki P. Benign superior vena cava syndrome: stenting is now the first line of treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:372–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.071. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schraufnagel DE, Hill R, Leech JA, Pare JA. Superior vena caval obstruction. Is it a medical emergency? Am J Med. 1981;70:1169–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90823-8. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(81)90823-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J. Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1862–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp067190. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp067190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIntire FT, Sykes EM., Jr Obstruction of the superior vena cava: a review of the literature and report of two personal cases. Ann Intern Med. 1949;30:925–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-30-5-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schechter MM. The superior vena cava syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1954;227:46–56. doi: 10.1097/00000441-195401000-00007. doi:10.1097/00000441-195401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen JC, Bongard F, Klein SR. A contemporary perspective on superior vena cava syndrome. Am J Surg. 1990;160:207–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80308-3. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parish JM, Marschke RF, Jr, Dines DE, Lee RE. Etiologic considerations in superior vena cava syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56:407–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kee ST, Kinoshita L, Razavi MK, Nyman UR, Semba CP, Dake MD. Superior vena cava syndrome: treatment with catheter-directed thrombolysis and endovascular stent placement. Radiology. 1998;206:187–93. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qanadli SD, El Hajjam M, Bruckert F, Judet O, Barré O, Chagnon S, et al. Helical CT phlebography of the superior vena cava: diagnosis and evaluation of venous obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1327–33. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.5.10227511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowell NP, Gleeson FV. Steroids, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and stents for superior vena caval obstruction in carcinoma of the bronchus: a systematic review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2002;14:338–51. doi: 10.1053/clon.2002.0095. doi:10.1053/clon.2002.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagata T, Makutani S, Uchida H, Kichikawa K, Maeda M, Yoshioka T, et al. Follow-up results of 71 patients undergoing metallic stent placement for the treatment of a malignant obstruction of the superior vena cava. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:959–67. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9088-4. doi:10.1007/s00270-007-9088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yellin A, Rosen A, Reichert N, Lieberman Y. Superior vena cava syndrome. The myth–the facts. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(5 Pt 1):1114–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.5_Pt_1.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcy PY, Magne N, Bentolila F, Drouillard J, Bruneton JN, Descamps B. Superior vena cava obstruction: is stenting necessary? Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:103–7. doi: 10.1007/s005200000173. doi:10.1007/s005200000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]