Abstract

We conducted phylogenetic analyses and an estimation of coalescence times for East Asian strains of HTLV-1. Phylogenetic analyses showed that the following three lineages exist in Japan: “JPN”, primarily comprising Japanese isolates; “EAS”, comprising Japanese and two Chinese isolates, of which one originated from Chengdu and the other from Fujian; and “GLB1”, comprising isolates from various locations worldwide, including a few Japanese isolates. It was estimated that the JPN and EAS lineages originated as independent lineages approximately 3,900 and 6,000 years ago, respectively. Based on archaeological findings, the “Out of Sunda” hypothesis was recently proposed to clarify the source of the Jomon (early neolithic) cultures of Japan. According to this hypothesis, it is suggested that the arrival of neolithic people in Japan began approximately 10,000 years ago, with a second wave of immigrants arriving between 6,000 and 4,000 years ago, peaking at around 4,000 years ago. Estimated coalescence times of the EAS and JPN lineages place the origins of these lineages within this 6,000–4,000 year period, suggesting that HTLV-1 was introduced to Japan by neolithic immigrants, not Paleo-Mongoloids. Moreover, our data suggest that the other minor lineage, GLB1, may have been introduced to Japan by Africans accompanying European traders several centuries ago, during or after “The Age of Discovery.” Thus, the results of this study greatly increase our understanding of the origins and current distribution of HTLV-1 lineages in Japan and provide further insights into the ethno-epidemiology of HTLV-1.

Keywords: HTLV-1, Phylogeography, Molecular clock, estimation of coalescence time

Introduction

Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) was first isolated from a patient with a T-cell malignancy in 1979 [1]. Many studies have since been conducted, and our understanding of the epidemiology of HTLV-1 has made good progress. HTLV-1 (which does not cause AIDS) originated in primates, including P.t. troglodytes. Phylogenetic studies indicated that some lineages of HTLV-1 found in the Americas were imported along with the human cargo [2]. Although the majority of infected people remain asymptomatic, the virus is associated with severe diseases such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) [3–5]. Three transmission routes exist: mother to child, mostly through breast milk; sexual contact, primarily from male to female; and whole blood transfusion [6–8]. Vertical transmission from mother to child is largely responsible for the distribution pattern of the virus.

Globally, HTLV-1 is found in the Caribbean basin, tropical Africa, Central and South America, and some regions of Melanesia and Japan. Within Japan, the virus is endemic to the southwestern regions, Kyushu and Okinawa, and among indigenous populations living on the island of Hokkaido in the northern part of the country [9–13]. Phylogenetic analyses of the long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences of the virus have indicated three main lineages of HTLV-1 worldwide: the Melanesian subtype, isolated from Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Australian aboriginals; the Central African subtype, from tropical Africa; and the cosmopolitan subtype, from the remaining endemic areas globally [14, 15]. The cosmopolitan subtype is further divided into three subgroups: A, B, and C, which correspond to the transcontinental subgroup, the Japanese subgroup, and the West African subgroup, respectively. The transcontinental subgroup is widely distributed throughout tropical Africa, South America, the Caribbean basin, and Japan [16, 17].

Two different subgroups of HTLV-1, the transcontinental and Japanese subgroups, are found in Japan. The northern part of mainland Kyushu, represented by Hirado and Kumamoto, appears to be monopolized by the Japanese subgroup, whereas the ratio of the transcontinental subgroup ranges from 20% to 35% along the Pacific coast of Shikoku (Kochi Prefecture) and the Ryukyu Archipelago [18].

Based on their analysis of spatial distributions of major HTLV-1 lineages in the Pacific Rim, Miura et al. [19] proposed that Paleo-Mongoloids brought the two HTLV-1 lineages into Japan in the paleolithic period. However, an estimate of arrival times is required before such a hypothesis can be accepted. Thus, in order to better understand the source and distribution of HTLV-1 lineages in Japan as well as to gain valuable insights into the ethno-epidemiology, we conducted phylogenetic analyses on, and estimated the coalescence times of East Asian strains of HTLV-1.

Results

Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Analysis

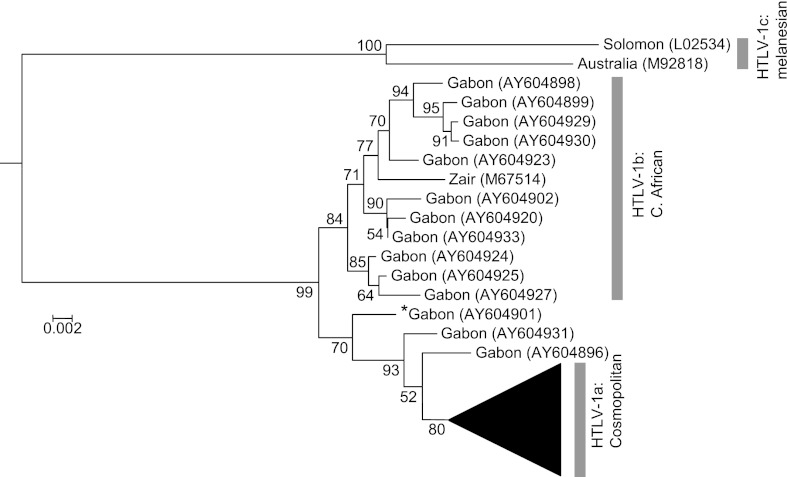

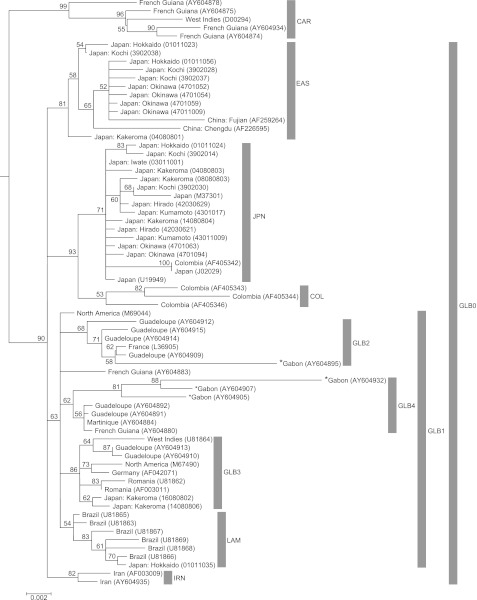

Figures 1 and 2 depict the consensus ML tree re-rooted by designating a STLV-1 isolate of Macaca tonkeana (Z46900) as the outgroup [20, 21].

Fig. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree (ML tree) of HTLV-1, re-rooted by designating a STLV-1 isolate of Macaca tonkeana (Z46900) as the outgroup. HTLV-1a (cosmopolitan subtype) was compressed. The position of the isolate marked with an asterisk was remarkably different between the ML and Bayesian trees (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree (ML tree) of HTLV-1a. The position of the isolate marked with an asterisk was remarkably different between the ML and Bayesian trees (Fig. 3).

The monophyly of HTLV-1a, the cosmopolitan subtype, was moderately supported in the present study (bootstrap value = 80). The bootstrap value gives the strength of support for nodes on phylogenetic trees. Within the HTLV-1a cluster, a monophyletic group comprising isolates from the Caribbean region (CRB) diverged basally (bootstrap value = 99). The sequences of CRB were previously characterized within the Caribbean/W. African subgroup: T5776, T5796, T5838, and C5950 [Yang et al., 1997]. A monophyletic group (GLB0) comprising isolates from Africa, Europe, Iran, East Asia, and South America was also identified as the sister group of CRB (bootstrap value = 90). Within GLB0, four clusters (JPN + COL, IRN, EAS, and GLB1) were identified. Isolates of IRN, EAS, and GLB1, which shared A5904 and A6270, can be identified as the transcontinental subgroup [22]. JPN + COL composed isolates from Japan and Colombia (bootstrap value = 93), and was subdivided into two clusters, JPN and COL. The JPN included Japanese isolates and one Colombian isolate (AF405342) and was weakly supported (bootstrap value = 71). In contrast, the COL, which consisted exclusively of two Colombian isolates, was not well supported. All isolates of JPN shared C5904 and can thus be assigned to the Japanese subgroup previously characterized by Yang et al. [22]. The IRN included two Iranian isolates and was well supported (bootstrap value = 82). EAS included nine isolates from Japan, and two from China, one of which originated from Chengdu and the other from Fujian (bootstrap value = 81). GLB1 included isolates from various locations globally, but this clade was not well supported (bootstrap value = 63). Moreover, GLB1 included four lineages, GLB2, GLB3, GLB4, and LAM, three of which (GLB2, GLB4, and LAM) were not well supported. GLB2 consisted of isolates from W. Africa and the Caribbean region (bootstrap value = 68); GLB3 consisted of isolates from Europe, N. America, the Caribbean region, and Kakeroma, Japan (14080806, 16080802) (bootstrap value = 86); GLB4 consisted of isolates from W. Africa and the Caribbean region (bootstrap value = 62); and LAM consisted of isolates from Brazil and one isolate from Hokkaido, Japan (01011035) (bootstrap value = 54).

Bayesian Analysis for Dating Coalescence of Major Lineages

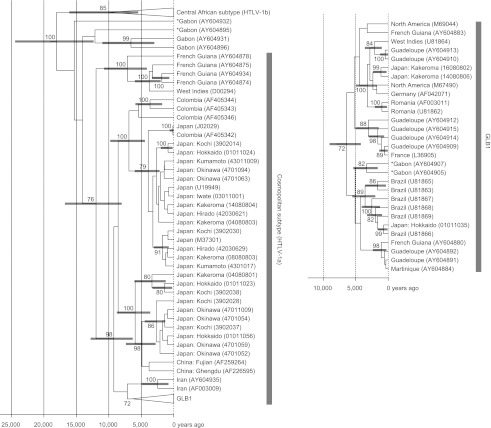

The topology of the Bayesian tree obtained from BEAST was similar to that of the ML tree (previous section); only a few differences were observed and are indicated with asterisks in Figures 1, 2, and 3. The medians and 95% CIs of the estimated coalescence times of the major lineages are shown in Figure 3. It was estimated that GLB0, EAS, and JPN originated approximately 9,200 years ago (6,300–12,800 years ago), approximately 6,000 years ago (3,600–8,800 years ago), and approximately 3,900 years ago (2,200–6,000 years ago), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree of HTLV-1 with coalescence times. For this analysis, two constraints were applied: 1) Z46900 was designated as the outgroup; and 2) the mean and standard deviation of the coalescence time of HTLV-1c and the remainders of HTLV-1 lineages were designated as 60 and 6.1 thousand years ago. Coalescence times are shown for the nodes supported with posterior probabilities >70. The position of the isolate marked with an asterisk was remarkably different between the ML (Figs. 1, 2) and Bayesian trees.

Discussion

Our phylogenetic analyses indicated that three lineages of HTLV-1 coexist in Japan. Twenty-three of the 26 isolates sequenced from samples collected in this study were assigned to EAS or JPN lineages, both of which are probably endemic to East Asia. Two isolates from Kakeroma (14080806, 16080802) and one isolate from Hokkaido (01011035) were assigned to the global lineage, GLB1.

The earliest ancestors of modern humans likely arrived in Japan via the Korean Peninsula, expanded along the coastal areas of the archipelago from Honshu to Okinawa approximately 37,000 years ago, and colonized the north of Hokkaido approximately 23,000 years ago [23]. Because the arrival date of paleolithic people to Japan is much earlier than the estimated time of separation between cosmopolitan (HTLV-1a) and central African (HTLV-1b) subtypes (approximately 18,000 years ago, see Fig. 3), the introduction of HTLV-1 to Japan by paleolithic people is considered unlikely.

Palmer (2007) proposed the “Out of Sunda” hypothesis to explain the origins of the Jomon Japanese. During the last glacial period of the Pleistocene, Sundaland was covered by large areas of monsoon tropical forest and large expanses of savannah grassland vegetation on the coastal plains that may have supported a relatively large and dense human population. However, with the rapid rise in sea level at the end of the glacial period, a huge area of productive lowland (almost equal in size to India) was submerged. Therefore, some of the refugee populations could have left Sundaland, migrated eastward, and settled in the Japanese archipelago. Such migration and settlement may account for many or most of the Southeast Asian characteristics of the Japanese population and culture that are recognized today. Palmer [24] conjectured that the elevations in sea level leading to the “Out of Sunda” migrations occurred in stages, approximately 14,000, 11,500, and 7,500 years ago, and that subsequent refugees may have arrived in Japan at different times. While the first migrations to Japan are thought to have occurred approximately 10,000 years ago, a second wave of refugees may have entered Japan between 6,000 and 4,000 years ago, peaking at approximately 4,000 years ago. Our analyses suggest that the coalescence times of EAS (approximately 6,000 years ago) and JPN lineages (approximately 3,900 years ago) fall within the estimated periods of Sundaland refugee immigration into Japan. Thus, these Southeast Asian migrants arriving in Japan during the Jomon Period may have imported the EAS and JPN lineages. Subsequent local expansion of people within Japan may have caused genetic diversification in the EAS and JPN lineages. This hypothesis, however, is not consistent with conclusions made as a result of previous studies based on ethno-epidemiological data, which proposed that HTLV-I carriers in Japan are descendents of Paleo-Mongoloids who reached the Japan archipelago before the South-East Asian Mongoloids [13, 19].

Palmer [24] also proposed that the neolithic migrants to Japan could have “strandlooped” along the coast of Vietnam and China, or “island-hopped” via the Philippines, effectively using the Kuroshio current (northward) and the seasonal reversal of prevailing winds (both northward and southward). Several waves of migrations along different routes and different patterns of local expansion might have caused an uneven distribution of “transcontinental” and “Japanese” subgroups on the Japan archipelago as reported by Vidal et al. [18].

As discussed above, the origins of the two major lineages of HTLV-1 in Japan, EAS and JPN, appear to date back to the Jomon Period, whereas the other minor lineage, GLB1, might have been introduced to Japan by Africans accompanying European traders several centuries ago, during or after “The Age of Discovery.”

Methods

Source of HTLV-1 Proviral DNA

The following samples provided by the Joint Study on Predisposing Factors of ATL Development (JSPFAD) were used in the present study: four samples from Hokkaido (Hokkaido University Hospital), one from Iwate (Iwate Medical University), five from Kochi (Kochi Medical School Hospital), two from Hirado (Nagasaki University Hospital), two from Kumamoto (Kumamoto University Hospital), and six from Okinawa (Okinawa Kyodo Hospital). Furthermore, DNA was extracted from peripheral blood donated by six anonymous HTLV-1 carriers in the Kakeroma Island (Japan: Kagoshima Prefecture, Oshima County, Setouchi-cho) [25]. The analysis of samples donated by Kakeroma residents was approved by the ethics committee of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Japan (Approval No. 08061920).

Sequencing of the HTLV-1 Envelope Gene (env)

The entire envelope gene (5203–6669) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the four samples from Hokkaido, one from Iwate, five from Kochi, two from Hirado, two from Kumamoto, six from Kakeroma, and six from Okinawa (accession numbers: AB600204–AB600229). Reactions were performed in volumes of 20-µL including 1 µL (~50 ng) of the extracted DNA, 200 µM (final conc.) of dNTP mixture, 0.25 µM (final conc.) of the primer sets, 2 µL of 10× Ex Taq Buffer, and 0.5 U TaKaRa Ex Taq HS (TAKARA BIO Inc., Shiga, Japan). The primers TAATAGCCGCCAGTGGAAAG (5027–5046 bp: nucleotide positions referring to the J02029 sequence) and AGTCCTTGGAGGCTGAACG (6786–6768 bp) were used for all PCR reactions. The thermal conditions for PCR were as follows: 5-min denaturation at 95°C, 40 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, 100 s at 72°C, and a 10-min final extension at 72°C. Cycle sequencing reactions were performed using the ABI BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) and the following primers: TGGACAAGGGTCAGGAGTTT (5846-5827), ACCATGCCACCTATTCCCTA (5429-5448), CGTCTGTTCTGGGCAGCATA (6340-6321), and AACTGGACCCACTGCTTTG (6016-6034). The sequencing reaction products were subsequently loaded and analyzed on an ABI3130xl Sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). Complete envelope sequences (1467 bp in length) were assembled using DNA Baser v. 2.75.

Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Analysis

A total of 26 complete envelope gene sequences obtained in the present study and 62 sequences of HTLV-1 strains obtained from GenBank were aligned using ClustalW from MEGA software version 5.01 [26]. The best substitution model was chosen using Kakusan4 software [27] based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A tree search was conducted with the TreeFinder software (version October 2008) [28] using the output configuration file “whole_AIC_codonproportional_singlesearch.tl.” The obtained tree was improved using the likelihood ratchet method (batchfile contained in a Perl script package “Phylogears version 1.0.2009.10.16” [29]) using the command file, “whole_AIC_codonproportional_ratchetsearch_makestarttreesbytf;” the “nreps” and “percent” options were set at 100 and 25, respectively. Bootstrap resampling was performed using the batch file contained in the Phylogears package under the command file “whole_AIC_codonproportional_bootstrapanalysis,” with “nreps” set at 500. The obtained maximum likelihood tree (ML tree) was visualized with MEGA version 4.0 and re-rooted by designating a Simian T-Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 (STLV-1) isolate of Macaca tonkeana (Z46900) as the outgroup [20, 21].

Bayesian Analysis for Dating Coalescence of Major Lineages

For a model-based inference of the phylogeny, MrModeltest 2.3 [30] in conjunction with PAUP*4.0b10 [31] was used to examine the entire envelope dataset, applying hierarchical likelihood ratio tests (hLRTs) and AIC to choose a substitution model from the 24 considered by the program. A Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was then run with BEAST 1.5.4 [32], applying the best-fit model (GTR + I + G) selected by both the hLRT and AIC through MrModeltest. Two constraints were applied to this analysis: 1) Z46900 was designated as the outgroup; and 2) the mean and standard deviation of the coalescence time of HTLV-1c and the remainder of HTLV-1 lineages were set at 60 and 6.1 thousand years ago, respectively. We applied the second constraint because the Australo-Melanesian HTLV-1c, which is found only among non-Austronesian-language-speakers who are descendents of the earliest Melanesian/Australian settlers, most likely arose through interspecies transmission from simians to humans along the migratory path of the first humans migrating from Indonesia toward Melanesia [20, 21]. We assumed that HTLV-1c was separated from the rest of the primate T-cell lymphotropic viruses type 1 (PTLV-1) strains 60,000 years ago (95% confidence interval (CI): 50,000–70,000 years ago) because anthropological evidence suggests that the initial occupation of Sahul (the combined Australia-New Guinea land mass) occurred approximately 50,000–60,000 years ago [33].

The MCMC analysis ran for 150,000,000 generations, with sampling every 1,500 generations using the default parameter settings (except for the time constraint mentioned above). The initial 25,001 trees were removed, and a consensus Bayesian tree was constructed; its posterior probability, and the median and 95% CI of coalescence times for each node were estimated from 75,000 sampling events. Coalescence times of the major lineages, estimated by both the ML and Bayesian analyses, were shown on the Bayesian tree.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Junko Okumura, Masahiro Hashizume, Toshihiko Sunahara, and Hidefumi Fujii for their important comments and suggestions. The authors also thank staff members in all collaborating institutions, specifically Mr Makoto Nakashima, Ms Takako Akashi, and other technical members in the central office of the JSPFAD for efforts in sample processing and biological assays.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (20390186, 221S0001, 23659354, 23590800), Cooperative Research Grant (2009-E-1) of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, and the Global Center of Excellence Program at Nagasaki University. No sponsor, however, participated in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- 1.Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD, Gallo RC. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980; 77: 7415–7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verdonck K, González E, Van Dooren S, Vandamme AM, Vanham G, Gotuzzo E. Human T-lymphotropic virus 1: recent knowledge about an ancient infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7: 266–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinuma Y, Nagata K, Hanaoka M, Nakai M, Matsumoto T, Kinoshita KI, Shirakawa S, Miyoshi I. Adult T-cell leukemia: antigen in an ATL cell line and detection of antibodies to the antigen in human sera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1981; 78: 6476–6480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osame M, Usuku K, Izumo S, Ijichi N, Amitani H, Igata A, Matsumoto M, Tara M. HTLV-I associated myelopathy, a new clinical entity. Lancet 1986; 327(8488): 1031–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uchiyama T, Yodoi J, Sagawa K, Takatsuki K, Uchino H. Adult T-cell leukemia: clinical and hematologic features of 16 cases. Blood 1977; 50: 481–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okochi K, Sato H, Hinuma Y. A retrospective study on transmission of adult T cell leukemia virus by blood transfusion: seroconversion in recipients. Vox Sang 1984; 46: 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hino S, Yamaguchi K, Katamine S, Sugiyama H, Amagasaki T, Kinoshita K, Yoshida Y, Doi H, Tsuji Y, Miyamoto T. Mother-to-child transmission of human T-cell leukemia virus type-I. Jpn J Cancer Res 1985; 76: 474–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuver SO, Tachibana N, Okayama A, Shioiri S, Tsunetoshi Y, Tsuda K, Mueller NE. Heterosexual transmission of human T cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type I among married couples in southwestern Japan: an initial report from the Miyazaki Cohort Study. J Infect Dis 1993; 167: 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinuma Y, Komoda H, Chosa T, Kondo T, Kohakura M, Takenaka T, Kikuchi M, Ichimaru M, Yunoki K, Sato I, Matsuo R, Takiuchi Y, Uchino H, Hanaoka M. Antibodies to adult T-cell leukemia-virus-associated antigen (ATLA) in sera from patients with ATL and controls in Japan: a nation-wide sero-epidemiologic study. Int J Cancer 1982; 29: 631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanagihara R, Nerurkar VR, Garruto RM, Miller MA, Leon-Monzon ME, Jenkins CL, Sanders RC, Liberski PP, Alpers MP, Gajdusek DC. Characterization of a variant of human T-lymphotropic virus type I isolated from a healthy member of a remote, recently contacted group in Papua New Guinea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88: 1446–1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tajima K. Ethnic distribution of HTLV-1-associated diseases. Clinical Virology 1992; 20: 366–373 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashita M, Ishida T, Ohkura S, Miura T, Hayami M. Phylogenetic characterization of a new HTLV type 1 from the Ainu in Japan. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2001; 17: 783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonoda S, Li HC, Tajima K. Ethnoepidemiology of HTLV-1 related diseases: ethnic determinants of HTLV-1 susceptibility and its worldwide dispersal. Cancer Sci 2011; 102: 295–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandamme AM, Liu HF, Goubau P, Desmyter J. Primate T-lymphotropic virus type I LTR sequence variation and its phylogenetic analysis: compatibility with an African origin of PTLV-I. Virology 1994; 202: 212–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu HF, Goubau P, Van Brussel M, Van Laethem K, Chen YC, Desmyter J, Vandamme AM. The three human T-lymphotropic virus type I subtypes arose from three geographically distinct simian reservoirs. J Gen Virol 1996; 77: 359–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miura T, Yamashita M, Zaninovic V, Cartier L, Takehisa J, Igarashi T, Ido E, Fujiyoshi T, Sonoda S, Tajima K, Hayashi M. Molecular phylogeny of human T-cell leukemia virus type I and II of Amerindians in Colombia and Chile. J Mol Evol 1997; 44 Suppl 1: S76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Dooren S, Gotuzzo E, Salemi M, Watts D, Audenaert E, Duwe S, Ellerbrok H, Grassmann R, Hagelberg E, Desmyter J, Vandamme AM. Evidence for a post-Columbian introduction of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I in Latin America. J Gen Virol 1998; 79: 2695–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidal AU, Gessain A, Yoshida M, Mahieux R, Nishioka K, Tekaia F, Rosen L, De Thé G. Molecular epidemiology of HTLV type I in Japan: Evidence for two distinct ancestral lineages with a particular geographical distribution. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1994; 10: 1557–1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura T, Fukunaga T, Igarashi T, Yamashita M, Ido E, Funahashi S, Ishida T, Washio K, Ueda S, Hashimoto K, et al. Phylogenetic subtypes of human T-lymphotropic virus type I and their relations to the anthropological background. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91: 1124–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim F, de Thé G, Gessain A. Isolation and characterization of a new simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1 from naturally infected celebes macaques (Macaca tonkeana): complete nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic relationship with the Australo-Melanesian human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. J Virol 1995; 69: 6980–6993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandamme AM, Salemi M, Desmyter J. The simian origins of the pathogenic human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I. Trends Microbiol 1998; 6: 477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang YC, Hsu TY, Liu MY, Lin MT, Chen JY, Yang CS. Molecular subtyping of human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) by a nested polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the envelope gene: two distinct lineages of HTLV-I in Taiwan. J Med Virol 1997; 51: 25–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pope KO, Terrell JE. Environmental setting of human migrations in the circum-Pacific region. J Biogeogr 2008; 35: 1–21 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer E. Out of Sunda? Provenance of the Jomon Japanese. Japan Review 2007; 19: 47–75 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eguchi K, Fujii H, Oshima K, Otani M, Matsuo T, Yamamoto T. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) genetic typing in Kakeroma island, an island at the crossroads of the Ryukyuans and Wajin in Japan, providing further insights into the origin of the virus in Japan. J Med Virol 2009; 81: 1450–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28: 2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanabe AS. Kakusan: a computer program to automate the selection of a nucleotide substitution model and the configuration of a mixed model on multilocus data. Molecular Ecology Notes 2007; 7: 962–964 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jobb G, von Haeseler A, Strimmer K. TREEFINDER: a powerful graphical analysis environment for molecular phylogenetics. BMC Evol Biol 2004; 4: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Tanabe AS. (2008). “Phylogears version x.x.x”. Software distributed by the author at http://www.fifthdimension.jp/.

- 30.Nylander JAA. (May 22 2008). MrModeltest 2.3. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University. Available from http://www.abc.se/~nylander/

- 31.Swofford DL. (2003). PAUP*: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4. 0b10. Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA.

- 32.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol 2007; 7: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts RG, Jones R, Smith MA. Thermoluminescence dating of a 50,000-year-old human occupation site in northern Australia. Nature 1990; 345: 153–156 [Google Scholar]