Editor:

Ascites and chronic encephalopathy are common complications among patients with liver cirrhosis, for which abdominal paracenteses and lactulose use represent the standard therapeutic options. However, more-aggressive interventions to normalize blood ammonia and prevent irreversible neuronal damage are required in some cases. Traditional hemodialysis is an efficient method for removing serum ammonia, but the related risks of bleeding and hypotension limit its use in cirrhotic patients (1). Here, we report the case of such a patient, in whom the underlying chronic kidney disease did not require renal replacement therapy, but in whom severe recurrent encephalopathy and refractory ascites were successfully treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) at home for 10 months.

CASE REPORT

A 62-year-old man with ascites was referred to our department for stage 4 chronic kidney disease (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease glomerular filtration rate: 19.4 mL/min/1.73 m2). His medical history was significant for liver cirrhosis caused by infection with hepatitis B and C, as well as for colon and renal cell carcinoma treated with partial colectomy and right nephrectomy in May 2010. The patient went on to develop portal hypertension and ascites requiring frequent hospital admissions and treatment with diuretics, abdominal paracenteses, and albumin replacement. He was on a low-protein and low-sodium diet. While on oral furosemide 120 mg daily and spironolactone 100 mg daily, his diuresis was adequate, but 2 - 3 L abdominal fluid had to be drained every 2 - 3 months because of intolerable ascites. Before referral, this patient had already suffered 2 episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding requiring hospitalization. He had been forced to move from his own home, located on an island 8 hours from our hospital, because he was not fit to travel.

From December 2010, the patient’s clinical admissions became more frequent because of episodic hepatic encephalopathy. He was presenting with intolerable ascites, irritability, headaches, visual disturbances, and a fluctuating level of consciousness. His serum ammonia levels were repeatedly found to be 3 times the upper limit of normal (Table 1). His symptoms partially responded to removal of ascitic fluid, combined with multiple lactulose enemas and endogastric infusion of rifaximin or neomycin; however, he remained unable to care for himself, could not walk, and was experiencing poor sleep and appetite. Based on the patient’s life-threatening and laboriously-reversible encephalopathic series, we decided in March 2011 to insert a permanent peritoneal catheter.

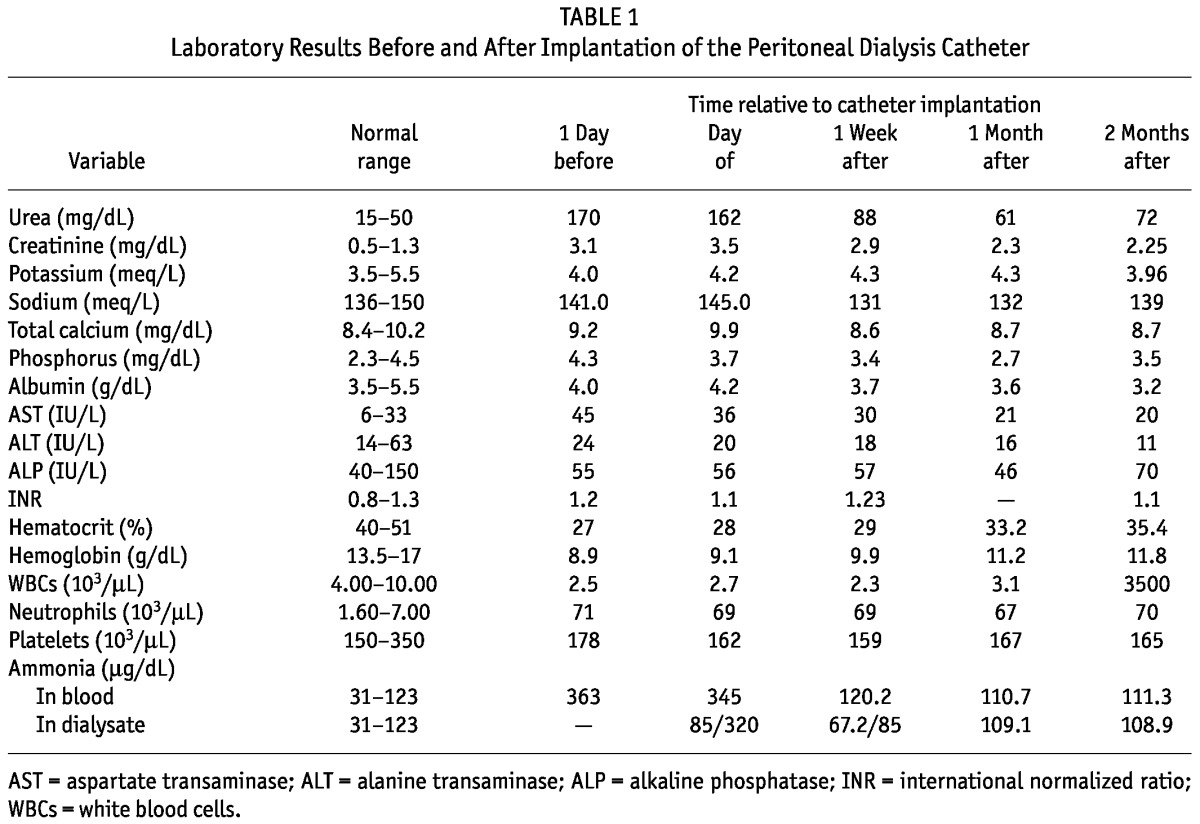

TABLE 1.

Laboratory Results Before and After Implantation of the Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter

At initiation of CAPD (1 day after catheter implantation), four 500-mL exchanges of 1.5% dextrose solution were performed. The exchange volume increased day after day, reaching at most 2000 mL and resulting in a dramatic improvement in the patient’s clinical status. Depending on the amount of the ascitic collection, the exchange frequency was reduced to 1 every 24 - 48 hours, allowing for “dry” days (Table 2). With the application of CAPD, ammonia was being removed through the dialysate (Figure 1), and hyperammonemia was controlled. Serum creatinine and urea declined, and hematocrit gradually rose (Table 1). Accumulation of ascites slowed, and the patient’s clinical condition improved significantly. He could eat and sleep normally and was again independent with self care.

TABLE 2.

Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) Record

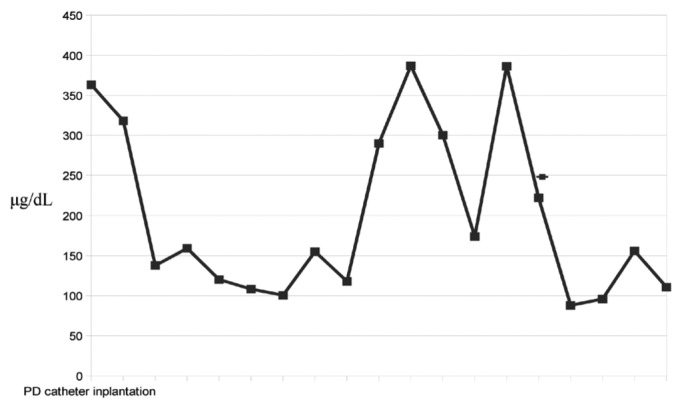

Figure 1.

— Blood ammonia levels in the first month after placement of the peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter. At initiation of PD, ammonia levels declined rapidly; when the patient’s appetite improved, ammonia levels increased; after the PD regimen was intensified, ammonia levels returned to normal values (range: 31 - 123 μg/dL).

The patient’s daily medications were modified to lactulose 60 mL, spironolactone 100 mg, furosemide 80 mg, omeprazole 20 mg, and tinzaparin 3500 IU. Human albumin 25% (100 mL) intravenously twice weekly and methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta (200 μg) subcutaneously every second week were administered for hypoalbuminemia and anemia correction respectively. Daily rifaximin 800 mg and nitrofurantoin 100 mg were also prescribed for prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The CAPD prescription was two 1.5-L exchanges of 1.5% dextrose daily. Optimal caloric intake was maintained by consuming vegetable proteins and carbohydrates. After the patient’s wife was trained to assist him with CAPD, he was discharged home in May 2011.

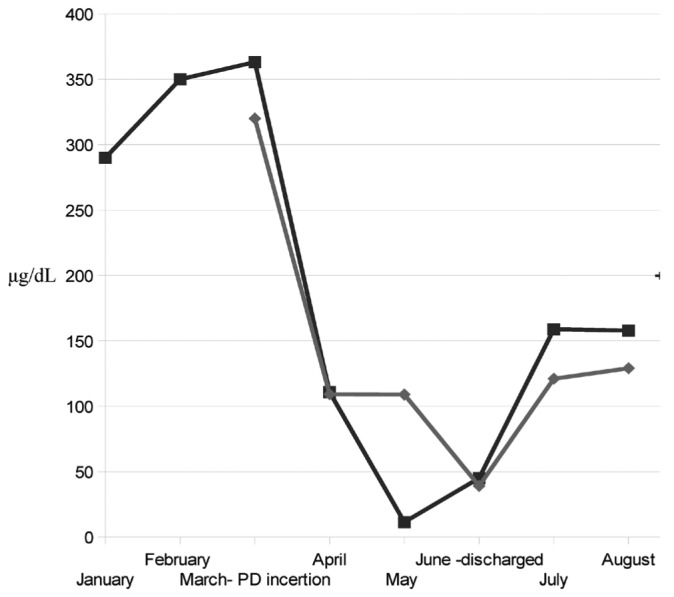

While the patient was treated with CAPD at home, fluid accumulation and blood ammonia levels were adequately controlled. Daily abdominal fluid ultrafiltration was approximately 1500 mL during the first week, gradually decreasing to 1000 mL. More frequent CAPD exchanges were used to treat excess ascitic fluid production or minor behavioral changes (Figure 2). Supplementation with oral albumin twice daily was used for persistently low serum albumin. Daily urine volume was 2 - 3 L, and serum creatinine remained stable.

Figure 2.

— Diagrammatic representation of ammonia levels in blood (closed squares) and dialysate (closed diamonds). The peritoneal catheter was placed in March, and the patient was discharged from hospital in May, when ammonia levels were fluctuating almost within normal values (range: 31 - 123 μg/dL).

Ten months after CAPD initiation, the patient lives at home on his island and is in good clinical condition, free of peritonitis episodes. He has had 1 episode of clinical deterioration, manifesting as consciousness disturbance, treated with four 1.5-L exchanges of 1.5% dextrose for 24 hours. No further hospitalization has been required.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report the application of home CAPD in a patient with fulminant hepatic failure and advanced chronic kidney disease. In the past, CAPD has been used (mostly in inpatient settings) for the treatment of hyperammonemia in newborn infants and young children with inborn errors of urea metabolism (2,3). It has also been successfully administered for the management of refractory ascites in cirrhotic adults requiring dialysis for end-stage renal disease (4). To our knowledge, there are no reports of CAPD applied at home to treat hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients without end-stage renal disease.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) has proved to be a successful treatment for our patient; however, the role of appropriate medication and nutritional support is not to be underestimated. Lactulose administration has been associated with reduced manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy and peritonitis (5), and vegetable proteins and pure albumin supplementation can improve protein wasting and nitrogen balance in cirrhotic patients. Combined with the foregoing measures, PD has produced symptomatic relief of ascites and continuous ammonia clearance (Figure 2) and has contributed to a significant improvement in the patient’s quality of life. Early titration of PD intensity, with concomitant monitoring of the patient’s clinical and cognitive status, allowed for adequate control of encephalopathy and minimized the episodes of encephalopathy relapse.

This case suggests that PD can be considered a treatment of choice for chronic cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemia. An important advantage of this method is the possibility that it offers for long-term optimization of mental status by allowing for continuous removal of ammonia. Notably, ammonia transport has been found to be lower in cirrhotic patients starting on PD. However, the peritoneal surface area expands, probably because of portal hypertension and the associated increase in the surface of the liver (4). A second advantage of PD is that it can contribute to maintaining a volume status appropriate for the patient while respecting hemodynamic stability and limiting the need for treatment at a medical facility (4,6). Furthermore, by elevating intra-abdominal hydrostatic pressure, PD dialysate opposes the accumulation of ascites and at the same time provides a source of calories, valuable for patients with liver cirrhosis, who may suffer from malnutrition and poor appetite (6). Finally, the peritoneal permeability enhancement described in the uremic milieu (7) and the evacuation of endotoxins (8) suspended in the peritoneal fluid may further ameliorate the clinical condition of the cirrhotic patient with concomitant chronic kidney disease.

To summarize, we present details of the care of a patient with end-stage liver disease and hepatic encephalopathy, who, despite not having end-stage renal disease, significantly benefited from the initiation of PD. The latter modality proved to be appropriate out patient management for lowering blood ammonia levels, preventing recurrence of encephalopathy episodes, and restoring the patient’s functional status and quality of life.

DISCLOSURES

There are no financial conflicts of interest. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

References

- 1. Howard CS, Teitelbaum I. Renal replacement therapy in patients with chronic liver disease. Semin Dial 2005; 18:212–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arbeiter AK, Kranz B, Wingen AM, Bonzel KE, Dohna-Schwake C, Hanssler L, et al. Continuous venovenous haemodialysis (CVVHD) and continuous peritoneal dialysis (CPD) in the acute management of 21 children with inborn errors of metabolism. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:1257–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Batshaw ML, Brusilow SW. Treatment of hyperammonemic coma caused by inborn errors of urea synthesis. J Pediatr 1980; 97:893–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Selgas R, Bajo MA, Del Peso G, Sánchez-Villanueva R, Gonzalez E, Romero S, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in the comprehensive management of end-stage renal disease patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites: practical aspects and review of the literature. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:118–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Afsar B, Elsurer R, Bilgic A, Sezer S, Ozdemir F. Regular lactulose use is associated with lower peritonitis rates: an observational study. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:243–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chaudhary K, Khanna R. Renal replacement therapy in end-stage renal disease patients with chronic liver disease and ascites: role of peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2008;28:113–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morgan AG, Terry SI. Impaired peritoneal fluid drainage in nephrogenic ascites. Clin Nephrol 1981; 15:61–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tarao K, So K, Moroi T, Ikeuchi T, Suyama T. Detection of endotoxin in plasma and ascitic fluid of patients with cirrhosis: its clinical significance. Gastroenterology 1977; 73:539–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]