Abstract

♦ Objectives: The present study evaluated the tool used to assess patients’ skills and the impact on peritonitis rates of a new multidisciplinary peritoneal dialysis (PD) education program (PDEP).

♦ Methods: After the University Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study, the educational and clinical records of PD patients were retrospectively analyzed in two phases. In phase I, an Objective Structured Assessment (OSA) was used during August 2008 to evaluate the practical skills of 25 patients with adequate Kt/V and no mental disabilities who had been on PD for more than 1 month. Test results were correlated with the prior year’s peritonitis rate. In phase II, the new PDEP, consisting of individual lessons, a retraining schedule, and group meetings, was introduced starting 1 September 2008. Age, sex, years of education, time on PD, number of training sessions, and peritonitis episodes were recorded. Statistical analyses used t-tests, chi-square tests, and Poisson distributions; a p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

♦ Results: In phase I, 25 patients [16 men, 9 women; mean age: 54 ± 15 years (range: 22 - 84 years); mean time on PD: 35 ± 30 months (range: 1 - 107 months)] were studied. The OSA results correlated with peritonitis rates: patients who passed the test had experienced significantly lower peritonitis rates during the prior year (p < 0.05). In phase II, after the new PDEP was introduced, overall peritonitis rates significantly declined (to 0.28 episodes/patient-year from 0.55 episodes/patient-year, p < 0.05); the Staphylococcus peritonitis rate also declined (to 0.09 episodes/patient-year from 0.24 episodes/patient-year, p < 0.05).

♦ Conclusions: The OSA is a reliable tool for assessing patients’ skills, and it correlates with peritonitis rates. The multidisciplinary PDEP significantly improved outcomes by further lowering peritonitis rates.

Key words: Objective structured assessment, therapeutic education, peritonitis rate

Peritonitis is a major complication and the main cause of peritoneal dialysis (PD) failure, severely affecting patient morbidity and mortality. Despite regularly updated guidelines from the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) on PD-related infections and their prevention and treatment (1-3), peritonitis continues to be a worrisome problem throughout the world (4-8).

Patient training is recognized to be very important in preventing this complication (9-11). The impact of patients’ knowledge about their illness on outcome is well known in diabetes and other chronic conditions (12,13). Education programs with a theoretical basis, using cognitive framing and motivational interviewing principles, are associated with improved outcomes (14-20). A multidisciplinary approach with a precise schedule—“therapeutic education” (11)—has became an important therapeutic tool (21,22). The ISPD guidelines (10) assert that a new PD education program (PDEP) may be evaluated by observing changes in peritonitis rates, but the value of individual evaluation at the end of a training period is still controversial (11). Chen et al. (23) found no correlation between post-training test scores and peritonitis rates. Russo et al. (24) proposed a theoretical questionnaire and a practical evaluation of patient performance using the Nurse Score Card as a checklist.

In an effort to lower the peritonitis incidence, we decided to change our PD training and retraining program and also our evaluation tool. We used questionnaires during training and a practical evaluation tool similar to the Objective Structured Clinical Assessment, first introduced by Harden et al. in the evaluation of medical students in 1975 (25) and today widely used for that purpose.

In the present study, we evaluated the tool used to assess patients’ skills and the impact on peritonitis rates of a new multidisciplinary PDEP.

METHODS

This retrospective analysis reviewed the educational and clinical records of patients on chronic PD at a Uruguayan PD center. The study was approved by the University Hospital Ethics Committee.

PHASE I

The center’s database was used, preserving confidentiality. Regular surveillance and treatment of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriers and antibiotic prophylaxis for exit-site infections has been routine since 2002; staff members made no changes to those measures. In August 2008, 25 patients with adequate weekly Kt/V (≥1.8) and without mental disabilities who had been on PD for at least 1 month were studied after they gave informed consent. Age, sex, time on PD, years of formal education, and peritonitis episodes (date and causative micro-organisms) were recorded, and prior-year peritonitis rates were calculated.

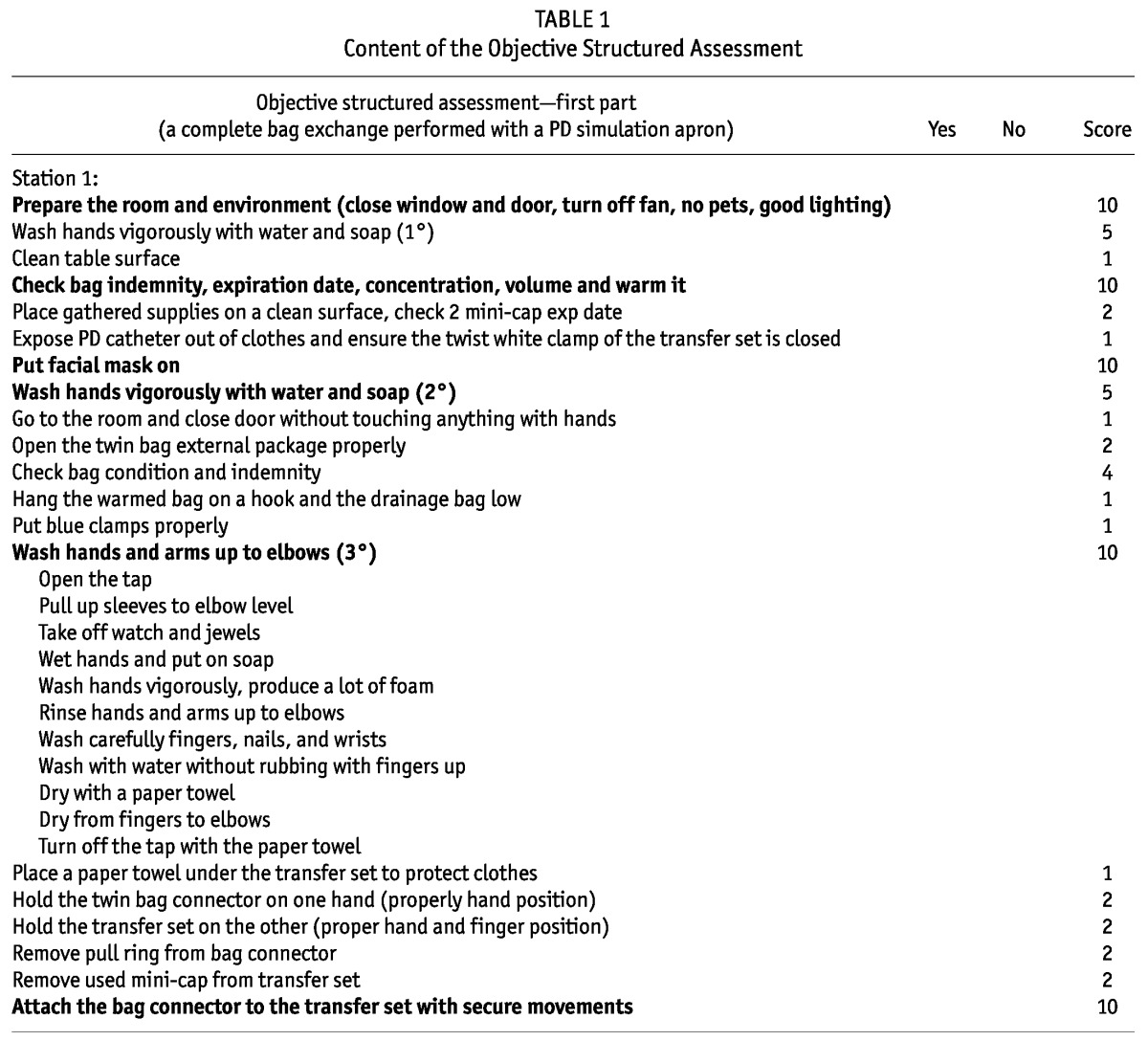

A new tool for evaluating the patients’ skills was introduced in August 2008: PD bag exchange methods and troubleshooting questions were evaluated using an Objective Structured Assessment (OSA) based on the Objective Structured Clinical Assessment. The OSA consists of 6 “stations” (Table 1) and 15 “key” steps scored at 10 points (5%) each, so that if any key step is incorrectly performed or answered, the final score is 95% or less. Patient and partners on training who were completing the OSA were unaware of PD nurse observation so as to preserve self-confidence and reduce stress. An “acceptable” score was more than 95% correct answers. After an unacceptable score, retraining would begin, and testing would be repeated until a perfect score was achieved.

TABLE 1.

Content of the Objective Structured Assessment

PHASE II

The main goal of the PDEP was to lower peritonitis rates. From 1 September 2008 to 31 December 2010, 31 new patients (at least 1 month on treatment) were admitted and trained using a new multidisciplinary PDEP according to ISPD recommendations (10,11). Sex, age, years of formal education, number of training sessions, time on PD during the study period, peritonitis episodes, and causative micro-organisms were recorded, and peritonitis rates were calculated according to ISPD guidelines (13). For patients incapable of performing the bag exchange (because of blindness, motor disabilities, or OSA failure), a partner was designated by the patient. In those cases (n = 7), the partner was trained, and the partner’s educational data were recorded for the study.

The new PDEP consists of individual (“one-on-one”) lessons delivered in a comfortable setting and providing printed material and troubleshooting information and practice of PD exchanges using a PD apron. Beginning with the second session and throughout the course, a brief oral questionnaire about the material taught in the previous session is administered; wrong answers are reviewed, with repetition of the entire session if necessary. The number of sessions, their duration, and the materials used are adapted to the personalities and cultural backgrounds of the patients and partners, and sessions continue until participants answer the pre-session questionnaires and complete the OSA perfectly. Only after participants pass the OSA are they authorized to perform PD independently at home.

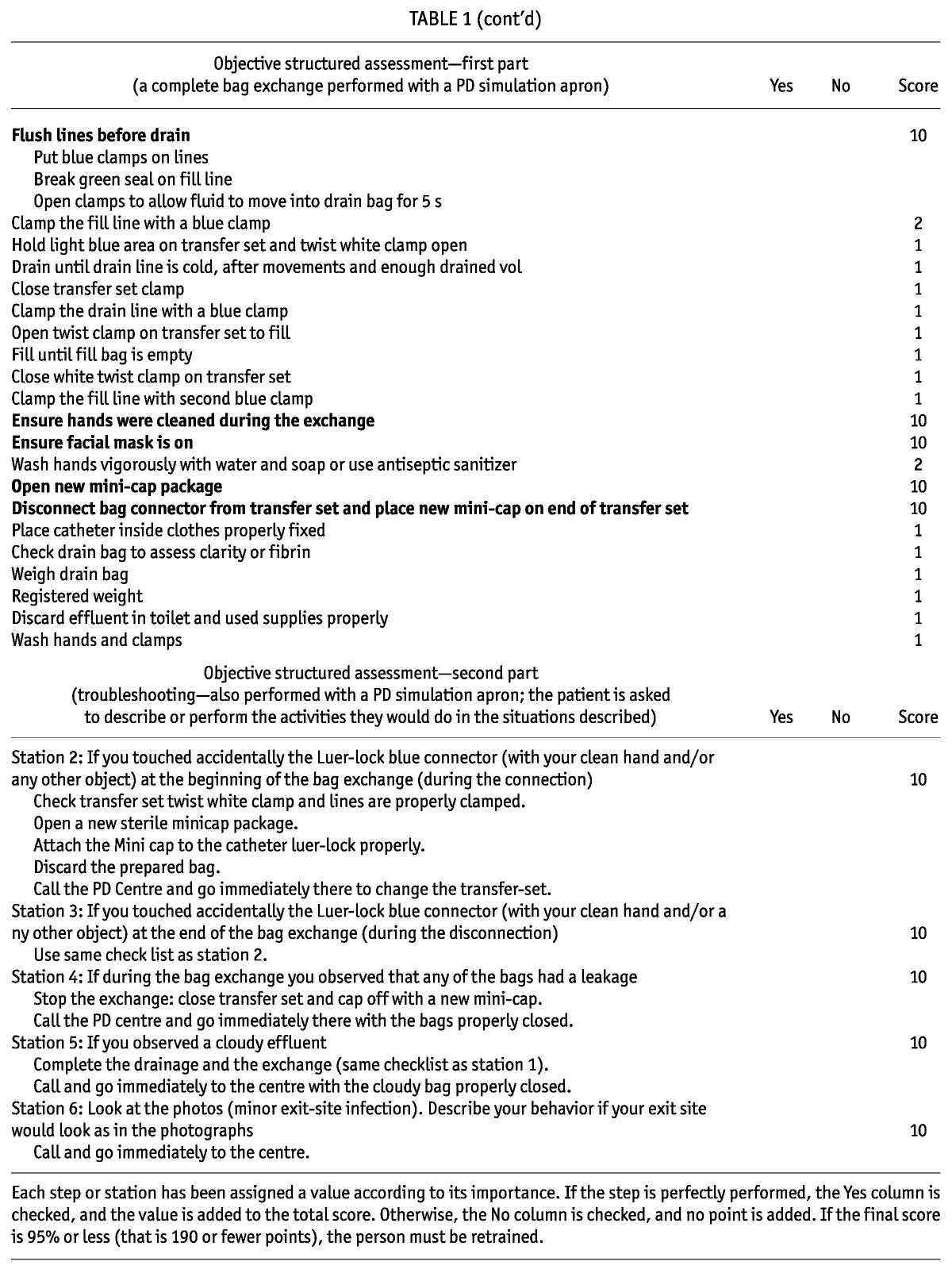

The 8 lessons of the new PDEP (Table 2) are delivered in a minimum of 5 sessions, each session being about 2 hours long. Training is usually provided at the outpatient clinic before catheter placement, but if the patient needs to begin PD urgently, it is provided during hospitalization. The PD nurse, nutritionist, and nephrologist actively participate. In special circumstances, a psychologist or social worker also participates. The PD nurse visits the homes and work spaces of the patients; if environmental conditions are inadequate, the social worker helps to improve them (as usual).

TABLE 2.

Lessons in the New Peritoneal Dialysis Education Program

At the end of the standard training, participants’ skills are evaluated using the OSA as previously described, and if the OSA score does not reach 95%, training is restarted with an in-depth review of the “failing” items. After 2 more sessions, a new OSA is performed until a perfect score was achieved. The PD nurse also goes to patients’ homes the day they first begin bag exchanges. In addition, patients twice annually attend a retraining session, and at each monthly visit, exit-site care and safe bag exchange procedures are reinforced. Twice yearly, a workshop is held to discuss diet, physical exercise, and general well-being, with the whole team and the patients exchanging ideas. At each workshop, the “safe bag exchange in different environments” topic is discussed. If needed, motivational interviewing principles (express empathy, develop discrepancy, avoid argumentation, roll with resistance, and support self-efficacy) are used by the care team to help patients make lifestyle changes and to take better care of themselves (16).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Results are given as means with standard deviations and medians with ranges. Differences between the groups in age, years of formal education, and number of training sessions were evaluated using the Student t-test. Differences in the prevalence of older patients were evaluated using the chi-square test. Poisson distributions were used to assess differences in peritonitis rates between the groups. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

PHASE I

Of the 25 patients on PD at August 2008 [16 men, 9 women; mean age: 54 ± 15 years (range: 22 - 84 years); mean time on PD: 35 ± 30 months (range: 1 - 107 months)], 22 obtained an acceptable score on the OSA, and 3 had an unacceptable score. Results correlated with the prior year’s peritonitis rate. Those who passed the OSA had lower overall, S. aureus, and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CNS) peritonitis rates in the preceding year (overall: 0.24 episodes/patient-year; CNS: 0.1 episodes/patient-year) than did those who failed the OSA (overall and CNS: 0.67 episodes/patient-year; Poisson p < 0.05).

PHASE II

The 3 patients who did not achieve acceptable scores on the OSA were retrained until their scores were acceptable. Patients who started on PD from 1 September 2008 to 31 December 2010 [31 patients: 15 men, 16 women; mean age: 55 ± 16 years (range: 20 - 80 years)] were trained using the new PDEP and were evaluated using the OSA. Only 1 patient who did not achieve an acceptable score on the OSA after 20 sessions was advised to find a partner to perform the exchange. That partner’s age, years of formal education, and performance were considered in the present study.

The mean number of sessions required to achieve the objective was 8 (range: 5 - 18). After the initial standard training, 19 participants achieved an acceptable score [group I: 14 patients, 5 partners; mean sessions: 6 (range: 5 - 8)]; 12 participants (group II: 10 patients, 2 partners) needed more sessions because their scores on the OSA were unacceptable after the 8 initial sessions. The group II patients and partners received a mean of 13 sessions (range: 10 - 18 sessions). Compared with group I, group II included more participants older than 65 years of age (χ2 p < 0.05). Mean age was significantly lower in group I (46 ± 11 years) than in group II (70 ± 11 years, t-test p < 0.05), and years of formal education were significantly greater in group I (12.3 ± 3.9 years) than in group II (9.1 ± 3.3 years).

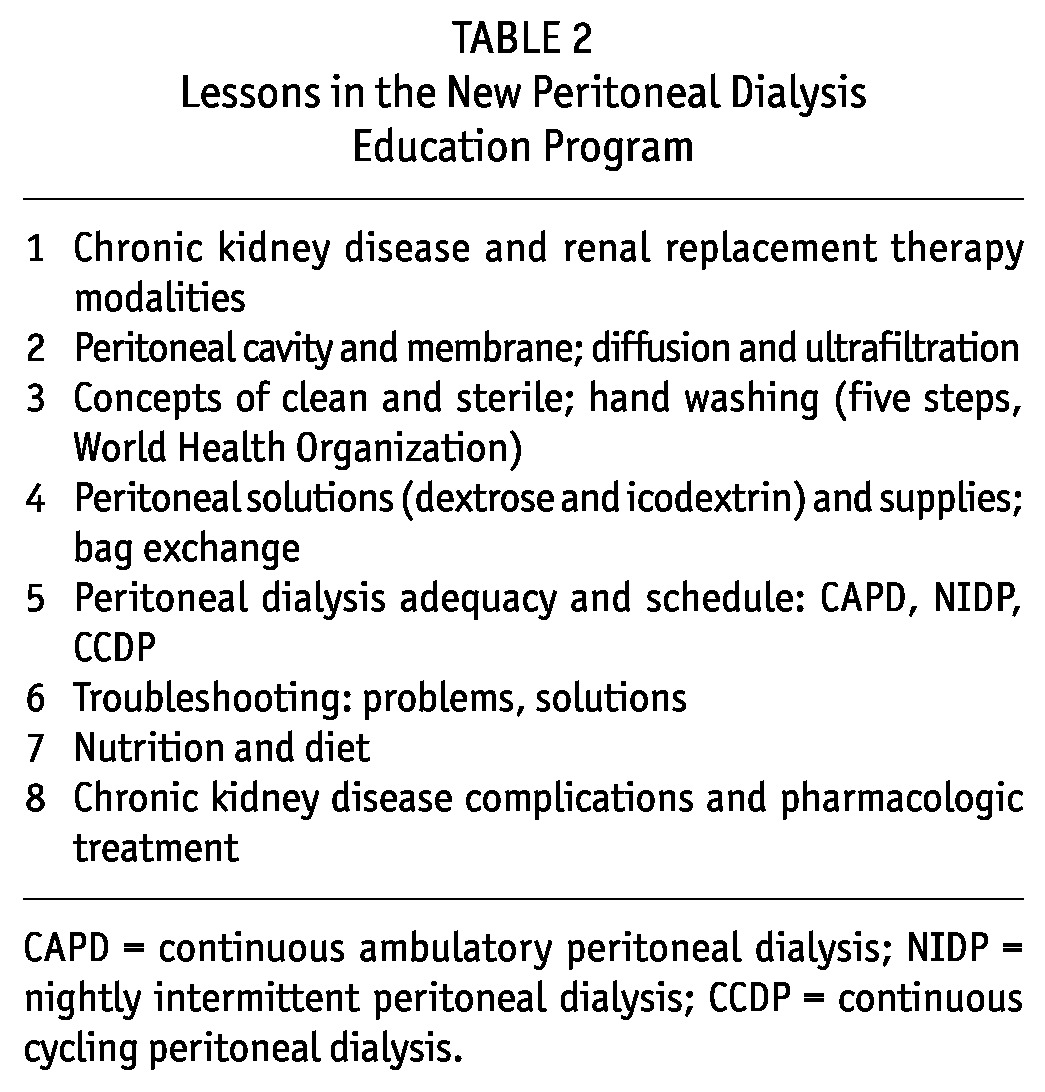

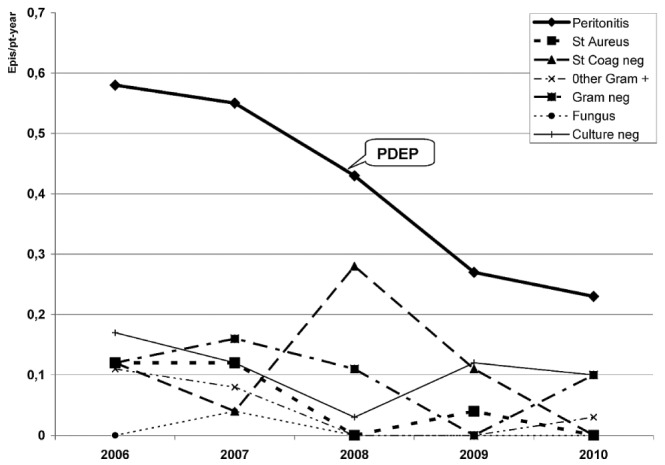

During the next 2 years, peritonitis rates were not different between the groups (overall rate—group I: 0.29 episodes/patient-year; group II: 0.1 episodes/patient-year; CNS rate—group I: 0.14 episodes/patient-year; group II: 0.1 episodes/patient-year; p = nonsignificant). The 7 patients who had a partner to perform the bag exchange did not experience any peritonitis episodes during the study period; the other 24 patients experienced peritonitis episodes (overall and individual micro-organisms) that were recorded and analyzed in two 2-year periods: before the PDEP (from 1 September 2006 to 31 August 2008) and after the PDEP (1 September 2008 to 31 August 2010). Peritonitis rates declined significantly to 1 episode in 43 patient-months (0.28 episodes/patient-year) after the PDEP, from 1 episode in 22 patient-months (0.55 episodes/patient-year) before the PDEP (p < 0.05). Rates of S. aureus and CNS peritonitis also significantly declined to 1 episode in 128 patient-months (0.09 episodes/patient-year) after the PDEP from 1 episode in 51 patient-months (0.24 episodes/patient-year) before the PDEP (p < 0.05). The S. aureus peritonitis rate declined to 0.02 episodes/patient-year from 0.04 episodes/patient-year before the PDEP, and the CNS peritonitis rate declined to 0.07 episodes/patient-year after the PDEP from 0.20 episodes/patient-year before the PDEP (p < 0.05). Annual overall peritonitis rates at the PD center declined to 0.23 episodes/patient-year in 2010 from 0.58 episodes/patient-year in 2007; CNS peritonitis rates declined accordingly (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

— Infections before and after implementation of the new peritoneal dialysis education program (PDEP), 1 September 2008.

DISCUSSION

PATIENT TRAINING

The training of PD patients is extremely important and may affect technique success and clinical outcomes (23). Therapeutic education has been considered a key factor in PD outcomes (23,24,26). Ballerini and Paris (20) recommend that the nephrology team acquire a new professional biopsychosocial educational model: a patient may “know” procedures and self-care practices, but may not be “motivated” enough to make the lifestyle changes necessary to achieve them. Therefore, our new PDEP used “motivational interviewing principles” (16), and patients were supported by a psychologist if necessary.

Nurse training experience must also be taken into account (11,26-28). Elderly patients need more time to learn, but may achieve the same or better results (29). We observed that elderly patients (>65 years of age) needed more training sessions to achieve the necessary skills to perform home PD, but they eventually achieved similarly good results. We therefore emphasize the importance of personalized training that considers individual circumstances and that supports self-efficacy (helping to increase the patients’ perception of their capability to cope with difficulties and to succeed).

PATIENT KNOWLEDGE EVALUATION

Chen et al. (23) did not find a correlation between results on a post-training test and peritonitis rates, but demonstrated a correlation with years of formal education, suggesting that previous education prepared the patients to answer written questions but not necessarily to perform the needed manual skills. Kazancioglu (30) found a correlation between outcome and home-visit skills evaluation and environment.

We decided to use two evaluation tools suggested by Russo and colleagues (24): a cognitive evaluation of the patients’ understanding and a practical evaluation of the patients’ skills. We used those tools during training, with the immediate reinforcement of additional training sessions as necessary. The OSA evaluates only practical skills (bag exchange and troubleshooting behavior), a method that was inspired by the Objective Structured Clinical Assessment proposed by Harden et al. (25).

Our finding that participants who obtained an acceptable score on their first OSA had had a lower peritonitis rate in the preceding year than did participants whose first OSA score was unacceptable (p < 0.05) validates the OSA as a measure. The method has the advantage that skills are assessed using a predefined marking system in a “checklist” (31), helping the observer to pay attention to every single detail. However, final validation of the OSA requires further study in a different population.

In an international survey on training, Bernardini et al. (11) did not find any correlation between length of training and outcome. On the basis of our results, we believe that length of training depends mostly on individual patient characteristics. Training must be personalized, and results must be seen in the unique biopsychosocial circumstances of each participant.

PD THERAPEUTIC EDUCATION: IMPACT ON OUTCOMES

Our PDEP is based on cognitive philosophy and psychological theories of learning that focus on patient empowerment and autonomy motivation to improve communication and facilitate behavioral change (16,22). Peritonitis rates have been used in the quality evaluation of PD programs (32-34). In Uruguay, a national registry of PD infections (active since 2004) demonstrated that the main causative micro-organism is methicillin-resistant CNS; the national overall peritonitis rate is 0.5 episodes/patient-year (35). In the present study, the overall peritonitis rate showed significant improvement in the 2 years after the PDEP began compared with the 2 years before, declining to 0.28 episodes/patient-year from 0.55 episodes/patient-year. A constant decline in the overall and CNS peritonitis rates was observed between 2008 and 2010 (Figure 1).

We consider that our results represent a positive evaluation of the new PDEP. We hope that this education program, which can be summarized as “training until a perfect OSA test is achieved by a highly motivated person,” can be easily reproduced by other PD teams. As long as the educational approach described here is introduced, with motivational interviewing and the OSA test, our results should be replicable in other facilities.

CONCLUSIONS

The OSA is a reliable tool to assess technical skills (PD bag exchange and troubleshooting), and our new PDEP significantly lowered peritonitis rates, especially those attributed to CNS infection.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, Boeschoten E, Gupta A, Holmes C, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2005 update. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25:107–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, Bernardini J, Figueiredo AE, Gupta A, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:393–423 [Erratum in: Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:512] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Piraino B, Bernardini J, Bender FH. An analysis of methods to prevent peritoneal dialysis catheter infections. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:437–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown MC, Simpson K, Kerssens JJ, Mactier RA. on behalf of the Scottish Renal Registry. Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis rates and outcomes in a national cohort are not improving in the post-millennium (2000-2007). Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:639–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moraes TP, Pecoits-Filho R, Ribeiro SC, Rigo M, Silva MM, Teixeira PS, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in Brazil: twenty-five years of experience in a single center. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29:492–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ghali JR, Bannister KM, Brown FG, Rosman JB, Wiggins KJ, Johnson DW, et al. Microbiology and outcomes of peritonitis in Australian peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:651–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mactier R. Peritonitis is still the Achilles’ heel of peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29:262–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan A, Rigatto C, Verrelli M, Komenda P, Mojica J, Roberts D, et al. High rates of mortality and technique failure in peritoneal dialysis patients after critical illness. Perit Dial Int 2012; 32:29–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ersoy FF. Improving technique survival in peritoneal dialysis: what is modifiable? Perit Dial Int 2009; 29(Suppl 2):S74–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bernardini J, Price V, Figueiredo A. on behalf of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) Nursing Liaison Committee. Peritoneal dialysis patient training, 2006. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:625–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernardini J, Price V, Figueiredo A, Riemann A, Leung D. International survey of peritoneal dialysis training programs. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:658–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ko SH, Song KH, Kim SR, Lee JM, Kim JS, Shin JH, et al. Long-term effects of a structured intensive diabetes education programme (SIDEP) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus—a 4-year follow-up study. Diabet Med 2007; 24:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease: a systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:1641–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trento M, Gamba S, Gentile L, Grassi G, Miselli V, Morone G, et al. Rethink Organization to iMprove Education and Outcomes (ROMEO): a multicenter randomized trial of lifestyle intervention by group care to manage type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010; 33:745–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner TC, Campbell MJ, Carey ME, Cradock S, et al. on behalf of the Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed Collaborative. Effectiveness of the Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008; 336:491–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manns BJ, Taub K, Vanderstraeten C, Jones H, Mills C, Visser M, et al. The impact of education on chronic kidney disease patients’ plans to initiate dialysis with self-care dialysis: a randomized trial. Kidney Int 2005; 68:1777–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fox C, Kohn LS. The importance of patient education in the treatment of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008; 74:1114–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, Barré P, Takano T, Soroka S, et al. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int 2008; 74:1178–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ballerini L, Paris V. Nosogogy: when the learner is a patient with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl 2006; (103):S122–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neville A, Jenkins J, Williams JD, Craig KJ. Peritoneal dialysis training: a multisensory approach. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(Suppl 3):S149–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Aikens JE, Krein SL, Fitzgerald JT, Nwankwo R, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of an empowerment-based self-management consultant intervention: results of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Ther Patient Educ 2009; 1:3–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen TW, Li SY, Chen JY, Yang WC. Training of peritoneal dialysis patients—Taiwan’s experiences. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28(Suppl 3):S72–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Russo R, Manili L, Tiraboschi G, Amar K, De Luca M, Alberghini E, et al. Patient re-training in peritoneal dialysis: why and when it is needed. Kidney Int Suppl 2006; (103):S127–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harden RM, Stevenson M, Downie WW, Wilson GM. Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination. Br Med J 1975; 1:447–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chow KM, Szeto CC, Law MC, Fun Fung JS, Li PKT. Influence of peritoneal dialysis training nurses’ experience on peritonitis rates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2:647–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang Z, Xu R, Zhuo M, Dong J. Advanced nursing experience is beneficial for lowering the peritonitis rate in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2012; 32:60–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu R, Zhuo M, Yang Z, Dong J. Experiences with assisted peritoneal dialysis in China. Perit Dial Int 2012; 32:94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim WH, Dogra GK, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Johnson DW. Compared with younger peritoneal dialysis patients, elderly patients have similar peritonitis-free survival and lower risk of technique failure, but higher risk of peritonitis-related mortality. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:663–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kazancioglu R, Ozturk S, Ekiz S, Yucel L, Dogan S. Can using a questionnaire for assessment of home visits to peritoneal dialysis patients make a difference to the treatment outcome? J Ren Care 2008; 34:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith LJ, Price DA, Houston IB. Objective structured clinical examination compared with other forms of student assessment. Arch Dis Child 1984; 59:1173–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finkelstein FO, Ezekiel OO, Raducu R. Development of a peritoneal dialysis program. Blood Purif 2011; 31:121–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prowant BF. Determining if characteristics of peritoneal dialysis home training programs affect clinical outcomes: not an easy task. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:643–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bordin G, Casati M, Sicolo N, Zuccherato N, Eduati V. Patient education in peritoneal dialysis: an observational study in Italy. J Ren Care 2007; 33:165–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gadola L, Orihuela L, Pérez D, Gómez T, Solá L, Chifflet L, et al. Peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients in Uruguay. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:232–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]