Abstract

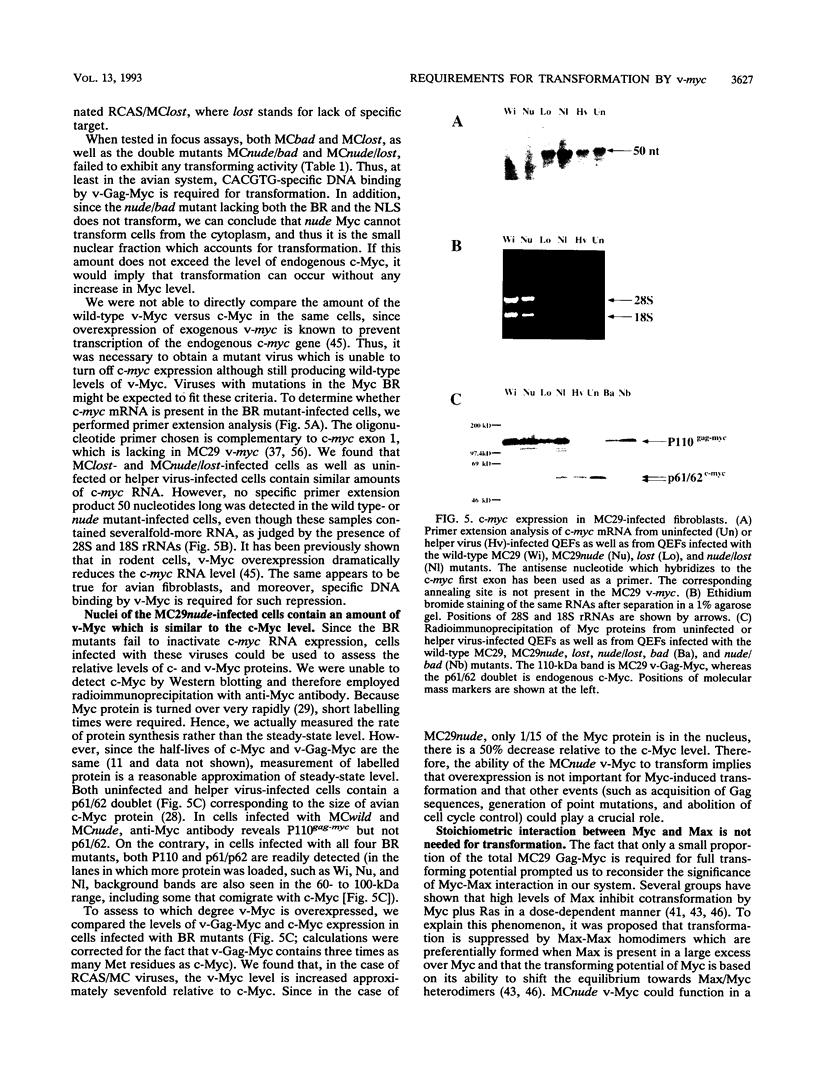

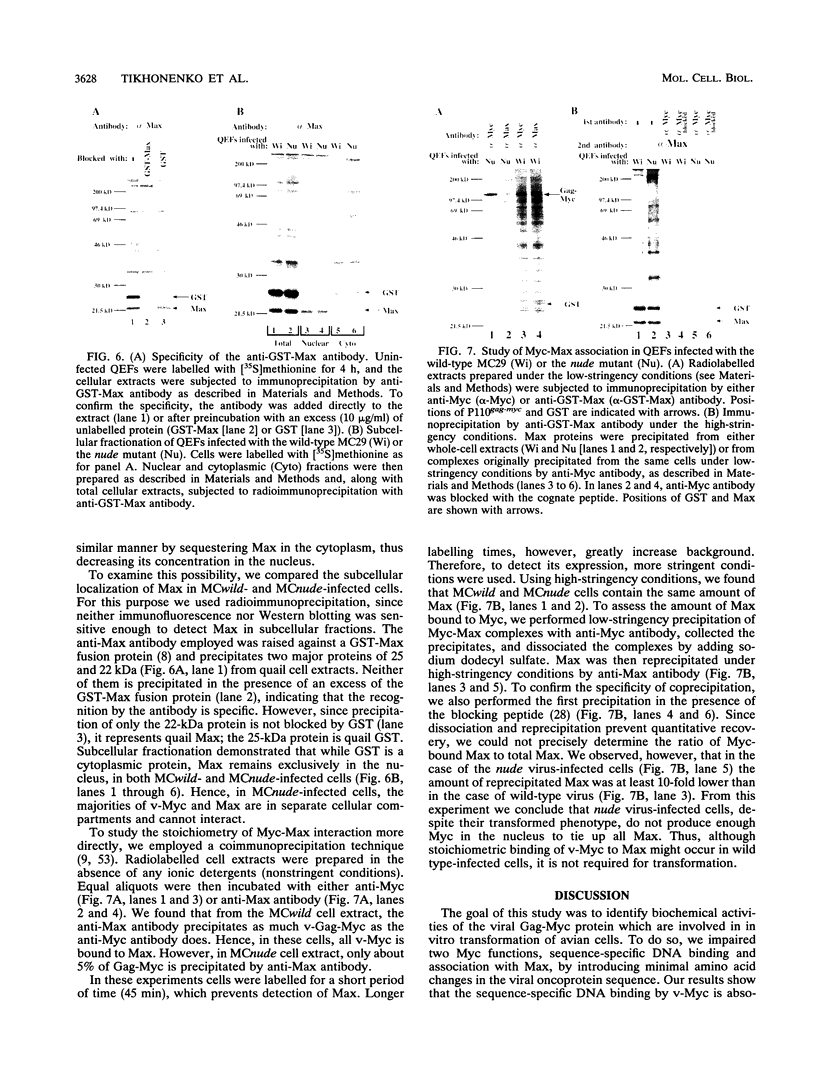

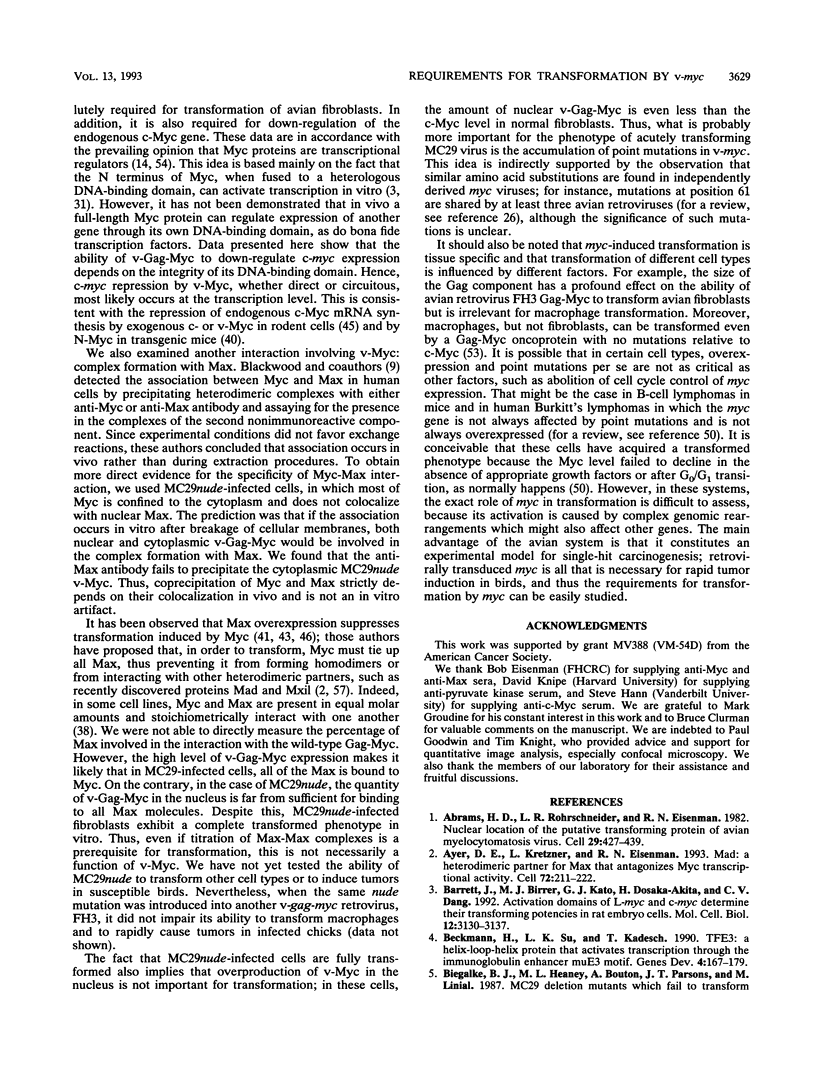

The cellular proto-oncogene c-myc can acquire transforming potential by a number of different means, including retroviral transduction. The transduced allele generally contains point mutations relative to c-myc and is overexpressed in infected cells, usually as a v-Gag-Myc fusion protein. Upon synthesis, v-Gag-Myc enters the nucleus, forms complexes with its heterodimeric partner Max, and in this complex binds to DNA in a sequence-specific manner. To delineate the role for each of these events in fibroblast transformation, we introduced several mutations into the myc gene of the avian retrovirus MC29. We observed that Gag-Myc with a mutated nuclear localization signal is confined predominantly in the cytoplasm and only about 5% of the protein could be detected in the nucleus (less than the amount of endogenous c-Myc). Consequently, only a small fraction of Max is associated with Myc. However, cells infected with this mutant exhibit a completely transformed phenotype in vitro, suggesting that production of enough v-Gag-Myc to tie up all cellular Max is not needed for transformation. While the nuclear localization signal is dispensable for transformation, minimal changes in the v-Gag-Myc DNA-binding domain completely abolish its transforming potential, consistent with a role of Myc as a transcriptional regulator. One of its potential targets might be the endogenous c-myc, which is repressed in wild-type MC29-infected cells. Our experiments with MC29 mutants demonstrate that c-myc down-regulation depends on the integrity of the v-Myc DNA-binding domain and occurs at the RNA level. Hence, it is conceivable that v-Gag-Myc, either directly or circuitously, regulates c-myc transcription.

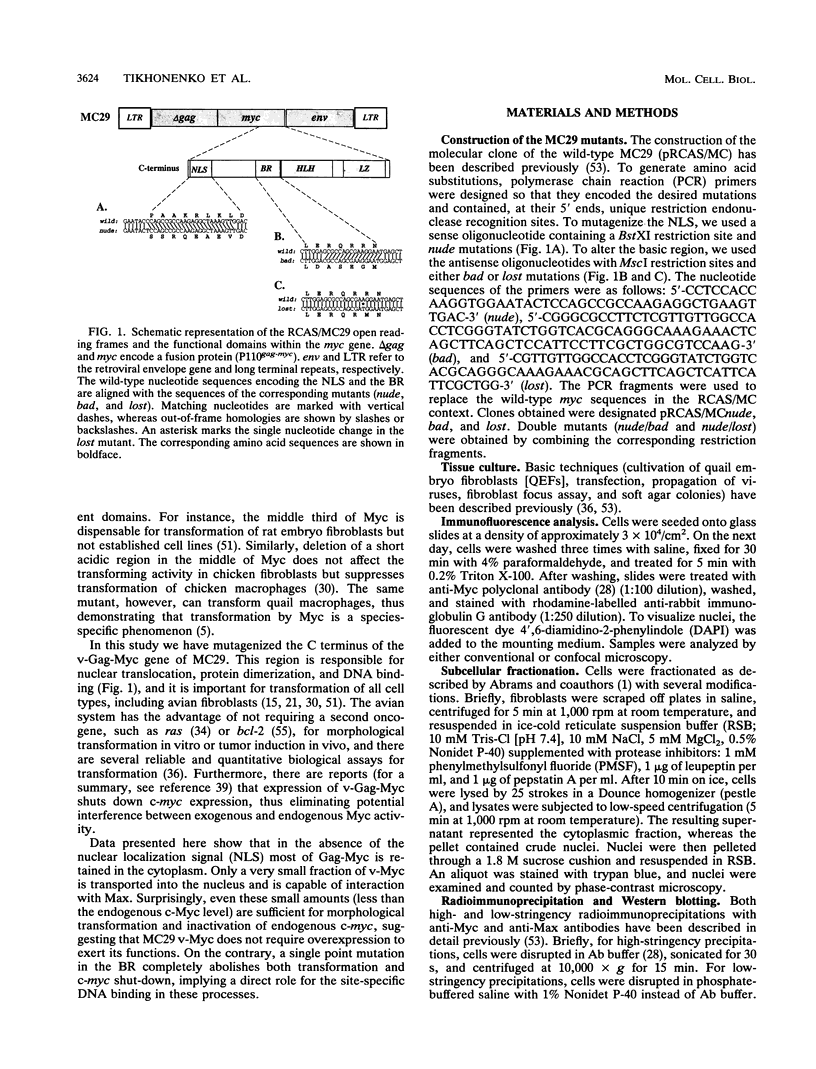

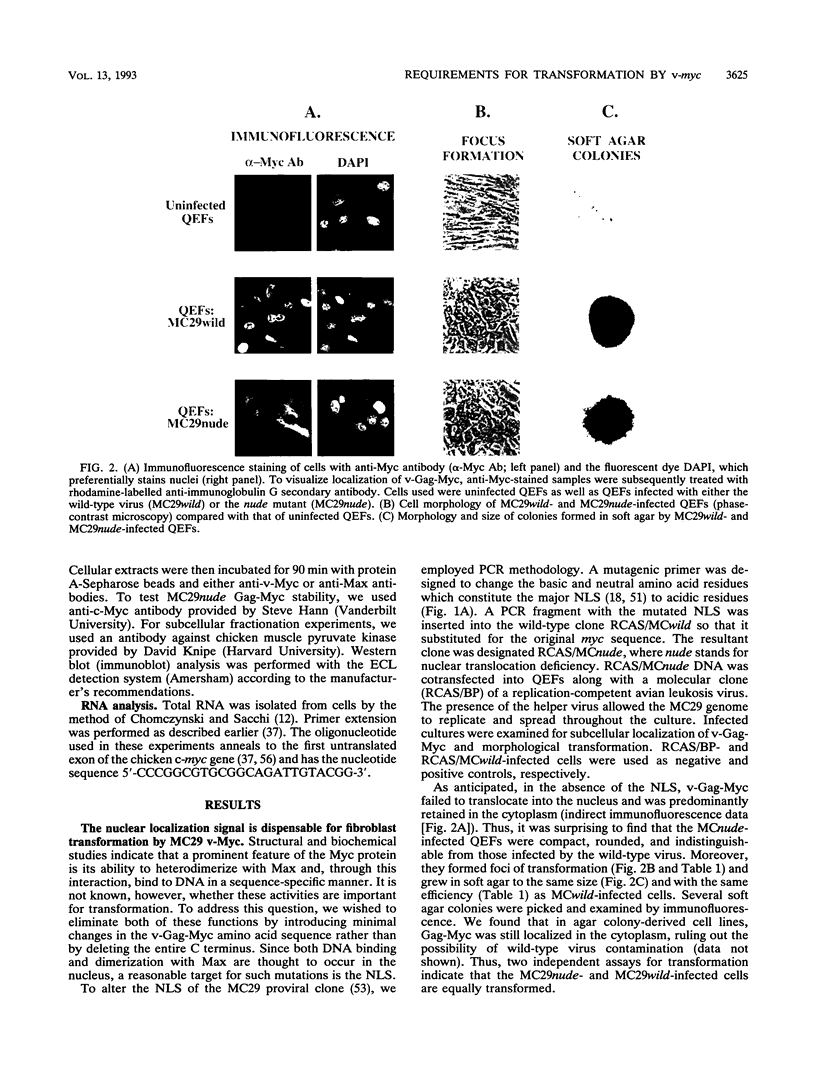

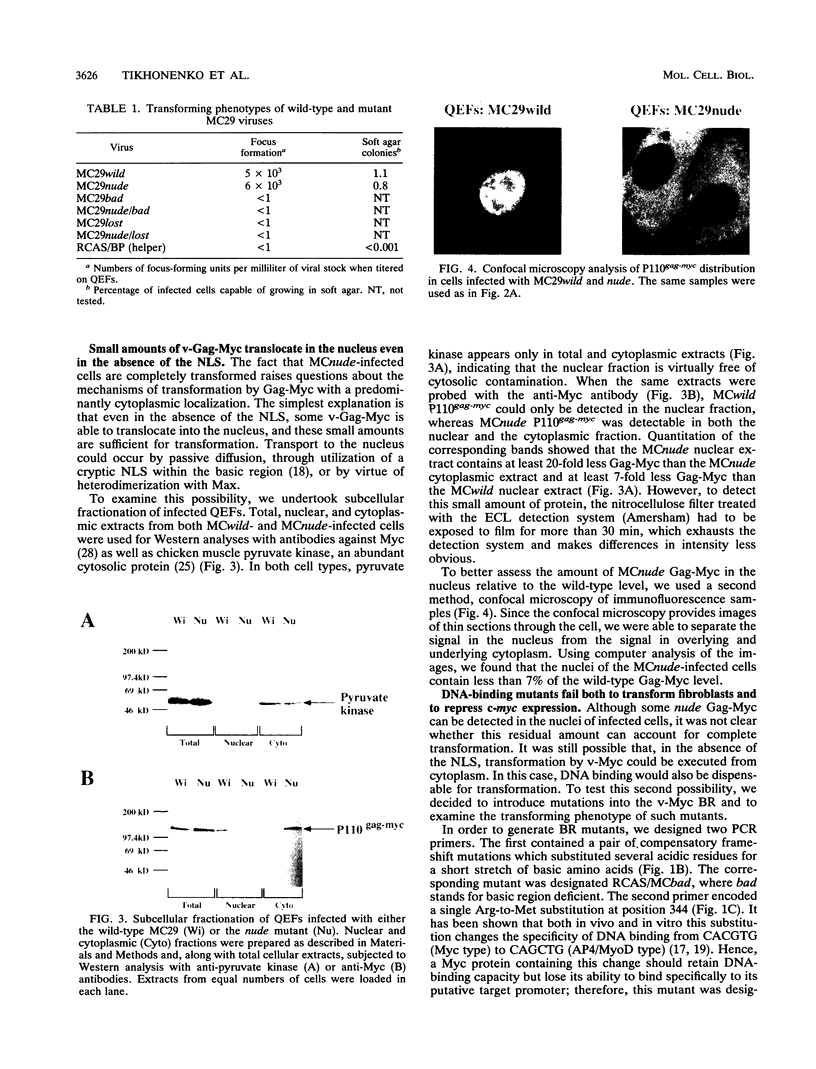

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abrams H. D., Rohrschneider L. R., Eisenman R. N. Nuclear location of the putative transforming protein of avian myelocytomatosis virus. Cell. 1982 Jun;29(2):427–439. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer D. E., Kretzner L., Eisenman R. N. Mad: a heterodimeric partner for Max that antagonizes Myc transcriptional activity. Cell. 1993 Jan 29;72(2):211–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J., Birrer M. J., Kato G. J., Dosaka-Akita H., Dang C. V. Activation domains of L-Myc and c-Myc determine their transforming potencies in rat embryo cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Jul;12(7):3130–3137. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann H., Su L. K., Kadesch T. TFE3: a helix-loop-helix protein that activates transcription through the immunoglobulin enhancer muE3 motif. Genes Dev. 1990 Feb;4(2):167–179. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bister K., Jansen H. W. Oncogenes in retroviruses and cells: biochemistry and molecular genetics. Adv Cancer Res. 1986;47:99–188. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell T. K., Kretzner L., Blackwood E. M., Eisenman R. N., Weintraub H. Sequence-specific DNA binding by the c-Myc protein. Science. 1990 Nov 23;250(4984):1149–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.2251503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood E. M., Eisenman R. N. Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc. Science. 1991 Mar 8;251(4998):1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.2006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood E. M., Lüscher B., Eisenman R. N. Myc and Max associate in vivo. Genes Dev. 1992 Jan;6(1):71–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M., Davis R. W. Yeast centromere binding protein CBF1, of the helix-loop-helix protein family, is required for chromosome stability and methionine prototrophy. Cell. 1990 May 4;61(3):437–446. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90525-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Biegalke B. J., Eisenman R. N., Linial M. L. FH3, a v-myc avian retrovirus with limited transforming ability. J Virol. 1989 Dec;63(12):5092–5100. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5092-5100.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987 Apr;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. D. The myc oncogene: its role in transformation and differentiation. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:361–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collum R. G., Alt F. W. Are myc proteins transcription factors? Cancer Cells. 1990 Mar;2(3):69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch D. H., Lang C., Gillespie D. A. The leucine zipper domain of avian cMyc is required for transformation and autoregulation. Oncogene. 1990 May;5(5):683–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C. V., Dolde C., Gillison M. L., Kato G. J. Discrimination between related DNA sites by a single amino acid residue of Myc-related basic-helix-loop-helix proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Jan 15;89(2):599–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C. V., Lee W. M. Identification of the human c-myc protein nuclear translocation signal. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Oct;8(10):4048–4054. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C. V. c-myc oncoprotein function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991 Dec 10;1072(2-3):103–113. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(91)90009-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R. L., Cheng P. F., Lassar A. B., Weintraub H. The MyoD DNA binding domain contains a recognition code for muscle-specific gene activation. Cell. 1990 Mar 9;60(5):733–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90088-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePinho R. A., Schreiber-Agus N., Alt F. W. myc family oncogenes in the development of normal and neoplastic cells. Adv Cancer Res. 1991;57:1–46. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60994-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enrietto P. J. A small deletion in the carboxy terminus of the viral myc gene renders the virus MC29 partially transformation defective in avian fibroblasts. Virology. 1989 Feb;168(2):256–266. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan G. I., Wyllie A. H., Gilbert C. S., Littlewood T. D., Land H., Brooks M., Waters C. M., Penn L. Z., Hancock D. C. Induction of apoptosis in fibroblasts by c-myc protein. Cell. 1992 Apr 3;69(1):119–128. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90123-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher F., Jayaraman P. S., Goding C. R. C-myc and the yeast transcription factor PHO4 share a common CACGTG-binding motif. Oncogene. 1991 Jul;6(7):1099–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frykberg L., Graf T., Vennström B. The transforming activity of the chicken c-myc gene can be potentiated by mutations. Oncogene. 1987;1(4):415–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M., Knipe D. M. Distal protein sequences can affect the function of a nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Mar;12(3):1330–1339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor P. D., Sawadogo M., Roeder R. G. The adenovirus major late transcription factor USF is a member of the helix-loop-helix group of regulatory proteins and binds to DNA as a dimer. Genes Dev. 1990 Oct;4(10):1730–1740. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann S. R., Abrams H. D., Rohrschneider L. R., Eisenman R. N. Proteins encoded by v-myc and c-myc oncogenes: identification and localization in acute leukemia virus transformants and bursal lymphoma cell lines. Cell. 1983 Oct;34(3):789–798. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann S. R., Eisenman R. N. Proteins encoded by the human c-myc oncogene: differential expression in neoplastic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Nov;4(11):2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.11.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney M. L., Pierce J., Parsons J. T. Site-directed mutagenesis of the gag-myc gene of avian myelocytomatosis virus 29: biological activity and intracellular localization of structurally altered proteins. J Virol. 1986 Oct;60(1):167–176. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.167-176.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato G. J., Barrett J., Villa-Garcia M., Dang C. V. An amino-terminal c-myc domain required for neoplastic transformation activates transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Nov;10(11):5914–5920. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhoff E., Bister K., Klempnauer K. H. Sequence-specific DNA binding by Myc proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 May 15;88(10):4323–4327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzner L., Blackwood E. M., Eisenman R. N. Myc and Max proteins possess distinct transcriptional activities. Nature. 1992 Oct 1;359(6394):426–429. doi: 10.1038/359426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land H., Parada L. F., Weinberg R. A. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature. 1983 Aug 18;304(5927):596–602. doi: 10.1038/304596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landschulz W. H., Johnson P. F., McKnight S. L. The leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science. 1988 Jun 24;240(4860):1759–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.3289117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linial M., Groudine M. Transcription of three c-myc exons is enhanced in chicken bursal lymphoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(1):53–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linial M. Two retroviruses with similar transforming genes exhibit differences in transforming potential. Virology. 1982 Jun;119(2):382–391. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood T. D., Amati B., Land H., Evan G. I. Max and c-Myc/Max DNA-binding activities in cell extracts. Oncogene. 1992 Sep;7(9):1783–1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher B., Eisenman R. N. New light on Myc and Myb. Part I. Myc. Genes Dev. 1990 Dec;4(12A):2025–2035. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma A., Smith R. K., Tesfaye A., Achacoso P., Dildrop R., Rosenberg N., Alt F. W. Mechanism of endogenous myc gene down-regulation in E mu-N-myc tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 1991 Jan;11(1):440–444. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. J., Tjian R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science. 1989 Jul 28;245(4916):371–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2667136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee B., Morgenbesser S. D., DePinho R. A. Myc family oncoproteins function through a common pathway to transform normal cells in culture: cross-interference by Max and trans-acting dominant mutants. Genes Dev. 1992 Aug;6(8):1480–1492. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C., McCaw P. S., Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989 Mar 10;56(5):777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä T. P., Koskinen P. J., Västrik I., Alitalo K. Alternative forms of Max as enhancers or suppressors of Myc-ras cotransformation. Science. 1992 Apr 17;256(5055):373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5055.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn L. J., Brooks M. W., Laufer E. M., Land H. Negative autoregulation of c-myc transcription. EMBO J. 1990 Apr;9(4):1113–1121. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast G. C., Hopewell R., Gorham B. J., Ziff E. B. Biphasic effect of Max on Myc cotransformation activity and dependence on amino- and carboxy-terminal Max functions. Genes Dev. 1992 Dec;6(12A):2429–2439. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast G. C., Lawe D., Ziff E. B. Association of Myn, the murine homolog of max, with c-Myc stimulates methylation-sensitive DNA binding and ras cotransformation. Cell. 1991 May 3;65(3):395–407. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90457-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast G. C., Ziff E. B. Methylation-sensitive sequence-specific DNA binding by the c-Myc basic region. Science. 1991 Jan 11;251(4990):186–189. doi: 10.1126/science.1987636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M., Gann A. A. Activators and targets. Nature. 1990 Jul 26;346(6282):329–331. doi: 10.1038/346329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer C. A., Groudine M. Control of c-myc regulation in normal and neoplastic cells. Adv Cancer Res. 1991;56:1–48. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J., de Lange T., Ramsay G., Jakobovits E., Bishop J. M., Varmus H., Lee W. Definition of regions in human c-myc that are involved in transformation and nuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 May;7(5):1697–1709. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.5.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symonds G., Hartshorn A., Kennewell A., O'Mara M. A., Bruskin A., Bishop J. M. Transformation of murine myelomonocytic cells by myc: point mutations in v-myc contribute synergistically to transforming potential. Oncogene. 1989 Mar;4(3):285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonenko A. T., Linial M. L. gag as well as myc sequences contribute to the transforming phenotype of the avian retrovirus FH3. J Virol. 1992 Feb;66(2):946–955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.946-955.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres R., Schreiber-Agus N., Morgenbesser S. D., DePinho R. A. Myc and Max: a putative transcriptional complex in search of a cellular target. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992 Jun;4(3):468–474. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux D. L., Cory S., Adams J. M. Bcl-2 gene promotes haemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre-B cells. Nature. 1988 Sep 29;335(6189):440–442. doi: 10.1038/335440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. K., Reddy E. P., Duesberg P. H., Papas T. S. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the chicken c-myc gene reveals homologous and unique coding regions by comparison with the transforming gene of avian myelocytomatosis virus MC29, delta gag-myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Apr;80(8):2146–2150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervos A. S., Gyuris J., Brent R. Mxi1, a protein that specifically interacts with Max to bind Myc-Max recognition sites. Cell. 1993 Jan 29;72(2):223–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90662-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]