Abstract

Objective: The Gulf Coast continues to struggle with service need far outpacing available resources. Since 2005, the Regional Coordinating Center for Hurricane Response (RCC) at Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, has supported telehealth solutions designed to meet high service needs (e.g., psychiatry) within primary care and other healthcare organizations. The overall RCC vision is to support autonomous, useful, and sustainable telehealth programs towards mitigating unmet disaster-related needs. Subjects and Methods: To assess Gulf Coast telehealth experiences, we conducted semistructured interviews with both regional key informants and national organizations with Gulf Coast recovery interests. Using qualitative-descriptive analysis, interview transcripts were analyzed to identify shared development themes. Results: Thirty-eight key informants were interviewed, representing a 77.6% participation rate among organizations engaged by the RCC. Seven elements critical to telehealth success were identified: Funding, Regulatory, Workflow, Attitudes, Personnel, Technology, and Evaluation. These key informant accounts reveal shared insights with telehealth regarding successes, challenges, and recommendations. Conclusions: The seven elements critical to telehealth success both confirm and organize development principles from a diverse collective of healthcare stakeholders. The structured nature of these insights suggests a generalizable framework upon which other organizations might develop telehealth strategies toward addressing high service needs with limited resources.

Key Words: disaster medicine, telehealth, telepsychiatry, policy, business administration/economics

Introduction

In 2005, the Gulf Coast experienced unprecedented devastation of infrastructure and resources. The Regional Coordinating Center for Hurricane Response (RCC) at Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, was subsequently established to support Gulf Coast recovery. The RCC seeks to promote telehealth solutions emphasizing post-disaster mental health needs. Telehealth is understood as the utilization of electronic information and technologies towards three principal activities: clinical services, education, and administration.1,2

The RCC's strategic approach is twofold: (1) engage partners as collaborative architects of sustainable telehealth solutions balancing autonomy with efficiency and (2) report on these efforts to advance the understanding of developing telehealth solutions.

A review of telehealth research in the mental health arena reveals several largely descriptive positive efforts.3,4 Other studies report mixed results with limited generalizability.5–9 Still others focused on key development issues, including feasibility, acceptance,10,11 satisfaction,12 cost-effectiveness,13–16 and comparative effectiveness with face-to-face services.12,14,17,18 Available evidence suggests telehealth can generate dependable results, produce good satisfaction, lead to improved clinical status,12,19,20 and offer significant value (e.g., capacity) in the care of injury, disease, and mental illness.21

Despite evidence of effectiveness, telehealth remains largely at the periphery, hampered by an array of challenges22 including inadequate resources,3 provider resistance,3,14,23 workflow integration,3,4,24–26 regulatory and technology issues,3,15,18,20,21,23,26,27 diagnostic fidelity, and confidentiality.20

The experiences of RCC partners constructing post-disaster telehealth solutions offer valuable development insights spanning a range of organizations, intentions, implementations, and outcomes. We sought to document this diverse knowledge base using a qualitative research framework to identify shared challenges, successful tactics, and recommendations for scalable sustainability.

Subjects and Methods

Data were collected from key informants across Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana and with national organizations with Gulf Coast recovery interests. Eligible informants represented all organizations engaged by the RCC regardless of whether collaboration resulted. Participating informants were categorized by their roles (i.e., administrative, advocacy, clinical, or technological). Semistructured interviews were conducted through videoconferencing or telephony if videoconferencing was unavailable. Open-ended questions queried personal and organizational experiences with telehealth across all stages of consideration, implementation, utilization, and maturation. Follow-up probes elicited detailed information on organizational structure, finances, technology, policies, protocols, perceptions, barriers, benefits, and outcomes.

Data Collection

Forty-nine potential informants were invited to participate. Written consent was obtained prior to interview. Interviews averaged 1 h for informants actively engaged in telehealth and 30 min for those not engaged. Two facilitators conducted each interview and reviewed interview transcripts for completeness and accuracy.

Data Analysis

The research design was qualitative-descriptive.28,29 Interview transcripts formed the dataset. Structural coding methodology was used with Atlas.ti6© (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software DevelopmentGmbH, Berlin, Germany) qualitative analysis software30 to label and index data related to each interview question.31 Following collaborative agreement on code relevance, eight study analysts generated a master list of codes and subcodes highlighting relevant telehealth themes.

Three analysts individually coded each transcript by interview question and master code list. Independently coded transcripts were merged and collaboratively reviewed to verify consistency and resolve discrepancies. This produced “consensus-coded” transcripts for formal query. Analysts reviewed queries and identified relevant themes as the basis for the study's report. Twelve informants willing to review and validate conclusions formulated comments on the report.29

Results

Key informants represented 23 of the 24 organizations approached by the RCC (95.8%). Thirty-eight informants participated (77.6%), including 17 administrative, 8 clinical, 9 technical, and 4 advocacy stakeholders. One administrative informant's interview rendered no relevant telehealth information and was excluded. More than half of the respondents (n=22, 58%) represented organizations in Louisiana, seven respondents (18%) represented organizations in Mississippi, and three (8%) represented ones in Alabama. Four respondents represented advocacy organizations at the national (n=3) or regional (n=1) level, and two respondents were located in Georgia and Oregon, respectively.

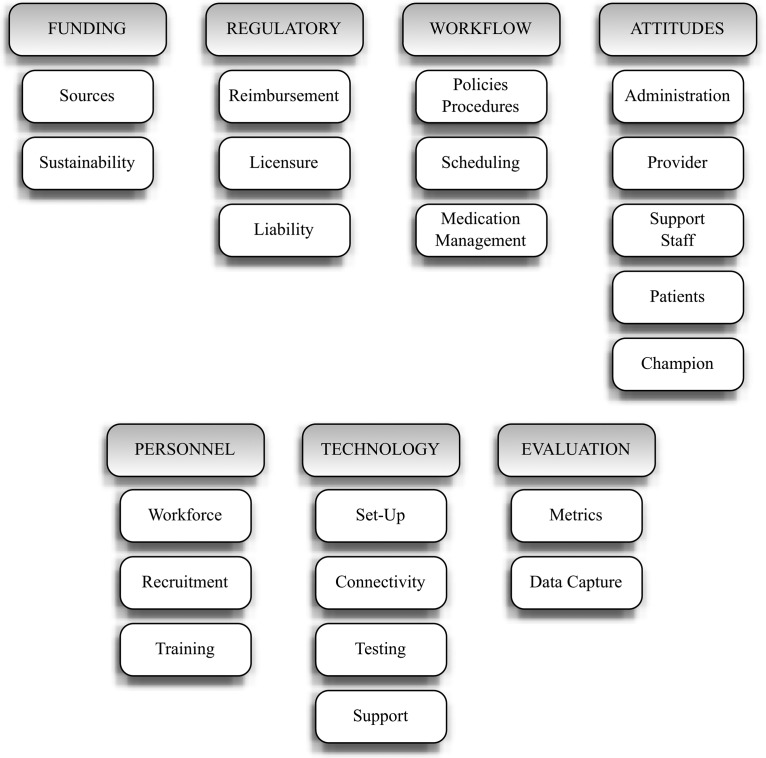

Seven key elements critical to telehealth success were identified from informants' accounts (Fig. 1). Table 1 summarizes relevant informant experiences and recommendations, and Table 2 highlights representative quotes clarifying each key element.

Fig. 1.

Key elements in telehealth development.

Table 1.

Key Informant Experiences with Telehealth Development

| KEY ELEMENTS | RELEVANT KEY INFORMANT EXPERIENCES | COMMENTS/SOLUTIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Funding | ||

| Sources | • Grants (federal, state, nonprofit) • Donations (usually for equipment only) • Grants/donations inadequate to support full cost of implementation |

• Operating budget (ideally, organizations will be able to work funding into annual operating budgets) • As technology changes, organizations will need additional funding to make capital investments and replace outdated technology. • Service-oriented organizations may not have personnel to pursue funding. Funding agencies should aggressively disseminate information on offerings. |

| Sustainability | Common concerns: • Will the program be self-sustainable? • How will you account for an increase in demand for services? • What if grants dry up because of economic policy, political changes, etc.? |

• Larger grants should be offered initially to establish more services at start-up, providing greater scale for services and reduced costs in the long run. • Need to define clear reimbursement streams that make program self-sustainable. |

| Regulatory | ||

| Reimbursementa | • Struggle to find out insurance rules for TH reimbursement • Private insurers continue to avoid TH reimbursement. • Problems with reimbursement across state lines • Problems with reimbursement to multiple providers (based at local and distant sites) |

• Reimbursement issues preclude the expansion of TH programs and create resistance to its development. • National TH reimbursement mandate is needed. • Use teleradiology as a model to establish reimbursement rules. • Provide TH services under a contract rather than individual fee-for-services. |

| Licensure | • Out-of-state provider had to hold a license to practice medicine in the state where patient resided. • Ad hoc efforts had to be made to work with nursing and physician licensing bodies at the local site. |

• Providers need to maintain active licenses in various states (less than satisfactory solution). • National TH license suggested, at the very least in the case of disaster |

| Liability | • Whose malpractice insurance is responsible? | • Specific liability policy adjustments may be necessary. |

| Workflow | ||

| Policies and procedures | • Perceived paucity of structured guidance • Workflow protocols had to be made from scratch. • Protected medical information had to be transferred using fax or Internet. • Best physical space for TH practice decided by trial and error • Additional time needed to familiarize patient with TH set-up and function |

• Consider necessary workflow changes prior to implementation. • Be flexible and willing to tweak procedures as the program launches. • Train staff on new protocols and keep up to date on changes. • EMR capacity for electronic storing and sharing of protected medical information critical to facilitate TH. • A widely accepted user manual containing recommended procedures, protocols, sample forms, and templates for consent forms and collaborative agreements is needed. |

| Scheduling | • Major issue is coordinating schedules between local and distant sites. • Reduced ability to “work patients in” • “No shows” result in waste of critical time at local and distant sites. |

• Assign responsibility for scheduling to a single office or person who handles scheduling at both ends. • Electronic scheduling systems connected to EMR may be useful. • Consider integration of TH into regular clinical workflow instead of setting aside large chunks of time for face-to-face services and other chunks of time for TH services. • Build in extra time around appointments for technological glitches (especially in the beginning). |

| Medication management | • Need for handwritten prescriptions for controlled substances is a problem because provider is at remote location. | • Prescriptions are mailed overnight to local site. |

| Attitudes | ||

| Administratora | • Support of organization administrators impacts all aspects of program implementation from setting aside adequate facility space to staffing support. | • Administrator buy-in is critical to successful implementation and sustainability of TH programs. |

| Providera | • Attaining provider buy-in to the TH model is the single most important challenge to TH implementation. | • Clarify the role of TH as adjunctive rather than replacing traditional models of care. • Involve providers early in the development of TH initiatives. |

| Support staffa | • Nurse support can make or break a TH program. | • Involve nursing staff in decision-making process from the beginning. |

| Patient | • Children in particular are actually enthralled by the technology involved with TH. | • Need to convince patients of the quality of TH with respect to traditional modes of mental healthcare. • After a successful TH interaction, patient acceptability is almost universal. |

| Championa | • TH promoters help expedite services that need to happen in order for systems to function. • Consider where a champion may be necessary: “hub” and “spoke” ends; IT department; specialty care; board of directors; etc. |

• Champions are utterly essential to TH program sustainability and expansion. |

| Personnel | ||

| Workforce | • Staffing shortage, employee workloads (having to assume TH duties on top of regular duties), or both make TH implementation very difficult. | • Personnel day-to-day responsibilities take priority, and TH initiatives fall to the bottom of the list. |

| Recruitment | • Shortage of specialty or subspecialty providers is a widespread challenge, irrespective of TH. • Lack of uniform reimbursement policies discourages providers from embracing TH. |

• TH itself may be a way to circumvent shortage of specialist care. • Recruit younger providers who may not be as averse to new technologies. • Templates for contracts clarifying legal, financial, and clinical responsibilities would be useful to simplify recruitment. |

| Training | • Need to train providers and support staff in the use of TH equipment. | • Seek out training support instead of reinventing the wheel. • Use videoconferencing to pipe in training sessions. • Pursue vendor support for training. |

| Technology | ||

| Set-up | • Many times donated equipment sat idle because of lack of IT support for set-up. • Inadequate wiring infrastructure at deployment sites can be a problem. |

• Involve vendors in set-up • Consider back-up/redundancy of software and electronic media. • Ensure adequate space is provided to house equipment (quiet, secure locations; equipment is safe from flooding or other hazards, or at least portable in the case of disaster). |

| Connectivitya | • Bandwidth and other connectivity issues were pervasive. • Firewalls needed to secure network integrity represented both a technological challenge to IT-naive local organizations and a barrier to connectivity with computer systems at partner organizations. |

• Pursue funding to attain appropriate bandwidth connectivity. • Understand that mobile units may not be the best solution because of connectivity issues. |

| Testinga | • Equipment did not function as expected, and reliability of transmissions was low. | • Test equipment thoroughly, even before introducing to providers. |

| Supporta | • Smaller clinics do not have in-house IT teams. • Even when IT teams available, level of expertise to operate TH equipment may be low. • Frustration with simple technology issues discourages adoption of TH solutions. |

• Technical support needs to be available on the spot, especially at the beginning of TH operations. • Ensure access to technological support, preferably in-house. • Try to keep facility and equipment up to date with technological developments (this will require funding allocation). |

| Evaluation | ||

| Metrics | • Metrics to consider: patient and provider satisfaction, change in patient outcomes and diagnoses, cost, personnel workload and time invested, etc. | • Do not wait until the program is underway to define what metrics to collect for desired level of program evaluation. |

| Data capture | • Consider building in metric collection and/or prompts to the EMR. • Surveys (paper or electronic) • Focus groups with staff |

• Evaluation of TH programs should be applied as an integral part of initial and ongoing program design, implementation, and practice. |

Signals a critical component.

EMR, electronic medical record; IT, information technology; TH, telehealth.

Table 2.

Key Elements and Representative Quotes

| ELEMENT | QUOTE |

|---|---|

| Funding | |

| “… at the end of the day the funding ends. To me any real successful project should be sustainable well beyond initial funding and I see more projects stopping the time the funding ends than projects continuing at the time the funding ends. We are still really far from it.” (RCC 7-2:40) | |

| “Once some of those resources started to pull back, which was about a year into our telehealth program, then we started to experience, ‘Oh, God, they don't have a ride. Maybe we need to get bus tokens.’ Because when the money went, then some of those resources that helped it go real smooth for us were gone. So, we had some challenges with our clients that we forgot were there once the resources left” (RCC 5-3:172) | |

| Start-up: “Right now the cost to do it, to acquire the technology and the operations cost, is prohibitive…in the places we work at” (USA 5-4:172) | |

| Capital: “But I think another barrier is some community health centers are thinking even though they receive free equipment; they might associate making that equipment work properly with, ‘Okay, I have to spend some additional dollars that I don't necessarily have. Where am I going to get that money from to do this?’” (USA 6-1: 149) | |

| “And of course there is obsolescence built into technology. We just got through talking about having a fiber optic line; we just got through talking about resolution on the screen and the different kinds of screens. So every 5 years you probably will have another capital outlay to keep up with the progress of things…” (USA 7-1:166) | |

| Regulatory | |

| “The greatest challenge is, ‘Okay if I get into this and I provide the service, how do I get paid?’” (RCC 6-9:29) | |

| “For clinical services, we had trouble getting the doctors to buy into the clinical part of it. They believe in it but there is always a reimbursement issue that puts the brakes on the clinical side of it.” (RCC 7-3:60) | |

| Reimbursement: “Who gets paid and how much and for what? The specialist and everybody want to get paid so you have to figure out how to split the fees.” (RCC 6-4:35) | |

| “We don't really know what the cost structure is with all of this. Do I compensate a subspecialist in New York at the New York rate, or do I compensate that specialist at the Biloxi rate?” (USA 5-4:15) | |

| Licensure: “ there ought to be a process beyond a governor waiving the requirements…The governors agreeing to have a process…that would be the first to come to your aid, a process for telemedicine licensure that's renewable every 2–4 years, and across all specialties that are applicable to the use of telemedicine. I am also for a national MD license that would include the use of telemedicine in disaster areas.” (USA 7-1:43) | |

| Liability: “Luckily for the state of Mississippi, we are capped on medical malpractice. Some of the other states that we are looking at going to don't have that regulatory cap. Alabama for instance…” (RCC 6-3:52) | |

| “We had to also clear this with our malpractice coverage group, who had to make a decision about whether they would cover us and our telehealth services. (RCC 6-6:14) | |

| Workflow | |

| Internal policy: “We will start a process and then we say, ‘Well, what are you going to do?’ ‘Well, I can't do this, I don't have permission to do this,’ and that has been a big barrier as well, as this is new frontier for many of us. And we are just creating policy as we go.” (USA 6-1:73) | |

| Collaborations: “… waiting to figure out what all these other collaborative relationships are going to be” (USA 6-5:122) and “… trying to figure out what kind of memorandum of understanding or contracts we would have with the subspecialists to provide that service, we haven't even gotten to that point yet” (USA 6-5:124) | |

| Procedures: “And so we have insisted that [telehealth encounters] take place concurrently in clinical settings, so that I've got a backup doctor, a backup system on the other end with the patient. I insist on two things, that there be a phone available should my visual transmission cut out due to a thunderstorm…that has happened, and I am in the middle of a critical moment with my patient, I can pick up the phone and I can carry on that conversation” (USA 7-1:202) | |

| Scheduling: “It is just logistics. Making arrangements, the timing, the coordinating of the schedules with the patients, with the specialist and putting it all together.” (RCC 6-4:160) | |

| “… we have to have a really clear scheduling process…with technology. 10:01, 10:02, it matters. So, we have to have a clear scheduling process just as we do with any clinical activity.” (USA 5-4:112) | |

| “We had an issue with controlled medications…the fact that you need to have a handwritten prescription. So that means [sending prescriptions] by overnight service.” (RCC 6-1:52) | |

| Attitudes | |

| Administrator: “…getting some of the leadership to see the importance of using it. I'm not saying they don't think it's important, but it may not be at the top of their priority list.” (RCC 7-6:33) | |

| Provider: “Many people are frustrated when they can't get a signal or…not having enough bandwidth on the servers, if there is too much…interference or breakup that significantly limits people's willingness to use it for clinical purposes.” (RCC 6-8:21) | |

| Nurse: “The nursing staff at the hospitals can actually be a major player in deciding if the system is going to work or not. If they were not involved in the decision process and they weren't involved initially looking at the program to make sure they were comfortable with it, that can easily undermine the program.” (RCC 6-3:56, 57) | |

| Champion: “The biggest challenge is first finding a champion…at the spoke end, [who] really understands and believes in [telehealth] and then finding a champion at the subspecialty end where that individual believes in its effectiveness and is willing to try [telehealth] as a different model of care.” (RCC 6-2:22) | |

| Patient: “… we found out that what we were describing wasn't sufficient for the consumer to be comfortable, so we elaborated a little bit more, and we were a little bit more patient in the explaining of [telehealth] to the consumer, because they were coming in to receive some type of psychiatric treatment, and if [getting acquainted with the technology] took longer than 5 minutes,…we gave them as much time as they needed before they got comfortable.” (USA 6-7:191) | |

| Personnel | |

| “So [telehealth] kept falling to the bottom of our list, honestly. We were trying to take care of what was coming in our doors every day. We were never able to get caught up to think about [telehealth]” (USA 5-5:73) | |

| Staffing: “If we had a staff person who, for a few months that's all he or she was thinking about, was getting [telehealth] going, it would have gotten done.” (USA 5:5:133) | |

| “There are not enough providers who see [telehealth] as a way of providing care” (RCC 7-5:38) | |

| Nurses: “Now one of the glitches is, you've got to be sure you have, at a minimum, an LPN or an RN at the other sites to get the vital signs, the BMI, and all these other [clinical] issues” (USA 6-3:55) | |

| “There is also a nurse practitioner who facilitates the patient's connection to the mental health professional. They also need to be able to write prescriptions and coordinate medications or follow-up visits with the patient at the end of the session” (RCC 6-7:66) | |

| Training: “The cost for set-up and training [is borne] at the initial onset. So that first year or at least 6 months, you need people well trained in [telehealth].” (RCC 6-2:207) | |

| “…the turnover in personnel, where the patient is. So there is always an educational process, re-educational process. You train and you train and then a new person shows up so you are right back to training again. You give them material, there is always the time factor, ‘I don't have time to do it,’ ‘I don't have time to read it’” (RCC 7-3:164) | |

| Technology | |

| “… one of my complaints is that for a while…the equipment sat in its box in the foyer of the agency…because nobody really knew exactly what to do with it. So yes, some training would have been helpful” (RCC 6-10:56) | |

| “… the level of technical assistance that was being offered was really limited…there really needed to be a much more concerted, consistent, and persistent on the ground presence here in New Orleans…and I don't think that periodic drop-bys every 6 months or a year was sufficient to make that work” (USA 7-3:73) | |

| “Number 1 would be technical assistance. I had been on the phone for several days with an engineer who was supposed to be in charge of it, but he point blank told me he wasn't very familiar with it. And we went back and forth with it for a couple of days and things just kind of fell apart, so technical assistance is paramount” (USA 6-8) | |

| “… you've got some very upset and stressed person, and you are in a difficult environment, even if it's a normal fixed clinic, and you need help. Well, the truth of the matter is you need someone who is sophisticated and who technologically deals with this. Well, where are you going to get that person…for $80,000 a year or $60,000 a year, to sit down for the brief telehealth encounters you have in any given day?” (USA 5-4:80) | |

| “… when we do have a technical problem, we like to analyze it, why it happened, what created the problem, was it a failure in procedure, was it a failure in communication, and [we] try to build some kind of redundancy into the system where that failure won't happen again” (USA 6-7:139) | |

| Evaluation | |

| “I think at the end of the day, we have to first decide what success is…. Is success a patient getting better? Is success some sort of cost-effectiveness? Is success some kind of client or patient/provider uptake? I think those are all types of success.” (USA 5-4: 83) | |

| “I think that success is a measure. The measurement we use of course is one of patient satisfaction.” (RCC 7-5: 27) and “… the other success factor is that we…continue to keep a full schedule.” (RCC 7-5: 28) | |

| “… if there is a specific client that the technology is used with, and then other clients that the technology is not used with, maybe marking the progress of those clients and comparing the level of feedback and the level of growth and movement of the clients….” (RCC 6-10: 28) | |

Attribution of quotes is given by (transcript number paragraph: line).

BMI, body mass index; RCC, Regional Coordinating Center for Hurricane Response, USA, University of South Alabama.

Funding

Inadequate funding was reported to impact both engagement and implementation (Table 1). Most programs received external funding to acquire videoconferencing equipment. Funding, however, was often inadequate to cover the full cost of implementation, secure technical support, and cover staffing requirements. Informants also reported unanticipated expenses following implementation (e.g., client transportation needs). The most vulnerable telehealth initiatives were completely reliant on external funding. Well-defined funding commitments were evident where telehealth was an integral part of the organization's strategic model.

Regulatory

Informants consistently identified three regulatory challenges: reimbursement, licensure, and liability (Table 1).

Reimbursement is a longstanding challenge impacting telehealth viability, particularly for organizations serving the uninsured. Providers reported difficulty receiving telehealth reimbursement (regardless of payer), variability of reimbursement across states, billing complications at both ends of the encounter (due to limits on co-pay splitting), and complications with reimbursement for specialists and sub-specialists.

Provider licensing and credentialing were pervasive impediments to telehealth implementation. Ensuring that providers are authorized at both the provider and patient sites can be burdensome. To ease this burden, informants recommended a national telehealth licensure mandate, including expedited disaster protocols specifying longer authorization terms given the longitudinal efficiencies of telehealth presence. Absent telehealth licensure provisions, providers must maintain licenses in states where both the providers and patients are located. Informants also highlighted the importance of appropriate nursing credentialing for personnel who facilitate the telehealth encounter with prescriptions, medication coordination, and follow-up scheduling.

Liability concerns were not widely reported and depended on the nature of the program and state-specific liability caps. Some program directors expressed interest in better guidance on telehealth service coverage. Reported measures taken to ensure coverage included seeking attorney advice on policy adjustments.

Workflow

Three critical workflow elements were identified: policies and procedures, scheduling, and medication management (Table 1).

Informants discussed the lack of guidance related to established telehealth policies and procedures resulting in the novel development of manuals for many organizations. Other workflow challenges included (1) coordinating telehealth policies and procedures across organizations, particularly with screening, scheduling, managing medications, and co-managing patients, and (2) identifying skilled professionals responsible for maintaining confidentiality, facilitating encounters, and responding to emergencies, whether clinical or technologic.

Storing and sharing clinical records including personal health information were considered a challenge. Electronic health record solutions, ideally with multimedia capabilities, were deemed essential to telehealth success. Absent an electronic health record, documentation was faxed to remote sites despite recognition of potential personal health information security risks.

Scheduling was one of the greatest procedural challenges identified. Clear communication protocols between sites were deemed critical. Patient “no shows” had a deleterious impact at both ends of the telehealth encounter. Managing these missed appointments was particularly difficult when the only service option was via telehealth. Strategies used to ensure appointment compliance included phone reminders, letters, and other assistance (e.g., childcare, transportation).

Managing medications was also challenging where on-site providers were not authorized to write controlled substance prescriptions. Telehealth providers reportedly used overnight delivery of hand-written prescriptions when necessary.

Attitudes

Attitudes toward telehealth implementation were a consistently reported theme, particularly provider resistance and stakeholder buy-in. Informants identified several contributors to provider resistance, including limited understanding, negative preconceptions, dislike of technology, misaligned expectations, limited training opportunities, preference for traditional encounters, complacency, fear of revenue loss, and fear of being watched or recorded. Strategies suggested for addressing provider resistance included exposure to successful telehealth programs and early provider inclusion in the development process.

Stakeholder buy-in was considered crucial to telehealth success. Administrator buy-in was recognized as broadly impacting telehealth implementation, including adequate physical space, funding support, and staff assignment. Other essential stakeholders included nursing, information technology (IT), and administrative staff. The importance of patient and family acceptance was also noted given patient reports of disliking the technology and concern about equivalence with traditional services. Provider “champions” were repeatedly mentioned as essential to telehealth development as they are noted to attract others to support programmatic success.

Personnel

Gulf Coast workforce issues presented a formidable post-disaster challenge to telehealth development. Informants reported having no personnel capacity to dedicate to telehealth implementation. They described personnel working well above capacity to maintain routine operations, leaving little time for telehealth development. Recruiting certain specialists (e.g., psychiatry) was a noted challenge due to both limited acceptance of telehealth and global supply shortages. Recruiting was complicated by the need to clarify legal, financial, and clinical considerations. Training of personnel on the use of telehealth equipment was challenging because of limited time, funds, and resources. Frequent personnel turnover also created the need for perpetual training, which threatened program maturation.

Technology

Technology challenges were frequently identified (Table 1). Informants indicated that lack of IT support delayed or discouraged telehealth implementation. Smaller clinics do not typically employ IT specialists, presenting both implementation and maintenance difficulties. In some small communities, it was difficult even to find IT specialists. Organizations with IT specialists sometimes fared no better because of lack of videoconferencing expertise and limited vendor support.

Connectivity issues were pervasive. Lack of adequate bandwidth and funding to increase it was reported, predominantly in rural communities. Informants acknowledged that current federal, state, and private initiatives expanding broadband coverage would eventually resolve this challenge. Some organizations implemented satellite connectivity solutions, but transmission quality was found to be inadequate and costly. Another noted challenge was network architecture. Closed networks, firewalls, and equipment incompatibility hampered successful connections. Poor transmission quality was broadly deemed detrimental to telehealth success.

Equipment not performing as expected was another reported challenge. Moreover, limited time and resources to resolve equipment challenges only compounded the issue and ultimately discouraged telehealth use. Informants recommended strong vendor support and thorough equipment testing to minimize operational difficulties that jeopardize telehealth adoption. The issue of catastrophic equipment failure led some informants to recommend back-up equipment and emergency protocols to avoid service interruption and dissatisfaction. Attendant capital costs for back-up equipment, however, further stress a financially vulnerable telehealth model.

Evaluation

Participating key informants occupied different developmental stages from consideration and implementation to utilization and maturation. Evaluation practices, therefore, varied from nonexistent to comprehensive. When asked about telehealth evaluation, informants largely focused on clinical benefits and administrative implications. Commonly reported telehealth metrics for clinical assessment included (1) provider and patient satisfaction, (2) workflow output, and (3) patient outcomes. Administrative metrics included quantification of the efficiency and capacity of telehealth operations, as well as cost analysis (direct, indirect, capital, and operational costs). The electronic health record was widely noted as key to collecting necessary evaluation data.

Discussion

The RCC's initial focus sought to address unmet mental health service demand by developing autonomous, useful, and sustainable telehealth solutions. The resulting collaborations emerged in multiple environments with varied program objectives, which reflected specific organizational priorities (e.g., from primary care to human immunodeficiency virus education). Within this heterogeneous context, our informant reports take on additional significance by building upon existing knowledge found largely in single-program implementations within telehealth.

Seeking to advance our collective understanding of telehealth across all RCC collaborations, however, led to our study's methodological approach. Our study presents firsthand reports of post-disaster telehealth development experiences across three states from a diverse group of organizations. Our qualitative research approach distills disparate experiences into a common knowledge base useful in program strategy development, but also essential in establishing a dimension of “familiarity” necessary for telehealth to move into the mainstream.23

The seven key elements identified can be found among previous studies, but often independently with support from single programmatic efforts.3,4,32,33 The developmental guidance offered in this analysis possesses broader applicability for a variety of organizations that are considering telehealth given similar challenges of unmet need with limited resources.

Among the key elements identified, funding is both a catalyst and a fuel fundamental to telehealth success. Informant experiences underscore that funding considerations require organizational commitments, including support for IT.3 It is further recognized that cost-effectiveness can only emerge once telehealth activity scales beyond part-time single-solution applications. Scaling strategies range from maturing all three Health Resources and Services Administration–defined activities to shared resource utilization across multiple specialties and organizations.34

Informant responses emphasize that sustainability hinges on revenue generation. Currently, Medicaid telehealth reimbursement rules vary across states. At least 27 states report some degree of telehealth reimbursement.35 Medicare restricts which settings qualify as originating sites and pays for a limited number of telehealth services. Clinical psychologists and social workers, however, cannot currently bill for telehealth psychotherapy under Medicare.36 Private payers generally do not universally reimburse for telehealth services, although some are beginning to follow public payers with selected services. Telehealth reimbursement rules are predicted to eventually match traditional payment mechanisms but will require additional evidence supporting telehealth effectiveness.37

Informants confirmed the pervasive licensure challenge noted in the literature when seeking specialists beyond state borders.15,21,23,38,39 Currently, 27 states and the District of Columbia have taken no explicit action regarding interstate telehealth licensure. These states rely upon broad “practice of medicine” statutory clauses and require unrestricted licensure if the therapeutic relationship involves the state in question. Although not explicit, these clauses could be construed to consider telehealth care as falling within the practice of medicine.40 The Health Care Safety Net Act of 2002 authorized incentive grants for state licensing boards to assess interstate cooperation and promote policy initiatives to reduce telehealth barriers.41 The Federation of State Medical Boards also supports a special-purpose license to cover telehealth encounters nationally. To date, only 10 states have adopted some version of this model, and state portability remains an ongoing advocacy issue.42 In contrast, the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) proactively supports telenursing.43 The NLC permits interstate practice for nurses licensed in their home NLC state, provided the nurse acknowledges being subject to each state's regulations. At present, 23 states have joined the NLC.44 The Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Compact45,46 developed in 2002 is similar to the NLC and promises further promotion of advanced telenursing practice once implemented.

Informant liability concerns were notably less prominent. Telehealth malpractice policy modifications continue to be specialty dependent and made on a case-by-case basis.34 Provider liability concerns may also contribute to limited adoption rates found among RCC collaborators.13

With regard to telehealth workflow, informants repeatedly echoed the importance of clear policies and procedures.3,4,20 The expressed need for telehealth manuals including templates has been previously recognized.47,48 The rapidly evolving nature of telehealth creates new challenges and opportunities in developing, distributing, and updating such resources.

As previously reported,3,4,20 informants confirmed that buy-in at all levels, including patients, is key to telehealth development success. Integration of telehealth into routine operations is noted to be no different than incorporating any new organizational procedure.49,50 As such, there is notable value in utilizing “champions” throughout the developmental process.51 Sustained acceptance of telehealth is also supported by incorporating formal telehealth skills training to providers and support personnel alike.52,53

Our study and others underscore the need to appropriately staff telehealth operations with dedicated and adequately trained personnel, including effective IT support.3,20,26 Attempting to implement without these provisions risks programmatic failure. Strategies for organizations lacking IT resources might include partnerships with larger institutions employing IT specialists or cost-sharing among organizations.54

Another technological need identified involves system interoperability.3,21,39 The 2009 HITECH Act55 addresses this challenge with an unprecedented investment supporting the deployment of critical technologies (e.g., electronic health record) necessary for telehealth maturation. Also of note is H.R. 2068, the Medicare Telehealth Enhancement Act of 2009, introduced by Congress “to improve the provision of telehealth services under the Medicare Program, to provide grants for the development of telehealth networks, and for other purposes.”56 This bill highlights governmental interest in telehealth service expansion, telehealth provider credentialing, and provisions for home-based telehealth access. Overall, legislative attention appears to be growing toward realizing the promise of telehealth solutions.

Consideration of this study's results should be balanced against several limitations. First, eligible study informants represent a convenience sample of only organizations approached by the RCC. We did not identify other organizations independently pursuing telehealth following the 2005 hurricanes. Second, sample weighting plays out in several ways. Informant geographic distribution reveals a preponderance of Louisiana-based organizations attributed, in part, to the RCC having more familiarity with the Louisiana healthcare landscape. Furthermore, the RCC strategy of approaching only those organizations with strong interest in telehealth resulted in sample weighting toward organizations that ultimately engaged in telehealth. In addition, the variability in the number of informants by organization was related to program maturity and resulted in sample weighting toward mature organizations. Lastly, study results may not generalize beyond post-disaster circustances within the southeastern United States. Although we believe the reported insights hold broader value for vulnerable populations with unmet service needs, it remains possible that the telehealth experiences reported herein may be influenced by variables unique to a post-disaster Gulf Coast.

Conclusions

The Gulf Coast, overwhelmed by disaster, exposed an untenable situation of need far outpacing resources. In response, the RCC seized an opportunity to support telehealth adoption in order to maximize the utility of scarce mental health resources. Within these efforts, a wealth of data pertaining to telehealth development was captured, demonstrating that as telehealth redefines the provider–patient relationship, so must it redefine stakeholder roles, environments, and protocols.57,58

But more than redefinition, widespread adoption requires cultivating the familiarity with telehealth revealed within our informants' reports.22,59 We believe that the insights provided by key informants, structured as key elements, might strategically assist other organizations to benefit from rather than repeat lessons learned in early telehealth development. These key elements are offered as a developmental framework to guide implementation efforts.60

Technology has transformed the way we interact with each other. And though it may seem to have happened overnight, widespread acceptance and usage remain elusive and require recruiting those comfortable with the past—into the future. A far-reaching telehealth adoption strategy will require more than overcoming specific barriers. It will take time, persistence, and vision to move from replicating historic efforts to building upon them.

Acknowledgments

This qualitative study was supported by funds from the Regional Coordinating Center for Hurricane Response at Morehouse School of Medicine under the Office of Minority Health, Department of Health and Human Services (CFDA number 93.004) and grant number MPCMP061011-01-07. Key informants from the following sites permitted us to analyze their interview responses: All Healers Mental Health Alliance; Alta Pointe Health Systems; Children's Health Fund; Coastal Family Health Center; Counseling Solutions; Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals; EXCELth, Inc.; Louisiana Primary Care Association; Louisiana Public Health Institute; Louisiana State University TeleMed; Mercy Family Center; Mississippi Primary Care Association; Morehouse School of Medicine; New Orleans Health Department; Rapid Evaluation and Action for Community Health in New Orleans, Louisiana; Southern University and A&M College; St. Anna's Episcopal Church; Trinity Counseling and Training Center; Tulane Community Health Center at Covenant House; University of Mississippi Medical Center; and University of South Alabama. Yolanda Dunbar-Johnson, LCSW-BACS, MS, Heidi Sinclair, MD, MPH, Douglas Walker, PhD, and Jeb Weisman, PhD, provided thoughtful comments on drafts of this manuscript. Crystal A. Kinnard, MEd, provided administrative support.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. T.J.K. and M.I.A. are responsible for study concept and design and for study supervision. S.L.E., M.S., A.H.N., and K.M.B. are responsible for data acquisition. M.I.A., S.L.E., M.S., M.L.I., A.H.N., K.M.B., and R.D.F. are responsible for data analysis and interpretation. T.J.K., M.I.A., R.D.F., S.L.E., and M.L.I. are responsible for manuscript drafting. T.J.K., M.I.A., S.L.E., M.L.I., M.S., A.H.N., K.M.B., R.D.F., and A.V.B. are responsible for manuscript revision for important intellectual content. T.J.K., M.I.A., S.L.E., M.S., M.L.I., A.H.N., K.M.B., and R.D.F. are responsible for qualitative analysis. M.I.A., S.L.E., M.L.I., M.S., A.H.N., K.M.B., and R.D.F. are responsible for administrative, technical, and material support.

References

- 1.Sima C. Raman R. Reddy R, et al. Vital signs services for secure telemedicine applications. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:361–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Resources and Services Administration. Telehealth. www.hrsa.gov/telehealth/ [Dec 11;2011 ]. www.hrsa.gov/telehealth/

- 3.Alverson DC. Shannon S. Sullivan E, et al. Telehealth in the trenches: Reporting back from the frontlines in rural America. Telemed J E Health. 2004;10(Suppl 2):S-95–S-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moehr JR. Schaafsma J. Anglin C, et al. Success factors for telehealth—A case study. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75:755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaren PM. Laws VJ. Ferreira AC, et al. Telepsychiatry: Outpatient psychiatry by videolink. J Telemed Telecare. 1996;2:59–62. doi: 10.1258/1357633961929303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohland BM. Saleh S S. Rohrer JE. Romitti PA. Acceptability of telepsychiatry to a rural population. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:672–674. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hersh WR. Hickam DH. Severance SM, et al. Diagnosis, access and outcomes: Update of a systematic review of telemedicine services. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(Suppl 2):S3–S31. doi: 10.1258/135763306778393117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickelson DW. Behavioral telehealth: Emerging practice, reserach and policy opportunities. Behav Sci Law. 1996;14:443–457. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh G. O'Donoghue J. Soon CK. Telemedicine: Issues and implications. BMJ. 2002;324:1434–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grugaugh AL. Cain GD. Elhai JD, et al. Attitudes toward medical and mental health care delivered via telehealth applications among rural and urban primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:166–170. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318162aa2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monnier J. Knapp R. Frueh BC. Recent advances in telepsychiatry: An updated review. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1604–1609. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.12.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinzelmann PJ. Williams CM. Lugn NE. Kvedar JC. Clinical outcomes associated with telemedicine/telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2005;11:329–347. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2005.11.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cusack CM. The value proposition in the widespread use of telehealth. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:167–168. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2007.007043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinowitz T. Brennan DM. Chumbler NR, et al. New directions for telemental health research. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:972–976. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schopp LH. Demiris G. Glueckauf RL. Rural backwaters or front-runners? Rural telehealth in the vanguard of psychology practice. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2006;37:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shore JH. Brooks E. Savin DM, et al. An economic evaluation of telehealth data collection with rural populations. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:830–835. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuevas CDL. Arredondo C. Cabrera M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telepsychiatry through videoconference versus face-to-face conventional psychiatric treatment. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12:341–350. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Germain V. Marchand A. Bouchard S, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy administered by videoconference for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:42–53. doi: 10.1080/16506070802473494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schopp L. Johnstone B. Merrell D. Telehealth and neuropsychological assessment: New opportunities for psychologists. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2000;31:179–183. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarvis-Selinger S. Chan E. Payne R, et al. Clinical telehealth across the disciplines: Lessons learned. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:720–725. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmons S. Alverson D. Poropatich R, et al. Applying telehealth in natural and anthropogenic disasters. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:968–971. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puskin DS. Foreword. In: Tracy J, editor. Telemedicine technical assistance documents. Columbia, MS: University of Missouri School of Medicine; 2004. p. iii. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmeida M. McNeal R. Mossberger K. Policy determinants affect telehealth implementation. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13:100–107. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman DR. Pevzner J. Rodriguez M, et al. Understanding workflow in telehealth video visits: Observations from the IDEATel Project. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Speedie SM. Ferguson AS. Sanders J. Doarn CR. Telehealth: The promise of new care delivery models. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:964–967. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puskin DS. Cohen Z. Ferguson S, et al. Implementation and evaluation of telehealth tools and technologies. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:96–102. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman S. The use of telemedicine in psychiatry. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2006;13:771–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grbich C. Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Ltd.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design; Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Ltd.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheeler T. Thoughts from tele-mental health practitioners. Telemed Today. 1998;6:38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Washington, DC: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kangarloo H, et al. Process models for telehealth: An industrial approach to quality management of distant medical practice. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999:545–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinstein RS, et al. Integrating telemedicine and telehealth: Putting it all together. Curr Principles Pract Telemed E Health. 2008;131:23–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyler SE. Gangure DP. Legal and ethical challenges in telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10:272–276. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Telemedicine for CSHCN: A state-by-state comparison of Medicaid reimbursement policies and Title V activities. Gainesville, FL: Institute for Child Health Policy, University of Florida; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Telehealth services fact sheet. Rockville, MD: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, American Medical Association; 2009. [Jan 30;2013 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Telemedicine reimbursement report. Washington, DC: 2003. [Jan 30;2013 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cwiek MA. Rafiq A. Qamar A, et al. Telemedicine licensure in the United States: The need for a cooperative regional approach. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13:141–147. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tracy J. Rheuban K. Waters RJ, et al. Critical steps to scaling telehealth for national reform. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:990–994. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagnild G. Leenknecht C. Zauher J. Psychiatrists' satisfaction with telepsychiatry. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12:546–551. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.S. 1533 (107th): Health Care Safety Net Amendments of 2002. 2002. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/107/s1533. [Jan 30;2013 ]. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/107/s1533

- 42.Thompson JN. The future of medical licensure in the United States. Acad Med. 2006;81(12 Suppl):S36–S39. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000243351.57047.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Litchfield SM. Update on the nurse licensure compact. AAOHN J. 2010;58:277–279. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20100625-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Administrator NLC. Nurse licensure compact (NLC) https://www.ncsbn.org/nlc.htm. [Jul 31;2010 ]. https://www.ncsbn.org/nlc.htm

- 45.Schlachta-Fairchild L. Varghese SB. Deickman A. Castelli D. Telehealth and telenursing are live: APN policy and practice implications. J Nurse Pract. 2010;6:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson J. Doze S. Urness D, et al. Evaluation of a routine telepsychiatry service. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7:90–98. doi: 10.1258/1357633011936219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tracy J, editor. A guide to getting started in telemedicine. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri School of Medicine; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgiss SG. Telehealth technical assistance manual. Kansas City, MO: National Rural Health Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gagnon M-P. Godin G. Gagne C, et al. An adaptation of the theory of interpersonal behaviour to the study of telemedicine adoption by physicians. Med Inform. 2003;71:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gagnon M-P. Lamothe L. Fortin J-P, et al. Telehealth adoption in hospitals: An organizational perspective. J Health Organ Manage. 2006;19:32–56. doi: 10.1108/14777260510592121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yellowlees P. Succesful development of telemedicine systems—Seven core principles. J Telemed Telecare. 1997;3:215–222. doi: 10.1258/1357633971931192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prinz L. Cramer M. Englund A. Telehealth: A policy analysis for quality, impact on patient outcomes, and political feasibility. Nurs Outlook. 2008;56:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demiris G. Integration of telemedicine in graduate medical informatics education. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:310–314. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carroll M. James JA. Lardiere M, et al. Innovation networks for improving access and quality across the healthcare ecosystem. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:107–111. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Title XIII: Health Information Technology. 2009. http://www.hca.wa.gov/arra/documents/state_hie_challenge_funding_opportunity_announcement_120210.pdf. [Jan 30;2013 ]. http://www.hca.wa.gov/arra/documents/state_hie_challenge_funding_opportunity_announcement_120210.pdf

- 56.Ways and Means Committee. Medicare Telehealth Enhancement Act of 2009. 2009. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr2068. [Jan 30;2013 ]. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr2068

- 57.Ackerman MJ. Filart R. Burgess LP, et al. Developing next-genaration telehealth tools and technologies: Patients, systems, and data perspectives. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:93–95. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Demiris G. Edison K. Schopp LH. Shaping the future: Needs and expectations of telehealth professionals. Telemed J E Health. 2004;10(Suppl 2):S60–S63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jennett PA. Andruchuk K. Telehealth: 'Real life' implementation issues. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2001;64:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(00)00136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gawande A. The checklist manifesto: How to get things right. New York: Macmillan; 2009. [Google Scholar]