Abstract

Objective:

To test the effects of a novel cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)–based intervention delivered by a nurse therapist to patients with Parkinson disease (PD) with clinically significant impulse control behaviors (ICB).

Methods:

This was a randomized controlled trial comparing up to 12 sessions of a CBT-based intervention compared to a waiting list control condition with standard medical care (SMC). A total of 27 patients were randomized to the intervention and 17 to the waiting list. Patients with a Mini-Mental State Examination score of <24 were excluded. The coprimary outcomes were overall symptom severity and neuropsychiatric disturbances in the patients and carer burden and distress after 6 months. Secondary outcome measures included depression and anxiety, marital satisfaction, and work and social adjustment in patients plus general psychiatric morbidity and marital satisfaction in carers.

Results:

There was a significant improvement in global symptom severity in the CBT intervention group vs controls, from a mean score consistent with moderate to one of mild illness-related symptoms (χ2 = 16.46, p < 0.001). Neuropsychiatric disturbances also improved significantly (p = 0.03), as did levels of anxiety and depression and adjustment. Measures of carer burden and distress showed changes in the desired direction in the intervention group but did not change significantly. General psychiatric morbidity did improve significantly in the carers of patients given CBT.

Conclusions:

This CBT-based intervention is the first to show efficacy in ICB related to PD in terms of patient outcomes. The hoped-for alleviation of carer burden was not observed. The study demonstrates the feasibility and potential benefit of a psychosocial treatment approach for these disturbances at least in the short term, and encourages further larger-scale clinical trials.

Classification of evidence:

The study provides Class IV evidence that CBT plus SMC is more effective than SMC alone in reducing the severity of ICB in PD, based upon Clinical Global Impression assessment (χ2 = 16.46, p < 0.001): baseline to 6-month follow-up, reduction in symptom severity CBT group, 4.0–2.5; SMC alone group, 3.7–3.5.

Impulse control disorders (ICD) are a group of psychiatric conditions linked by their repetitive reward-based behaviors. Their core feature is the failure to resist an impulse, drive, or temptation to perform an act harmful to either self or others.1 The term has been adopted for use in Parkinson disease (PD) for a range of conditions that include pathologic gambling, compulsive shopping, compulsive eating, sexual behavior, punding, and dopamine medication overuse, also known as dopamine dysregulation syndrome.2,3 Because of difficulties in the application of standard and consistent criteria across the range of problems, the term impulse control behaviors (ICB) is preferred to describe this set of problematic behaviors. ICB are thought to be drug-related effects of dopamine replacement therapies and occur in 14% of patients.4 PD-ICB are associated with high levels of neuropsychiatric comorbidity and carer burden or distress5,6 and can have serious financial and other social consequences. There are no reliable evidence-based treatments and development of psychosocial interventions has been neglected.7 The usual clinical approach is an attempt at reducing/substituting or withholding dopamine replacement therapies. However, the behaviors may persist despite reduction, and many patients fail to tolerate the medication adjustments because they develop off-period dysphoria or worsening PD motor symptoms.8,9 Similarly, mixed results in terms of ICB have been seen following surgical interventions in PD such as deep brain stimulation.10,11

In the general population, psychological interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be used to address ICB such as pathologic gambling.12,13 The aim of this current study was to undertake a randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a CBT-based, psychosocial intervention in PD-ICB with groups randomly assigned to receive the intervention or to be placed on a waiting list while continuing with standard medical care (SMC). We hypothesized that treatment would lead to a reduction in 1) ICB severity in the patient and 2) burden and strain on the caregiver, in those allocated to the intervention when compared to those on the waiting list.

METHODS

Study design, registration, and consents.

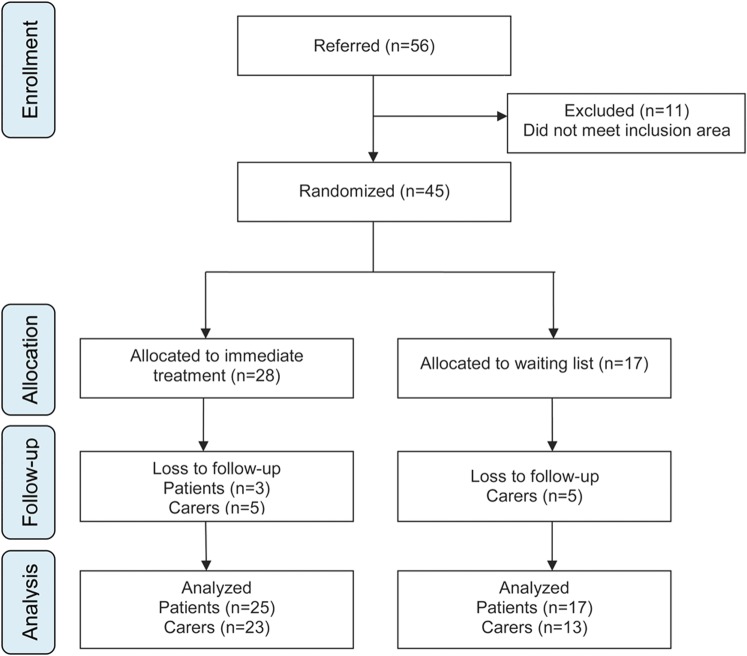

The study was approved by the National Research Ethical Committee (ref. no.: 08/H0807/1). Separate written informed consent for treatment was obtained from patient and carer. This trial is registered with isrctn.org (ISRCTN 82636004). The design was a pilot study conducted in a prospective, randomized, controlled fashion. We followed CONSORT reporting guidelines (figure). The primary research question was whether CBT plus SMC was superior to SMC alone in reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with PD with ICB, to be answered at Class IV level of evidence.

Figure. Trial profile showing participant flow.

Participants.

The research was based at the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, and King's College Hospital NHS Trust Regional Neurosciences Centre, SE London. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of idiopathic PD according to UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank criteria14 and associated ICB which had failed to remit despite standard measures taken by the treating neurologist, including medication changes. ICB were initially screened for using the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Behaviors in Parkinson's Disease (QUIP).15 Following a positive screening, ICB were confirmed in a clinical interview conducted which made use of DSM-IV criteria for pathologic gambling, along with other criteria for the ICB in question by a member of the research team.1,16–18 Exclusion criteria were standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)19 scores <24, non-English speakers, and those without an identifiable carer able to participate in the trial.

Randomization.

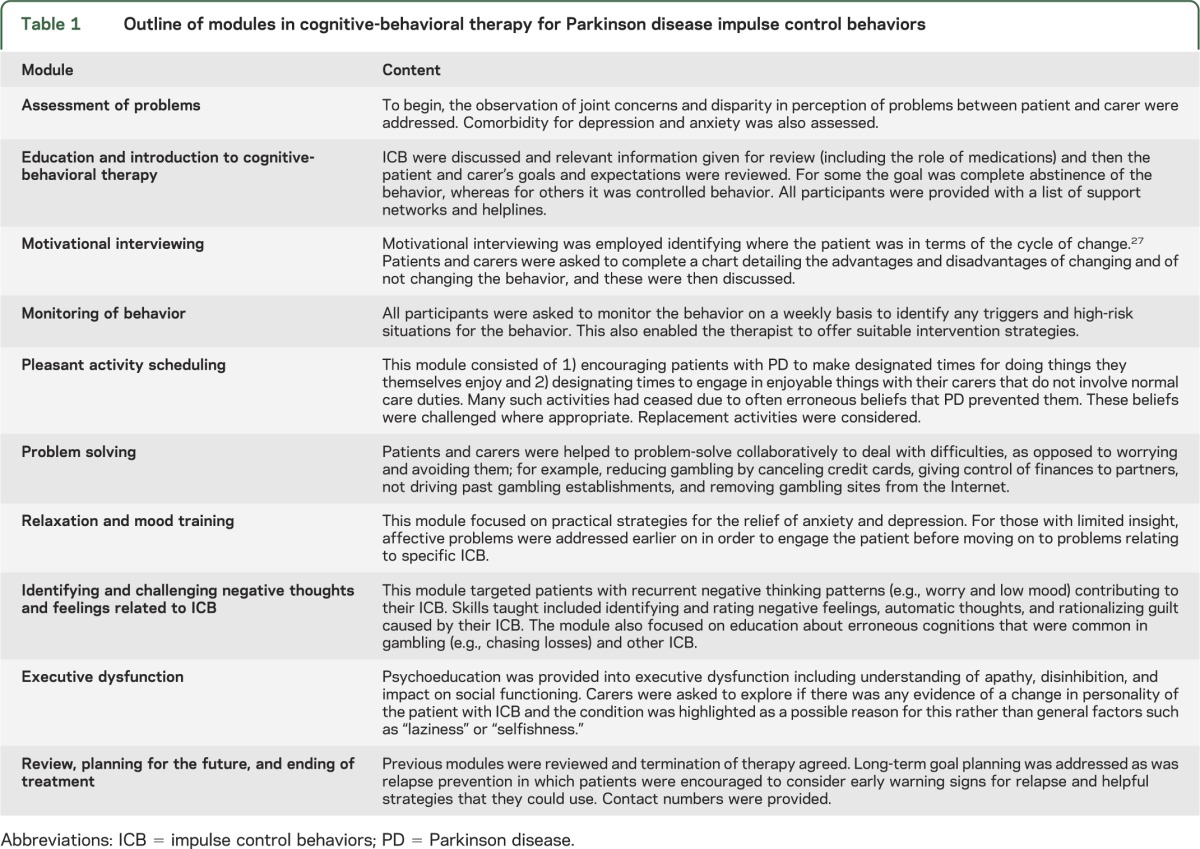

Eligible consenting participants were randomly assigned to immediate treatment (treatment group) or a 6-month waiting list (waitlist group). Randomization was via random number tables held independently of those performing the initial clinical assessment. Once randomized, the participant, clinician, family doctor, and PD nurse specialist were informed of participation in the trial. Those randomized into the treatment group commenced the CBT intervention immediately (table 1), with intention to see people weekly for 12 sessions of treatment. Patients and raters were aware of group allocation following randomization.

Table 1.

Outline of modules in cognitive-behavioral therapy for Parkinson disease impulse control behaviors

Treatments.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy–based intervention.

A treatment manual had been compiled during the pilot phase of the trial and informed by current published treatment of ICB in the general population adapted for PD, with additional components on communication and interpersonal relationships in relation to carers, executive dysfunction, and elements of case management. Therapy was given by the same nurse therapist (S.A.J.) supervised by a consultant clinical psychologist (R.B.). Individual therapy supervision was provided once every 4 weeks and included review to ensure manual adherence, fidelity, and quality. Therapy usually took place in patients' homes, although some sessions were done in clinic. Notes were made on themes discussed in every session along with record of number of treatment sessions attended, active withdrawals from treatment, and dropout at follow-up.

Standard medical care.

All participants received information leaflets about treatments in PD and potential adverse effects. Those randomized to the waiting list control received SMC and waited 6 months before receiving the intervention (results of which to be reported separately). Standard treatment included ongoing review by the patient's primary care physician, PD nurse specialist, and in many cases review by a geriatric physician or neurologist. SMC did not preclude clinically indicated adjustments to medication or specialist referrals but physicians were asked to keep medication constant if possible.

Outcome measures.

The coprimary outcome measures in patients were the clinician-rated Clinical Global Impression (CGI) of symptom severity, the CGI of change,20 and the Neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI), based on a structured interview with the carer.21 The CGI is a general measure which covers the impact of ICB. Similarly, the NPI covers many behaviors but includes items on disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, and appetite and eating changes, which are directly relevant to ICB. Secondary outcome measures included the patient-rated Work and Social Adjustment Scales,22 the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)–28,23 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),24 Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),25 and the Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State (GRIMS).26 At the time of study design, there were no validated scales to measure frequency and impact of ICB behaviors. We therefore developed an Impulse Control Behavior Severity Scale (ICBSS) for this purpose. This is a clinician-rated scale based on a structured interview, designed to measure the frequency (0–4) and impact (0–3) of the following ICB: gambling, shopping, eating, hypersexuality, simple (punding) or complex (hobbyism) repetitive behaviors, and compulsive overuse of medication. A single multiplicative score between 0 and 12 is derived for each behavior with a summative score as a result of addition for each ICB (0–72). The scale covers the preceding 6 months although ratings focus on the last month. Higher scoring represents more severe ICB behavior. Disease severity was assessed with the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and Hoehn & Yahr stage27; levodopa and dopamine agonist doses were converted to levodopa equivalent daily doses.28

For carers, coprimary outcome measures were the Zarit Burden interview, which is a caregiver-rated scale,29 and the total distress score on the NPI. The majority of carers were spouses or children. Secondary measures included GHQ-28 and the GRIMS. The face-to-face assessments were undertaken by the researcher (D.O.), who was not blind to treatment allocation but was independent of the treating team. Those measures that were self-rated were sent to the patient prior to the clinical assessment.

Measures for primary and secondary endpoints were performed at baseline (T0), at a fixed point 6 months from initiation of treatment (T+6), or 6 months on the waiting list control. Patients receiving treatment received an additional assessment at the end of treatment if that happened before 6 months. In some, the T+6 assessment was not possible, in which case the end of treatment assessment was used for analysis of outcome.

Sample size calculation.

In the absence of informative evidence from other CBT interventions, we based our sample size on a recent CBT study for PD carers, which showed improvement of approximately one standard effect size30 in psychopathology (mean reduction on the GHQ of 20.7 [SD 14.5] compared to 6.8 [SD 13.9] for controls). From this we estimated we would need 17 participants in each group to show a difference with 80% power and α set at 0.05.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were under the guidance of a consultant statistician at the Institute of Psychiatry and used SPSS 17 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The analysis of primary and secondary outcome measures was based on the difference between groups (treatment vs waitlist) at time points T0 and T+6 on the basis of intention to treat. This was via a 2-way analysis of covariance that included baseline scores. Treatment effect was tested by a 2-sided test at a significance level of 5%. Effect sizes were calculated using partial η2. Values up to 0.10 denoted small, 0.25 medium, and 0.40 large effect sizes.31

RESULTS

Participants.

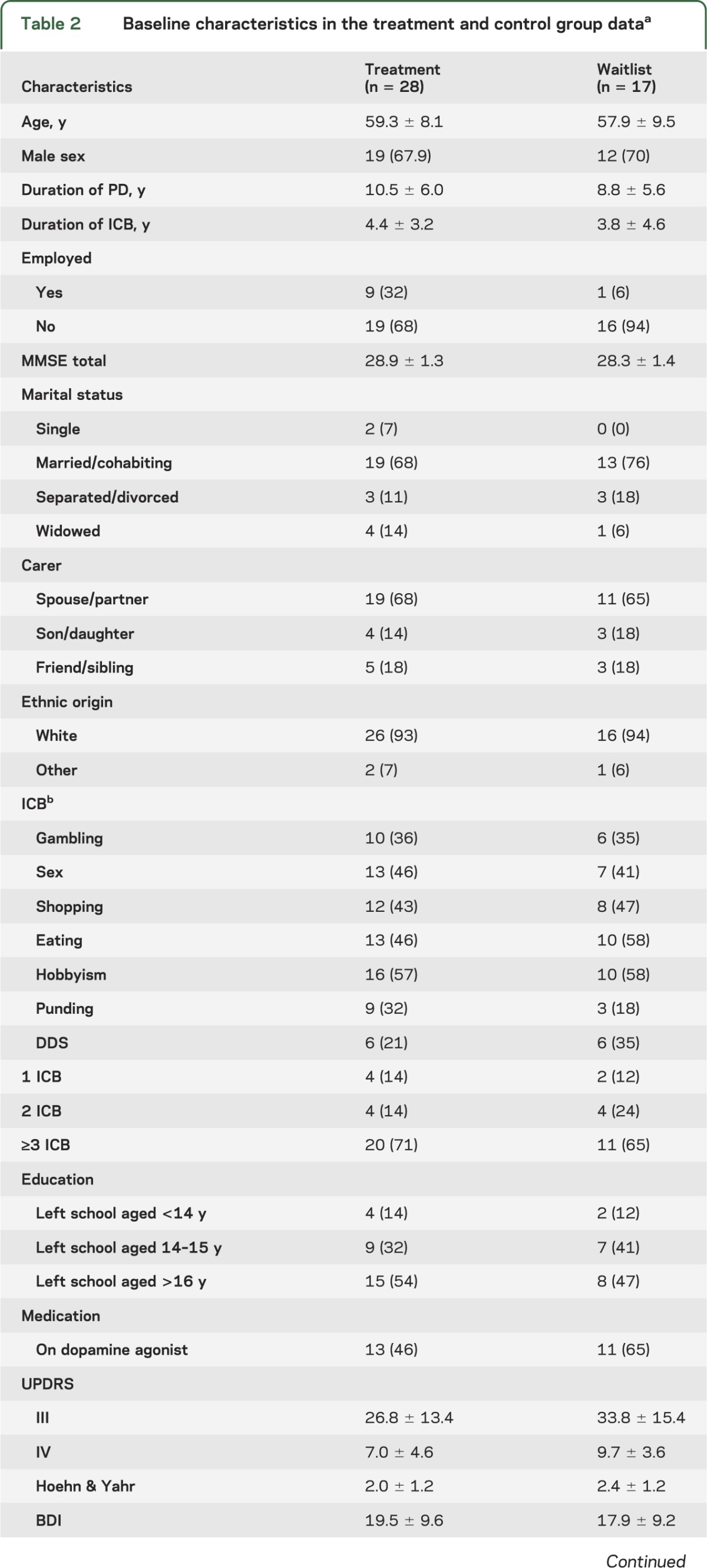

Between August 1, 2008, and August 1, 2011, 45 eligible patients consented (figure); 28 (62%) were randomized to immediate treatment and 17 (38%) to the waiting list. Baseline characteristics are presented in table 2. There were no significant differences between groups based on demographic and clinical characteristics, nor was there a difference in use of dopamine agonists or levodopa equivalent dose. Most of the sample were young men who had had more than 3 ICB for several years. All patients in the treatment group completed at least one session and were included in the analysis; 58% completed all 12 sessions with 88% completing at least 6 sessions (range 1–12). Mean levels of levodopa equivalent daily doses and total UPDRS scores were similar across treatment groups and remained stable over the course of treatment (table 2).

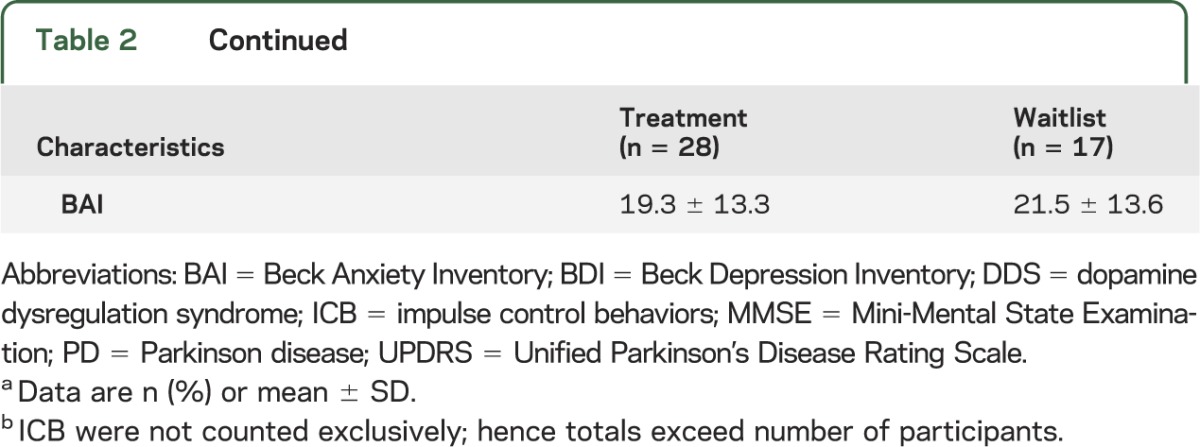

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics in the treatment and control group dataa

Primary outcomes: Patient symptoms and behavior.

There was a significant treatment effect with respect to changes in global levels of symptom severity using the CGI as a continuous measure with a reduction from a mean score consistent with moderate illness-related symptoms to a score consistent with mild illness-related symptoms. There was also significant benefit when comparing CGI improvement categories [χ2 (1) = 16.46, p < 0.001]. A total of 75% were improved in the treatment group, compared to 29% in the waitlist group.

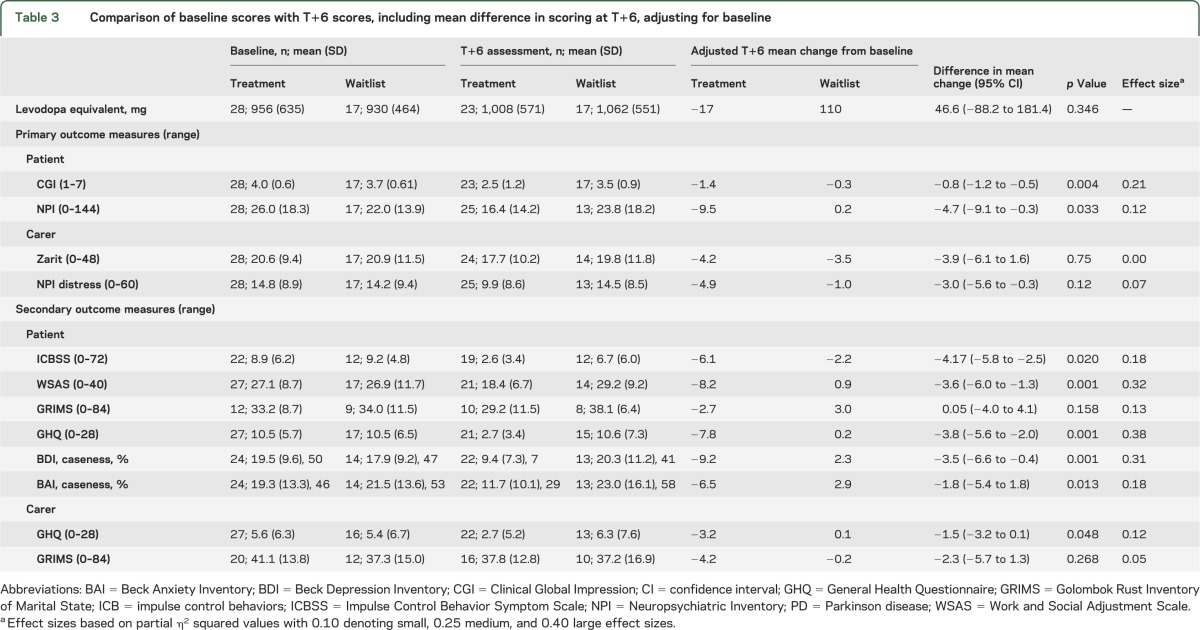

The NPI also indicated improvement in total behavioral disturbance compared to baseline in the intervention group, with a significant reduction in psychopathology in favor of treatment (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline scores with T+6 scores, including mean difference in scoring at T+6, adjusting for baseline

Secondary outcomes: Patient.

The frequency and impact of the ICB was significantly reduced over the 6-month period in the treatment group. One of the authors (A.S.D.), blinded to group allocation, independently assessed audiotapes of the ICBSS measures on a subset of patients (n=8; 19%). Weighted kappa for interrater reliability of scoring was 0.874 (95% confidence interval 0.722 to 1.000) (second rater blind to allocation). At T+6, 44% of the treatment group no longer met QUIP criteria for any ICB compared to 29% in the waitlist group at 6 months. Work and Social Adjustment Scale demonstrated a significant treatment effect in areas of disability at work, home, leisure activities, and interpersonal relationships. There was no significant difference in GRIMS between allocated groups with scores in the subset of partnered relatives.

Additionally, there was improvement in measures of anxiety (BAI) and depression (BDI) in the treatment group at T+6, which reduced from moderate to mild severity. A total of 8% scored above the clinical threshold for depression (i.e., moderate to severe; score ≥19) on the BDI in the treatment group in comparison to 41% in the waitlist group. Additionally 29% scored above the clinical threshold for anxiety (BAI ≥16) in the treatment group for anxiety in comparison to 59% in the waitlist group.

Primary outcomes: Carer burden and distress.

No significant benefit to carer burden or carer distress was found in the treatment group using the ZARIT and NPI carer distress measures.

Secondary outcomes: Carer.

GHQ-28 scores were significantly better in the treatment group. This group scored below the level for caseness following the intervention (a score of ≤4) indicating reduced levels of anxiety and depression. The GRIMS indicated no significant treatment effect on carers' perception of the quality of their relationship, with mean scores consistent on the scale with a rating of “poor.”

Adverse outcomes.

There were no serious adverse events attributable to the trial.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that a CBT-based intervention is clinically effective in the treatment of ICB in PD although it draws on techniques developed for ICB in the general population. The use of a mix of self-report and clinician-rated measures enabled estimation of measures important to patient, carer, and clinician, the majority of which improved significantly. Additionally, the intervention appeared to decrease psychiatric morbidity in the carers of patients with PD ICB. Our study also shows that spontaneous recovery from these harmful behaviors in PD which persist after optimization of medication is rare. To our knowledge, the only other relevant study is a recent trial of amantadine which led to a reduction in pathologic gambling,32 which awaits confirmation. Moreover, in a large cross-sectional study of ICB, amantadine use was associated with a higher incidence of at least one active ICB when compared to no amantadine use.33

In addition to ICB-specific measures, the CBT-based intervention also seemed to benefit depression and anxiety, which are commonly reported comorbidites,6 as well as measures relating to work and social function. These findings are in keeping with a conceptual model which makes dysphoria a central component of PD-ICB.8 Low mood, anxiety, and loss or avoidance of previously rewarding activities may be important factors in the maintenance of ICB, making them valid targets within treatment. For example, increasing purposeful day-to-day activity could relieve dysphoria and increase enjoyment in neglected pastimes, while reducing the time spent on and need for ICB-related behaviors.

While the intervention proved effective in reduction of psychological symptoms in patients with PD, we did not demonstrate an improvement in our primary outcome measures of carer burden or distress, although changes were in the desired direction. The secondary outcome of carer psychiatric morbidity (GHQ) did show significant improvement. A recent study demonstrated patient depression and levodopa end-of-dose dysphoria to be most predictive of carer burden in a PD ICB sample.5 Improvement in patient depression scores occurred without any changes in dopamine replacement therapies in our study, but this was not associated with a reduction in carer-rated burden. It is possible that a longer follow-up period would be required to demonstrate change in perceptions of burden by carers, especially in couples where the ICB had been going for many months or years.

Although the results are encouraging, several limitations apply. The study was small and designed to test the feasibility of a large-scale multicenter trial. The sample size and 6-month duration of follow-up limit the conclusions that can be drawn. However, the observation of impact on a range of patient indices relating to differing aspects of outcome suggests that the findings are reliable. A further limitation of sample size was that it precluded detailed examination of factors that may predict individual response to treatment. The intervention appeared to be acceptable and well-tolerated and dropouts were few.

Regarding trial design, referrals were made from a variety of sources but information was not systematically collected on the total number of potentially eligible cases or on those who declined the offer of referral to the trial. Patients with greater severity or those with less insight may have been excluded. Furthermore, it was not possible to maintain blindness to group allocation from the assessor or patient, which may have led to reporting bias in favor of the intervention group. This is offset to some extent by the use of self-report measures and a high level of inter-rater reliability in the evaluation of outcome. Additionally, the study did not include an active control condition, relying on a comparison between the intervention and waiting list (plus SMC). This control condition was, however, reflective of current clinical practice in PD ICB as it stands, given the absence of an evidence base for management options for this complex range of conditions.

The follow-up duration of 6 months was on average 2 months after end of treatment. Future studies would provide a more clinically useful picture of treatment efficacy with follow-up for at least a year with note of factors such as relapse or new onset ICB in the intervention group. In addition, further work could investigate what proportion of clinical improvement was due to the CBT component and how much was due to other aspects of the psychosocial intervention.

Finally, the present study was able to demonstrate treatment efficacy in patients with PD-ICB, a condition associated with considerable morbidity and distress. Future work will also need to consider cost effectiveness and questions of treatment delivery. That is, who is best placed to deliver the intervention—a psychiatric nurse with training in CBT, a PD nurse specialist, another health care professional, or even lay group, and the extent of training and supervision required.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Ulrike Naumann and Daniel Stahl for help with data analysis and Dr. Romi Saha (neurologist), Michelle McHenry, Amanda Scutt, and Sue Jacobs (Parkinson disease nurse specialists), as well as all the other clinicians, patients, and families who participated in the trial.

GLOSSARY

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- CBT

cognitive-behavioral therapy

- CGI

Clinical Global Impression

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition

- GHQ

General Health Questionnaire

- GRIMS

Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State

- ICB

impulse control behaviors

- ICD

Impulse control disorders

- ICDSS

Impulse Control Behavior Symptom Scale

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NPI

Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- PD

Parkinson disease

- QUIP

Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Behaviors in Parkinson's Disease

- SMC

standard medical care

- UPDRS

Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale

Footnotes

Editorial, page 782

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was designed by A.S.D., R.G.B., and M.S. Data were collected by D.O., S.A.J., and J.M. K.R.C., S.O.S., and A.M. contributed to participant recruitment. D.O., A.S.D., R.G.B., S.A.J., and M.S. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis, the integrity of the data, and the decision to submit the paper for publication. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The major drafting of the manuscript was by D.O., R.G.B., and A.S.D.

STUDY FUNDING

The project was funded by Parkinson's UK. The authors receive salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre (A.S.D., R.G.B., K.R.C.) and Dementia Biomedical Research Unit (R.G.B.) at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London.

DISCLOSURE

D. Okai and S. Askey-Jones report no disclosures. M. Samuel has received honoraria for lectures/educational material form UCB and Medtronic; has received unrestricted educational grants from Solvay and Ipsen; and received funding for educational trips from Ipsen, Medtronic, and UCB. S. O’Sullivan has received funding for travel from UCB and Britannia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. K. Chaudhuri serves on scientific advisory boards for Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; and receives research support from UCB, Schwarz Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Britannia Pharmaceuticals, and Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A. Martin and J. Mack report no disclosures. R. Brown receives grant support for the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) UK, Parkinson's UK, and the Alzheimer's Research Trust. A. David has received travel expenses and honoraria for speaking and educational activities from Janssen-Cilag; serves on advisory boards for Eli Lilly, UCB, and Novartis; is coeditor of Cognitive Neuropsychiatry; and receives research funding from NIHR UK, Parkinson's UK, and the Medical Research Council (UK). Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovannoni G, O'Sullivan JD, Turner K, Manson AJ, Lees AJL. Hedonistic homeostatic dysregulation in patients with Parkinson's disease on dopamine replacement therapies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:423–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim S-Y, Evans AH, Miyasaki JM. Impulse control and related disorders in Parkinson's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 2008;1142:85–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol 2010;67:589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leroi I, Harbishettar V, Andrews M, et al. Carer burden in apathy and impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Int J Ger Psychiatry 2012;27:160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voon V, Sohr M, Lang AE, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a multicenter case–control study. Ann Neurol 2011;69:986–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaney M, Leroi I, Simpson J, Overton PG. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: a psychosocial perspective. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2012;19:338–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okai D, Samuel M, Askey-Jones S, David AS, Brown RG. Impulse control disorders and dopamine dysregulation in Parkinson’s disease: a broader conceptual framework. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:1379–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinak CA, Nirenberg MJ. Dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2010;67:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shotbolt P, Moriarty J, Costello A, et al. Relationships between deep brain stimulation and impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease, with a literature review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim S-Y, O'Sullivan SS, Kotschet K, et al. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome, impulse control disorders and punding after deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson's disease. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:1148–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sylvain C, Ladouceur R, Boisvert JM. Cognitive and behavioural treatment of pathological gambling: a controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997;65:727–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milton S, Crino R, Hunt C, Prosser E. The effect of compliance-improving interventions on the cognitive-behavioural treatment of pathological gambling. J Gambl Stud 2002;18:207–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes AJ, Ben-Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, Lees AJ. What features improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis in Parkinson's disease: a clinicopathologic study. Neurology 2001;57:S34–S38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weintraub D, Hoops S, Shea JA, et al. Validation of the questionnaire for impulsive-compulsive disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2009;24:1461–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans AH, Katzenschlager R, Paviour D, et al. Punding in Parkinson's disease: its relation to the dopamine dysregulation syndrome. Mov Disord 2004;19:397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voon V, Fox SH. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviours in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1089–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence AD, Evans AH, Lees AJ. Compulsive use of dopamine replacement therapy in Parkinson's disease: reward systems gone awry? Lancet Neurol 2003;2:595–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molloy D, Alemayehu E, Roberts R. Reliability of a Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination compared with the traditional Mini-Mental State Examination. Alzheimers Dis Assoc Disord 1991;5:206–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Global Impressions. In: Guy W, ed. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, rev ed. Rockville: NIMH; 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JM. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg DP, Hillier V. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 1979;9:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory—II. San Antonio: Psych Corp; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck A, Steer R. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio: Psych Corp; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rust J, Bennun I, Crowe M, Golombok S. The Golombok Rust inventory of marital state (GRIMS). Sex Marital Ther 1986;1:55–60 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fahn S, Elton R, Committee UD, eds. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:2649–2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986;26:260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Secker DL, Brown RG. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for carers of patients with Parkinson's disease: a preliminary randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:491–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas A, Bonanni L, Gambi F, Di Iorio A, Onofrj M. Pathological gambling in Parkinson disease is reduced by amantadine. Ann Neurol 2010;68:400–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weintraub D, Sohr M, Potenza MN, et al. Amantadine use associated with impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease in cross-sectional study. Ann Neurol 2010;68:963–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.