Abstract

Background

EBV DNA is found within the malignant cells of 10% of gastric cancers. Modern molecular technology facilitates identification of virus-related biochemical effects that could assist in early diagnosis and disease management.

Methods

In this study, RNA expression profiling was performed on 326 macrodissected paraffin-embedded tissues including 204 cancers and, when available, adjacent non-malignant mucosa. Nanostring nCounter probes targeted 96 RNAs (20 viral, 73 human, and 3 spiked RNAs).

Results

In 182 tissues with adequate housekeeper RNAs, distinct profiles were found in infected versus uninfected cancers, and in malignant versus adjacent benign mucosa. EBV-infected gastric cancers expressed nearly all of the 18 latent and lytic EBV RNAs in the test panel. Levels of EBER1 and EBER2 RNA were highest and were proportional to the quantity of EBV genomes as measured by Q-PCR. Among protein coding EBV RNAs, EBNA1 from the Q promoter and BRLF1 were highly expressed while EBNA2 levels were low positive in only 6/14 infected cancers. Concomitant upregulation of cellular factors implies that virus is not an innocent bystander but rather is linked to NFKB signaling (FCER2, TRAF1) and immune response (TNFSF9, CXCL11, IFITM1, FCRL3, MS4A1 and PLUNC), with PPARG expression implicating altered cellular metabolism. Compared to adjacent non-malignant mucosa, gastric cancers consistently expressed INHBA, SPP1, THY1, SERPINH1, CXCL1, FSCN1, PTGS2 (COX2), BBC3, ICAM1, TNFSF9, SULF1, SLC2A1, TYMS, three collagens, the cell proliferation markers MYC and PCNA, and EBV BLLF1 while they lacked CDH1 (E-cadherin), CLDN18, PTEN, SDC1 (CD138), GAST (gastrin) and its downstream effector CHGA (chromogranin). Compared to lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the uterine cervix, gastric cancers expressed CLDN18, EPCAM, REG4, BBC3, OLFM4, PPARG, and CDH17 while they had diminished levels of IFITM1 and HIF1A. The druggable targets ERBB2 (Her2), MET, and the HIF pathway, as well as several other potential pharmacogenetic indicators (including EBV infection itself, as well as SPARC, TYMS, FCGR2B and REG4) were identified in some tumor specimens.

Conclusion

This study shows how modern molecular technology applied to archival fixed tissues yields novel insights into viral oncogenesis that could be useful in managing affected patients.

Keywords: Gastric adenocarcinoma, Epstein-barr virus, RNA expression profile, Stromal cells, Pharmacogenetic test

Background

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of global cancer mortality with nearly one million new cases per year [1,2]. Approximately ten percent of gastric adenocarcinomas are Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infected, and EBV is considered a class 1 oncogenic pathogen by the World Health Organization [3-6]. Incidence is rising for those cancers in the proximal segment of the stomach (cardia, corpus) where EBV is more frequently involved [7-14].

Recent data from the National Cancer Institute’s cancer surveillance program shows a worrisome rise in gastric cancer incidence among young adults in the US [7,8,15]. Emerging targeted therapy makes it all the more important to identify infected cancers and to characterize biochemical defects such as ERBB2 overexpression that increases likelihood of response to trastuzumab in metastatic gastric cancer patients [16-18]. EBV-infected compared to uninfected gastric cancer has a favorable prognosis [19], and clinical trials are beginning to explore virus-targeted therapy such as 1) infused EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells or NK cells [20-23], 2) reversing the EBV-related methylator phenotype [24], 3) triggering lytic viral replication that could then incite the body’s innate and adaptive immune responses to kill infected tumor cells [25-33], and 4) lytic induction therapy co-administered with antiviral nucleoside analog such as gancyclovir that is phosphorylated and thus activated by viral kinases promoting cytotoxicity [34-41].

Clinical trials examining the efficacy of targeted therapy would benefit from laboratory assays that help identify candidates likely to respond, and could benefit from laboratory assays that signify the effect of intervention on the intended biochemical pathways. Modern molecular technology now permits clinical-grade analysis of multiple pertinent analytes via RNA expression profiling [42]. Device manufacturers have produced sensitive, specific and customizable probe arrays to simultaneously measure multiple RNAs, including non-coding RNAs like EBV-encoded RNA 1 or 2 that are abundantly expressed in infected tumors. Recent progress in quality assurance strategies have matured to the point that RNA expression profiles are being implemented in clinical laboratory settings [42].

To be practical in clinical settings, an assay must be applicable to routinely collected specimens such as archival, paraffin-embedded tissue [42]. In the current study, we measured viral and human gene expression in archival gastric cancers and in adjacent mucosa and controls to develop a test systems that might be used to reliably characterize signatures predictive of response to targeted therapy. A 96-RNA array test system that we dub the Gastrogenus v1™ panel was customized to measure pertinent latent and lytic viral RNAs alongside clinically relevant human mRNAs that were previously reported to be 1) gastric cancer specific, 2) indicative of inflammation, and/or 3) predictive of response to specific medications. These assays, as well as spiked and endogenous control RNAs, were measured in macrodissected paraffin sections using the Nanostring nCounter test system [43-45]. Correlative histologic and molecular studies were done to demonstrate that the test system performed as expected. Our findings show that EBV-related cancers express more latent and lytic transcripts than were previously recognized, and that infected cancers have unique biologic characteristics compared with uninfected cancers. Two major subtypes of cancer were found, implying that gastric cancer early detection strategies or monitoring tests could be tailored to detect the pertinent signatures characterizing major molecular subtypes. Finally, pilot data reveals expression of selected viral and cancer-related genes in adjacent non-malignant mucosa, suggesting a field effect that could be important in cancer development or maintenance.

Results

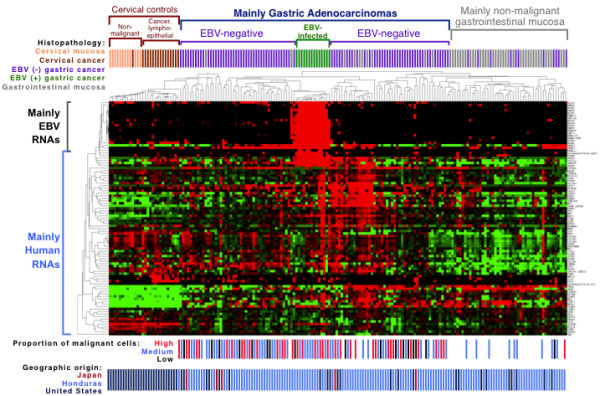

Gene expression profiling was performed on a total of 326 tissues including 187 gastric cancers, 17 lymphoepithelioma-like cervical cancers, and 118 matched non-malignant mucosa from the same surgical procedure (when available). After data normalization, a heat map of the 182 tissues having the best quality RNA, as judged by highest average level of four housekeeping RNAs, revealed patterns of gene expression that differed in gastric versus cervical control tissues. Furthermore, in both the gastric and cervical clusters, malignant and non-malignant tissues tended to cluster together, supporting the ability of the nCounter test system to measure clinically important biologic features. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Expression profiles of 182 tissues for 20 viral genes and 73 human genes. A heat map displays unsupervised hierarchical clustering of each tissue in a separate column, and each RNA in a separate row. The data is median-centered with red indicating relative overexpression and green indicating relative under-expression for each gene. Correlative data above the map indicates histopathologic classification with further subclassification of the gastric cancer cohort into 14 EBV infected and 104 EBV negative cancers based on EBV DNA levels. Below the map, each gastric cancer is categorized by the proportion of malignant cells, and geographic origin of each tissue is shown.

One group of gastric carcinomas overexpressed virtually all of the EBV RNAs. To determine which gastric cancers should be designated as EBV-infected, the 71 tissues with the highest combined levels of EBER1 and EBER2 RNA by Nanostring nCounter array were further examined for EBV genome levels within the same tissue by Q-PCR. There was a linear relationship between the amount of EBER1 and EBER2 RNA and the amount of EBV genome. (See Figure 2.) Our previously established cutoff [46] for the level of EBV genome corresponding to localization of virus to malignant cells resulted in 14 cancers being placed in the EBV-infected category. The remaining gastric cancers were called EBV-negative, and among them the highest recorded RNA levels were 174,016 for EBER1 and 27,972 for EBER2. In contrast, among the EBV-infected gastric cancers the lowest EBER1 level was 263,589 and the lowest EBER2 level was 140,081. Proposed cutoffs for identifying a tissue as EBV-infected are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

EBV-encoded RNA levels are high in infected gastric cancer and are proportion to EBV genome level. A. Box plots of EBER1 and EBER2 in benign and malignant tissues reveal that EBV-infected gastric cancer has substantially higher levels of EBER1 and EBER2 non-coding RNAs than do uninfected cancers and control tissues. Proposed thresholds for EBER1 or EBER2 are shown beyond which a gastric cancer could reliably be designated as EBV-infected. Each dot represents an individual analytic result on a log2 normalized unit (NU) scale. B. Pairwise comparison of EBER1 and EBER2 RNA levels by Nanostring nCounter array and EBV DNA viral load by Q-PCR reveals a linear association between levels of each of these analytes. Pearson correlation coefficients (P >0.86) are shown. The previously validated level of EBV DNA viral load is shown beyond which EBER was always localized to malignant cells by EBER in situ hybridization (threshold of 10,558 EBV genomes per 100,000 cells, which is equivalent to 13.37 on this log2 scale) [46]. Proposed cutoffs for RNA levels are indicated for both EBER1 (200,000 NU, or 17.61 on this log 2 scale) and EBER2 (100,000 NU, or 16.61 on this log2 scale). The one outlier is a non-malignant gastric mucosa that was located adjacent to an EBV-infected gastric cancer, and this mucosa had an EBV DNA load equivalent to that of infected cancers, but it would have been correctly excluded from the EBV-infected cancer group if either EBER1 or EBER2 RNA levels were used, or if histology were used, to screen for EBV-related malignancy.

Genes overexpressed in EBV-infected versus EBV-negative gastric cancer

Twenty eight genes were significantly differentially expressed in EBV-infected cancers compared to the EBV negative gastric cancers (p < 0.05). Interestingly, all 28 were upregulated rather than downregulated in the infected cancers, and this bias is explained at least in part by our selection of positive rather than negative markers of infection when choosing the RNAs to be profiled for this study. Failure to identify any downregulated genes was still surprising given reports that EBV is associated with a CpG island methylator phenotype and additionally the virus can destabilize cellular mRNAs globally [47].

Among the genes significantly upregulated in infected cancers were all 18 of the EBV RNAs tested, as well as cytomegalovirus pp65 (UL83). The cytomegalovirus pp65 (UL83) result is likely to be false positive (suspected to be probe cross hybridization), as evidenced by absence of another lytic RNA, cytomegalovirus pol (UL54), in the EBV-infected cancers. Furthermore, UL83 but not UL54 was expressed in EBV infected but not in EBV-negative cell line controls (data not shown). Another possible explanation for false positive viral RNA expression is probe crossreactivity with viral DNA. Nine human RNAs were significantly upregulated in EBV-infected compared to EBV negative gastric cancers: FCER2, MS4A1 (CD20), PLUNC, TNFSF9, TRAF1, CXCL11, IFITM1, PPARG, and FCRL3. (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multiple human RNAs are over-expressed in EBV-infected gastric cancer compared to EBV-negative cancer. Box plots demonstrate the human RNAs levels in infected compared to uninfected gastric cancers and controls that include lymphoepithelioma-like cervical cancer, cervical mucosa, and benign gastrointestinal mucosa. Each dot represents an individual analytic result on a log2 normalized unit scale.

Genes differentially expressed in gastric cancer compared to non-malignant gastrointestinal mucosa

Twenty six genes were significantly dysregulated in gastric cancer compared to non-malignant gastric mucosa (p < 0.05). The human RNAs upregulated in gastric cancer were INHBA, SPP1, THY1, SERPINH1, CXCL1, FSCN1, COL1A1, SPARC, COL1A2, PTGS2 (COX2), BBC3, ICAM1, TNFSF9, MYC, SULF1, SLC2A1, COL3A1, PCNA, and TYMS, while the downregulated RNAs were CDH1 (E-cadherin), CLDN18, CHGA (chromogranin), PTEN, SDC1 (CD138) and GAST (gastrin). The only viral factor that was differentially expressed was BLLF1 which was significantly higher in cancer than in non-malignant gastric mucosa (p = 0.004). BLLF1 encodes the late viral envelope protein gp350/220, suggesting that virions are significantly more prevalent in cancer than in non-malignant gastric tissue. BLLF1 was not specific for gastric cancer, however, as it was also expressed in some benign and malignant cervical tissues, as well.

Genes associated with gastric cancer compared to lymphoepithelioma-like cervical cancer

Nine genes were significantly dysregulated in gastric cancer compared to lymphoepithelioma-like cervical cancer (p < 0.05). The seven RNAs upregulated in gastric cancer were CLDN18, EPCAM, REG4, BBC3, OLFM4, PPARG, and CDH17, while the two downregulated genes were IFITM1 and HIF1A.

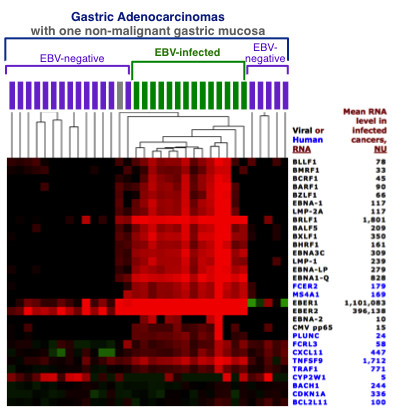

Patterns of latent and lytic viral gene expression in EBV infected gastric cancers

The 14 EBV-infected gastric cancers in this study consistently coexpressed virtually all of the EBV latent and lytic genes, which is somewhat surprising given that prior literature describes a somewhat restricted latency pattern [48-51]. It is feasible that the Nanostring nCounter analytic technology is more sensitive than traditional methods of detection.

The most highly expressed viral RNA was EBER1 at an average of over 1 million normalized units per EBV-infected cancer tissue, followed by EBER2, BRLF1 and EBNA1 from of the Q promoter. EBNA2 was the least expressed viral RNA with a mean expression of only 10 normalized units per infected tissue and EBNA2 was completely absent in 8 of the 14 infected gastric cancers. Patterns of viral gene expression are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Latent and lytic EBV genes are co-expressed in gastric cancer. A portion of the heat map from Figure 1 is displayed in high contrast to decipher relative expression levels of EBV genes in the 14 EBV-infected gastric cancers and surrounding specimens. All tissues are gastric cancers except a single non-malignant gastric mucosa, shown in grey, dissected from the same paraffin block as an EBV-infected gastric cancer. Mean expression level of each RNA in the EBV-infected gastric cancer cohort is shown to the right of each gene symbol.

Geographic origin and tumor cell proportion are not preferentially associated with EBV status of gastric cancer

Below the heat map in Figure 1 is the distribution of gastric cancer cases by geographic origin from Honduras (n = 86), Japan (n = 5), or the United States (n = 17). There was no significant association between geographic origin and EBV-positive versus negative clustering of gastric cancers (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.9), suggesting that geographic origin is not the major driver of hierarchical clustering.

The bottom of Figure 1 also shows the distribution of EBV-infected versus EBV-negative gastric cancers classified by the proportion of malignant cells input into the expression profiling assay. There was no significant association between the proportion of malignant cells and the EBV-infected versus EBV-negative groups of gastric cancer. Surprisingly, the cancer tissues with low malignant cell content did not preferentially cluster with the non-malignant gastric tissues. Cancers with low malignant cell content (1 to 25% malignant cells) were distributed across various segments of the heat map along with cancers with medium (26 to 50%) or high (>50%) malignant cell content (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.5), suggesting that overall transcriptome features outweigh tumor cell proportion as the driver of hierarchical clustering.

Keeping in mind that the lymphoepithelioma-like cervical cancers in this study were rich in lymphoid stroma, as are many EBV-infected gastric cancers, it is remarkable that these two classes of cancer clustered separately from each other and also achieved reasonably good separation from adjacent non-malignant mucosa. For most genes in the panel, there is considerable overlap in levels across disease types. While profiles are more informative and more convincing than are individual transcript results, there is some overlap in profiles as well, signifying that profiling assay results must be correlated with histologic features in order to accurately classify a tissue as benign or malignant.

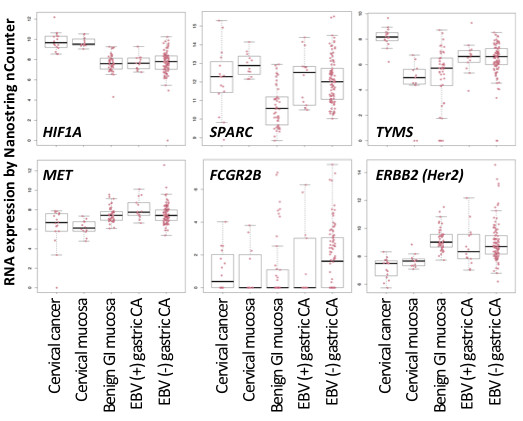

Pharmacogenetic predictors and druggable targets

EBV infection itself is considered an actionable target, at least for the 14/108 (13%) infected gastric cancers we identified. This study demonstrates a novel way to identify virus-infected cancers by RNA profiling of paraffin sections so that prognostic and predictive information may be considered in patient management decisions. Cellular factors of pharmacogenetic potential include the HIF pathway, SPARC, TYMS, FCGR2B, MET, and ERBB2 (Her2). (See Figure 5). Compared with gastric cancers, cervical cancers tend to have higher levels of HIF1A indicating hypoxia response, although equally high levels in non-malignant cervical mucosa raise the possibility of ex vivo stimulation of this oxygen-sensing factor. Further study is needed to distinguish technical factors from in vivo upregulation that would warrant consideration of angiogenesis inhibitors.

Figure 5.

Some gastric cancers have significant dysregulation of factors that show promise as pharmacogenetic predictors. Box plots demonstrate expression of selected pharmacogenetic targets in infected versus non-infected gastric cancers as well as non-malignant gastric mucosa and cervical histopathologies. Each dot represents an individual analytic result on a log2 normalized unit scale.

We confirmed that SPARC is upregulated in gastric cancer compared to benign gastric mucosa. Response to docetaxel, a taxane drug that inhibits mitotic spindle assembly, is reportedly impacted by the amount of SPARC protein expression in gastric cancer [52]. Gastric and cervical cancers both had higher thymydylate synthase (TYMS) than did their respective benign mucosal counterparts. High TYMS levels reportedly contributes to acquired resistance to 5FU combination therapy [53].

A few gastric cancers had extremely high levels of the Fc receptor, FCGR2B, which could affect drug internalization and pharmacodynamics of therapeutic antibodies such as cetuximab in vivo. Four gastric cancers strongly expressed MET, and an additional eight cases strongly overexpressed expressed ERBB2 (Her2), raising the possibility that this assay could predict response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

Discussion

This study used modern molecular methods to examine a large panel human and viral RNAs in gastric cancer. To our knowledge, this is the largest panel of viral gene products to be examined in concert with human RNAs in archival, paraffin embedded tissues. The EBV-infected subtype of gastric cancer is dramatically evident in the corresponding heat map created by unsupervised clustering, and EBV infection was confirmed by high EBV DNA viral loads in these tissues. Expression of selected viral and human genes in the cancers confirmed several known virus- and cancer-related effects and also revealed novel findings that shed light on pathogenesis and possible disease management strategies.

Surprisingly, the infected gastric cancers overexpressed all 18 of the latent and lytic EBV genes that were tested. We discovered high levels of BRLF1 RNA (encoding the immediate early viral protein triggering lytic replication in concert with BZLF1) and moderately high levels of BXLF1 (the viral thymidine kinase that converts penicyclovir to a toxic form, suggesting a mechanism for therapy) [54]. BLLF1 (encoding the late viral envelope protein gp350/220) was expressed at moderate levels that were nevertheless significantly higher than in non-malignant mucosa, suggesting that EBV lytic infection is not abortive but rather is capable of producing the late viral envelope protein gp350/220. Among the latent genes, EBNA1 from the Q promoter, EBNA-LP, and EBNA3C transcripts were most prevalent. EBNA2 was focally detected at low level but was still significantly higher in infected than in uninfected gastric cancers. Prior histochemical work has generally not revealed protein-level expression of the EBNAs or lytic viral gene products, so further work is required to learn if these virally encoding RNAs are localized to malignant cells, lymphocytes, or possibly even to exosomes or virions in the extracellular milieu.

Compared to uninfected cancers, the infected cancers had significant upregulation of nine cellular factors (FCER2, MS4A1 (CD20), PLUNC, TNFSF9, TRAF1, CXCL11, IFITM1, PPARG, and FCRL3), implying that EBV is not an innocent bystander with respect to biochemical impact. The virus-associated changes we found were in pathways known to viral oncologists, namely NFKB and NOTCH signaling (FCER2, TRAF1, PPARG) and mucosal immune response (PLUNC, TNFSF9, CXCL11, IFITM1, FCRL3). MS4A1 (CD20) is B cell specific, reminding us that some of the factors upregulated in EBV-infected compared to uninfected gastric cancers could derive from stromal elements rather than from malignant epithelial cells. PLUNC was previously described as a tumor marker for gastric and nasopharyngeal carcinomas, and it encodes a secreted protein involved in innate immune response [55-57]. TNFSF9, a cytokine of the tumor necrosis factor family, stimulates T cell activation and triggers IFNG production which in turn induces the proinflammatory chemokine CXCL11 and the innate antiviral factor IFITM1. PPARG is as a nuclear receptor controlling glucose metabolism and microtubule networks, and it is a promising target for inhibitory drugs [58]. The FCRL3 immune response gene is mutated in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and Grave’s disease.

Our findings support the work of Lee et al who found distinct human expression patterns in infected versus uninfected gastric cancers [10]. Although their study targeted protein and ours targeted RNA, our findings agreed with theirs for 4 of the 5 factors in common between the two studies (BCL2, PTEN, CDH1, PTGS2). There was a potential discrepancy for ERBB2 that was significantly less frequently expressed in infected compared to uninfected gastric cancers when tested at the protein level [10], whereas the current study showed no significant difference at the RNA transcript level. Confounding factors include 1) the proportion of tumor cells present in the specimens evaluated, 2) different criteria for categorizing expression status, and 3) RNA versus protein targets.

In general, the array technology that was used in this study worked remarkably well in generating RNA profiles that were believable by virtue of distinguishing known benign versus malignant and gastric versus cervical histopathologies. Furthermore, co-expression of analytes in the same pathway or by the same infectious agent makes sense from a pathobiology and virology perspective. Interestingly, all of the cervical tissues clustered together, and benign and malignant cervical lesions were largely segregated even though the Gastrogenus v1™ test panel had not been specifically designed to achieve these endpoints. Lack of multiple co-expressed EBV mRNAs in cervical tissues reinforced what we knew about their EBV-negativity by the gold standard EBER in situ hybridization assay.

Among the seven genes that were significantly more expressed in gastric cancer (regardless of infection status) compared to lymphoepithelioma-like cervical cancer, four were previously reported as gastric cancer markers (CLDN18, REG4, OLFM4, CDH17) [55,59-63]. Two others (EPCAM epithelial cell specific trans-membrane glycoprotein, and PPARG chemokine), as well as REG4, are being explored for targeted cancer therapy [64-66]. The last of the seven, BBC3 (also called p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis, or PUMA) is reportedly upregulated by EBV LMP2A and reigned in by EBV miR-BART5 in cell line models [67,68], suggesting that this BCL2 family member is tightly regulated by the virus.

One of the two RNAs that was significantly higher in cervical compared to gastric cancer was IFITM1, which you may recall was also found to be overexpressed in infected compared to uninfected gastric cancers. Further work is needed to explore if cervical cancers (presumably human papillomavirus-infected) and EBV-infected gastric cancers share a common virus-related mechanism for overexpression of this innate immune response factor. The other gene significantly overexpressed in cervical compared with gastric cancer was HIF1A whose expression was associated with that of four downstream angiogenesis mediators in our panel (VEGFA, SLC2A1, SLC2A3 and EPAS1) as evidenced by positive Pearson’s correlation coefficients (data not shown). If confirmed to be operative in vivo, HIF pathway stimulation implies that angiogenesis inhibitors are worth investigating.

Benign versus malignant gastric tissues tend to cluster separately on the heat map, with some exceptions. Field effect [69] or exosomal transfer of factors to adjacent regions of the local environment [70,71] could explain why some cancers and adjacent reactive tissues had similar profiles. While macrodissection was used to carefully separate benign from malignant lesions, we cannot exclude occult malignancy as a contributor to aberrant clustering.

Among the 19 genes significantly upregulated in gastric cancer compared to adjacent non-malignant gastric mucosa, most were previously reported as gastric cancer specific markers [72-76], and we now confirm that their upregulation is detectable in archival paraffin-embedded tissue. Lower levels of GAST (gastrin) RNA in cancer tissues could help explain the concomitant loss of the gastrin signaling factor CHGA (chromogranin). The most consistently downregulated factor in gastric cancer versus adjacent benign mucosa was the tumor suppressor gene CDH1 (E-cadherin) suggesting either 1) CDH1 promoter hypermethylation [77], 2) rare germline mutation of CDH1 associated with heritable predisposition to gastric cancer [78], or 3) downregulation of CDH1 by EBV LMP1 as described in cell line models [79].

LMP1 was previously reported to be absent in infected gastric cancer except in rare cases [50,51,80,81]. It was therefore surprising that Nanostring nCounter array profiling showed consistent albeit low level expression of LMP1 RNA along with virtually all of the other EBV RNAs that were tested in the infected gastric cancers. Coordinated co-expression of multiple viral genes argues that the expression is true positive. Our microarray results raise the possibility that the viral RNAs we detected are not encoding proteins or that the proteins are 1) only transiently expressed, 2) rapidly degraded, 3) localized to rare cells that are promptly recognized and destroyed by the immune system, or 4) present at such low level that traditional assays are too insensitive to detect them [82]. The nCounter test system manufacturer claims analytic sensitivity equivalent to that of rtPCR [43].

While most viral genes were expressed almost exclusively in the infected gastric cancer cohort, EBER1 and EBER2 were commonly expressed in each one of the benign and malignant gastric and cervical cohorts, albeit at much lower levels than was seen in each of the EBV-infected gastric cancers. Indeed, our study revealed a novel way to identify EBV-infected gastric cancer by measuring EBER1 and/or EBER2 RNA in archival tissue, and we have proposed thresholds that successfully distinguish infected from uninfected gastric cancer.

Support for active viral infection in infected gastric cancer patients comes from serologic evidence of higher titers against viral capsid antigen compared to EBV-negative gastric cancer patients and benign controls [83]. Low level lytic infection was previously described in mucosal lymphoid cells [31,82,84] and in infected gastric epithelial cell lines [85]. BARF1 is known to be expressed in gastric cancer where it is proposed to act as a latent rather than a lytic factor [50,51]. Using sensitive rtPCR technology, multiple EBV lytic transcripts were detected by Luo et al in gastric cancer tissues [50]. Whether active replicative infection occurs in malignant epithelial cells or in lymphoid cells remains uncertain since histochemical stains have failed to reveal a cellular source of lytic factors in gastric tissues [82].

While EBV-infected gastric cancer is biologically distinct from EBV-negative cancer in some respects, the infected counterparts still share many of the classic features previously identified as being characteristic of gastric cancer, such as specific collagens (COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1), SULF1, THY1, SPP1, INHBA, and SPARC[76]. These pan-gastric cancer markers might be exploited for early diagnosis or for monitoring tumor burden during therapy, especially when multiple such markers are tested in concert to maximize specificity while still capturing the heterogeneity of the disease. Biomarkers for the EBV-infected subset, such as EBV DNA and the highly expressed viral EBER1EBER2EBNA1, and BRLF1 RNAs, as well as associated cellular factors confirmed in this study, represent promising targets for early detection. To the extent that any of these factors circulate in blood, they might serve as non-invasive indicators of disease analogous to what has already been achieved for two other EBV-infected neoplasms-- post transplant lymphoproliferative disorder and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In both of these disorders, Q-PCR of circulating EBV DNA facilitates early diagnosis and in monitoring efficacy of therapy [86-88]. High levels of EBER1 and EBER2 RNA were measurable in plasma of 89% of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients [89].

Antiviral therapy is becoming more accepted given its biologic underpinnings-- the viral genome is present in every malignant cell of a given infected cancer-- thus making the virus one of the most appealing therapeutic targets in our armamentarium. Off-the-shelf cytotoxic T cells are now available to treat selected EBV-related malignancies [90,91]. Early clinical trial data demonstrate the merits of lytic induction therapy [33,92,93]. Assessment of lytic induction by panels of tests such as the microarray system described herein could be useful for measuring the biochemical impact of an intervention and its efficacy.

Applicability of the Nanostring nCounter system to archival paraffin embedded tissue was previously reported by others [43,44], but ours is the first study to examine viral and human RNAs in concert. The test system’s ability to rapidly profile multiple RNAs generates rich data relevant to viral oncology and patient care. A major advantage is suitability for routine fixed tissue specimens including small biopsies that were previously collected, processed and stored using customary clinical methods. While microscopy is essential to assuring that representative tissue is input into the assay, the noteworthy flexibility of the test system with regard to malignant cell proportion promotes it use in clinical settings. Panels of analytes could be tailored to support different intended uses such as suitability of a subject for a specific clinical trial, or monitoring efficacy of a given regimen in serial specimens.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the promise of array technology to understand associations between viral and cellular factors in naturally infected gastric cancers. We showed major biologic differences between infected and uninfected cancers, between benign and malignant tissues, and between gastric and cervical cancers. While prior work indicates that the virus lies latent in malignant tissue, we found evidence of active lytic infection and virus-associated cellular changes that should be further explored. Large panels of complementary tests promote confidence in the findings and pave the way for design of practical panels to be applied in clinical trials and, once validated as useful, implemented in routine patient care.

Materials and methods

Patient tissue and macrodissection

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded gastric adenocarcinoma tissues from the clinical archives of three hospitals in disparate parts of the world were assembled, including 30 from the University of North Carolina Hospitals in Chapel Hill, USA, 133 from Western Regional Hospital in Santa de Rosa, Honduras, and 24 from Wakayama Medical University, Wakayama, Japan. As a control, 16 paraffin embedded tissues diagnosed as lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the uterine cervix were retrieved from the archives of the University of North Carolina Hospitals in Chapel Hill. All studies were done with approval of our Institutional Review Board, University of North Carolina Biomedical IRB.

On each paraffin block, nine formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections, each 5uM thick, were cut. One section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin so that a pathologist could mark areas containing at least 50% malignant cells among all cells present. Cancers with less tumor were still included in the study after further categorizing them as having either 1 to 25% or 25 to 50% malignant cells in marked areas of the slide. A scalpel was used to scrape and combine the marked malignant cell-rich areas from 8 unstained sections. When non-malignant mucosa from the same surgical procedure was available, the non-malignant tissue was macrodissected from unstained sections and separately prepared for expression profiling.

Nucleic acid isolation and expression profiling

Total nucleic acid was extracted using the HighPure miR Isolation kit using the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). Nucleic acid quality and purity were assessed by Nanodrop spectrophotometry, and a 500 ng aliquot was spiked with each of three exogenous control RNAs designed by the External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC number 113, 147 and 163) and then frozen until RNA expression analysis on the nCounter system according to manufacturer instructions (Nanostring). Recovery of the spiked ERCC RNAs served as a control for integrity of the stored nucleic acid. Furthermore, recovery of 6 different synthetic RNAs built into the Nanostring reagent system provided confidence that that Nanostring nCounter analytic test system performed as expected.

The instrument generated a direct digital readout of the number of each RNA molecule based on hybridization of patient nucleic acid with multiplexed pairs of capture and reporter probes tailored to each RNA of interest, followed by washing away excess probes, immobilization of biotinylated capture probe-bound RNAs on a surface, and scanning color-coded bar tags on each reporter probe. A custom panel of 96 RNA assays designed for this study included 73 human mRNAs, 7 latent and 9 lytic EBV mRNA transcripts as well as EBER1 and EBER2 non-coding RNAs, two cytomegalovirus mRNAs, and 3 spiked ERCC RNA controls. The target human mRNAs were chosen after literature review to represent the following characteristics, 1) gastric cancer-specific analytes, 2) EBV-dysregulated factors, 3) potential pharmacogenetic biomarkers, 4) inflammatory cell markers, and 4) housekeeping controls. (See Table 1).

Table 1.

RNAs targeted in the GastroGenus v1™ panel

| Gene symbol | Alternate symbol | Function or utility | Reference sequence or GeneID |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gastric cancer specific RNAs and gastrin signalling factors | |||

| REG4 |

|

Cell regeneration and growth |

NM_032044.3 |

| OLFM4 |

|

Tumor growth & cell adhesion, olfactomedin |

NM_006418.3 |

| DKK4 |

|

Embryonic development |

NM_014420.2 |

| ODAM |

APin |

Enamel mineralization |

NM_017855 |

| CSAG2 |

|

Drug resistance |

NM_001080848.2 |

| MIA |

|

Growth inhibition |

NM_006533.2 |

| CYP2W1 |

|

Drug metabolism, cytochrome p450 |

NM_017781.2 |

| HORMAD1 |

|

Cell cycle regulation |

NM_032132.3 |

| MMP10 |

|

Matrix metallopeptidase, remodeling |

NM_002425.2 |

| FUS |

|

mRNA/miRNA processing |

NM_004960 |

| CLDN18 |

|

Tight junction component, claudin |

NM_001002026 |

| SERPINH1 |

|

Collagen synthesis, peptidase inhibitor, heat shock |

NM_004353 |

| THY1 |

|

Control of inflammatory cell recruitment |

NM_006288 |

| INHBA |

|

Inhibin, inhibits hormone secretion and cell growth |

NM_002192 |

| CXCL1 |

|

Immune development and homeostasis, chemokine |

NM_001511 |

| SPARC |

osteonectin |

Protects from apoptosis, docetaxel response |

NM_003118 |

| SPP1 |

|

Osteogenesis, secreted phosphoprotein |

NM_000582 |

| SULF1 |

|

Cell signaling, sulfatase |

NM_015170 |

| COL1A1 |

|

Type I collagen component |

NM_000088 |

| COL1A2 |

|

Type I collagen component |

NM_000089 |

| COL3A1 |

|

Type III collagen component |

NM_000090 |

| CDH1 |

E-Cadherin |

Cell adhesion, mutated in heritable gastric cancer |

NM_004360 |

| EPCAM |

|

Epithelial cell adhesion |

NM_002354 |

| GAST |

|

Stimulates stomach acid secretion |

NM_000805 |

| CDH17 |

|

Peptide transporter, gastrin signalling |

NM_004063.3 |

| CHGA |

|

Neuroendocrine cell, gastrin signalling |

NM_001275 |

| PTGS2 |

COX2 |

Prostaglandin synthesis, gastrin signaling, druggable |

NM_000963.1 |

| MYC |

|

Cell cycle regulator, gastrin signalling |

NM_002467.3 |

| CCND1 |

BCL1 |

cell cycle regulator, gastrin signalling |

NM_053056.2 |

|

EBV-related inflammatory response genes and NFKB signaling factors | |||

| PLUNC |

|

Gastric and nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

NM_130852.2 |

| MET |

|

Receptor tyrosine kinase, ongogene, drug target |

NM_000245.2 |

| BACH1 |

|

Transcription factor |

NM_206866 |

| BBC3 |

PUMA |

p53 target, pro-apoptotic target of EBV mir-BART5 |

NM_014417 |

| CXCL11 |

|

Leukocyte trafficking, target of EBV mir-BHRF1-3 |

NM_005409 |

| CDKN1A |

P21, WAF1 |

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, EBV miR target |

NM_000389.2 |

| FCRL3 |

|

Immune regulation, Fc receptor-like tyrosine kinase |

NM_052939 |

| CD70 |

|

T and NK cell activation, TNF ligand |

NM_001252 |

| FSCN1 |

|

Cell morphology and motility |

NM_003088 |

| TNFSF9 |

|

Antigen (Ag) processing, TNF ligand cytokine |

NM_003811 |

| BCL2L11 |

BIM |

Activator of apoptosis, BCL2-like |

NM_006538 |

| PTEN |

|

Tumor suppressor, EBV miR target |

NM_000314.3 |

| PCNA |

|

DNA replication and repair, cell proliferation indicator |

NM_182649.1 |

| GPR183 |

|

G protein-coupled receptor, EBV-induced |

NM_004951 |

| MX1 |

|

Mediates antiviral response, interferon response |

NM_001144925 |

| IFITM1 |

|

Innate antiviral and interferon response |

NM_003641 |

| FCGR2B |

|

Phagocytosis & antibody production |

NM_004001 |

| ICAM1 |

|

NFKB regulated, cell adhesion |

NM_000201.2 |

| TRAF1 |

|

NFKB regulated, TNF receptor |

NM_005658.3 |

| FCER2 |

CD23 |

NFKB-regulated B cell differentiation, IgE receptor |

NM_002002.4 |

| IL10 |

|

Anti-inflammatory cytokine regulates NFKB signalling |

NM_000572.2 |

|

Hematopoietic cell markers | |||

| PTPRC |

CD45 |

Pan-hematopoietic cell marker, T & B cell signaling |

NM_002838 |

| MS4A1 |

CD20 |

B cell marker, differentiation |

NM_021950 |

| IGLL1 |

CD179B |

B cell marker, growth |

NM_020070 |

| BANK1 |

|

B-cell marker, receptor-induced calcium mobilization |

NM_017935 |

| FAM129C |

|

B cell marker |

NM_173544 |

| MUM1 |

IRF4 |

Late stage B cell, signaling & differentiation |

NM_032853 |

| SDC1 |

CD138 |

Plasma cell, also epithelial cell binding and signaling |

NM_001006946 |

| CD4 |

|

Helper T cells, MHC class II antigen processing |

NM_000616.3 |

| CD8A |

|

Suppressor T cells, MHC class I antigen processing |

NM_001768 |

| CD3G |

-- |

Pan T cell marker, intracellular signaling |

NM_000073 |

| GPR56 |

|

NK cell marker in peripheral tissues |

NG_011643.1 |

|

Pharmacogenetic factors impacting drug response | |||

| ERBB2 |

HER2 |

Kinase-mediated signaling, trastuzumab target |

NM_004448.2 |

| PPARG |

|

Glucose and lipid metabolism |

NM_138711.3 |

| TYMS |

|

Thymidylate synthase, DNA repair, 5FU response |

NM_001071.2 |

| HIF1A |

|

Systemic response to hypoxia |

NM_001530.2 |

| EPAS1 |

|

Angiogenesis |

NM_001430 |

| VEGFA |

|

Mitogen for endothelial cells |

NM_001025366 |

| SLC2A3 |

GLUT3 |

Glucose transporter |

NM_006931.2 |

| SLC2A1 |

GLUT1 |

Glucose transporter |

NM_006516.2 |

|

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) RNAs: |

NC_007605.1 |

||

| LMP1 |

BNLF1 |

TNF/CD40 signalling, latent phase |

3783750 |

| LMP2A |

|

Cell survival , latent phase |

3783751 |

| EBNA1 |

BKRF1 |

Viral persistence, episome, latent phase |

3783709 |

| EBNA1,QUK |

|

Q promoter variant, viral persistence, latent phase |

3783774 |

| EBNA2 |

BYRF1 |

Transactivator, latent phase |

3783761 |

| EBNA3A |

BERF1 |

Immortalization, latent phase |

3783762 |

| EBNA-LP |

|

Transactivator, latent phase |

3783746 |

| EBER1 |

|

Non-coding RNA inhibits apoptosis, latent phase |

AJ507799.2 - 6629.6795 |

| EBER2 |

|

Non-coding RNA inhibits apoptosis, latent phase |

AJ507799.2 - 6956.7128 |

| BZLF1 |

Zta, Zebra |

Immediate early transactivator of lytic replication |

3783744 |

| BMRF1 |

|

Early lytic DNA polymerase processivity factor, TF |

3783718 |

| BHRF1 |

|

Viral BCL2 inhibits apoptosis, early lytic phase |

3783706 |

| BCRF1 |

|

Viral interleukin 10 homologue |

3783689 |

| BARF1 |

|

Soluble CSF1 receptor homologue, early lytic phase |

3783772 |

| BRLF1 |

Rta |

Immediate early transactivator of lytic replication |

3783727 |

| BLLF1 |

gp350/220 |

Viral entry via CD21 receptor, late lytic phase |

3783713 |

| BALF5 |

|

Viral DNA polymerase, early lytic phase |

3783681 |

| BXLF1 |

|

Thymidine kinase, early lytic phase |

3783741 |

|

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) RNAs: |

NC_006273.2 |

||

| UL83 |

pp65 |

Late lytic phase |

3077579 |

| UL54 |

pol |

CMV DNA polymerase, early lytic phase |

3077501 |

|

Housekeeper RNAs | |||

| CLTC |

|

Intracellular trafficking & endocytosis |

NM_004859.2 |

| GUSB |

|

Glucuronidase degrades glycosaminoglycans |

NM_000181.1 |

| TBP |

|

Transcription initiation by TATA box binding protein |

NM_003194.3 |

| HPRT1 | Generation of purine nucleotides | NM_000194.1 | |

Following analysis, raw expression data was first adjusted by subtracting the mean counts of 6 negative controls in the Nanostring reagent system. (Two additional negative controls were omitted because of cross-reactivity with EBERs.) Negative values were adjusted to zero, and then data was normalized for 1) technical variation using the average of 6 positive controls in the Nanostring reagent system as recommended by the manufacturer, and 2) endogenous RNA amount or quality using the average of four housekeeping RNAs (HPRT1, GUSB, CLTC and TBP). To promote accurate profiling, only those 182 specimens with the highest average housekeeping RNA content were used for statistical analysis, while another 140 specimens were excluded based on low average housekeeping RNA levels. The cohort of cases for statistical analysis was comprised of 124 cancers and 58 non-malignant mucosae, while cohort of cases excluded from statistical analysis because of poor RNA quality was comprised of 80 cancers and 60 non-malignant mucosae. Heat maps were created to show median-centered expression of each gene using Cluster 3.0 and JavaTreeView software algorithms applied to log2 transformed data.

EBV Q-PCR and EBER in situ hybridization

To measure viral DNA load, an aliquot of the same total nucleic acid extract that had been used for RNA profiling was subjected to quantitative PCR targeting the BamH1W segment of the EBV genome [94]. A parallel Q-PCR assay targeting the human APOB gene controlled for efficacy of DNA extraction was used to normalize for the number of cells represented in the PCR assay as previously described [94]. Amplification products were measured on an ABI Prism 7500 Real-Time PCR instrument using TaqMan probe and Sequence Detection System software (Applied Biosystems) [82], and results reported in copies of EBV DNA per 100,000 cells.

Viral localization to malignant cells was tested using EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization on paraffin sections (BOND assay, Leica Microsystems) [95]. As a quality control, RNA preservation was confirmed in parallel in situ hybridization to poly A tails by oligo-dT probe.

Statistics

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of gastric cancer tissues revealed the EBV-infected and uninfected molecular classes of gastric cancer. Three additional tissue classes (cervical cancer, and benign gastrointestinal or cervical mucosae) were defined by clinicopathologic criteria. In box plots, the median and middle two quartiles are surrounded by whiskers depicting outliers which are far above or below the interquartile range (IQR) by > Q3 + 1.5*IQR or < Q1-1.5*IQR, respectively. Genes significantly differentially expressed among groups were identified using non parametric Mann-Whitney tests and the p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. A given RNA was classified as significantly differentially expressed if its Bonferroni adjusted p value was <0.05 and it was more differentially expressed than any single one of the four housekeeping RNAs.

Abbreviations

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; NU: Normalized unit.

Competing interests

MLG is a consultant for McKesson, Abbott Laboratories, and Roche Molecular Systems and serves on the clinical advisory board of Generation Health.

Authors' contributions

WT and HM designed and implemented experiments and analyzed data. DRM, MOM, RLD EM, KK, and NB defined clinical priorities and provided annotated case material. PFK performed statistical analysis and prepared figures. KW and OS performed histopathologic assessment of malignant cell proportions. MLG designed the assay, interpreted data, and finalized the manuscript. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Weihua Tang, Email: weihua_tang@med.unc.edu.

Douglas R Morgan, Email: Douglas_Morgan@med.unc.edu.

Michael O Meyers, Email: michael_meyers@med.unc.edu.

Ricardo L Dominguez, Email: ricardoleoneldominguez@yahoo.com.

Enrique Martinez, Email: vanor77@yahoo.com.

Kennichi Kakudo, Email: k16kakudo@carol.ocn.ne.jp.

Pei Fen Kuan, Email: pfkuan@email.unc.edu.

Natalie Banet, Email: nbanet@unch.unc.edu.

Hind Muallem, Email: muallem@email.unc.edu.

Kimberly Woodward, Email: kwoodward@unch.unc.edu.

Olga Speck, Email: OSpeck@unch.unc.edu.

Margaret L Gulley, Email: margaret_gulley@med.unc.edu.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joel Parker, PhD for advice on data analysis, Takashi Ozaki, MD of Kinan General Hospital for providing tissues, and Marc Salit, PhD of the National Institute of Standards and Technology for providing RNA from the External RNA Controls Consortium. This study was sponsored by the University of North Carolina Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the Environmental Pathology Training Grant (NIH T32-ES07017) funding graduate studies of Hind Muallem, PhD, the University Cancer Research Fund, the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (NCI U10 CA031946), a Clinical Translational Science Award (NIH U54 RR024383), an award for Innovative Technologies for Molecular Analysis of Cancer (NCI R21 CA155543), an Award (NCI CA125588) supporting Douglas Morgan, MD MPH, and the UNC Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease (NIH P30 DK 034987).

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Kim JY, Yoo J, Lee SS. Gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma: incidence of EBV and Helicobacter pylori infection. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2003;11:149–152. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200306000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WY, Liu Y, Li CY, Ng EK, Chow JH, Li KK, Chung SC. Recurrent genomic aberrations in gastric carcinomas associated with Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2002;11:127–134. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A, Nath Prasad K, Chand Ghoshal U, Krishnani N, Roshan Bhagat M, Husain N. Association of Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus with gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:669–674. doi: 10.1080/00365520801909660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kim SH, Han SH, An JS, Lee ES, Kim YS. Clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:354–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WF, Camargo MC, Fraumeni JF, Correa P, Rosenberg PS, Rabkin CS. Age-specific trends in incidence of noncardia gastric cancer in US adults. JAMA. 2010;303:1723–1728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo MC, Anderson WF, King JB, Correa P, Thomas CC, Rosenberg PS, Eheman CR, Rabkin CS. Divergent trends for gastric cancer incidence by anatomical subsite in US adults. Gut. 2011;60:1644–1649. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.236737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriyama C, Akiba S, Corvalan A, Carrascal E, Itoh T, Herrera-Goepfert R, Eizuru Y, Tokunaga M. Histology-specific gender, age and tumor-location distributions of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma in Japan. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:543–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Chang MS, Yang HK, Lee BL, Kim WH. Epstein-barr virus-positive gastric carcinoma has a distinct protein expression profile in comparison with epstein-barr virus-negative carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1698–1705. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek J, zur Hausen A, Klein Kranenbarg E, van de Velde CJ, Middeldorp JM, van den Brule AJ, Meijer CJ, Bloemena E. EBV-positive gastric adenocarcinomas: a distinct clinicopathologic entity with a low frequency of lymph node involvement. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:664–670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda K, Tamaru J, Takenouchi T, Mikata A, Nunomura M, Saitoh N, Sarashina H, Nakajima N. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1063–1071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MS, Shun CT, Wu CC, Hsu TY, Lin MT, Chang MC, Wang HP, Lin JT. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinomas: relation to H. pylori infection and genetic alterations. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BG, Gulley ML, Eagan P, Bravo JC, Mera R, Geradts J. Loss of p16/CDKN2A tumor suppressor protein in gastric adenocarcinoma is associated with Epstein-Barr virus and anatomic location in the body of the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(00)80197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo MC, Murphy G, Koriyama C, Pfeiffer RM, Kim WH, Herrera-Goepfert R, Corvalan AH, Carrascal E, Abdirad A, Anwar M. et al. Determinants of Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer: an international pooled analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:38–43. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravalos C, Gomez-Martin C, Rivera F, Ales I, Queralt B, Marquez A, Jimenez U, Alonso V, Garcia-Carbonero R, Sastre J. et al. Phase II study of trastuzumab and cisplatin as first-line therapy in patients with HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah MA, Kelsen DP. Gastric cancer: a primer on the epidemiology and biology of the disease and an overview of the medical management of advanced disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:437–447. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos JC, Lossos IS. Newly emerging therapies targeting viral-related lymphomas. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13:416–426. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HJ, Srivastava A, Lee J, Kim YS, Kim KM, Ki Kang W, Kim M, Kim S, Park CK. Host inflammatory response predicts survival of patients with Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:84–92. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo A, Turrini R, Dolcetti R, Zanovello P, Rosato A. Immunotherapy for EBV-associated malignancies. Int J Hematol. 2011;93:281–293. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0782-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis CU, Straathof K, Bollard CM, Ennamuri S, Gerken C, Lopez TT, Huls MH, Sheehan A, Wu MF, Liu H. et al. Adoptive transfer of EBV-specific T cells results in sustained clinical responses in patients with locoregional nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:983–990. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181f3cbf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Lim J, Kang JS, Kim HM, Lee HK, Ryu HS, Kim JY, Hong JT, Kim Y, Han SB. Adoptive immunotherapy of human gastric cancer with ex vivo expanded T cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1789–1795. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-1111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist A, Berg M, Smith A, Childs RW. Bortezomib Treatment to Potentiate the Anti-tumor Immunity of Ex-vivo Expanded Adoptively Infused Autologous Natural Killer Cells. J Cancer. 2011;2:383–385. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukayama M, Ushiku T. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claerhout S, Lim JY, Choi W, Park YY, Kim K, Kim SB, Lee JS, Mills GB, Cho JY. Gene expression signature analysis identifies vorinostat as a candidate therapy for gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle D, Megyola C, El-Guindy A, Gradoville L, Tuck D, Miller G, Bhaduri-McIntosh S. Upregulation of STAT3 marks Burkitt lymphoma cells refractory to Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle induction by HDAC inhibitors. J Virol. 2010;84:993–1004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01745-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destro F, Sforza F, Sicurella M, Marescotti D, Gallerani E, Baldisserotto A, Marastoni M, Gavioli R. Proteasome inhibitors induce the presentation of an Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1-derived cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Immunology. 2011;133:105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley CM, Chen J, Shamay M, Li H, Zahnow CA, Hayward SD, Ambinder RF. Bortezomib induction of C/EBPbeta mediates Epstein-Barr virus lytic activation in Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:6297–6303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney S. Theodore E. Woodward Award: Development of Novel, EBV-Targeted Therapies for EBV-Positive Tumors. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2006;117:55–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzmann F, Jager M, Prang N, Wolf H. The control of lytic replication of Epstein-Barr virus in B lymphocytes (Review) Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:137–142. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laichalk LL, Thorley-Lawson DA. Terminal differentiation into plasma cells initiates the replicative cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79:1296–1307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1296-1307.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WH, Kenney SC. Valproic acid enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy in EBV-positive tumors by increasing lytic viral gene expression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8762–8769. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KF, Chiang AK. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid induces viral lytic cycle in Epstein-Barr virus-positive epithelial malignancies and mediates enhanced cell death. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2479–2489. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WH, Israel B, Raab-Traub N, Busson P, Kenney SC. Chemotherapy induces lytic EBV replication and confers ganciclovir susceptibility to EBV-positive epithelial cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1920–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WH, Westphal E, Mauser A, Raab-Traub N, Gulley ML, Busson P, Kenney SC. Use of adenovirus vectors expressing Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) immediate-early protein BZLF1 or BRLF1 to treat EBV-positive tumors. J Virol. 2002;76:10951–10959. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10951-10959.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WH, Cohen JI, Fischer S, Li L, Sneller M, Goldbach-Mansky R, Raab-Traub N, Delecluse HJ, Kenney SC. Reactivation of latent Epstein-Barr virus by methotrexate: a potential contributor to methotrexate-associated lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1691–1702. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng WH, Hong G, Delecluse HJ, Kenney SC. Lytic induction therapy for Epstein-Barr virus-positive B-cell lymphomas. J Virol. 2004;78:1893–1902. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1893-1902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, Nourse J, Corbett G, Gandhi MK. Sodium valproate in combination with ganciclovir induces lysis of EBV-infected lymphoma cells without impairing EBV-specific T-cell immunity. Int J Lab Hematol. 2010;32:e169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2008.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal EM, Blackstock W, Feng W, Israel B, Kenney SC. Activation of lytic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection by radiation and sodium butyrate in vitro and in vivo: a potential method for treating EBV-positive malignancies. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5781–5788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Jin H, Cheung KF, Tong JH, Zhang S, Go MY, Tian L, Kang W, Leung PP, Zeng Z. et al. Zinc finger E-box binding factor 1 plays a central role in regulating Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent-lytic switch and acts as a therapeutic target in EBV-associated gastric cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:924–936. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q, Hagemeier SR, Fingeroth JD, Gershburg E, Pagano JS, Kenney SC. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded protein kinase, EBV-PK, but not the thymidine kinase (EBV-TK), is required for ganciclovir and acyclovir inhibition of lytic viral production. J Virol. 2010;84:4534–4542. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02487-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Hu Z, Muallem H, Gulley ML. Quality assurance of RNA expression profiling in clinical laboratories. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis PP, Waldron L, Goswami RS, Xu W, Xuan Y, Perez-Ordonez B, Gullane P, Irish J, Jurisica I, Kamel-Reid S. mRNA transcript quantification in archival samples using multiplexed, color-coded probes. BMC Biotechnol. 2011;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkov VA, Serikawa KA, Balantac N, Watters J, Geiss G, Mashadi-Hossein A, Fare T. Multiplexed measurements of gene signatures in different analytes using the Nanostring nCounter Assay System. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:80. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni MM. Digital multiplexed gene expression analysis using the NanoString nCounter system. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2011. Chapter 25: Unit 25B 10. [ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/0471142727.mb25b10s94/abstract] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ryan JL, Morgan DR, Dominguez RL, Thorne LB, Elmore SH, Mino-Kenudson M, Lauwers GY, Booker JK, Gulley ML. High levels of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in latently infected gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 2009;89:80–90. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyde K, Glaunsinger BA. Deep sequencing reveals direct targets of gammaherpesvirus-induced mRNA decay and suggests that multiple mechanisms govern cellular transcript escape. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, Koizumi S, Sugiura M, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Yamamoto N, Tanaka S, Sato E, Osato T. Gastric carcinoma: monoclonal epithelial malignant cells expressing Epstein-Barr virus latent infection protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9131–9135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M, Imai S, Tokunaga M, Koizumi S, Uchizawa M, Okamoto K, Osato T. Transcriptional analysis of Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in EBV-positive gastric carcinoma: unique viral latency in the tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:625–631. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, Wang Y, Wang XF, Liang H, Yan LP, Huang BH, Zhao P. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus genes in EBV-associated gastric carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:629–633. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen A, Brink AA, Craanen ME, Middeldorp JM, Meijer CJ, van den Brule AJ. Unique transcription pattern of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in EBV-carrying gastric adenocarcinomas: expression of the transforming BARF1 gene. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2745–2748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeung HC, Rha SY, Im CK, Shin SJ, Ahn JB, Yang WI, Roh JK, Noh SH, Chung HC. A randomized phase 2 study of docetaxel and S-1 versus docetaxel and cisplatin in advanced gastric cancer with an evaluation of SPARC expression for personalized therapy. Cancer. 2011;117:2050–2057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YB, Chung HJ, Lee WY, Choi SH, Kim HC, Yun SH, Chun HK. Relationship between TYMS and ERCC1 mRNA expression and in vitro chemosensitivity in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3843–3849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SM, Cannon JS, Tanhehco YC, Hamzeh FM, Ambinder RF. Induction of Epstein-Barr virus kinases to sensitize tumor cells to nucleoside analogues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2082–2091. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2082-2091.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui W, Oue N, Sentani K, Sakamoto N, Motoshita J. Transcriptome dissection of gastric cancer: identification of novel diagnostic and therapeutic targets from pathology specimens. Pathol Int. 2009;59:121–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentani K, Oue N, Sakamoto N, Arihiro K, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Yasui W. Gene expression profiling with microarray and SAGE identifies PLUNC as a marker for hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:464–475. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zeng Z, Zhang W, Xiong W, Li X, Zhang B, Yi W, Xiao L, Wu M, Shen S. et al. Identification of candidate molecular markers of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by microarray analysis of subtracted cDNA libraries constructed by suppression subtractive hybridization. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:561–571. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328305a0e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reka AK, Goswami MT, Krishnapuram R, Standiford TJ, Keshamouni VG. Molecular cross-regulation between PPAR-gamma and other signaling pathways: implications for lung cancer therapy. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki A, Ushiku T, Morikawa T, Hino R, Sakatani T, Uozaki H, Fukayama M. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma: a distinct carcinoma of gastric phenotype by claudin expression profiling. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:775–785. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh HK, Tan AL, Das K, Ooi CH, Deng NT, Tan IB, Beillard E, Lee J, Ramnarayanan K, Rha SY. et al. Genomic Loss of miR-486 Regulates Tumor Progression and the OLFM4 Antiapoptotic Factor in Gastric Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2657–2667. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhao ZW, Zhang Y, Xin Y. Over-expression of Ephb4 is associated with carcinogenesis of gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:698–706. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan IB, Ivanova T, Lim KH, Ong CW, Deng N, Lee J, Tan SH, Wu J, Lee MH, Ooi CH. et al. Intrinsic subtypes of gastric cancer, based on gene expression pattern, predict survival and respond differently to chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:476–485. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.042. 485 e471-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon JH, Fujiwara Y, Nakamura Y, Okada K, Hanada H, Sakakura C, Takiguchi S, Nakajima K, Miyata H, Yamasaki M. et al. REGIV as a potential biomarker for peritoneal dissemination in gastric adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:189–194. doi: 10.1002/jso.22021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca C, Macchi RM, Marschner AK, Mellstedt H. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule expression (CD326) in cancer: a short review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins GT, Nie D. PPAR gamma, bioactive lipids, and cancer progression. Front Biosci. 2012;17:1816–1834. doi: 10.2741/4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani Y, Oue N, Matsumura S, Yoshida K, Noguchi T, Ito M, Tanaka S, Kuniyasu H, Kamata N, Yasui W. Reg IV is a serum biomarker for gastric cancer patients and predicts response to 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2007;26:4383–4393. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EY, Siu KL, Kok KH, Lung RW, Tsang CM, To KF, Kwong DL, Tsao SW, Jin DY. An Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA targets PUMA to promote host cell survival. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2551–2560. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieging KT, Fish K, Bondada S, Longnecker R. A shared gene expression signature in mouse models of EBV-associated and non-EBV-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:6849–6859. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai H, Brown RE. Field effect in cancer-an update. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2009;39:331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes DG, Shair KH, Marquitz AR, Kung CP, Edwards RH, Raab-Traub N. Human tumor virus utilizes exosomes for intercellular communication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20370–20375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014194107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckes DG, Raab-Traub N. Microvesicles and viral infection. J Virol. 2011;85:12844–12854. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05853-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Chen Y, Chou WC, Sun L, Chen L, Suo J, Ni Z, Zhang M, Kong X, Hoffman LL. et al. An integrated transcriptomic and computational analysis for biomarker identification in gastric cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1197–1207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Kim J, Korolevich S, Choi IJ, Kim CH, Munroe DJ, Green JE. Distinctions in gastric cancer gene expression signatures derived from laser capture microdissection versus histologic macrodissection. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:48. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yang JJ, Kim YS, Kim KY, Ahn WS, Yang S. An 8-gene signature, including methylated and down-regulated glutathione peroxidase 3, of gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:405–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Cui J, Olman V, Yang Q, Puett D, Xu Y. A comparative analysis of gene-expression data of multiple cancer types. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junnila S, Kokkola A, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Puolakkainen P, Monni O. Genome-wide gene copy number and expression analysis of primary gastric tumors and gastric cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E, Suzuki H, Takamaru H, Yamamoto H, Toyota M, Shinomura Y. Role of DNA methylation in the development of diffuse-type gastric cancer. Digestion. 2011;83:241–249. doi: 10.1159/000320453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald RC, Hardwick R, Huntsman D, Carneiro F, Guilford P, Blair V, Chung DC, Norton J, Ragunath K, Van Krieken JH. et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet. 2010;47:436–444. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.074237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niller HH, Wolf H, Minarovits J. Epigenetic dysregulation of the host cell genome in Epstein-Barr virus-associated neoplasia. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osato T, Imai S. Epstein-Barr virus and gastric carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 1996;7:175–182. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1996.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida Y, Miyauchi K, Takano Y. Gastric adenocarcinoma with differentiation to sarcomatous components associated with monoclonal Epstein-Barr virus infection and LMP-1 expression. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1993;423:383–387. doi: 10.1007/BF01607151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JL, Shen YJ, Morgan DR, Thorne LB, Kenney SC, Dominguez RL, Gulley ML. Epstein-Barr Virus Infection Is Common in Inflamed Gastrointestinal Mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shinkura R, Yamamoto N, Koriyama C, Shinmura Y, Eizuru Y, Tokunaga M. Epstein-Barr virus-specific antibodies in Epstein-Barr virus-positive and -negative gastric carcinoma cases in Japan. J Med Virol. 2000;60:411–416. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(200004)60:4<411::AID-JMV8>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Kobayashi R, Horiuchi M, Nagata Y, Hasegawa M, Mizuno F, Hirai K. Detection of lymphocytes productively infected with Epstein-Barr virus in non-neoplastic tonsils. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1211–1216. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-5-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JL, Jones RJ, Kenney SC, Rivenbark AG, Tang W, Knight ER, Coleman WB, Gulley ML. Epstein-Barr virus-specific methylation of human genes in gastric cancer cells. Infect Agent Cancer. 2010;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WY, Twu CW, Chen HH, Jan JS, Jiang RS, Chao JY, Liang KL, Chen KW, Wu CT, Lin JC. Plasma EBV DNA clearance rate as a novel prognostic marker for metastatic/recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1016–1024. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Fang Z, Liu L, Yang S, Zhang L. Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus DNA in Serum or Plasma for Nasopharyngeal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;45:1292–1294. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley ML, Tang W. Using Epstein-Barr viral load assays to diagnose, monitor, and prevent posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:350–366. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo KW, Lo YM, Leung SF, Tsang YS, Chan LY, Johnson PJ, Hjelm NM, Lee JC, Huang DP. Analysis of cell-free Epstein-Barr virus associated RNA in the plasma of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1292–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso S, Zecca M, Merli P, Gurrado A, Secondino S, Quartuccio G, Guido I, Guerini P, Ottonello G, Zavras N. et al. T cell therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cancer. 2011;2:341–346. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sili U, Leen AM, Vera JF, Gee AP, Huls H, Heslop HE, Bollard CM, Rooney CM. Production of good manufacturing practice-grade cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and adenovirus to prevent or treat viral infections post-allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:7–11. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.636963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S, Saito T, Ito Y, Kamakura M, Gotoh K, Kawada J, Nishiyama Y, Kimura H. Antitumor activities of valproic acid on Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and natural killer lymphoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh SK, Perrine SP, Faller DV. Advances in Virus-Directed Therapeutics against Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Malignancies. Adv Virol. 2012;2012:509296. doi: 10.1155/2012/509296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JL, Fan H, Glaser SL, Schichman SA, Raab-Traub N, Gulley ML. Epstein-Barr virus quantitation by real-time PCR targeting multiple gene segments: a novel approach to screen for the virus in paraffin-embedded tissue and plasma. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:378–385. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60535-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DY, Qian J, Easley KA, Waldrop SM, Cohen C. Automated in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry for cytomegalovirus detection in paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17:158–164. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e318185d1b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]