Abstract

Spouses often seek to influence the health behaviors of chronically ill partners, but little research has examined whether spouses find such involvement to be burdensome. The current study examined this question in a sample of 191 nondiabetic spouses whose partners had type 2 diabetes. Results revealed that spouses who attempted to exert more control over their partners’ dietary behavior experienced greater burden, particularly when their partners exhibited poor dietary adherence and reacted negatively to spouses’ involvement. The findings contribute to a sparse body of knowledge on how spouses are affected by efforts to influence their chronically ill partners’ disease management.

Keywords: marriage, social control, chronic illness, type 2 diabetes, burden

Spouses are frequently involved in their partners’ chronic health conditions (Ell, 1996), often by seeking to promote greater adherence to medical regimens. Diabetes is both an increasingly common chronic condition and one that requires adherence to a complex medical regimen, with dietary changes as a key component (American Diabetes Association, 2010). Because these dietary changes require patients’ continual attention to food choices on a daily basis, nonadherence is common (McNabb, 1997). Spouses are uniquely positioned to notice such nonadherence, and as such, often are directly involved in monitoring and influencing many of their partners’ disease-related health behavior changes (Trief et al., 2003). Thus, spouses often seek to induce greater adherence by serving as sources of health-related social control. Health-related social control refers to network members’ attempts to monitor and influence health behaviors by encouraging health-enhancing behaviors and discouraging health-compromising behaviors (Lewis & Rook, 1999). In studies of general community samples, spouses have been found to be the most common sources of health-related social control (Tucker, 2002; Umberson, 1992).

Social control has been highlighted in the broader literature on social relationships and health as a potential pathway by which social networks can influence health (e.g., Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000). Social control theory posits that when individuals are unable to self-regulate their own health behaviors, their social network members mobilize to discourage health-compromising behaviors (Rook, 1990; Umberson, 1987). Family members and friends who attempt to exert social control thus typically do so with the intention to promote better health behaviors in the recipients of such attempts (Lewis & Butterfield, 2005; Tucker & Anders, 2001). These influence attempts may not be well received by recipients, however, who may resent the supervision and constraints placed on their behavior (Rook, Thuras, & Lewis, 1990). Recipients may resist social control attempts by hiding unhealthy behaviors, ignoring the network members’ requests, or deliberately increasing unhealthy behaviors (Tucker, 2002). Recipients also may experience psychological distress in response to social control attempts if they feel that their autonomy and sense of efficacy are being undermined (Lewis & Rook, 1999; Tucker, 2002). Adverse reactions to social control have been documented in previous studies (e.g., Tucker & Anders, 2001), although other studies suggest that recipients sometimes appreciate network members’ involvement in their health (e.g., Rook & Ituarte, 1999). To date, the literature on social control has focused mainly on how the recipient responds behaviorally or affectively and how these responses ultimately affect the recipient’s health. These responses may, in turn, be associated with consequences for agents of social control.

Little is known, however, about the correlates of engaging in social control. In the context of a chronic illness in which network members, such as spouses, help manage the daily tasks associated with their partner’s illness, consequences of engaging in social control attempts may be especially pronounced. Because diabetes management, in particular, requires adherence to daily tasks that often occur in the home (Fisher et al., 1998), spouses are uniquely positioned to experience potential burden from seeking to influence their partners’ dietary behaviors. The current study thus sought to examine the potential consequences for spouses seeking to exert health-related social control on a marital partner with type 2 diabetes.

Association between Exerting Health-Related Social Control and Spouse Burden

Although exerting social control is a uniquely different experience than caregiving, insights about how spouses may be affected by their involvement in their ill partners’ health can be derived by extrapolating from the literature on caregiver burden. Research on caregiving suggests that providing care to an ill family member may lead to feelings of burden as a result of the chronic stress it elicits (Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlan, 2003). By analogy, spouses may experience burden from exerting social control because they may perceive too much responsibility for their partners’ treatment adherence – for example, having to induce their partners to adhere to their diet. This burden may stem from the time and effort spouses devote to helping their partners, as well as from potential adverse effects on their psychological or physical health (see Coyne & Smith, 1994). For example, although not designed as a study of social control, one study of couples managing type 2 diabetes found that despite their efforts to stay uninvolved, spouses often became involved at their diabetic partners’ insistence. As a result of their unwanted involvement, many spouses in this study reported feeling burdened by having to keep their diabetic partners on track with their diet (Miller & Brown, 2005).

Spouses’ feelings of burden also could stem from the disruption of their own routines or the drains on their energy from having to monitor and seek to influence their partners’ health behaviors on a daily basis (see Sales, 2003). Evidence for these ideas emerged in a focus group study of couples managing type 2 diabetes, in which spouses expressed distress/resentments about changes in their routines and drains on their energy associated with having to deal with the dietary aspects of their partners’ condition (Beverly, Penrod, & Wray, 2007). Such work underscores the importance of examining the psychological correlates of spouses’ efforts to be involved in their partners’ disease management.

Factors Influencing the Association between Exerting Social Control and Spouse Burden

Not all spouses are likely to experience burden, however, as a result of being involved in their partner’s illness management. How patients respond emotionally and behaviorally to their spouses’ use of social control may play a role in determining whether spouses experience burden from engaging in health-related social control. Moreover, how well patients are managing their diet may influence the extent to which their reactions to social control contribute to spouse burden.

Patients’ responses to spousal social control

Theory and research on caregiving provide a basis for making the prediction that burden associated with engaging in social control may depend on patients’ reactions to social control. If patients react negatively to their spouses’ social control attempts – for example by expressing hostility, or by engaging in worse, rather than better, dietary behavior – their spouses may consider their efforts to have been wasted or rebuked, which could lead to feelings of burden. Patients may react to social control attempts with hostility because they resent spouses’ intrusion in their health or because spouses may unintentionally (or intentionally) convey a sense of disappointment at having to be involved in the patients’ health. Thus, spouses whose partners respond to social control with hostility may feel more burdened.

Support for this idea emerged in a study that examined emotional and physical health in caregivers of elder relatives (Koerner & Kenyon, 2007). Greater caregiving stressors, such as dealing with care recipients’ anger, were especially predictive of feelings of burden and depressive symptoms among the caregivers. Patients sometimes also rebuff their spouses’ involvement in their health, as documented in a study of women with osteoarthritis who engaged in worse self-care behaviors when they received unwanted advice from their spouses (Martire, Stephens, Druley, & Wojno, 2002). Patients with diabetes, too, have reported engaging in behavioral resistance, such as hiding their poor food choices (Miller & Brown, 2005). Such behavioral resistance could lead spouses to experience anger or frustration. On the other hand, if patients react positively to spousal social control – for example, by expressing appreciation – their spouses may not experience burden because they are likely to regard the energy and time invested in helping their partners as worthwhile.

Patients’ dietary adherence

If patients are adhering poorly to their medical regimen, and are also reacting negatively to spousal efforts to promote greater adherence, spouses may be especially likely to experience feelings of burden. Evidence for this possibility can be found in studies of spousal social support in the context of a chronic illness. For example, in a study of couples managing diabetes together, when spouses provided support for their partners’ dietary changes, their partners’ nonadherence resulted in tension or conflict in the relationship (Trief et al., 2003). Similarly, spouses who engage in social control attempts but whose partners exhibit poor dietary adherence may feel that their efforts have failed or been wasted or that they will have to intensify their efforts in the future to promote adherence. As a result of this perception of failure or obligations for continued involvement, spouses may feel a sense of burden. If, on the other hand, patients are adhering well to their own medical regimen, spouses might not experience burden even if the patients were not reacting favorably to their involvement. For this reason, patients’ negative reactions to their spouses’ social control attempts may be most likely to account for spouse burden when patients are nonadherent. Seeing patients adhere well, in contrast, may provide its own rewards for being involved in the patients’ health, thereby buffering spouses to some extent from feeling distressed or burdened by patients’ negative reactions to their involvement.

The Current Study

Little attention has focused on the potential effects of engaging in social control, particularly in the context of a partner’s chronic illness. The current study sought to address this gap in knowledge by investigating whether spouses who exert more health-related social control to a marital partner with type 2 diabetes experience more feelings of burden. The current study also sought to determine whether patients’ reactions to spousal social control help to explain spouses’ feelings of burden and whether the mediating role of patients’ reactions depends upon patients’ level of dietary adherence.

Our hypotheses are guided by the integration of theoretical perspectives on social control (Rook, 1990; Umberson, 1987) and caregiving (see review by Vitaliano et al., 2003). Specifically, we hypothesized that spousal engagement in more social control would be associated with greater burden. We further hypothesized that patients’ negative reactions to spousal social control (behavioral resistance, hostility, lack of appreciation) would contribute to spouses’ feelings of burden and that the mediating role of patients’ negative reactions would be most evident when patients were adhering poorly to their diabetic diet. The latter hypothesis involves a joint prediction about mediation and the specific context in which mediation would be likely to occur and, therefore, will be examined using an analytic approach that accounts for mediation and moderation simultaneously (moderated mediation regression analysis).

Method

Participants and Procedures

The sample for the current study consisted of 191 nondiabetic spouses whose martial partners were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. A majority (62.8%) of nondiabetic spouses in the current study were female with a mean age of 66.47 years (SD = 8.68). Most (94.9%) spouses had at least a high-school education, and majorities (65.4%) of spouses were retired; 17.8% worked full-time, 8.4% worked part-time, and 8.4% were homemakers or not otherwise employed. Most (95.8%) spouses were non-Hispanic white; 4.2% of spouses were African American/black or Hispanic. Couples reported being married 39.36 years (SD = 13.53), on average.

Data were derived from a larger study of couples managing type 2 diabetes that had university Institutional Review Board approval. Couples were recruited through newspaper advertisements, senior citizen center presentations, online advertisements, and flyers posted in a diabetes education center. Eligibility criteria for patients included having a medically-confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, being aged 50 years or older, and being married or in a marital-like relationship with a nondiabetic spouse. Once eligibility was verified and the patient consented to participation, the patient’s spouse was contacted and consented. Both members of the couple received questionnaires to complete independently. Each member of the couple received $10 upon receipt of completed questionnaires. The current study focused on spouse reports only because it was expected that spouses’ own views of their social control efforts and their partners’ reactions would be most consequential for their well-being and that spouse views adequately reflect the occurrence of social control in a marital relationship (e.g., Franks, Wendorf, Gonzalez, & Ketterer, 2004).

Measures

Social control

Items similar to those from other studies were used to assess social control (e.g., Stephens, Fekete, Franks, Rook, Druley, & Greene, 2009). Spouses rated the frequency with which they used social control strategies to influence their partners’ dietary choices on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 4 = very often/at least one time a day). The items asked spouses “How often, in the past month, have you tried to warn your husband/wife about the consequences of eating an unhealthy diet?” and “How often in the past month have you tried to restrict your husband’s/wife’s diet?” The two items were strongly correlated (r = .58, p < .01) and accordingly were averaged to create a composite measure of social control.

Spouse burden

Six items from a spouse version of the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) scale (Welch, Jacobson, & Polonsky, 1997) were used to assess spouse burden. Spouses rated the extent to which certain problems related to their marital partners’ diabetes were currently a problem for them on a 6-point scale (0 = no problem, 5 = serious problem). Sample items included being burned out, too much energy taken up by patient’s diabetes, and feeling overwhelmed by having to monitor patient’s diabetes. Items were averaged to create a composite measure of spouse burden (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Patients’ behavioral resistance

To assess spousal perceptions of patients’ behavioral resistance, items were adapted from Tucker and Anders (2001). Spouses rated on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all, 6 = very much) how they thought their partners responded behaviorally to each strategy. The items included: 1) [patient] did the opposite of what the spouse was asking, 2) [patient] ignored the spouse’s request, 3) [patient] hid behavior from the spouse, and 4) [patient] went along with the spouse’s request (reverse scored). Items were averaged to create a composite measure of behavioral resistance to spousal control (Cronbach’s α = .79).

Patients’ emotional responses

To assess spousal perceptions of their partners’ emotional responses to social control attempts, 10 items were adapted from Lewis and Rook (1999). Spouses rated on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all, 6 = very much) how they thought their partners responded emotionally to each social control strategy. Four items were averaged to assess hostile emotional responses to each strategy, reflecting how resentful/bitter and irritated/angry the spouse thought the patient felt in response to the spouse’s social control efforts (Cronbach’s α =.92). In addition, six items were averaged to assess appreciative emotional responses to each strategy, reflecting how loved/cared for, how appreciative/grateful, and how hopeful/optimistic the patient felt in response to the spouse’s social control efforts (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Patients’ dietary adherence

To assess spousal perceptions of patients’ dietary adherence, spouses responded to three items that assessed the extent to which the patients followed their recommended diet. A sample item included “Avoided unhealthy foods that interfered with his/her diabetes management.” Spouses rated on a 4-point scale the extent of their partners’ adherence (0 = not at all, 3 = very much). Items were averaged to create a composite score (Cronbach’s α = .86). For moderated mediation regression analyses, we dichotomized the variable at the median to represent low (0 = not a lot to somewhat) and high (1 = very much) patient adherence.

Covariates

A number of variables that either have been included in previous research on social relationships and health and/or exhibited a significant correlation with one of the key study variables were included in the analyses as covariates. These included standard demographic characteristics, such as gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and age. In addition, spouses’ self-rated health, depressive symptomatology using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (Radloff, 1977; Cronbach’s α =.79), time since patient diagnosis, and marital quality using the Quality Marriage Index (Norton, 1983; Cronbach’s α = .98) were included as covariates.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for the key study variables. Correlational analyses revealed that greater spousal engagement in social control was significantly associated with more spouse burden, more patient behavioral resistance and hostility, and lower patient adherence.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for key study variables (N = 191)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Spousal social control | 1.33 | 1.05 | ____ | .27*** | .21** | .18* | .03 | −.22** |

| 2. Spouse burden | .89 | 1.10 | ____ | .34*** | .40*** | −.14 | −.24** | |

| 3. Patient behavioral resistance | 2.45 | .93 | ____ | .61*** | −.60*** | −.43*** | ||

| 4. Patient hostility | 2.22 | 1.33 | ____ | −.48*** | −.22** | |||

| 5. Patient appreciation | 3.61 | 1.32 | ____ | .33*** | ||||

| 6. Patient adherence | 2.13 | .74 | ____ |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Thirty-four spouses did not report exerting any spousal control, so these participants were excluded from regression analyses examining spouse burden as a function of patients’ reactions to social control and level of adherence. T-test analyses indicated that spouses who did not report exerting any social control were more likely to be male (t (189) = −2.93, p < .01) and to have more adherent partners (t(189) = 2.72, p < .01), compared to spouses who reported exerting social control. The two groups did not differ significantly with regard to spouse burden, age, education level, work status, self-rated health, depressive symptomatology, marital quality, and time since patient diagnosis.

Was Spousal Social Control Associated with Spouse Burden

Our first analysis examined whether spouses who engaged in more social control would experience greater burden. In hierarchical linear regression analyses, covariates (spouse gender, age, self-rated health, depressive symptomatology, marital quality, and time since patient diagnosis) were entered in step 1 and social control was entered in step 2 in a model with spouse burden as the outcome. The results revealed that more frequent social control was significantly associated with more spouse burden (β = .28, p <.001).

To determine the potential contribution of patient reports, analyses also were conducted with patient reports of social control included in the model. Because the results remained the same and revealed no additional contribution of patient reports beyond spouse reports, subsequent analyses examined spouse reports only.

Do Patients’ Reactions Mediate, and Patients’ Adherence Moderate, the Association between Spousal Control and Burden?

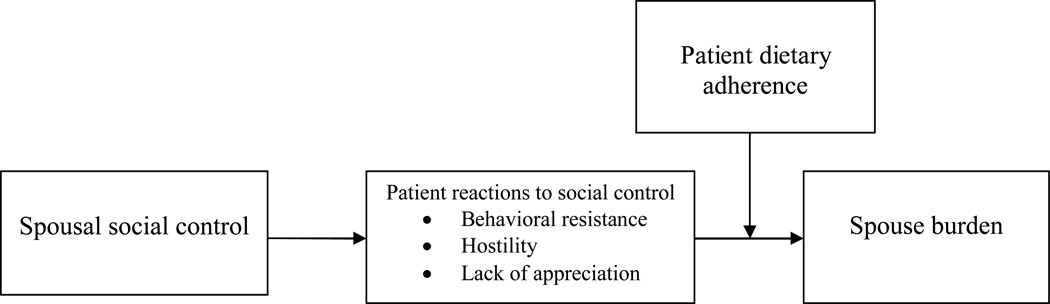

Our next set of analyses used moderated mediation regression analysis (cf. Rees & Freedman, 2009) to examine whether behavioral and emotional reactions to social control mediated the association between spousal engagement in social control and spouse burden and whether this mediation was stronger or weaker for different levels of patient adherence (i.e., whether mediation was moderated by patient adherence). Moderated mediation is the appropriate statistical approach when a mediating process that accounts for the effect of the independent variable on the outcome is expected to differ in terms of strength and/or direction across levels of a moderator variable (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). Thus, moderated mediation analysis captures the specific conditions in which indirect effects are expected to occur. The conceptual model tested by our moderated mediation regression analyses is shown in Figure 1. Three types of patient reactions (behavioral resistance, hostility, and lack of appreciation) were examined as potential mediators of the effects of spousal social control in separate moderated mediation regression analyses. Each of these analyses also simultaneously examined patient adherence as a potential moderator of the link between patients’ reactions to social control and spouse burden (consistent with the conceptual model shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Moderated mediation model of the effects of social control on spouse burden.

The analyses were performed using a SPSS program by Preacher and Hayes (2004; 2008), and analyzed using SPSS/PASW version 18. In addition to examining significance levels of p < .05, we also used bootstrap estimates to calculate indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals, as recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002).

As shown in Table 2, the results revealed that patients’ behavioral resistance did mediate the association between spousal social control and spouse burden and, as expected, this mediation was evident only when patients’ dietary adherence was low. Specifically, the indirect association between spousal social control and spouse burden through patients’ behavioral resistance was significant for spouses who perceived that their partners were not adhering well to their dietary regimen (indirect effect estimate = .07, p < .05; CI (.02, .15)). The mediating effect of hostility was marginal and, as expected, it too was observed only when patients’ dietary adherence was low (indirect effect estimate = .08, p = .06; CI (.00, .18)). When patients were adhering well to their diet, no indirect effects of patient resistance and patient hostility were observed. Patients’ level of appreciation for their spouses’ involvement in their health did not mediate the link between spousal social control and spouse burden at any level of adherence.

Table 2.

Patients’ dietary adherence as a moderator of the indirect effects of social control on spouse burden (N = 157)

| Mediator: Patient behavioral resistance |

Mediator: Patient hostility |

Mediator: Patient appreciation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | |||

| Social control → mediator |

.23(.07)** | .28 (.11)* | .01 (.11) | |||

| Social control → spouse burden |

.27(.09)** | .25(.09)** | .33 (.09)*** | |||

| Mediator → spouse burden |

.29(.11)** | .29(.07)*** | −.07 (.08) | |||

|

Conditional indirect effects |

Estimatea | CIbootstrapb | Estimatea | CIbootstrapb | Estimatea | CIbootstrapb |

| Low patient adherence | .07 (.03)* | .02, .15 | .08 (.05)+ | .00, .18 | −.01 (.01) | −.04, .02 |

| High patient adherence | .01 (.07) | −.11, .20 | .01 (.06) | −.09, .18 | .01 (.02) | −.03, .06 |

p = .06;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Note. Each vertical panel represents a separate moderated mediation regression analysis that simultaneously examined direct effects (social control to the mediator, social control to spouse burden, the mediator to spouse burden) and conditional indirect effects (i.e., indirect effects that were conditional upon, or moderated by, the level of patient adherence). Covariates included in each analysis were gender, age, self-rated health, depressive symptomatology, time since patient diagnosis, and marital quality.

Bootstrapped estimates of indirect effects of social control on spouse burden through each mediator.

Bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

Relatively little research has examined whether spouses incur any costs from involvement in their marital partners’ chronic conditions by exerting health-related social control. Accordingly, the current study sought to address this gap by investigating whether exerting social control on a marital partner with type 2 diabetes was associated with spouse burden, as well as what mechanisms mediated for the association between social control and spouse burden and under what conditions this mediation occurred. Theoretical perspectives on both social control and caregiver burden were used to formulate hypotheses and interpret the associations observed.

Association between Social Control and Spouse Burden

We found that spouses experienced more burden the more that they attempted to regulate their partners’ dietary choices using social control. The burden could be due to the considerable responsibility associated with trying to ensure that their partners are correctly adhering to their medical regimen (Miller & Brown, 2005); the burden also could be due to the chronic nature of spouses’ involvement in the daily tasks required to manage type 2 diabetes. Researchers have suggested that providing social support or care to an ill partner may be conceptualized as a chronic stressor for the spouse, mainly due to the long-term commitment it entails (Revenson, Abraidad-Lanza, Majerovitz, & Jordan. et al., 2005). Moreover, ensuring that their partners are properly adhering to their diets may leave spouses with less time and energy for their own lives. In a study that examined the impact of caregiving for a chronically ill partner, researchers found that multiple areas of the partners’ lives were adversely affected, including their personal lives, social relations, and financial well-being (Baanders & Heijmans, 2007).

Mediating Role of Patients’ Responses to Social Control

Spouses experienced greater burden when their nonadherent partners reacted negatively to social control. Theory and research on the construct of miscarried helping (Coyne, Wortman, & Lehman, 1988) suggest that patients sometimes view their spouses’ involvement in their health as heavy-handed or otherwise miscalibrated, with resulting negative effects for both patients and spouses. Patients who are unwilling or unable to adhere to their diet may be particularly likely to resent their spouses’ social control efforts and to react with resistance and hostility. Patients’ behavioral resistance may be vexing to spouses because it defeats the very objective spouses had in mind when they sought to influence the patient to be more adherent. Thus, spouses may be likely to experience burden from exerting social control when they detect their partners to be engaging in behaviors such as hiding their unsound dietary behaviors, ignoring the spouses’ requests, or openly resisting the spouses’ requests by purposely increasing their unsound dietary behaviors. Such behavioral resistance may kindle spouses’ feelings of resentment or of being burned out by the constant effort to monitor their partners’ illness management. In addition, patients’ hostile reactions may be burdensome in their own right and also may contribute to strained marital interactions, further contributing to spouses’ feelings of burden. Indeed, researchers have found that trying to regulate the dietary behavior of a marital partner increases the risk of relationship tensions and conflicts (e.g., Denham, Manoogian, & Schuster, 2007; Trief et al., 2003).

Behavioral resistance and hostility, but not appreciation, mediated the link between social control and spouse burden, and this pattern of results appears to be consistent with research highlighting the salience of negative emotions and interactions (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001). Considerable evidence suggests that negative social exchanges have a greater impact than do positive exchanges (e.g., Newsom, Rook, Nishishiba, Sorkin, & Mahan, 2005; Rook, 1998), and spouses may be likely to experience patients’ behavioral resistance and hostility as more distinctly negative than the absence of patients’ appreciation by patients.

Moderating Role of Patients’ Adherence

The moderated mediation analyses helped to reveal when patients’ negative reactions were especially likely to account for the link between spousal social control and spouse burden. In particular, this indirect association occurred when patients were not adhering well to their diets. Research has shown that spouses who do not want to be involved in their partners’ health usually become involved anyway if their partners are not adhering properly to their medical regimen (Miller & Brown, 2005). Thus, when spouses feel that continued efforts will be needed in the future to promote adherence, such reluctant or unrewarding involvement clearly could feel burdensome. In addition, feelings of burden may stem from frustration or disappointment that one’s efforts to promote adherence were not successful. When spouses’ partners are adhering well to their medical regimen, in contrast, spouses may worry less and feel less need to continue monitoring their partners’ health behavior. The spouses may gain confidence that their partners will manage their diabetic diet well and, if they lapse, will not resist the spouses’ involvement; these conditions may help to reduce spouses’ feelings of burden.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the current study and directions for future research should be noted. First, the current study was cross-sectional and thus, we were unable to disentangle the temporal order of effects, or estimate the cumulative toll on the spouse of exerting health-related social control. A key concern is that spouses who are in worse physical or psychological health might be more likely to experience burden. Our analyses controlled for spouse self-rated physical health and depressive symptomatology, however, and still revealed a significant association between exerting social control and spouse burden, which argues against this alternative explanation. Despite the cross-sectional design, this study is among the first to attempt to delineate potential spousal effects from exerting social control. In the future, it would be advantageous to examine how spousal involvement changes over time to capture the long-term interpersonal processes that unfold in these couples as a function of managing a chronic condition. In addition, the current study gauged the effects of spouses’ involvement in their partners’ health on only certain aspects of the spouses’ lives. Future research might examine additional aspects of spouses’ health and well-being (e.g., psychological and physiological markers of stress) that might be associated with exerting social control (see Baanders & Heijmans, 2007). Furthermore, the results of the current study cannot be generalized to other social network members, such as cohabiting partners, friends, or adult children, who might be involved in chronically ill individuals’ disease management. Moreover, given the increasing prevalence of cohabitation (Seltzer, 2004), and evidence that unmarried adults tend to have different sources of social control than do married adults (August & Sorkin, 2010; Umberson, 1992), understanding whether the effects of engaging in social control attempts differs for cohabiting partners versus spouses warrants attention in future research. Finally, diabetes is a condition in which daily adherence to a diabetic diet is a critical aspect of disease management, and the current results cannot be assumed to be generalizable to other health conditions with different disease characteristics and regimens. The consequences of exerting social control may be different when spouses seek to be involved in their partners’ management of illnesses with a less demanding and complex daily regimen than type 2 diabetes.

In conclusion, the current study examined whether spousal efforts to exert health-related social control on their chronically ill partners were associated with adverse spousal consequences in the context of managing a serious chronic condition – one that has begun to emerge as a major health threat in industrialized nations. The findings suggest that spouses whose partners are adhering poorly to a prescribed medical regimen and who react negatively to the spouses’ efforts to foster greater adherence may be especially vulnerable to experiencing burden. Results from this study have the potential to inform the design of interventions aimed at enhancing spouses’ ability to promote better medical regimen adherence and ultimately, better health in patients with type 2 diabetes – without compromising their own well-being.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [grant number R01 AG024833].

Contributor Information

Kristin J. August, University of California, Irvine, U.S.A.

Karen S. Rook, University of California, Irvine, U.S.A.

Mary Ann Parris Stephens, Kent State University, U.S.A..

Melissa M. Franks, Purdue University, U.S.A.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl. 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August KJ, Sorkin DH. Marital status and gender differences in managing a chronic illness: The function of health-related social control. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71:1831–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baanders AN, Heijmans MJWM. The impact of chronic diseases: The partner’s perspective. Family and Community Health. 2007;30:305–317. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000290543.48576.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:323–370. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly EA, Penrod J, Wray LA. Living with type 2 diabetes: Marital perspectives of middle-aged and older couples. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing. 2007;45:25–32. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070201-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Smith DAF. Couples coping with a myocardial infarction: A contextual perspective on wives’ distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:404–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Wortman CB, Lehman DR. The other side of support: Emotional overinvolvement and miscarried helping. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Marshaling social support: Formats, processes, and effects. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 305–330. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Manoogian MM, Schuster L. Managing family support and dietary routines: Type 2 diabetes in rural Appalachian families. Families, Systems, and Health. 2007;25:36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ell K. Social networks, social support, and coping with serious illness: The family connection. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;42:173–183. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L, Chesla CA, Bartz RJ, Gilliss C, Skaff MA, Sabogal F, et al. The family and type 2 diabetes: A framework for intervention. Diabetes Educator. 1998;24:599–607. doi: 10.1177/014572179802400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks MM, Wendorf CA, Gonzalez R, Ketterer M. Aid and influence: Health-promoting exchanges of older married partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2004;21:431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner SS, Kenyon DB. Understanding “Good Days” and “Bad Days”: Emotional and physical reactivity among caregivers for elder relatives. Family Relations. 2007;56:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Butterfield RM. Antecedents and reactions to health-related social control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:416–427. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology. 1999;18:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Stephens MAP, Druley JA, Wojno WC. Negative reactions to received spousal care: Predictors and consequences of miscarried support. Health Psychology. 2002;21:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNabb WL. Adherence in diabetes: Can we definite it and can we measure it? Diabetes Care. 1997;20:215–218. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Brown JL. Marital interactions in the process of dietary change for type 2 diabetes. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2005;37:226–234. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Rook KS, Nishishiba M, Sorkin DH, Mahan TL. Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: Examining specific domains and appraisals. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60B:P304–P312. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.p304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychology and Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rees T, Freedman P. Social support moderates the relationship between stressors and task performance through self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28:244–263. [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA, Abraidod-Lanza AF, Majerovitz SD, Jordan C. Couples coping with chronic illness: What’s gender got to do with it? In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Social networks as a source of social control in older adults’ lives. In: Giles H, Coupland N, Wiemann J, editors. Communication, health, and the elderly. Manchester, England: University of Manchester Press; 1990. pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. Investigating the positive and negative sides of personal relationships: Through a lens darkly? In: Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR, editors. The dark side of close relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 369–393. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS, Ituarte PH. Social control, social support, and companionship in older adults’ family relationships and friendships. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS, Thuras PD, Lewis MA. Social control, health risk taking, and psychological distress among the elderly. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:327–334. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales E. Family burden and quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2003;12(Suppl. 1):33–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1023513218433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer JA. Cohabitation in the United States and Britain: Demography, kinship and the future. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens MAP, Fekete E, Franks MM, Rook KS, Druley JA, Greene K. Spouses’ use of persuasion and pressure to promote patients’ medical adherence after orthopedic surgery. Health Psychology. 2009;28:48–55. doi: 10.1037/a0012385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trief PM, Sandberg J, Greenberg RP, Graff K, Castronova N, Yoon M, et al. Describing support: A qualitative study of couples living with diabetes. Families, Systems, and Health. 2003;21:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS. Health-related social control within older adults’ relationships. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B:P387–P395. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.p387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Anders SL. Social control of health behaviors in marriage. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31:467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987;28:306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;34:907–917. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH. The Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale. An evaluation of its clinical utility. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:760–766. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]