Abstract

During vertebrate eye development, the transcription factor MITF acts to promote the development of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). In embryos with Mitf mutations, the future RPE hyperproliferates and is respecified as retinal tissue but only in a small portion of the dorsal RPE. Using a series of genetic crosses, we show that this spatial restriction of RPE respecification is brought about by persistent expression of the anti-retinogenic ventral homeodomain gene Vax2 in the dorso-proximal and both Vax1 and Vax2 in the ventral RPE. We further show that dorso-proximal RPE respecification in Vax2/Mitf double mutants and dorso-proximal and ventral RPE respecification in Vax1/2/Mitf triple mutants result from increased FGF/MAP kinase signaling. In none of the mutants, however, does the distal RPE show signs of hyperproliferation or respecification, likely due to local JAGGED1/NOTCH signaling. Expression studies and optic vesicle culture experiments also suggest a role for NOTCH signaling within the mutant dorsal RPE domains, where ectopic JAGGED1 expression may partially counteract the effects of FGF/ERK1/2 signaling on RPE respecification. The results indicate the presence of complex interplays between distinct transcription factors and signaling molecules during eye development and show how RPE phenotypes associated with mutations in one gene are modulated by expression changes in other genes.

Introduction

An ideal model to study domain specification during vertebrate central nervous system development is provided by the development of the eye. The eye’s neuroepithelial parts develop from a portion of the rostral neuroectoderm, the optic neuroepithelium, that forms the optic vesicle (OV) and becomes divided into the future retina, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and the optic stalk (OS). While it is known that these domain specifications involve both cell-extrinsic and cell-intrinsic mechanisms (for reviews see [1], [2], [3], many of the molecular details still need to be determined. For example, the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) regulates RPE specification and development but its integration into functional circuits is only partially understood [4]. In the mouse, Mitf is first expressed in the whole OV and then downregulated in the future neuroretinal domain by the visual system homeobox 2 (VSX2) protein [5], [6], [7], leaving it expressed in the presumptive RPE. Loss-of-function mutations in Mitf result in loss of pigmentation of the entire RPE combined with hyperproliferation and respecification of a small subdomain of the dorsal RPE as neuroretina [7], [8]. This suggests either that only the dorsal domain of the mutant RPE is exposed to retinogenic inducers that are strong enough to promote retinal development in the absence of Mitf, or that the remainder of the Mitf mutant RPE is subject to compensatory mechanisms that prevent full RPE-to-retina transitions.

Recent results have indicated that in mice with combined mutations in the transcription factors Coup-Tf1 and Coup-Tf2, the dorsal RPE and OS adopt a neuro-retinal fate and that this fate change is associated with a substantial reduction in the expression of the anti-retinogenic ventral homeodomain gene Vax1 in the dorsal OS and of Mitf in the dorsal RPE [9]. At early stages of development, Vax1 and its paralog Vax2 are first partially co-expressed, with Vax1 showing a gradient from the ventral OS into the ventral retina and Vax2 an inverted gradient from the ventral retina to the ventral optic stalk [10], [11], [12]. At later stages, the expression domains of Vax1 and Vax2 become segregated, with Vax1 predominantly found in the ventral OS and Vax2 predominantly found in the ventral retina [10], [11], [12]. The initial co-expression of Vax1 and Vax2 may explain why in Vax1/2 double mutants, ventral OS and retina develop as a hyperproliferating Pax6-positive retina-like domain and RPE development remains confined to the dorsal domain and in fact expands into the dorsal OS [13]. It was conceivable, therefore, that in Mitf mutants, compensatory upregulation of Vax1 and/or Vax2 are involved in the territorial limitation of RPE respecification as retina.

These observations prompted us to explore the role of Vax genes in Mitf mutant backgrounds. We find that in wild type, neither Vax1 nor Vax2 are normally present in the dorsal RPE, while in Mitf mutants, Vax2 (though not Vax1) is present in the future dorso-proximal RPE. Moreover, at time points when Vax1 and Vax 2 are segregated into ventral OS and retina in wild type, both Vax1 and Vax2 are retained in the presumptive ventral RPE domain in Mitf mutants. Furthermore, while individual Vax mutations do not grossly change Mitf expression in the presumptive RPE domains, Vax1/2 double mutants show ventral loss of Mitf expression and expansion of Mitf expression into the dorsal OS. Intriguingly, Vax1/2/Mitf triple mutants that retain at least one functional Vax gene copy show hyperproliferation of both dorsal and ventral RPE. In all these mutants, however, the future ciliary margin RPE remains intact, possibly brought about by JAGGED1-NOTCH signaling. The results underscore the complex interplay between distinct transcription factors and signaling molecules and highlight specific mechanisms by which mutations in individual genes can lead to compensatory gene expression changes that finally determine the phenotypic outcomes of these mutations.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All animal experimentations were approved by the NINDS/NIDCD animal care and use committee.

Mice

The Vax knock out alleles, Vax1tm1Grl and Vax2tm1Grl, here referred to as Vax1− and Vax2−, have been described [14], [15]. They were kept on a mixed C57BL/6;129S1/Sv background. The Mitf alleles Mitfmi-vga9 [4] and Mitfmi-ew [16], both functional null alleles and here referred to as Mitf −, were kept on a C57BL/6 background.

Immunofluoresence, Immunohistochemistry, in situ Hybridization, and RT-PCR

All histological analyses were performed according to previously published protocols [8], [17], [18]. For antigen retrieval, embryo sections were boiled in a microwave oven for 3 minutes in Tris-EDTA (pH 8.5). RT-PCR of dissected RPE and retina were done as described [8]. Antibodies, probes and primer sequences are shown in Table S1.

Optic Vesicle/Optic Cup Cultures

Optic primordia were obtained from wild-type and mutant embryos and cultured as described [7], as were bead implantations and western blots [7], [8], [19].

Whole Embryo Cultures

E10−10.5 wild-type embryos were prepared and cultured for 36 hours as described for optic vesicle/optic cup cultures, except that they were floating in the medium with the placenta attached though the amniotic membrane removed, and that DMSO as control or 10 µM γ-secretase inhibitor I (565750, EMD Millipore, USA) was added directly to the culture medium.

BrdU Incorporation

Pregnant mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 µg of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma, St. Louis) in phosphate buffer per gram of body weight. Mice were sacrificed and embryos collected at the indicated times.

Results

RPE-to-retina Transition in Mitf Mutants is Enhanced by Mutations in Vax1/Vax2

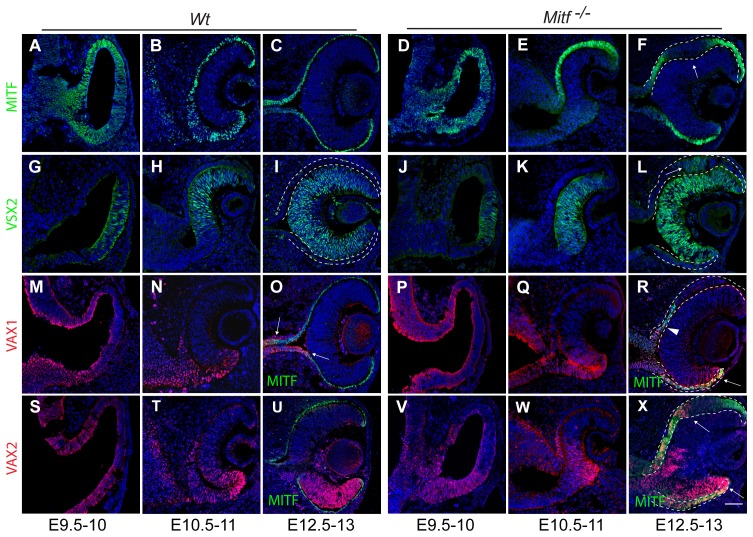

The studies described in this paper involved wild-type mice; mice carrying targeted alleles of Vax1 or Vax2, designated as Vax1− or Vax2−; and mice carrying either Mitfmi-ew, an allele expressing non-functional MITF protein, or Mitfmi-vga9, a transgenic insertional null allele lacking MITF protein expression. As the latter two alleles are functionally equivalent with respect to developmental eye defects, we designate them here as Mitf −. Figure 1 shows the expression patterns of the RPE protein MITF, the retinal protein VSX2 (visual system homeobox protein-2, formerly called CHX10) and VAX1 and VAX2 in wild-type and Mitf mutant embryos. In wild type, MITF and VSX2 expression at embryonic day (E) 9.5−12.5 was as previously described (Figure 1A–C,G-I) [7], [20]. Furthermore, as expected from previous in situ hybridizations [10], [11], [12], VAX1 and VAX2 protein were overlappingly expressed in the dorsal and ventral OV at E9.5 (Figure 1M,S) and in the ventral retina and RPE at E10.5 (Figure 1N,T). At later stages, however, VAX1 is only found in the optic stalk (Figure 1O; Figure S1A,B; arrows show the expression boundary between VAX1 and MITF) and VAX2 mostly in the ventral retina (Figure 1U; Figure S1F). Notably, no VAX proteins were found in dorsal or ventral RPE at this stage (Figure S1B,F). Before E10.5, Mitf −/− embryos showed no hyperproliferation of the dorsal RPE (compare Figure 1A with D) but such hyperproliferation became gradually apparent thereafter and resulted at E12.5 in a pronounced epithelial thickening in a small portion of the dorsal RPE, concomitant with downregulation of the (non-functional) MITF protein (Figure 1F, arrow; Figure S1C,G). This RPE portion expressed the retinal marker VSX2 (Figure 1L, arrow) and eventually developed as a laminated second retina as previously described [8], [19]. Furthermore, in such mutants, VAX1 was more prominent in the ventral RPE at E10.5 (Figure 1Q) where it stayed on at E12.5 (arrow in Figure 1R; arrowhead marks the VAX1 expression boundary in the dorso-proximal RPE; and Figure S1D), and VAX2 was more prominent in the dorso-proximal RPE at E10.5 (Figure 1W) and in both the dorso-proximal and all of the ventral RPE at E12.5 (arrows in Figure 1X and Figure S1H).

Figure 1. Expression patterns of MITF, VSX2, VAX1 and VAX2 in wild-type and Mitf mutant optic vesicles and cups.

Embryos of the indicated genotypes were harvested at the indicated times, cryosectioned, and labeled for the indicated proteins. Dorsal is up, and ventral down. The dotted lines mark presumptive RPE. (A–F) In both wild type (A–C) and mutants expressing non-functional MITF protein (D–F), optic vesicles initially show pan-vesicular MITF expression that in optic cups is extinguished in the presumptive retina and so becomes restricted to the presumptive RPE. Note that in mutants, MITF is downregulated in a portion of the dorsal RPE at E12.5 (F, arrow). Mitf downregulation in the retina is due to complimentary retinal expression of VSX2 (G–L). Note that the area of dorsal RPE thickening in mutants also expresses VSX2 (arrow in L). (M–R) VAX1 protein, present in wild type in presumptive ventral RPE at early stages (M,N) but absent later on (O, arrows) remains present in ventral RPE in mutant (R, arrow). Dorsally, VAX1 expression barely extends into the RPE (R, arrowhead). (S–X) VAX2 shows prominent ventral retina expression in wild type and mutant at E12.5 (U,X). In addition, it extends into both the dorsal as well as the ventral RPE in mutant (X, arrows). Single channel images of (R) and (X) are provided in Figure S1. Scale bar: 60 µm.

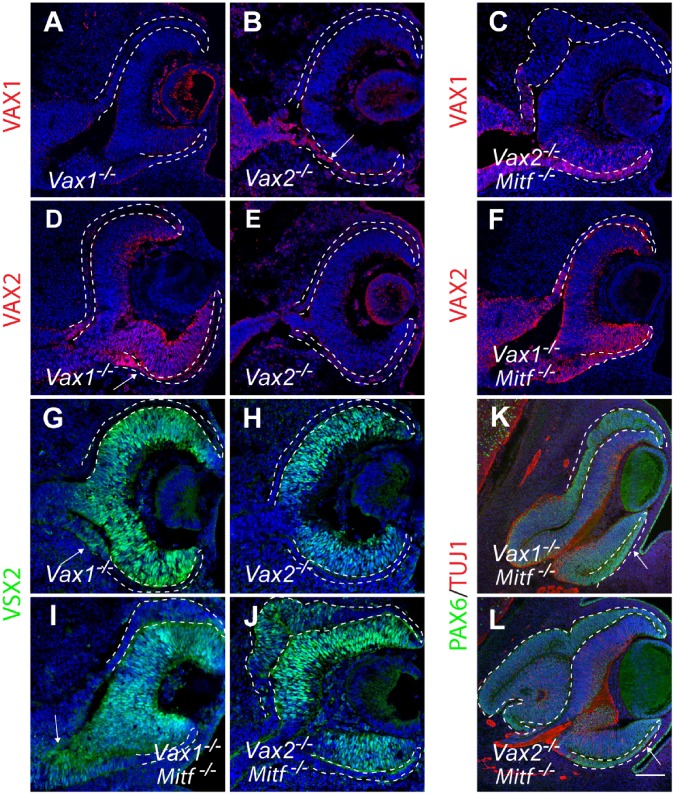

To directly test the possibility that retention of VAX proteins in the dorso-proximal and ventral RPE counteracts the phenotypic effects of Mitf mutations, we generated Vax1/Mitf and Vax2/Mitf compound mutants and compared them with the respective single mutants. In Vax1 or Vax2 single mutants, Mitf expression was not grossly changed in the presumptive RPE domains (Figure S1I,J), but VAX1 was retained in the ventro-proximal RPE of E12.5 Vax2 mutants (arrow in Figure 2B), and VAX2 was retained in the ventro-proximal RPE of E12.5 Vax1 mutants (arrow in Figure 2D). Nevertheless, the expression of PAX6 and PAX2, known to reciprocally repress each other’s functions to define the OS/optic cup boundary [21], was unchanged in all single mutants tested (Figure S1K–R). In the compound mutants, dorsal RPE thickening at E12.5 was much more pronounced in Vax2/Mitf mutants (Figure 2C) compared to Vax1/Mitf mutants (Figure 2F) or Mitf single mutants (see Figure 1F). This result likely reflects the fact that in Mitf mutants, VAX2 expression was retained in the dorso-proximal RPE (Figure 1X and Figure S1H) while VAX1 expression was not (Figure 1R and Figure S1D). The more pronounced dorsal RPE thickening in Vax2/Mitf double mutants was also reflected by a more pronounced expression of VSX2 in this area (compare Figure 2I with J). The difference between the two compound mutants became even bigger at E14.5, when the dorsal RPE of Vax2/Mitf mutants was massively expanded by comparison with that of Vax1/Mitf mutants (Figure 2K,L). The compound mutant RPEs also retained strong PAX6 expression (Figure 2K,L) while in wild-type RPE, PAX6 was gradually lost [19].

Figure 2. Vax mutations exacerbate the dorsal RPE phenotypes in Mitf −/− optic cups.

Coronal sections are from E12.5 embryos (A–F; G–J) and E14.5 embryos (K,L). (A,B,D,E) In Vax1 −/− mutants, VAX2 extends into the ventral RPE (D, arrow), and in Vax2−/− mutants, VAX1 extends into the ventral RPE (B, arrow). Absence of labeling on control sections (Vax1−/− labeled for VAX1, A, or Vax2−/− labeled for VAX2, E) indicates antibody-specificity. (C,F) Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− embryos show massive dorsal RPE hyperproliferation in areas negative for VAX1, but Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− embryos show little dorsal RPE hyperproliferation. (G,H,I,J) Corresponding sections labeled for VSX2. Note that VSX2 expression is absent in the dorsal RPE of Vax1−/− and barely visible in the dorsal RPE of Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− mutants (G,I), but present in the hyperproliferating dorsal RPE region of Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− mutants (J). Also note VSX2 expression at the ventro-proximal OS/RPE boundary in G,I (arrows) but absence of VSX2 expression in the ventral RPE. (K,L) Milder dorsal RPE thickening in E14.5 Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− mutants (K) compared to Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− mutants (L). Note that in both K,L, the ventral RPE remains largely unchanged at this stage (arrow). Scale bar: 60 µm (A–J); 130 µm (K,L).

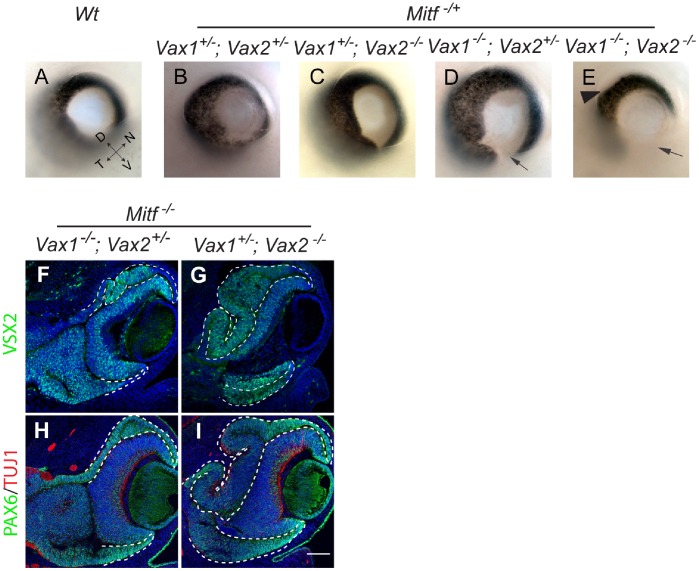

Interestingly, in none of the above compound mutants was there any thickening or VSX2 expression in the corresponding ventral RPE. This was conceivably due to the fact that in this domain, both VAX1 and VAX2 were overlappingly retained in Mitf mutants (see Figure 1Q,R,W,X and Figure S1D,H) and that either protein might compensate for the lack of the other. In fact, it has been observed previously that Vax1/Vax2 compound mutants show a massive thickening of the ventral optic neuroepithelium, with most cells positive for PAX6 and negative for PAX2, and none of them expressing the RPE marker DCT [13]. Consistent with these results, we find that although the dorsal RPE/OS of Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/+ mutants showed strong MITF expression, MITF expression was absent in the hyperproliferating ventral RPE/OS of such mutants or, interestingly, both dorsal and ventral RPE/OS in Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− mutants except at their distal margins (Figure S2A–C). We, therefore, reasoned that Vax1/Vax2/Mitf triple homozygotes might not show a phenotype in the ventral RPE beyond that of Vax1/2 double homozygotes. Hence, in order to test for Vax1/Vax2 redundancies in this domain, we left at least one copy of a Vax gene intact. Direct inspection of E14.5 eyes showed that as long as at least one copy of wild-type Mitf was retained, the presence of one copy of Vax1 (and none of Vax2) led to near normal ventral pigmentation (Figure 3C), the presence of one copy of Vax2 (and none of Vax1) only to a minor gap in ventral pigmentation (arrow in Figure 3D), and the absence of both Vax1 and Vax2 to loss of RPE pigmentation in the ventral eye as previously described for Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/+ mutants [13] (arrow in Figure 3E), and also in the dorsal proximal part of the eye (arrowhead in Figure 3E). In contrast, as shown in Figure 3F–I, in the total absence of functional Mitf, the presence of one copy of Vax2 (and none of Vax1, Figure 3F) or one copy of Vax1 (and none of Vax2, Figure 3G) led to ventral RPE thickening and increased VSX2 and PAX6 expression compared with the respective Vax1/Mitf or Vax2/Mitf compound mutants (see Figure 2). The triple mutants also showed a more pronounced dorsal RPE thickening and VSX2 expression compared with the respective Vax1/Mitf and Vax2/Mitf compound mutants. These results, summarized in Table 1, suggest that in the ventral RPE of Mitf mutants, Vax1 and Vax2 are indeed partially redundant for reducing retina transitions, while in the dorso-proximal RPE of Mitf mutants, Vax2 alone limits such retina transitions.

Figure 3. Vax1 and Vax2 redundantly limit retinogenesis in the presumptive dorso-proximal and ventral RPE domains of the Mitf mutant optic cups.

(A–E) In E14.5 Mitf +/− heterozygotes, RPE defects are Vax1 and Vax2 gene dose-dependent. In the total absence of Mitf (F–I), VSX2 and PAX6 expression are seen in the ventral RPE regardless of whether only one copy of Vax2 (F,H) or one copy of Vax1 (G,I) is present. Also note that dorsal RPE thickening and VSX2 and PAX6 expression are more prominent when VAX2 is totally missing (G,I) as opposed to when VAX1 is totally missing (F,H). Scale bar: 200 µm (A–E); 130 µm (F–I). Coordinates in (A): D – dorsal; V – ventral; T – temporal; N – nasal.

Table 1. RPE phenotypes in Vax1/Vax2/Mitf mutants.

| Genotypes | RPE phenotypes (Dorsal: D; Ventral: V; Proximal: P) | |||||

| Thickening/respecification | VSX2 expression | Pigmentation | Emergence age | |||

| Mitf −/− | D: + | V: − | D: + | V: − | Fully lost | E12−12.5 |

| Vax1−/− | D: − | V: − * | D: − | V: − * | V: coloboma | |

| Vax2−/− | D: − | V: − | D: − | V: − | V: mild coloboma | |

| Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− | D: +/− ** | V: − | D: +/− ** | V: − | Fully lost | E12.5 |

| Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− | D: +++ | V: − | D: +++ | V: − | Fully lost | E10.5 |

| Vax1−/−;Vax2+/−;Mitf −/− | D: ++ | V: + | D: ++ | V: + | Fully lost | E11.5 |

| Vax1+/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− | D: ++++ | V: ++ | D: ++++ | V: ++ | Fully lost | E10.5 |

| Vax1+/−;Vax2+/−;Mitf +/− | D: − | V: − | D: − | V: − | Overall less pigmented | |

| Vax1−/−;Vax2+/−;Mitf +/− | D: − | V: − | D: − | V: − | V: coloboma | |

| Vax1+/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− | D-P: +/− *** | V: − | D-P: +/− *** | V: − | D-P: +/− ***; V: mildcoloboma | E12.5 |

| Vax1−/−; Vax2−/−; Mitf +/− | D-P: +++ | V-P: + | D-P: +++ | V-P: + | D-P: −;V: severe coloboma | E10.5 |

In all mutants that are Vax1−/−, the prospective ventral RPE domain is present in the early optic vesicle/optic cup stage, but gradually displaced by the overgrowing presumptive ventral optic stalk domain that also abnormally contains VSX2-expressing cells, resulting in ventral coloboma after E14;

Interestingly, about 50% of the Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− embryonic eye sections showed only mild dorsal RPE phenotypes (see Figure 2F). It is possible that loss of VAX1 functions increases the local dosages of antiretinogenic factors such as VAX2, JAGGED1, or TFEC [19] but such changes may be too subtle to be detected by immunostaining or in situ hybridization.

Although the Vax1+/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− embryos appeared to have largely normal RPE pigmentation (Figure 3C), on sections there were some patches of thickened dorsal-proximal RPE subdomains that express VSX2 at very low levels.

The Role of FGF in Mitf Mutant RPE Development

The above observations suggest that the RPE- and OS-to-retina respecifications are associated with increased cell proliferation. In fact, BrdU incorporation assays showed increased DNA synthesis in E10.5 Mitf −/− RPE compared to the corresponding wild-type RPEs (Figure S3A–E). Earlier results also showed that MITF has prominent antiproliferative activities [22], [23], [24] and that FGF signaling reduces Mitf expression in the RPE and enhances cell proliferation [7], [25]. In addition, feedback loops may allow MITF to regulate the very signaling pathways that influence its own activities [26], [27], and so we tested whether Mitf and Vax1/2 mutations might exert their effects at least in part through changes in FGF signaling.

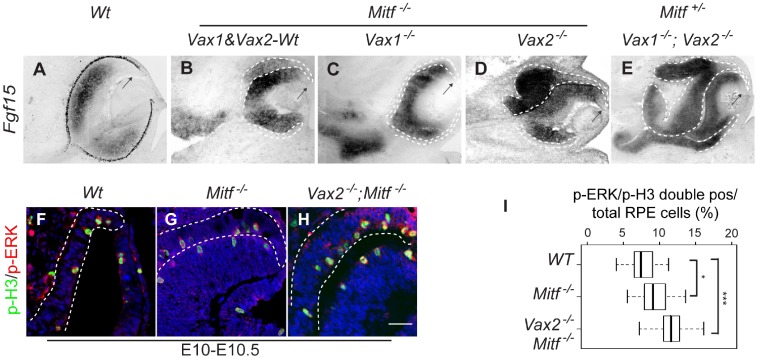

To test for the role of FGF signaling, we focused on FGF15. This factor is the major FGF expressed in the embryonic mouse retina but is absent in the RPE [19]. Nevertheless, RNA for its cognate receptors, FGFR1 and FGFR2, were found both in retina and RPE (Figure S3F). By in situ hybridization, Fgf15 was ectopically expressed in the dorsal RPE of Mitf −/− single mutants and even more prominently in the massively expanded RPE of Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− double and Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− triple mutants (Figure 4B,D,E), though only mildly in approximately half of Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− double mutants (Figure 4C). Nevertheless, high levels of FGF15 transcripts were seen in the abnormally thickened OS domains of both Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− (Figure 4C) and Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− mutants (Figure 4E). As expected from previous results studying the role of FGF1 and FGF2 [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], increased expression of FGF15 led to increased staining for activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) [17], [18], [33] in the dorsal RPE and correspondingly higher numbers of mitotic cells as evidenced by increased labeling for phospho-histone H3 (p-H3)-positivity (Figure 4F–I). We then confirmed the correlation between increased ERK1/2 signaling and RPE-to-retina transitions by applying the MEK inhibitor PD 98095 (MEKi) on heparing-acrylic beads to optic vesicle explant cultures as described previously [7]. As shown in Figure S3G, inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling in wild-type cultures reduced the levels of pERK, p-H3, and Cyclin-D, regardless of whether extra amounts of FGF were added or not. In fact, in similar experiments performed with Mitf −/− (Figure S3H–M) and Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− optic vesicle cultures (Figure S3N–P), inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling led to reduced numbers of p-H3-positive RPE cells and reduced expression of VSX2. Taken together, these results suggest that MITF and VAX proteins regulate FGF expression in the developing RPE and that in turn, as expected, FGF-ERK1/2 signaling then leads to increased cell proliferation and domain respecification.

Figure 4. FGF-MAP kinase signaling regulates RPE-to-retina transition in Mitf mutants.

(A–E) In situ hybridization for Fgf15. In wild type (A), Fgf15 is normally restricted to the neural retina but is absent in the distal retina (arrow). (B–E) Ectopic expression of Fgf15 in the dorsal RPE is seen in Mit −/− (B), Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− (D), and Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− (E) though not in Vax1−/−;Mitf −/− mutants (C). Note that as in wild type, the dorsal future ciliary margin shows little Fgf15 labeling (arrow in B–E). (F–H) Increased numbers of p-H3/p-ERK double-positive cells in the RPE of E10−10.5 Mitf −/− (G) and Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− mutant (H) as compared to wild-type RPE (F). (I) Quantitation of the results obtained from sections as in F–G. Box plots show minimal, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile and maximal percentages. Significance determined by Student’s t-test: *: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001 (2–3 sections per embryo, 6–10 embryos per genotype). Scale bar: 150 µm (A–E), 25 µm (F–H).

The Role of NOTCH Signaling in Mitf Mutant RPE Development

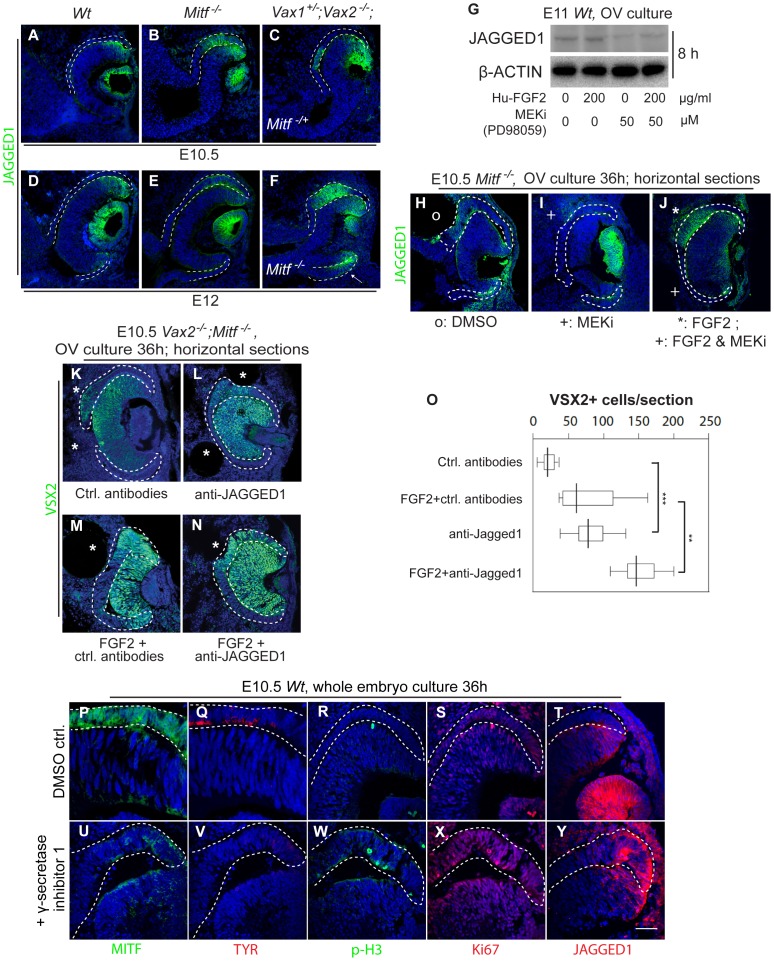

The above results showed a role for Vax genes to limit RPE-to-retina transition in the proximal portion of the RPE but did not address why RPE-to-retina transitions were also limited towards the distal RPE domain. In fact, in all single and double mutants and even the Vax1/Vax2/Mitf triple mutants, the distal RPE, which later contributes to ciliary body and iris, lacked expression of retinal markers, including VSX2 (for instance, Figures 1L; 2J; 3F,G and S4B,C,E,F), SOX2 (Figure S4B,C,E,F), and FGF15 (Figure 4A–E, arrows), and retained MITF expression and its monolayer characteristics (for instance Figures 1F,X; and Figure S2). Interestingly, at the OV stage, Jagged1, encoding a NOTCH ligand, is expressed in the lens placode and the dorsal future retina and then stays on in lens and distal retina ([34], [35]; and Figure 5A,D for JAGGED1 protein expression), and the gene encoding one of its receptors, NOTCH2, is expressed in the RPE including its distal tip [34], [35]. By comparison, Dll1, the gene encoding the NOTCH ligand DLL1, is initially expressed in the optic stalk and, once an optic cup is formed, expands into the proximal retina [34], [35]). Interestingly, JAGGED1 heterozygous mutations in humans cause anterior eye defects [36] as do mutations in the homologous gene in mice [37], [38]. It was conceivable, therefore, that in the mammalian optic cup, JAGGED1 might be one of the factors that limits retinal development in the distal RPE of Mitf and Vax/Mitf mutants.

Figure 5. JAGGED1-NOTCH regulates RPE proliferation and specification.

(A–F) Optic cups of the indicated genotypes were harvested at the indicated times and stained for JAGGED1. Note that in wild type and all indicated mutants, JAGGED1 is expressed in the dorsal distal retina and in (F) also in the E12.0 ventral distal retina and RPE (arrow), in addition to its prominent expression in the lens vesicle. Also note that a dorsal RPE subdomain in Mitf single or Vax1/2/Mitf triple mutants expresses JAGGED1 at both E10.5 and E12.0. (G) Western blots for the indicated proteins from wild-type OV cultures eight hours after exposure to human FGF2 and/or MEK1/2 inhibitor (MEKi). Note decrease in the level of JAGGED1 in the presence of MEKi. (H–J) JAGGED1 expression in sections of E10.5 Mitf −/− optic cups 36 hours after exposure to control beads (H, marked by o), MEKi bead (I, marked by +) or after co-implantation of an FGF2 bead (J, marked by *) and a bead coated with both FGF2 and MEKi (J, marked by +). Note that these are horizontal sections and that FGF2 and FGF2+MEKi have differential effects within the same OV culture. (K–N) Effects of antibody neutralization of JAGGED1 on VSX2 expression in Vax2−/−;Mitf −/− cultures. Compared to control antibodies (K), anti-JAGGED1 antibodies modestly increased VSX2 expression in the RPE (L) and further increased it when the beads were double-coated with FGF2 (N). Note that the anti-JAGGED1 effect in (L) is seen only in a subdomain of the RPE, consistent with the fact that JAGGED1 expression was confined to the thickening portion of the Mitf single and Vax/Mitf compound mutant RPE. (O) Quantitation of VSX2-positive cells in optic cup cultures. Box plots show minimal, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile and maximal percentages of VSX2-positive cells in the RPE per section (one section per embryo, and 8–9 embryos for each treatment). Significance determined by Student’s t-test: p<0.01 for control versus FGF2, and FGF2 versus FGF2+anti-JAGGED1; p<0.001 for control versus anti-JAGGED1, anti-JAGGED1 versus FGF2+anti-JAGGED1. (P–Y) Wild-type whole embryo cultures after 36-hour exposure to DMSO or NOTCH antagonist γ-secretase inhibitor 1. Note that under control conditions, RPE markers MITF (P) and TYROSINASE (TYR)(Q) were normally expressed, the numbers of phosphorylated histone H3 (p-H3) positive (R) and Ki67 positive (S) cells in the RPE were low, and JAGGED1 expression (T) was normal in the distal future retina. After γ-secretase 1 incubation, however, MITF and TYR expression was greatly reduced, the number of proliferative cells was elevated, and the expression territory of JAGGED1 expanded into the distal RPE (U–Y). Scale bar: 80 µm (A–F), 60 µm (H–N), 25 µm (P–Y).

In Mitf single or Vax/Mitf compound mutants, which as shown above are prone to RPE hyperproliferation and respecification, JAGGED1 was indeed retained at E10.5 and thereafter in the distal retina. It was, however, also present in the dorsal RPE, even when there was not yet any dorsal thickening at the early optic cup stage in some mutants (E10.5 Mitf −/− and Vax1+/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf −/+ mutants are shown in Figure 5B,C). In addition, in E12.5 Vax1/2/Mitf triple mutants, JAGGED1 was seen in the ventral distal RPE (arrow in Figure 5F, shown for Vax1+/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf −/−). Unlike JAGGED1, however, DLL1 did not show clear ectopic labeling in Mitf mutant RPE and so was unlikely to be a major contributor regulating distal RPE development (not shown).

While the presence of JAGGED1 in the distal retina was consistent with its presumed anti-retinogenic function for the NOTCH2-expressing adjacent RPE, its presence in the hyperproliferating RPE of Mitf mutants and Mitf/Vax compound mutants was intriguing as these RPE domains, unlike the distal retinal domains that develop as ciliary margin/ciliary body, develop as an expanded retina, and, for that matter, the underlying normal retina does not develop as an RPE. Hence, we reasoned that either JAGGED1 activity in the transdifferentiating RPE was counteracted by the massive expression of FGF/MAP kinase signaling described above, or that it was without activity, for instance for lack of an appropriate receptor. The latter, however, was unlikely as neuroretinal tissues express NOTCH3 [35] to which JAGGED1 binds [39]. To test for possible FGF/JAGGED1 interactions, we again resorted to the OV explant culture system. While addition of FGF2 did not markedly alter the levels of JAGGED1 in western blots of wild-type cultures kept for 8 hours, addition of MEKi, with or without additional FGF2, reduced its levels compared to β-actin (Figure 5G). To analyze these effects histologically, we then implanted beads coated with MEKi, FGF2, or FGF2+MEKi into Mitf −/− cultures. The results (Figure 5H–J) indicated locally decreased JAGGED1 expression in the vicinity of MEKi-coated or FGF2/MEKi doubly-coated beads and increased JAGGED1 expression in the vicinity of FGF2-coated beads. These results support the above observation that the dorsal hyperproliferating RPE domain of Mitf and Vax/Mitf mutants expressed JAGGED1 ligands in vivo. To address the question of whether JAGGED1 shows activity in this region, we used neutralizing JAGGED1 antibodies in Vax2/Mitf mutant OV cultures and assayed for changes in RPE histology and gene expression. In fact, anti-JAGGED1-coated beads led to a modest increase in VSX2 expression in a confined RPE domain, while beads coated with anti-JAGGED1 and FGF2 further increased the size of, and VSX2 expression, in the putative RPE domain (Figure 5L,N, quantitation of VSX2-positive RPE cells in Figure 5O). The results suggest that JAGGED1, which is expressed within the hyperproliferating RPE, partially counteracts the well-known pro-retinogenic effect of FGFs.

Constitutively active NOTCH signals can enhance RPE cell proliferation and lead to formation of pigmented tumors in the eye [40]. To test whether inhibiting NOTCH signaling would affect normal RPE development, E10.5 wild-type mouse embryos were cultured with or without a NOTCH-blocking compound, γ-secretase inhibitor I. As expected, in the 36-hour control group, the RPE of such cultured embryos showed normal MITF and TYROSINASE (TYR) expression (Figure 5P,Q), very few p-H3 and Ki67-positive cells (Figure 5R,S), and normal JAGGED1 expression in the future ciliary margin retina (Figure 5T & Figure S4G). With NOTCH activities blocked, however, MITF and TYR expression decreased sharply, the number of p-H3 and Ki67-positive cells in the RPE increased, and the JAGGED1-positive territory expanded into the distal RPE (Figure 5U–Y & Figure S4H). It appears, therefore, that NOTCH activity is required to determine the proper RPE/ciliary boundary and maintain normal cell proliferation and differentiation of the RPE. By extension, upregulated JAGGED1 in the dorsal RPE of Mitf and Mitf/Vax mutants, likely leading to upregulated NOTCH signaling in this domain, may function to partially counteract the strong FGF-ERK1/2 mediated RPE respecification. Nevertheless, it is likely that JAGGED1 acts in conjunction with other signaling and transcriptional mechanisms acting in the corresponding domains.

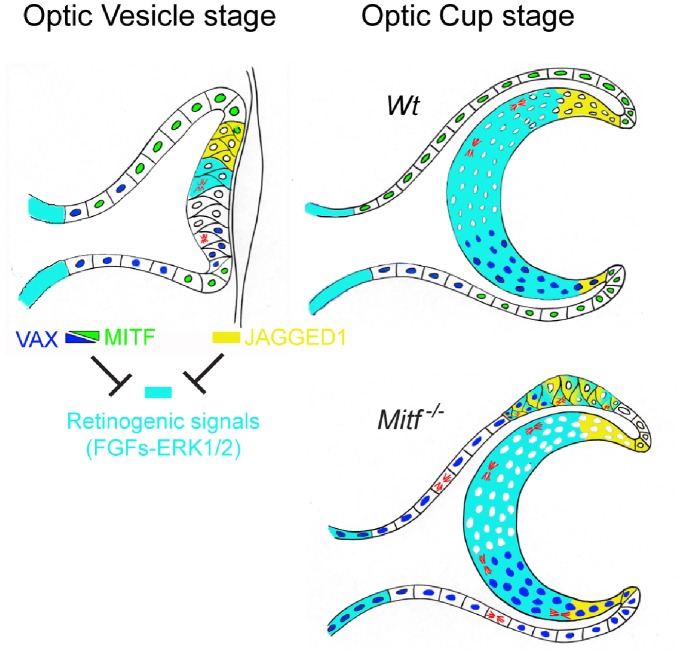

In sum, our results, summarized in Figure 6, indicate that in the proximal part of both the dorsal and ventral RPE, persistent expression of Vax genes are responsible for restricting Mitf-associated RPE transdifferentiation. In contrast, in the distal, anterior part, JAGGED/NOTCH signaling may prevail and so help to prevent transdifferentiation even in Vax1/2/Mitf triple mutants.

Figure 6. VAX, MITF and JAGGED1-NOTCH counteract FGF-ERK signaling in mediating proper compartmentalization of the optic neuroepithelium.

The genetic analyses presented in this paper suggest that at the optic cup stage, the gradients of VAX and MITF protein restrict the future neuroretinal domain to the central distal portion of the optic neuroepithelium. JAGGED1 expression, first dorsal and then ventral, counteract retinogenic signals in the future ciliary margin. Loss of MITF functions, such as due to loss-of-function mutations in its gene, lead to RPE abnormalities including a dorsally restricted RPE-to-retina transition mediated by strong local retinogenic FGF signals. These retinogenic signals are counteracted by the antiretinogenic VAX proteins that remain present in the RPE, helping to dorsally limit RPE respecification.

Discussion

It is well established that mutations of mouse Mitf and its orthologs in other species lead to abnormalities in the RPE that include loss of pigmentation, hyperproliferation, and eventual differentiation of a small dorsal subdomain as a second retina instead of RPE [4], [23], [25], [41], [42]. The mechanisms responsible for this dorsally restricted RPE respecification, however, are only partially understood. It has been shown that mutations in Vsx2 can alleviate [5], and reductions in Pax6 gene dose greatly exacerbate [19], the dorsal RPE pathology associated with Mitf mutations. Here, we investigated whether the ventral homeodomain proteins VAX1 and VAX2, known for their anti-retinogenic role during development [13], might also play a role in RPE respecification in Mitf mutants. Both proteins are normally expressed in the future RPE, though only at the OV stage and no longer at the later optic cup stage. Interestingly, we found that at the optic cup stage, Mitf mutations lead to an abnormal retention of VAX2 in the dorso-proximal RPE and of both VAX1 and VAX2 in the ventral RPE. Furthermore, introduction of targeted mutations in Vax2 into Mitf-mutant backgrounds allows for a shift of the dorso-proximal boundary of RPE hyperproliferation and VSX2 expression, and hence initiation of the retinal fate, towards the OS. Moreover, when only a single Vax gene copy was left intact, the ventral RPE also underwent efficient retinal re-specification. These results suggest that once present in the RPE, VAX1 and VAX2 counteract the FGF/MAP kinase-mediated hyperproliferation and retinal respecification. This interpretation is consistent with the earlier observation that combined early loss of these two proteins leads to giant retinae developing from the ventral optic neuroepithelium and OS [13].

It is conceivable that the effects of Vax1/2 in the RPE are not strictly due to their specific retention in the Mitf-mutant RPE but result from indirect effects of their normal expression in OS and ventral retina. Two observations, however, argue against this possibility. First, when Vax1, whose expression does not extend substantially into the dorso-proximal RPE of Mitf mutants, is lost, the proximal boundary of the dorsal RPE re-specification remains largely unchanged. In contrast, when Vax2, whose expression does extend into the dorso-proximal RPE of Mitf mutants, is lost, the proximal boundary of the dorsal RPE hyperproliferation and VSX2 expression zones are shifted proximally. Second, the Mitf mutant ventral RPE does not undergo re-specification as long as two copies of either Vax1 or Vax2 are present. In other words, it does not matter whether the remaining VAX protein is largely absent from the adjacent ventral retina, as is VAX1, or is present in the adjacent ventral retina, as is VAX2. We believe, in fact, that even the use of Cre-recombinase conditional Vax gene mutants might not easily allow for a clear discrimination between RPE-specific and indirect mechanisms as RPE drivers acting early may also affect the future OS and retina, and those acting later in the RPE may eliminate Vax genes too late to shift the boundaries of RPE re-specification. In any event, the results show that Vax genes can have anti-retinogenic activities not only in the future retina but also in the future RPE.

While the above considerations point to the role of Vax genes in helping to set the proximal boundaries of respecification of the Mitf-mutant RPE, they do not address the question of what mechanisms are responsible for setting the distal boundary of re-specification. It has previously been seen that many pathways including WNT [43], [44], [45], TGF-β [25] and BMP [46] signaling are persent around the ciliary margin. Here, we focused on NOTCH signaling because we found that the NOTCH ligand JAGGED1 was present in the dorsal distal retina of all mutants analyzed in this study and also in the ventral distal RPE of Vax1/2/Mitf mutants. The facts that NOTCH2, a JAGGED1 receptor, is expressed in the adjacent RPE [34], [35], and that inhibition of NOTCH signaling led to abnormal RPE development suggest that NOTCH signaling plays a critical role in keeping the distal RPE from differentiating into retina. More intriguing, however, was the observation that JAGGED1 was also seen in the hyperproliferating Mitf mutant dorsal RPE. It was conceivable, therefore, that this mutant RPE domain resembles the distal retinal domain of wild type. Nevertheless, the Mitf single or Vax2/Mitf double mutant dorsal RPE also expressed SOX2, a gene not normally found in the distal retina, and it expressed FGF15, which is also absent in the distal retina in wild type or any of the single and compound mutants tested in this study. In fact, direct assays for the activity of JAGGED1 using anti-JAGGED1 antibodies in Mitf mutant OV explant cultures suggested that JAGGED1 counteracts, at least partially, the Vax/Mitf/FGF-mediated RPE hyperproliferation and ectopic VSX2 expression. Hence, expression of Jagged1 in the mutant RPE may be seen as resulting from induction of a regulatory mechanism to limit RPE hyperproliferation and RPE-to-retina transitions. Interestingly, constitutive activation of NOTCH signaling using activated intracellular NOTCH in the RPE enhances RPE cell proliferation and results in the formation of pigmented tumors via an RBP-Jκ-dependent mechanism [40]. Nevertheless, we have not been able to clearly observe RBP-Jκ induction in the abnormal RPE of Mitf mutants and their various genetic combinations.

Supporting Information

Expression patterns of MITF, PAX6 and PAX2 remain largely unchanged in Vax1, Vax2 and Mitf single mutant optic cups. Single channel confocal images of MITF and VAX1, and MITF and VAX2 expression patterns in E12.5 wild type (Wt; A,B,E,F), and Mitf −/− (C,D,G,H). Arrows indicate the expression of VAX proteins in the Wt optic stalk (B) and Mitf −/− RPE (D,H). MITF expression is normal in the RPE of Vax1−/− (I) and Vax2−/− mutants (J). (K–R) Normal expression of PAX6 and PAX2 in retina and OS of Wt and mutant embryos. Note enhanced PAX6 expression in the dorsal RPE of Mitf −/− mutants, confirming previous observations [19]. Scale bar: 80 µm.

(TIF)

MITF expression in Vax1/Vax2 double mutants. Compared to wild type (A), MITF expression is expanded into the dorsal OS in Vax1/Vax2 double homozygous mutants at E14.5 (B). (C) Interestingly, Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− mutants show dorsal RPE thickening and loss of MITF expression in the dorso-proximal RPE but retention of MITF expression in the distal RPE. Scale bar: 180 µm.

(TIF)

The thickening of Mitf mutant RPE is associated with cellular hyperproliferation. BrdU was injected intraperitoneally into pregnant mice, and mice were sacrificed 2 hours thereafter. Embryos were fixed and sectioned coronally. Sections were stained with antibodies against BrdU and double labeled for CYCLIN D1 or Ki67. (A, B) At E10.5, BrdU/CYCLIN D1 double label in wild-type and Mitf −/− eyes. Already at this stage before overt dorsal RPE thickening, Mitf −/− RPEs show increased BrdU labeling compared to wild type. (C) Quantitation of BrdU positive cells/per total cells in the dorsal RPE subdomain of wild type and Mitf −/− embryos. Box plots show minimal, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile and maximal values of the respective percentages. Significance determined by Student’s t-test: ***: p<0.001. For quantitation, 6–10 embryos of each genotype and 2–3 sections per embryo were counted. (D, E) BrdU/Ki67 double label at E11.5. Note many BrdU+ and BrdU/Ki67 double-positive cells in mutant but not wild type RPE. (F) RT-PCR confirms the expression of FGF receptor-1 (Fgfr1) and 2 (Fgfr2) in both RPE and retinal domains. For details on tissue separation and RT-PCR conditions, see [8]. (G) Western blots for the indicated proteins in wild-type OV cultures of E10.5−11 embryos (n = 3) kept for 5 hours in DMEM serum-free medium in the presence or absence of human FGF2 and/or MEK1/2 inhibitor (MEKi) PD98059. Note reduction of p-ERK, p-H3, and CYCLIN D in presence of MEKi, regardless of whether FGF2 was added. (H–J; N–P) Mitotic cells (p-H3 positive) in Mitf −/− (H–J) and Vax2−/−; Mitf −/− (N–P) mutant RPE in OV cultures exposed for 36 hours to acrylic beads coated with FGF2, MEKi, or FGF2+MEKi. Note that these are horizontal sections and that placement of an FGF2 bead alone eventually leads to overgrowth of the entire RPE [7]. (K–M) VSX2 expression in Mitf −/− mutant RPE in OV cultures exposed for 36 hours to acrylic beads coated with FGF2, or FGF2+MEKi. Note VSX2 expression and overgrowth in the vicinity of the FGF2 bead and inhibition of VSX2 expression and overgrowth in the vicinity of the FGF2/MEKi bead. Images shown are from 1 embryo each out of 5 per conditions giving similar results. Scale bar: 60 µm (A, B, H–P); 25 µm (D); 15 µm (E).

(TIF)

(A–F) VSX2/SOX2 and (G,H) JAGGED1 expression in wild-type and Mitf single or Vax2/Mitf double mutant eyes. Note SOX2 and VSX2 expression in the thickened RPE of Vax2/Mitf double mutants at E10.5 (C, arrow) and both Mitf single and Vax2/Mitf double mutants at later stages (E,F). Also note that the distal RPE remains largely free of SOX2 staining, marking it as ciliary margin RPE. Wild-type whole embryo cultures (n = 3 per condition) exposed for 36 hours to DMSO (G) or NOTCH antagonist γ-secretase inhibitor 1 (H). Note that JAGGED1 is expressed in the distal RPE domains in presence of γ-secretase inhibitor 1. Scale bar: 60 µm (A–C, G, H), 80 µm (D–F).

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hiroaki Wake, Thomas Coate, and Zoe Mann for helpful comments on the manuscript, Prof. Constance Cepko for VSX2 antibody, and the NINDS/NIDCD animal Health and Care Section for excellent support.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Bharti K, Nguyen MT, Skuntz S, Bertuzzi S, Arnheiter H (2006) The other pigment cell: specification and development of the pigmented epithelium of the vertebrate eye. Pigment cell research/sponsored by the European Society for Pigment Cell Research and the International Pigment Cell Society 19: 380–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fuhrmann S (2010) Eye morphogenesis and patterning of the optic vesicle. Current topics in developmental biology 93: 61–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Graw J (2010) Eye development. Current topics in developmental biology 90: 343–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hodgkinson CA, Moore KJ, Nakayama A, Steingrimsson E, Copeland NG, et al. (1993) Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell 74: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horsford DJ, Nguyen MT, Sellar GC, Kothary R, Arnheiter H, et al. (2005) Chx10 repression of Mitf is required for the maintenance of mammalian neuroretinal identity. Development 132: 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rowan S, Chen CM, Young TL, Fisher DE, Cepko CL (2004) Transdifferentiation of the retina into pigmented cells in ocular retardation mice defines a new function of the homeodomain gene Chx10. Development 131: 5139–5152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nguyen M, Arnheiter H (2000) Signaling and transcriptional regulation in early mammalian eye development: a link between FGF and MITF. Development 127: 3581–3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bharti K, Liu W, Csermely T, Bertuzzi S, Arnheiter H (2008) Alternative promoter use in eye development: the complex role and regulation of the transcription factor MITF. Development 135: 1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang K, Xie X, Park JI, Jamrich M, Tsai S, et al. (2010) COUP-TFs regulate eye development by controlling factors essential for optic vesicle morphogenesis. Development 137: 725–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohsaki K, Morimitsu T, Ishida Y, Kominami R, Takahashi N (1999) Expression of the Vax family homeobox genes suggests multiple roles in eye development. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms 4: 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barbieri AM, Lupo G, Bulfone A, Andreazzoli M, Mariani M, et al. (1999) A homeobox gene, vax2, controls the patterning of the eye dorsoventral axis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96: 10729–10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hallonet M, Hollemann T, Wehr R, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, et al. (1998) Vax1 is a novel homeobox-containing gene expressed in the developing anterior ventral forebrain. Development 125: 2599–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mui SH, Kim JW, Lemke G, Bertuzzi S (2005) Vax genes ventralize the embryonic eye. Genes & development 19: 1249–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bertuzzi S, Hindges R, Mui SH, O’Leary DD, Lemke G (1999) The homeodomain protein vax1 is required for axon guidance and major tract formation in the developing forebrain. Genes & development 13: 3092–3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barbieri AM, Broccoli V, Bovolenta P, Alfano G, Marchitiello A, et al. (2002) Vax2 inactivation in mouse determines alteration of the eye dorsal-ventral axis, misrouting of the optic fibres and eye coloboma. Development 129: 805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steingrimsson E, Moore KJ, Lamoreux ML, Ferre-D’Amare AR, Burley SK, et al. (1994) Molecular basis of mouse microphthalmia (mi) mutations helps explain their developmental and phenotypic consequences. Nature genetics 8: 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ou J, Lowes C, Collinson JM (2010) Cytoskeletal and cell adhesion defects in wounded and Pax6+/− corneal epithelia. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 51: 1415–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ou J, Walczysko P, Kucerova R, Rajnicek AM, McCaig CD, et al. (2008) Chronic wound state exacerbated by oxidative stress in Pax6+/− aniridia-related keratopathy. The Journal of pathology 215: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bharti K, Gasper M, Ou J, Brucato M, Clore-Gronenborn K, et al. (2012) A Regulatory Loop Involving PAX6, MITF, and WNT Signaling Controls Retinal Pigment Epithelium Development. PLoS genetics 8: e1002757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu IS, Chen JD, Ploder L, Vidgen D, van der Kooy D, et al. (1994) Developmental expression of a novel murine homeobox gene (Chx10): evidence for roles in determination of the neuroretina and inner nuclear layer. Neuron 13: 377–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwarz M, Cecconi F, Bernier G, Andrejewski N, Kammandel B, et al. (2000) Spatial specification of mammalian eye territories by reciprocal transcriptional repression of Pax2 and Pax6. Development 127: 4325–4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Du J, Widlund HR, Horstmann MA, Ramaswamy S, Ross K, et al. (2004) Critical role of CDK2 for melanoma growth linked to its melanocyte-specific transcriptional regulation by MITF. Cancer cell 6: 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsukiji N, Nishihara D, Yajima I, Takeda K, Shibahara S, et al. (2009) Mitf functions as an in ovo regulator for cell differentiation and proliferation during development of the chick RPE. Developmental biology 326: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loercher AE, Tank EM, Delston RB, Harbour JW (2005) MITF links differentiation with cell cycle arrest in melanocytes by transcriptional activation of INK4A. The Journal of cell biology 168: 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mochii M, Mazaki Y, Mizuno N, Hayashi H, Eguchi G (1998) Role of Mitf in differentiation and transdifferentiation of chicken pigmented epithelial cell. Developmental biology 193: 47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schepsky A, Bruser K, Gunnarsson GJ, Goodall J, Hallsson JH, et al. (2006) The microphthalmia-associated transcription factor Mitf interacts with beta-catenin to determine target gene expression. Molecular and cellular biology 26: 8914–8927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yasumoto K, Takeda K, Saito H, Watanabe K, Takahashi K, et al. (2002) Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor interacts with LEF-1, a mediator of Wnt signaling. The EMBO journal 21: 2703–2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sakaguchi DS, Janick LM, Reh TA (1997) Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) induced transdifferentiation of retinal pigment epithelium: generation of retinal neurons and glia. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 209: 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhao S, Thornquist SC, Barnstable CJ (1995) In vitro transdifferentiation of embryonic rat retinal pigment epithelium to neural retina. Brain research 677: 300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guillemot F, Cepko CL (1992) Retinal fate and ganglion cell differentiation are potentiated by acidic FGF in an in vitro assay of early retinal development. Development 114: 743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pittack C, Jones M, Reh TA (1991) Basic fibroblast growth factor induces retinal pigment epithelium to generate neural retina in vitro. Development 113: 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park CM, Hollenberg MJ (1989) Basic fibroblast growth factor induces retinal regeneration in vivo. Developmental biology 134: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J (2003) Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development 130: 4527–4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bao ZZ, Cepko CL (1997) The expression and function of Notch pathway genes in the developing rat eye. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 17: 1425–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lindsell CE, Boulter J, diSibio G, Gossler A, Weinmaster G (1996) Expression patterns of Jagged, Delta1, Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 genes identify ligand-receptor pairs that may function in neural development. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 8: 14–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yuan ZR, Kohsaka T, Ikegaya T, Suzuki T, Okano S, et al. (1998) Mutational analysis of the Jagged 1 gene in Alagille syndrome families. Human molecular genetics 7: 1363–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCright B, Lozier J, Gridley T (2002) A mouse model of Alagille syndrome: Notch2 as a genetic modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency. Development 129: 1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xue Y, Gao X, Lindsell CE, Norton CR, Chang B, et al. (1999) Embryonic lethality and vascular defects in mice lacking the Notch ligand Jagged1. Human molecular genetics 8: 723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shimizu K, Chiba S, Kumano K, Hosoya N, Takahashi T, et al. (1999) Mouse jagged1 physically interacts with notch2 and other notch receptors. Assessment by quantitative methods. The Journal of biological chemistry 274: 32961–32969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schouwey K, Aydin IT, Radtke F, Beermann F (2011) RBP-Jkappa-dependent Notch signaling enhances retinal pigment epithelial cell proliferation in transgenic mice. Oncogene 30: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hallsson JH, Haflidadottir BS, Stivers C, Odenwald W, Arnheiter H, et al. (2004) The basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor Mitf is conserved in Drosophila and functions in eye development. Genetics 167: 233–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mochii M, Ono T, Matsubara Y, Eguchi G (1998) Spontaneous transdifferentiation of quail pigmented epithelial cell is accompanied by a mutation in the Mitf gene. Developmental biology 196: 145–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fujimura N, Taketo MM, Mori M, Korinek V, Kozmik Z (2009) Spatial and temporal regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is essential for development of the retinal pigment epithelium. Developmental biology 334: 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Westenskow P, Piccolo S, Fuhrmann S (2009) Beta-catenin controls differentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium in the mouse optic cup by regulating Mitf and Otx2 expression. Development 136: 2505–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu H, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Wallace VA (2003) Characterization of Wnt signaling components and activation of the Wnt canonical pathway in the murine retina. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 227: 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Muller F, Rohrer H, Vogel-Hopker A (2007) Bone morphogenetic proteins specify the retinal pigment epithelium in the chick embryo. Development 134: 3483–3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression patterns of MITF, PAX6 and PAX2 remain largely unchanged in Vax1, Vax2 and Mitf single mutant optic cups. Single channel confocal images of MITF and VAX1, and MITF and VAX2 expression patterns in E12.5 wild type (Wt; A,B,E,F), and Mitf −/− (C,D,G,H). Arrows indicate the expression of VAX proteins in the Wt optic stalk (B) and Mitf −/− RPE (D,H). MITF expression is normal in the RPE of Vax1−/− (I) and Vax2−/− mutants (J). (K–R) Normal expression of PAX6 and PAX2 in retina and OS of Wt and mutant embryos. Note enhanced PAX6 expression in the dorsal RPE of Mitf −/− mutants, confirming previous observations [19]. Scale bar: 80 µm.

(TIF)

MITF expression in Vax1/Vax2 double mutants. Compared to wild type (A), MITF expression is expanded into the dorsal OS in Vax1/Vax2 double homozygous mutants at E14.5 (B). (C) Interestingly, Vax1−/−;Vax2−/−;Mitf +/− mutants show dorsal RPE thickening and loss of MITF expression in the dorso-proximal RPE but retention of MITF expression in the distal RPE. Scale bar: 180 µm.

(TIF)

The thickening of Mitf mutant RPE is associated with cellular hyperproliferation. BrdU was injected intraperitoneally into pregnant mice, and mice were sacrificed 2 hours thereafter. Embryos were fixed and sectioned coronally. Sections were stained with antibodies against BrdU and double labeled for CYCLIN D1 or Ki67. (A, B) At E10.5, BrdU/CYCLIN D1 double label in wild-type and Mitf −/− eyes. Already at this stage before overt dorsal RPE thickening, Mitf −/− RPEs show increased BrdU labeling compared to wild type. (C) Quantitation of BrdU positive cells/per total cells in the dorsal RPE subdomain of wild type and Mitf −/− embryos. Box plots show minimal, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile and maximal values of the respective percentages. Significance determined by Student’s t-test: ***: p<0.001. For quantitation, 6–10 embryos of each genotype and 2–3 sections per embryo were counted. (D, E) BrdU/Ki67 double label at E11.5. Note many BrdU+ and BrdU/Ki67 double-positive cells in mutant but not wild type RPE. (F) RT-PCR confirms the expression of FGF receptor-1 (Fgfr1) and 2 (Fgfr2) in both RPE and retinal domains. For details on tissue separation and RT-PCR conditions, see [8]. (G) Western blots for the indicated proteins in wild-type OV cultures of E10.5−11 embryos (n = 3) kept for 5 hours in DMEM serum-free medium in the presence or absence of human FGF2 and/or MEK1/2 inhibitor (MEKi) PD98059. Note reduction of p-ERK, p-H3, and CYCLIN D in presence of MEKi, regardless of whether FGF2 was added. (H–J; N–P) Mitotic cells (p-H3 positive) in Mitf −/− (H–J) and Vax2−/−; Mitf −/− (N–P) mutant RPE in OV cultures exposed for 36 hours to acrylic beads coated with FGF2, MEKi, or FGF2+MEKi. Note that these are horizontal sections and that placement of an FGF2 bead alone eventually leads to overgrowth of the entire RPE [7]. (K–M) VSX2 expression in Mitf −/− mutant RPE in OV cultures exposed for 36 hours to acrylic beads coated with FGF2, or FGF2+MEKi. Note VSX2 expression and overgrowth in the vicinity of the FGF2 bead and inhibition of VSX2 expression and overgrowth in the vicinity of the FGF2/MEKi bead. Images shown are from 1 embryo each out of 5 per conditions giving similar results. Scale bar: 60 µm (A, B, H–P); 25 µm (D); 15 µm (E).

(TIF)

(A–F) VSX2/SOX2 and (G,H) JAGGED1 expression in wild-type and Mitf single or Vax2/Mitf double mutant eyes. Note SOX2 and VSX2 expression in the thickened RPE of Vax2/Mitf double mutants at E10.5 (C, arrow) and both Mitf single and Vax2/Mitf double mutants at later stages (E,F). Also note that the distal RPE remains largely free of SOX2 staining, marking it as ciliary margin RPE. Wild-type whole embryo cultures (n = 3 per condition) exposed for 36 hours to DMSO (G) or NOTCH antagonist γ-secretase inhibitor 1 (H). Note that JAGGED1 is expressed in the distal RPE domains in presence of γ-secretase inhibitor 1. Scale bar: 60 µm (A–C, G, H), 80 µm (D–F).

(TIF)

(DOCX)