ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Medical ethics is a critical component of the curriculum for clinical trainees. Educational initiatives should adapt content to participants’ experience in order to ensure relevance and retain their interest.

AIM

To develop and evaluate an experiential educational program for physicians.

SETTING

Academic medical center.

PARTICIPANTS

Senior internal medicine residents (n = 40).

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

A case-based didactic program was designed in which each resident shared a difficult ethics case from their clinical experience. We created a curriculum around these cases involving formal didactics as well as open-ended discussion and summarized the ethical issues most relevant to the participants. A course survey was administered based upon the validated Students’ Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ).

PROGRAM EVALUATION

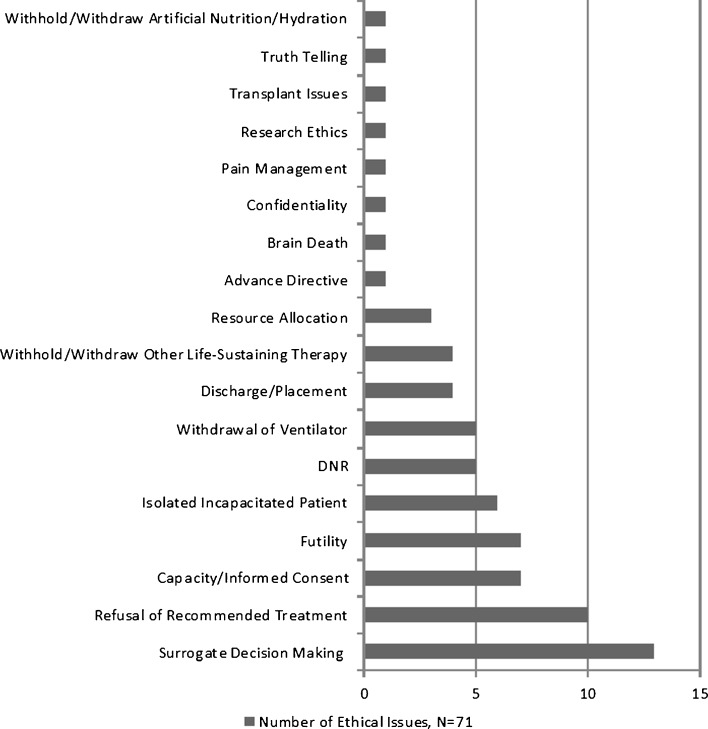

Common issues raised included surrogate decision-making (18 %), refusal of treatment (14 %), capacity/informed consent (10 %), and medical futility (10 %). Mean SEEQ subscale scores for learning value, organization/clarity, group interaction, breadth of coverage, and assignments/readings were 4.5 (maximum possible score 5). Residents unanimously rated the course overall as good/very good, and all agreed or strongly agreed that the course was useful and its structure effective.

DISCUSSION

An experiential case-based didactic program in medical ethics engaged adult learners and facilitated a comprehensive and clinically relevant educational initiative.

KEY WORDS: medical ethics, experiential learning, resident education

INTRODUCTION

Despite its importance, anyone charged with teaching medical ethics to residents encounters the daunting task of connecting with an often disengaged or resistant audience. While the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education1 mandates an understanding of and commitment to ethical principles, this very requirement may extinguish the enthusiasm necessary for effective study.

Medical ethics is a critical element of contemporary education for all clinicians. In a survey of medical students and resident physicians, the majority agreed that there was a need for formal training in medical ethics.2 While most physicians receive an introduction to clinical ethics in medical school, limited experiences at more formative stages may restrict their ability to assimilate this information and apply it to clinical practice.3 As such, residency is an ideal time to reinforce a framework in medical ethics.4,5 Data suggest that knowledge of the core themes within medical ethics diminishes with increasing postgraduate years of training, underscoring the need for continued education in ethics during residency.6

Common to all educational undertakings, the study of medical ethics is considerably more engaging when it is applied specifically to its intended audience. Participants have more meaningful educational experiences when curricula are based on personal experiences rather than standardized cases.7–11

We were asked to teach a required medical ethics course to our institution’s senior internal medicine residents during dedicated educational time. What started as a perceived obligation by residents became one of their highest rated educational experiences. We developed and implemented an innovative program in which residents volunteered cases that became the canvas for the course itself, capitalizing upon visceral, emotional reactions, and intertwining them within the educational experience to create a rewarding, successful program. From an empiric standpoint, the cohort served as a unique resource to better understand the most challenging medical ethical dilemmas for internal medicine residents.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

We developed and instituted a case-based didactic program in clinical medical ethics for internal medicine residents with the following course objectives: (1) to increase understanding of the theoretical, legal, and practical components of clinical ethics; (2) to apply these lessons to the inherent ethical challenges faced in clinical practice.

The course consisted of four 2-h small-group sessions among ten participants during a 2-week period, repeated four times in order to incorporate all 40 senior residents. We taught the course during an outpatient block that included dedicated educational time. Fellows in medical ethics (SMV and AGS) led the sessions, and the division chief (JJF) supervised the course. Residents received a syllabus with readings beforehand.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

In the weeks prior to the course, we solicited cases from each resident by asking them to provide a brief description of their “most difficult ethics case.” These case write-ups included enough clinical information to frame the ethical issue and a description of what was particularly challenging to them. Any potential patient identifiers were removed.

For each cohort of ten participants, eight cases were selected for discussion. We themed each session and commenced with two relevant case presentations, ensuring that the involved resident was present so that the he/she could provide further details as necessary for discussion. After presenting each case, we posed a series of questions aimed at guiding subsequent discussion. These cases also framed the ensuing 1-h session of formal didactics, presented in Microsoft PowerPoint® format. We followed each didactic session with a 1-h interactive discussion of the cases. We provided factual or experiential interjections and references back to the didactic presentation, although participants were encouraged to carry the majority of the discussion. While formal “ground rules” were not established, participants were encouraged to be critical but non-judgmental and were informed that variance in opinion was expected.

We recorded detailed “field notes” to capture the tenor and content of discussions. After the course, we categorized cases in accordance with a published ethics case classification schema to demonstrate the ethical issues most relevant to senior internal medical resident physicians.12

The solicited cases varied in topic and were broad in scope, facilitating a comprehensive course design within each cohort of participants. Illustrative sessions are summarized in Table 1, as each session was slightly different based upon the cases discussed. The salient ethical issues are summarized in Figure 1. Common contextual issues included interpersonal dispute/conflict, cultural/religious/ethnic factors, patient/family in denial, communication barriers, and quality of life.

Table 1.

Summary of Course Sessions

| Session | Title | Topics covered |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Professionalism and clinical pragmatism | Ethical principles; medical professionalism; confidentiality; goals of care; the role of ethics consultation |

| 2 | Informed consent and surrogate decision-making | Competence vs. capacity; assessing capacity; understanding informed refusal; substituted judgment and the best interest standard |

| 3 | New York State Law: What applies to you? | New York State Family Health Care Decision Act; health-care proxies; advance directives and living wills; DNR orders; withholding vs. withdrawing care; New York State Palliative Care Information Act |

| 4 | Ethics at the end of life | Goal setting; the doctrine of double effect; the role of palliative care consultation; medical futility; medical devices in terminal patients |

Figure 1.

Summary of ethical issues in solicited cases. *Total > 40 because many cases encompassed multiple issues.

Case Example

We present a sample case and excerpts from the ensuing discussion to illustrate the educational experience.

A 42-year-old man admitted overnight with cellulitis was vague about his code status preference on admission. The patient winked at the on-call resident, stating: “Listen hon, I’m not going to die today. I like to live a little dangerously so let’s say for right now that I’m going to take my chances and see what happens…. No chest compressions and no intubation. If things start heading south I may change my mind.” The resident did not place a DNR order in the chart, but she noted the patient’s comments and the need to further clarify his preference. The following morning, he developed acute respiratory failure. The team intubated him; he recovered and was extubated the following day. The team later discovered that the patient had overdosed on his own supply of illicit narcotics, which he had taken for chronic low back pain. The patient was grateful to the team for resuscitating him, and he remained full code for the remainder of the admission.

After introducing the case, we posed the following questions to the residents: What was the on-call resident’s duty with regard to clarifying code status? When is it necessary to address code status with patients? Did the patient make an autonomous decision about his code status initially? Should the patient have been intubated?

We followed these questions with the lecture “Ethics at the End of Life,” discussing how to communicate code status to patients and frame such conversations based upon goals of care.

After the lecture, the resident expanded upon case details, conveying frustration that the patient would not take the conversation seriously and worry that the consequences of haphazardly choosing to be DNR could have been dire had the team accepted the patient’s preference prima facie. The group of residents all reacted empathically, also expressing frustration about communicating with newly admitted patients about code status, as well as relief that their insecurities were neither unique nor unjustified. They identified barriers to effectively addressing code status in this setting, such as lack of continuity, lack of prior discussions with other providers, patients’ cognitive disconnect and denial, and insufficient time. The residents were also shocked about the poor survival rates after in-hospital resuscitation; few were familiar with these data.

Residents displayed mixed emotional reactions to the case. In addition to frustration, some expressed anger and worry that the patient evaded a serious conversation about code status and ultimately deceived the team about his possession of street drugs. Others simply shared their relief that the on-call resident did not enter the DNR order. The residents also discussed the dangers of medical handoffs when post-call, particularly the perceived difficulty in communicating intricate details concisely to an accepting physician.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

We designed a course survey based upon the validated Students’ Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ). The SEEQ is a reliable and psychometrically sound instrument with independently valid subscales.13 While developed for higher education, the SEEQ has been successfully implemented in medical education and other fields.14 We analyzed the following SEEQ subscales: Learning Value, Organization/Clarity, Group Interaction, Breadth of Coverage, and Assignments/Readings. Additional survey questions addressed participants’ opinions about medical ethics education in general and specific course elements. We gave respondents the opportunity to share unsolicited comments and suggest other topics. Descriptive statistics were calculated and presented.

The Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board evaluated the program and study protocol, deeming the study exempt from formal review. We asked residents to sign a release allowing publication of the details of the course and their case write-ups. To avoid implicit coercion or the suggestion that participation in the research study was mandatory for successful completion of the class, we requested consent at the end of the course.

Pedagogical Dynamics

We noted common themes throughout the classes. Residents were passive at the beginning of the course, but they quickly became more engaged, even by the end of the first session. In later sessions, they were more likely to interrupt lectures to ask questions, and they used medical ethics vocabulary more frequently and comfortably.

The residents identified several areas for quality improvement during discussions, including streamlining requests for ethics consultation, enhancing overnight supervision during codes by attending physicians, improving attempts to obtain signed health-care proxies at admission, and ensuring that admitting clinicians know about existing or previous DNR orders. All of these recommendations are being explored and/or implemented as a result of the program.

Finally, the residents discussed their general impressions of the course. While we did not measure moral distress, participants were relieved to have an opportunity to debrief and discuss emotionally weighty experiences. Many did not read the syllabus in advance because of time limitations and because they thought the didactic component was sufficient. However, they found the readings helpful for future reference; by request, reading materials remain accessible on a resident website.

Survey Results

Survey response rates were 100 %. SEEQ results are displayed in Table 2. All subscales were averaged in aggregate. All participants rated the course overall as good/very good, with a mean of 4.9 (SD 0.33). Residents unanimously agreed or strongly agreed that (1) medical ethics is a valuable component of medical education, (2) the case-based discussion component of the course was useful, and (3) the overall structure and design of the course was effective. The majority (95 %) agreed/strongly agreed that the didactic component of the course was effective.

Table 2.

Results of Student Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ) (n = 40)

| Subscale | Mean* | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Learning value | 4.69 | 0.33 |

| Organization/clarity | 4.49 | 0.42 |

| Group interaction | 4.86 | 0.64 |

| Breadth of coverage | 4.48 | 0.74 |

| Assignments/readings | 3.87 | 0.79 |

*Items scored on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)

For the overall course as well as each of its individual topics, 90 % of residents gauged the time allotment as “just right.” Approximately half of participants provided unsolicited comments. Of these, most were positive, regarding course format/organization, content, and group discussion/interaction.

DISCUSSION

We based our curriculum on solicited cases, merging structured and dialogue-based education to ensure relevance and engage participants. When residents knew the details of a case, they could carefully weigh risks and benefits through models of proportionality and clinical pragmatism in a more realistic manner frequently used by ethics consultants.15 In addition, residents were able to consider the unique evolution of each case, which is impossible with standardized cases. Because we tailored lectures to resident experience, they remained engaged. Having dedicated educational time ensured near-perfect attendance and overcame common barriers to teaching medical ethics to residents.16

Proximity of age among resident-students and fellow-instructors may have promoted more open and honest dialogue from students. Having dedicated ethics specialists who are also physicians also overcomes the problem of poor knowledge, confidence, and attitudes about teaching ethics by non-ethics faculty.17,18 Residents verbalized concerns about difficult cases in a safe, supportive forum, which also helped the course’s success.

The residents expressed several criticisms of the course in the survey comment section. Though hospital policies were not explicitly a part of our lectures, we addressed them informally during lectures and discussion; future courses might expand upon this component. The challenge of expecting busy medical residents to prepare course reading assignments is daunting, and our experience suggests that readings should be offered for reference rather than a requirement.

This study has notable limitations. Categorization of complex cases is challenging and imperfect. While the SEEQ is validated and widely utilized, it has not been used for this type of course. Thus, we chose relevant subscales and augmented with other, non-validated course-specific questions. We have not measured the lasting impact or reproducibility of the course over time. The identification of targets for quality improvement is also intriguing; however, the efficacy of implementation of such measures has yet to be elucidated.

Soliciting cases from participants for a didactic program in medical ethics successfully facilitated clinically relevant thinking and learning. By incorporating residents’ individual experiences into the curriculum, we brought experiential learning to post-graduate medical education. We believe these educational methods could be well suited to other aspects of residency training.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to members of the Division of Medical Ethics, Weill Cornell Medical College, for their review of the manuscript.

Funding/Support

None

Ethical Approval

The Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board evaluated the program and study protocol, and deemed the study exempt from formal review.

Previous Presentations

Abstract presented at the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (ASBH) 2012 annual meeting.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Requirements for Internal Medicine. 2009 edition; accessed 26 October 2012. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/140_internal_medicine_07012009.pdf.

- 2.Roberts LW, Warner TD, Hammond KA, Geppert CM, Heinrich T. Becoming a good doctor: perceived need for ethics training focused on practical and professional development topics. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29(3):301–309. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaldjian LC, Rosenbaum ME, Shinkunas LA, et al. Through students’ eyes: ethical and professional issues identified by third-year medical students during clerkships. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(2):130–132. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins HS. Teaching medical ethics during residency. Acad Med. 1989;64(5):262–266. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman HJ. Description of an ethics curriculum for a medicine residency program. West J Med. 1999;170(4):228–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulmasy DP, Geller G, Levine DM, Faden R. Medical house officers’ knowledge, attitudes, and confidence regarding medical ethics. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(12):2509–2513. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390230065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goold SD, Stern DT. Ethics and professionalism: what does a resident need to learn? Am J Bioeth. 2006;6(4):9–17. doi: 10.1080/15265160600755409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kon AA. Resident-generated versus instructor-generated cases in ethics and professionalism training. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2006;1(1):E10. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fins JJ, Nilson EG. An approach to educating residents about palliative care and clinical ethics. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):662–665. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klingensmith ME. Teaching ethics in surgical training programs using a case-based format. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(2):126–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wartman SA, Brock DW. The development of a medical ethics curriculum in a General Internal Medicine Residency Program. Acad Med. 1989;64(12):751–754. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198912000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilson EG, Acres CA, Tamerin NG, Fins JJ. Clinical ethics and the quality initiative: a pilot study for the empirical evaluation of ethics case consultation. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23(5):356–364. doi: 10.1177/1062860608316729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsh HW. SEEQ: a reliable, valid and useful instrument for collecting students’ evaluations of university teaching. Br J Educ Psychol. 1982;52:77–95. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1982.tb02505.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts C, Lawson M, Newble D, Self A, Chan P. The introduction of large class problem-based learning into an undergraduate medical curriculum: an evaluation. Med Teach. 2005;27(6):527–533. doi: 10.1080/01421590500136352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fins JJ, Bacchetta MD, Miller FG. Clinical pragmatism: a method of moral problem solving. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1997;7(2):129–145. doi: 10.1353/ken.1997.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strong C, Connelly JE, Forrow L. Teachers’ perceptions of difficulties in teaching ethics in residencies. Acad Med. 1992;67(6):398–402. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrese JA, McDonald EL, Moon M, et al. Everyday ethics in internal medicine resident clinic: an opportunity to teach. Med Educ. 2011;45(7):712–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sulmasy DP, Dwyer M, Marx E. Knowledge, confidence, and attitudes regarding medical ethics: how do faculty and housestaff compare? Acad Med. 1995;70(11):1038–1040. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199511000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]