Abstract

Prosthetic medical device-associated infections are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality rates. Novel improved materials and surfaces exhibiting inappropriate conditions for microbial development are urgently required in the medical environment. This study reveals the benefit of using natural Mentha piperita essential oil, combined with a 5 nm core/shell nanosystem-improved surface exhibiting anti-adherence and antibiofilm properties. This strategy reveals a dual role of the nano-oil system; on one hand, inhibiting bacterial adherence and, on the other hand, exhibiting bactericidal effect, the core/shell nanosystem is acting as a controlled releasing machine for the essential oil. Our results demonstrate that this dual nanobiosystem is very efficient also for inhibiting biofilm formation, being a good candidate for the design of novel material surfaces used for prosthetic devices.

Background

Staphylococcus aureus was recognized as a major pathogen soon after its discovery in the late nineteenth century. This organism causes a broad range of conditions, ranging from asymptomatic colonization to severe invasive infections which can progress to complicated septicemia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or endocarditis [1,2]. S. aureus is a major cause of nosocomial infections and is responsible for significant morbidity, mortality, and an extended hospital stay [3,4]. This Gram-positive bacterium possesses specific surface proteins such as fibronectin-binding proteins, collagen-binding proteins, and fibrinogen-binding proteins, which have been implicated as mediators in specific bacterial binding to the extracellular matrix and subsequent biofilm development [1,5-7].

The increased use of prosthetic devices during the past decades has been accompanied by a constantly increased number of prosthetic device infections [8]. S. aureus is a widespread bacterium, being found on the skin and mucosa of healthy persons; therefore, prosthesis-associated infections incriminating this pathogen are frequently encountered [9]. Prosthesis-associated infections could be the results of microbial colonization by three routes: (a) direct inoculation at the time of implantation, (b) hematogenous spreading during bacteremia, or (c) direct contiguous spreading from an adjacent infectious focus [10].

One of the most severe complications is a biofilm-associated infection of a prosthetic device due to the fact that biofilm bacteria are different from planktonic cells, being usually more resistant. The biofilm cells are resistant to all kinds of antimicrobial substances: antibiotics, antiseptics, disinfectants; this kind of resistance, consecutive to biofilm formation, is phenotypic, behavioral, and more recently, called tolerance [43,44].

Among the promising approaches to combat biofilm infections is the generation of surface modification of devices to reduce microbial attachment and biofilm development as well as incorporation of antimicrobial agents to prevent colonization. Essential oils (EOs) and their components are gaining increasing interest in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries because of their relatively safe status, their wide acceptance by consumers, and their exploitation for potential multi-purpose functional use [11].

Plants of the genus Mentha produce a class of natural products known as mono-terpenes (C10), characterized by p-menthone skeleton. Members of this genus are the only sources for the production of one of the most economically important essential oil, menthol, throughout the world [12]. Mentha piperita, commonly called peppermint, is a well-known herbal remedy used for a variety of symptoms and diseases, recognized for its carminative, stimulating, antispasmodic, antiseptic, antibacterial, and antifungal activities [4,13,14]. However, their use for clinical purposes is limited by the high volatility of the major compounds.

Due to their high biocompatibility [15] and superparamagnetic behavior, magnetite nanoparticles (Fe3O4) have attracted attention to their potential applications especially in biomedical fields [16,17], such as magnetic resonance imaging [18-20], hyperthermia [21], biomedical separation and purification [22], bone cancer treatment [21], inhibition of biofilm development [23,24], stabilization of volatile organic compounds [25], antitumoral treatment without application of any alternating magnetic field [26], drug delivery or targeting [27-33], modular microfluidic system for magnetic-responsive controlled drug release, and cell culture [34].This paper reports a new nano-modified prosthetic device surface with anti-pathogenic properties based on magnetite nanoparticles and M. piperita essential oil.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were used as received. FeCl3 (99.99%), FeSO4·7H2O (99.00%), NH3(28% NH3 in H2O, ≥99.99% trace metal basis), lauric acid (C12) (98.00%), CHCl3 (anhydrous, ≥99%, contains 0.5% to 1.0% ethanol as stabilizer),and CH3OH (anhydrous, 99.8%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Prosthetic device represented by catheter sections were obtained from ENT (Otolarincology), Department of Coltea Hospital, Bucharest, Romania.

Fabrication of nano-modified prosthetic device

For the fabrication of the nano-modified prosthetic device, we used a recently published method [35] in order to design a new anti-pathogenic surface coated with nanofluid by combining the unique properties of magnetite nanoparticles to prevent biofilm development and the antimicrobial activity of M. piperita essential oil.

M. piperita plant material was purchased from a local supplier and subjected to essential oil extraction. A Neo Clevenger-type apparatus was used to perform microwave-assisted extractions. Chemical composition was settled by GC-MS analysis according to our recently published paper [36].

Magnetite (Fe3O4) is usually prepared by precipitation method [37-39]. The core/shell nanostructure used in this paper was prepared and characterized using a method we previously described [40]. Briefly, sodium laurate (C12) was added under stirring to a basic aqueous solution of NH3, and then FeSO4/FeCl3 (1:2 molar ratio) was dropped under continuous stirring up to pH = 8, leading to the formation of a black precipitate. The product was repeatedly washed with methanol and separated with a strong NdFeB permanent magnet. The obtained powder was identified as magnetite by XRD. Dimension of the core/shell structure not exceeding 5 nm and their spherical shape were confirmed by TEM analysis. The FT-IR analysis identified the organic coating agent, i.e., lauric acid on the surface of the magnetite nanoparticles. In order to fabricate a modified surface of prosthetic device, core/shell/EO nanofluid was used to create a coated shell. The layer of core/shell/EO nanofluid on the prosthetic device was achieved by submerging the catheter pieces in 5 mL of nanofluid (represented by solubilized core/shell/EO in CHCl3 (0.33% w/v) aligned in a magnetic field of 100 kgf applied for 1 s.

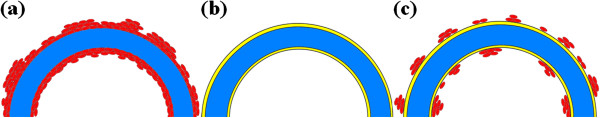

The catheter pieces were allowed to dry at room temperature. The rapid drying was facilitated by the convenient volatility of chloroform [41]. The coated prosthetic devices were then sterilized by ultraviolet irradiation for 15 min. Figure 1 presents a schematic representation of biofilm development on the surface of the prosthetic device coated/uncoated with anti-pathogenic nanofluid.

Figure 1.

Biofilm development on the surface of the prosthetic device coated/uncoated with anti-pathogenic nanofluid. (a)staphylococcal biofilm development on the surface of the prosthetic device, (b) nano-modified surface of the prosthetic device, (c) inhibition of staphylococcal biofilm development on the nano-modified surface of the prosthetic device.

TG analysis

The thermogravimetric (TG) analysis of theFe3O4@C12 and Fe3O4@C12@EO was followed with a Netzsch TG 449C STA Jupiter instrument (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). Samples were screened with 200 mesh prior to analysis, placed in an alumina crucible, and heated at 10 K·min−1 from room temperature to 800°C, under the flow of 20 mL min−1of dried synthetic air (80% N2 and 20% O2).

Biofilm development on nano-modified prosthetic device surface

The adherence of S. aureus ATCC 25923 was investigated in six multiwell plates using a static model for monospecific biofilm developing. Catheter pieces of 1 cm with and without coated shell were distributed in plastic wells (one per well) and immersed in the liquid culture medium represented by nutrient broth. The plastic wells were inoculated with 300 μL of 0.5 McFarland microbial suspensions and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After incubation the culture medium was removed, and the prosthetic device samples were washed three times in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in order to remove the nonadherent strains and moved into sterile wells. Then, fresh broth was added, the incubation being continued for 72 h. Viable cell counts (VCCs) have been achieved for both working variants (coated and uncoated prosthetic devices) after 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation, respectively, in order to establish the dynamics of the biofilm development and of the inhibitory effect exhibited by the proposed coating system. The adhered cells have been removed from the catheter sections by vortexing and brief sonication, and serial tenfold dilutions ranging from 10−4 to 10−12 of the obtained inocula have been spotted on Muller-Hinton agar, incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and assessed for VCCs [23,42]. All tests were performed in triplicate.

Characterization of biofilm development on the surface of nano-modified prosthetic device

After 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation, the samples prepared as described above were removed from the plastic wells, washed three times with PBS, fixed with cold methanol, and dried before microscopic examination. The biofilm development on the surface of coated and uncoated prosthetic devices was visualized using a Hitachi S2600N scanning electron microscope (SEM; Tokyo, Japan) at 25 keV, in primary electron fascicles, on samples covered with a thin silver layer.

Results and discussion

The increasing occurrence of multiresistant pathogenic bacterial strains has gradually rendered traditional antimicrobial treatment ineffective. The prognosis is worsened by the formation of bacterial biofilms on the biomaterials used in medicine, even if the planktonic cells are susceptible to some antibiotics. Public reports stated that 60% to 85% of all microbial infections involve biofilms developed on natural intact or damaged tissues or artificial devices [43]. These infections are characterized by slow onset, middle-intensity symptoms, chronic evolution, and high tolerance to antibiotics and other antimicrobials [44].

The efficiency of essential oils, polyphenolic extracts obtained from foregoing plants, and their synergic effects as alternative strategies for the treatment of severe infections caused by highly resistant bacteria was tested on the following species: methicillin-resistant S. aureus, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing Escherichia coli, and multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa[8]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the mint essential oil (Mentha sp.) exhibited synergistic inhibitory effects with low pH and sodium chloride against Listeria and inhibited some organisms such as S. aureus, E. coli, Candida albicans, Acinetobacter baumanii, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium, and Serratia marcescens[45]. The analyzed M. piperita EO proved to be rich in β-pinene, limonene, menthone, isomenthol, and menthol. These results are in concordance with reported literature [46,47]. We have suggested before the efficiency of nanosystem-vectored essential oil strategy [23]. The Fe3O4/C12 nanoparticles seem not to be cytotoxic on the HEp2 cell line, which is a great advantage for the in vivo use of these nanostructure systems for biomedical applications with minor risks of the occurrence of side effects [48].

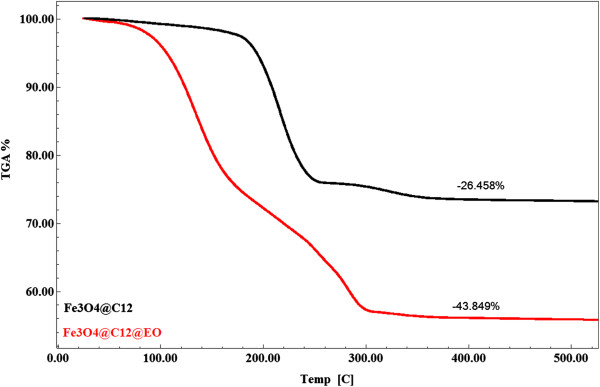

TG analysis is plotted in Figure 2. The mass loss of EO is up to approximately 170°C, while the mass loss of C12 is between 170°C and 375°C. To avoid errors due to overlapping the two regions of weight loss, EO content was estimated as the difference between weight loss for the region at approximately 375°C for both materials, and it is approximately 17.3%.

Figure 2.

TGA diagram of Fe3O4@C12 and Fe3O4@C12@EO.

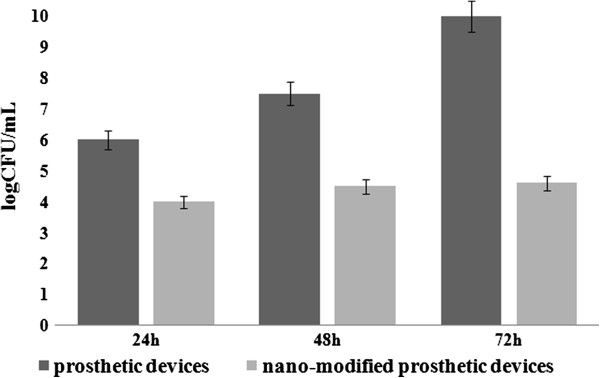

The dynamics of viable cells embedded in the biofilm developed on the catheter device samples showed a significant decrease of the biofilm viable cells, as compared with the uncoated surface (Figure 3). The number of biofilm-embedded cells at 24, 48, and 72 h was almost the same in the case of the coated surface. By comparison, in the case of the uncoated device surface, an ascendant trend of the VVCs was observed for the three analyzed time points. These results suggest that the antibiofilm effect of the obtained coating is remanent, probably due to the gradual release of the essential oil compounds from the coating.

Figure 3.

Viable cell counts recovered from S. aureus biofilms developed on the (nano-modified) catheter pieces. Samples were plated after 24h, 48h and 72h of incubation.

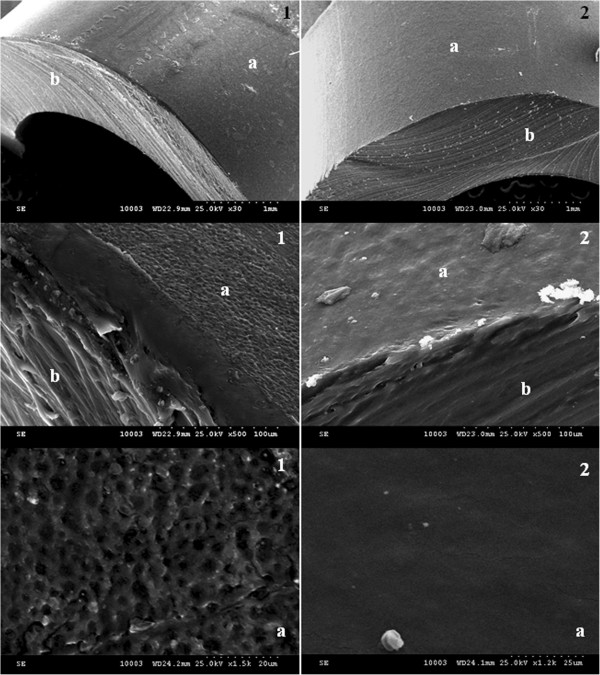

SEM images support the quantitative data, revealing the presence of a well-developed biofilm on the uncoated catheter, as compared with the functionalized one (Figure 4).Taken together, these results are demonstrating that the proposed solution for obtaining a nano-modified prosthetic device is providing an additional barrier to S. aureus colonization, an aspect which is very important for the readjustment of the treatment and prevention of infections associated with prosthetic devices.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of in vitro staphylococcal biofilm development on the surface of prosthetic devices. (1) Unmodified prosthetic device sections, (2) nano-coated prosthetic device sections, (a) surface of the prosthetic device, and (b) transversal section of the prosthetic device.

Conclusions

In this study, we report the fabrication of a 5 nm core/shell nanostructure combined with M. piperita essential oil to obtain a unique surface coating with improved resistance to bacterial adherence and further development of staphylococcal biofilm. The obtained results proved that the proposed strategy is manifesting a dual benefit due to its anti-adherence and microbicidal properties. The microbicidal effect could be explained by the stabilization, decrease of volatility, and controlled release of the essential oil from the core/shell nanostructure. The results reveal a great applicability for the biomedical field, opening new directions for the design of anti-pathogenic film-coated-surface-based core/shell nanostructure and natural products.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IA conceived of the study, provided the microbial strain, and drafted the manuscript together with AMG. AMG performed the fabrication of the nano-modified prosthetic devices, obtained the essential oil, and performed the biological analyses. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ion Anghel, Email: ionangheldoc@yahoo.com.

Alexandru Mihai Grumezescu, Email: grumezescu@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by the PN-II-PT-PCCA-2011-3.2-0284: ‘Novel nanostructured prosthetic tubular devices with antibacterial and antibiofilm properties induced by physico-chemical and morphological changes’ funded by the National University Research Council in Romania. We thank G. Voicu for the kind assistance with the SEM and TG, and M. C. Chifiriuc for helping with the biological analyses and useful discussions.

References

- Zhou H, Xiong ZY, Li HP, Zheng YL, Jiang YQ. An immunogenicity study of a newly fusion protein Cna-FnBP vaccinated against Staphylococcus aureus infections in a mice model. Vaccine. 2006;24:4830–4837. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polgreen PM, Herwaldt LA. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and nosocomial infections: implications for prevention. Curr Infect Dis Report. 2004;6:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s11908-004-0062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Werkum JW, Ten Berg JM, Thijs Plokker HW, Kelder JC, Suttorp MJ, Rensing BJWM, Tersmette M. Staphylococcus aureus infection complicating percutaneous coronary interventions. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banu O, Bleotu C, Chifiriuc MC, Savu B, Stanciu G, Antal C, Alexandrescu M, Lazǎr V. Virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains involved in the etiology of cardiovascular infections. Biointerface Res App Chem. 2011;1:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusela P. Fibronectin binds to Staphylococcus aureus. Nature. 1978;276:718–720. doi: 10.1038/276718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MK, Flock J-I. Fibrinogen-binding protein/clumping factor from Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2358–2363. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2358-2363.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speziale P, Raucci G, Visai L, Switalski LM, Timpl R, Hook M. Binding of collagen to Staphylococcus aureus. Cowan I J Bacteriol. 1986;167:77–81. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.77-81.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holban AM, Lazăr V. Inter-kingdom cross-talk: the example of prokaryotes - eukaryotes communication. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2011;1:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler VG, Fey PD, Reller LB, Chamis AL, Corey GR, Rupp ME. The intercellular adhesion locus ica is present in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from bacteremic patients with infected and uninfected prosthetic joints. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2001;189:127–131. doi: 10.1007/s430-001-8018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W. Prosthetic joint infection: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Infect Dis Report. 2000;2:377–379. doi: 10.1007/s11908-000-0059-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues L, Duarte A, Figueiredo AC, Brito L, Teixeira G, Moldao M, Monteiro A. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oils from the medicinal plant Mentha cervina L. grown in Portugal. Med Chem Res. 2012;21:3485–3490. doi: 10.1007/s00044-011-9858-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty A, Chattopadhyay S. Stimulation of menthol production in Mentha piperita cell culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Plant. 2008;44:518–524. doi: 10.1007/s11627-008-9145-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flamini G, Cioni PL, Puleio R, Morelli I, Panizzi L. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Calamintha nepeta and its constituent pulegone against bacteria and fungi. Phytother Res. 1999;13:349–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199906)13:4<349::AID-PTR446>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulluce M, Sahin F, Sokmen M, Ozer H, Daferera D, Sokmen A, Polissiou M, Adiguzel A, Ozkan H. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the essential oils and methanol extract from Mentha longifolia L. ssp. longifolia. Food Chem. 2007;103:1449–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros SF, Santos AM, Fessi H, Elaissari A. Stimuli-responsive magnetic particles for biomedical applications. Int J Pharm. 2011;403:139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao K, Song S, Ding J, Dou H, Sun K. Carbonyl groups anchoring for the water dispersibility of magnetite nanoparticles. Colloid Polym Sci. 2011;289:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s00396-011-2380-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Saviuc C, Holban A, Hristu R, Stanciu G, Chifiriuc C, Mihaiescu D, Balaure B, Lazar V. Magnetic chitosan for drug targeting and in vitro drug delivery response. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2011;1:160. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst QA, Thanh NKT, Jones SK, Dobson J. Progress in applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2009;42:224001. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/42/22/224001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mantle MD. Quantitative magnetic resonance micro-imaging methods for pharmaceutical research. Int J Pharm. 2011;417:173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger C, Pietzonka C, Heverhagen J, Kissel T. Novel magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with poly(ethylene imine)-g-poly(ethylene glycol) for potential biomedical application: synthesis, stability, cytotoxicity and MR imaging. Int J Pharm. 2011;408:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu E, Ficai M, Voicu G, Manzu D, Ficai A. Synthesis and characterization of collagen/hydroxyapatite – magnetite composite material for bone cancer treatment. J Mat Sci-Mat Med. 2010;21:2237–2242. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficai D, Ficai A, Alexie M, Maganu M, Guran C, Andronescu E. Amino-functionalized Fe3O4/SiO2/APTMS nanoparticles with core-shell structure as potential materials for heavy metals removal. Rev Chim (Bucharest) 2011;62:622–625. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Saviuc C, Chifiriuc MC, Hristu R, Mihaiescu DE, Balaure P, Stanciu G, Lazar V. Inhibitory activity of Fe3O4/oleic acid/usnic acid—core/shell/extra-shell nanofluid on S. aureus biofilm development. IEEE T NanoBioSci. 2011;10:269–274. doi: 10.1109/TNB.2011.2178263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anghel I, Grumezescu AM, Andronescu E, Anghel AG, Ficai A, Saviuc C, Grumezescu V, Vasile BS, Chifiriuc MC. Magnetite nanoparticles for functionalized textile dressing to prevent fungal biofilms development. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2012;7:501. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chifiriuc MC, Grumezescu V, Grumezescu AM, Saviuc CM, Lazar V, Andronescu E. Hybrid magnetite nanoparticles/Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil nanobiosystem with antibiofilm activity. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2012;7:209. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Andronescu E, Ficai A, Yang CH, Huang KS, Vasile BS, Voicu G, Mihaiescu DE, Bleotu C. Magnetic nanofluid with antitumoral properties. Lett Appl NanoBioSci. 2012;1:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Andronescu E, Ficai A, Bleotu C, Mihaiescu DE, Chifiriuc MC. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro assessment of the magnetic chitosan-carboxymethylcellulose biocomposite interactions with the prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Int J Pharm. 2012;436:771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu E, Grumezescu AM, Ficai A, Gheorghe I, Chifiriuc M, Mihaiescu DE, Lazar V. In vitro efficacy of antibiotic magnetic dextran microspheres complexes against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2012;2:332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang S, Liao Z, Zhao P, Su W, Niu R, Chang J. Folate-targeting magnetic core–shell nanocarriers for selective drug release and imaging. Int J Pharm. 2011;430:343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Mihaiescu DE, Tamaş D. Hybrid materials for drug delivery of rifampicin: evaluation of release profile. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2011;1:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Andronescu E, Ficai A, Saviuc C, Mihaiescu D, Chifiriuc MC. Deae-cellulose/Fe(3)O(4)/cephalosporins hybrid materials for targeted drug delivery. Rom J Mat. 2011;41:383–387. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaiescu DE, Horja M, Gheorghe I, Ficai A, Grumezescu AM, Bleotu C, Chifiriuc MC. Water soluble magnetite nanoparticles for antimicrobial drugs delivery. Lett Appl NanoBioSci. 2012;1:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Huang KS, Wang CY, Hsu YY, Chang FR, Lin YS. Microfluidic-assisted synthesis of hemispherical and discoidal chitosan microparticles at an oil/water interface. Electrophoresis. 2012;33(21):3173–3180. doi: 10.1002/elps.201200211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y-S, Huang K-S, Yang C-H, Wang C-Y, Yang Y-S, Hsu H-C, Liao Y-J, Tsai C-W. Microfluidic synthesis of microfibers for magnetic-responsive controlled drug release and cell culture. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anghel I, Limban C, Grumezescu AM, Anghel AG, Bleotu C, Chifiriuc MC. In vitro evaluation of anti-pathogenic surface coating nanofluid, obtained by combining Fe3O4/C12nanostructures and 2-((4-ethylphenoxy)methyl)-N-(substituted-phenylcarbamothioyl)-benzamides. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2012;7:513. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Chifiriuc CM, Marinaş I, Saviuc C, Mihaiescu D, Lazǎr V. Ocimum basilicum and Mentha piperita essential oils influence the antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus strains. Lett Appl NanoBioSci. 2012;1:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ficai D, Ficai A, Vasile BS, Ficai M, Oprea O, Guran C, Andronescu C. Synthesis of rod-like magnetite by using low magnetic field. Digest J Nanomat Biostruct. 2011;6:943–951. [Google Scholar]

- Manzu D, Ficai A, Voicu G, Vasile BS, Guran C, Andronescu E. Polysulfone based membranes with desired pores characteristics. Mat Plast. 2010;47:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaiescu DE, Grumezescu AM, Mogosanu DE, Traistaru V, Balaure PC, Buteica A. Hybrid organic/inorganic nanomaterial for controlled cephalosporins release. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2011;1:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Grumezescu AM, Andronescu E, Ficai A, Mihaiescu DE, Vasile BS, Bleotu C. Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of a magnetite/lauric acid core/shell nanosystem. Lett Appl NanoBioSci. 2012;1:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Saviuc C, Grumezescu AM, Chifiriuc MC, Bleotu C, Stanciu G, Hristu R, Mihaiescu D, Lazar V. In vitro methods for the study of microbial biofilms. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2011;1:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Saviuc C, Grumezescu AM, Bleotu C, Holban A, Chifiriuc C, Balaure P, Lazar V. Phenotipical studies for raw and nanosystem embedded Eugenia carryophyllata buds essential oil effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus strains. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2011;1:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar V, Chifiriuc C. Medical significance and new therapeutical strategies for biofilm associated infections. Rom Arch Microb Immunol. 2010;69:125–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clinical Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalemba D, Matla M, Smętek A. Antimicrobial activities of essential oils. Dietary Phytochem Microb. 2012;2012:157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lis-Balchin M, Deans SG, Hart S. A study of the variability of commercial peppermint oils using antimicrobial and pharmacological parameters. Med Sci Res. 1997;25:151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Maffei M, Sacco T. Chemical and morphometrical comparison between two peppermint notomorphs. Planta Med. 1987;53:214–216. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-962675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limban C, Grumezescu AM, Saviuc C, Voicu G, Predan G, Sakizlian R, Chifiriuc MC. Optimized anti-pathogenic agents based on core/shell nanostructures and 2-((4-ethylphenoxy)ethyl)-N-(substituted phenyl carbamothioyl)-benzamides. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:12584–12597. doi: 10.3390/ijms131012584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]