Abstract

Background

The utilization of medical care for gastrointestinal diseases increased over the past decade worldwide. The aim of the study was to investigate the difference between rural and urban patients in seeking medical service for gastrointestinal diseases at ambulatory sector in Taiwan.

Methods

From the one-million-people cohort datasets of the National Health Insurance Research Database, the utilization of ambulatory visits for gastrointestinal diseases in 2009 was analyzed. Rural patients were compared with urban and suburban patients as to diagnosis, locality of visits and choice of specialists.

Results

Among 295,056 patients who had ambulatory visits for gastrointestinal diseases in 2009, rural patients sought medical care for gastrointestinal diseases more frequently than urban and suburban patients (1.60 ± 3.90 vs. 1.17 ± 3.02 and 1.39 ± 3.47). 83.4% of rural patients with gastrointestinal diseases were treated by non-gastroenterologists in rural areas. Rural people had lower accessibility of specialist care, especially for hepatitis, esophageal disorders and gastroduodenal ulcer.

Conclusion

The rural–urban disparity of medical care for gastrointestinal diseases in Taiwan highlighted the importance of the well communication between rural physicians and gastroenterologists. Besides the establishment of the referral system, the medical teleconsultation system and the arrangement of specialist outreach clinics in rural areas might be helpful.

Keywords: Healthcare disparities, Gastroenterology, Rural health services, Utilization

Background

With the rapid development of gastroenterological science, the utilization of medical care for gastrointestinal (GI) diseases increased over the past decade worldwide [1-3]. The utilization of medical care for GI diseases might be influence by the predisposing factors (e.g. the demographics, social structure, occupation, race), enabling factors (e.g. income, insurance coverage, family resources, community resources) and need (e.g. the perceived need, clinically evaluated need) [4]. Besides, the health care system (e.g. health policy, resources, organization) and consumer satisfaction also played a role [5,6]. In the modern medical environment with networked collaboration, gastroenterologists as subspecialists are unlikely to treat all patients with GI diseases. Such a phenomenon can be also observed in other specialties [7,8]. Apart from the factor at the supply side, the socioeconomic and racial differences at the demand side resulted in the disparities of utilization of specialist care [9,10]. Additionally, geography also plays another important role. According to a study in Spain, the referral rate to the GI outpatient clinic was significantly higher in patients from urban areas than in those from rural areas [11]. On the other side, rural patients might have the risk of underutilization of adequate health care resources. Because the relevant literature is scarce, it deserves investigations whether the rural–urban disparities in GI care prevail universally.

The aim of our study was to conduct a nationwide, population-based study to investigate the difference between rural and urban patients in seeking medical service for GI diseases at ambulatory sector in Taiwan. Besides epidemiological measurements, our analyses of locations and specialties would be further stratified by disease group. Our results might also contribute to policy planning of health care resources as well as curricular design of continuing medical education for physicians practicing in rural areas.

Methods

Data sources

The data were obtained from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan. The National Health Insurance started in 1995 and enrolled 99% of 23 million residents in Taiwan. The monthly claims by the contracted health care facilities are processed electronically and later aggregated to form the NHIRD for research use [12,13]. We obtained the dataset of 1,000,000 people in NHIRD (Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005: LHID2005). This cohort dataset contained the claims data of 1,000,000 people randomly sampled from all National Health Insurance beneficiaries in 2005. According to the NHIRD, there was no significant difference in age and sex distribution between the beneficiaries in the LHID2005 and the whole beneficiaries in the National Health Insurance [14]. All claims data belonging to the cohort in the subsequent years were also extracted to form the specific dataset suitable for longitudinal follow-up analyses.

Study design

From the cohort dataset, we analyzed only data of ambulatory visits, excluding those to dental clinics, in 2009. The major diagnosis in each visit was used to identify the patients who sought medical help for GI problems. The diagnostic coding in the NHIRD was based on the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, version 9 (ICD-9-CM). To group diagnoses, we adopted the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) developed by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville in the USA [15]. In the CCS, all diagnoses in the ICD-9-CM were categorized into a small number of clinically meaningful categories. In the current study, the GI diseases were defined as those diagnoses under the single-level CCS categories 6, 12–18, 120, 135, 138–155, 214, 250, and 251. Among these categories, three were collective ones with a broader spectrum of disorders not categorized elsewhere. CCS 155 (other GI disorders) included constipation, dysphagia, irritable colon, celiac disease, functional diarrhea, intestinal fistula, perforation of intestine, etc. CCS 141 (other disorder of stomach and duodenum) included gastroparesis, gastric diverticulum, fistula, acquired hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, etc. CCS 151 (other liver diseases) included liver abscess, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, hepatic coma, ascites, jaundice, hepatomegaly, liver transplant status, etc.

From the claim record of each visit, we could identify the physician’s specialty. The identification number of the clinic in each visit could be linked to the town where the clinic was located. According to the definition of urbanization published by Taiwan’s National Health Research Institutes [16], all 365 townships in Taiwan were classified into 7 levels based on the following variables: population density (people/km2), population ratio of people with college or above educational levels, population ratio of elder people over 65 years old, population ratio of people of agriculture workers and the number of physicians per 100,000 people. To categorize the location in the current study, we operationally defined townships of levels 5–7 as rural, levels 3–4 as suburban and levels 1–2 as urban.

In the NHIRD, the information about each beneficiary’s residence was not available. To categorize the patients into rural, suburban and urban groups, we devised an algorithm on the basis of the location of physician clinics and local community hospitals in which the patients most frequently sought medical visits (not limited to GI diagnoses) during 2007 to 2009. If a patient sought medical visits at rural clinics and rural local community hospitals for more than or equal to 60% of such visits, she or he was deemed as a rural resident in our study. Suburban and urban residents were defined by the same rationale. If none of the above conditions existed, the patient was deemed as a migratory resident.

Other patient features under analysis included gender, age, GI diagnosis, as well as location of clinics, type of clinics (GI clinics or non-GI clinics) and number of visits for GI diseases. Groups of rural, suburban and urban patients would be compared.

Statistical methods

Data extraction and computation were performed with the Perl programming language, version 5.12.1 [17]. SPSS software (version 17) was used for statistical analysis. Besides the descriptive statistics, we used Pearson’s χ2 tests for categorical variables and ANOVA test for continuous variables. A p-value <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered as statistically significant.

Results

In 2009, only 879,240 beneficiaries in the cohort dataset had ambulatory visit records and 295,056 (33.5%) people had visits for GI diseases. Among the latter patient group, only 5.2% (n = 15,340) belonged to rural residents while about two-thirds (n = 193,705) belonged to urban, 15.6% (n = 46,083) to suburban and 13.5% (n = 39,928) to migratory residents.

Of all rural residents, 40.4% had visits for GI diseases during the year, higher than 38.2% in suburban residents and 35.6% in urban residents (Table 1). The mean number of visits for GI diseases by each rural resident in 2009 was also higher than those by each suburban and urban resident (1.60 ± 3.90 vs. 1.39 ± 3.47 and 1.17 ± 3.02, p < 0.001). In each resident group of different urbanization, female were more likely to have visits for GI diseases than males (p < 0.001) and people older than 65 years also sought medical help for GI diseases more frequently than younger people (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

The rural–urban divide in the number of patients and number of visits with GI diseases, stratified by gender and age

| |

Rural |

Suburban |

Urban |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficiaries | Pat. with GI disease (%) | No. of visits with GI disease per beneficiary (mean ± SD) | Beneficiaries | Pat. with GI disease (%) | No. of visits with GI disease per beneficiary (mean ± SD) | Beneficiaries | Pat. with GI disease (%) | No. of visits with GI disease per beneficiary (mean ± SD) | |

| Female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0-17 |

3654 |

1357 (37.1) |

0.79 ± 1.70 |

11886 |

4408 (37.1) |

0.82 ± 1.76 |

44476 |

16150 (36.3) |

0.79 ± 1.71 |

| 18-39 |

3261 |

1329 (40.8) |

1.27 ± 2.91 |

16293 |

6577 (40.4) |

1.18 ± 2.62 |

110506 |

42228 (38.2) |

1.05 ± 2.46 |

| 40-64 |

6664 |

3009 (45.2) |

1.77 ± 3.69 |

21141 |

8926 (42.2) |

1.64 ± 3.65 |

103375 |

39711 (38.4) |

1.43 ± 3.46 |

| > = 65 |

4464 |

2243 (50.2) |

2.48 ± 5.04 |

10493 |

4846 (46.2) |

2.26 ± 4.72 |

29858 |

12907 (43.2) |

2.07 ± 4.49 |

| Subtotal |

18043 |

7938 (44.0)* |

1.66 ± 3.71** |

59813 |

24757 (41.1)* |

1.46 ± 3.37** |

288215 |

110996 (38.5)* |

1.25 ± 3.05** |

| Male |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0-17 |

3971 |

1449 (36.5) |

0.78 ± 1.58 |

13037 |

4827 (37.0) |

0.78 ± 1.64 |

48661 |

17922 (36.8) |

0.79 ± 1.74 |

| 18-39 |

4242 |

1199 (28.3) |

0.81 ± 2.57 |

16399 |

4456 (27.2) |

0.77 ± 2.42 |

88672 |

23716 (26.7) |

0.70 ± 2.10 |

| 40-64 |

7480 |

2791 (37.3) |

1.77 ± 4.47 |

21394 |

7530 (35.2) |

1.54 ± 4.02 |

91968 |

29655 (32.2) |

1.26 ± 3.35 |

| > = 65 |

4236 |

1963 (46.3) |

2.66 ± 5.58 |

10007 |

4513 (45.1) |

2.48 ± 5.23 |

27082 |

11416 (42.2) |

2.24 ± 4.94 |

| Subtotal |

19929 |

7402 (37.1)* |

1.56 ± 4.07** |

60837 |

21326 (35.1)* |

1.32 ± 3.57** |

256383 |

82709 (32.3)* |

1.08 ± 2.99** |

| Total | 37972 | 15340 (40.4)* | 1.6 ± 3.90 | 120650 | 46083 (38.2)* | 1.39 ± 3.47 | 544598 | 193705 (35.6)* | 1.17 ± 3.02 |

* p <0.001 of Chi-square test for the no. and percentage of patients with GI diseases among different areas.

**p <0.001 of ANOVA test for the no. of visits with GI disease within the same gender among different areas.

GI: gastrointestinal; Pat: patients; SD: standard deviation.

About four-fifths of rural patients with GI diseases were treated at non-GI clinics in rural areas (83.4%, n = 12,796). When rural patients decided to visit gastroenterologists, urban GI clinics were more frequently chosen than suburban GI clinics (7.9% vs. 5.2%, p < 0.001). Compared with rural residents, urban and suburban residents were more likely to visit GI clinics (19.0% and 17.9% vs. 15.2%, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of clinics visited by patients with GI diseases, stratified by locality

| Rural patients no (%, n = 15340) | Suburban patients no (%, n = 46083) | Urban patients no (%, n = 193705) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural areas |

|

|

|

| GI clinics |

465 (3.0) |

74 (0.2) |

23 (0.0) |

| Non-GI clinics |

12796 (83.4) |

1597 (3.5) |

1534 (0.8) |

| Suburban areas |

|

|

|

| GI clinics |

791 (5.2) |

5232 (11.4) |

1205 (0.6) |

| Non-GI clinics |

2059 (13.4) |

38793 (84.2) |

5341 (2.8) |

| Urban areas |

|

|

|

| GI clinics |

1216 (7.9) |

3289 (7.1) |

35810 (18.5) |

| Non-GI clinics |

2117 (13.8) |

6781 (14.7) |

173645 (89.6) |

| All areas |

|

|

|

| GI clinics |

2333 (15.2)* |

8251 (17.9)* |

36815 (19.0)* |

| Non-GI clinics | 14637 (95.4) | 42914 (93.1) | 177209 (91.5) |

* p <0.001 of Chi-square test for the number and percentage of patients with GI diseases attending GI clinics among different residences.

GI: gastrointestinal.

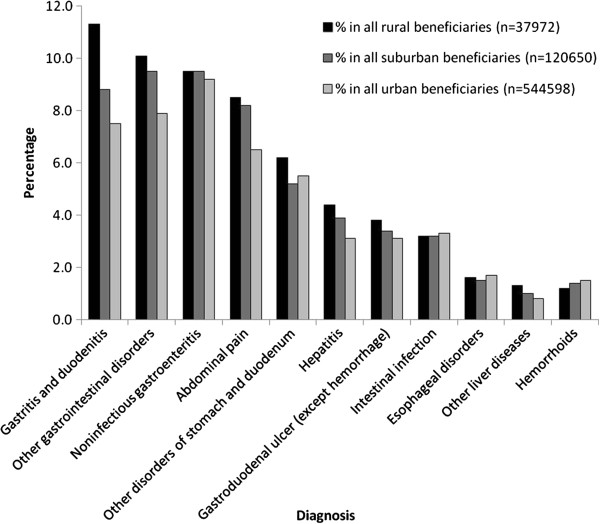

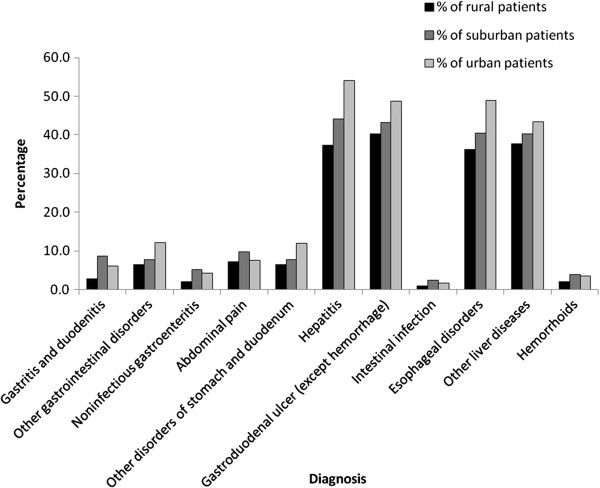

Patients of different urbanization had similar spectrums of GI diseases with slight discrepancy in ranking order (Table 3). Except intestinal infection, esophageal disorder and hemorrhoids, rural patients had higher prevalences of other kinds of GI diseases than urban patients (Figure 1). However, rural patients were less likely to visit GI clinics than suburban and urban patients in all kinds of GI diseases (Figure 2) and the differences were most striking in hepatitis (37.4% vs. 44.2% and 54.0%), esophageal disorder (36.3% vs. 40.5% and 48.8%) and gastroduodenal ulcer (40.2% vs. 43.1% and 48.7%, all p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Distribution of GI diseases, stratified by patient’s residence

| |

Rural |

Suburban |

Urban |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease groups according to clinical classifications software | No. of pat. | No. of pat. treated at GI clinics (%, n = No. of pat.) | No. of pat. | No. of pat. treated at GI clinics (%, n = No. of pat.) | No. of pat. | No. of pat. treated at GI clinics (%, n = No. of pat.) |

| Gastritis and duodenitis |

4287 |

117 (2.7) |

10669 |

927 (8.7) |

40721 |

2451 (6.0) |

| Other gastrointestinal disorders |

3844 |

246 (6.4) |

11507 |

0892 (7.8) |

43236 |

5287 (12.2) |

| Noninfectious gastroenteritis |

3600 |

76 (2.1) |

11417 |

586 (5.1) |

50078 |

2094 (4.2) |

| Abdominal pain |

3238 |

229 (7.1) |

9860 |

964 (9.8) |

35590 |

2702 (7.6) |

| Other disorders of stomach and duodenum |

2336 |

151 (6.5) |

6310 |

484 (7.7) |

30098 |

3624 (12.0) |

| Hepatitis |

1683 |

630 (37.4) |

4685 |

2070 (44.2) |

16671 |

9000 (54.0) |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer (except hemorrhage) |

1451 |

583 (40.2) |

4141 |

1784 (43.1) |

17004 |

8274 (48.7) |

| Intestinal infection |

1201 |

11 (0.9) |

3866 |

91 (2.4) |

18165 |

314 (1.7) |

| Esophageal disorders |

625 |

227 (36.3) |

1862 |

755 (40.5) |

9408 |

4587 (48.8) |

| Other liver diseases |

492 |

185 (37.6) |

1210 |

486 (40.2) |

4457 |

1936 (43.4) |

| Hemorrhoids | 456 | 9 (2.0) | 1673 | 65 (3.9) | 7998 | 283 (3.5) |

* Only top 11 diseases were listed.

GI: gastrointestinal.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of GI diseases, stratified by patient’s residency and disease group.

Figure 2.

The percentage of GI specialist care, stratified by patient’s residency and disease group.

Discussion

Main findings

Our current study of claims analysis revealed that rural residents in Taiwan were more likely to seek medical help for GI diseases than urban and suburban residents. Most rural people with GI problems would visit the non-GI clinics in rural areas. Urban patients were more likely than rural patients to consult gastroenterologists for hepatitis, esophageal disorder and gastroduodenal ulcer.

Interpretation of findings

The environmental factor might play a role. Although no concrete data had been officially published as to the hygiene situation in rural Taiwan, it was generally deemed that rural residents had less adequate sanitation in water supply and waste disposal. The poor hygiene in rural areas could be associated with infectious GI diseases [18,19].

The lifestyle of rural residents might differ from that of urban residents. For example, rural residents may have higher rates of adult smoking, physical inactivity, and alcohol abuse [20]. Besides, the aging population structure of rural areas could contribute to a higher prevalence of GI diseases. In the USA, a significant number of retirees moved into rural areas and young adults migrated to big cities for job or school, making the population structure of rural America older [21]. Such a phenomenon also existed in Taiwan [22]. The co-morbidities, polypharmacy and possible more drug-drug interactions in the elderly could make this population more vulnerable to suffer from GI problems [23].

Rural residents in Taiwan sought more medical help for gastritis and duodenitis than urban residents. Gastritis and duodenitis might be related to Helicobacter pylori infection [24]. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Taiwan and China was reported to be higher in rural developing areas than in urban developed ones [25-28]. The transmission of Helicobacter pylori in rural areas was more complex and could occur through contaminated food, water or intensive contact between infants and non-parental caretakers [29].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) might play another role in the rural–urban divide of visits for GI diseases [24]. In Portugal, the amount of NSAID prescriptions in the ambulatory general practice had been reported to be higher among the elderly and in rural areas [30]. A similar condition might also exist in Taiwan. NSAID might thus cause more frequent occurrences of gastroduodenal ulcer in rural people, what could partly explain the fact that in our current study rural people had more visits for ulcer disease than urban people. However, Helicobacter pylori and NSAID-related gastritis and duodenitis usually occur in chronic course. It is uncertain if the course of gastritis or duodenitis was acute or chronic in our study. Further researches are needed in this field.

Although rural patients were more likely to seek medical help for GI disease, most of them chose the non-GI clinics in rural areas. In Taiwan, the diagnoses and management of some specific diseases rely on specialists, but the general management or follow-up post diagnosis could be made by general practitioners. Our result implied that the physicians other than gastroenterologists in rural areas were the main gatekeepers for rural patients when medical services for GI diseases were needed. However, rural physicians might have more barriers to access necessary medical knowledge than non-rural physicians [31]. Physicians in rural areas were also more likely to felt isolated, dissatisfied with job security and frustrated by a lack of cooperation among the major providers of health care [32]. Therefore, the well communication between general practitioners in rural areas and gastroenterologists would be more important than those in non-rural areas. To build an adequate referral system is essential in remote setting [33]. Furthermore, telemedicine would be a solution for bridging geographic access gaps to specialty care [34]. It has also been proposed that the arrangement of specialist outreach clinics in rural areas could increase the accessibility and effectiveness of specialist services and the integration with primary care services [35].

On the other hand, urban patients were more likely than rural patients to consult gastroenterologists for hepatitis, esophageal disorder and gastroduodenal ulcer. One of the causes might be related to regulations of health insurance reimbursement. According to the pharmaceutical benefit scheme of the National Health Insurance in Taiwan [36], proton pump inhibitors can only be prescribed for peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease proved by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. The majority of such procedures are usually performed by gastroenterologists. The prescription of anti-viral agents for viral hepatitis is also limited to gastroenterologists. Because of the higher availability of specialists in urban areas than in rural areas, urban people would be more likely to be diagnosed with above-mentioned diseases.

Limitations

There were some limitations in our current study. The diagnoses for analysis came from the administrative claims and might be tentative instead of final. Besides, the severity of diseases was hardly available. The reasons of seeking GI care across the rural–urban border could not be truly uncovered either. Some patients seeking a GI specialist at the medical center might be referred from the general practitioners. We couldn’t calculate how many patients were referred to medical centers in the NHIRD. This could cause some bias. However, a formal referral system does not exist in Taiwan. The patients can freely choose the physicians and facilities. Finally, the impact of rural–urban divide on population health was not analyzed. The techniques to identify the outcome of disease management might go beyond the scope of our current study.

Strengths and impact of the study

Our study was the first nationwide, population-based study to demonstrate the difference of medical seeking behavior between rural and urban patients with GI problems. For those valuable information contained in Taiwan’s NHIRD, to examine the rural–urban disparity of medical service utilization for GI diseases could contribute to the policy making in the future.

Conclusions

The rural–urban disparity in GI care actually existed in Taiwan and most rural patients sought medical help for GI problems at non-GI clinics. A well-established referral system, telemedicine and even the arrangement of GI specialist outreach clinics to integrate with primary care services in rural areas might help to reduce the geographic gaps for rural patients. Further studies are needed to discover the influence as well as more resolution for the rural–urban divide in GI care.

Abbreviations

GI: Gastrointestinal; NHIRD: National Health Insurance Research Database; LHID2005: Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005; CCS: Clinical Classifications Software.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YHL conceived and carried out the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. YHT and YCC participated in the design of the study and helped to interpret findings. MHL, LFC and SJH participated in the design of the study and helped to perform the statistical analysis. TJC participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Yi-Hsuan Lin, Email: yihsuan723@gmail.com.

Yen-Han Tseng, Email: yenhan213@hotmail.com.

Yi-Chun Chen, Email: ycchen1204@gmail.com.

Ming-Hwai Lin, Email: mhlin@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Li-Fang Chou, Email: lifang@nccu.edu.tw.

Tzeng-Ji Chen, Email: tjchen@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Shinn-Jang Hwang, Email: sjhwang@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Acknowledgements

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes. This work was funded by the National Science Council in Taiwan [NSC96-2416-H-004-007-MY2] and Taipei Veterans General Hospital [V101C-125, V101D-001-2].

References

- Schultz M, Davidson A, Donald S, Targonska B, Turnbull A, Weggery S, Livingstone V, Dockerty JD. Gastroenterology service in a teaching hospital in rural New Zealand, 1991–2003. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:583–590. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GC, Tuskey A, Dassopoulos T, Harris ML, Brant SR. Rising hospitalization rates for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States between 1998 and 2004. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1529–1535. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comay D, Marshall JK. Resource utilization for acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: the Ontario GI bleed study. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:677–682. doi: 10.1155/2002/156592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R. A behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services. Chicago: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83:1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MC, Lai MS. Pediatricians’ role in caring for preschool children in Taiwan under the national health insurance program. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:849–855. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LN, Bhattacharyya N. Regional and specialty variations in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1092–1097. doi: 10.1002/lary.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GC, LaVeist TA, Harris ML, Wang MH, Datta LW, Brant SR. Racial disparities in utilization of specialist care and medications in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2202–2208. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebely J, Bryant J, Hull P, Hopwood M, Lavis Y, Dore GJ, Treloar C. Factors associated with specialist assessment and treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in New South Wales, Australia. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e104–e116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa-Jimenez F, Montijano-Cabrera AM, Puente-Gutierrez JJ, Bernal-Blanco E, Moreno-Izarra J, Delgado-Moreno M. Referrals to a gastroenterology outpatient clinic: differences according to patients’ geographical origin. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28:546–550. doi: 10.1157/13080602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Yeh HY, Wu JC, Haschler I, Chen TJ, Wetter T. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: administrative health care database as study object in bibliometrics. Scientometrics. 2011;86:365–380. doi: 10.1007/s11192-010-0289-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Wu JC, Chen TJ, Wetter T. Publicly available databases accelerate academic production. BMJ. 2011;342:297–298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Insurance Research Database, Taiwan. http://w3.nhri.org.tw/nhird/en/Data_Subsets.html.

- Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- Liu CY, Hung YT, Chuang YL, Chen YJ, Weng WS, Liu JS, Liang KY. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manage. 2006;4:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- The Perl programming language. http://www.perl.org/

- Tandir S, Huseinagic S, Sivic S. Investigation of health effects of current levels of environmental sanitation and hygienic living conditions of rural population in the municipality of Zenica. Med Arh. 2010;64:240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumwine JK, Thompson J, Katua-Katua M, Mujwajuzi M, Johnstone N, Porras I. Diarrhoea and effects of different water sources, sanitation and hygiene behaviour in East Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:750–756. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner A, Helen Berry E, Nina G. In: Population Change and Rural Society. Volume 3. 1st edition. Kandel WA, Brown DL, editor. Netherlands: Springer; 2006. The changing faces of rural America; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen SM, Hsieh YS. A comparative study on aging between Taipei City and Taiwan’s rural areas. Ingu munje nonjip. 1996;17:31–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozymski EM, Isaacs KL. Special diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in elderly patients with upper gastrointestinal disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13(Suppl 2):S65–S75. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199112002-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borch K, Jonsson KA, Petersson F, Redeen S, Mardh S, Franzen LE. Prevalence of gastroduodenitis and Helicobacter pylori infection in a general population sample: relations to symptomatology and life-style. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1322–1329. doi: 10.1023/A:1005547802121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LM, Thomas TL, Ma JL, Chang YS, You WC, Liu WD, Zhang L, Pee D, Gail MH. Helicobacter pylori infection in rural China: demographic, lifestyle and environmental factors. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:638–645. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Hu F, Zhang L, Yang G, Ma J, Hu J, Wang W, Gao W, Dong X. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and identification of risk factors in rural and urban Beijing, China. Helicobacter. 2009;14:128–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LK, Hwang SJ, Wu TC, Chu CH, Shaw CK. Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus infection in school-aged children on two isolated neighborhood islands in Taiwan. Helicobacter. 2003;8:168–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Chuang CK, Lee HC, Chiu NC, Lin SP, Yeung CY. A seroepidemiologic study of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus infection in primary school students in Taipei. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005;38:176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale FF, Vítor JM. Transmission pathway of Helicobacter pylori: does food play a role in rural and urban areas. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;138:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago LM, Marques M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions in the ambulatory of general practice in the centre of Portugal. Acta Reumatol Port. 2007;32:263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro DM, D’Alessandro MP, Galvin JR, Kash JB, Wakefield DS, Erkonen WE. Barriers to rural physician use of a digital health sciences library. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998;86:583–593. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte SJ, Imershein AW, Magill MK. Rural community and physician perspectives on resource factors affecting physician retention. J Rural Health. 1992;8:185–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1992.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjessing K, Faresjö T. Exploring factors that affect hospital referral in rural settings: a case study from Norway. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9:975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AB, Probst JC, Shah K, Chen Z, Garr D. Differences in readiness between rural hospitals and primary care providers for telemedicine adoption and implementation: findings from a statewide telemedicine survey. J Rural Health. 2012;28:8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruen RL, Weeramanthri TS, Knight SE, Bailie RS. Specialist outreach clinics in primary care and rural hospital settings. Community Eye Health. 2006;19:31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The pharmaceutical benefit scheme of the National Health Insurance in Taiwan. http://www.nhi.gov.tw/