Abstract

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are at increased risk of bacterial cholangitis due to biliary strictures and bile stasis. A subset of PSC patients suffer from repeated episodes of bacterial cholangitis, leading to frequent hospitalizations and impaired quality of life. Although PSC waitlist candidates with bacterial cholangitis frequently receive exception points, and/or are referred for living donor transplantation, the impact of bacterial cholangitis on waitlist mortality is unknown. We performed a retrospective cohort study of all adult PSC waitlist candidates listed for initial transplantation from February 27, 2002 to June 1, 2012 at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Colorado-Denver. Over this period, 171 PSC patients were waitlisted for initial transplantation. Prior to waitlisting, 38.6% (66/171) of patients had a history of bacterial cholangitis, while 28.0% (44/157) of those with at least one MELD update experienced cholangitis on the waitlist. During follow-up, 30 (17.5%) patients were removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration, with 46.7% (14/30) developing cholangiocarcinoma. Overall, 12/82 (14.6%) waitlist candidates who ever had an episode of cholangitis were removed for death or clinical deterioration, compared with 18/89 (20.2%) without cholangitis (P=0.34 comparing two groups). No patients were removed due to bacterial cholangitis. In multivariable competing risk models, a history of bacterial cholangitis was not associated with an increased risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration (subhazard ratio=0.67; 95% CI: 0.65-0.70, P<0.001). In summary, PSC waitlist transplant candidates with bacterial cholangitis do not have an increased risk of waitlist mortality. The data call into question the systematic granting of exception points or referral for living donor transplantation due to a perceived risk of increased waitlist mortality.

Keywords: Primary sclerosing cholangitis, bacterial cholangitis, exception points, cholangiocarcinoma, waitlist mortality

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic cholestatic disorder characterized by progressive biliary strictures, ultimately leading to the development of liver failure or cholangiocarcinoma. As a result of biliary strictures and bile stasis, patients with PSC are at increased risk of bacterial cholangitis. Among PSC patients, bacterial cholangitis is more commonly seen in those with a history of biliary tract instrumentation (i.e. endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ERCP) and/or dominant bile duct strictures.(1) Further, bacterial cholangitis may be associated with secondary complications, including endocarditis and hepatic abscess formation.(2) A subset (<10%) of patients with PSC will suffer from repeated bouts of bacterial cholangitis, which may result in frequent hospitalizations and thus impaired quality of life.(3) PSC is clearly associated with a considerable amount of morbidity, however the impact of bacterial cholangitis on mortality of patients with PSC is unknown.(4)

Among patients waitlisted for liver transplantation, prioritization on the waitlist is determined by a patient's Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. The MELD score, calculated based on a patient's INR, bilirubin, and creatinine, does not account for complications of liver disease. As a result, waitlist candidates with PSC, and specifically those suffering from bacterial cholangitis, are frequently referred for living donor liver transplantation and/or receive MELD exception points after petition to a regional review board (RRB).(5, 6) This is despite evidence that even after accounting for exception points, MELD score, and differences in living donor liver transplantation, waitlist candidates with PSC have a lower risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration when compared to candidates with other forms of end-stage liver disease.(7) Additionally, there is no data evaluating whether waitlist candidates with PSC who suffer from episodes of bacterial cholangitis have an increased risk of mortality.(4, 5) While there are published recommendations to guide RRBs on which patients with PSC and recurrent bacterial cholangitis should receive exception points, these are not evidence-based.(2)

National transplant registry data available from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) do not capture data on episodes of bacterial cholangitis, which limits the ability to evaluate its association with waitlist mortality. Accordingly, using patient-level data from two large liver transplant centers, we sought to determine whether: a) waitlist transplant candidates with PSC and bacterial cholangitis have an increased risk of waitlist mortality; and b) whether or not current practices of allocation of exception points for patients with PSC and bacterial cholangitis are justified.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all adult (≥18 years of age) waitlist transplant candidates diagnosed with PSC at the University of Pennsylvania (UP) and the University of Colorado-Denver (UCD) between February 27, 2002 and June 1, 2012. At each center, the respective transplant databases were queried to identify waitlist candidates with a diagnosis of PSC. The diagnosis of PSC was confirmed based on the constellation of clinical, biochemical, radiologic, and histologic features, consistent with published guidelines.(1)

All PSC patients waitlisted for an initial transplant on or after February 27th, 2002 were included. The start date was chosen to limit the analysis to the MELD era. We excluded patients listed for re-transplantation.

For each study subject, a detailed medical record review was conducted at each center (D.G., A.C., and A.M-C.). Relevant demographic and clinical information were recorded from the chart, including age, self-reported race, gender, date of diagnosis of PSC, history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; defined by review of medical endoscopy or pathology reports, and/or documentation of medical record of confirmatory endoscopy and pathology consistent with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease), laboratory data, and presence/absence of cirrhosis on radiographic imaging.

Subjects were defined as having cirrhosis if a liver biopsy, and/or a radiographic study (ultrasound, CT, or MRI) had findings consistent with cirrhosis (including a nodular contour of the liver surface and/or caudate lobe hypertrophy). Detailed data on waitlist removal were obtained, including the reason for removal (based on UNOS coding criteria), and the specific cause of death and/or clinical deterioration for those removed from the waitlist because of death, or being deemed too sick or medically unsuitable for transplantation.

Given the complexity of the diagnosis of bacterial cholangitis in the setting of PSC, we chose to define an episode of cholangitis based on any physician medical record documentation stating the patient had an episode of bacterial cholangitis. We did not use elevated alkaline phosphatase levels and/or jaundice, or MRICP/ERCP abnormalities to further define cholangitis episodes as patients with PSC commonly have baseline abnormalities in one of these parameters.(8) As a result, we defined bacterial cholangitis as any physician medical record documentation stating the patient had an episode of bacterial cholangitis. While these episodes were commonly associated with fever, right upper quadrant pain, worsened jaundice, and/or bacteremia in the absence of an alternative source of infection, there were no specific criteria used given the retrospective nature of the study.

Outcome

The primary outcome was waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration, defined as the patient being deemed too sick or medically unsuitable for transplantation. Outcomes were initially determined by review of the transplant databases at the respective transplant centers, but all waitlist removals were subsequently confirmed by detailed medical record review to verify accuracy of the transplant databases.

Statistical analysis

We used Fisher's exact test and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables and Student t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables (according to their distributions) to compare waitlist candidates with vs. without bacterial cholangitis and those who were vs. were not removed for death or clinical deterioration.

In evaluating whether bacterial cholangitis impacts the risk of waitlist mortality, one must consider the competing risk of transplantation, as it influences the probability that a waitlist candidate will be removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration.(9) Thus we fit competing risk Cox regression models, with waitlist removal as the outcome, and transplantation as the competing risk.(9-11) All other outcomes were treated as censors. Waitlist candidates still on the waitlist at the end of follow-up were censored on that date.

The primary covariate of interest was history of bacterial cholangitis prior to or while on the waitlist. We grouped together all episodes of bacterial cholangitis as the objective of the study was to determine if cholangitis, regardless of timing, was associated with worsened outcomes. In addition, a history of cholangitis, regardless of timing, is commonly used as a criterion for granting of exception points. Secondary models were used to evaluate the association between waitlist mortality and a history of bacterial cholangitis prior to listing or while on the waitlist separately.

Potential covariates included were gender, race (white vs. non-white due to sparse sample sizes of non-white patients), age at listing, MELD score at listing, and history of a portal hypertensive complications (ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) prior to listing. Covariates were first tested in single-item fashion; we included any variable with a p-value ≤0.2 in the final model. The final models used a stepwise variable-selection process to retain variables with p-values ≤0.1. Potential confounders were included if the variable changed the hazard ratio of bacterial cholangitis by 10%. We used robust standard errors to account for correlation due to patient clustering by transplant center.(12) Covariates were reported as subhazard ratios, given the use of competing risk models.(9, 11)

Competing risk survival curves comparing the risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration, accounting for the competing risk of transplantation, were constructed using the “stcurve” function in Stata.

We chose to exclude the small number of patients with missing data from the final multivariable models (N=10) given the limited variables that could be used for multiple imputation.

Institutional Review Board Approval was obtained from both the UP and the UCD. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

From February 27th, 2002 to June 1st, 2012, 171 patients with PSC were listed for initial transplantation at the UP (83) and the UCD (88). The median age was 48 years (interquartile range (IQR): 37-58), with PSC waitlist candidates being predominantly white (83.6%; 143/171) and male (73.1%; 125/171).

At the time of listing, 76.6% (131/171) had a documented history of IBD, with a significantly greater proportion of waitlist candidates at the UP with IBD (85.5% vs. 68.2%; P=0.007; Table 1). Of those with IBD, nearly 80% (79.4%, 104/131) had ulcerative colitis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, clinical and laboratory data at the time of listing, N=171

| Variable | University of Pennsylvania, =83 | University of Colorado-Denver, N=88 | Combined two center data | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age at listing, years (IQR) | 48 (32, 58) | 38 (37, 58) | 48 (37-58) | 0.98 |

| Race, N (%) | 0.44* | |||

| White | 67 (80.7) | 76 (86.4) | 143 (83.6) | |

| Black | 14 (16.9) | 8 (9.1) | 22 (12.9) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Other | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Male gender, N (%) | 57 (69.5) | 68 (77.3) | 125 (73.1) | 0.25 |

| History of IBD, N (%) | 71 (85.5) | 60 (68.2) | 131 (76.6)† | 0.007 |

| IBD subtype, N (%) | 0.49† | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 57 (80.3) | 47 (78.3) | 104 (79.4) | |

| Crohn's | 13 (18.3) | 10 (16.7) | 23 (17.6) | |

| Indeterminate | 1 (1.4) | 3 (5.0) | 4 (3.1) | |

| INR | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) | 1.14 (1.0, 1.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4)‡ | 0.008 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 3.6 (1.9, 10.6) | 2.3 (1.1, 8.2) | 3.3 (1.4-10.1) | 0.06 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 0.14 |

| Laboratory MELD score | 15 (10, 20) | 12 (7, 17) | 14 (9-19)** | 0.01 |

| AST, U/L | 110 (73, 161) | 85.5 (53, 126) | 98 (63-156)†† | 0.01 |

| Platelet count (thousand/μl) | 173 (101, 238) | 180 (121, 287) | 178 (110-281) | 0.13 |

| Variceal bleeding, N (%) | 18 (21.7) | 10 (11.4) | 28 (16.4) | 0.07 |

| SBP, N (%) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0.97 |

| Ascites, N (%) | 31 (37.4) | 23 (26.1) | 54 (31.6) | 0.12 |

| Encephalopathy, N (%) | 14 (16.9) | 12 (13.6) | 26 (15.2) | 0.56 |

| Radiographic evidence of cirrhosis, N (%) | 51 (61.5) | 41 (46.6) | 92 (53.8) | 0.08 |

P-value compares the values at the two centers, or the distribution across the two centers for race and IBD subtype

Listing laboratory and clinical data

The median laboratory MELD score at the time of listing was 14 (IQR: 9-19), with waitlist candidates at the UP having significantly higher laboratory MELD scores at listing (15 [IQR 10-20] vs. 12 [IQR 7-17]; P=0.008). The median listing serum creatinine was 0.8mg/dL (IQR: 0.7-1.0), total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL (IQR: 1.4-10.1), and INR 1.2 (IQR: 1.1-1.4; Table 1).

Prior to waitlisting, 39.2% (67/171) of waitlist candidates had experienced a hepatic decompensation (Table 1), with 31.6% (54/171) having ascites, 16.4% (28/171) with variceal bleeding, 15.2% (26/171) with hepatic encephalopathy, and 1.1% (2/171) with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Based on imaging prior to waitlisting (as few patients had liver biopsy due to it not being needed for the diagnosis of PSC, the data on radiographic diagnosis is presented), 53.8% (92/171) of waitlist PSC candidates had documented cirrhosis. None of these variables differed by center.

Episodes of bacterial cholangitis

Prior to waitlisting, 38.6% (66/171) of waitlist candidates had a reported history of bacterial cholangitis. A similar proportion of waitlist candidates experienced at least one episode of bacterial cholangitis across the two centers (Table 2a). At each center, over 50% of waitlist candidates experienced greater than one episode of bacterial cholangitis prior to waitlisting (median number of episodes could not be calculated as discrete number of episodes not available for every patient).

Table 2.

Listing and waitlist data on cholangitis of waitlist candidates with PSC

| a) Bacterial cholangitis prior to listing, N=171* | |

|---|---|

| Bacterial cholangitis prior to listing, N (%) | 66 (38.6) |

| Number of episodes cholangitis, N (%) | |

| 1 | 30 (45.5) |

| 2 | 11 (16.7) |

| 3-6 | 9 (13.4) |

| Multiple or several† | 16 (24.2) |

| b) Bacterial cholangitis while on waitlist, N=157* | |

|---|---|

| Bacterial cholangitis while on waitlist, N (%) | 44 (28.0)† |

| Number of episodes of cholangitis, N (%) | |

| 1 | 26 (59.1) |

| 2 | 9 (20.4) |

| 3-6 | 5 (11.4) |

| Multiple or several‡ | 4 (9.1) |

Similar proportions (P=0.52) of patients had bacterial cholangitis prior to listing between two centers

Multiple or several chosen when medical record specified greater than one episode of bacterial cholangitis without the exact number

10 patients removed from waitlist at the University of Pennsylvania prior to having any waitlist MELD updates or interval waitlist data prior to removal. 4 patients with missing data on history of cholangitis while on the waitlist from the University of Colorado-Denver

P=0.003 comparing proportion of patients with bacterial cholangitis on waitlist (University of Pennsylvania: 16.4% (12/71) vs. University of Colorado-Denver: 38.1% (32/84)

Multiple or several chosen when medical record specified greater than one episode of bacterial cholangitis without the exact number

Among waitlist candidates with at least one UNOS MELD update while waitlisted, 28.0% (44/157) had an episode of bacterial cholangitis after listing, with a significantly greater proportion of waitlist candidates at the UCD suffering from bacterial cholangitis (Table 2b).

Overall, 48.0% (82/171) of waitlisted PSC candidates experience at least one episode of bacterial cholangitis prior to waitlisting and/or while on the waitlist. A significantly greater proportion of waitlist candidates from the UCD had cholangitis at any point in time (59.8% [49/88] vs. 40.2% [33/83]; P=0.04).

Waitlist outcomes

Table 3 displays the reasons for waitlist removal for PSC candidates from the two centers. Median time on the waitlist was similar between the two centers (data not shown). Waitlist time was also similar for those with a history of cholangitis vs. those without.

Table 3.

Reasons for waitlist removal, N=150*

| Deceased donor OLT, N (%) | 67 (44.7) |

| LDLT, N (%) | 18 (12.0) |

| Died, N (%) | 16 (10.7)† |

| Medically unsuitable or too sick to transplant, N (%) | 14 (9.3)‡ |

| Other, N (%) | 35 (23.3) |

| Lost to follow-up | 12 (8.0) |

| Transferred to another center | 4 (2.7) |

| Patient request | 1 (0.7) |

| Transplanted at another center | 8 (5.3) |

| Other | 10 (6.7) |

12 and 9 patients remained listed at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Colorado-Denver at the end of follow-up, respectively

Cholangiocarcinoma (5), bleeding peptic ulcer (2), pneumonia (2), variceal bleed, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, fungemia, hepatorenal syndrome, small bowel obstruction, hemorrhagic stroke, intra-abdominal bleed during interventional radiology procedure

**Cholangiocarcinoma (9), progressive wasting, sepsis of unknown source, too ill without specification, pancreatic cancer, complications post-coronary artery bypass surgery

At the end of follow-up, 12.3% (21/171) of PSC waitlist candidates listed since 2/27/02 were still listed. During follow-up, 49.7% (85/171) were transplanted at one of the two centers, with 21.2% (18/85) living donor liver recipients. An additional 8 (4.7%) patients listed at the UP were transplanted at another center. There was a non-significant increase in the odds of receiving a decreased donor transplant among those with versus without a history of cholangitis (35 [49.3%] versus 32 [39.0%]; P=0.20).

During follow-up, there were 13 waitlist candidates transplanted with exception points (9 at UC-D and 4 at UP): cholangiocarcinoma (7), recurrent cholangitis (3), hepatocellular carcinoma (1), fatigue, bone disease, and failure to thrive (1), colon dysplasia requiring colectomy in a decompensated cirrhotic (1).

Thirty waitlist candidates (17.5%) were removed from waitlist for death or clinical deterioration, with 53.3% (16/30) of those dying while still waitlisted, and the remaining 46.7% (14/30) removed for clinical deterioration. None of these 30 patients had bacterial cholangitis immediately preceding delisting or as the inciting event for death or delisting.

Causes of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration are listed in Table 3. Notably, 46.7% (14/30) had biopsy proven or presumed (based on imaging or atypical cells on ERCP brushings) cholangiocarcinoma as the cause of removal for death or clinical deterioration. Only 16.7% (5/30) were removed due to an infection/sepsis, and none were cholangitis-related.

Among those who received a deceased donor liver transplant, the median MELD of those with a history of cholangitis was 22 (IQR 15-26), compared with 25 (IQR 20-28) in those without cholangitis (P=0.12). Among those who were removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration, those with a history of cholangitis had a median MELD score of 27 (IQR 11-31), as compared with 26 (IQR 18-36) in those without cholangitis (P=0.74).

Waitlist time was significantly longer for those who were removed for death or clinical deterioration (median 341 days; IQR 107-1064) vs. those transplanted (median 151 days; IQR 41-492; P=0.01). At the time of removal, those who died or clinically deteriorated had numerically, but not statistically significantly, higher laboratory MELD scores compared with those who were transplanted (median 26; IQR 18-33 vs. median 21; IQR 16-26; P=0.06).

During follow-up, 14.6% (25/171) waitlist candidates developed cholangiocarcinoma. Of these 25, 44% (11/25) were transplanted, while the other 56% were removed for death or clinical deterioration. The risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma did not differ based on a history of bacterial cholangitis (18.3% [15/82] with cholangitis developed cholangiocarcinoma vs. 11.2% [10/89] without cholangitis; P=0.19).

Outcomes based on history of cholangitis

We compared the crude risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration based on: a) history of cholangitis prior to listing; b) cholangitis while on the waitlist; and c) cholangitis prior to waitlisting and/or on the waitlist. Within each group, the risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration was similar when stratified by center (data not shown).

Among the 66 waitlist candidates with bacterial cholangitis prior to listing, 18.2% (12/66) were removed for death or clinical deterioration, compared with 17.1% (18/105; P=0.86 comparing two groups) without cholangitis prior to listing.

Among the 44 waitlist candidates with bacterial cholangitis after listing, 9.1% (4/44) were removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration, compared with 21.2% (24/113; P=0.07 comparing groups) without cholangitis (157 total waitlist candidates with at least 1 MELD update).

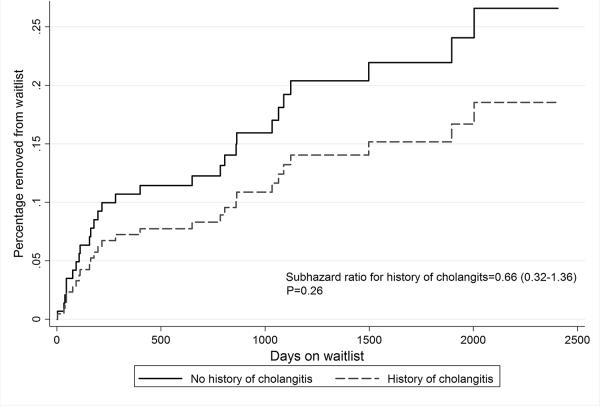

Overall, of 82 waitlist candidates who ever had an episode of cholangitis, 14.6% (12/82) were removed for death or clinical deterioration, compared with 20.2% (18/89) of those without a history of cholangitis (P=0.34 comparing two groups). Similar unadjusted results were obtained in time-dependent competing risk analyses (competing risk survival curves; P=0.26; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Competing risk regression evaluating risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration

Waitlist candidates with a history of cholangitis at any point in time were numerically more likely to be transplanted during follow-up (59.8% [49/82] vs. 49.4% [44/89]), however this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.18). Similar results were obtained excluding the 8 patients transplanted at another center.

In univariable competing risk Cox regression models, a history of cholangitis prior to and/or on the waitlist and male gender were associated with a decreased hazard of removal for death or clinical deterioration, while white race, older age, and higher laboratory MELD score at listing were associated with an increased hazard (Table 4; history of hepatic decompensation was non-significant and excluded from final model). In multivariable competing risk models, a history of cholangitis was associated with a significantly decreased hazard of removal for death or clinical deterioration (subhazard ratio [SHR]=0.67, 95% CI: 0.65-70, P<0.001), while white race and increased age were associated with an increased risk.

Table 4.

Competing risk Cox regression models evaluating risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration associated with bacterial cholangitis

| Variable | Univariable subhazard ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable subhazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholangitis ever | 0.66 (0.53, 0.84) | 0.67 (0.65, 0.70) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 0.90 (0.85, 0.96) | 0.84 (0.61, 1.16) | 0.29 |

| White race | 1.88 (1.67, 2.12) | 2.11 (1.83, 2.43) | <0.001 |

| Listing laboratory MELD score* | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.18 |

| Age at listing† | 1.35 (1.02, 1.80) | 1.37 (1.05, 1.79) | 0.02 |

Increments of 1 MELD point

Five year increments

In multivariable competing risk Cox models evaluating each of the bacterial cholangitis covariates separately, a history of cholangitis prior to waitlisting was not associated with an increased risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration (SHR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.60-1.66; P=0.99), while cholangitis on the waitlist was associated with a decreased risk (SHR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.16-0.93; P=0.03).

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate the risk of waitlist mortality associated with bacterial cholangitis in waitlisted patients with PSC, using 10 years of data from two large transplant centers. During a ten year period, nearly half of waitlist candidates with PSC experienced at least one episode of bacterial cholangitis. A history of bacterial cholangitis was not associated with an increased risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration. Most importantly, of the 30 patients removed for death or clinical deterioration, none had known cholangitis as the inciting event. The data call into question the prevailing belief that PSC patients with bacterial cholangitis are at increased risk of waitlist mortality, and thus merit exception points and/or referral for living donor transplantation based solely on the risk of waitlist mortality.

PSC is a progressive disease that has a significant impact on patient morbidity and mortality. Early natural history studies demonstrated that nearly 75% of PSC patients were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis.(13) Median survival from the time of diagnosis was 11.9 years.(13) With earlier diagnosis due to increased awareness of the disease, availability of noninvasive imaging of the biliary tree, increased use of routine liver enzyme evaluation in asymptomatic patients, and recognition of the association between IBD and PSC, more asymptomatic cases are detected.(8) Despite this, a significant burden of disease remains, with approximately 5% of all liver transplants, and 14% of living donor liver transplants being performed in patients with PSC.(6, 7)

Using UNOS data on all waitlist transplant candidates, we have previously shown that 13.6% of waitlisted candidates with PSC from 2002-2009 were removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration.(7) This data though does not allow for evaluation of bacterial cholangitis in waitlist candidates, necessitating the analysis of patient-level data.

The data presented here demonstrate that in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, bacterial cholangitis in PSC waitlist candidates was not associated with an increased risk of mortality or clinical deterioration. This is underscored by the fact that the causes of death or clinical deterioration were due to cholangiocarcinoma, portal hypertension, non-cholangitis sepsis, or other non-hepatic conditions, but not bacterial cholangitis. This data echo early PSC data from the Mayo Clinic's series from the 1970s. Of 39 PSC patients followed prospectively, 13 (33.3%) died, with 11/13 deaths from liver failure, one due to cholangiocarcinoma, and one as a complication of colon cancer. Similar to our data, no deaths were directly related to bacterial cholangitis.(3) More recent data from Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, demonstrated that among 255 waitlisted PSC patients followed over an 11 year period, 32 (12.5%) were removed for death or clinical deterioration. None of the waitlist removals were related to bacterial cholangitis.(14) Our analysis, the first to specifically evaluate the association between bacterial cholangitis and mortality, validates these earlier studies.

Although the risk of cholangiocarcinoma in our series is higher than previously published Scandinavian data (14), when accounting for tumors diagnosed on explant or during the transplant operation(15), the risk of cholangiocarcinoma in our cohort was not substantially greater than previously reported. The higher rate of cholangiocarcinoma on the waitlist seen in our cohort may be related to improved non-invasive imaging techniques (MRI, MRCP) when compared to the Scandinavian data from 1990-2000, and/or the increased waiting times in the United States, which may result in an increased risk of developing and/or detecting cholangiocarcinoma. While there is no specific protocol for surveillance of cholangiocarcinoma at each center, clinicians typically obtain yearly CT or MRI scans, along with CA-19-9 tests, or more frequently if clinically indicated. All of the transplants for cholangiocarcinoma with exception points were at the University of Colorado which follows the Mayo cholangiocarcinoma transplantation protocol.(16)

An additional notable finding is that infections were rarely a direct cause of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration, unlike what is seen in patients with other forms of end-stage liver disease.(17) One potential explanation for this is that at least based on radiologic imaging pre-waitlisting, a substantial proportion of our patients did not have radiographic evidence of cirrhosis. Although MRI and CT scans are not 100% sensitive or specific for this diagnosis, the data suggest that PSC patients waitlisted for transplantation may not all have cirrhosis, which may explain the different waitlist risk profile seen in this patient population.(7)

The issue of the risk of mortality associated with bacterial cholangitis in PSC patients, and its impact on organ allocation, is important given the limited supply of transplantable organs. Due to a concern that patients with PSC and bacterial cholangitis potentially have an increased risk of waitlist mortality, transplant centers frequently apply for exception points for these patients. In fact, since February 27th, 2002, 337 PSC patients have applied for MELD exception points for bacterial cholangitis, with the vast majority of these patients being granted exception points, and ultimately transplanted, despite nearly three-fourths of them not meeting published recommendations for exception points for PSC and bacterial cholangitis.(5) Additionally, PSC waitlist candidates are significantly more likely to receive a living donor transplant, compared to patients with other forms of end-stage liver disease, with recurrent cholangitis frequently being the indication.(6) While our data does not speak to the utility or necessity of transplantation due to morbidity and impaired quality of life related to bacterial cholangitis, it does demonstrate that bacterial cholangitis alone is not associated with increased mortality.

Given the non-significant differences in the odds of transplantation in those with versus without a history of cholangitis, the decreased risk of mortality in patients with a history of cholangitis is not solely due to an increased rate of transplantation in this cohort, either through exception points, living donor transplantation, and or increased MELD scores, and thus increased prioritization for deceased donor organs. Further, the MELD scores at transplantation and removal were not different in those with versus without cholangitis, suggesting that cholangitis alone does not result in a significantly increased MELD score that would change waitlist outcomes.

Our observations had several limitations. We combined data from two transplant centers for this analysis. The sample size for this study was small, and only included 171 waitlist candidates with PSC. The two centers are situated in UNOS regions with above average MELD scores at transplantation, therefore the data may not be generalizable to all waitlist candidates with PSC in all UNOS regions. The data was retrospective in nature, and we were reliant on accurate documentation in the medical record for our data. Further prospective, multi-center data is needed to confirm our findings. The demographic distribution of PSC candidates at the two centers was similar. Although patients at the UP were more likely to have a history of IBD prior to listing, this should not account for our findings. The laboratory MELD scores at listing at the UP were slightly higher, however we adjusted for MELD score in our final models. The distribution of portal hypertensive complications was similar though. We did note that a significantly greater proportion of waitlist candidates at the UCD had cholangitis on the waitlist. While the reason for this is unclear, perhaps due to provider differences in the use of prophylactic antibiotics, the risk of adverse waitlist outcomes did not differ at each center, thus this was not a substantial limitation.

The definition of cholangitis was based on physician documentation in the medical record, without definitive corroborating bacteremia or ERCP procedure documentation. We chose to define cholangitis using physician documentation that is based on expert opinion and clinical judgment for several reasons. The diagnosis of bacterial cholangitis is difficult in the setting of PSC. Traditional laboratory abnormalities such as hyperbilirubinemia and elevated alkaline phosphatase are common at baseline in these patients. Secondly, findings such as worsening jaundice, fever, and/or right upper quadrant pain or tenderness, in the absence of another infection, may signify bacterial or non-bacterial cholangitis in this patient population, and retrospectively defining an episode of bacterial cholangitis requires use of prior clinician opinion of treating physicians. Lastly, even with data on blood cultures or ERCP procedure reports (when performed in the setting of a dominant stricture), there is no single finding that is confirmatory for bacterial cholangitis in PSC, and the diagnosis (or presumed diagnosis) is reliant on clinician judgment). Although misclassification may exist, such that patients were misclassified as cholangitis in the absence of such an infection, we would not expect this to change our results. Among those categorized as bacterial cholangitis, only if a significantly greater proportion of those who did not die were misclassified (leading to an underestimation of the risk of mortality from cholangitis) would we expect our results to show an increased risk of mortality in patients with cholangitis, which is extremely unlikely. Additionally, this difficulty in definitively diagnosing cholangitis in this population also speaks to the challenge of granting exception points or using this as a basis for increased prioritization. It may in fact be that only those patients with bacteremia and/or septic complications are at greater risk of mortality, which not only supports the published consensus recommendations for exception points in PSC, but also forces us to more stringently define cholangitis in this population to better treat and risk stratify PSC patients. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, we could not specifically determine which episodes of cholangitis were associated with bacteremia, with or without sepsis. However, as no waitlist removals for death or clinical deterioration were directly due to cholangitis, this suggests that even among the subset of patients with cholangitis complicated by bacteremia, the risk of waitlist mortality may not be significantly increased. Further multi-center prospective data is needed though to confirm this.

We were missing data on 10 patients, and excluded them from the final multivariable model. However, as the univariable and multivariable hazard ratios were similar, and the hazard ratio was significantly less than 1, this should not have impacted our results. Thirdly, waitlist candidates with bacterial cholangitis may have received a living donor liver transplant and/or received MELD exception points to decrease their probability of dying on the waitlist, thus increasing the likelihood of transplantation. However, as shown, only 10% of PSC waitlist candidates received a living donor transplant and 9% received exception points. Of living donor recipients, only 11/18 had a history of cholangitis, while only 3/13 transplant recipients with MELD exception points were granted exceptions for recurrent cholangitis. This demonstrates that referral of PSC waitlist candidates with cholangitis for living donor transplantation and/or MELD exception points do not explain the findings. Even under a worst-case scenario whereby all living donor recipients and exception point recipients died, the outcomes of patients with cholangitis would be the same as non-cholangitis patients, but not worse. We defined cirrhosis based on radiographic imaging, as few patients had liver biopsies, is not 100% sensitive. Despite this, given the substantial number of patients without radiographic evidence of cirrhosis, it is still likely that a sizable proportion of the patients did not in fact have cirrhosis. Lastly, we were unable to accurately determine if patients were on suppressive antibiotic therapy due to a history of recurrent cholangitis. Although this may have decreased the risk of complications from cholangitis and/or prevented the development of non-cholangitis complications, this is unlikely to fully account for our results.

In summary, we have shown that waitlisted transplant candidates with PSC and bacterial cholangitis do not have an increased risk of waitlist mortality when compared with those without cholangitis. Over a 10 year period, no patients died on the waitlist or were removed for clinical deterioration as a result of bacterial cholangitis. The data calls into question the systematic granting of exception points for patients with PSC and bacterial cholangitis on the basis of increased waitlist mortality. Multi-center patient level data is needed to validate these findings and develop predictors of waitlist mortality to better risk stratify PSC waitlist candidates in greatest need of exception points and pre-emptive living donor transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Grants and Financial Support: NIH/NIDDK F32 1-F32-DK-089694–01 Grant (D.G.)

Abbreviations

- PSC

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- ERCP

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- RRB

Regional review board

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- UP

University of Pennsylvania

- UCD

University of Colorado-Denver

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IQR

Interquartile range

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report as it pertains to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, Nagorney DM, Boberg KM, Shneider B, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):660–78. doi: 10.1002/hep.23294. Epub 2010/01/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gores GJ, Gish RG, Shrestha R, Wiesner RH. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception for bacterial cholangitis. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(12 Suppl 3):S91–2. doi: 10.1002/lt.20966. Epub 2006/11/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiesner RH, LaRusso NF. Clinicopathologic features of the syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1980;79(2):200–6. Epub 1980/08/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman RB, Jr., Gish RG, Harper A, Davis GL, Vierling J, Lieblein L, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception guidelines: results and recommendations from the MELD Exception Study Group and Conference (MESSAGE) for the approval of patients who need liver transplantation with diseases not considered by the standard MELD formula. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(12 Suppl 3):S128–36. doi: 10.1002/lt.20979. Epub 2006/11/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg D, Bittermann T, Makar G. Lack of Standardization in Exception Points for Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Bacterial Cholangitis. Am J Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03969.x. Epub 2012/02/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg DS, French B, Thomasson A, Reddy KR, Halpern SD. Current trends in living donor liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Transplantation. 2011;91(10):1148–52. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821694b3. Epub 2011/05/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg D, French B, Thomasson A, Reddy KR, Halpern SD. Waitlist survival of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis in the model for end-stage liver disease era. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(11):1355–63. doi: 10.1002/lt.22396. Epub 2011/08/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy C, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: epidemiology, natural history, and prognosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26(1):22–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933560. Epub 2006/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim WR, Therneau TM, Benson JT, Kremers WK, Rosen CB, Gores GJ, et al. Deaths on the liver transplant waiting list: an analysis of competing risks. Hepatology. 2006;43(2):345–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.21025. Epub 2006/01/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satagopan JM, Ben-Porat L, Berwick M, Robson M, Kutler D, Auerbach AD. A note on competing risks in survival data analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(7):1229–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602102. Epub 2004/08/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 12.French B, Heagerty PJ. Analysis of longitudinal data to evaluate a policy change. Stat Med. 2008;27(24):5005–25. doi: 10.1002/sim.3340. Epub 2008/07/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiesner RH, Grambsch PM, Dickson ER, Ludwig J, MacCarty RL, Hunter EB, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: natural history, prognostic factors and survival analysis. Hepatology. 1989;10(4):430–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100406. Epub 1989/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandsaeter B, Broome U, Isoniemi H, Friman S, Hansen B, Schrumpf E, et al. Liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis in the Nordic countries: outcome after acceptance to the waiting list. Liver Transpl. 2003;9(9):961–9. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50169. Epub 2003/08/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandsaeter B, Isoniemi H, Broome U, Olausson M, Backman L, Hansen B, et al. Liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis; predictors and consequences of hepatobiliary malignancy. J Hepatol. 2004;40(5):815–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.002. Epub 2004/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darwish Murad S, Kim WR, Harnois DM, Douglas DD, Burton J, Kulik LM, et al. Efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiation, followed by liver transplantation, for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma at 12 US centers. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):88–98. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.008. quiz e14. Epub 2012/04/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajaj JS, O'Leary JG, Reddy KR, Wong F, Olson JC, Subramanian RM, et al. Second infections independently increase mortality in hospitalized cirrhotic patients: The nacseld experience. Hepatology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hep.25947. Epub 2012/07/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]