Abstract

BACKGROUND

Ureaplasma respiratory tract colonization is a risk factor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in preterm infants, but whether Ureaplasma isolates from colonized infants can form biofilms is unknown. We hypothesized that Ureaplasma isolates vary in capacity to form biofilms that contribute to their antibiotic resistance and ability to evade host immune responses. Study objectives were to 1) determine the ability of Ureaplasma isolates from preterm neonates to form biofilms in vitro; 2) compare the susceptibility of the sessile and planktonic organisms to azithromycin and erythromycin; and 3) determine the relationship of biofilm-forming capacity in Urea-plasma isolates and the risk for BPD.

METHODS

Forty-three clinical isolates from preterm neonates and five ATCC strains were characterized for their capacity to form biofilms in vitro and antibiotic susceptibility was performed on each isolate pre- and post-biofilm formation.

RESULTS

Forty-one (95%) clinical and 4 of 5 (80%) ATCC isolates formed biofilms. All isolates were more susceptible to azithromycin (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, MIC50 2 μg/mL) than erythromycin (MIC50 4 μg/mL), and biofilm formation did not significantly affect antibiotic susceptibility for the 2 tested antibiotics. The MIC50 and minimum biofilm inhibitory concentrations (MBIC50) for U. urealyticum clinical isolates for azithromycin were higher than for MIC50 and MBIC50 for U. parvum isolates. There were no differences in MIC or MBICs among isolates from BPD infants and non-BPD infants.

CONCLUSIONS

Capacity to form biofilms is common among Ureaplasma spp. isolates, but biofilm-formation did not impact MICs for azithromycin or erythromycin.

Keywords: Ureaplasma parvum, Ureaplasma urealyticum, bacterial biofilms, erythromycin, azithromycin, bronchopulmonary dysplasia

INTRODUCTION

The genital mycoplasmas Ureaplasma parvum (serovars 1, 3, 6, and 14) and U. urealyticum (serovars 2, 4, 5, 7-13) are common commensals in the female genitourinary tract, but colonization with these organisms during pregnancy has been increasingly associated with adverse outcomes such as infertility, stillbirth, intrauterine infection, and preterm birth.1, 2 Vertical transmission may occur in utero or at the time of birth. The organisms can be detected in amniotic fluid,3 placental tissues,4 cord blood,5-7 neonatal respiratory8 and gastric secretions,9 and cerebral spinal fluid.6 Detection of ureaplasmal organisms in preterm infants has been associated with an increased incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD),10, 11 necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC),12 meningitis,13 and abnormal cranial ultrasounds.2 Although the organisms are susceptible to macrolide antibiotics in vitro ,14 trials of erythromycin and azithromyicn in women and infants have failed to demonstrate efficacy for eradication in intrauterine and neonatal lung compartments, prevention of maternal-fetal vertical transmission in humans15, 16 and experimental pregnancy models,17 or prevention of BPD in infected infants.18-24 The mechanisms by which these organisms evade host defenses have not been elucidated.

Biofilms are sessile bacteria attached to a substratum encased in complex structures with an extracellular matrix of polysaccharide, lipid, DNA, and protein.25 Biofilm formation increases microbial resistance to host defenses and antibiotics. Since Mycoplasma species have a limited genome and lack cell walls, it was unknown until recently that these species had the capacity to form biofilms.25-29 García-Castillo et al.30 reported that seven of nine Ureaplasma clinical isolates from the urine of healthy men or those with urethritis or chronic prostatitis formed biofilms in vitro. Whether Ureaplasma isolates from colonized infants can form biofilms is unknown. We hypothesized that Ureaplasma isolates vary in capacity to form biofilms that contribute to their antibiotic resistance and ability to evade host immune responses. This study 1) determined the ability of Ureaplasma spp. isolates from preterm neonates to form biofilms in vitro; 2) compared the susceptibility of the sessile and planktonic organisms to azithromycin and erythromycin; and 3) determined the relationship of biofilm-forming capacity in Urea-plasma spp. isolates and the risk for BPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ureaplasma isolates

Ureaplasma isolates were selected from banked isolates derived from respiratory specimens from preterm neonates admitted to the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) Neonatal Intensive Care Unit that had previously been characterized by real-time PCR for species and in some cases, serotype classification.8 All isolates were within 2 passages from the original patient-derived culture. Five laboratory strains representing U. parvum serotypes 1 (27813), 3 (700970), 6 (27818), and 14 (33697) and U. urealyticum serotype 8 (27618) were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). All isolates stocks were frozen at −80°C prior to experiments.

Preparation of Antibiotic Stock Solutions

Erythromycin and azithromycin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) were used in both conventional antibiotic susceptibility testing and in biofilm susceptibility testing. Stock solutions of 1.6 mg/ml antibiotic in ethanol were prepared and stored at −20 °C until ready for use. A 1:100 dilution (16 ug/mL) of this stock solution in 10B broth medium was prepared for serial dilution in microtiter plates for conventional antibiotic susceptibility testing and biofilm susceptibility testing.

Conventional Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Susceptibility Testing

Conventional MIC susceptibility testing with erythromycin and azithromycin were performed for each isolate in quadruplicate by the broth microdilution method as previously described.30 Cultures of each clinical and laboratory isolate were grown at 37°C for 15-18 hours overnight. One hundred microliter of overnight culture diluted 1:100 in 10B broth (pH 6.0) for final concentration 1 × 104 color changing units/ml was added to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), prepared with serial dilutions of erythromycin and azithromycin. The plates were incubated at 37°C and observed until there was a color change indicating a pH change as a result of Ureaplasma growth in the wells without antibiotics. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration preventing bacterial growth at the time that growth was observed in the positive control wells.

Biofilm Susceptibility Assay

Biofilm susceptibility assays were performed in duplicate as previously described with modifications30. Briefly, 100 μL of a 1:100 dilution of an overnight culture was added to 100 μL of 10B medium (pH 6.0) in each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. For bacterial biofilm formation, pegs of a modified lid (Nunc Immuno™ TSP system, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were immersed into the wells and the plates incubated at 37°C until a color change was observed. The peg lids were washed to remove planktonic organisms by dipping the lids ten times into each of two 96-well plates containing PBS (−Ca2+, −Mg2+). Immediately following the second wash, the lids were placed onto another 96-well plate containing serial dilutions of both erythromycin and azithromycin, each in quadruplicate. To transfer the biofilm forming organisms to the antibiotic-containing medium, the plates were centrifuged at 2,000 x g for ten minutes at 4°C. The peg lids were discarded and replaced with a sterile standard lid. The plates were incubated at 37°C and observed until color change in the positive control wells. The MBIC was defined as the lowest concentration preventing bacterial growth at the time that growth was observed in the positive control wells. Similarly, biofilm formation was determined by growth in the positive control wells of the antibiotic plate.

Clinical outcomes

The clinical characteristics of the cohort from which the banked isolates were obtained have been previously described.8 The respiratory specimens were obtained after parental consent was obtained for protocols approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia severity was defined according to NIH criteria.31 Infants receiving supplemental oxygen at 28 d were assessed at 36 wk postmenstrual age or discharge whichever came first, and were classified as mild BPD if breathing room air; moderate BPD, if receiving supplemental oxygen <30%; or severe BPD, if receiving positive pressure support and/or supplemental oxygen ≥30% at the assessment time point.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Chi square and Wilcoxon signed rank test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The banked clinical isolates selected for biofilm-forming capacity included 26 U. parvum and 17 U. urealyticum isolates (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/B387 which summarizes MICs and MBICs for all isolates tested). Forty-one (95%) clinical and 4 of 5 (80%) ATCC isolates tested formed biofilms under in vitro condtions. The three non-biofilm forming isolates included ATCC 27618, a U. urealyticum serovar 8 strain, and two U. parvum serovar 6 isolates. All isolates were more susceptible to azithromycin (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, MIC50 2 μg/mL) than erythromycin (MIC50 4 μg/mL), and biofilm formation did not significantly affect antibiotic susceptibility for the two tested antibiotics. There was a trend towards lower conventional MICs for erythromycin (p=0.07) and statisically significant lower MICs for azithromycin (p=0.006) for the ATCC strains compared to the MICs for these antibiotics for the clinical isolates (Fig. 1). No tested isolate was resistant to azithromycin. Seven of 48 isolates (14.5%) were resistant to erythromycin (MIC50 ≥ 16 μg/ml) as planktonic cells (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/B387). Of these, 2 were also resistant as biofilm-forming cells. Two additional isolates were sensitive to erythromycin as planktonic cells, but were resistant after biofilm formation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of antibiotic susceptibility of planktonic and sessile cultures of ATCC and clinical isolates. Conventional MIC susceptibility testing with erythromycin and azithromycin were performed for each ATCC (N=5) and clinical (N=43) isolate in quadruplicate by the broth microdilution method and the MBIC determined following biofilm-formation as previously described 30. Data are presented as box plots with the bottom, top, and line through the middle of the box corresponding to the 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and 50th percentile (median), respectively. The whiskers extend from the 10th percentile to the 90th percentile.

Erythro, erythromycin, AZI, azithromycin

*p=0.006 vs AZI MIC50 ATCC strains by Wilcoxon sign rank test

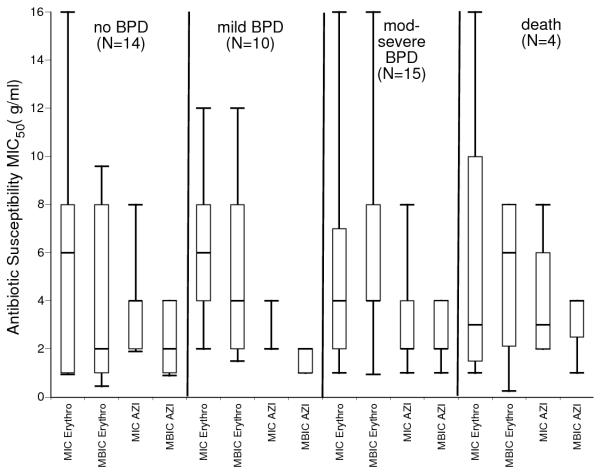

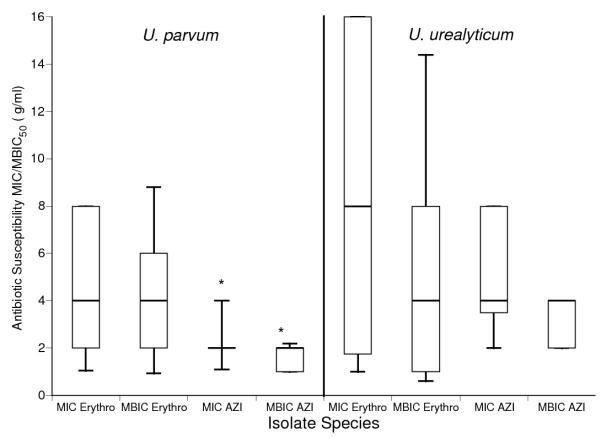

The MIC50 and minimum biofilm inhibitory concentrations (MBIC50) for U. urealyticum clinical isolates for azithromycin were higher than for MIC50 and MBIC50 for U. parvum isolates (Fig. 2). Both U. parvum planktonic and biofilm-forming cells were more susceptible to azithromycin than to erythromycin. The clinical outcomes of the patients from whom the isolates were selected included 14 no BPD, 10 mild BPD, 15 moderate-severe BPD, and 4 deaths.There were no differences in MIC50 or MBIC50 among isolates from BPD/death infants and non-BPD infants (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Comparison of antibiotic susceptibility of planktonic and sessile cultures of U. parvum and U. urealyticum isolates. Conventional MIC susceptibility testing with erythromycin and azithromycin were performed for each U. parvum (N=26) and U. urealyticum (N=17) isolate in quadruplicate by the broth microdilution method and the MBIC determined following biofilm-formation as previously described 30. MIC50 and MBIC50 for erythromycin (Erythro) and azithromycin (AZI). Data are presented as box plots with the bottom, top, and line through the middle of the box corresponding to the 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and 50th percentile (median), respectively. The whiskers extend from the 10th percentile to the 90th percentile.

*p<0.01 compared to U. parvum isolate erythromycin MIC50 and MBIC50 by Wilcoxon sign rank test

†p<0.001 compared to azithromycin MIC50 and MBIC50 U. urealyticum isolates by Wilcoxon sign rank test

Figure 3.

Comparison of clinical isolates MIC50 and MBIC50 by clinical outcomes. There were no significant differences in antibiotic susceptibility among biofilm-forming isolates from infants with and without BPD/death. Data are presented as box plots with the bottom, top, and line through the middle of the box corresponding to the 25th percentile, 75th percentile, and 50th percentile (median), respectively. The whiskers extend from the 10th percentile to the 90th percentile.

DISCUSSION

Considerable effort has focused on determining whether the 10 distinct U. urealyticum and 4 U. parvum serotypes differ in pathogenic potential. Ureaplasma parvum serovars are the most common in clinical specimens, but some earlier antibody-based studies suggested that specific U. urealyticum serovars may have greater pathogenic potential.32-34 Utilizing recently developed serovar specific primers/probes for all 14 serovars,35 we previously demonstrated that serovars 3 and 6, alone and in combination, accounted for 96% of U. parvum isolates from colonized preterm infants in our institution.8 In our population, the U. urealyticum isolates were commonly a mixture of 2 or more serovars. Serovar 11 was the most common U. urealyticum serovar, detected as a single serovar or in combination with other serovars in 56% of U. urealyticum-positive samples. There were no statistical differences among the U. parvum and U. urealyticum species in BPD severity, but the sample size was inadequate to detect a difference at the serovar level. We proposed that there might be virulence genes that are common across multiple serovars that could be targeted to prevent or ameliorate the adverse effects of Ureaplasma infection in the immature lung. Using the genotyped, banked isolates from our previous study,8 the current study was conducted to determine whether biofilm-forming capacity is shared among the Ureaplasma serovars.

The present study confirms that most clinical Ureaplasma isolates derived from preterm infants and U. parvum laboratory strains form biofilms in vitro. We tested isolates representing both species and multiple isolates from the same serovar. Although both non-biofilm forming clinical isolates were serovar 6 strains, other serovar 6 isolates formed biofilms in vitro, suggesting that biofilm-forming capacity is not serovar-specific. Four of five ATCC isolates formed biofilms, indicating that the biofilm-forming capacity is likely stable after multiple passages.

Our study extends the observations of in vitro biofilm-forming capacity of clinical Ureaplasma isolates derived from healthy men and those with urethritis and chronic prostatitis.30 In the previous study, two U. parvum serovar 3, five U. urealyticum serovar 7 and 2 of four U. urealyticum serovar 13 isolates formed biofilms in vitro. Scanning electron microscopy demonstrated that biofilm-forming bacteria adhere to the prostate ductal epithelium in vivo, contributing to organism persistence, chronic inflammation, and antibiotic treatment failures.36 Recently, Romero and co-workers reported a case of M. hominis in vivo biofilm in the intrauterine cavity detected as “amniotic fluid sludge” by transvaginal ultrasound and the complex structure confirmed by scanning electron microscopy.37 Mycoplasma pulmonis intranasally inoculated in mice formed biofilms on the tracheal epithelium in vivo.25 These studies suggest that ureaplasmas colonizing the preterm infant respiratory epithelium may form biofilms that protect the organisms from host defenses and antibiotic treatment. To confirm the biologic relevance of the current in vitro studies, biofilm-formation of clinical Ureaplasma isolates should be tested in in vivo experimental models.

Since erythromycin and azithromycin are the most common antibiotics used clinically in preterm infants to treat Ureaplasma infections, we tested whether biofilm formation by Ureaplasma isolates altered susceptibility to these antibiotics. In agreement with previous studies of in vitro susceptibilities to macrolides, the Ureaplasma isolates in the current study were more susceptible to azithromycin than erythromycin.38-40 In contrast to the decreased susceptibility to erythromycin of sessile cells compared to planktonic cells of Ureaplasma isolates from adult males,30 there was no detectable difference between erythromycin or azithromycin MIC50 and MBIC50 for the Ureaplasma isolates from preterm infants. Since the activity of macrolides in vitro is affected by pH of the medium,41, 42 as well as inoculum size,41 the higher MICs observed in our study may be due, in part, to the acidic pH (6.0) of the 10B broth and variable inoculum size of the transferred sessile cells from the peg lids.

Despite in vitro susceptibility of Ureaplasma to erythromycin and azithromycin, 14, 43 trials of erythromycin or azithromycin therapy in the first few weeks of life in Ureaplasma colonized preterm infants have failed to demonstrate efficacy to prevent BPD,18, 19, 24 or eradicate respiratory tract colonization.21 The failure to prevent BPD in these studies may have been due to the small sample size of each study, or to the initiation of antibiotic therapy too late to prevent the lung inflammation and injury that contribute to the pathogenesis of BPD. Recently, Walls et al.44 demonstrated that azithromycin, but not erythromycin prophylaxis, improved outcomes and reduced inflammation in a murine neonatal Ureaplasma infection model. This suggests that azithromycin may be effective if administered immediately after birth. An initial single dose pharmacokinetic study of 10 mg/kg azithromycin in infants 24-28 weeks gestation suggested that this dose was well-tolerated, but likely insufficient to maintain azithromycin concentrations above the MIC50 for Ureaplasma.45 In the current study, none of the isolates as planktonic or sessile cells were resistant to azithromycin, but 10-15% were resistant to erythromycin. Additional clinical pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies are needed to determine the optimal dosing regimen for azithromycin to eradicate Ureaplasma from the respiratory tract and potentially prevent BPD. Biofilm formation may require higher doses and longer course of therapy for effective eradication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of support: NIH grants R21HD056424 and R01HL087166

Source of Funding: Dr. Viscardi has received grant funding from NIH (R21HD056424 and R01HL087166).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The remaining authors have no conflicts or interest or funding to disclose.

Supplemental Digital Content

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Antibiotic susceptibility to erythromycin and azithromycin of planktonic and sessile cells of Ureaplasma isolates from ATCC reference strains and preterm infants with and without BPD

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Volgmann T, Ohlinger R, Panzig B. Ureaplasma urealyticum-harmless commensal or underestimated enemy of human reproduction? A review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;273:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00404-005-0030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viscardi RM. Ureaplasma species: role in diseases of prematurity. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:393–409. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh KJ, Lee SE, Jung H, et al. Detection of ureaplasmas by the polymerase chain reaction in the amniotic fluid of patients with cervical insufficiency. J Perinat Med. 2010;38:261–268. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2010.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namba F, Hasegawa T, Nakayama M, et al. Placental features of chorioamnionitis colonized with Ureaplasma species in preterm delivery. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:166–172. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c6e58e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Goepfert AR, et al. The Alabama preterm birth study: umbilical cord blood Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis cultures in very preterm newborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:43, e41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viscardi RM, Hashmi N, Gross GW, et al. Incidence of invasive Ureaplasma in VLBW infants: relationship to severe intraventricular hemorrhage. J Perinatol. 2008;28:759–765. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassanein SM, El-Farrash RA, Hafez HM, Hassanin OM, Abd El, Rahman NA. Cord blood interleukin-6 and neonatal morbidities among preterm infants with PCR-positive Ureaplasma urealyticum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 May 3; doi: 10.3109/14767058.2012.678435. ePub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sung TJ, Xiao L, Duffy L, et al. Frequency of Ureaplasma serovars in respiratory secretions of preterm infants at risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:379–383. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318202ac3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oue S, Hiroi M, Ogawa S, et al. Association of gastric fluid microbes at birth with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F17–22. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.138321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang EE, Cassell GH, Sanchez PJ, et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum and chronic lung disease of prematurity: critical appraisal of the literature on causation. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl 1):S112–116. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schelonka RL, Katz B, Waites KB, Benjamin DK., Jr Critical appraisal of the role of Ureaplasma in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia with metaanalytic techniques. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:1033–1039. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000190632.31565.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okogbule-Wonodi AC, Gross GW, Sun CC, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis is associated with ureaplasma colonization in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2011;69:442–447. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182111827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clifford V, Tebruegge M, Everest N, Curtis N. Ureaplasma: pathogen or passenger in neonatal meningitis? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:60–64. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b21016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renaudin H, Bebear C. Comparative in vitro activity of azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin and lomefloxacin against Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:838–841. doi: 10.1007/BF01967388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogasawara KK, Goodwin TM. The efficacy of prophylactic erythromycin in preventing vertical transmission of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14:233–237. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogasawara KK, Goodwin TM. Efficacy of azithromycin in reducing lower genital Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization in women at risk for preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Med. 1999;8:12–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199901/02)8:1<12::AID-MFM3>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dando SJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, et al. Maternal administration of erythromycin fails to eradicate intrauterine ureaplasma infection in an ovine model. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:616–622. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.084954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowman ED, Dharmalingam A, Fan WQ, Brown F, Garland SM. Impact of erythromycin on respiratory colonization of Ureaplasma urealyticum and the development of chronic lung disease in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:615–620. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199807000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonsson B, Rylander M, Faxelius G. Ureaplasma urealyticum, erythromycin and respiratory morbidity in high-risk preterm neonates. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:1079–1084. doi: 10.1080/080352598750031428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyon AJ, McColm J, Middlemist L, et al. Randomised trial of erythromycin on the development of chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;78:F10–F14. doi: 10.1136/fn.78.1.f10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baier RJ, Loggins J, Kruger TE. Failure of erythromycin to eliminate airway colonization with Ureaplasma urealyticum in very low birth weight infants. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mabanta CG, Pryhuber GS, Weinberg GA, Phelps DL. Erythromycin for the prevention of chronic lung disease in intubated preterm infants at risk for, or colonized or infected with Ureaplasma urealyticum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003744. CD003744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mhanna MJ, Delong LJ, Aziz HF. The value of Ureaplasma urealyticum tracheal culture and treatment in premature infants following an acute respiratory deterioration. J Perinatol. 2003;23:541–544. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballard HO, Shook LA, Bernard P, et al. Use of azithromycin for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:111–118. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons WL, Dybvig K. Mycoplasma biofilms ex vivo and in vivo. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;295:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAuliffe L, Ellis RJ, Miles K, Ayling RD, Nicholas RA. Biofilm formation by mycoplasma species and its role in environmental persistence and survival. Microbiology. 2006;152:913–922. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmons WL, Bolland JR, Daubenspeck JM, Dybvig K. A stochastic mechanism for biofilm formation by Mycoplasma pulmonis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1905–1913. doi: 10.1128/JB.01512-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons WL, Dybvig K. Biofilms protect Mycoplasma pulmonis cells from lytic effects of complement and gramicidin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:3696–3699. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00440-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kornspan JD, Tarshis M, Rottem S. Adhesion and biofilm formation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae on an abiotic surface. Arch Microbiol. 2011;193:833–836. doi: 10.1007/s00203-011-0749-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.García-Castillo M, Morosini MI, Gálvez M, et al. Differences in biofilm development and antibiotic susceptibility among clinical Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1027–1030. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naessens A, Foulon W, Breynaert J, Lauwers S. Serotypes of Ureaplasma urealyticum isolated from normal pregnant women and patients with pregnancy complications. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:319–322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.2.319-322.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinn PA, Shewchuk AB, Shuber J, et al. Serologic evidence of Ureaplasma urealyticum infection in women with spontaneous pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;145:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinn PA, Li HCS, Th’ng C, Dunn M, Butany J. Serological response to Ureaplasma urealyticum in the neonate. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl 1):S136–S143. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao L, Glass JI, Paralanov V, et al. Detection and characterization of human ureaplasma species and serovars by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2715–2723. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01877-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nickel JC, Costerton JW, McLean RJ, Olson M. Bacterial biofilms: influence on the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33(Suppl A):31–41. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.suppl_a.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romero R, Schaudinn C, Kusanovic JP, et al. Detection of a microbial biofilm in intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:135, e131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krausse R, Schubert S. In-vitro activities of tetracyclines, macrolides, fluoroquinolones and clindamycin against Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma ssp. isolated in Germany over 20 years. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1649–1655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenny GE, Cartwright FD. Susceptibilities of Mycoplasma hominis, M. pneumoniae, and Ureaplasma urealyticum to GAR-936, dalfopristin, dirithromycin, evernimicin, gatifloxacin, linezolid, moxifloxacin, quinupristin-dalfopristin, and telithromycin compared to their susceptibilities to reference macrolides, tetracyclines, and quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2604–2608. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2604-2608.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waites KB, Crabb DM, Bing X, Duffy LB. In vitro susceptibilities to and bactericidal activities of garenoxacin (BMS-284756) and other antimicrobial agents against human mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:161–165. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.161-165.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waites KB, Figarola TA, Schmid T, et al. Comparison of agar versus broth dilution techniques for determining antibiotic susceptibilities of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;14:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(91)90041-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kenny GE, Cartwright FD. Effect of pH, inoculum size, and incubation time on the susceptibility of Ureaplasma urealyticum to erythromycin in vitro. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl 1):S215–218. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samra Z, Rosenberg S, Dan M. Susceptibility of Ureaplasma urealyticum to tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, roxithromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin. J Chemother. 2011;23:77–79. doi: 10.1179/joc.2011.23.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walls SA, Kong L, Leeming HA, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis improves Ureaplasma-associated lung disease in suckling mice. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:197–202. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181aabd34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hassan HE, Othman AA, Eddington ND, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and biologic effects of azithromycin in extremely preterm infants at risk for Ureaplasma colonization and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51:1264–1275. doi: 10.1177/0091270010382021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.