Abstract

Cigarette smoking is the major environmental risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Genome-wide association studies have provided compelling associations for three loci with COPD. In this study, we aimed to estimate direct, i.e., independent from smoking, and indirect effects of those loci on COPD development using mediation analysis. We included a total of 3,424 COPD cases and 1,872 unaffected controls with data on two smoking-related phenotypes: lifetime average smoking intensity and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke (pack years). Our analysis revealed that effects of two linked variants (rs1051730 and rs8034191) in the AGPHD1/CHRNA3 cluster on COPD development are significantly, yet not entirely, mediated by the smoking-related phenotypes. Approximately 30 % of the total effect of variants in the AGPHD1/CHRNA3 cluster on COPD development was mediated by pack years. Simultaneous analysis of modestly (r2 = 0.21) linked markers in CHRNA3 and IREB2 revealed that an even larger (~42 %) proportion of the total effect of the CHRNA3 locus on COPD was mediated by pack years after adjustment for an IREB2 single nucleotide polymorphism. This study confirms the existence of direct effects of the AGPHD1/CHRNA3, IREB2, FAM13A and HHIP loci on COPD development. While the association of the AGPHD1/CHRNA3 locus with COPD is significantly mediated by smoking-related phenotypes, IREB2 appears to affect COPD independently of smoking.

Introduction

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and integrative genomics approaches have led to the discovery of novel susceptibility loci for many complex phenotypes. Identified variants sometimes overlap between different diseases and traits, which suggest shared genetic mechanisms and common biological pathways involved in these processes. Alternatively, these associations may relate to mediation events, where a marker indirectly affects disease via a direct effect on an intermediate phenotype. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an example of a complex disease that is partially genetically determined. Since a cigarette smoking history is present in most COPD cases, it is plausible that genetic determinants of nicotine addiction significantly contribute to COPD burden. The first COPD susceptibility markers identified by GWAS (Pillai et al. 2009), located in the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain containing 1 (AGPHD1)/cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 3 (CHRNA3) cluster on chromosome 15q25, were also confirmed genetic determinants of smoking intensity (Thorgeirsson et al. 2008, 2010; Saccone et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2010). However, it is unclear whether, and if so to what extent, association of those markers with smoking explains their association with COPD development. Furthermore, it is yet unknown whether association of other postulated COPD susceptibility genes, such as iron-responsive element binding protein 2 (IREB2) (DeMeo et al. 2009; Chappell et al. 2011), family with sequence similarity 13, member A (FAM13A) (Cho et al. 2010), and hedgehog-interacting protein (HHIP) (Wilk et al. 2009; Pillai et al. 2009; Van Durme et al. 2010; Hancock et al. 2010; Repapi et al. 2010; Cho et al. 2010), are independent of smoking history. Of interest, susceptibility variants in IREB2 and AGPHD1/CHRNA3 map to the same region on chromosome 15q25, yet are in only modest linkage disequilibrium (LD). Therefore, we hypothesized that the 15q25 locus contains independent susceptibility loci for COPD development and smoking intensity. Standard linear or logistic regression analysis is unable to dissect indirect effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on a primary (e.g., COPD) phenotype when a causative association between the SNP and an intermediate (e.g., smoking) phenotype exists. To calculate such effects, other methods, such as mediation analysis, are needed. Mediation analysis, popularized by the Baron–Kenny procedure for linear regression models and related “product of coefficient” techniques, was subsumed by Imai et al. (2010a, b) by moving beyond linear models and using the probability scale for estimation of direct and indirect effects. However, the underlying definitions of direct and indirect effects on the causal inference framework date to earlier papers (Robins and Greenland 1992; Pearl 2001). Mediation analysis allowing for case–control study design requires special consideration when obtaining estimates of the association between SNP and mediator and can be performed on the odds ratio scale (Valeri and VanderWeele 2012).

Using mediation analysis, it has been shown that the rs1051730 variant in CHRNA3 significantly affects self-reported, physician-diagnosed COPD directly and indirectly (i.e., via smoking) in a lung cancer case–control study (Wang et al. 2010), although mediation analysis of other COPD susceptibility variants has not been previously reported. The aim of this study was to estimate direct, i.e., the effects that do not belong to pathways containing smoking-related phenotypes studied, and indirect effects of three established COPD susceptibility loci on disease development. We analyzed a cohort of 3,424 COPD cases and 1,872 unaffected controls with data on two smoking-related phenotypes: lifetime average number of cigarettes smoked per day (NCPD) and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke (pack years). We also sought to investigate whether mediation analysis helps in dissecting association signals with COPD and smoking behavior in IREB2 and CHRNA3.

Methods

Subjects and genotyping

We studied current or ex-smoking Caucasian subjects from four independent, case–control cohorts: National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) COPD cases (Fishman et al. 2003) and control subjects from the Normative Aging Study (NAS) (Bell et al. 1972), Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE) (Vestbo et al. 2008), GenKOLS cohort from Bergen, Norway (Zhu et al. 2007), and COPDGene (first 1,000 subjects) (Regan et al. 2010). COPD cases studied had at least moderate COPD [Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage II or higher], while control subjects had normal spirometry according to GOLD criteria (Table 1). Spirometry was performed in accordance with American Thoracic Society criteria in all of the studies included. All smoking-related phenotypes were self-reported using either a Case Report Form (NCPD and pack years in the ECLIPSE cohort only) or modified versions of the American Thoracic Society/Division of Lung Diseases Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (Ferris 1978).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the genotyped subjects (n = 5,296)

| COPD cases (GOLD stage II or higher) n = 3,424 |

Unaffected controls n = 1,872 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Males, n (%) | 2,136 (62.4) | 1,167 (62.3) |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 64.7 (8.0) | 60.2 (10.5) |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1 % predicted,a mean (SD) | 46.5 (17.2) | 98.3 (11.8) |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC, mean (SD)a | 0.45 (0.13) | 0.79 (0.05) |

| NCPD, mean (SD) | 24.1 (12.6) | 21.0 (12.5) |

| Number of pack years, mean (SD)b | 48.1 (27.8) | 30.6 (22.8) |

| GenKOLS subjects, n (%) | 838 (24.5) | 784 (41.9) |

| NETT/NAS subjects, n (%) | 370 (10.8) | 431 (23.0) |

| ECLIPSE subjects, n (%) | 1,735 (50.7) | 176 (9.4) |

| COPDGene subjects, n (%) | 481 (14.0) | 481 (25.7) |

FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; SD, standard deviation; NCPD, lifetime average number of cigarettes smoked per day; NETT, National Emphysema Treatment Trial; NAS, Normative Aging Study; ECLIPSE, Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

Except for eight subjects from the ECLIPSE study and a subset of control subjects from the Normative Aging Study who underwent only pre-bronchodilator FEV1 and FVC measurements

One pack year corresponds to a cumulative exposure due to active smoking of 20 cigarettes per day for 1 year

Five SNPs, that were highly significantly associated with COPD in the recent analysis of the pooled NETT/NAS, ECLIPSE, and GenKOLS cohorts (Cho et al. 2010), and located in CHRNA3 (rs1051730), IREB2 (rs13180), and AGPHD1 (rs8034191; r2 = 0.91 to rs1051730 in CHRNA3) on chromosome 15q25; 5′ upstream of HHIP (rs13118928) on chromosome 4q31; and in FAM13A (rs7671167) on chromosome 4q22, were selected for analysis (Supplementary Table 1). All three of these selected genome-wide significant loci have been replicated in other COPD studies (Lambrechts et al. 2010; Young et al. 2011; Van Durme et al. 2010). The 15q25 region is characterized by a high LD level, and synonymous SNPs in IREB2 (rs13180) and CHRNA3 (rs1051730) tag numerous other SNPs in this region as assessed in the entire cohort studied (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). SNPs were genotyped as a part of the whole-genome genotyping chips, i.e., Illumina Quad 610 (NETT/NAS), Illumina HumanHap 550 (ECLIPSE and GenKOLS), and Illumina Human Omni1-Quad (COPDGene). Since the SNP in the HHIP locus was not present on the Illumina Human Omni1-Quad chip, it was genotyped using a TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the COPDGene cohort as previously reported (Cho et al. 2010).

Quality control procedures

A single, whole-genome datafile of the ECLIPSE, GenKOLS and NETT/NAS cohorts, described previously in detail (Cho et al. 2010), was merged with the COPDGene whole-genome datafile. After quality control, i.e., minor allele frequency ≥0.05, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium p value in control subjects >0.001, and genotyping call rate≥95 %, the final dataset contained approximately 300,000 SNPs. We excluded subjects based on (cryptic) relatedness using PLINK (ver. 1.07) (Purcell et al. 2007) with a pi-hat cutoff of 0.125. Principal component analysis, using Eigensoft software (ver. 3.0) (Price et al. 2006), was performed following our previously reported procedure and revealed 27 significant (p < 0.05 according to Tracy–Widom statistics) principal components for genetic ancestry (PCs). Calculation of PCs resulted in exclusion of subjects based on their ethnic ancestry. Subjects with missing information on either of the two smoking intensity phenotypes studied, as well as those with missing genotyping data for at least one of the polymorphisms of interest, were excluded. In total, 3,424 COPD cases [Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease classification (Rabe et al. 2007) stage II or higher] and 1,872 unaffected controls remained for the analysis (Table 1).

Statistics

We considered both NCPD and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke (i.e., pack years) as phenotypes potentially mediating associations between investigated SNPs and COPD development. We used Box–Cox transformation to transform both phenotypes as dependent variables in linear regression adjusted for 27 PCs and gender in control subjects, using the R package car (Fox and Weisberg 2011). Transformed NCPD and pack-years variables were used in all subsequent analyses. Calculation of indirect-effect odds ratios was performed using a SAS macro recently developed by Valeri and Vanderweele (2012) specifically for case–control studies. We assumed lack of exposure-mediator interaction, since all SNP × smoking-related phenotype interaction terms were not significant in logistic regression analyses on COPD. Proportion of the total effect due to mediation was estimated on a risk difference scale (VanderWeele and Vansteelandt 2010). Since SNPs in CHRNA3 and IREB2 were in significant (r2 = 0.21, D’ = 0.77), yet not complete, LD, we also performed analyses of the CHRNA3 variant conditioned on the IREB2 variant (i.e., the latter used as a covariate), and vice versa. To further explore relationships of both chromosome 15q25 variants with COPD, we performed logistic regression analyses for subgroups of COPD subjects, corresponding to tertiles of pack years smoked, using all available control subjects as a reference group. All statistical analyses were performed in R (R Development Core Team 2010) and SAS (ver. 9.2).

We considered p < 0.05 as nominally significant and p < 5 × 10−8 as genome-wide significant (Dudbridge and Gusnanto 2008).

Results

Associations of genetic variants with smoking intensity

SNPs in CHRNA3 (rs1051730) and AGPHD1 (rs8034191) were significantly associated with higher NCPD (p = 7.6 × 10−5 and p = 3.4 × 10−4, respectively) and pack years (p = 0.005 and p = 0.012, respectively) in control subjects using linear regression adjusted for PCs and gender. Simultaneous analysis of the CHRNA3 and IREB2 SNPs did not change significance of the association of the CHRNA3 SNP with either NCPD or pack years (p = 3.0 × 10−5 and p = 0.004, respectively). No other significant associations between SNPs and smoking-related phenotypes were observed (Supplementary Table 1).

Mediation analysis

All investigated polymorphisms showed at least nominally significant direct effects on COPD development, and variants in FAM13A, AGPHD1 and CHRNA3 achieved genome-wide significance level with NCPD set as mediator (Tables 2, 3). As expected, indirect-effect odds ratios of variants in AGPHD1 and CHRNA3 were nominally significant irrespectively of mediator specified, while other SNPs showed no significant indirect-effect odds ratios (Tables 2, 3). Proportions of the total effect of AGPHD1 and CHRNA3 SNPs on COPD due to mediation were approximately 2–3 times higher for pack years as compared to NCPD set as mediator (Tables 2, 3). Analysis of the CHRNA3 marker conditioned on the IREB2 marker resulted in an increase in the proportion of the effect on COPD due to mediation via either of the smoking intensity phenotype (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Direct and indirect (mediated by NCPD) effects of COPD susceptibility loci

| SNP | Chromosome | Gene | MAF | Minor/major allele |

Direct Effect | Indirect effect | Proportion of total effect due to mediation (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | OR | p | ||||||

| rs7671167 | 4q22 | FAM13A | 0.490 | C/T | 0.781 | 8.2 × 10−9 | 0.996 | 0.610 | – |

| rs13118928 | 4q31 | HHIP (5′ region) | 0.409 | G/A | 0.805 | 3.4 × 10−7 | 1.004 | 0.633 | – |

| rs8034191 | 15q25 | AGPHD1 | 0.383 | C/T | 1.321 | 4.0 × 10−10 | 1.030 | 0.0012 | 10.8 |

| rs1051730 | 15q25 | CHRNA3 | 0.381 | A/G | 1.305 | 2.2 × 10−9 | 1.032 | 0.00044 | 12.1 |

| rs1051730 adjusted for rs13180 | 15q25 | CHRNA3 | 0.381 | A/G | 1.212 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 1.039 | 0.00024 | 18.2 |

| rs13180 | 15q25 | IREB2 | 0.362 | C/T | 0.779 | 1.4 × 10−8 | 0.996 | 0.597 | – |

| rs13180 adjusted for rs1051730 | 15q25 | IREB2 | 0.362 | C/T | 0.850 | 9.8 × 10−4 | 1.013 | 0.160 | – |

NCPD, Lifetime average number of cigarettes smoked per day; OR, odds ratio (additive model) for the major allele set as a reference; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; MAF, minor allele frequency in the whole cohort; FAM13A, family with sequence similarity 13, member A; HHIP, hedgehog-interacting protein; AGPHD1, aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain containing 1; CHRNA3, cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 3; IREB2, iron-responsive element binding protein 2

Bold values indicate indirect effect of p values <0.05

Table 3.

Direct and indirect (mediated by pack years smoked) effects of COPD susceptibility loci

| SNP | Chromosome | Gene | MAF | Minor/major allele |

Direct effect | Indirect effect | Proportion of total effect due to mediation (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | OR | p | ||||||

| rs7671167 | 4q22 | FAM13A | 0.490 | C/T | 0.783 | 9.5 × 10−8 | 1.004 | 0.899 | – |

| rs13118928 | 4q31 | HHIP (5′ region) | 0.409 | G/A | 0.797 | 5.8 × 10−7 | 1.011 | 0.701 | – |

| rs8034191 | 15q25 | AGPHD1 | 0.383 | C/T | 1.273 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 1.077 | 0.013 | 26.4 |

| rs1051730 | 15q25 | CHRNA3 | 0.381 | A/G | 1.256 | 1.4 × 10−6 | 1.085 | 0.0056 | 29.5 |

| rs1051730 adjusted for rs13180 | 15q25 | CHRNA3 | 0.381 | A/G | 1.163 | 4.5 ×10−3 | 1.101 | 0.0038 | 42.0 |

| rs13180 | 15q25 | IREB2 | 0.362 | C/T | 0.788 | 3.8 × 10−7 | 0.988 | 0.668 | – |

| rs13180 adjusted for rs1051730 | 15q25 | IREB2 | 0.362 | C/T | 0.844 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 1.031 | 0.345 | – |

OR, Odds ratio (additive model) for the major allele set as a reference; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; MAF, minor allele frequency in the whole cohort; FAM13A, family with sequence similarity 13, member A; HHIP, hedgehog interacting protein; AGPHD1, aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain containing 1; CHRNA3, cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 3; IREB2, iron-responsive element binding protein 2

Bold values indicate indirect effect of p values <0.05

Associations of CHRNA3 and IREB2 variants with COPD across tertiles of pack years smoked

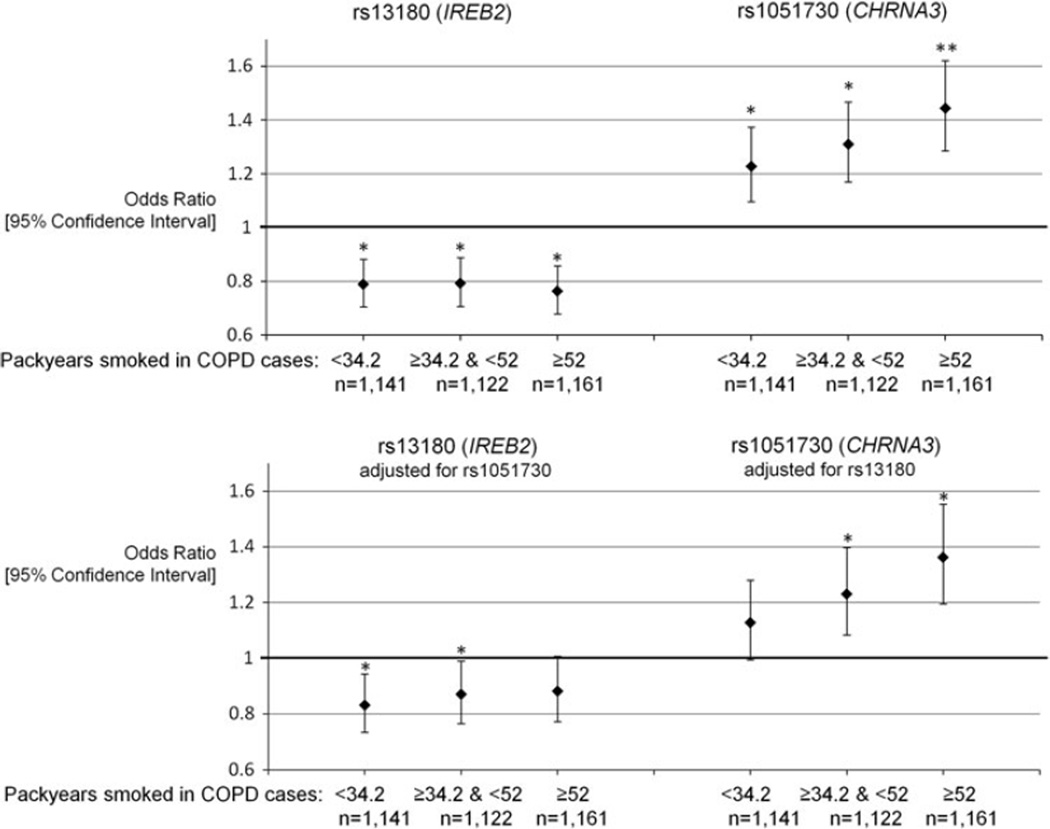

The variant in CHRNA3 showed an increase in odds to develop COPD across tertiles of pack years smoked among COPD cases, suggesting that at least part of the COPD susceptibility association was related to increased smoking intensity related to this SNP (Fig. 1). In contrast, the IREB2 variant showed a similar effect on COPD across tertiles of pack years among COPD cases (Fig. 1). After conditioning on rs1051730, the IREB2 SNP (rs13180) had the most protective effect at the lowest smoking intensity, which suggests a genetic effect on COPD susceptibility that is independent of smoking.

Fig. 1.

Additive effects of variants in IREB2 and CHRNA3 on COPD development according to tertiles of pack years smoked among COPD cases *p < 0.05 **p < 5 × 10−8. Graph demonstrates the odds for COPD for specific tertiles of pack years smoked among COPD cases. All the unaffected control subjects (n = 1,872) were set as a reference group. Analyses were adjusted for 27 PCs and gender. PCs, Principal components for genetic ancestry; CHRNA3, cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 3; IREB2, iron-responsive element binding protein 2; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Discussion

By applying mediation analysis, this study confirmed that all of the analyzed susceptibility loci for COPD possess direct effects, independent of smoking, on disease development. Simultaneous analyses of 15q25 variants suggested that the IREB2 rs13180 variant associates with COPD via pathways other than smoking intensity, while a substantial proportion of the effect of the CHRNA3 rs1051730 variant on COPD is mediated by the cumulative amount of tobacco smoked.

We demonstrated that, in contrast to the IREB2 SNP, the odds for COPD development for the CHRNA3 SNP are higher while analyzing COPD subjects with a large smoking history as compared to those with a lower smoking history. Since the subset of COPD cases with the highest smoking history is likely enriched with risk variants for phenotypes related to nicotine addiction, this strongly suggests that CHRNA3, rather than IREB2, affects COPD via smoking-related pathways.

Identification of genetic markers associated with complex traits in the presence of strong environmental or behavioral risk factors may not be straightforward when a high genetic predisposition to exposure to such factors occurs. Variants in the 15q25 locus, containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes CHRNA3, CHRNA5 and CHRNB4, were identified in GWAS on lung cancer (Thorgeirsson et al. 2008; Amos et al. 2008; Hung et al. 2008). Subsequent multi-cohort studies showed that these same markers determine level of smoking intensity and were associated with the development of COPD (Pillai et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2010; Thorgeirsson et al. 2010). Thus, it is tempting to conclude that smoking mediates the association of the 15q25 locus with both COPD and lung cancer. The extent to which such mediation occurs has been addressed by Wang et al. (2010), who found both a significant direct and indirect (i.e., via pack years) effect of rs1051730 on lung cancer and COPD using a mediation analysis approach. Our study showed a slightly higher proportion (30 %) of the total effect of this variant on COPD being mediated by pack years compared to the study of Wang and colleagues (23.6 %), which may be a consequence of larger sample size and different disease definition in the present study. Importantly, our analysis clearly showed that pack years rather than NCPD possess more pronounced potential to mediate genetic associations with COPD. This may seem intuitive given the cumulative nature of pack years, although it is important to acknowledge that pack years are determined by other, possibly genetically determined, traits, i.e., age at smoking initiation and cessation (or current age).

DeMeo et al. (2009) suggested that marker rs1051730 in CHRNA3 and linked SNPs may not be the only independent genetic associations with COPD in the 15q25 region. Using an integrative genomics approach, they identified IREB2 as a novel susceptibility gene for COPD in this locus, which was subsequently replicated by an independent multinational study (Chappell et al. 2011). Our analyses of the IREB2 variant suggested that the association with COPD is not mediated by pack years, and this lack of mediation by pack years persisted after conditioning for the CHRNA3 variant as well. Furthermore, the proportion of the total effect on COPD due to mediation for the rs1051730 variant in CHRNA3 increased from 30 to 42 % while conditioning for the IREB2 variant, which strengthens the hypothesis that CHRNA3 affects COPD primarily via smoking intensity-related pathways. On the other hand, our conclusion that the effect of the CHRNA3 variant is not entirely mediated by smoking-related phenotypes supports recent GWAS on COPD, which found similar, statistically significant, odds to develop COPD both among never and ever smokers for the rs1051730 CHRNA3 variant (Wilk et al. 2012).

Our study additionally investigated other variants previously shown to be valid susceptibility loci for the development of COPD. Not surprisingly, results for the rs8034191 SNP in AGPHD1 were very similar to those for rs1051730 due to high level of LD between these two SNPs, while variants in FAM13A and HHIP showed no significant indirect effects. Given the fact that previous independent GWAS associated the FAM13A locus with the level of lung function (Hancock et al. 2010; Repapi et al. 2010; Van Durme et al. 2010), we believe that the investigated FAM13A and HHIP SNPs, or linked variants, influence COPD susceptibility through pathways other than the phenotypes studied, which were related to nicotine addiction.

There are some limitations to our study that need to be addressed. PCs and gender were considered as common factors influencing NCPD, pack years and COPD development; however, there may be other unmeasured factors (such as exposure to stress, educational status or socioeconomical status) that affect these phenotypes. However, if these factors are affected by the genetic variants studied, other methods, such as causal modeling (Vansteelandt et al. 2009) or G-estimation (Vansteelandt 2009) approaches, are necessary to estimate direct effects. Likewise, if the interaction between exposure and the mediator occurs, e.g., in the lung cancer study where 15q25 variants significantly interacted with smoking (VanderWeele et al. 2012), this should be taken into account in the mediation analysis (Valeri and VanderWeele 2012). The genetics of complex diseases, such as COPD, should be preferably investigated using large cohorts. Although we pooled four available genome-wide association datasets, which resulted in a sample size of 5,296 subjects, we may have not achieved sufficient statistical power to detect genome-wide significant associations concerning direct or indirect effects. The intermediate smoking intensity phenotypes studied were characterized by a limited assessment. Self-reporting of smoking behaviors in our study could have been affected by a low accuracy, and especially while reporting lifetime average smoking intensity or age at smoking initiation or duration of smoking variables, which were used to calculate pack years. This phenomenon has been observed for the rs1051730 variant, which showed stronger association with objective, as compared to self-reported, measures of smoking intensity, i.e., plasma/serum cotinine level (Munafo et al. 2012).

In addition to the three genetic loci which we analyzed, there are likely multiple additional COPD susceptibility loci. Previous reports have suggested genetic determinants of COPD based on candidate gene studies [e.g., SFTPD (Foreman et al. 2011)], fine mapping studies [e.g., XRCC5 (Hersh et al. 2010)], GWAS of other phenotypes [e.g., BICD1 for emphysema (Kong et al. 2011)], and GWAS loci of COPD which have not yet been replicated [e.g., CYP2A6 region on chromosome 19 (Cho et al. 2012)]. If the evidence supporting these or other novel COPD susceptibility loci improves, mediation analysis to determine direct versus indirect effects of smoking would be beneficial.

Using a large population of well-characterized COPD patients and unaffected controls, we demonstrated that variants in AGPHD1, CHRNA3, IREB2, HHIP and FAM13A have significant direct effects, i.e., independent of smoking, on the development of COPD. Simultaneous analysis of the 15q25 locus shows no significant effect of IREB2 on COPD that is mediated by smoking, while a variant in CHRNA3 affects COPD predominantly via association with cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Kosuke Imai from the Department of Politics at the Princeton University and Dr Stijn Vansteelandt from the Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Sciences at the Ghent University for their comprehensive help with mediation analysis. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 HL075478, R01 HL084323, P01 HL083069, P01 HL105339, and U01 HL089856 (E.K.S.); K12HL089990 and K08 HL097029 (M.H.C); and U01 HL089897 (J.D.C.). M.S. is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Niels Stensen Foundation. The NETT was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NAS is supported by the Cooperative Studies Program/ERIC of the US Department of Veterans Affairs and is a component of the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC). The Norway GenKOLS study (Genetics of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, GSK code RES11080) and the ECLIPSE study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00292552; GSK code SCO104960) are funded by GlaxoSmithKline. The COPDGene project is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board comprised of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sunovion.

We acknowledge the co-investigators in the NETT Genetics Ancillary Study including Joshua Benditt, Gerard Criner, Malcolm DeCamp, Philip Diaz, Mark Ginsburg, Larry Kaiser, Marcia Katz, Mark Krasna, Neil MacIntyre, Barry Make, Rob McKenna, Fernando Martinez, Zab Mosenifar, John Reilly, Andrew Ries, Paul Scanlon, Frank Sciurba, and James Utz.

Appendix

ECLIPSE Steering Committee

Harvey Coxson (Canada), Lisa Edwards (GlaxoSmithKline, USA), David Lomas (UK), William MacNee (UK), Edwin Silverman (USA), Ruth Tal-Singer (Co-chair, GlaxoSmithKline, USA), Jørgen Vestbo (Co-chair, Denmark), Julie Yates (GlaxoSmithKline, USA).

ECLIPSE Scientific Committee

Alvar Agusti (Spain), Per Bakke (Norway), Peter Calverley (UK), Bartolome Celli (USA), Courtney Crim (GlaxoSmithKline, USA), Bruce Miller (GlaxoSmithKline, UK), William MacNee (Chair, UK), Stephen Rennard (USA), Ruth Tal-Singer (GlaxoSmithKline, USA), Emiel Wouters (The Netherlands).

ECLIPSE Investigators

Bulgaria: Yavor Ivanov, Pleven; Kosta Kostov, Sofia. Canada: Jean Bourbeau, Montreal, Que; Mark Fitzgerald, Vancouver, BC; Paul Hernandez, Halifax, NS; Kieran Killian, Hamilton, On; Robert Levy, Vancouver, BC; Francois Maltais, Montreal, Que; Denis O’Donnell, Kingston, On. Czech Republic: Jan Krepelka, Praha. Denmark: Jørgen Vestbo, Hvidovre. Netherlands: Emiel Wouters, Horn-Maastricht. New Zealand: Dean Quinn, Wellington. Norway: Per Bakke, Bergen. Slovenia: Mitja Kosnik, Golnik. Spain: Alvar Agusti, Jaume Sauleda, Palma de Mallorca. Ukraine: Yuri Feschenko, Kiev; Vladamir Gavrisyuk, Kiev; Lyudmila Yashina, Kiev; Nadezhda Monogarova, Donetsk. United Kingdom: Peter Calverley, Liverpool; David Lomas, Cambridge; William MacNee, Edinburgh; David Singh, Manchester; Jadwiga Wedzicha, London. United States of America: Antonio Anzueto, San Antonio, TX; Sidney Braman, Providence, RI; Richard Casaburi, Torrance CA; Bart Celli, Boston, MA; Glenn Giessel, Richmond, VA; Mark Gotfried, Phoenix, AZ; Gary Greenwald, Rancho Mirage, CA; Nicola Hanania, Houston, TX; Don Mahler, Lebanon, NH; Barry Make, Denver, CO; Stephen Rennard, Omaha, NE; Carolyn Rochester, New Haven, CT; Paul Scanlon, Rochester, MN; Dan Schuller, Omaha, NE; Frank Sciurba, Pittsburgh, PA; Amir Sharafkhaneh, Houston, TX; Thomas Siler, St. Charles, MO, Edwin Silverman, Boston, MA; Adam Wanner, Miami, FL; Robert Wise, Baltimore, MD; Richard ZuWallack, Hartford, CT.

COPDGene Investigators

The members of the COPDGene study group as of June 2010

Ann Arbor VA: Jeffrey Curtis, MD (PI), Ella Kazerooni, MD (RAD)

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, MD, MS (PI), Philip Alapat, MD, Venkata Bandi, MD, Kalpalatha Guntupalli, MD, Elizabeth Guy, MD, Antara Mallampalli, MD, Charles Trinh, MD (RAD), Mustafa Atik, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH (Co-PI), Craig Hersh, MD, MPH (Co-PI), George Washko, MD, Francine Jacobson, MD, MPH (RAD)

Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH (PI), Byron Thomashow, MD, John Austin, MD (RAD)

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre, Jr., MD (PI), Lacey Washington, MD (RAD), H Page McAdams, MD (RAD)

Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, MD (PI), Timothy Bresnahan, MD (RAD)

Health Partners Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH (PI), Joseph Tashjian, MD (RAD)

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, MD (PI), Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Robert Brown, MD (RAD), Gregory Diette, MD

Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA: Richard Casaburi, MD (PI), Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD, Hans Fischer, MD, PhD (RAD), Matt Budoff, MD

Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD (PI), Charles Trinh, MD (RAD), Hirani Kamal, MD, Roham Darvishi, MD

Minneapolis VA: Dennis Niewoehner, MD (PI), Tadashi Allen, MD (RAD), Quentin Anderson, MD (RAD), Kathryn Rice, MD

Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Marilyn Foreman, MD, MS (PI), Gloria Westney, MD, MS, Eugene Berkowitz, MD, PhD (RAD)

National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, MD, PhD (PI), Adam Friedlander, MD, David Lynch, MB (RAD), Joyce Schroeder, MD (RAD), John Newell, Jr., MD (RAD)

Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, MD (PI), Victor Kim, MD, Nathaniel Marchetti, DO, Aditi Satti, MD, A. James Mamary, MD, Robert Steiner, MD (RAD), Chandra Dass, MD (RAD)

University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: William Bailey, MD (PI), Mark Dransfield, MD (Co-PI), Hrudaya Nath, MD (RAD)

University of California, San Diego, CA: Joe Ramsdell, MD (PI), Paul Friedman, MD (RAD)

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Geoffrey McLennan, MD, PhD (PI), Edwin JR van Beek, MD, PhD (RAD), Brad Thompson, MD (RAD), Dwight Look, MD

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Fernando Martinez, MD (PI), MeiLan Han, MD, Ella Kazerooni, MD (RAD)

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Christine Wendt, MD (PI), Tadashi Allen, MD (RAD)

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, MD (PI), Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH, Carl Fuhrman, MD (RAD), Jessica Bon, MD

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Antonio Anzueto, MD (PI), Sandra Adams, MD, Carlos Orozco, MD, Mario Ruiz, MD (RAD)

Administrative Core: James Crapo, MD (PI), Edwin Silverman, MD, PhD (PI), Barry Make, MD, Elizabeth Regan, MD, Sarah Moyle, MS, Douglas Stinson

Genetic Analysis Core: Terri Beaty, PhD, Barbara Klanderman, PhD, Nan Laird, PhD, Christoph Lange, PhD, Michael Cho, MD, Stephanie Santorico, PhD, John Hokanson, MPH, PhD, Dawn DeMeo, MD, MPH, Nadia Hansel, MD, MPH, Craig Hersh, MD, MPH, Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS, Tanda Murray.

Imaging Core: David Lynch, MB, Joyce Schroeder, MD, John Newell, Jr., MD, John Reilly, MD, Harvey Coxson, PhD, Philip Judy, PhD, Eric Hoffman, PhD, George Washko, MD, Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD, James Ross, MSc, Rebecca Leek, Jordan Zach, Alex Kluiber, Jered Sieren, Heather Baumhauer, Verity McArthur, Dzimitry Kazlouski, Andrew Allen, Tanya Mann, Anastasia Rodionova

PFT QA Core, LDS Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, PhD

Biological Repository, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Homayoon Farzadegan, PhD, Stacey Meyerer, Shivam Chandan, Samantha Bragan

Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: James Murphy, PhD, Douglas Everett, PhD, Carla Wilson, MS, Ruthie Knowles, Amber Powell, Joe Piccoli, Maura Robinson, Margaret Forbes, Martina Wamboldt

Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, CO: John Hokanson, MPH, PhD, Marci Sontag, PhD, Jennifer Black-Shinn, MPH, Gregory Kinney, MPH.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00439-012-1262-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest No competing interests: MS, DT, AG, AAL, PJL, CL, DS; GlaxoSmithKline employee: WA, XK; NHLBI grant: JEH, THB; NIH grant: MHC, EKS, JDC; GlaxoSmithKline grant: EKS, DAL, PB; COPD Foundation grant: EKS, JDC; GlaxoSmithKline consulting fee or honorarium and support for travel to meetings for the study or other purposes: EKS, DAL; COPD Foundation support for travel to meetings for the study or other purposes: EKS, JDC; AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline—payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus and consultancy (outside the submitted work): EKS, PB; Pfizer—payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus and consultancy (outside the submitted work): PB; GlaxoSmithKline—board membership, consultancy, payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus and consultancy (outside the submitted work): DAL; Boehringer Ingelheim consultancy (outside the submitted work): DAL; GlaxoSmithKline fees for participation in review activities such as data monitoring boards, statistical analysis, end point committees, and the like: DAL; Consulting fee or honorarium from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Otsuka: SIR; Grant from AstraZeneca, Biomarck, Centocor, Mpex, Nabi, Novartis, Otsuka: SIR; Almirall, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer board membership (outside the submitted work): SIR; Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, California Allergy Society, Creative Educational Concept, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Information TV, Network for Continuing Education, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer—travel/accommodations expenses covered or reimbursed (outside the submitted work): SIR; Able Associates, Adelphi Research, APT Pharma/Britnall, Aradigm, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CommonHealth, Consult Complete, COPDForum, Data Monitor, Decision Resource, Defined Health, Dey, Dunn Group, Easton Associates, Equinox, Gerson, GlaxoSmithKline, Infomed, KOL Connection, M. Pankove, MedaCorp, MDRx Financial, Mpex, Oriel Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pennside, PharmaVentures, Pharmaxis, Price Waterhouse, Propagate, Pulmatrix, Reckner Associates, Recruiting Resources, Roche, Schlesinger Medical, Scimed, Sudler and Hennessey, TargeGen, Theravance, UBC, Uptake Medical, VantagePoint Mangement—consultancy (outside the submitted work): SIR.

Contributor Information

Mateusz Siedlinski, Email: remts@channing.harvard.edu, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 181 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Dustin Tingley, Department of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Peter J. Lipman, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, USA

Michael H. Cho, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 181 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Augusto A. Litonjua, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 181 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

David Sparrow, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System and Boston University Schools of Public Health and Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Per Bakke, Department of Thoracic Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital and Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Amund Gulsvik, Department of Thoracic Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital and Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

David A. Lomas, Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Wayne Anderson, GlaxoSmithKline Research and Development, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

Xiangyang Kong, GlaxoSmithKline Research and Development, King of Prussia, PA, USA.

Stephen I. Rennard, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

Terri H. Beaty, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

John E. Hokanson, Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO, USA

James D. Crapo, Department of Medicine, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO, USA

Christoph Lange, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, USA.

Edwin K. Silverman, Email: ed.silverman@channing.harvard.edu, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 181 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, Dong Q, Zhang Q, Gu X, Vijayakrishnan J, Sullivan K, Matakidou A, Wang Y, Mills G, Doheny K, Tsai YY, Chen WV, Shete S, Spitz MR, Houlston RS. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):616–622. doi: 10.1038/ng.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell B, Rose CL, Damon H. The Normative Aging Study: an interdisciplinary and longitudinal study of health and aging. Aging Hum Dev. 1972;3(3):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell SL, Daly L, Lotya J, Alsaegh A, Guetta-Baranes T, Roca J, Rabinovich R, Morgan K, Millar AB, Donnelly SC, Keatings V, MacNee W, Stolk J, Hiemstra PS, Miniati M, Monti S, O’Connor CM, Kalsheker N. The role of IREB2 and transforming growth factor beta-1 genetic variants in COPD: a replication case–control study. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Boutaoui N, Klanderman BJ, Sylvia JS, Ziniti JP, Hersh CP, DeMeo DL, Hunninghake GM, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, Lange C, Won S, Murphy JR, Beaty TH, Regan EA, Make BJ, Hokanson JE, Crapo JD, Kong X, Anderson WH, Tal-Singer R, Lomas DA, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Pillai SG, Silverman EK. Variants in FAM13A are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42(3):200–202. doi: 10.1038/ng.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Castaldi PJ, Wan ES, Siedlinski M, Hersh CP, Demeo DL, Himes BE, Sylvia JS, Klanderman BJ, Ziniti JP, Lange C, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, Regan EA, Make BJ, Hokanson JE, Murray T, Hetmanski JB, Pillai SG, Kong X, Anderson WH, Tal-Singer R, Lomas DA, Coxson HO, Edwards LD, MacNee W, Vestbo J, Yates JC, Agusti A, Calverley PM, Celli B, Crim C, Rennard S, Wouters E, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Crapo JD, Beaty TH, Silverman EK. A genome-wide association study of COPD identifies a susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q13. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(4):947–957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMeo DL, Mariani T, Bhattacharya S, Srisuma S, Lange C, Litonjua A, Bueno R, Pillai SG, Lomas DA, Sparrow D, Shapiro SD, Criner GJ, Kim HP, Chen Z, Choi AM, Reilly J, Silverman EK. Integration of genomic and genetic approaches implicates IREB2 as a COPD susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(4):493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F, Gusnanto A. Estimation of significance thresholds for genomewide association scans. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32(3):227–234. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(6 Pt 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, Weinmann G, Wood DE. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(21):2059–2073. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman MG, Kong X, DeMeo DL, Pillai SG, Hersh CP, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lomas DA, Litonjua AA, Shapiro SD, Tal-Singer R, Silverman EK. Polymorphisms in surfactant protein-D are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(3):316–322. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0360OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Weisberg S. An R companion to applied regression. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, Franceschini N, van Durme YM, Chen TH, Barr RG, Schabath MB, Couper DJ, Brusselle GG, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM, Rotter JI, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Punjabi NM, Rivadeneira F, Morrison AC, Enright PL, North KE, Heckbert SR, Lumley T, Stricker BH, O’Connor GT, London SJ. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):45–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh CP, Pillai SG, Zhu G, Lomas DA, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, DeMeo DL, Klanderman BJ, Lazarus R, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, Reilly JJ, Agusti A, Calverley PM, Donner CF, Levy RD, Make BJ, Pare PD, Rennard SI, Vestbo J, Wouters EF, Scholand MB, Coon H, Hoidal J, Silverman EK. Multistudy fine mapping of chromosome 2q identifies XRCC5 as a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility gene. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):605–613. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1586OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, Zaridze D, Mukeria A, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Lissowska J, Rudnai P, Fabianova E, Mates D, Bencko V, Foretova L, Janout V, Chen C, Goodman G, Field JK, Liloglou T, Xinarianos G, Cassidy A, McLaughlin J, Liu G, Narod S, Krokan HE, Skorpen F, Elvestad MB, Hveem K, Vatten L, Linseisen J, Clavel-Chapelon F, Vineis P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Lund E, Martinez C, Bingham S, Rasmuson T, Hainaut P, Riboli E, Ahrens W, Benhamou S, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Holcatova I, Merletti F, Kjaerheim K, Agudo A, Macfarlane G, Talamini R, Simonato L, Lowry R, Conway DI, Znaor A, Healy C, Zelenika D, Boland A, Delepine M, Foglio M, Lechner D, Matsuda F, Blanche H, Gut I, Heath S, Lathrop M, Brennan P. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature. 2008;452(7187):633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature06885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods. 2010a;15(4):309–334. doi: 10.1037/a0020761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Keele L, Yamamoto T. Identification, inference and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat Sci. 2010b;25:51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Cho MH, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Muller N, Washko G, Hoffman EA, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Pillai SG. Genome-wide association study identifies BICD1 as a susceptibility gene for emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(1):43–49. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0541OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts D, Buysschaert I, Zanen P, Coolen J, Lays N, Cuppens H, Groen HJ, Dewever W, van Klaveren RJ, Verschakelen J, Wijmenga C, Postma DS, Decramer M, Janssens W. The 15q24/25 susceptibility variant for lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(5):486–493. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1364OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, Tozzi F, Waterworth DM, Pillai SG, Muglia P, Middleton L, Berrettini W, Knouff CW, Yuan X, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Preisig M, Wareham NJ, Zhao JH, Loos RJ, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Grundy S, Barter P, Mahley R, Kesaniemi A, McPherson R, Vincent JB, Strauss J, Kennedy JL, Farmer A, McGuffin P, Day R, Matthews K, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lucae S, Ising M, Brueckl T, Horstmann S, Wichmann HE, Rawal R, Dahmen N, Lamina C, Polasek O, Zgaga L, Huffman J, Campbell S, Kooner J, Chambers JC, Burnett MS, Devaney JM, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler L, Lindsay JM, Waksman R, Epstein S, Wilson JF, Wild SH, Campbell H, Vitart V, Reilly MP, Li M, Qu L, Wilensky R, Matthai W, Hakonarson HH, Rader DJ, Franke A, Wittig M, Schafer A, Uda M, Terracciano A, Xiao X, Busonero F, Scheet P, Schlessinger D, St Clair D, Rujescu D, Abecasis GR, Grabe HJ, Teumer A, Volzke H, Petersmann A, John U, Rudan I, Hayward C, Wright AF, Kolcic I, Wright BJ, Thompson JR, Balmforth AJ, Hall AS, Samani NJ, Anderson CA, Ahmad T, Mathew CG, Parkes M, Satsangi J, Caulfield M, Munroe PB, Farrall M, Dominiczak A, Worthington J, Thomson W, Eyre S, Barton A, Mooser V, Francks C, Marchini J. Meta-analysis and imputation refines the association of 15q25 with smoking quantity. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):436–440. doi: 10.1038/ng.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Timofeeva MN, Morris RW, Prieto-Merino D, Sattar N, Brennan P, Johnstone EC, Relton C, Johnson PC, Walther D, Whincup PH, Casas JP, Uhl GR, Vineis P, Padmanabhan S, Jefferis BJ, Amuzu A, Riboli E, Upton MN, Aveyard P, Ebrahim S, Hingorani AD, Watt G, Palmer TM, Timpson NJ, Davey Smith G. Association between genetic variants on chromosome 15q25 locus and objective measures of tobacco exposure. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(10):740–748. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J. Direct and indirect effects. In: Breese JS, Koller D, editors. Proceedings of the 17th conference on uncertainty in artificial intelligence; Morgan Kaufman, San Francisco. 2001. pp. 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai SG, Ge D, Zhu G, Kong X, Shianna KV, Need AC, Feng S, Hersh CP, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Ruppert A, Lodrup Carlsen KC, Roses A, Anderson W, Rennard SI, Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Goldstein DB. A genome-wide association study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): identification of two major susceptibility loci. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000421. e1000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. http://www.Rproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, Zielinski J. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Silverman EK, Crapo JD. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repapi E, Sayers I, Wain LV, Burton PR, Johnson T, Obeidat M, Zhao JH, Ramasamy A, Zhai G, Vitart V, Huffman JE, Igl W, Albrecht E, Deloukas P, Henderson J, Granell R, McArdle WL, Rudnicka AR, Barroso I, Loos RJ, Wareham NJ, Mustelin L, Rantanen T, Surakka I, Imboden M, Wichmann HE, Grkovic I, Jankovic S, Zgaga L, Hartikainen AL, Peltonen L, Gyllensten U, Johansson A, Zaboli G, Campbell H, Wild SH, Wilson JF, Glaser S, Homuth G, Volzke H, Mangino M, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Polasek O, Rudan I, Wright AF, Heliovaara M, Ripatti S, Pouta A, Naluai AT, Olin AC, Toren K, Cooper MN, James AL, Palmer LJ, Hingorani AD, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Ebrahim S, McKeever TM, Pavord ID, MacLeod AK, Morris AD, Porteous DJ, Cooper C, Dennison E, Shaheen S, Karrasch S, Schnabel E, Schulz H, Grallert H, Bouatia-Naji N, Delplanque J, Froguel P, Blakey JD, Britton JR, Morris RW, Holloway JW, Lawlor DA, Hui J, Nyberg F, Jarvelin MR, Jackson C, Kahonen M, Kaprio J, Probst-Hensch NM, Koch B, Hayward C, Evans DM, Elliott P, Strachan DP, Hall IP, Tobin MD. Genome-wide association study identifies five loci associated with lung function. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):36–44. doi: 10.1038/ng.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Greenland S. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 1992;3(2):143–155. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone NL, Culverhouse RC, Schwantes-An TH, Cannon DS, Chen X, Cichon S, Giegling I, Han S, Han Y, Keskitalo-Vuokko K, Kong X, Landi MT, Ma JZ, Short SE, Stephens SH, Stevens VL, Sun L, Wang Y, Wenzlaff AS, Aggen SH, Breslau N, Broderick P, Chatterjee N, Chen J, Heath AC, Heliovaara M, Hoft NR, Hunter DJ, Jensen MK, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Niu T, Payne TJ, Peltonen L, Pergadia ML, Rice JP, Sherva R, Spitz MR, Sun J, Wang JC, Weiss RB, Wheeler W, Witt SH, Yang BZ, Caporaso NE, Ehringer MA, Eisen T, Gapstur SM, Gelernter J, Houlston R, Kaprio J, Kendler KS, Kraft P, Leppert MF, Li MD, Madden PA, Nothen MM, Pillai S, Rietschel M, Rujescu D, Schwartz A, Amos CI, Bierut LJ. Multiple independent loci at chromosome 15q25.1 affect smoking quantity: a meta-analysis and comparison with lung cancer and COPD. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001053. e1001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, Manolescu A, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Ingason A, Stacey SN, Bergthorsson JT, Thorlacius S, Gudmundsson J, Jonsson T, Jakobsdottir M, Saemundsdottir J, Olafsdottir O, Gudmundsson LJ, Bjornsdottir G, Kristjansson K, Skuladottir H, Isaksson HJ, Gudbjartsson T, Jones GT, Mueller T, Gottsater A, Flex A, Aben KK, de Vegt F, Mulders PF, Isla D, Vidal MJ, Asin L, Saez B, Murillo L, Blondal T, Kolbeinsson H, Stefansson JG, Hansdottir I, Runarsdottir V, Pola R, Lindblad B, van Rij AM, Dieplinger B, Haltmayer M, Mayordomo JI, Kiemeney LA, Matthiasson SE, Oskarsson H, Tyrfingsson T, Gudbjartsson DF, Gulcher JR, Jonsson S, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature. 2008;452(7187):638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature06846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson TE, Gudbjartsson DF, Surakka I, Vink JM, Amin N, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Esko T, Walter S, Gieger C, Rawal R, Mangino M, Prokopenko I, Magi R, Keskitalo K, Gudjonsdottir IH, Gretarsdottir S, Stefansson H, Thompson JR, Aulchenko YS, Nelis M, Aben KK, den Heijer M, Dirksen A, Ashraf H, Soranzo N, Valdes AM, Steves C, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Tonjes A, Kovacs P, Hottenga JJ, Willemsen G, Vogelzangs N, Doring A, Dahmen N, Nitz B, Pergadia ML, Saez B, De Diego V, Lezcano V, Garcia-Prats MD, Ripatti S, Perola M, Kettunen J, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Laitinen J, Isohanni M, Huei-Yi S, Allen M, Krestyaninova M, Hall AS, Jones GT, van Rij AM, Mueller T, Dieplinger B, Haltmayer M, Jonsson S, Matthiasson SE, Oskarsson H, Tyrfingsson T, Kiemeney LA, Mayordomo JI, Lindholt JS, Pedersen JH, Franklin WA, Wolf H, Montgomery GW, Heath AC, Martin NG, Madden PA, Giegling I, Rujescu D, Jarvelin MR, Salomaa V, Stumvoll M, Spector TD, Wichmann HE, Metspalu A, Samani NJ, Penninx BW, Oostra BA, Boomsma DI, Tiemeier H, van Duijn CM, Kaprio J, Gulcher JR, McCarthy MI, Peltonen L, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Sequence variants at CHRNB3-CHRNA6 and CYP2A6 affect smoking behavior. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):448–453. doi: 10.1038/ng.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeri L, VanderWeele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0031034. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Durme YM, Eijgelsheim M, Joos GF, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Brusselle GG, Stricker BH. Hedgehog-interacting protein is a COPD susceptibility gene: the Rotterdam Study. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(1):89–95. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00129509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(12):1339–1348. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, Asomaning K, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Han Y, Spitz, Shete S, Wu X, Gaborieau V, Wang Y, McLaughlin J, Hung RJ, Brennan P, Amos CI, Christiani DC, Lin X. Genetic variants on 15q25.1, smoking, and lung cancer: an assessment of mediation and interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):1013–1020. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteelandt S. Estimating direct effects in cohort and case-control studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):851–860. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181b6f4c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteelandt S, Goetgeluk S, Lutz S, Waldman I, Lyon H, Schadt EE, Weiss ST, Lange C. On the adjustment for covariates in genetic association analysis: a novel, simple principle to infer direct causal effects. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33(5):394–405. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Crim C, Dawber F, Edwards L, Hagan G, Knobil K, Lomas DA, MacNee W, Silverman EK, Tal-Singer R. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE) Eur Respir J. 2008;31(4):869–873. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00111707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Spitz MR, Amos CI, Wilkinson AV, Wu X, Shete S. Mediating effects of smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the relation between the CHRNA5-A3 genetic locus and lung cancer risk. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3458–3462. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk JB, Chen TH, Gottlieb DJ, Walter RE, Nagle MW, Brandler BJ, Myers RH, Borecki IB, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, O’Connor GT. A genome-wide association study of pulmonary function measures in the Framingham Heart Study. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000429. e1000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk JB, Shrine NR, Loehr LR, Zhao JH, Manichaikul A, Lopez LM, Smith AV, Heckbert SR, Smolonska J, Tang W, Loth DW, Curjuric I, Hui J, Cho MH, Latourelle JC, Henry AP, Aldrich M, Bakke P, Beaty TH, Bentley AR, Borecki IB, Brusselle GG, Burkart KM, Chen TH, Couper D, Crapo JD, Davies G, Dupuis J, Franceschini N, Gulsvik A, Hancock DB, Harris TB, Hofman A, Imboden M, James AL, Khaw KT, Lahousse L, Launer LJ, Litonjua A, Liu Y, Lohman KK, Lomas DA, Lumley T, Marciante KD, McArdle WL, Meibohm B, Morrison AC, Musk AW, Myers RH, North KE, Postma DS, Psaty BM, Rich SS, Rivadeneira F, Rochat T, Rotter JI, Soler Artigas M, Starr JM, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Wijmenga C, Zanen P, Province MA, Silverman EK, Deary IJ, Palmer LJ, Cassano PA, Gudnason V, Barr RG, Loos RJ, Strachan DP, London SJ, Boezen HM, Probst-Hensch N, Gharib SA, Hall IP, O’Connor GT, Tobin MD, Stricker BH. Genome wide association studies identify CHRNA5/3 and HTR4 in the development of airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(7):622–632. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0366OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Whittington CF, Hay BA, Epton MJ, Gamble GD. Individual and cumulative effects of GWAS susceptibility loci in lung cancer: associations after sub-phenotyping for COPD. PLoS One. 2011;6(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016476. e16476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Warren L, Aponte J, Gulsvik A, Bakke P, Anderson WH, Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Pillai SG. The SERPINE2 gene is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in two large populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(2):167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1723OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.