Abstract

The majority of individuals evaluate themselves as superior to average. This is a cognitive bias known as the “superiority illusion.” This illusion helps us to have hope for the future and is deep-rooted in the process of human evolution. In this study, we examined the default states of neural and molecular systems that generate this illusion, using resting-state functional MRI and PET. Resting-state functional connectivity between the frontal cortex and striatum regulated by inhibitory dopaminergic neurotransmission determines individual levels of the superiority illusion. Our findings help elucidate how this key aspect of the human mind is biologically determined, and identify potential molecular and neural targets for treatment for depressive realism.

Keywords: positive illusion, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, sensorimotor striatum, behavioral control, hopelessness

As so eloquently stated by Lionel Tiger (1), “optimism has been central to the process of human evolution” and is important to the welfare of communities, a subjective but discrete process that should be biologically determined. A positive outlook concerning one’s own ability, personality, and future is an essential aspect of the human mind. It motivates future goals and helps us prepare for upcoming challenges. Positively evaluating the self, a concept termed the “superiority illusion,” involves judging oneself as being superior to average people along various dimensions, such as intelligence, cognitive ability, and possession of desirable traits. This concept contains a well-recognized mathematical flaw, however. Most people are not more desirable than average and do not possess most of the desirable characteristics, assuming a normal distribution of the population (2). The superiority illusion is one type of positive illusion; other types include optimism bias and illusion of control (3). Whereas the superiority illusion is specifically about one’s own abilities/characteristics, optimism bias involves one’s own future, and illusion of control involves personal control over environmental circumstances; all are considered common aspects of unrealistic favorable attitudes toward oneself and promotion for mental health (3). These positive beliefs of the human mind have attracted the attention of a wide range of investigators, including anthropologists, biologists, psychologists, clinicians, and neuroscientists.

Moderately positive illusions are important for mental health (3); negative thoughts about the self are characteristic of depression (4). One study reported that the severity of depressive symptoms is negatively correlated with optimism bias, as measured by self-estimation of one’s own possible future events (5). A recent computational model further suggested that positive illusions are evolutionarily selected (6). Given that the superiority illusion is a phylogenetically old aspect of human cognition, it can be assumed that the brain has evolved to support it.

A growing number of neuroimaging studies using functional MRI (fMRI) have identified the neural substrates of the self, including self-evaluation. It is reported that relating oneself to positive traits, but not negative traits, is associated with activation of the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), both dorsal (DMPFC) and ventral (VMPFC), as well as the supplemental motor area, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), both dorsal (dACC) and ventral (7). Moreover, activation of the dACC and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) during social-comparative judgments of self-traits is negatively associated with the degree of the superiority illusion (or “above-average effect”) (8). The dACC and OFC have a “top-down” inhibitory controlling effect on other brain regions (9), and thus also contribute to the suppression of heuristic approaches to positive self-evaluation (8). Interestingly, depressive patients reportedly exhibit increased ACC activation when attributing negative emotions to themselves (10).

The MPFC, along with the striatum, compose loops known as fronto-striatal circuits (11). A meta-analysis of 126 task-based neuroimaging studies reported coactivation between the striatum and the MPFC, including the ACC (12). In addition, recent advances in functional connectivity (FC) analyses of resting-state fMRI data (13) have provided insight into the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture in healthy individuals, as well as psychiatric patients. FC between the striatum and MPFC was observed in the healthy resting brain (14), whereas patients with depression showed resting-state hyperconnectivity in the ACC, VMPFC, putamen/pallidum, and substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area (15), the latter an origin of dopaminergic projections, implicating dopaminergic neural circuits in cognitive and affective functions.

A notable neurochemical feature of the striatum is its high density of dopamine D2 receptors, as the major receiving site of dopaminergic projections from the substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area. Individual differences in striatal D2 receptor availability have been associated with personality, mood, and psychiatric symptoms. Healthy subjects with lower D2 receptor availability, presumably due to higher presynaptic dopamine release (16), in the dorsal, but not ventral, striatum had a propensity to rate themselves as highly socially desirable (17). Self-reported social desirability is negatively associated with subjective hopelessness (18), as measured by the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (19), an index of feelings about the future, expectations, and loss of motivation. In line with these observations, there is evidence that levodopa increases positive expectations for one’s future (20). In addition, increased striatal D2 receptor availability in patients with depression is related to enhanced inhibition of motor and thought processes (21), whereas patients with addiction show low D2 receptor availability in the striatum, associated with impaired inhibitory control of impulsivity (22), indicating the critical involvement of D2 receptors in inhibitory processes (23).

Dopamine neurotransmission has an effect on frontal and striatal activations as well. The administration of D2 agonists suppresses activity in the prefrontal cortex during cognitive processing (24), and the D2 receptor genotype modulates FC strength within the default mode network and the striatum (25). Taken together, these findings suggest a possible impact of striatal dopaminergic states on resting-state fronto-striatal connectivity.

Based on the aforementioned findings from isolated PET and fMRI studies, we may speculate about the possible interrelationship among MPFC-striatal connectivity, striatal D2 receptor availability, and the superiority illusion. There is currently no direct conclusive evidence on this issue, however. In the present study, we aimed to clarify these interrelations, using resting-state fMRI and PET measurements, which examine the intrinsic functional and chemical states of the brain, respectively. This approach makes possible the elucidation of the neural mechanisms underlying the superiority illusion by uncovering the potential role of striatal D2 receptors in modulating interactions between the striatum and frontal cortex.

Results

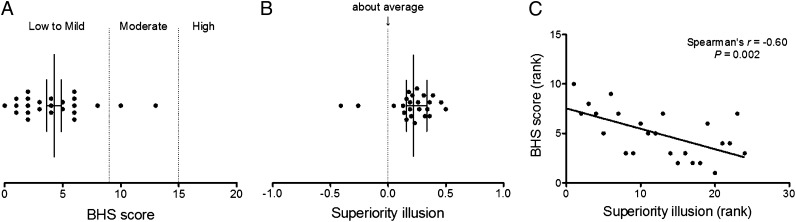

We first examined the relationship between scores on the superiority illusion task and BHS, which has been related positively to depression symptom severity (18). The majority of subjects exhibited low to mild hopelessness (median, 4.0; range, 2.0–6.0) (Fig. 1A) and a moderate level of the superiority illusion (median, 0.22; range, 0.16–0.335) (Fig. 1B). Correlation analysis revealed a negative relationship between these two measures (n = 24; r = −0.60, P = 0.002, Spearman’s rank test) (Fig. 1C). To further characterize the study subjects, we also measured trait anxiety and self-esteem using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (26) and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (27), respectively. Neither of these measures was correlated with the superiority illusion (all P > 0.05) (Table S1). These findings suggest that the superiority illusion measures belief, independent of anxiety or self-esteem.

Fig. 1.

Behavioral results. (A) BHS scores (median, 4.0; range, 2.0–6.0). (B) Superiority illusion (median, 0.22; range, 0.16–0.335). (C) Relationship between BHS and superiority illusion (r = −0.60, P = 0.002).

We then looked for resting-state FC in relation to D2 receptor availability in the dorsal striatum. For this analysis, we divided the dorsal striatum into two functional subdivisions: associative striatum (AST) and sensorimotor striatum (SMST) (Materials and Methods). In these regions, nondisplaceable binding potentials (BPND) of a PET imaging agent for D2 receptor, [11C]raclopride, which represent D2 receptor availability (Table S2), were regressed with the resting-state FC for each seed (AST and SMST, bilaterally). Our values for striatal FC (z > 2.3; cluster significance, P < 0.05 corrected; Fig. S1) are in accordance with previous reports (14). The resting-state striatal FC, which was correlated with D2 BPND in each region of interest (ROI) by application of a frontal lobe mask, is provided in Fig. S2 and Table S3 (z > 2.3; cluster significance, P < 0.05 corrected).

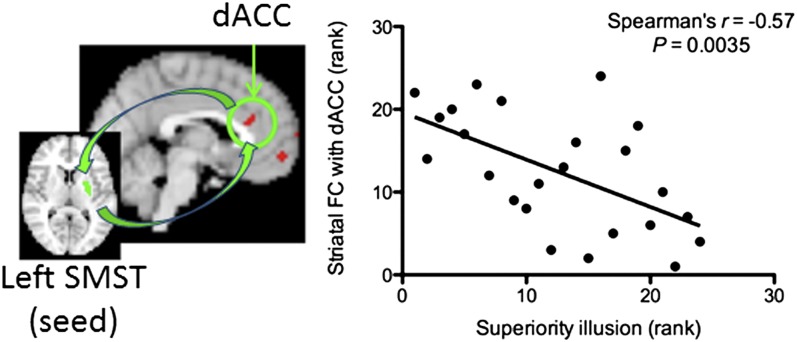

Finally, we searched the regions correlated with the superiority illusion restricted to D2 BPND-correlated striatal FCs in Table S3 with Bonferroni correction separately for each ROI, and then applied path modeling (mediation analysis) to test whether striatal D2 receptor availability leads to the superiority illusion by modulating striatal FC. We found that the superiority illusion was negatively correlated with FC between the dACC and left SMST (n = 24; r = −0.57, P = 0.0035, Spearman’s rank test) (Fig. 2), but not with FCs involving right SMST or the AST. We also tested whether the dACC-striatal FC overlapped with the results obtained when superiority illusion scores were regressed with the resting-state FC for left SMST. We confirmed that the dACC-striatal FC-correlated D2 BPND overlapped with the FC-correlated superiority illusion (z > 2.3; cluster significance, P < 0.05 corrected) (Fig. S3C). There was no significant correlation between D2 BPND in left SMST and the superiority illusion (r = −0.1, P = 0.64).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between striatal FC and superiority illusion. A significant negative relationship between left SMST FC with dACC and superiority illusion can be seen (r = −0.57, P = 0.0035).

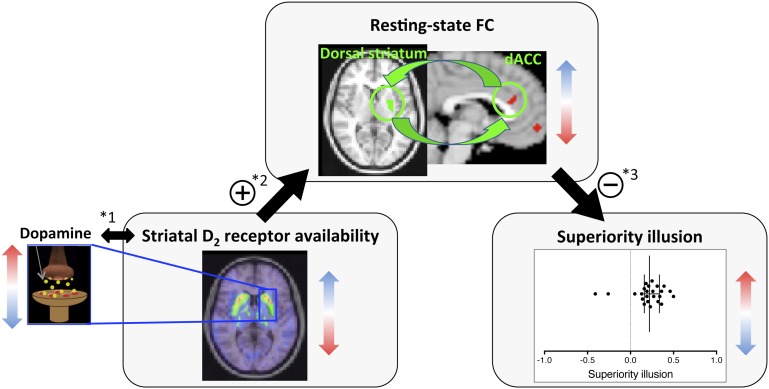

Mediation analysis based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples using bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals (28) showed a significant indirect effect of striatal D2 BPND on the superiority illusion through dACC-striatal FC [indirect effect (IE) = −0.18; SE = 0.12; lower limit (LL) = −0.56; upper limit (UL) = −0.045] (Fig. 3). Because of concerns about two outliers with negative superiority illusion scores (Fig. 1B), we applied path modeling only for those with positive superiority illusion scores (n = 22). This mediation analysis again confirmed the indirect effect through dACC-striatal FC (IE = −0.10, SE = 0.07; LL = −0.31; UL = −0.02).

Fig. 3.

Influence of striatal D2 availability on superiority illusion is mediated through dACC- striatal FC. Assuming an inverse relationship between D2 receptor availability and presynaptic dopamine release (1), dopamine likely acts on striatal D2 receptors to suppress FC between the dorsal striatum and dACC (2). This connectivity predicts individual differences in the superiority illusion (3). The indirect effect of striatal D2 receptor availability on the superiority illusion is significantly mediated through dACC-striatal FC (IE = − 0.18; SE = 0.12; LL = −0.56; UL = −0.045). “+” indicates a positive relationship; “–,” a negative relationship.

Discussion

According to fMRI studies, the SMST plays an important role in motor and cognitive planning, such as action selection in resolving stimulus–response conflict (29). PET studies have reported a close association of D2 receptor availability in the SMST with harm avoidance (30) and self-reported social desirability (17), suggesting that this region subserves these personality-related aspects of thought and behavior. Given that the dorsolateral striatum and its dopaminergic afferents support habitual or reflexive control (31), the contribution of the SMST to the superior illusion observed in the present study may reflect the habitual control of self-evaluation. Because the dACC is also the controlling site associated with more thoughtful or cognitive control (32), this region may act to control cognitively the propensity to evaluate oneself positively (8, 33). These two controllers in the brain are known to be interconnected (34), and our present findings suggest that they work together to control action selection for positive self-evaluation, which is under dopaminergic modulation.

Dopaminergic modulation of neuronal communication is crucial to normal functioning of brain circuits contributing to thought and behavior (35). Stimulation of striatal D2 receptors by dopamine likely suppresses inhibitory control by the fronto-striatal circuits over impulsive responding (23). Assuming an inverse correlation between D2 receptor availability and presynaptic dopamine release (16), this would be in agreement with our finding on the positive association of striatal D2 receptor availability with the fronto-striatal FC. Keep in mind that D2 receptor availability is also influenced by receptor density. The availability of striatal D2 receptors reportedly parallels frontal metabolic activity, a marker of brain function. Specifically, reductions in striatal D2 receptors in drug-addicted subjects who failed to demonstrate inhibitory control of impulsivity were associated with decreased metabolic activity in the OFC, ACC, and DLPFC (22). In this respect, our present results suggest that dopamine acts on striatal D2 receptors to attenuate (i.e., suppress) FC between the ACC and striatum, leading to reduced control over the superiority illusion (Fig. 3).

Although here dopamine is hypothesized to support the superiority illusion mediated through dACC-striatal FC, other molecular systems modulate FCs between striatum and prefrontal areas, including serotonin. Indeed, a recent pharamacologic study found that the antidepressant efficacy of SSRIs modulated the FC between ventral striatum and anteroventral prefrontal cortex, which is associated with the reward system (36). Networks related to depressive behavior may coexist in different loops between striatum and prefrontal areas, and thus the superiority illusion in particular might be best viewed as the products of larger-scale interactions of different loops and different molecular systems. These intertwined relationships remain to be resolved.

In conclusion, the present study provides the neuromolecular basis for the superiority illusion by demonstrating an interrelationship between dopamine neurotransmission and fronto-striatal FC. Given that the superiority illusion is negatively related to self-reported hopelessness (Fig. 1C), possession of this illusion is important to mental health, promoting positive hope for the future. Understanding the neural and molecular mechanisms behind the superiority illusion is critical for understanding the nature of the human mind and the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. The present experimental paradigm will also be applicable to patients with depression, for examining how depressive realism is related to the proposed neuromolecular mechanisms, as well as to pharmacologic intervention targeting dopaminergic modulation of the superiority illusion via fronto-striatal FC.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Twenty-four right-handed healthy male subjects (mean age, 23.5 ± 4.4 years) participated in the study. All subjects had normal or corrected vision, had no history of neurologic or psychiatric disorders, and were not taking any medications that could interfere with task performance or with PET data. The study was approved by the Ethics and Radiation Safety Committee of the National Institute of Radiological Sciences.

Procedures.

Each subject underwent both resting-state fMRI and PET scanning. Outside the scanner, each subject completed the superiority illusion task on a personal computer, as well as the BHS (19), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (26), and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (27).

Behavioral Procedures.

Stimuli and Task.

Sixty personality words obtained from Rosenberg et al. (37) were translated into Japanese. Pilot subjects (n = 14) rated social desirability for each word using a seven-point scale of −3 (very bad) to +3 (very good). The one-sample t test was applied to each word to test the significance of social desirability (better or worse). Based on statistical analyses, 52 significant words (all P < 0.005) were divided into good or bad personality traits (26 words for each category) for use in the experiment (Table S4). In the experiment outside the scanner, subjects were asked to rate how they compared themselves with the average peer on these personality traits using a visual analog scale (with scores raging from 0, below average, to 100, above average, with 50 = average). Each trial began with a fixation cross on a screen, followed by a trait word.

Analysis.

To obtain the magnitude of the superiority illusion (mean deviation from average) for each subject, ratings for negative traits were reverse-scored to collapse with ratings of positive traits. The mean deviation was obtained as a ratio for each subject and was used for correlation analyses with questionnaires and FC data, using Spearman’s rank tests in SPSS.

PET Procedures.

Data Acquisition.

All PET studies were performed with a Shimadzu SET-3000GCT/X machine (38), which provides 99 sections with an axial field of view of 26 cm. The intrinsic spatial resolution was 3.4 mm in plane and 5.0 mm FWHM axially. With a Gaussian filter (cutoff frequency, 0.3 cycle/pixel), the reconstructed in-plane resolution was 7.5 mm FWHM. Data were acquired in 3D mode. Scatter correction was provided using a hybrid scatter correction method based on acquisition with a dual-energy window setting (39). A 4-min transmission scan using a 137Cs line source was performed for correction of attenuation. For evaluation of striatal D2 receptors, a bolus of 223.4 ± 12.7 MBq of [11C]raclopride with high specific radioactivity (195.8 ± 72.8 GBq/umol) was injected i.v. from the antecubital vein with a 20-mL saline flush. Dynamic scans were performed for 60 min for [11C]raclopride and for 60 min immediately after the injection.

ROIs.

Four ROIs were selected based on the anatomic and functional subdivisions of the striatum outlined by Mawlawi et al. (40). Each ROI was traced manually on MNI152 space in the left and right AST (precommisural dorsal cudate, precommisural dorsal putamen, and postcommisural caudate), and left and right SMST (postcommisural putamen).

Data Analysis.

Quantitative analysis was performed using the three-parameter simplified reference tissue model (41). The cerebellum was used as a reference region because it has been shown to be almost devoid of D2 receptors (42). The model provides an estimation of BPND (43), which is defined by the following equation: BPND = k3/k4 = f2 Bmax/{Kd [1+Σi Fi/Kdi]}, where k3 and k4 describe the bidirectional exchange of tracer between the free compartment and the compartment representing specific binding, f2 is the “free fraction” of nonspecifically bound radioligand in brain, Bmax is the receptor density, Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the radioligand, and Fi and Kdi are the free concentration and dissociation constant of competing ligands, respectively (41). Tissue concentrations of the radioactivities of [11C]raclopride were obtained from ROIs defined on PET images of summated activity for 60 min, with reference to the individual MRIs coregistered on summated PET images and the brain atlas.

fMRI Procedures.

Data Acquisition.

Resting-state functional imaging was performed with a GE 3.0-T Excite system to acquire gradient echo T2*-weighted echoplanar images with blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast. Each volume comprised 35 transaxial contiguous slices with a slice thickness of 3.8 mm to cover almost the whole brain (flip angle, 75°; echo time, 25 ms; repetition time, 2,000 ms; matrix, 64 × 64; field of view, 24 × 24 cm; duration, 6 min, 56 s). During scanning, subjects were instructed to rest with their eyes open. A high-resolution T1-weighted magnetization-prepared gradient echo sequence (124 contiguous axial slices; 3D spoiled-GRASS sequence; slice thickness, 1.5 mm; flip angle, 30°; echo time, 9 ms; repetition time, 22 ms; matrix, 256 × 192; field of view, 25 × 25 cm) was also collected for spatial normalization and localization.

Preprocessing.

Data processing was performed using scripts provided by the 1,000 Functional Connectomes Project (www.nitrc.org/projects/fcon_1000). Preprocessing comprised slice time correction, 3D motion correction, temporal despiking, spatial smoothing (FWHM = 6 mm), mean-based intensity normalization, temporal bandpass filtering (0.009–0.1 Hz), linear and quadratic detrending, and nuisance signal removal (white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, global signal, motion parameters) via multiple regression. Registration of each subject’s high-resolution anatomic image to a common stereotaxic space (Montreal Neurological Institute 152-brain template, MNI152; 3 × 3 × 3 mm3 spatial resolution) was accomplished by two-step process, estimation of a 12-df linear affine transformation, followed by refinement of the registration using nonlinear registration, which was then applied to each subject’s functional dataset (44).

ROI and Seed Selection.

The four ROIs (left and right AST and left and right SMST) served as seeds for resting-state FC analyses. They were applied to each subject’s prewhitened 4D residuals, and a mean time series was calculated for each seed by averaging across all voxels within the seed.

Seed-Based FC Analyses.

Each subject’s 4D residual volume was spatially normalized by applying the previously computed transformation to MNI152 3-mm standard space. Then the mean time series for each seed was determined by averaging across all voxels in each seed ROI. Using these mean time series, a correlation analysis for each subject and each ROI was performed using the AFNI program 3dfim+, carried out in each individual’s native space. This analysis produced subject-level correlation maps of all voxels in the brain that were positively correlated with the seed time series. Finally, these correlation maps were converted to z-value maps using Fisher r-to-z transformation onto MNI152 3-mm standard space.

Group-Level Analyses.

Group-level analyses for each seed ROI were carried out using a mixed-effects model (FLAME) implemented in FSL flameo. In addition to the group mean vector, the model included demeaned BPND values and ages. Cluster-based statistical correction for multiple comparisons was performed using Gaussian random field theory (z > 2.3; cluster significance, P < 0.05 corrected). Given this study’s focus on the FC between frontal and striatum regions, we limited our analysis within the frontal lobe creating a frontal lobe mask by combining the frontal areas in the AAL atlas. This group-level analysis produced the thresholded Z-statistic map of voxels whose correlation with the seed ROI exhibited significant variation in association with the BPND values (i.e., frontal regions in which connectivity with the seed region was predicted by the level of striatal dopamine D2 receptor availability).

We then tested whether the observed interactions between striatal FCs and the BPND values were related to individual measures of the superiority illusion. We performed correlation analyses between striatal FCs correlated with the BPND and superiority illusion scores, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons separately for each ROI. To verify the findings obtained, we performed cluster-based statistical analysis using Gaussian random field theory within the frontal lobe, including demeaned superiority illusion scores in the model (z > 2.3; cluster significance, P < 0.05 corrected). Finally, we tested the indirect effect of BPND on the superiority illusion through striatal FCs using path modeling (mediation analysis), which was estimated based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples using bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals (28), with D2 receptor availability as an independent variable, the superiority illusion as a dependent variable, and FC as a mediator.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Camerer for valuable comments, Y. Kasama for help with programming, K. Suzuki and I. Izumida for assistance as clinical research coordinators, members of the Clinical Imaging Team for support with PET scans, and members of Molecular Probe Program for [11C]raclopride. This study was supported in part by the “Integrated Research on Neuropsychiatric Disorders” study carried out under the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1221681110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tiger L. Optimism: The Biology of Hope. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers JR, Windschitl PD. Biases in social comparative judgments: The role of nonmotivated factors in above-average and comparative-optimism effects. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(5):813–838. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(2):193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck A. Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. New York: Harper & Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strunk DR, Lopez H, DeRubeis RJ. Depressive symptoms are associated with unrealistic negative predictions of future life events. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(6):861–882. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson DDP, Fowler JH. The evolution of overconfidence. Nature. 2011;477(7364):317–320. doi: 10.1038/nature10384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moran JM, Macrae CN, Heatherton TF, Wyland CL, Kelley WM. Neuroanatomical evidence for distinct cognitive and affective components of self. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18(9):1586–1594. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.9.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beer JS, Hughes BL. Neural systems of social comparison and the “above-average” effect. Neuroimage. 2010;49(3):2671–2679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron. 2011;69(4):680–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimm S, et al. Increased self-focus in major depressive disorder is related to neural abnormalities in subcortical-cortical midline structures. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(8):2617–2627. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tekin S, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry: An update. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(2):647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postuma RB, Dagher A. Basal ganglia functional connectivity based on a meta-analysis of 126 positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging publications. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(10):1508–1521. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(4):537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Martino A, et al. Functional connectivity of human striatum: A resting-state FMRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(12):2735–2747. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alcaro A, Panksepp J, Witczak J, Hayes DJ, Northoff G. Is subcortical-cortical midline activity in depression mediated by glutamate and GABA? A cross-species translational approach. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(4):592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito H, et al. Relation between presynaptic and postsynaptic dopaminergic functions measured by positron emission tomography: Implication of dopaminergic tone. J Neurosci. 2011;31(21):7886–7890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6024-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egerton A, et al. Truth, lies or self-deception? Striatal D(2/3) receptor availability predicts individual differences in social conformity. Neuroimage. 2010;53(2):777–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole DA. Hopelessness, social desirability, depression, and parasuicide in two college student samples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(1):131–136. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42(6):861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharot T, Shiner T, Brown AC, Fan J, Dolan RJ. Dopamine enhances expectation of pleasure in humans. Curr Biol. 2009;19(24):2077–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer JH, et al. Elevated putamen D(2) receptor binding potential in major depression with motor retardation: An [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1594–1602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Telang F. Overlapping neuronal circuits in addiction and obesity: Evidence of systems pathology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1507):3191–3200. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O’Reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: Cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science. 2004;306(5703):1940–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.1102941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimberg DY, Aguirre GK, Lease J, D’Esposito M. Cortical effects of bromocriptine, a D-2 dopamine receptor agonist, in human subjects, revealed by fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;12(4):246–257. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200104)12:4<246::AID-HBM1019>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambataro F, et al. DRD2 genotype-based variation of default mode network activity and of its relationship with striatal DAT binding. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(1):206–209. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs JA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balleine BW, O’Doherty JP. Human and rodent homologies in action control: Corticostriatal determinants of goal-directed and habitual action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):48–69. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J-H, et al. Association of harm avoidance with dopamine D2/3 receptor availability in striatal subdivisions: A high-resolution PET study. Biol Psychol. 2011;87(1):164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Packard MG, Knowlton BJ. Learning and memory functions of the basal ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:563–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owen AM. Cognitive planning in humans: Neuropsychological, neuroanatomical and neuropharmacological perspectives. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;53(4):431–450. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Martino B, Kumaran D, Seymour B, Dolan RJ. Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. Science. 2006;313(5787):684–687. doi: 10.1126/science.1128356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montague PR, Hyman SE, Cohen JD. Computational roles for dopamine in behavioural control. Nature. 2004;431(7010):760–767. doi: 10.1038/nature03015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abler B, Grön G, Hartmann A, Metzger C, Walter M. Modulation of frontostriatal interaction aligns with reduced primary reward processing under serotonergic drugs. J Neurosci. 2012;32(4):1329–1335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5826-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg S, Nelson C, Vivekananthan PS. A multidimensional approach to the structure of personality impressions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1968;9(4):283–294. doi: 10.1037/h0026086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto K, et al. Performance characteristics of a new 3-dimensional continuous-emission and spiral-transmission high-sensitivity and high-resolution PET camera evaluated with the NEMA NU 2-2001 standard. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(1):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishikawa A, et al. Nuclear Science Conference Symposium Record. New York: Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers; 2005. Implementation of on-the-fly scatter correction using dual-energy window method in continuous 3D whole body PET scanning; pp. 2497–2500. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mawlawi O, et al. Imaging human mesolimbic dopamine transmission with positron emission tomography, I: Accuracy and precision of D(2) receptor parameter measurements in ventral striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21(9):1034–1057. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4(3 Pt 1):153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farde L, Hall H, Pauli S, Halldin C. Variability in D2-dopamine receptor density and affinity: A PET study with [11C]raclopride in man. Synapse. 1995;20(3):200–208. doi: 10.1002/syn.890200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Innis RB, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(9):1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersson JLR, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. Non-linear registration, a.k.a. spatial normalization. 2007. FMRIB Technical Report TR07JA2. Available at www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/analysis/techrep. Accessed January 29, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.