Abstract

Background

Although several reports have been published showing prenatal ethanol exposure is associated with alterations in N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit levels and, in a few cases, subcellular distribution, results of these studies are conflicting.

Methods

We used semi-quantitative immunoblotting techniques to analyze NMDA receptor NR1, NR2A, and NR2B subunit levels in the adult mouse hippocampal formation isolated from offspring of dams who consumed moderate amounts of ethanol throughout pregnancy. We employed subcellular fractionation and immunoprecipitation techniques to isolate synaptosomal membrane- and postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95)-associated pools of receptor subunits.

Results

We found that, compared to control animals, fetal alcohol-exposed (FAE) adult mice had: (i) increased synaptosomal membrane NR1 levels with no change in association of this subunit with PSD-95 and no difference in total NR1 expression in tissue homogenates; (ii) decreased NR2A subunit levels in hippocampal homogenates, but no alterations in synaptosomal membrane NR2A levels and no change in NR2A-PSD-95 association; and (iii) no change in tissue homogenate or synaptosomal membrane NR2B levels but a reduction in PSD-95-associated NR2B subunits. No alterations were found in mRNA levels of NMDA receptor subunits suggesting that prenatal alcohol-associated differences in subunit protein levels are the result of differences in post-transcriptional regulation of subunit localization.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that prenatal alcohol exposure induces selective changes in NMDA receptor subunit levels in specific subcellular locations in the adult mouse hippocampal formation. Of particular interest is the finding of decreased PSD-95-associated NR2B levels, suggesting that synaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptor concentrations are reduced in FAE animals. This result is consistent with various biochemical, physiological, and behavioral findings that have been linked with prenatal alcohol exposure.

Keywords: NMDA Receptor, Prenatal Alcohol, Hippocampus, NR2A, NR2B

Alcohol ingestion during pregnancy, even in moderate amounts, can affect normal brain development, resulting in changes in brain functioning that can persist throughout life. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is a term used to describe the wide range of clinical disorders, ranging from moderate to severe, that can occur in an individual whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. Investigations on the mechanisms that underlie the learning and memory impairments associated with FASD have focused on numerous processes, including glutamatergic neurotransmission. One class of glutamate receptors, the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, have received considerable attention because the levels and subcellular localization of these receptors impact the cellular processes underlying learning and memory, as well as various forms of synaptic plasticity (Gardoni et al., 2009; Tang et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2005). Several studies have found that NMDA receptors are significantly affected by prenatal alcohol exposure (see Table 1 and Costa et al., 2000a, for review). In particular, researchers have focused on NMDA receptors in the hippocampal formation, as this area of the brain has been shown to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of fetal alcohol exposure and is known to be densely populated with NMDA receptors (Berman and Hannigan, 2000). For example, prenatal alcohol exposure has been shown to decrease NMDA-sensitive glutamate binding sites in the hippocampus of 45-day-old rats (Savage et al., 1991) and alter [3H]MK-801 binding in the hippocampus of rats and guinea pigs (Abdollah and Brien, 1995; Diaz-Granados et al., 1997; Naassila and Daoust, 2002).

Table 1.

Summary of Literature Determining the Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure on NMDA Receptor Subunit Expression

| Ethanol paradigm | BEC | Animal studied | Tissue | Result (protein unless noted) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral administration (4 g EtOH/kg GD2-67) | 327 mg/dl (maternal) | Adult Dunkin Hartley guinea pigs | Cerebral cortex post nuclear fraction | ↓NR2B PND 61 | Dettmer et al., 2003 |

| Oral administration (4 g/kg maternal body weight/d) | 283 mg/dl (maternal) | Dunkin Harley guinea pig (GD 63 neonate) | CA1, CA3 fields of hippocampus | ↑NR1 mRNA | Iqbal et al., 2006 |

| Ip injection (25% EtOH on GD8) | Not determined | Adult C57Bl/6 mice | Whole brain | ↓NR2B mRNA ↑NR2A mRNA | Toso et al., 2005 |

| EtOH drinking solution (10% EtOH) | 86 to 112 mg/dl (maternal) | Sprague–Dawley pups | Hippocampus | ↑NR1 isoforms mRNA PND7,14 | Naassila and Daoust, 2002 |

| EtOH drinking solution (10% EtOH) | 86 to 112 mg/dl (maternal) | Sprague–Dawley PND 60 & 90 | Hippocampus, cerebellum, striatum, thalamus | ↓NR1 mRNA | Barbier et al., 2008 |

| Prenatal & postnatal (5 g EtOH/kg prenatal, 6.2 g EtOH/kg postnatal) | 95 mg/dl (maternal) 350 mg/dl (pup) | Sprague–Dawley pups | Hippocampus crude membrane fraction | ↑NR2A PND 10No effect other subunits | Nixon et al., 2004 |

| Liquid ethanol diet (20 to 36% EtOH) | 119 to 138 mg/dl (maternal) | Sprague–Dawley pups | Hippocampus & forbrain crude membrane fraction | No effect NR1↓NR2A forebrain PND14 ↓NR2B PND7 (hipp) & PND14 (forebrain) | Hughes et al., 1998 |

| Liquid ethanol diet (2 to 5% EtOH) | 80 mg/dl (maternal) | Sprague–Dawley neonates | Hippocampal neuronal cultures | No effect on subunits | Costa et al., 2000b |

| Liquid ethanol diet (20 to 36% EtOH) | 120 to 145 mg/dl (maternal) | Sprague–Dawley pups | Cerebral cortices membrane fraction | No effect NR1IP PSD-95: ↓C2′ NR1 & NR2ANo effect IP PSD-95 - NR2B | Honse et al., 2003 |

| Liquid ethanol diet (20 to 36% EtOH) | 148 mg/dl (maternal) | Sprague–Dawley pups | Forebrain crude membrane fraction | No effect on IP PSD-95-NR2B | Hughes et al., 2001 |

| Liquid ethanol diet (6.5% EtOH) | 133 mg/dl (maternal) | Long-Evans adults | Barrel field cortex | ↓NR1, NR2A, NR2B PND90 | Rema and Ebner, 1999 |

| Vapor chamber (39.8 mg ethanol/1 air on PND 4-9) | 330 mg/dl (pup) | Wistar pups PND10 | Cortex | No effect on NR1, NR2A or NR2B | Bellinger et al., 2002 |

NMDA receptors are ion channels that exist as heteromeric complexes composed of mandatory NR1 and modulatory NR2 (A-D) or NR3 (A, B) subunits. The NMDA receptor NR1 subunit is essential to the formation of a functional receptor (Paoletti and Neyton, 2007). Of the modulatory subunits, NR2A and NR2B are the most highly expressed forms in the adult rodent hippocampus (Al-Hallaq et al., 2007; Wenzel et al., 1997); NR3A is also present in the rodent hippocampus, but at much lower levels than NR2A and NR2B in the adult (Al-Hallaq et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2002).

NMDA receptors are localized both within the synapse and extrasynaptically (Harris and Pettit, 2007; Lau and Zukin, 2007). While the overall function of an individual NMDA receptor is dependent on its subunit composition (Yashiro and Philpot, 2008), the location of the receptor governs its coupling to specific intracellular signaling pathways (Hardingham, 2006); the balance between synaptic and extrasynaptic receptor activation shapes the overall cellular response. Even though both synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors mediate Ca2+ influx, studies show that extrasynaptic receptors are mainly activated under conditions of high concentrations of NMDA (or glutamate) and mediate opposing effects on intracellular signaling pathways compared to those produced by synaptic NMDA receptors (Chandler et al., 2001; Ivanov et al., 2006; Mulholland et al., 2008). Synaptic NMDA receptors are organized and spatially restricted in large macromolecular signaling complexes called postsynaptic densities (PSDs) within the synaptic membrane (Lau and Zukin, 2007). PSD-95, a member of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family, is an anchoring and essential synaptic adapter protein, not found extrasynaptically, that targets the NMDA receptor NR2A and NR2B subunits to the PSD (Al-Hallaq et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2006; Hughes et al., 2001). Although there is evidence that the NR1 C2′ cassette contains a motif allowing it to associate with PSD-95, NR1 is generally not considered to bind to PSD-95 (Honse et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2002). This complex of PSD-95 and NMDA receptors has been implicated in the regulation of several cellular processes, including synaptic plasticity and learning and memory (Chen et al., 2006; Gardoni et al., 2009).

Studies employing a variety of prenatal and neonatal alcohol exposure paradigms have yielded conflicting results regarding the effects of the exposure on NMDA receptor subunit composition (Table 1). It is also of note that most of these studies have employed relatively young animals and, in general, have not assessed the subcellular localization of the NMDA receptor subunits. It is important to determine whether such alterations in NMDA receptor subunit levels or localization exist in adult animals that were prenatally exposed to alcohol in order to determine if there is an association between these alterations and the life-long cognitive impairments observed in FASD. The current study aimed to test the hypothesis that moderate prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with differential NMDA receptor subunit expression and/or subcellular localization in adult animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethanol Drinking Paradigm

All of the procedures involving animals that were used in the current studies were approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to NIH guidelines.

The ethanol drinking paradigm was carried out as previously described (Samudio-Ruiz et al., 2009). Briefly, C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, MA) female mice were given a two-bottle choice paradigm, in which water and either 0.066% (w/v) saccharin-sweetened 5%ethanol solution or 0.066% (w/v) saccharin-sweetened water (Sacc) as a control were available 24-h/d prior to and during pregnancy. The volumes of each solution drunk were measured every other day and replaced with fresh solution as necessary. The average g ethanol consumed/kg body weight/d were calculated for each dam during pregnancy. After the litters were born, dams were weaned off the ethanol and saccharin solutions by decreasing concentrations by one-half every other day until dams were drinking only water.

mRNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Primers

mRNA was isolated from dissected hippocampal formation using the Oligotex Direct mRNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stored at −80°C prior to use. The mRNA concentration was measured (OD 260 nm) using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). cDNA synthesis reactions were performed using 10 ng mRNA, as described in Caldwell and colleagues (2008). Oligonucleotide sequences specific for mouse NMDA NR1, NR2A, NR2B subunits and for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1), which was used as an internal standard, were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The specificity of each primer pair was confirmed by the identification of a single PCR product of predicted size on agarose gels followed by sequencing of the excised band. DNA sequencing was performed by the UNM Proteomic and Molecular Biology Core facility.

Semi-Quantitative Determination of Transcript Levels by Real Time-PCR

Real time semi-quantitative PCR was performed as described in Caldwell and colleagues (2008). The relative quantification of the target gene was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method of Livak and Schmittgen (2001), as described in Caldwell and colleagues (2008).

Immunoblotting of NMDA Receptor Subunits in Hippocampal Homogenates

NMDA receptor subunit protein expression was analyzed in whole hippocampal homogenates. Briefly, hippocampal tissue from adult saccharin control (Sacc) and fetal alcohol-exposed (FAE) mice (2 to 5 months old) was homogenized in homogenization buffer (HB) containing (in mM) 20 Tris, pH 7.4, 1.0 EDTA, 320 sucrose, 20 sodium pyrophosphate, 10 sodium fluoride, 20 β-glycerophosphate, and 0.2 sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Total protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Protein Assay solution (Bradford method) with bovine albumin serum (BSA) as a standard. Samples were stored at −80°C.

Samples were thawed on ice and NuPAGE 4× sample buffer (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) was added. Samples were then heated at 70°C for 10 minutes and equal protein amounts were loaded onto NuPage 4 to 12% Bis-Tris pre-cast gels (Invitrogen) before transfer to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked in 0.25% I-block (Tropix; Applied Biosystems) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris, pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 (Bio-Rad Laboratories), then probed with anti-NR2A or anti-NR2B rabbit polyclonal antibodies at 1:1,000 (PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO), or with anti-NMDAR (NR1) mouse monoclonal antibody at 1.5 μg/ml (Upstate/Millipore, Billerica, MA), which recognizes all NR1 isoforms. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For each sample, the anti-NMDA receptor subunit immunoreactivity was normalized to the anti-β-actin immunoreactivity (rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1:2,000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), which was detected with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Pierce). We verified that β-actin levels were not altered by prenatal alcohol exposure by comparing anti-β-actin immunoreactivities in Sacc and FAE hippocampal formation to those of a second “standard” protein, cyclophillin A (rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1:2,000; Upstate), in the same sample (data not shown). PSD-95 expression was determined using a rabbit polyclonal anti-PSD-95 antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling) and detected with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Pierce). PSD-95 values were also normalized to β-actin. Immunoreactivities were amplified using Pierce Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescence and captured on film. Optical density values were obtained using the Quantity One program (Bio-Rad).

Synaptosomal Membrane (LP1) Preparation and Immunoblotting of NMDA Receptor Subunits

Subcellular fractionation was performed using described protocols (Dunah and Standaert, 2001; Grosshans et al., 2002; Huttner et al., 1983). Briefly, brains from adult Sacc and FAE mice (2 to 5 months old) were rapidly removed following decapitation and the hippocampal formation was isolated by dissection. Hippocampal tissue was homogenized in a glass-glass Dounce homogenizer (5 down-up strokes each with a loose- and a tight-fitting pestle) in subcellular fraction homogenization buffer (SF-HB) containing (in mM) 10 Tris, pH 7.4, 320 Sucrose, 5 NaF, 1 EDTA, 1 EGTA, 1 Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). The homogenate was centrifuged (1,000 × g, 6 minutes, 4°C) to remove nuclei and large debris (P1 fraction). The supernatant (S1 fraction) was then centrifuged (10,000 × g, 15 minutes, 4°C) to obtain a crude synaptosomal fraction (P2 fraction). The P2 fraction was hypo-osmotically lysed with ice-cold deionized water containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and subjected to homogenization 3 times with a Teflon®-coated, spinning pestle (3000 rpm). HEPES-NaOH buffer (pH 7.4) was then added to the resulting P2 lysate to a final concentration of 7.5 mM and kept on ice for 30 minutes before being centrifuged (25,000 × g, 20 minutes, 4°C) to yield a lysate pellet (LP1 fraction) and a lysate supernatant (LS1 fraction). The LP1 fraction, which is a plasma-membrane enriched synaptosomal membrane fraction, was resuspended in SF-HB after discarding the LS1 fraction. Total protein concentrations were determined for LP1 fractions as described above.

In order to characterize the enrichment of the LP1 fraction in plasma membrane proteins, the relative imunoreactivities of anti-N-cadherin (1:500; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), a plasma membrane protein, and anti-calnexin (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein, were compared in LP1 and starting (S1) fractions by immunoblotting. Preliminary experiments determined the linear immunoreactivity range for both proteins. The fold enrichment was calculated by dividing the optical density of the anti-N-cadherin and anti-calnexin bands in the LP1 fraction by their optical densities in the S1 fraction. The fold enrichment for N-cadherin was approximately 2.5 to 3 times greater than the fold enrichment for calnexin, demonstrating that the LP1 fractions were enriched in plasma membranes relative to ER membranes. Previous studies have found that calnexin, while mainly present in intracellular pools, is also present in extrasynaptic membranes (Goebel-Goody et al., 2009). This finding is consistent with the fact that calnexin was found in our LP1 preparations, which are believed to contain synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes.

LP1 samples were thawed on ice and NMDA receptor NR1, NR2A, and NR2B subunit levels were determined by immunoblotting, as described above using rabbit polyclonal anti-NR2A, anti-NR2B (PhosphoSolutions) and anti-NR1 mouse monoclonal (Upstate/Millipore) antibodies followed by appropriate secondary antibodies (Pierce). Anti-PSD-95 (Cell Signaling) immunoreactivity was used to normalize NMDA receptor subunit immunoreactivities in surface receptor studies. Blots were stripped, as needed, according to manufacture’s protocol, using Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce).

Hippocampal Tissue Preparation for Immunoprecipitation

Hippocampi from adult mice were homogenized in HB (see above, except pH 7.7). The nuclear pellet was removed from the homogenate by centrifugation (1,000 × g, 6 minutes, 4°C) and the total protein concentration of the postnuclear fraction was determined as described above. 700 μg of the postnuclear fraction were treated as previously reported by Al-Hallaq and colleagues (2007) in 1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholic acid (DOC) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 45 minutes at 37°C followed by centrifugation (100,000 × g, 60 minutes, 4°C). The DOC-soluble material was pre-cleared with 75 μl (packed volume) of protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (GE Healthcare BioScience Corp., Piscataway, NJ) for 1 hour at 4°C to remove proteins which nonspecifically bind to the protein A-Sepharose beads.

The procedure for the immunoprecipitation of anti-PSD-95 immune complexes was based on the previously reported method of Furuyashiki and colleagues (1999) using 2.0 μl of a mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 6G6-1C9) obtained from Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO). Tissue and antibody were incubated overnight at 4°C with mixing. This was followed by further incubation with protein A-Sepharose CL-4B (25 μl packed beads) for 1 hour at 4°C with mixing. Mouse IgG2a (Affinity Bioreagents) was used as a negative control. Beads were collected by centrifugation (1,000 × g, 2 minutes, 4°C) and washed twice with ice-cold HB. Subsequently, the beads were boiled with 20 μl of NuPAGE sample loading buffer (Invitrogen) for 5 minutes to elute the bound material. Samples were electrophoresed on NuPAGE 3 to 8%Bis-Tris pre-cast gels (Invitrogen), as described above. Membranes were probed with antibodies to NMDA receptor subunits NR2A and NR2B(PhosphoSolutions), as well as an antibody to PSD-95 (Cell Signaling), as described above. Blots were then stripped and re-probed with a mouse monoclonal anti-NR1 antibody (Upstate/Millipore) as described above. Analysis of NMDA receptor subunits (NR2A, NR2B, and NR1) associated with anti-PSD-95 immunoprecipitates were normalized to the anti-PSD-95 immunoreactivity optical density values obtained for each sample; negative control (mouse IgG2a) optical density values were subtracted from each sample.

Sample Collection and Data Analysis

All samples were taken from both male and female adult mice. Roughly equal male and female mice were used for all experiments and no significant gender effects were noted. To eliminate litter effects, only 1 animal was used from each litter.

In order to compare immunoreactivities across multiple gels, optical densities of all bands on a gel were normalized to the immunoreactivity present in a 1,000 × g postnuclear hippocampal standard preparation or a LP1 standard preparation (for synaptosomal membrane experiments) run on the same gel. Data were graphed and analyzed using GraphPad 3.0/4.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) program using ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. Standard unpaired t-test was also used, when applicable. All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Fetal Alcohol Exposure Paradigm

A voluntary drinking, two-bottle choice, fetal alcohol exposure paradigm was employed as previously described (Samudio-Ruiz et al., 2009). Animals were taken from litters born to dams having an average maternal consumption of 9.20 (±2.37) g ethanol/kg body weight/d. We previously reported that this paradigm yielded maternal blood ethanol concentrations of 78 mg/dl (n = 7) in dams having an average daily consumption of 8.0 g ethanol/kg body weigh/d (Caldwell et al., 2008). As previously reported (Caldwell et al., 2008; Allan et al., 2003), we found no significant differences between Sacc and FAE maternal weights or litter sizes (Table 2). Additionally, we found no difference in the female:male ratio of the litter (Table 2).

Table 2.

Maternal/Neonatal Parameters for Animals in This Study

| Prenatal diet | Maternal weight before drinking paradigm (g) | Maternal weight day 6–7 after birth (g) | Litter size (total) | Litter size (female) | Litter size (male) | g EtOH/kg body weight/d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharin (Sacc) | 20.97 (±2.63) | 29.91 (±2.22) | 5.9 (±2.28) | 2.9 (±1.54) | 3.0 (±1.59) | – |

| Ethanol (FAE) | 20.88 (±3.38) | 28.82 (±2.70) | 6.2 (±2.05) | 3.0 (±1.63) | 3.2 (±1.59) | 9.20 (±2.37) |

Hippocampal NMDA Receptor Subunit mRNA and Protein Levels

We assessed mRNA levels of the NMDA receptor NR1, NR2A, and NR2B subunits in Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples and found no significant differences between the 2 groups (data not shown). For these studies, we used HPRT1 as an internal control, which had previously been validated as an appropriate internal standard for Real Time PCR in our FAE model (Caldwell et al., 2008).

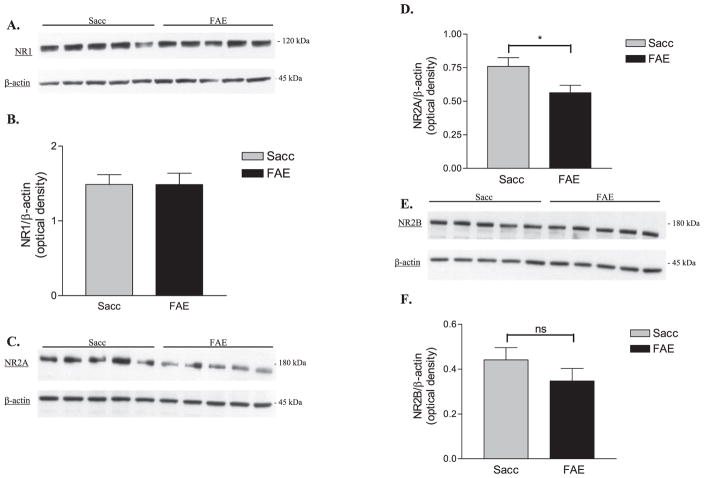

We also measured the protein levels of the NMDA receptor NR1, NR2A, and NR2B subunits in Sacc and FAE hippocampal formation homogenates using immunoblotting techniques. No significant difference between NR1 (Figs. 1A,B) levels was obtained in FAE and Sacc samples, whereas we found a significant decrease in NR2A protein levels [t(16) = 2.305, p < 0.05] in the FAE group (Figs. 1C,D). We also found no significant difference in NR2B (Figs. 1E,F) levels between Sacc and FAE samples.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of total NMDA receptor subunits NR1 (n = 10), NR2A (n = 9), and NR2B (n = 9) in saccharin control (Sacc) and fetal alcohol-exposed (FAE) adult hippocampal tissue homogenates. (A) Representative Western blots for NR1 and β-actin in Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples. (B) Normalized optical density of anti-NR1 immunoreactivity in Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples. (C) Representative Western blots for NR2A and β-actin in Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples. (D) Normalized optical density of anti-NR2A immunoreactivity; significant decrease in FAE [t(16) = 2.305, *p < 0.05] NR2A subunit levels. (E) Representative Western blots for NR2B & β-actin in Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples. (F) Normalized optical density of anti-NR2B immunoreactivity. There was no significant (ns) difference between Sacc and FAE in NR2B levels. All data were expressed as the optical density of the anti-NMDA receptor subunit immunoreactive band normalized to the optical density of the anti-β-actin immunoreactive band.

Synaptosomal Membrane NMDA Receptor Expression

NMDA receptor subunits have been shown to be present in several subcellular locations, including synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes, and intracellular sites, such as the ER (Al-Hallaq et al., 2007; Lau and Zukin, 2007). The preceding measurements of NMDA receptor subunit protein levels were conducted using unfractionated tissue homogenates and, thus, did not distinguish between subcellular pools of NMDA receptors. Therefore, we sought to perform our analyses of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on NMDA receptor expression in a more defined preparation, with the aim of assessing synaptosomal membrane levels of receptor subunits. Although other techniques (e.g., cross-linking and chymotrypsin treatment) have been employed to study the surface expression of receptors, we chose to use a subcellular fractionation technique (see Methods), as it provides a more direct assay of membrane-associated receptors (Dunah and Standaert, 2001; Goebel-Goody et al., 2009; Grosshans et al., 2002; Huttner et al., 1983).

Prior to initiating our studies of NMDA receptor subunit levels, it was necessary to identify an acceptable loading control for each immunoblot. We sought a protein that was specifically associated with plasma membranes and, thus, chose PSD-95, based on its reported localization to the postsynaptic density (Lau and Zukin, 2007) and our plan to assess the association of NMDA receptor subunits with this protein (see below). We found no difference between total PSD-95 levels in LP1 fractions isolated from Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples (data not shown), and, thus, used it to normalize samples in our analyses of NMDA receptor levels.

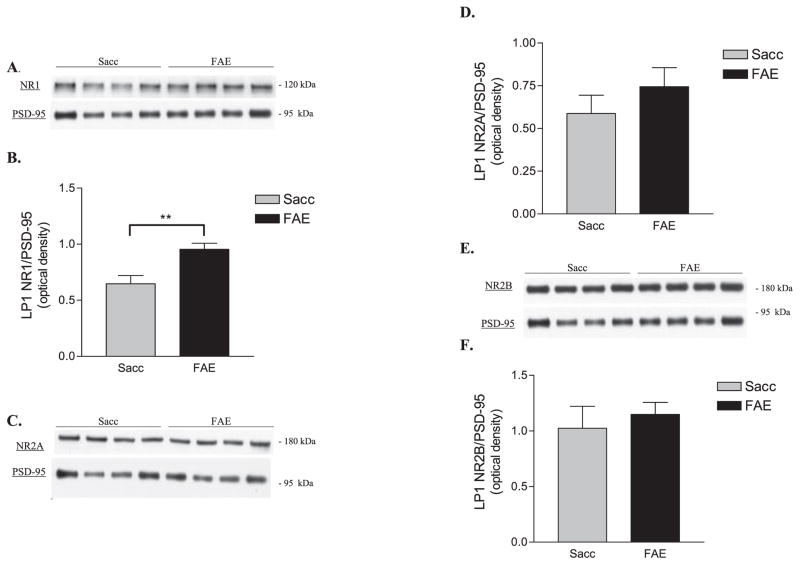

Optical densities for anti-NR1, anti-NR2A, and anti-NR2B immunoreactivities were normalized to the anti-PSD-95 immunoreactivity present in the sample. Representative blots of NR1, NR2A, NR2B, and corresponding PSD-95 blots for Sacc and FAE LP1 samples are shown in Figs. 2A,C,E respectively. Synaptosomal membraneNR1 expression in FAE samples was shown to be significantly increased compared to controls [t(10) = 3.40, **p < 0.01, n = 6] (Figs. 2A,B), whereas the levels of NR2A and NR2B were not found to be significantly different between the 2 groups (Figs. 2C–F).

Fig. 2.

Synaptosomal membrane expression of NMDA receptor subunits in saccharin control (Sacc) and fetal alcohol-exposed (FAE) LP1 fractions. (A) Representative Western blots of NR1 and corresponding postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95) in Sacc (n = 6) and FAE (n = 6) LP1 samples. (B) NR1 levels in FAE LP1 samples were significantly increased compared to controls [t(10) = 3.40, **p < 0.01]. (C) Representative Western blot of NR2A and corresponding PSD-95 in Sacc and FAE LP1 samples. (D) No significant difference between Sacc (n = 6) and FAE (n = 6) levels of surface NR2A. (E) Representative Western blot of NR2B and corresponding PSD-95 in Sacc and FAE LP1 samples. (F) No difference in NR2B expression between groups (n = 6). All data expressed relative to level of anti-PSD-95 immunoreactivity in each LP1 sample.

Immunoprecipitation of PSD-95 and Evaluation of Associated NMDA Receptors

The LP1 fraction that we employed for the previous studies contains both synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors (Goebel-Goody et al., 2009). Therefore, in order to study a synaptic population of NMDA receptors, we assessed receptor subunits associated with anti-PSD-95 immune complexes. Honse and colleagues (2003) had previously described the use of this method to study postsynaptic NR1 splice variants and NR2 subunits in cerebral cortices.

Several groups have shown that NMDA receptors and PSD-95 display limited detergent solubility (Abulrob et al., 2005; Al-Hallaq et al., 2007; Blahos and Wenthold, 1996). NMDA receptors have been shown to be partially soluble in 1% (w/v) deoxycholate (DOC) and this solubility decreases as the animal ages (Al-Hallaq et al., 2007). We evaluated the solubility of NR1, NR2A, NR2B, and PSD-95 in adult Sacc and FAE hippocampal postnuclear, soluble fractions treated with 1% DOC. We found that the percentages of NR2A and NR2B that were soluble in 1% DOC (NR2A: 17.0 ± 4.0% Sacc and 20.2 ± 7.8% FAE; NR2B:17.3 ± 7.1% Sacc and 17.8 ± 8.4% FAE) were slightly less than those reported for P42 rat hippocampus by Al-Hallaq and colleagues (2007). However, NR1 solubility (39.7 ± 19.0% for Sacc and 43.2 ± 11.0% for FAE) was similar to that previously reported (Al-Hallaq et al., 2007; Blahos and Wenthold, 1996). Takagi and colleagues (2000) reported that approximately 75% of rat hippocampal P2 fraction PSD-95 is soluble in 1% DOC; we found that 11.4 ± 3.5% of Sacc PSD-95 and 15.8 ± 2.2% of FAE PSD-95 were solubilized by 1% DOC. Although there were slight differences between the solubilities of NMDA receptor subunits and PSD-95 in Sacc and FAE samples, these differences were not statistically significant.

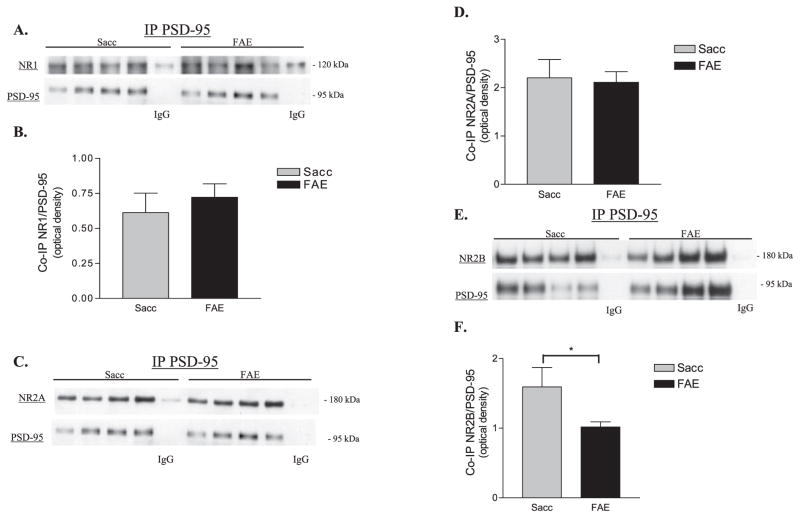

Representative Western blots and data obtained for anti-NR1, anti-NR2A, anti-NR2B and anti-PSD-95 immunoreactivities associated with anti-PSD-95 immune-complexes are shown in Figs. 3A–F. Our data demonstrate that there was not a significant difference in the amount of NR1 (Fig. 3A,B) or NR2A (Fig. 3C,D) subunits that co-immunoprecipitated with PSD-95 in Sacc and FAE samples. Due to unequal sample size (Sacc n = 14, FAE n = 13) and unequal variance between the groups, ANOVA was used to assess whether the decrease in the levels of NR2B that co-immunoprecipitated with PSD-95 in FAE samples was significantly less than that in Sacc samples [F(1,24) = 6.510, *p < 0.02] (Fig. 3E,F). Although we did observe some variability in the amount of anti-PSD-95 immunoreactivity that was associated with the immunecomplex in the immunoprecipitation experiments (see Figs 3A,C,E), we suggest that this is attributed to variance in the solubility of PSD-95 and demonstrates the importance of normalizing the anti-NMDA receptor subunit immunoreactivities to the amount of anti-PSD-95 immunoreactivity that was present in the immunoprecipitate.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95)-associated NMDA subunits in saccharin (Sacc) and fetal alcohol-exposed (FAE) hippocampal homogenates. (A) Representative Western blots of NR1 subunits that co-immunoprecipitated with PSD-95 in Sacc and FAE samples; PSD-95 levels in the corresponding samples are also shown. (B) PSD-95-associated NR1 levels in Sacc and FAE hippocampus (Sacc n = 12, FAEn = 11). No significant difference in NR1 was found between the groups. (C) Representative Western blots of anti-NR2A immunoreactivity that co-immunoprecipitated with PSD-95 in Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples; PSD-95 levels in the corresponding samples are also shown. (D) PSD-95-associated NR2A subunits (Sacc n = 13, FAE n = 14). (E) Representative Western blots of anti-NR2B immunoreactivity associated with anti-PSD-95 immunoprecipitates isolated from Sacc and FAE hippocampal samples; PSD-95 levels in the corresponding samples are also shown. (F) PSD-95-associated NR2B subunits (Sacc n = 14, FAE n = 13). ANOVA revealed a significant effect of prenatal diet [F(1,24) = 6.510, *p < 0.02]. In panels A, C, E the lanes labeled IgG were a pooled Sacc or FAE sample incubated with mouse IgG2a and served as the negative control, which was subtracted from the corresponding experimental optical densities. All NMDA receptor subunit data are expressed relative to the level of PSD-95 present within each immunoprecipitated sample (i.e., the same lane was probed for both anti-PSD-95 and anti-NMDA receptor subunit immunoreactivities).

DISCUSSION

The present studies add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating that prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with alterations in NMDA receptor subunit levels (Table 1). While many of the previously published studies identified changes in tissue collected from the early postnatal period, we found that NMDA receptor subunit levels were altered in adult animals. The persistence of these alterations into adulthood indicates that modifications of glutamatergic neurotransmission could underlie the learning and memory deficits that are observed in adult animals that were exposed prenatally to ethanol.

Tissue Homogenate Studies Revealed That NR2A Subunit Levels Are Reduced in the Hippocampal Formation of Prenatal Ethanol-Exposed Mice

The fact that we observed reduced NR2A, but not NR1 or NR2B, protein levels in homogenates prepared from hippocampi isolated from FAE mice compared to Sacc mice in the presence of unaltered mRNA expression of the subunits indicates that the reduction in NR2A protein may be the result of differential post-transcriptional processing of the protein in the FAE mouse hippocampus. This observation is consistent with other studies showing that, in some cases, NMDA receptor subunit mRNA levels do not correlate with protein levels (Awobuluyi et al., 2003; Gazzaley et al., 1996). While the exact mechanism for how NR2A expression is decreased in FAE hippocampal homogenates was not formally addressed in our studies, reduced translation and/or increased degradation of the NR2A protein in FAE hippocampus should be evaluated in future studies.

In contrast to our findings of a lack of an effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on NMDA receptor subunit mRNA levels, Toso and colleagues (2005) found a significant decrease in NR2B and an increase in NR2AmRNA levels in whole brain tissue from adult mice prenatally exposed to alcohol. We attribute this apparent discrepancy to our studies being conducted using hippocampal tissue, whereas Toso and colleagues used whole brain homogenates, which lack regional specificity. Our results do, however, agree with previous studies by Naassila and Daoust (2002) and Hughes and colleagues (2001), who found that NR2A and NR2B mRNA levels in the hippocampus and cortex of rat pups were not affected by prenatal alcohol exposure.

Synaptosomal Membrane (LP1) Analyses Revealed That FAE NR1 Levels Were Significantly Increased and NR2A and NR2B Levels Were Unaffected by Prenatal Alcohol Exposure

Goebel-Goody and colleagues (2009) reported that, although synaptic receptors predominate in the LP1 preparations, both synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors are present in this fraction. Thus, our observation of an increase in NR1 protein in the LP1 fraction of FAE animals compared to Sacc samples does not identify whether the apparent increase is localized in the synaptic, extrasynaptic, or both, compartment( s). Upregulation of NR1 subunits has previously been associated with chronic ethanol exposure (reviewed in Ron, 2004). Therefore, increases in NR1 levels could be a compensatory response to prolonged NMDA receptor inhibition in utero that persist into adulthood in the absence of postpartum alcohol exposure. Recent studies suggest that increases in NMDA receptors may be a consequence of ethanol’s actions on gene expression (Mameli et al., 2005; Qiang et al., 2005; Sanderson et al., 2009). However, it is unlikely that the latter argument underlies the observed increase in NR1 subunits associated with the LP1 fraction in FAE mice since we found no alterations in NR1 subunit mRNA expression. Thus, prenatal alcohol-induced alterations in NR1 subunit localization in the LP1 fraction appear to occur via a post-transcriptional mechanism.

Previous studies have shown that hippocampal levels of NR1 in young rats are unaffected by prenatal alcohol exposure (Hughes et al., 1998; Nixon et al., 2004). Apparent discrepancies between the results of our studies and these previous studies may be attributed to the use of different animal models (mouse and rat), different methods of prenatal alcohol exposure, the age of the animals used, or differences in the tissue preparations in which receptor expression was assessed. This last point may be particularly relevant, as our data were collected using LP1 fractions, rather than a cruder P2 synaptosomal preparation, as was employed by Hughes and colleagues (1998) and Nixon and colleagues (2004). Whereas less pure synaptosomal preparations may contain trapped intracellular pools of NMDA receptor subunits, the preparation of the LP1 fraction includes a hypotonic lysis procedure, which should result in the release of these receptors. It has been suggested that the intracellular pool of NR1 subunits is relatively large (Al-Hallaq et al., 2007; Huh and Wenthold, 1999). While intracellular pools of NMDA receptor subunits were not directly addressed in our experiments, the identification of no difference in Sacc and FAE NR1 levels in unfractionated hippocampal homogenate samples combined with the LP1 fraction results is consistent with a reduction in the intracellular reserve of NR1 subunits in the FAE mouse hippocampal formation. This conclusion is based on the assumption that the level of receptor subunits measured in tissue homogenates includes all subcellular pools of receptor and that receptors not present in LP1 membrane preparations are intracellular. Future studies could assess this possibility using chymotrypsin or cross-linking techniques in hippocampal slices, as performed in Grosshans and colleagues (2002).

The observed lack of an effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on synaptosomal membrane levels of NR2A subunit protein in our studies agrees with a study by Hughes and colleagues (1998), who reported no effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on NR2A levels measured in a crude synaptosomal fraction isolated from animals at postnatal days 7 and 21, but differ from the results of Nixon and colleagues (2004), who found that combined prenatal and postnatal alcohol exposure is associated with increased NR2A levels in hippocampal crude synaptosomal fraction prepared from postnatal day 10 animals. Although our data indicate that prenatal ethanol exposure may be associated with an alteration in synaptosomal NR2A levels, this trend was not significant. Preliminary experiments and power analysis suggested that 80% power would be achieved with our sample size. In fact, power analysis of the NR1 data revealed that we had over 80% power; however, in the NR2A data, there was a higher than expected amount of variance which led to decreased power in these studies. Thus, our studies concluded that the trend in the NR2A data is not significant, but future studies will aim to decrease variance and increase sample size in order to further evaluate his trend. Our observation that the reduction in total homogenate NR2A protein levels are accompanied by no change in synaptosomal membrane levels of the subunit protein may indicate that, in our mouse model, intracellular levels of NR2A are reduced by prenatal ethanol exposure.

Our results indicating no change in NR2B expression in LP1 fractions from adult animals coincide with previous findings by Hughes and colleagues (1998), who reported that, although NR2B levels in the hippocampus of postnatal day 1 animals were reduced, there was no difference in older animals (postnatal day 7 or 21). Alternatively, Dettmer and colleagues found a significant decrease in NR2B expression in the cerebral cortex of adult guinea pigs whose mothers had a relatively high maternal blood ethanol concentration of 71 mM (~327 mg/dl) throughout gestation (Dettmer et al., 2003). However, we attribute these apparent discrepancies to differences in blood ethanol concentrations, tissue used and species of animals used in our respective studies.

Isolated Anti-PSD-95 Immune Complexes Have Decreased NR2B Association in FAE Samples and No Change in NR2A or NR1 Levels

Our anti-PSD-95 immunoprecipitation studies revealed a significant decrease in PSD-95-associated NR2B levels in the FAE hippocampus. If we assume that the association of NR2B subunits with PSD-95 is representative of postsynaptic membrane populations of NMDA receptors, as was done by Honse and colleagues (2003), then our results indicate that synaptic NR2B expression is decreased in FAE hippocampus. Taken together with our data showing no difference in LP1 (synaptosomal membrane) fraction NR2B levels, this suggests that the decrease in synaptic NR2B is associated with lateral movement of the receptor to extrasynaptic sites, rather than internalization of the receptor. Recently, disruption of the PSD-95/NR2B complex was shown to cause a redistribution of NR2B-containing receptors from synaptic to extrasynaptic sites (Gardoni et al., 2009) supporting our proposal that decreased PSD-95-associated NR2B levels observed in FAE animals are indicative of a shift from synaptic to extrasynaptic locations. Additionally, an FAE-associated increase in NR2B extrasynaptically is consistent with our proposal of an increase in extrasynaptic NR1 subunits in FAE mice (see below). Decreased synaptic NR2B expression may help to explain some of the findings previously associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (see below).

Our data demonstrating that prenatal ethanol exposure was associated with reduced PSD-95-associated NR2B, but not NR2A, subunit levels differ from the findings of Honse and colleagues (2003), who reported that, in P21 rat cortices, there is a significant decrease in NR2A, but not NR2B, that co-immunoprecipitates with PSD-95 in prenatal ethanolt-reated animals. Hughes and colleagues (2001) also reported no difference in PSD-95-associated NR2B subunits in postnatal day-1 rat cortices. Potential reasons for the discrepancy between our respective data could be due to Hughes and colleagues and Honse and colleagues using young rat cortical tissue compared to our studies in adult mouse hippocampal tissue. Additionally, there are also differences in our models of prenatal alcohol exposure—e.g., we use a voluntary drinking paradigm, rather than liquid diet.

Immunoprecipitation experiments also revealed that PSD-95 associated NR1 levels were not altered by prenatal alcohol exposure. Once again, if we assume that these studies are representative of postsynaptic membrane receptors, this would suggest that NR1 levels are not altered in the synapse and that the observed increase in NR1 levels found in the LP1 experiments may be attributed to increased NR1 expression in extrasynaptic locations.

Decreased Synaptic NR2B Levels Associated With Prenatal Alcohol Exposure Are Consistent With Various Previously Reported Effects of Prenatal Ethanol Exposure

Our results indicating that synaptic NR2B expression may be decreased in prenatal alcohol-exposed animals combined with the fact that NR2B-containing receptors carry more Ca2+ per unit of current (Yashiro and Philpot, 2008) indicate that prenatal alcohol may affect NMDA-dependent Ca2+ influx. This proposal is consistent with studies that have shown that prenatal alcohol significantly reduces NMDA-mediated Ca2+ influx into dissociated neurons isolated from brain regions including the hippocampus (Lee et al., 1994; Spuhler-Phillips et al., 1997).

Activation of NR2B-containing receptors leads to extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation (Chen et al., 2007; Krapivinsky et al., 2003). Our lab previously reported that FAE animals have deficits in NMDA receptor-mediated ERK activation in the hippocampal formation (Samudio-Ruiz et al., 2009). Decreased synaptic NR2B subunits in FAE samples may play a role in this deficit. In support of this claim, a recent study showed that disruption of the PSD-95/NR2B complex decreases CREB (a known target of ERK) phosphorylation (Gardoni et al., 2009).

NR2B-containing receptors in the hippocampal formation CA1 region and prefrontal cortex have been implicated in synaptic potentiation and contextual fear memory (Gardoni et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2005). Furthermore, it has been shown that transgenic mice overexpressing the NR2B subunit show enhanced NMDA receptor channel activity, enhanced LTP and enhanced learning and memory (Tang et al., 1999), while decreased PSD-95/NR2B association has been shown to impair LTP (Gardoni et al., 2009). Thus, decreased PSD-95-associated NR2B in our mouse model of prenatal alcohol exposure may, in part, be responsible for the learning deficits that we have observed in adult offspring (Allan et al., 2003).

Limitations of the Present Studies

There are clear confines to our studies which limit the conclusions that can be made based on the data. Due to the insoluble nature of NMDA receptors and PSD-95 and the fact that DOC treatment solubilized relatively low percentages of the total proteins, we recognize that our immunoprecipitation experiments may be evaluating a subpopulation of PSD-95-associated NMDA receptors. Additionally, synaptic NMDA receptors associate with MAGUK family scaffolding proteins other than PSD-95, including synapse associated protein of 97 kDa (SAP-97), SAP-102, and PSD-93, which bind NMDA receptor NR2A and NR2B subunits (Lau and Zukin, 2007; Sans et al., 2000). Although the PSD-95-associated receptor complex is the predominant receptor pool present in the synapse (Cousins et al., 2008), we can not exclude the possibility that prenatal ethanol has caused additional changes in synaptic NMDA receptor subunit levels via effects on the association of NMDA receptor with other MAGUK family members. A third consideration is that our studies do not address whether there are changes in the expression levels of NR1 splice variants, which have been shown to be affected in rat models of prenatal alcohol exposure (Honse et al., 2003; Naassila and Daoust, 2002). Finally, our studies were carried out using whole hippocampus and do not distinguish between CA1, CA3, or dentate gyrus fields of the hippocampus, which display regional differences in NMDA receptor subunit expression, as shown in studies by Coultrap and colleagues (2005).

CONCLUSIONS

Our studies are to our knowledge the first to evaluate the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on NMDA receptor subunit levels in adult hippocampal formation synaptosomal membrane and isolated anti-PSD-95 immune-complexes. We found that prenatal alcohol exposure does, in fact, cause alterations in NMDA receptor subunit composition that exist in adult animals long after the insult of alcohol is gone. We show evidence here that FAE adult mice display decreased total NR2A, increased synaptic membrane NR1 and decreased PSD-95-associated NR2B levels in the hippocampal formation. Our results are consistent with a model in which prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with a redistribution of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors from a synaptic to an extrasynaptic location, which may be an underlying factor in the learning and memory deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Chynoweth and David Leonard for technical assistance. We also thank Nora Perrone-Bizzozero and C. Fernando Valenzuela for thoughtful discussion throughout the course of these studies and the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH-NIAAA award #1F31AA017001-01 (S. L. Samudio-Ruiz), NIH-NIAAA award #1T32AA014127 (C. F. Valenzuela), NIH-NIAAA award # 1P20AA017068 (D. D. Savage), and Dedicated Health Research Funds from the University of New Mexico School of Medicine (A. M. Allan, K. K. Caldwell).

References

- Abdollah S, Brien JF. Effect of chronic maternal ethanol administration on glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate binding sites in the hippocampus of the near-term fetal guinea pig. Alcohol. 1995;12:377–382. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)00021-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abulrob A, Tauskela JS, Mealing G, Brunette E, Faid K, Stanimirovic D. Protection by cholesterol-extracting cyclodextrins: a role for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor redistribution. J Neurochem. 2005;92:1477–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hallaq RA, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Wenthold RJ. NMDA di-Heteromeric receptor populations and associated proteins in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8334–8343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2155-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hallaq RA, Jarabek BR, Fu Z, Vicini S, Wolfe BB, Yasuda RP. Association of NR3A with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR1 and NR2 subunits. Mol Pharm. 2002;62:1119–1127. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan AM, Chynoweth J, Tyler LA, Caldwell KK. A mouse model of prenatal ethanol exposure using a voluntary drinking paradigm. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:2009–2016. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000100940.95053.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awobuluyi M, Vazhappilly R, Sucher NJ. Translational activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR1 mRNA in PC12 cells. Neurosignals. 2003;12:283–291. doi: 10.1159/000075310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier E, Pierrefiche O, Vaudry D, Vaudry H, Daoust M, Naassila M. Long-term alterations in vulnerability to addiction to drugs of abuse and in brain gene expression after early life ethanol exposure. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1199–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger FP, Davidson MS, Bedi KS, Wilce PA. Neonatal ethanol exposure reduces AMPA but not NMDA receptor levels in the rat neocortex. Dev Brain Res. 2002;136:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RF, Hannigan JH. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the hippocampus: spatial behavior, electrophysiology and neuroanatomy. Hippocampus. 2000;10:94–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<94::AID-HIPO11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blahos J, II, Wenthold RJ. Relationship between N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR1 splice variants and NR2 subunits. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15669–15674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell KK, Sheema S, Paz RD, Samudio-Ruiz SL, Laughlin MH, Spence NE, Roehlk MJ, Alcon SN, Allan AM. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder-associated depression: evidence for reductions in the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in a mouse model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler LJ, Sutton G, Dorairaj NR, Norwood D. N-methyl D-aspartate receptor-mediated bidirectional control of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity in cortical neuronal cultures. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2627–2636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Chang H, Huang L, Lai M, Yang C, Wan T, Yang S. Alterations in long-term seizure susceptibility and the complex of PSD-95 with NMDA receptor from animals previously exposed to perinatal hypoxia. Epilepsia. 2006;47:288–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, He S, Hu X-L, Yu J, Zhou Y, Zheng J, Zang S, Zhang C, Duan W-H, Xiong Z-Q. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in activity dependent brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene regulation and limbic epileptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:542–552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3607-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ET, Olivera DS, Meyer DA, Ferreira VM, Soto EE, Frausto S, Savage DD, Browning MD, Valenzuela CF. Fetal alcohol exposure alters neurosteroid modulation of hippocampal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000b;275:38268–38274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ET, Savage DD, Valenzuela CF. A review of the effects of prenatal or early postnatal ethanol exposure on brain ligand-gated ion channels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000a;24:706–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultrap SJ, Nixon KM, Alvestad RM, Valenzuela CF, Browning MD. Differential expression of NMDA receptor subunits and splice variants among CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Mol Brain Res. 2005;135:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins SL, Papdakis M, Rutter AS, Stephenson FA. Differential interaction of NMDA receptor subtypes with post-synaptic density-95 family of membrane associated guanylate kinase proteins. J Neurochem. 2008;104:903–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer TS, Barnes A, Iqbal U, Bailey CDC, Reynolds JN, Brien JF, Valenzuela CF. Chronic prenatal ethanol exposure alters ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit protein levels in the adult guinea pig cerebral cortex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:677–681. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000060521.32215.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Granados JL, Spuhler-Phillips K, Lilliquist MW, Amsel A, Leslie SW. Effects of prenatal and early postnatal ethanol exposure on [3H]MK-801 binding in rat cortex and hippocampus. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:874–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunah AW, Standaert DG. Dopamine D1 receptor-dependent trafficking of striatal NMDA glutamate receptors to the postsynaptic membrane. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5546–5558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyashiki T, Fujisawa K, Fujita A, Maduale P, Uchino S, Mishina M, Bito H, Narumiya S. Citron, a Rho-target, interacts with PSD-95/SAP-90 at glutamatergic synapses in the Thalamus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:109–118. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardoni F, Mauceri D, Malinverno M, Polli F, Costa C, Tozzi A, Siliquini S, Picconi B, Cattabeni F, Calabresi P, Di Luca M. Decreased NR2B subunit synaptic levels cause impaired long-term potentiation but not long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2009;29:669–677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3921-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley AH, Weiland NG, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Differential regulation of NMDAR1 mRNA and protein by estradiol in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6830–6838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06830.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel-Goody SM, Davies KD, Alvestad-Linger RM, Freund RK, Browning MD. Phospho-regulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors inadulthippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1446–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans DR, Clayton DA, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. LTP leads to rapid surface expression of NMDA but not AMPA receptors in adult rat CA1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nn779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE. 2B synaptic or extrasynaptic determines signalling from the NMDA receptor. J Physiol. 2006;572:614–615. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AZ, Pettit DL. Extrasynaptic and synaptic NMDA receptors form stable and uniform pools in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 2007;584:509–519. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honse Y, Nixon KM, Browning MD, Leslie SW. Cell surface expression of NR1 splice variants and NR2 subunits is modified by prenatal ethanol exposure. Neuroscience. 2003;122:689–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PD, Kim YN, Randall PK, Leslie SW. Effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on the developmental profile of the NMDA receptor subunits in rat forebrain and hippocampus. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1255–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PD, Wilson WR, Leslie SW. Effect of gestational ethanol exposure on the NMDA receptor complex in rat forebrain: from gene transcription to cell surface. Dev Brain Res. 2001;129:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh KH, Wenthold RJ. Turnover analysis of glutamate receptor identifies a rapidly degraded pool of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit, NR1, in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:151–157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner WB, Schiebler W, Greengard P, De Camilli P. Synapsin I (protein I), a nerve terminal-specific phosphoprotein. III. Its association with synaptic vesicles studied in highly purified synaptic vesicle preparation. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1374–1388. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.5.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal U, Brien JF, Kapoor A, Matthews SG, Reynolds JN. Chronic prenatal ethanol exposure increases glucocorticoid-induced glutamate release in the hippocampus of the near-term foetal guinea pig. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:826–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov A, Pellegrino C, Rama S, Dumalska I, Salyha Y, Ben-Ari Y, Medina I. Opposing role of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in regulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) activity in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2006;572:789–798. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Manasian Y, Ivanov A, Tyzio R, Pellegrino C, Ben-Ari Y, Clapham DE, Medina I. The NMDA receptor is coupled to the ERK pathway by a direct interaction between NR2B and RasGRF1. Neuron. 2003;40:775–784. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CG, Zukin RS. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-H, Spuhler-Phillips K, Randall PK, Leslie SW. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on NMDA-mediated calcium entry into dissociated neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1291–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim IA, Hall DD, Hell JW. Selectivity and promiscuity of the first and second PDZ domains of PSD-95 and synapse associated protein 102. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21697–21711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mameli M, Zamudio PA, Carta M, Valenzuela CF. Developmentally regulated actions of alcohol on hippocampal glutamatergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8027–8036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2434-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland PJ, Luong NT, Woodward JJ, Chandler LJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase is autonomous from the dominant extrasynaptic NMDA receptor extracellular signal-regulated kinase shutoff pathway. Neuroscience. 2008;151:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naassila M, Daoust M. Effect of prenatal and postnatal ethanol exposure on the developmental profile of mRNAs encoding NMDA receptor subunits in rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2002;80:850–860. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K, Hughes PD, Amsel A, Leslie SW. NMDA receptor subunit expression after combined prenatal and postnatal exposure to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:105–112. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000106311.88523.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Neyton J. NMDA receptor subunits: function and pharmacology. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang M, Rani CS, Ticku MK. Neuron-restrictive silencer factor regulates the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2B subunit gene in basal and ethanol-induced gene expression in fetal cortical neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:2115–2125. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rema V, Ebner FF. Effect of enriched environment rearing on impairments in cortical excitability and plasticity after prenatal alcohol exposure. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10993–11006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D. Signaling cascades regulating NMDA receptor sensitivity to ethanol. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:325–336. doi: 10.1177/1073858404263516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudio-Ruiz SL, Allan AM, Valenzuela CF, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Caldwell KK. Prenatal ethanol exposure persistently impairs NMDA receptor dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the mouse dentate gyrus. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1311–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson JL, Partridge LD, Valenzuela CF. Modulation of GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission by ethanol in the developing neocortex: an in vitro test of the excessive inhibition hypothesis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans N, Petralia RS, Wang Y, Blahos J, II, Hell JW, Wenthold RJ. A developmental change in NMDA receptor-associated proteins at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1260–1271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01260.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Montano CY, Otero MA, Paxton LL. Prenatal ethanol exposure decreases hippocampal NMDA-sensitive [3H]-glutamate binding site density in 45-day-old rats. Alcohol. 1991;8:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(91)90806-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spuhler-Phillips K, Lee YH, Hughes P, Randoll L, Leslie SW. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on brain region NMDA-mediated increase in intracellular calcium and the NMDAR1 subunit in forebrain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi N, Logan R, Teves L, Wallace MC, Gurd JW. Altered interaction between PSD-95 and the NMDA receptor following transient global ischemia. J Neurochem. 2000;74:169–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401:63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toso L, Poggi SH, Abebe D, Roberson R, Dunlap V, Park J, Spong CY. N-methyl-D-aspartate subunit expression during mouse development altered by in utero alcohol exposure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1534–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel A, Fritschy JM, Mohler H, Benke D. NMDA receptor heterogeneity during postnatal development of the rat brain differential expression of the NR2A, NR2B, and NR2C subunit proteins. J Neurochem. 1997;68:469–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H, Liu X, Matos MF, Chan SF, Perez-Otano I, Boysen M, Cui J, Nakanishi N, Trimmer JS, Jones EG, Lipton SA, Sucher NJ. Temporal and regional expression of NMDA receptor subunit NR3A in the mammalian brain. J Comp Neurol. 2002;450:303–317. doi: 10.1002/cne.10314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K, Philpot B. Regulation of NMDA receptor subunit expression and its implications for LTD, LTP and metaplasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1081–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wu L, Gong B, Ren M, Li B, Zhuo M. Induction- and conditioning-protocol dependent involvement of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in synaptic potentiation and contextual fear memory in the hippocampal CA1 region of rats. Mol Brain. 2008;1:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao MG, Toyoda H, Lee YS, Wu LJ, Ko SW, Zhang XH, Jia Y, Shum F, Xu H, Li BM, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Roles of NMDA NR2B subtype receptor in prefrontal long-term potentiation and contextual fear memory. Neuron. 2005;47:859–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]