Abstract

Torpor during hibernation defines the nadir of mammalian metabolism where whole animal rates of metabolism are decreased to as low as 2% of basal metabolic rate. This capacity to decrease profoundly the metabolic demand of organs and tissues has the potential to translate into novel therapies for the treatment of ischemia associated with stroke, cardiac arrest or trauma where delivery of oxygen and nutrients fails to meet demand. If metabolic demand could be arrested in a regulated way, cell and tissue injury could be attenuated. Metabolic suppression achieved during hibernation is regulated, in part, by the central nervous system through indirect and possibly direct means. In this study, we review recent evidence for mechanisms of central nervous system control of torpor in hibernating rodents including evidence of a permissive, hibernation protein complex, a role for A1 adenosine receptors, mu opiate receptors, glutamate and thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Central sites for regulation of torpor include the hippocampus, hypothalamus and nuclei of the autonomic nervous system. In addition, we discuss evidence that hibernation phenotypes can be translated to non-hibernating species by H2S and 3-iodothyronamine with the caveat that the hypothermia, bradycardia, and metabolic suppression induced by these compounds may or may not be identical to mechanisms employed in true hibernation.

Keywords: metabolic arrest, metabolic suppression, suspended animation

Hibernating animals display a variety of adaptations that protect the central nervous system from metabolic challenges and trauma that are injurious in non-hibernating species. These adaptations include profound decreases in brain and body temperature (Tb) and immune function, enhanced antioxidant defenses, and metabolic suppression (Drew et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2001; Ross et al. 2006). Metabolic suppression, a regulated and reversible reduction in cellular and tissue need for oxygen and nutrients, matches metabolic demand with supply and is one of the most novel yet least well-understood neuroprotective aspects of hibernation. Knowledge of mechanisms used by hibernating animals to decrease metabolic demand to as low as 2% of basal metabolic rate or 0.01 mL O2/g/h (Geiser 1988; Buck and Barnes 2000) has the potential to translate into therapies for a host of conditions where failed delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain and other energy-demanding organs leads to disability or death. In this study, we: (i) provide background information on hibernation; (ii) review recent evidence for mechanisms of central nervous system control of torpor in hibernating mammals; and (iii) discuss the potential to translate the hibernation phenotype to non-hibernating species towards a goal of pharmacologically inducing metabolic suppression or suspended animation for therapeutic purposes in humans.

Recent reviews have assimilated information on cellular and molecular aspects of hibernation (Boyer and Barnes 1999; Carey et al. 2003; Heldmaier et al. 2004). Here we focus on central nervous system (CNS) regulation of metabolic suppression in torpid hibernators. This focus acknowledges the caveat that adaptations necessary to endure hypometabolism, hypothermia, and extreme fluctuations in blood flow also occur at the cell and tissue level (Hillion et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2007; Mamady and Storey 2006) or may occur constitutively without any CNS influence (Harris et al. 2004; Dave et al. 2006).

What is hibernation?

Hibernation is a behavioral, physiological, and molecular adaptation exhibited by diverse mammalian species to withstand protracted periods or seasons of insufficient or unpredictable food availability. Hibernation is characterized by intervals of profound decreases in whole-body metabolic rate and Tb which last from days to several weeks known as prolonged torpor. These torpor bouts are interrupted by brief (approximately 1 day), spontaneous arousals that occur at regular intervals. During interbout arousals animals spontaneously return to high, euthermic Tb of 35–37°C that fall within the normal range of diurnal Tb observed during the active season (Geiser and Ruf 1995). Based on changes in Tb and whole-body metabolic rate (MR), hibernation can be subdivided into separate stages of entry, when MR and Tb decrease, steady-state torpor when Tb and MR remain minimal and are defined by the gradient between Tb and ambient temperature, arousal episodes, called interbout arousal, when MR and Tb increase and short periods of interbout euthermy (Boyer and Barnes 1999; Carey et al. 2003). Torpor during hibernation is not a state of energy exigency or exhaustion; rather, it is highly regulated, adaptive, and reversible as animals can spontaneously rewarm to euthermia within hours in the absence of applied exogenous heat (Carey et al. 2003). Through these highly regulated processes, torpor defines the lower limit of mammalian metabolism and is associated with an altered state of consciousness distinct from wakefullness, sleep, or coma.

What is torpor?

In this review, the term torpor will be used to specify the period in hibernation that is characterized by suppressed Tb and MR. The term torpor is used rather than hibernation as hibernation refers to a process that encompasses several months of prolonged torpor, interrupted by, but including arousal episodes. Torpor during hibernation is distinct from daily torpor displayed by a variety of small mammals (Geiser 2004). Moreover, torpor is operationally distinguished from hypothermia when metabolic suppression precedes a fall in core Tb (Lyman 1958).

Functional neuronal activity persists in hibernation

Studies of EEG activity in rodents show that torpor is entered during non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep. As brain temperature decreases the predominant EEG power spectra slow to lower frequencies (Deboer 1998), and REM sleep is not described at temperatures below 21–25°C (Krilowicz et al. 1988; Strijkstra et al. 1999). During deep torpor, cortical EEG is isoelectric, although at Tb of 14–36°C, EEG patterns are similar to those of NREM sleep (Krilowicz et al. 1988). Thus, it has been proposed that torpor constitutes a neurological extension of NREM sleep, but that the low Tb of torpor makes torpor distinct from any sleep state (Berger 1984; Berger and Phillips 1988; Heller 1988; Kilduff et al. 1993).

Hibernating animals retain coordinated postures and the ability to arouse in response to external stimulation as well as periodically (Heller 1979). However, the role of action potential-dependent neuronal activity in this coordinated behavior remains unclear. Low Tb characteristic of deep torpor inhibit the generation and propagation of action potentials, reduce the efficacy of synaptic transmission and will generally inhibit brain activity. The duration of action potentials increases as Tb decreases from 27 to 10°C (Krilowicz et al. 1989). Although species-specific temperature compensation has not been fully characterized some neurons of hibernating species generate and conduct impulses and initiate synaptic transmission at the low Tb associated with deep torpor, albeit with reduced capacities (Milsom et al. 1993; Harris and Milsom 1995). In contrast, at temperatures below 16.7°C spontaneous action potentials are not observed in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of acute brain slices from hibernating or euthermic ground squirrels. Loss of spontaneous action potentials in both of these states is explained in part by the thermal sensitivity of the sodium channel (Miller et al. 1994). Finally, while long-term potentiation can be established at high temperatures in hippocampal slices from hibernating animals, the phenomenon is lost at temperatures below 22°C (Krelstein et al. 1990; Spangenberger et al. 1995; Bronson et al. 2006).

Facultative versus obligate hibernators

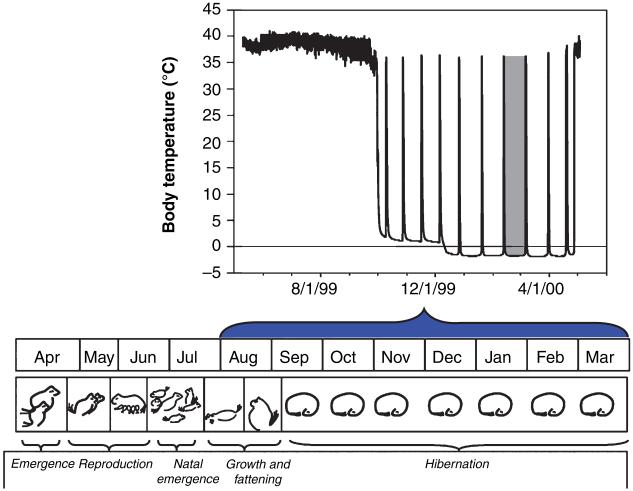

Spontaneity and timing of hibernation in mammals can be facultative or obligate. Facultative hibernators, such as Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus), are induced to hibernate by short photoperiods followed by gonadal regression; frequency of torpor is increased by food restriction and low ambient temperatures (Hoffman et al. 1968; Geiser 2004). Obligate hibernators, such as ground squirrels, marmots, and chipmunks, will spontaneously hibernate in long or short photoperiods and in the presence of food. Hibernation in these species follow an endogenous, circannual rhythm that, under natural conditions, is entrained to a 12-month period by seasonal fluctuations in day length (Pengelley et al. 1976; Davis and Swade 1983; Hiebert et al. 2000) (Fig. 1). Similar neural mechanisms may be involved in control of torpor in both groups of hibernators.

Fig. 1.

Seasonal cycle of hibernation, reproduction and fattening in Arctic ground squirrels (AGS). AGS are obligate hibernators with a pronounced circannual cycle. The gray bar in the upper panel highlights a single torpor bout within repeated torpor bouts that occur throughout the hibernation season spanning from September to April. Our model proposes that during the hibernation season a photic-entrained signaling molecule sensitizes the adenosinergic system or alters responsiveness of downstream components of sleep promoting pathways.

Active versus passive (temperature-dependent) processes in metabolic suppression

Reduced rates of metabolism during torpor are thought to be attained through synergistic effects of both passive (temperature dependent) and active (temperature-independent) processes that serve to decrease oxygen demand (Heldmaier et al. 2004). The degree of reliance on either active or passive suppression of metabolic processes during entry and maintenance of torpor appears to be influenced by the size of the animal; active processes play a greater role in relatively large (BM≥1000 g) and very small hibernators (<100 g) whereas in intermediate sized hibernators, passive, or Tb associated processes appear to be the most important determinant of metabolic rate (Geiser 2004).

Large hibernators actively suppress metabolism during both the entry and maintenance phases of torpor. During entry, whole animal oxygen consumption, heart rate and respiratory rate drop precipitously prior to a more gradual decline in core Tb (Lyman 1958). Active inhibition is evidenced by metabolic rate reductions that precede Tb change, and changes in metabolism exceed those expected by changes in temperature alone. For example, active inhibition is suggested by greater than the anticipated range of 2–3-fold decreases in oxygen consumption for every 10°C drop in temperature (Buck and Barnes 2000; Geiser 2004). In addition, rates of oxygen consumption of larger hibernators during steady-state torpor do not correlate with change in Tb over an intermediate range of ambient temperatures above 0°C (Heller et al. 1977; Buck and Barnes 2000; Heldmaier et al. 2004). For example, arctic ground squirrels during steady-state torpor maintain constant and minimal rates of oxygen consumption despite as much as a 16°C difference in Tb (Buck and Barnes 2000). Thus, for large hibernators it appears that active suppression of metabolism occurs for both entry to the torpid phase and for maintaining low torpid metabolic rates especially at relatively high Tb’s.

Circannual cycles in obligate hibernators

Proximate mechanisms that regulate entry and arousal from torpor in obligate (seasonal) hibernators are superimposed upon regulated circannual changes in appetite, body mass, reproduction, immune responsiveness, antioxidant defenses and other physiological processes (Drew et al. 2001; Carey et al. 2003) (Fig. 1). Indeed dynamic, seasonally dependent aspects of the “hibernation phenotype” makes identifying regulatory mechanisms of prolonged torpor a moving target and adds considerable complexity to the design and interpretation of hibernation research. Here we define the term “hibernation phenotype” as a collection of circannually controlled phenotypes identified by (i) preparation for hibernation including weight gain and increases in adiposity with a preference for specific polyunsaturated fatty acids; (ii) onset of torpor at the beginning of the hibernation season; (iii) phases of rewarming, euthermia, and recooling that make up the spontaneous and regular arousal episodes that interrupt torpor throughout the hibernation season; (iv) gradual lengthening and then shortening of torpor bout length as the season progresses; and (v) activation of gonadal maturation and ultimate arousal at the end of the hibernation season (Barnes et al. 1988; Frank and Storey 1995; Carey et al. 2003). This definition of “hibernation phenotype” is based primarily on the study of sciurids, including ground squirrels, chipmunks, marmots and woodchucks, that are by far the best-studied group with regard to physiology of seasonal hibernation.

Control groups in the study of torpor

Investigations of the genetic, molecular, and neurobiological control of hibernation usually compare torpid animals with those of animals sampled while at euthermic Tb either after an arousal or during what is considered their non-hibernating or active season. Torpid animals, however, also usually differ from active animals by being fasted and exposed to cold. Comparing animals in torpor and animals during interbout arousal may be confounded by recent torpor in the aroused group and direct effects of Tb differences that are not related to the regulation of torpor. Comparison between summer active animals and torpid animals in winter may be confounded by differences related to season that may or may not be related to hibernation or to the state of torpor, for example reproduction, molt, or growth (Wang 1989). As circannual rhythms free-run in environmental conditions of unchanging photoperiod and temperature, animals kept in captivity for more than several months will become out of phase with each other which complicates selecting equivalent, non-hibernating controls (Davis 1976). Animals kept at 16–21°C may show daily or multi-day torpor that is undetected unless continuous monitoring of Tb is performed. These difficulties in defining a valid control group for the study of torpor emphasizes the need for well designed, manipulative studies that address cause and effect relationships among parameters that change during hibernation and torpor.

Identification of molecules that change with the hibernation season and influence torpor is a first step towards understanding the backdrop on which torpor is regulated. Here we review evidence of CNS regulation of hibernation in both facultative and obligate hibernators including several species within each group. We extend contributions of prior reviews of neural control of torpor in hibernating animals (Heller 1979; Kilduff et al. 1993; Pakhotin et al. 1993; Nurnberger 1995; Milsom et al. 1999) by focusing on recent manipulations shown to influence the frequency, onset or duration of torpor in a physiological or pharmacological manner and expand previously proposed theories of CNS regulation of torpor that incorporates these new findings.

Hibernation protein complex

Recent evidence suggests that, in chipmunks, seasonal regulation of a group of four hibernation-specific proteins termed HP plays an essential, permissive role in torpor. Three of the four proteins (HP20, 25 and 27) form a complex called HP20c. HP20c associates in blood with a larger (HP55) protein to form HPc (Kondo and Kondo 1992). According to a circannual rhythm that correlates with the hibernation season, some amount of HPc in blood is transported into the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) in conjunction with dissociation of HP55 from the complex leading to an increase in HP20c in brain. At the same time, HP production and blood levels are down-regulated. Although the function of HP20c is unknown, it is hypothesized to play a role in seasonal preparation and cellular adaptation necessary for hibernation. Animals that do not hibernate fail to experience decreases in HP in plasma and increases in HP20c in CSF during the hibernation season. Moreover, anti-HP20c antibodies administered intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) induce arousal (Kondo et al. 2006).

Kondo et al. (2006) suggests that HP produced in the liver and secreted into blood carries hormonal signals to the brain. These signals then provide an environment in which proximate mechanisms act to induce torpor. A decrease in HP in blood and increase in CSF is triggered prior to the onset of hibernation and is sustained throughout the hibernation season despite periodic arousals. Thus, the protein complex does not induce torpor per se. Rather, HP provides a permissive hormonal signal that is essential for hibernation and is regulated by an endogenous circannual rhythm (Kondo et al. 2006). This, as well as other circannual rhythms essential for torpor, imposes a seasonal constraint on the study of CNS control of torpor.

Brain regions involved in the regulation of torpor

Inter-relationships among hibernation, reproduction, and energy homeostasis suggest a role for the hypothalamus in altered thermoregulation, neuroendocrine control and timing of torpor. Evidence also suggests that the hippocampus and its target, the medial septum-diagonal band complex, are involved in hibernation circuitry (Heller 1979; Belousov et al. 1990; Pakhotin et al. 1993). Finally, the autonomic nervous system is likely critical for entrance into torpor, and many processes during torpor continue to be regulated by the autonomic nervous system (Harris and Milsom 1995; Milsom et al. 1999). Although potential neural circuits have been proposed (Heller 1979) and warrant modification as new data are generated, in general, the literature is lacking in results from site and receptor-specific manipulations or tract tracing studies. However, because models can help to shape testable hypotheses, concepts of neurochemical circuits, temperature effects, and cellular metabolism have been integrated with prior models of neural control of torpor (Heller 1979; Beckman 1982) and a revised model is discussed below.

Theories of hypothalamic control of torpor

Altered thermoregulation

Superimposed on a circannual hibernation rhythm are proximate mechanisms that regulate entry and reversal of torpor that include altered thermoregulation. Body temperature declines during entrance into torpor because energy-consuming heat production is diminished. Cooling the preoptic anterior hypothalamus (POAH) initiates shivering and other heat-generating and energy-consuming responses when brain temperature falls below a set-point temperature (Heller et al. 1977). As animals enter torpor, progressively lower Tb’s are required to initiate thermogenesis, and this decrease in the temperature ‘set-point’ allows for a fall in Tb (Heller et al. 1977). By analogy, turning down a home’s thermostat shuts off the furnace and decreases fuel usage while ambient temperature cools at a rate dependent upon thermal gradients, insulation and other factors. By extension, although the thermostatic set-point is lower, the pilot light remains lit and is analogous to the many processes that continue to operate to maintain organismal homeostasis albeit at a lower Tb. Warm- and cold-sensitive neurons exist within the hypothalamus (Hori et al. 1988), and thermosensitive neurons within the POAH may modulate behavioral state via inhibition or disfacilitation of arousal systems (Krilowicz et al. 1994). Warming hypocretin neurons proximate to POAH by over expression of uncoupling protein (UCP2) decreases core Tb and extends life span (Conti et al. 2006). Nonetheless, little is known about the neurochemical control of thermoregulation within the POAH, hampering methods to induce alternations pharmacologically in thermoregulation and metabolic suppression as seen in animals entering torpor.

Adenosine

The nucleoside adenosine is an inhibitory neuromodulator. Extracellular adenosine originates via extracellular conversion of adenine nucleosides or from intracellular pools by way of equilibrative transporters (Dunwiddie and Masino 2001). Adenosine acts as a retaliatory neuromodulator in part because as high energy phosphates decline, intracellular adenosine accumulates and is shuttled out of the cell via facilitated diffusion (Dunwiddie and Masino 2001; Alanko et al. 2006). CO2 inhibits cortical excitability via an interaction between adenosine, extracellular pH, ATP metabolizing enzymes, and receptors for ATP (Dulla et al. 2005).

Role of adenosine in thermoregulation associated with hibernation

Similarities exist between the change in thermoregulation observed with the onset of torpor and that occurring during the metabolic response induced when rodents are exposed to low oxygen environments (Bullard et al. 1960; Barros et al. 2001; Tattersall and Milsom 2003). Although neither hypoxia nor hypercapnia are sufficient to induce multiday torpor (Bullard et al. 1960; Heldmaier et al. 2004), understanding neurochemical regulation of the hypoxic metabolic response may shed light on altered thermoregulation and metabolism occurring with hibernation. Adenosine is an inhibitory neuromodulator that, when applied exogenously, acts on the central nervous system to produce hypothermia (Miller and Hsu 1992). When administered i.c.v., the non-selective adenosine antagonist, aminophylline, attenuates hypoxia-induced hypothermia suggesting that central adenosine plays a role in the thermoregulatory response to hypoxia (Barros and Branco 2000). Moreover, injection of the A1 antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine directly into the anteroventral preoptic area attenuates hypoxia-induced hypothermia (Barros et al. 2006).

Adenosine may likewise play a role in altered thermoregulation during entrance into torpor. The adenosine-A1 receptor agonist, cyclohexyladenosine, administered into the lateral ventricle of hamsters induces a decrease in Tb comparable to that seen in this species during hibernation (Shiomi and Tamura 2000). Moreover, i.c.v. administration of 8-cyclopenthyltheophylline, an A1 antagonist, but not 3, 7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine, an A2 antagonist, induces arousal from torpor, but only when administered early in a hibernation bout. Interestingly, animals made hypothermic by i.c.v. administration of cyclohexyladenosine lacked ability to spontaneously arouse, suggesting that early torpor is regulated differently from late torpor and arousal (Tamura et al. 2005). Taken together, these data suggest that adenosine plays a role in altered thermoregulation during entrance and early maintenance of torpor.

Role of adenosine in sleep associated with hibernation

Alternatively, adenosine may regulate entrance into torpor via neuromodulation of sleep drive. The basal forebrain is well known to be sensitive to changes in adenosine efflux where adenosine is thought to be a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness via A1 receptor inhibition of cholinergic and non-cholinergic neurons (Porkka-Heiskanen et al. 1997; Arrigoni et al. 2006). Slow wave sleep precedes entry into torpor and immediately follows arousal, supporting the hypothesis that torpor may be an extension of sleep (Walker et al. 1977; Kilduff et al. 1993; Pastukhov 1997; Strijkstra and Daan 1997). Moreover, during slow wave sleep, the hypothalamic temperature threshold for initiating metabolic heat production is decreased similar to altered thermoregulation and metabolism seen in torpor (Glotzbach and Heller 1976). Neuroregulatory control of sleep may therefore hold important clues to CNS regulation of torpor (Heller and Ruby 2004). Neurons that release hypocretin (also known as orexin) modulate sleep, arousal, and energy homeostasis (Li et al. 2002). These hypocretin neurons, located in the perifornical nucleus and the dorsal and lateral hypothalamus, ramify widely throughout the brain and innervate a large number of loci, including those already recognized as playing roles in attention and arousal (Peyron et al. 1998). Recent evidence shows that, in addition to effects in the basal forebrain, adenosine exerts a sleep-promoting effect in the lateral hypothalamus via inhibition of hypocretin neurons (Liu and Gao 2007). Additionally, the preoptic hypothalamus plays a role in sleep through projections to sleep promoting regions and reciprocal connections with the basal forebrain (Mohns et al. 2006) In the POAH, adenosine disinhibits and promotes expression of sleep-related neuronal activity and thermosensitive neurons of the POAH exert control of sleep-waking state, in part, via modulation of arousal- and sleep-regulating cell types within the basal forebrain (Alam et al. 1995).

Suprachiasmatic nucleus and circannual timing of hibernation

Substantial evidence points to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) as an integral, component of hibernation circuitry. Relative utilization of glucose by the SCN remains higher than that of most other brain structures during deep torpor (Kilduff et al. 1982) and expression of c-fos mRNA increases in SCN during arousal (Bitting et al. 1994; O’Hara et al. 1999). SCN lesions have been shown to alter circannual timing of hibernation and uncouple circannual rhythms in body mass and reproduction in ground squirrels. SCN-lesioned ground squirrels continue to hibernate in spring and summer and gain weight (in contrast to the typical weight loss) over the course of the hibernation season (Ruby et al. 1996, 1998). Circadian rhythms in Tb persist during torpor in some species of ground squirrels and hamsters (Grahn et al. 1994; Ruby et al. 2002) and these rhythms are disrupted by SCN lesions. Thus, while a photic/circadian influence on the SCN may modulate torpor and may be necessary to signal final arousal in the spring, modified circadian mechanisms and/or non-photic-related pathways may also play a role.

Melatonin is one signaling molecule with receptors in the SCN that may play a role in regulation of torpor. While melatonin is synthesized primarily in the pineal gland, arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase (AA-NAT), the rate-limiting enzyme in melatonin biosynthesis, is found in retina and other brain regions including the SCN (Coon et al. 1995). AA-NAT mRNA is increased in SCN of hibernating ground squirrels (Yu et al. 2002). This same group found evidence for up-regulation of the melatonin receptor Mel1a during torpor (McCarron et al. 2001) suggesting that intra-SCN melatonin may play a role in hibernation.

Considerable advances have been made in our understanding of the glutamatergic pathway from the retina to the SCN and glutamatergic modulation of the circadian clock (Mintz et al. 1999). Less well studied are the non-photic inputs to the SCN. Recent neuroanatomical mapping of SCN inputs show how hormones and visceral information can influence the SCN directly and via polysynaptic pathways. Many of these stimuli and pathways may influence the SCN and torpor circuitry via effects of peptide hormones acting on the SCN through circumventricular organs, glucocorticoids acting on SCN via the temporal lobe and hippocampus, and visceral information associated with hunger or changes in blood gases acting on the SCN via the autonomic nervous system and nucleus of the solitary tract (Krout et al. 2002). Recent evidence further indicates that sleep states alter the activity of the SCN through yet unknown mechanisms (Deboer 1998). Finally, neurons projecting from the SCN give rise to pre-sympathetic and pre-parasympathetic pathways capable of modulating autonomic nervous system function (Buijs et al. 2003). Thus, the SCN is in a position to integrate information regarding vigilance, as well as photic, endocrine and autonomic stimuli and to communicate these integrated signals to the autonomic motor system and other components of the torpor circuit to influence metabolic and thermoregulatory processes that control energy expenditure during hibernation.

Theories of autonomic nervous system control of torpor

The autonomic nervous system is instrumental in directly and indirectly regulating metabolic rate (Shibao et al. 2007). Opposing parasympathetic and sympathetic signals determine the autonomic output of the brain to the body and are a primary mechanism of homeostatic control. The status of the autonomic nervous system is demonstrated by patterns of heart rate, with sympathetic influences acting to accelerate heart rate while parasympathetic influences decrease this rate. Investigations of heart rate and heart rate responses to pharmacological manipulations during hibernation have long been used as the basis for speculation regarding the status of autonomic nervous system influence during hibernation (Lyman 1982).

During entrance into or arousal from torpor, changes in heart rate, as well as rates of oxygen consumption, respiration and cerebral blood flow all precede changes in core Tb (Lyman 1982; Geiser 1988; Toien et al. 2001; Osborne and Hashimoto 2003). Opposing parasympathetic and sympathetic forces change in balance over states, such as the sleep-wake cycle, and during transitions into and out of torpor. The patterns of these changes support the model that parasympathetic tone coordinates entrance into states of hypometabolism while an increase in sympathetic tone initiates arousal (Twente and Twente 1978; Harris and Milsom 1995; Milsom et al. 1999). The physiological regulation of entrance to and emergence from hypometabolic states may, therefore, lie within the control of autonomic outflow.

Outside of these transition periods, the role of the autonomic nervous system in regulating stable heterothermic states is controversial. Two polarized views have been established that provide conflicting theoretical roles for autonomic regulation of stable hibernation. One theory suggests that the parasympathetic nervous system actively suppresses the sympathetic nervous system and subsequent arousal during deep hibernation (Twente and Twente 1978). An opposing theory that has gained more widespread acceptance is that parasympathetic modulation disappears during prolonged torpor (Lyman 1982). Parasympathetic nervous system activity is suggested to wane as temperature falls because it is thought that low Tb’s normally associated with states, such as deep torpor are incompatible with parasympathetic nervous system function (Lyman and O’Brien 1963; Lyman 1982; Harris and Milsom 1995). Both theories have drawn evidence from studies of heart rate during torpor, and this has been the topic of a detailed review (Milsom et al. 1999).

Reduced preparations derived from hibernating animals demonstrate that despite the low Tb’s associated with torpor the autonomic nervous system remains functional. Autonomic nerves conduct action potentials, albeit requiring greater magnitudes of stimulation over euthermia as would be expected at low Tb’s (O’Shea and Evans 1985; Milsom et al. 1993). Nerve stimulation initiates transmitter release and the heart retains sensitivity to cholinergics, catecholamines and adrenergic agonists (Twente and Twente 1978; Lyman 1982; O’Shea 1987; Milsom et al. 1993). As such, although altered to an expected degree by low Tb, the autonomic nervous system retains its ability to influence homeostasis during torpor. What remains unclear is to what degree these autonomic influences modulate stable torpor.

Initially, a continued role for parasympathetic influence was suggested from observations that atropine increased the heart rate and abolished cardiac arrhythmias in a number of species during deep torpor (Twente and Twente 1978). Elevated heart rates following vagotomy provides further evidence for continued parasympathetic influence during deep torpor. Several hibernating species exhibit intermittent and periodic patterns of breathing separated by prolonged apnea during torpor. Spontaneous periods of breathing are associated with sinus arrhythmia. The magnitude of this ventilatory tachycardia decreases with Tb during torpor (Harris and Milsom 1995; Milsom et al. 1999; Zimmer and Milsom 2001). Vagotomy performed on torpid animals eliminates the ventilatory tachycardia by elevating heart rates during the periods of apnea to match those during ventilation (Harris and Milsom 1995). Recently, similar patterns of ventilatory tachycardia were documented during hypometabolic states of torpor in fat-tailed Dunnarts and Western pygmy possums (Zosky 2002; Zosky and Larcombe 2003). In these studies, parasympathetic antagonism eliminated heart rate variability and elevated heart rate in a manner similar to vagotomy in ground squirrels. These results suggest that vagal/parasympathetic influences are retained during torpor. Observations such as these lend support to the view that parasympathetic influences could indeed be active during torpor. It remains to be seen if parasympathetic influences dominate sympathetic influences and contribute to the active inhibition of arousal.

Other neurotransmitters, neuromodulators and hormones thought to play a role in hibernation

Role of glutamatergic transmission in torpor

Systemic administration of MK-801, a non-competitive NMDA antagonist that acts as an open-channel blocker, induces arousal in golden mantled ground squirrels (Harris and Milsom 2000). The high dose (5.0 mg/kg) of MK-801, found to be effective, may be necessary to overcome severely limited absorption and distribution in torpid hibernators. These results suggest that a glutamatergic process may actively maintain torpor and/or prevent arousal. Further studies are warranted to clarify the pharmacological specificity of this MK-801-induced response.

Glutamate immunoreactivity decreases while GABA immunoreactivity increases in SCN during torpor (Nürnberger et al. 2000). Further work is required to interpret the functional significance of altered immunoreactivity of neurotransmitters during torpor because an increase in immunoreactivity may reflect decreased transmitter release. Extracellular concentrations of glutamate in the striatum, a structure thought to reflect global changes rather than region-specific effects, remains constant throughout torpor and euthermy (Zhou et al. 2002). Equally surprising, extracellular levels of GABA in striatum decrease during torpor when inhibitory neurotransmitter tone would be expected to increase (Osborne et al. 1999). Failure for global changes in excitatory and inhibitory tone to explain altered CNS metabolism in hibernation suggests that metabolic suppression is regulated via higher level processes. If MK-801 induces arousal via inhibition of NMDA receptors as discussed above, the effects are likely site-specific as glutamatergic activation of an inhibitory process is necessary to explain how an excitatory neurotransmitter enhances overall inhibition. Indeed, glutamatergic terminals synapse on inhibitory GABAergic interneurons throughout the brain including the hippocampus (Henze et al. 2000). Glutamate is an enticing candidate as a regulatory molecule during torpor because via transanimation to a-ketoglutarate, it is tightly linked to TCA cycle activity and can be released via mechanisms that do not require action potentials (Moran et al. 2005; Santos et al. 2006).

Role of other signaling molecules in torpor

Mu opiate receptor activation is necessary for maintenance of late torpor (Tamura et al. 2005). These results extend previous findings in golden mantled ground squirrels showing that nalaxone, a non-selective opiate antagonist, reduces torpor bout duration (Beckman and Llados-Eckman 1985). Moreover, the selective influence on late torpor suggests mu opiate receptor activation plays a role in maintenance of prolonged torpor (Tamura et al. 2005). While mu opioid receptors are found throughout the brain including the hippocampus, hypothalamus and brainstem, the most dose sensitive mu opioid effect is slowing respiratory rhythm through actions on brainstem respiratory control centers (Lalley 2006). Thus, mu opioid-mediated enhancement of parasympathetic influence on respiratory rhythm, potentially at the level of the nucleus of the solitary tract (Browning et al. 2006), may facilitate coupling of metabolic demand and respiratory drive in deep torpor.

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulates metabolism and induces hyperthermia through release of thyroid stimulating hormone from the pituitary as well as through direct sympathetic nervous system activation (Griffiths 1985). TRH, administered directly into the lateral ventricle, induces arousal from hibernation in Syrian hamsters during both entrance and maintenance phases of torpor. This is in contrast to A1 and mu opiate antagonists that induce arousal only in early and late phases of torpor, respectively (Tamura et al. 2005). The action of TRH is due, in part, to direct stimulation of sympathetic innervation of intrascapular brown adipose tissue and non-shivering thermogenesis as well as via affects of TRH within the dorsomedia, ventromedial and anterior hypothalamus, and the POAH (Shintani et al. 2005). Ability to induce arousal independent of torpor phase is consistent with the hypothesis that inhibition of sympathetic output is necessary for successful hibernation. The role of TRH in naturally induced arousal is unclear; however, evidence suggests that TRH may accumulate in some brain regions during a torpor bout (Stanton et al. 1982) and TRH microinjected into the area postrema produces excitatory effects on respiration (Mutolo et al. 1999).

Histamine, synthesized by tuberomammillary neurons in the posterior hypothalamus that project throughout the CNS is known to play a role in wakefulness. Paradoxically, histamine injected into the hippocampus prolongs torpor bout duration (Sallmen et al. 2003a). While a role for H3 autoreceptors has been proposed, further study of H3 agonists and antagonists is required. The hippocampus is regarded as an essential brain structure in neural control of hibernation in part because it is the last structure to lose EEG power during entrance into hibernation and the first to regain EEG power during arousal from hibernation (Heller 1979; Beckman 1982). In the hippocampus, histamine immunoreactivity and tele-methyl histamine levels increase during hibernation and hibernation associated changes are observed in expression of histamine receptors (Sallmen et al. 1999, 2003b,c). Changes in immunoreactivity, tele-methyl histamine levels and receptor expression are difficult to interpret, however, especially in brains of hibernating animals where protein synthesis is actively suppressed and activity of many enzymes decrease due to temperature-dependent effects.

Pharmacologic manipulation of torpor, as always, requires the use of appropriate vehicle controls and interpretation is significantly enhanced when receptor specificity can be demonstrated with selective agonists and/or antagonists as demonstrated by Tamura et al. (2005). Focus on pharmacological specificity of response helps to eliminate spurious results that are more common in studies of hibernation than most other behaviors because extraneous physical stimuli can artificially induce arousal, and the intensity of stimulation needed to induce arousal varies with both season and duration of torpor (Twente and Twente 1968). Indeed, hibernating ground squirrels require less stimulation to induce arousal early and late in the hibernation season compared with mid-season (Twente and Twente 1968; Harris and Milsom 1994) and are more likely to arouse in response to physical stimulation in the last half of each hibernation bout (Twente and Twente 1968).

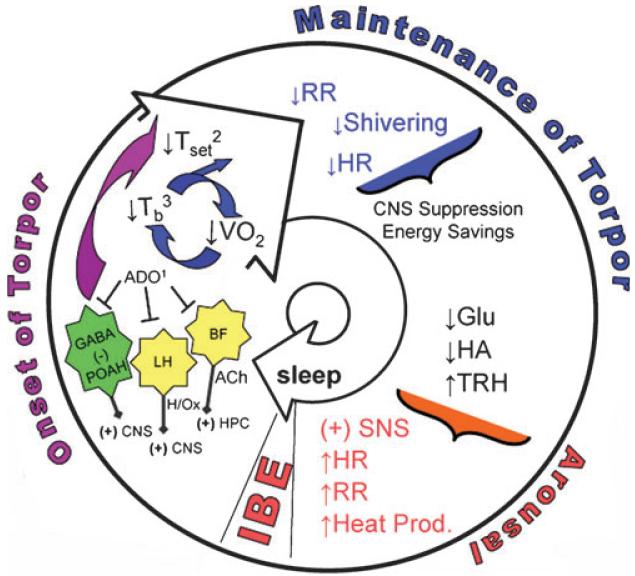

Integration with previous models

Much of the data reviewed here remains consistent with neural models of torpor proposed more than 25 years ago (Heller 1979; Beckman 1982). Here we offer more specific neurochemical and anatomical details for the model (Fig. 2) with the caveat that rigorous, site- and receptor-specific pharmacological manipulation of torpor is needed to test hypotheses generated by this model. Previous models identified the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) as a primary site regulating torpor and arousal (Heller 1979; Beckman 1982). Anatomically, the ARAS includes two populations of cholinergic neurons located in the pontine reticular formation and in the basal forebrain where the latter includes, but is not limited to, magnocellular neurons in the medial septum and the diagonal band (McKinney and Jacksonville 2005). ARAS activation may be suppressed during entrance into torpor via influence of adenosine within the basal forebrain which projects reciprocally to the POAH as well as to the same wake-promoting nuclei as the POAH (Arrigoni et al. 2006; Mohns et al. 2006). Adenosine may also disinhibit and promote expression of sleep-related neuronal activity in the POAH (Strecker et al. 2000). Adenosine-mediated inhibition of hypocretin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus may also contribute to sleep drive (Liu and Gao 2007) and subsequent onset of torpor.

Fig. 2.

Hypothesized mechanisms regulating onset, maintenance and arousal from an individual torpor bout. This process repeats itself in a regular manner throughout the hibernation season as shown in Fig. 1. Adenosine (1) is hypothesized to initiate the onset of torpor through sleep promoting mechanisms and through a decrease in Tset within the POAH. The decrease in Tset (2) results in an immediate decrease in metabolism via decreased heat production. HR and RR then decrease due to activation of PSNS and decreased energy demand. Direct influence on ANS may also contribute to metabolic suppression. Subsequent cooling (3) decreases neuronal activity. Cooling-induced decrease in activity of medial septohippocampal neurons decreases theta rhythm until EEG becomes isoelectric. Cooling also produces additional metabolic suppression through temperature-dependant (Q10) reductions in metabolic processes. Torpor is maintained via temperature dependent suppression of biochemical processes, -Opioid receptor activation and possibly via melatonin-mediated inhibition of respiration, and glu stimulation of PSNS or glu and HA stimulation of inhibitory pathways influencing arousal. Arousal is hypothesized to result from depletion of a signaling molecule, such as Glu or HA and activation of the SNS via TRH. ADO (adenosine); BF (basal forebrain); LH (lateral hypothalamus); POAH (preoptic anterior hypothalamus); ACh (acetylcholine); HPC (hippocampus); H/Ox (hypocretin/Orexin); Tset (threshold temperature of hypothalamus necessary to induce thermogenesis); PSNS (parasympathetic nervous system), ANS (autonomic nervous system); VO2 (whole animal oxygen consumption); HR (heart rate); RR (respiratory rate); Tb (core body temperature); Q10 (ratio of reaction rates for a 10°C change in tissue temperature); SCN (suprachiasmatic nucleus); Glu (glutamate); HA (histamine); TRH (thyrotropin-releasing hormone); SNS (sympathetic nervous system); IBE (interbout euthermy).

Inhibition of POAH efferent neurons and output from other wake-promoting nuclei are further proposed to induce decreases in heart rate, respiratory rate, and shivering via activation of the parasympathetic nervous system in response to altered temperature ‘set-point’ (Tset) upon entrance into torpor (Heller et al. 1977) (Florant et al. 1978). Subsequent cooling is then proposed to suppress neuronal activity and theta rhythm within septohippocampal neurons and throughout the brain, leading to enhanced CNS suppression and energy savings (Strijkstra et al. 1999; Bronson et al. 2006). Suppression of respiratory rhythm may be maintained via mu opioid receptor activation within the nucleus of the solitary tract (Browning et al. 2006) or upstream within the hypothalamus (Zhou et al. 2006), or through a melatonin-mediated mechanism within the SCN.

If, indeed, adenosine and/or inhibition of hypocretin neurons initiate the onset of torpor through increased sleep drive or attenuation of arousal, what pushes heterothermic animals beyond sleep and into multiday torpor? Here the model proposes that a photic-entrained signaling molecule, such as the hibernation protein complex (Kondo et al. 2006), sensitizes the adenosinergic system or alters responsiveness of downstream components of the proposed pathways.

Mechanisms regulating arousal are distinct from mechanisms regulating onset of torpor based on observations that some pharmacological manipulations are effective in early torpor (e.g., adenosine antagonists) and others are effective in late torpor (mu opioid antagonists) (Tamura et al. 2005). Our model proposes that regularly timed sensitization to arousal involves depletion of a critical pool of neurotransmitter, such as glutamate. Glutamate is maintained, in part, through an anaplerotic pathway via pyruvate carboxylase (Oz et al. 2004) such that decreased TCA flux as is seen in hibernation would be expected to decrease glutamate synthesis. Loss of non-synaptic glutamatergic tone, potentially at the level of the SCN or tuberomammillary nucleus may reverse activation of an inhibitory influence on the sympathetic nervous system. Furthermore, activation of the sympathetic nervous system via TRH, loss of histamine or other means leads to arousal via stimulation of thermogenesis, heart rate, and respiration.

Translation to other species

Hibernation is widespread phylogenetically and is expressed in the three subclasses of mammals and one family of birds (Geiser 2004). This distribution argues that hibernation is an ancestral trait and that genes required for hibernation are common to all mammals (Srere et al. 1992). Aspects of the hibernation phenotype resemble characteristics common to all mammalian neonates, including a tolerance of hypothermia and hypometabolism. The capacity to endure or induce hibernation-like hypometabolic states may therefore represent a trait common to all mammals (Harris et al. 2004) and supports the notion that it may be possible to induce hibernation-like torpor in mammalian species, including humans, that do not normally express the hibernation phenotype. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) suppresses oxygen consumption in mice in a manner characteristic of torpor where metabolic suppression precedes a fall in Tb (Blackstone et al. 2005). In brain tissue, endogenously produced H2S reaches micromolar concentrations where it modulates NMDA receptors and dilates cerebral arterioles via activation of KATP channels [reviewed by (Leffler et al. 2006)]. Thus, H2S could induce “suspended animation” in mice via effects on physiological sites of H2S action at concentrations of 80 ppm (estimated to produce tissue concentrations of 6–8 μmol/L). Alternatively, the H2S-induced torpor-like hypothermia may mimic a hypoxic-metabolic response as H2S is a potent inhibitor of brain cytochrome c oxidase activity with an IC50 of 0.13 μmol/L (Wallace and Starkov 2000). If H2S reversibly suppresses metabolism because it is a chemical inhibitor of cellular respiration, it is unclear why salts of cyanide or azide do not reversibly suppresses metabolism as well. Like cyanide, H2S is a non-competitive, heme binding inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase (Wallace and Starkov 2000). Details with regard to metabolism, decline of Tb, and arousal, may not be identical for H2S, hypoxia and hibernation-induced torpor because different physiological and cellular mechanisms likely contribute to processes involved with entrance, maintenance and emergence from torpor. Some differences are apparent when H2S-induced hypothermia is compared to daily torpor entry and arousal in mice (Hudson and Scott 1979).

Hypoxia, food deprivation, and chemical inhibitors of metabolic pathways suppress metabolism and Tb. How hypothermia induced by these metabolic poisons relates to natural torpor-inducing signals remains unclear. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) and mercaptoacetate, inhibitors of glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation, respectively have been used in recent investigations of metabolic fuel deprivation in regulation of torpor (Dark and Miller 1997; Stamper et al. 1999; Westman and Geiser 2004). Results of the investigations are mixed and may illustrate a situation where torpor-inducing cues may differ between facultative and obligate hibernators. In the eastern pygmy-possum (Cercartetus nanus), where hibernation is not strongly seasonal in contrast to, e.g., ground squirrels where it is very seasonal, administration of 2DG induces a torpor-like state, but the magnitude of change in Tb and metabolism is less than that in spontaneous torpor. Mercaptoacetate induces a torpor-like state in some C. nanus that is more consistent with naturally induced torpor (Stamper et al. 1999; Westman and Geiser 2004). Similarly, in Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus), a facultative hibernator, lipoprivation, but not glucoprivation induces a torpor-like state (Schneider et al. 1993). In contrast, administration of 2DG or mercaptoacetate to an obligate hibernator, such as the golden-mantled ground squirrel, fails to induce torpor (Dark and Miller 1998) and caloric restriction in this species delays the onset of hibernation (Pulawa and Florant 2000). Thus, while circannual cycles of hibernation may have evolved in obligate hibernators as a result of food shortage, fuel deprivation is not sufficient to induce torpor in these animals. In contrast, fuel deprivation appears to play a greater role in inducing torpor in facultative hibernators, however, there is no definitive evidence that pharmacologically induced deprivation with 2DG or mercaptoacetate can unilaterally induce or maintain torpor either individually or in combination. With regard to pharmacological initiators of torpor-like states in non-heterothermic species, it appears that more studies are needed to clearly delineate the exact role of 2DG and mercaptoacetate.

3-Iodothyronamine (T1AM) is another pharmacological compound known to induce profound hypothermia and bradycardia in rodents (Scanlan et al. 2004). T1AM is a naturally occurring derivative of thyroid hormone that is a potent agonist of the G-protein coupled receptor TAR1 and has physiological effects that are opposite to thyroid hormone (Scanlan et al. 2004). Further research is necessary to investigate the role of T1AM in hibernation.

In summary, although CNS regulation of hibernation is as yet, little understood, integrating data from both facultative and obligate hibernators supports a model where a circannually regulated hibernating protein complex, activated upon transport into the CSF, permits metabolic flexibility regulated via neural pathways. Sympathetic activation of thermogenic tissues and cardiorespiratory centers is suppressed, and parasympathetic inhibition of metabolically active processes is enhanced, potentially via an adenosine-mediated decrease in wakefulness or thermogenic drive. The subsequent decrease in CNS activation and metabolic demand facilitates cooling which, in turn, facilitates additional metabolic suppression via down-regulation of temperature-dependent processes including neuronal activity. This highly regulated and coordinated state that defines the nadir of mammalian metabolism is overturned by periodic activation of a mu opiate-regulated process. Further research is required to define the neural networks and transmitter systems through which glutamate and hippocampal histamine influence hibernation. Better understanding of neurochemical aspects of CNS regulation of hibernation may lead to pharmacological means to induce metabolic suppression in non-hibernating species and guide development of novel therapies for patients suffering stroke, cardiac arrest, shock and other conditions where energy supply fails to meet demand.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank B.P. Warlick, T. Lee and C. Brundage for helpful discussions and literature searches, L. Hollen for assistance with figures and T.S. Kilduff for critical review of a previous version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH-NS41069, funded in part by NINDS, NIMH, NCRR and NCMHD, by US Army Med. Res. and Materiel Command 05178001, by US Army Research Office #W911NF-05–1-0280 and by a post-doctoral fellowship to SLC from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Abbreviations used

- ARAS

ascending reticular activating system

- POAH

preoptic anterior hypothalamus

- REM

rapid-eye-movement

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- TRH

thyrotropin-releasing hormone

References

- Alam N, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Local preoptic/anterior hypothalamic warming alters spontaneous and evoked neuronal activity in the magno-cellular basal forebrain. Brain Res. 1995;696:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00884-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanko L, Porkka-Heiskanen T, Soinila S. Localization of equilibrative nucleoside transporters in the rat brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2006;31:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigoni E, Chamberlin NL, Saper CB, McCarley RW. Adenosine inhibits basal forebrain cholinergic and noncholinergic neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2006;140:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes BM, Kretzmann M, Zucker I, Licht P. Plasma androgen and gonadotropin levels during hibernation and testicular maturation in golden-mantled ground squirrels. Biol. Reprod. 1988;38:616–622. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod38.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RC, Branco LG. Role of central adenosine in the respiratory and thermoregulatory responses to hypoxia. Neuroreport. 2000;11:193–197. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RC, Zimmer ME, Branco LG, Milsom WK. Hypoxic metabolic response of the golden-mantled ground squirrel. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:603–612. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros RC, Branco LG, Carnio EC. Respiratory and body temperature modulation by adenosine A1 receptors in the anteroventral preoptic region during normoxia and hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2006;153:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman AL, editor. Properties of the CNS during the state of hibernation. Spectrum; New York: 1982. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman AL, Llados-Eckman C. Antagonism of brain opioid peptide action reduces hibernation bout duration. Brain Res. 1985;328:201–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belousov AB, Vinogradova OS, Pakhotin PI. Paradoxical state-dependent excitability of the medial septal neurons in brain slices of ground squirrel Citellus undulatus. Neuroscience. 1990;38:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RJ. Slow wave sleep, shallow torpor and hibernation: homologous states of diminished metabolism and body temperature. Biol. Psychol. 1984;19:305–326. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(84)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RJ, Phillips NH. Comparative aspects of energy metabolism, body temperature and sleep. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 1988;574:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitting L, Sutin EL, Watson FL, Leard LE, O’Hara BF, Heller HC, Kilduff TS. C-fos mRNA increases in the ground squirrel suprachiasmatic nucleus during arousal from hibernation. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;165:117–121. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science. 2005;308:518. doi: 10.1126/science.1108581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer BB, Barnes BM. Molecular and metabolic aspects of hibernation. Bioscience. 1999;49:713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Bronson NW, Piro JB, Hamilton JS, Horowitz JM, Horwitz BA. Temperature modifies potentiation but not depotentiation in bidirectional hippocampal plasticity of Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Brain Res. 2006;1098:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN, Zheng Z, Gettys TW, Travagli RA. Vagal afferent control of opioidergic effects in rat brainstem circuits. J. Physiol. 2006;575:761–776. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck CL, Barnes BM. Effects of ambient temperature on metabolic rate, respiratory quotient, and torpor in an arctic hibernator. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;279:R255–R262. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM, la Fleur SE, Wortel J, Van Heyningen C, Zuiddam L, Mettenleiter TC, Kalsbeek A, Nagai K, Niijima A. The suprachiasmatic nucleus balances sympathetic and parasympathetic output to peripheral organs through separate preautonomic neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;464:36–48. doi: 10.1002/cne.10765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard RW, David G, Nichols CT, editors. The mechanisms of hypoxic tolerance in hibernating and non-hibernating mammals, in Mammalian Hibernation. Vol. 24. Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College; Cambridge, MA: 1960. pp. 321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Carey HV, Andrews MT, Martin SL. Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:1153–1181. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti B, Sanchez-Alavez M, Winsky-Sommerer R, et al. Transgenic mice with a reduced core body temperature have an increased life span. Science. 2006;314:825–828. doi: 10.1126/science.1132191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon SL, Roseboom PH, Baler R, Weller JL, Namboodiri MA, Koonin EV, Klein DC. Pineal serotonin N-acetyl-transferase: expression cloning and molecular analysis. Science. 1995;270:1681–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dark J, Miller DR. Metabolic fuel privation in hibernating and awake ground squirrels. Physiol. Behav. 1997;63:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dark J, Miller DR. Metabolic fuel privation in hibernating and awake ground squirrels. Physiol. Behav. 1998;63:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave KR, Prado R, Raval AP, Drew KL, Perez-Pinzon MA. The Arctic ground squirrel brain is resistant to injury from cardiac arrest during euthermia. Stroke. 2006;37:1261–1265. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217409.60731.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DE. Hibernation and circannual rhythms of food consumption in marmots and ground squirrels. Q. Rev. Biol. 1976;51:477–514. doi: 10.1086/409594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DE, Swade RH. Circannual rhythm of torpor and molt in the ground squirrel, Spermophilus beecheyi. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 1983;76:183–187. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(83)90312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboer T. Brain temperature dependent changes in the electroencephalogram power spectrum of humans and animals. J. Sleep Res. 1998;7:254–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew KL, Rice ME, Kuhn TB, Smith MA. Neuroprotective adaptations in hibernation: therapeutic implications for ischemia-reperfusion, traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:563–573. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00628-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulla CG, Dobelis P, Pearson T, Frenguelli BG, Staley KJ, Masino SA. Adenosine and ATP link PCO2 to cortical excitability via pH. Neuron. 2005;48:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florant GL, Turner BM, Heller HC. Temperature regulation during wakefulness, sleep, and hibernation in marmots. Am. J. Physiol. 1978;235:R82–R88. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1978.235.1.R82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CL, Storey KB. The optimal depot fat composition for hibernation by golden-mantled ground squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis) J. Comp. Physiol. [B] 1995;164:536–542. doi: 10.1007/BF00261394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser F. Reduction of metabolism during hibernation and daily torpor in mammals and birds: temperature effect or physiological inhibition? J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1988;158:25–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00692726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser F. Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:239–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser F, Ruf T. Hibernation versus daily torpor in mammals and birds: physiological variables and classification of torpor patterns. Physiol. Zool. 1995;68:935–966. [Google Scholar]

- Glotzbach SF, Heller HC. Central nervous regulation of body temperature during sleep. Science. 1976;194:537–539. doi: 10.1126/science.973138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn DA, Miller JD, Houng VS, Heller HC. Persistence of circadian rhythmicity in hibernating ground squirrels. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:R1251–R1258. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths EC. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone: endocrine and central effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1985;10:225–235. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(85)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Milsom W. The ventilatory response to hypercapnia in hibernating golden-mantled ground squirrels. Physiol. Zool. 1994;67:739–755. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Milsom WK. Parasympathetic influence on heart rate in euthermic and hibernating ground squirrels. J. Exp. Biol. 1995;198:931–937. doi: 10.1242/jeb.198.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, Milsom WK. Is hibernation facilitated by an inhibition of arousal? In: Heldmaier G, Klingenspor M, editors. Life in the Cold. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2000. pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Olson L, Milsom W. The origin of mammalian heterothermy: a case for perpetual youth. In: Barnes B, Carey H, editors. Twelfth International Hibernation Symposium. Life in the Cold: Evolution, Mechanisms, Adaptation, and Application. Vol. 27. Institute of Arctic Biology; Fairbanks, Alaska: 2004. pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Heldmaier G, Ortmann S, Elvert R. Natural hypometabolism during hibernation and daily torpor in mammals. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2004;141:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller HC. Hibernation: neural aspects. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1979;41:305–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.41.030179.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller HC. Sleep and hypometabolism. Can. J. Zool. 1988;66:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Heller HC, Ruby NF. Sleep and circadian rhythms in mammalian torpor. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:275–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller HC, Colliver GW, Beard J. Thermoregulation during entrance into hibernation. Pflügers Arch. 1977;369:55–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00580810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze DA, Urban NN, Barrionuevo G. The multifarious hippocampal mossy fiber pathway: a review. Neuroscience. 2000;98:407–427. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert SM, Thomas EM, Lee TM, Pelz KM, Yellon SM, Zucker I. Photic entrainment of circannual rhythms in golden-mantled ground squirrels: role of the pineal gland. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2000;15:126–134. doi: 10.1177/074873040001500207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillion JA, Li Y, Maric D, Takanohashi A, Klimanis D, Barker JL, Hallenbeck JM. Involvement of Akt in preconditioning-induced tolerance to ischemia in PC12 cells. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1323–1331. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RA, Robinson PF, Magalhaes H, editors. The Golden Hamster; its biology and use in medical research. The Iowa State University Press; Ames Iowa, USA: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Yamasaki M, Asami T, Koga H, Kiyohara T. Responses of anterior hypothalamic-preoptic thermosensitive neurons to thyrotropin releasing hormone and cyclo(His-Pro) Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JW, Scott IM. Daily torpor in the laboratory mouse, Mus musculus var. albino. Physiol. Zool. 1979;52:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff TS, Sharp FR, Heller HC. [14C]2-deoxyglucose uptake in ground squirrel brain during hibernation. J. Neurosci. 1982;2:143–157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-02-00143.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff TS, Krilowicz B, Milsom WK, Trachsel L, Wang LC. Sleep and mammalian hibernation: homologous adaptations and homologous processes? Sleep. 1993;16:372–386. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N, Kondo J. Identification of novel blood proteins specific for mammalian hibernation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:473–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N, Sekijima T, Kondo J, Takamatsu N, Tohya K, Ohtsu T. Circannual control of hibernation by HP complex in the brain. Cell. 2006;125:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krelstein MS, Thomas MP, Horowitz JM. Thermal effects on long-term potentiation in the hamster hippocampus. Brain Res. 1990;520:115–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91696-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krilowicz BL, Glotzbach SF, Heller HC. Neuronal activity during sleep and complete bouts of hibernation. Am. J. Physiol. 1988;255:R1008–R1019. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.6.R1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krilowicz BL, Edgar DM, Heller HC. Action potential duration increases as body temperature decreases during hibernation. Brain Res. 1989;498:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krilowicz BL, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Regulation of posterior lateral hypothalamic arousal related neuronal discharge by preoptic anterior hypothalamic warming. Brain Res. 1994;668:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krout KE, Kawano J, Mettenleiter TC, Loewy AD. CNS inputs to the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the rat. Neuroscience. 2002;110:73–92. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalley PM. Opiate slowing of feline respiratory rhythm and effects on putative medullary phase-regulating neurons. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;290:R1387–R1396. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00530.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Miyake SI, Wakita H, McMullen DC, Azuma Y, Auh S, Hallenbeck JM. Protein SUMOylation is massively increased in hibernation torpor and is critical for the cytoprotection provided by ischemic preconditioning and hypothermia in SHSY5Y cells. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:950–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler CW, Parfenova H, Jaggar JH, Wang R. Carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide: gaseous messengers in cerebrovascular circulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006;100:1065–1076. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00793.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gao XB, Sakurai T, van den Pol AN. Hypocretin/orexin excites hypocretin neurons via a local glutamate neuron – a potential mechanism for orchestrating the hypothalamic arousal system. Neuron. 2002;36:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZW, Gao XB. Adenosine inhibits activity of hypocretin/orexin neurons via A1 receptor in the lateral hypothalamus: a possible sleep-promoting effect. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;97:837–848. doi: 10.1152/jn.00873.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman CP. Oxygen consumption, body temperature and heart rate of woodchucks entering hibernation. Am. J. Physiol. 1958;194:83–91. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1958.194.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman CP, editor. The hibernating state, Recent theories of hibernation. Academic Press; New York: 1982. pp. 12–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lyman CP, O’Brien RC. Autonomic control of circulation during the hibernating cycle in ground squirrels. J. Physiol. 1963;168:477–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamady H, Storey KB. Up-regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone GRP78 during hibernation in thirteen-lined ground squirrels. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2006;292:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron RM, Sieckmann DG, Yu EZ, Frerichs K, Hallenbeck JM, editors. Hibernation, a state of natural tolerance to profound reduction in organ blood flow and oxygen delivery capacity. Bios Scientific Publishers; Oxford: 2001. pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney M, Jacksonville MC. Brain cholinergic vulnerability: relevance to behavior and disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;70:1115–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LP, Hsu C. Therapeutic potential for adenosine receptor activation in ischemic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1992;9(Suppl. 2):S563–S577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Cao VH, Heller HC. Thermal effects on neuronal activity in suprachiasmatic nuclei of hibernators and nonhibernators. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:R1259–R1266. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK, Burlington RF, Burleson ML. Vagal influence on heart-rate in hibernating ground-squirrels. J. Exp. Biol. 1993;185:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Milsom WK, Zimmer MB, Harris MB. Regulation of cardiac rhythm in hibernating mammals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1999;124:383–391. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(99)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz EM, Marvel CL, Gillespie CF, Price KM, Albers HE. Activation of NMDA receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus produces light-like phase shifts of the circadian clock in vivo. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5124–5130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05124.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohns EJ, Karlsson KA, Blumberg MS. The preoptic hypothalamus and basal forebrain play opposing roles in the descending modulation of sleep and wakefulness in infant rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:1301–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MM, McFarland K, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW, Seamans JK. Cystine/glutamate exchange regulates metabotropic glutamate receptor presynaptic inhibition of excitatory transmission and vulnerability to cocaine seeking. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6389–6393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1007-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutolo D, Bongianni F, Carfi M, Pantaleo T. Respiratory responses to thyrotropin-releasing hormone microinjected into the rabbit medulla oblongata. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:R1331–R1338. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.5.R1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger F. The neuroendocrine system in hibernating mammals: present knowledge and open questions. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:391–412. doi: 10.1007/BF00417858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger F, Zhang Q, Pleschka K, editors. Neuropeptides and neurotransmitters in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: relationship with the hibernation process. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2000. pp. 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara BF, Watson FL, Srere HK, Kumar H, Wiler SW, Welch SK, Bitting L, Heller HC, Kilduff TS. Gene expression in the brain across the hibernation cycle. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:3781–3790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03781.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea JE. Temperature sensitivity of cardiac muscarinic receptors in bat atria and ventricle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 1987;86:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(87)90096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea JE, Evans BK. Innervation of bat heart: cholinergic and adrenergic nerves innervate all chambers. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;249:H876–H882. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.4.H876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne PG, Hashimoto M. State-dependent regulation of cortical blood flow and respiration in hamsters: response to hypercapnia during arousal from hibernation. J. Physiol. 2003;547:963–970. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne PG, Hu Y, Covey DN, Barnes BN, Katz Z, Drew KL. Determination of striatal extracellular gamma-aminobutyric acid in non-hibernating and hibernating arctic ground squirrels using quantitative microdialysis. Brain Res. 1999;839:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz G, Berkich DA, Henry PG, Xu Y, LaNoue K, Hutson SM, Gruetter R. Neuroglial metabolism in the awake rat brain: CO2 fixation increases with brain activity. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:11273–11279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3564-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakhotin PI, Pakhotina ID, Belousov AB. The study of brain slices from hibernating mammals in vitro and some approaches to the analysis of hibernation problems in vivo. Prog. Neurobiol. 1993;40:123–161. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90021-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastukhov YF. REM sleep as a criterion of temperature comfort and temperature homeostasis “well-being” in euthermic and hibernating mammals. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1997;813:71–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengelley ET, Asmundson SJ, Barnes B, Aloia RC. Relationship of light intensity and photoperiod to circannual rhythmicity in the hibernating ground squirrel, Citellus lateralis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 1976;53:273–277. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(76)80035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, McCarley RW. Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science. 1997;276:1265–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulawa LK, Florant GL. The effects of caloric restriction on the body composition and hibernation of the golden-mantled ground squirrel (Spermophilus lateralis) Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2000;73:538–546. doi: 10.1086/317752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AP, Christian SL, Zhao HW, Drew KL. Persistent tolerance to oxygen and nutrient deprivation and N-methyl-d-aspartate in cultured hippocampal slices from hibernating Arctic ground squirrel. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1148–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Dark J, Heller HC, Zucker I. Ablation of suprachiasmatic nucleus alters timing of hibernation in ground squirrels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9864–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Dark J, Heller HC, Zucker I. Suprachiasmatic nucleus: role in circannual body mass and hibernation rhythms of ground squirrels. Brain Res. 1998;782:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby NF, Dark J, Burns DE, Heller HC, Zucker I. The suprachiasmatic nucleus is essential for circadian body temperature rhythms in hibernating ground squirrels. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:357–364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00357.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallmen T, Beckman AL, Stanton TL, Eriksson KS, Tarhanen J, Tuomisto L, Panula P. Major changes in the brain histamine system of the ground squirrel Citellus lateralis during hibernation. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1824–1835. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01824.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallmen T, Lozada AF, Beckman AL, Panula P. Intrahippocampal histamine delays arousal from hibernation. Brain Res. 2003a;966:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallmen T, Lozada AF, Anichtchik OV, Beckman AL, Panula P. Increased brain histamine H3 receptor expression during hibernation in golden-mantled ground squirrels. BMC Neurosci. 2003b;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallmen T, Lozada AF, Anichtchik OV, Beckman AL, Leurs R, Panula P. Changes in hippocampal histamine receptors across the hibernation cycle in ground squirrels. Hippocampus. 2003c;13:745–754. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SS, Gibson GE, Cooper AJ, Denton TT, Thompson CM, Bunik VI, Alves PM, Sonnewald U. Inhibitors of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex alter [1-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamate metabolism in cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006;83:450–458. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan TS, Suchland KL, Hart ME, et al. 3-Iodothyronamine is an endogenous and rapid-acting derivative of thyroid hormone. Nat. Med. 2004;10:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nm1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JE, Friedenson DG, Hall AJ, Wade GN. Glucoprivation induces anestrus and lipoprivation may induce hibernation in Syrian hamsters. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:R573–R577. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.3.R573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibao C, Gamboa A, Diedrich A, Ertl AC, Chen KY, Byrne DW, Farley G, Paranjape SY, Davis SN, Biaggioni I. Autonomic contribution to blood pressure and metabolism in obesity. Hypertension. 2007;49:27–33. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251679.87348.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani M, Tamura Y, Monden M, Shiomi H. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone induced thermogenesis in Syrian hamsters: site of action and receptor subtype. Brain Res. 2005;1039:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi H, Tamura Y. Pharmacological aspects of mammalian hibernation: Central thermoregulation factors in hibernation cycle. Folia Pharmacol. Jpn. 2000;116:304–312. doi: 10.1254/fpj.116.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberger H, Nikmanesh FG, Igelmund P. Long-term potentiation at low temperature is stronger in hippocampal slices from hibernating Turkish hamsters compared to warm-acclimated hamsters and rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;194:127–129. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11723-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]