Abstract

Background Most public health literature on trends in population health and health inequities pertains to observed or targeted changes in rates or proportions per year or decade. We explore, in novel analyses, whether additional insight can be gained by using the ‘haldane’, a metric developed by evolutionary biologists to measure change in traits in standard deviations per generation, thereby enabling meaningful comparisons across species and time periods.

Methods We analysed the phenotypic embodied traits of body height, weight and body mass index of US-born White and Black non-Hispanic adults ages 20 to 44 as measured in six large nationally representative population samples spanning from the 1959–1962 National Health Examination Survey I to the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Setting the former as baseline, we computed the haldane for each outcome for each racial/ethnic group for each survey, overall and stratified by family income quintile.

Results For height, high rates of phenotypic change (haldane ≥ 0.3) occurred chiefly between 1960 and 1980, especially for the Black population in the higher income quintiles. By contrast, for weight, high rates of phenotypic change became evident for both the White and Black populations in the late 1980s and increased thereafter; for body mass index, the shift to high rates of change started in both groups in the late 1990s, especially in the middle income quintiles.

Conclusions Our results support use of the haldane as a supplemental metric to place changes in population health and health inequities in a larger biological and historical context.

Keywords: Body mass index, epidemiology, evolution, health status disparities, height, history, nutrition surveys, phenotype, socioeconomic factors, weight

Introduction

Critical clues regarding the causes—and prevention—of disease have repeatedly been found through study of changes in population rates and the magnitude of health inequities they manifest.1–4 At issue is not only whether on-average rates and inequities are rising, shrinking, reversing or stagnating,4–6 but also the speed at which these changes are taking place. Trends or targets typically are reported as an observed or targeted average annual percent change or absolute or relative change in rates or proportions per year or decade.7,8

Might, however, there be an alternative approach to measuring rates of change, one more attuned to the social and biological processes at play? One possibility is a metric formulated in the field of evolutionary biology, developed to gauge the tempo of biological change. Termed the ‘haldane’,9,10 this measure is named after the eminent and broadly historically-minded British biologist JBS Haldane (1892–1964),11,12 and has been used to assess change in both phenotypic and genotypic traits.9,10,13

Conceptually, the haldane may be defined as the absolute change in standard deviations (SD) of a trait per generation;9,10,13 in effect, it is the effect size14 divided by the N of generations. Scaling to generation is key, because it provides a biologically (and socially) meaningful referent that enables comparison across time periods and across species ‘to understand how a population responds to environmental change’.10 Haldane first proposed a measure along these lines in 1949 (Textbox 1),15 which Gingerich dubbed the ‘haldane’ in 1993,9 and which in 1999 Hendry and Kinnison innovatively deployed10,16 to investigate if anthropogenic-induced environmental change (i.e. changes in the pace, scale, intensity, duration and types of exposures due to human intervention) was driving haldanes to values exceeding those typically observed in non-anthropogenic contexts (usual range: ∼0 to 0.2, with a modal value of ∼0.1).9,10,17

Box 1 The origin and definition of the haldane.

Origin of the haldane

The concept of quantifying rates of evolutionary change was initially proposed by JBS Haldane in 1949 in his paper ‘Suggestions as to quantitative measurement of rates of evolution,’15 for which the summary states:

p. 56: ‘Suggestions are made for the measurement of evolutionary rates of metrical characters. The unit of time may be the year or the generation. The unit for the character may be a unit increase in the natural logarithm of the variate, or alternatively one standard deviation of the character in a population at a given horizon. Examples are given from mammalian paleontology of the calculation of such rates.’

The statement in which Haldane described the new measure he proposed is as follows:

p. 55: ‘It may be found desirable to coin some word, for example a ‘darwin’, for a unit of evolutionary rate, such as an increase or decrease of size by a factor of e per million years, or what is practically equivalent, an increase or decrease of 1/1000 per 1000 years. If so the horse rates would range round 40 millidarwins and rates under a millidarwin would be hard to measure. Rates of one darwin would be exceptional. But domesticated animals and plants have changed at rates measured in kilodarwins, though not megadarwins.’

In 1993, Philip D Gingerich formally defined the metric of the ‘haldane’ in his paper ‘Quantification and comparison of evolutionary rates’,9 in which he wrote:

p. 457: ‘Quantification in terms of phenotypic standard deviations… has two advantages over quantification in darwins. These are: (1) phenotypic standard deviations are natural measures of normally-distributed variation for traits under study, and (2) standard deviations are themselves dimension-dependent, meaning that rates of change calculated in standard deviation units are dimensionless and also dimension-independent in the sense that rates for areas, for volumes, and for shape quotients can all be compared directly with rates of change of linear measurements… one haldane here is defined as change by a factor of one standard deviation per generation. Calibration of evolutionary rates in haldanes is advantageous over calibration in darwins in that: (1) standard deviations are natural measures of variation, (2) generations are natural counts of reproductive rather than planetary cycles, and (3) rates calculated in standard deviations per generation are both dimensionless and dimension-independent.’

Technical definition of the haldane

Mathematically, the haldane,10 which measures ‘rates in phenotypic standard deviations per generation’,9 is expressed as:

where

and h = haldane, g = number of generations, mt2 = mean value at time 2, mt1 = mean value at time 1, n2 = size of the population at time 2, n1 = size of the population at time1, s22 = variance at time 2, and s12 = variance at time 1.

As the formula indicates, the haldane’s value depends on both the magnitude of the effect size (the numerator) and the N of generations observed (the denominator). Thus, if the numerator were, say, 0.6, and the N of generations equalled 2, the haldane would be equal to 0.3 (i.e. a change of 0.3 SD per generation); if the N of generations equalled 12, the haldane would be much smaller, equal only to 0.05 (i.e. a change of 0.05 SD per generation).

To clarify the relevant focus of analysis and its temporal frame, the haldane is denoted with subscripts, whereby p refers to phenotype, g refers to genotype, and the N of generations is enclosed in parentheses, e.g. for an analysis of a change in phenotypic trait spanning 1.5 generations, the notation would be hp(1.5).10 In the published literature, values of the haldane typically range between 0.0 and 0.2 (with a modal value of 0.1).9,10,17

KEY MESSAGES.

Most public health literature on trends in population health and health inequities pertains to observed or targeted changes in rates or proportions per year or decade.

We explore, in novel analyses, whether additional insight can be gained by using the ‘haldane’, a metric developed by evolutionary biologists to measure change in traits in standard deviations per generation, thereby enabling meaningful comparisons across species and time periods.

Our analyses, based on US-born White non-Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic participants in six cross-sectional US nationally representative surveys spanning from the National Health Examination Survey I (1959–1962) to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2008, show that: (1) for height, high rates of phenotypic change occurred chiefly between 1960 and 1980, especially for the Black population in the higher income quintiles, whereas (2) for weight, high rates of phenotypic change became evident for both the White and Black populations in the late 1980s and increased thereafter, and (3) for BMI, the shift to high rates of change started in both groups in the late 1990s, especially in the middle income quintiles.

Taken together, our results support use of the haldane as a supplemental metric to place changes in population health and health inequities in a larger biological and historical context.

To our knowledge, only two studies have employed the haldane with contemporary human data. The first, appearing in 2009, was based on US data published in 1932 and estimated, for analyses spanning two generations, that the rate of change for height was 0.1 SD per generation (i.e. 0.1 haldanes).17 The second, published in 2010, estimated haldane values for 10 generations from now for cardiovascular risk factors among offspring of the 1948 Framingham heart disease cohort; projected values ranged from lows of 0.002 for diastolic blood pressure and 0.007 for weight up to 0.020 for age at menopause and 0.032 for height.18

In this study, informed by the ecosocial theory of disease distribution and its focus on how people literally biologically embody their societal and ecologic context, at multiple levels, across the lifecourse and historical generations,4,19,20 we accordingly explored application of the haldane to three interrelated outcomes of public health interest: height, weight and body mass index (BMI).21–26 All three outcomes are at play in recent global increases in obesity and its societal distribution within and across countries22–25 and all also can be meaningfully conceptualized as embodied phenotypic traits shaped by societal context.21

Our a priori hypotheses were that haldanes for weight and BMI would be higher than for height and also be more likely to reach high values akin to those observed among wildlife for anthropogenic-induced environmental change.10,16 A corollary was that patterns of change would vary by both race/ethnicity and income level.

Methods

Study population

We analysed anthropometric data spanning from 1959 to 2008 using data from the one extant long-term US health database with consistent individual-level data on measured health characteristics and socioeconomic position: the National Health Examination Survey (NHES)27 and its successor, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Studies (NHANES).28 Both are nationally representative cross-sectional samples of the US non-institutionalized civilian population; extensive documentation on their survey design, data collection and sampling weights are available online.27,28

For our analyses, we restricted the age distribution to adults 20–44 years old, so as to enable comparison of trends among similarly aged adults who have attained their adult stature and among whom reduced weight or height is unlikely to be due to morbidity (e.g. cancer, osteoporosis).29 To avoid confounding by immigration status,26 we additionally restricted the study population to US-born White and Black non-Hispanic persons as feasible,30 as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study population of US-born White non-Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic adults ages 20–44 and corresponding US family income quintiles (in 2010 CPI-UR-S adjusted dollars) for mid-point of each survey: US National Health Examination Survey (NHES) I (1959–1962) through US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2008

| Variable | Race/ ethnicity | NHES I (1959–1962) | NHANES I (1971–1975) | NHANES II (1976–1980) | NHANES III (1988–1994) | NHANES (1999–2004) | NHANES (2005–2008) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of person in survey (N, actual) | US-born White (non- Hispanic)a | 3046 | 3943 | 3591 | 2251 | 2582 | 1768 | ||||

| US-born Black (non- Hispanic)a | 444 | 1179 | 597 | 2528 | 1173 | 889 | |||||

| Estimated size of corresponding US population (N, weighted) | US-born White (non- Hispanic)a | 49 090 540 | 43 492 218 | 52 720 298 | 66 838 819 | 62 019 989 | 60 654 819 | ||||

| US-born Black (non- Hispanic)a | 5 950 472 | 6 758 456 | 7 891 261 | 11 433 497 | 11 106 415 | 11 459 499 | |||||

| Survey mid-pointb | 1961 | 1972.5 | 1978 | 1991.5 | 2002 | 2007 | |||||

| Years between survey mid-points | (referent) | 11.5 | 17.0 | 30.5 | 41.0 | 46.0 | |||||

| Generationsc elapsed since NHES I | (referent) | 0.575 | 0.850 | 1.525 | 2.050 | 2.300 | |||||

| US family income quintile (Q: in 2010 CPI-UR-S adjusted dollars)d | Total population | Phase I (1989–1991) | Phase II (1991–1994) | NHANES 1999–2000 | NHANES 2001–2002 | NHANES 2003–2004 | NHANES 2005–2006 | NHANES 2007–2008 | |||

| Q1 (lowest) | ≤ $17 860 | ≤ $26 415 | ≤ $27 015 | ≤ $27 243 | ≤ $25 215 | ≤ $30 387 | ≤ $29 087 | ≤ $28 594 | ≤ $29 198 | ≤ $28 152 | |

| Q2 | $17 861– $30 744 | $26 416– $43 679 | $27 016– $45 392 | $27 244– $46 969 | $25 216– $44 575 | $30 388– $51 708 | $29 088– $50 224 | $28 595– $50 096 | $29 199– $50 825 | $28 153– $49 949 | |

| Q3 | $30 745– $41 843 | $43 680– $60 662 | $45 394– $63 549 | $46 970– $67 986 | $44 576– $66 908 | $51 709– $77 644 | $50 225– $76 354 | $50 097– $75 973 | $50 826– $76 995 | $49 950– $75 949 | |

| Q4 | $41 844– $57 630 | $60 663– $83 613 | $63 550– $88 331 | $67 987– $99 440 | $66 909– $99 246 | $77 645– $115 690 | $76 355– $114 493 | $75 974– $115 429 | $76 996– $118 034 | $75 950– $114 637 | |

| Q5 (highest) | ≥ $57 631 | ≥ $83 614 | ≥ $88 332 | ≥ $99 441 | ≥ $99 247 | ≥ $115 691 | ≥ $114 494 | ≥ $115 430 | ≥ $118 035 | ≥ $114 638 | |

aNativity and race/ethnicity:

(1) for all surveys other than NHES I, data were available on nativity; for NHES I, US census data indicate that in 1960, 94.1% of US Whites were US-born and 99.3% of US Blacks were US-born30;

(2) for the US White population, data on Hispanic origin were available to categorize persons who were ‘White non-Hispanic starting with NHANES III; for NHES I, no data were available on Hispanic origin; for NHANES I, we defined ‘White non-Hispanic’ as White persons who reported the following ancestry groups: ‘German,’ ‘Irish,’ ‘Italian,’ ‘French,’ ‘Polish,’ ‘Russian,’ English, ‘Jewish,’ and ‘American’ (and excluded persons who listed their ancestry as: ‘Spanish,’ ‘Mexican,’ ‘Chinese,’ ‘Japanese,’ ‘American Indian,’ ‘Negro,’ ‘Other,’ ‘Blank but applicable’ (only 0.4%), and ‘Don’t know’ (3%)); and for NHANES II, we defined ‘White non-Hispanic’ as persons who reported their ancestry was ‘Other European, such as German, French, English, Irish’ (and excluded person who listed their ancestry as: ‘countries of Central or South America,’ ‘Chicano,’ ‘Cuban,’ ‘Mexican,’ ‘Mexican-American,’ ‘Puerto Rican,’ ‘Other Spanish,’ ‘Black, Negro, or Afro-American,’ ‘American Indian or Alaskan Native,’ ‘Asian Pacific Islander, such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Phillipino,’ ‘Another group not listed,’ and’ Blank but applicable’ (only 2.4%));

(3) for the US Black population, data on Hispanic origin were available to categorize persons who were ‘Black non-Hispanic’ from 1999 onwards; US census data indicate that the percentage of the Black population that was non-Hispanic was, in 1970, 98.6%, in 1980, 98.5% and in 1990, 97.4%.30

bSurvey mid-point as defined in the NHES and NHANES technical documentation27,28; for surveys conducted in two phases (e.g. NHANES III) or which were conducted separately but which we combined (e.g. NHANES 1999–2000 + 2001–2002 + 2003–2004, and NHANES 2005–2006 + 2007–2008), we assigned individuals the income quintile for the survey in which they were examined and then combined results across component surveys.

cGeneration defined as 20 years.

dSource: US Bureau of Census (Current Population Survey data).34

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants in NHES and NHANES at the time of each survey.27,28 Because our analyses are based solely on publicly available de-identified pre-existing coded data, our study was exempted from Institutional Review Board review by the Harvard School of Public Health Human Subjects Committee (HSC Protocol #P16105-101, 15 May 2008).

Study variables

Data on height (m) and weight (kg), obtained using validated anthropometric protocols,27,28 were used to compute BMI (kg/m2). The proportion of the study population missing data for these three variables was low: 0% in NHES I, NHANES I and NHANES II; under 0.2% in NHANES III; and ∼5 to 7% for NHANES 1999–2004 and 2005–2008.

The only two socioeconomic measures available consistently across all surveys were family income and educational level. In our analyses we focused on income, so as to avoid the problem of changes in the meaning of educational credentials and their associated earnings over time (e.g. an adult whose educational attainment in 1960 equalled high school graduate had better employment prospects and higher relative earnings compared with someone with only a high school degree in 2008; during this same time period the college wage premium also increased considerably31–33).

We demarcated family income quintiles using data from the Current Population Survey,34 whose dollars were set to 2010 values adjusted to the US Census Bureau Average Consumer Price Index Series Using Current Methods (CPI-UR-S). We then assigned each survey participant to the US yearly family income quintile (Q1: lowest; Q5: highest) that encompassed the mid-point of her/his pre-categorized family income brackets for the survey’s mid-point year, as defined in the technical documentation27,28 (see Table 1). The proportion of the study population missing data for family income was modest, ranging from a low of 3% in NHANES II to a high of 9% for NHANES 1999–2004 (Table 1).

Data analysis

We analysed data separately for the White and Black participants, using both the unweighted and weighted data (taking into account survey design), and report only the weighted data. For each racial/ethnic group, we first determined the survey participants’ average height, weight and BMI and their associated SD, both overall and by income quintile. We also log-transformed (ln) these data, given arguments that analysing relative (or percent) difference, as opposed to absolute difference, is more appropriate for evaluating change in biological traits and their variation, especially for morphological parameters9,10,15–17—both because changes are relative to baseline (i.e. a change of 0.5 cm for a bone originally 1 cm vs originally 30 cm is not equivalent) and also because the likely underlying processes of growth (or shrinkage) may produce a log-normal distribution.10,17

Following standard practice for biological field studies,9,10,16,17 we set the earliest survey (NHES I, 1959-1962) as baseline and then computed the haldane on both the absolute and log scale (corresponding to an absolute and relative difference). For these analyses, we set generation length equal to 20 years, based on trends in the mean and median age at first birth in the US and their variation by education level.35–37 Informed by extant literature regarding usual values of the haldane,9,10,17 we denote haldane values ≥ 0.2 and <0.3 as intermediate high values, and those ≥ 0.3 as high values. For comparisons with prior literature, we also computed the conventional absolute difference and relative ratio, with confidence intervals (CI) calculated using standard errors that appropriately took into account survey weighting and design; these data are available upon request. We performed all analyses in SAS.38

Results

To situate each survey temporally, Table 1 presents data on the survey mid-point and both the number of years and number of generations elapsed between each survey and the NHES I baseline; it also provides data on the number of US-born White and Black non-Hispanic persons examined (on average 2863 and 1135 per survey, respectively), the estimated size of the corresponding US population (on average 55.8 and 9.1 million persons, respectively), and the family income quintiles boundaries. Overall, 46 years elapsed between the mid-points of NHES I and NHANES 2005–2008.

Table 2 next presents the actual and log-transformed values for height, weight and BMI across the surveys. As has been previously documented,23,25,26,39–44 the on-average height, weight and BMI within the study age group (20–44 years old) increased across the surveys, comparing NHANES 2005–2008 with NHES I (1959–1962), as did the standard deviation for both weight and BMI (but not height) (Table 2). For height, the on-average absolute increase was ∼ 3 to 5 cm for both the White and Black populations; for weight, it was on average ∼13 kg for the White population and ∼16 kg for the Black population; and for BMI, it was on average ∼3.5 kg/m2 for the White population and ∼4.5 kg/m2 for the Black population, with patterns modestly varying by income quintile within each racial/ethnic group.

Table 2.

Average height, weight and BMI of the US-born White non-Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic adults age 20–44, overall and by US family income quintile: US National Health Examination Survey (NHES) I (1959–1962) through US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2008

| NHES I (1959–1962) |

NHANES I (1971–1975) |

NHANES II (1976–1980) |

NHANES III (1988–1994) |

NHANES (1999–2004) |

NHANES (2005–2008) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

||||||||

| Body size | Population group | Actual | Log- transformed | Actual | Log- transformed | Actual | Log- transformed | Actual | Log- transformed | Actual | Log- transformed | Actual | Log- transformed |

| US-born White (non-Hispanic)a | |||||||||||||

| Height (m) | Total income quintile (Q) | 1.6798 | 0.5172 | 1.7009 | 0.5296 | 1.7066 | 0.5330 | 1.7079 | 0.5337 | 1.7152 | 0.5380 | 1.7162 | 0.5280 |

| (0.0915) | (0.0544) | (0.0945) | (0.0554) | (0.0939) | (0.0550) | (0.0957) | (0.0561) | (0.0964) | (0.0561) | (0.0951) | (0.0583) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 1.6644 | 0.5077 | 1.6951 | 0.5261 | 1.6964 | 0.5270 | 1.6932 | 0.5252 | 1.6998 | 0.5289 | 1.7116 | 0.5137 | |

| (0.0984) | (0.0584) | (0.0975) | (0.0572) | (0.0935) | (0.0550) | (0.0916) | (0.0541) | (0.0965) | (0.0565) | (0.0935) | (0.0564) | ||

| Q2 | 1.6656 | 0.5087 | 1.6945 | 0.5258 | 1.7004 | 0.5294 | 1.7089 | 0.5342 | 1.7131 | 0.5367 | 1.7185 | 0.5247 | |

| (0.0916) | (0.0550) | (0.0942) | (0.0555) | (0.0925) | (0.0544) | (0.0973) | (0.0570) | (0.0964) | (0.0560) | (0.0935) | (0.0584) | ||

| Q3 | 1.6802 | 0.5174 | 1.7052 | 0.5322 | 1.7145 | 0.5377 | 1.7111 | 0.5355 | 1.7222 | 0.5421 | 1.7123 | 0.5302 | |

| (0.0912) | (0.0542) | (0.0932) | (0.0546) | (0.0901) | (0.0527) | (0.1000) | (0.0585) | (0.0938) | (0.0547) | (0.0924) | (0.0581) | ||

| Q4 | 1.6823 | 0.5187 | 1.7033 | 0.5311 | 1.7057 | 0.5324 | 1.7052 | 0.5322 | 1.7279 | 0.5455 | 1.7094 | 0.5345 | |

| (0.0909) | (0.0538) | (0.0928) | (0.0545) | (0.0957) | (0.0563) | (0.0906) | (0.0533) | (0.0910) | (0.0529) | (0.0993) | (0.0567) | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 1.6902 | 0.5234 | 1.7185 | 0.5399 | 1.7189 | 0.5401 | 1.7141 | 0.5374 | 1.7226 | 0.5422 | 1.7237 | 0.5378 | |

| (0.0903) | (0.0535) | (0.0957) | (0.0556) | (0.0980) | (0.0570) | (0.0942) | (0.0551) | (0.0980) | (0.0567) | (0.0982) | (0.0582) | ||

| Weight (kg) | Total income quintile | 69.2126 | 4.2159 | 71.1883 | 4.2406 | 71.4709 | 4.2464 | 74.9768 | 4.2877 | 80.6351 | 4.3581 | 82.3086 | 4.3657 |

| (14.5820) | (0.2053) | (16.2226) | (0.2207) | (15.6294) | (0.2130) | (19.0139) | (0.2395) | (21.0555) | (0.2498) | (22.2086) | (0.2536) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 67.2296 | 4.1848 | 70.4224 | 4.2287 | 68.5445 | 4.2069 | 73.9147 | 4.2711 | 78.9715 | 4.3319 | 81.3418 | 4.3409 | |

| (15.2314) | (0.2117) | (16.7552) | (0.2235) | (14.5858) | (0.1995) | (19.6943) | (0.2480) | (22.5859) | (0.2687) | (25.8464) | (0.2768) | ||

| Q2 | 68.7997 | 4.2104 | 70.9372 | 4.2358 | 70.7642 | 4.2350 | 74.0064 | 4.2758 | 81.7702 | 4.3728 | 82.0803 | 4.3724 | |

| (14.4375) | (0.2020) | (16.6799) | (0.2260) | (15.9468) | (0.2195) | (18.7012) | (0.2340) | (20.8041) | (0.2484) | (20.7034) | (0.2424) | ||

| Q3 | 70.1853 | 4.2297 | 71.8615 | 4.2508 | 73.3446 | 4.2739 | 76.4292 | 4.3055 | 82.4173 | 4.3808 | 84.3408 | 4.3850 | |

| (14.7100) | (0.2064) | (15.9111) | (0.2183) | (15.3433) | (0.2060) | (19.4937) | (0.2471) | (21.6530) | (0.2446) | (21.7890) | (0.2584) | ||

| Q4 | 69.2434 | 4.2159 | 71.5861 | 4.2466 | 71.8688 | 4.2501 | 75.9237 | 4.3025 | 81.6913 | 4.3758 | 81.6745 | 4.3875 | |

| (14.8756) | (0.2067) | (16.0406) | (0.2198) | (16.1486) | (0.2223) | (18.5236) | (0.2299) | (19.2877) | (0.2327) | (20.2219) | (0.2379) | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 69.7360 | 4.2241 | 71.9935 | 4.2550 | 72.8771 | 4.2674 | 74.6460 | 4.2847 | 79.8097 | 4.3520 | 81.2542 | 4.3497 | |

| (14.2454) | (0.2030) | (15.2257) | (0.2069) | (15.4224) | (0.2050) | (18.5136) | (0.2339) | (19.1456) | (0.2344) | (20.6934) | (0.2462) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Total income quintile | 24.4383 | 3.1814 | 24.4846 | 3.1813 | 24.4436 | 3.1804 | 25.5747 | 3.2203 | 27.2794 | 3.2818 | 27.8580 | 3.3097 |

| (4.3887) | (0.1689) | (4.7256) | (0.1791) | (4.6112) | (0.1749) | (5.6783) | (0.2007) | (6.3121) | (0.2169) | (6.9372) | (0.2230) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 24.2783 | 3.1693 | 24.4591 | 3.1765 | 23.8681 | 3.1529 | 25.6923 | 3.2207 | 27.2026 | 3.2733 | 27.7611 | 3.3134 | |

| (5.2647) | (0.1953) | (5.3695) | (0.1963) | (5.2736) | (0.1895) | (6.2603) | (0.2190) | (6.9777) | (0.2408) | (8.6669) | (0.2572) | ||

| Q2 | 24.7919 | 3.1930 | 24.6051 | 3.1841 | 24.3740 | 3.1762 | 25.2335 | 3.2073 | 27.7145 | 3.2984 | 27.7460 | 3.3231 | |

| (4.9046) | (0.1829) | (5.0876) | (0.1895) | (4.7510) | (0.1822) | (5.5587) | (0.1978) | (6.2025) | (0.2145) | (6.5367) | (0.2210) | ||

| Q3 | 24.7693 | 3.1947 | 24.5679 | 3.1864 | 24.8487 | 3.1984 | 25.9260 | 3.2346 | 27.6762 | 3.2964 | 28.6497 | 3.3246 | |

| (4.3948) | (0.1706) | (4.3915) | (0.1716) | (4.4015) | (0.1671) | (5.5060) | (0.1998) | (6.4769) | (0.2149) | (6.6017) | (0.2275) | ||

| Q4 | 24.3506 | 3.1784 | 24.4967 | 3.1844 | 24.5335 | 3.1852 | 26.0711 | 3.2381 | 27.2499 | 3.2852 | 27.7892 | 3.3185 | |

| (4.3106) | (0.1654) | (4.2986) | (0.1654) | (4.3946) | (0.1694) | (6.3174) | (0.2025) | (5.5892) | (0.1973) | (5.7460) | (0.2014) | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 24.2852 | 3.1771 | 24.2437 | 3.1753 | 24.5471 | 3.1873 | 25.2493 | 3.2098 | 26.7557 | 3.2673 | 27.1974 | 3.2740 | |

| (4.0061) | (0.1574) | (4.0727) | (0.1581) | (4.2087) | (0.1598) | (5.2651) | (0.1900) | (5.5377) | (0.1933) | (6.0736) | (0.2007) | ||

| US-born Black (non-Hispanic)a | |||||||||||||

| Height (m) | Total income quintile | 1.6647 | 0.5082 | 1.6806 | 0.5177 | 1.6897 | 0.5230 | 1.6981 | 0.5280 | 1.6983 | 0.5280 | 1.7024 | 0.5304 |

| (0.0892) | (0.0536) | (0.0926) | (0.0549) | (0.0959) | (0.0567) | (0.0940) | (0.0552) | (0.0989) | (0.0582) | (0.0961) | (0.0564) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 1.6577 | 0.5041 | 1.6695 | 0.5109 | 1.6647 | 0.5080 | 1.6883 | 0.5222 | 1.6857 | 0.5206 | 1.6930 | 0.5251 | |

| (0.0857) | (0.0515) | (0.0960) | (0.0568) | (0.0960) | (0.0575) | (0.0922) | (0.0546) | (0.0964) | (0.0570) | (0.0913) | (0.0536) | ||

| Q2 | 1.6652 | 0.5087 | 1.6876 | 0.5218 | 1.6894 | 0.5228 | 1.6999 | 0.5291 | 1.7013 | 0.5296 | 1.6980 | 0.5277 | |

| (0.0833) | (0.0502) | (0.0916) | (0.0543) | (0.0942) | (0.0557) | (0.0940) | (0.0548) | (0.1002) | (0.0588) | (0.0989) | (0.0586) | ||

| Q3 | 1.6699 | 0.5114 | 1.6887 | 0.5228 | 1.7012 | 0.5302 | 1.7046 | 0.5318 | 1.7159 | 0.5383 | 1.7089 | 0.5342 | |

| (0.0863) | (0.0519) | (0.0815) | (0.0482) | (0.0830) | (0.0490) | (0.0943) | (0.0554) | (0.0972) | (0.0568) | (0.0989) | (0.0576) | ||

| Q4 | 1.6622 | 0.5067 | 1.7005 | 0.5293 | 1.7270 | 0.5442 | 1.7202 | 0.5410 | 1.7074 | 0.5331 | 1.7186 | 0.5403 | |

| (0.0899) | (0.0548) | (0.0945) | (0.0562) | (0.1149) | (0.0661) | (0.0922) | (0.0538) | (0.1041) | (0.0615) | (0.0842) | (0.0492) | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 1.6651 | 0.5081 | 1.6961 | 0.5274 | 1.7197 | 0.5410 | 1.7092 | 0.5344 | 1.7215 | 0.5416 | 1.7168 | 0.5389 | |

| (0.0991) | (0.0591) | (0.0743) | (0.0441) | (0.0814) | (0.0473) | (0.0986) | (0.0575) | (0.0985) | (0.0573) | (0.0963) | (0.0564) | ||

| Weight (kg) | Total income quintile | 71.8347 | 4.2511 | 73.6341 | 4.2691 | 73.2388 | 4.2682 | 79.2486 | 4.3420 | 86.2300 | 4.4214 | 88.0924 | 4.4417 |

| (15.8471) | (0.2145) | (19.2102) | (0.2404) | (17.1028) | (0.2238) | (20.5380) | (0.2438) | (24.1452) | (0.2631) | (24.9315) | (0.2674) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 69.2962 | 4.2147 | 72.5575 | 4.2502 | 69.7784 | 4.2184 | 77.3394 | 4.3155 | 85.4224 | 4.4105 | 86.9275 | 4.4231 | |

| (15.5613) | (0.2157) | (19.8764) | (0.2572) | (16.6863) | (0.2303) | (21.2286) | (0.2496) | (24.4017) | (0.2686) | (26.7389) | (0.2841) | ||

| Q2 | 73.2084 | 4.2694 | 74.0307 | 4.2820 | 74.3558 | 4.2805 | 80.1106 | 4.3545 | 87.4619 | 4.4356 | 89.8031 | 4.4609 | |

| (15.8921) | (0.2206) | (15.7184) | (0.2134) | (18.6479) | (0.2340) | (19.7062) | (0.2393) | (24.5396) | (0.2630) | (25.3461) | (0.2684) | ||

| Q3 | 66.7774 | 4.1907 | 71.9699 | 4.2592 | 73.3248 | 4.2763 | 79.7923 | 4.3494 | 83.9278 | 4.4018 | 87.7186 | 4.4427 | |

| (9.8636) | (0.1455) | (13.6465) | (0.1829) | (14.1683) | (0.1929) | (20.3873) | (0.2420) | (21.3080) | (0.2333) | (22.7974) | (0.2481) | ||

| Q4 | 73.9048 | 4.2830 | 82.9290 | 4.3566 | 76.2775 | 4.3148 | 82.4335 | 4.3825 | 89.9423 | 4.4581 | 90.1408 | 4.4638 | |

| (15.1870) | (0.1969) | (33.6631) | (0.3291) | (15.1839) | (0.1979) | (20.0073) | (0.2442) | (26.4978) | (0.2847) | (25.3077) | (0.2714) | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 72.6776 | 4.2638 | 74.5725 | 4.2912 | 75.0868 | 4.3009 | 81.2730 | 4.3740 | 89.0790 | 4.4573 | 89.2535 | 4.4615 | |

| (15.6097) | (0.2093) | (14.6827) | (0.2065) | (14.1465) | (0.1884) | (18.6036) | (0.2145) | (23.8192) | (0.2496) | (22.6177) | (0.2421) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Total income quintile | 25.8804 | 3.2345 | 26.0121 | 3.2337 | 25.6485 | 3.2223 | 27.4516 | 3.2861 | 29.9155 | 3.3652 | 30.3550 | 3.3806 |

| (5.2209) | (0.1920) | (6.1859) | (0.2175) | (5.7392) | (0.2056) | (6.7011) | (0.2244) | (8.1277) | (0.2528) | (8.1654) | (0.2497) | ||

| Q1 (lowest) | 25.2351 | 3.2064 | 26.0003 | 3.2284 | 25.2019 | 3.2024 | 27.1418 | 3.2711 | 30.1348 | 3.3697 | 30.3126 | 3.3721 | |

| (5.6448) | (0.2029) | (6.7125) | (0.2385) | (6.0047) | (0.2152) | (7.1760) | (0.2373) | (8.5165) | (0.2633) | (9.2005) | (0.2725) | ||

| Q2 | 26.3684 | 3.2520 | 25.9467 | 3.2383 | 26.0355 | 3.2349 | 27.6908 | 3.2964 | 30.1859 | 3.3746 | 31.2328 | 3.4054 | |

| (5.3815) | (0.2002) | (4.9455) | (0.1880) | (6.1024) | (0.2168) | (6.4323) | (0.2189) | (8.0800) | (0.2527) | (8.7900) | (0.2646) | ||

| Q3 | 23.9696 | 3.1677 | 25.1931 | 3.2135 | 25.3231 | 3.2160 | 27.4106 | 3.2858 | 28.4520 | 3.3251 | 29.8855 | 3.3744 | |

| (3.2387) | (0.1349) | (4.1800) | (0.1598) | (4.6989) | (0.1734) | (6.4869) | (0.2197) | (6.4697) | (0.2117) | (6.4618) | (0.2146) | ||

| Q4 | 26.6656 | 3.2695 | 28.4488 | 3.2979 | 25.7920 | 3.2265 | 27.7329 | 3.3005 | 30.6557 | 3.3920 | 30.5998 | 3.3833 | |

| (4.5300) | (0.1652) | (10.1738) | (0.3003) | (6.1547) | (0.2085) | (5.8971) | (0.2097) | (7.9092) | (0.2453) | (8.9060) | (0.2690) | ||

| Q5 (highest) | 26.0773 | 3.2475 | 25.8803 | 3.2364 | 25.3165 | 3.2189 | 27.7708 | 3.3054 | 29.9717 | 3.3742 | 30.1130 | 3.3838 | |

| (4.2816) | (0.1656) | (4.9027) | (0.1829) | (4.0471) | (0.1580) | (5.7147) | (0.1881) | (7.3234) | (0.2225) | (6.4247) | (0.2033) | ||

aSee definition of nativity-race/ethnicity groups in footnote to Table 1.

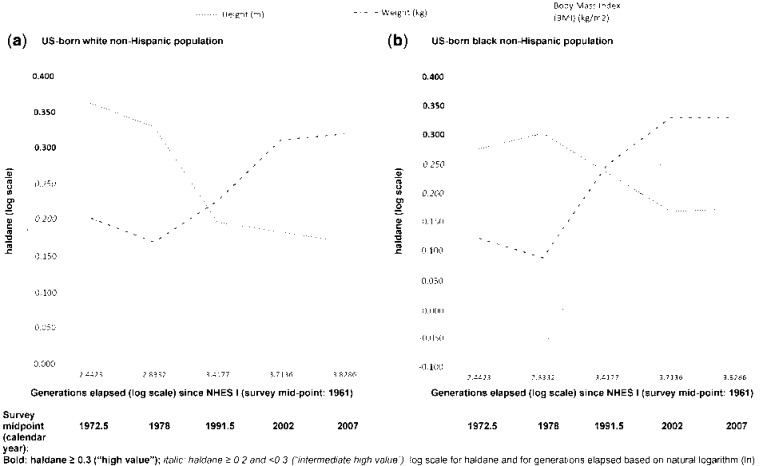

Table 3 and Figure 1 revisit these well-known trends, analysing them using the haldane. Because results on the actual scale and on the log-scale (i.e. relative difference) are virtually identical, our text focuses on the actual haldane results, with Figure 1 illustrating key trends using the log-scale. Our notable findings are as follows.

Table 3.

Trends in average height, weight, and BMI of the US-born white non-Hispanic and black non-Hispanic adults age 20–44, overall and by US family income quintile: haldane (h)b, actual scale and log scale (relative difference), comparing the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) I (1971–1975) through 2005–2008 to the baseline of US National Health Examination Survey (NHES) I (1959–1962)

| NHANES I (1971–1975) compared with NHES 1 (1959–1962) |

NHANES II (1976–1980) compared with NHES 1 (1959–1962) |

NHANES III (1988–1994) compared with NHES 1 (1959–1962) |

NHANES (1999–2004) compared with NHES 1 (1959–1962) |

NHANES (2005–2008) compared with NHES 1 (1959–1962) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

hp(0.575) |

hp(0.850) |

hp(1.525) |

hp(2.050) |

hp(2.300) |

|||||||

| Body size | Population group | actual | log scale | actual | log scale | actual | log scale | actual | log scale | actual | log scale |

| US-born White (non-Hispanic)a | |||||||||||

| Height (m) | Total | 0.363 | 0.363 | 0.330 | 0.330 | 0.197 | 0.198 | 0.184 | 0.184 | 0.170 | 0.171 |

| Income quintile (Q) | |||||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.512 | 0.504 | 0.394 | 0.386 | 0.206 | 0.202 | 0.181 | 0.178 | 0.220 | 0.217 | |

| Q2 | 0.497 | 0.495 | 0.434 | 0.431 | 0.300 | 0.301 | 0.246 | 0.246 | 0.249 | 0.249 | |

| Q3 | 0.434 | 0.432 | 0.436 | 0.433 | 0.208 | 0.210 | 0.221 | 0.221 | 0.152 | 0.152 | |

| Q4 | 0.367 | 0.367 | 0.286 | 0.289 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.244 | 0.245 | 0.126 | 0.128 | |

| Q5 (highest) | 0.487 | 0.493 | 0.347 | 0.352 | 0.169 | 0.170 | 0.167 | 0.169 | 0.155 | 0.157 | |

| Weight (kg) | Total | 0.185 | 0.204 | 0.166 | 0.170 | 0.214 | 0.228 | 0.306 | 0.313 | 0.315 | 0.320 |

| Income quintile | |||||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.318 | 0.311 | 0.124 | 0.102 | 0.239 | 0.239 | 0.279 | 0.270 | 0.296 | 0.263 | |

| Q2 | 0.185 | 0.213 | 0.131 | 0.145 | 0.197 | 0.206 | 0.350 | 0.353 | 0.330 | 0.336 | |

| Q3 | 0.157 | 0.172 | 0.245 | 0.239 | 0.215 | 0.231 | 0.324 | 0.318 | 0.331 | 0.329 | |

| Q4 | 0.232 | 0.244 | 0.184 | 0.195 | 0.268 | 0.277 | 0.369 | 0.386 | 0.326 | 0.347 | |

| Q5 (highest) | 0.242 | 0.249 | 0.243 | 0.244 | 0.185 | 0.202 | 0.289 | 0.301 | 0.285 | 0.306 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Total | −0.001 | 0.016 | −0.007 | 0.001 | 0.139 | 0.150 | 0.255 | 0.259 | 0.271 | 0.272 |

| Income quintile | |||||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.059 | 0.054 | −0.098 | −0.089 | 0.159 | 0.156 | 0.219 | 0.215 | 0.213 | 0.193 | |

| Q2 | −0.076 | −0.059 | −0.105 | −0.100 | 0.049 | 0.055 | 0.258 | 0.255 | 0.228 | 0.229 | |

| Q3 | −0.078 | −0.073 | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.139 | 0.149 | 0.253 | 0.253 | 0.303 | 0.299 | |

| Q4 | 0.058 | 0.054 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.224 | 0.232 | 0.304 | 0.310 | 0.326 | 0.333 | |

| Q5 (highest) | −0.019 | −0.017 | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.126 | 0.140 | 0.255 | 0.258 | 0.259 | 0.270 | |

| US-born Black (non-Hispanic)a | |||||||||||

| Height (m) | Total | 0.278 | 0.277 | 0.307 | 0.304 | 0.235 | 0.236 | 0.170 | 0.169 | 0.174 | 0.174 |

| Income quintile | |||||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.201 | 0.196 | 0.088 | 0.081 | 0.219 | 0.219 | 0.145 | 0.144 | 0.172 | 0.173 | |

| Q2 | 0.402 | 0.396 | 0.306 | 0.301 | 0.247 | 0.248 | 0.186 | 0.182 | 0.153 | 0.149 | |

| Q3 | 0.364 | 0.370 | 0.424 | 0.427 | 0.242 | 0.242 | 0.237 | 0.236 | 0.175 | 0.174 | |

| Q4 | 0.662 | 0.653 | 0.720 | 0.707 | 0.415 | 0.417 | 0.227 | 0.222 | 0.281 | 0.281 | |

| Q5 (highest) | 0.555 | 0.578 | 0.687 | 0.701 | 0.293 | 0.298 | 0.279 | 0.283 | 0.232 | 0.234 | |

| Weight (kg) | Total | 0.157 | 0.123 | 0.097 | 0.089 | 0.244 | 0.249 | 0.317 | 0.331 | 0.317 | 0.330 |

| Income quintile | |||||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.273 | 0.228 | 0.034 | 0.019 | 0.256 | 0.269 | 0.344 | 0.370 | 0.326 | 0.345 | |

| Q2 | 0.083 | 0.094 | 0.074 | 0.055 | 0.237 | 0.237 | 0.315 | 0.325 | 0.324 | 0.331 | |

| Q3 | 0.650 | 0.629 | 0.586 | 0.552 | 0.434 | 0.443 | 0.438 | 0.480 | 0.431 | 0.469 | |

| Q4 | 0.533 | 0.423 | 0.179 | 0.185 | 0.294 | 0.278 | 0.367 | 0.352 | 0.338 | 0.332 | |

| Q5 (highest) | 0.199 | 0.210 | 0.185 | 0.213 | 0.309 | 0.338 | 0.362 | 0.393 | 0.342 | 0.367 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Total | 0.035 | −0.006 | −0.048 | −0.070 | 0.158 | 0.154 | 0.265 | 0.268 | 0.266 | 0.274 |

| Income quintile | |||||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.188 | 0.152 | −0.006 | −0.022 | 0.179 | 0.182 | 0.299 | 0.316 | 0.270 | 0.287 | |

| Q2 | −0.133 | −0.114 | −0.065 | −0.092 | 0.139 | 0.135 | 0.255 | 0.253 | 0.275 | 0.275 | |

| Q3 | 0.494 | 0.477 | 0.366 | 0.344 | 0.360 | 0.363 | 0.375 | 0.393 | 0.427 | 0.443 | |

| Q4 | 0.349 | 0.182 | −0.185 | −0.262 | 0.124 | 0.101 | 0.306 | 0.288 | 0.242 | 0.221 | |

| Q5 (highest) | −0.069 | −0.102 | −0.209 | −0.202 | 0.200 | 0.205 | 0.283 | 0.294 | 0.295 | 0.305 | |

Bold indicates a high haldane value of ≥0.3 and italic indicates an intermediate high haldane value of 0.2 – 0.3.

aSee definition of nativity-racial/ethnic groups in footnote to Table 1.

bThe haldane is denoted with subscripts, whereby p refers to phenotype, g refers to genotype and the N of generations is enclosed in parentheses,10 e.g. for an analysis of a change in phenotypic trait spanning 1.5 generations, the notation would be hp(1.5). The haldane values were calculated from weighted estimates of population means and population standard deviations (using NHES and NHANES analytic weights), with baseline set as NHES I.

Figure 1.

Haldane (log scale) vs generations elapsed (log scale) for height, weight and BMI, for (a) US-born White non-Hispanic population, and (b) US-born Black non-Hispanic population: US National Health Examination Survey (NHES) I (1959–1962; baseline) through US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2008

Height

High haldane values (≥0.3) occurred for height for NHANES I (1971–1975) and II (1976–1980) in virtually all income quintiles for both the US-born White and Black non-Hispanic populations, with values in excess of 0.5 observed only among the Black population. Thereafter, among the White population, the on-average haldane values were just below the intermediate high range (≥0.2 and <0.3), but were in this range in the lower income quintiles in NHANES III (1988–1994) and NHANES 2005–2008 and in the middle income quintiles in NHANES 1999–2004. Among the Black population, haldane values were in the intermediate high range overall and across income quintiles for NHANES III, but were so only in the upper income quintiles in NHANES 1999–2004 and 2005–2008.

Weight

Among both the White and Black populations, intermediate high haldane values became evident on-average and across income quintiles in NHANES III, and became high values in NHANES 1999–2004 and 2005–2008 (in the middle three income quintiles for the White population and in all income quintiles for the Black population). Among the Black population only, high values occurred for the middle income quintile in all surveys and also occurred in NHANES I for the second-highest income quintile and in NHANES IIII in the highest income quintile.

BMI

Among the White and Black populations, intermediate high haldane values occurred on-average and in all income quintiles starting with NHANES 1999–2004. High haldane values were evident among the Black population in all surveys for the middle income quintile and also occurred in NHANES 1999–2004 for the White and Black populations in the second-highest income quintile and in NHANES 2005–2008 for the White population in the second-highest income quintile.

Discussion

Our paper is, to our knowledge, the first in the public health literature to employ the haldane—a metric first developed by biologists to quantify the pace of evolutionary change9,10,15–17—to assess observed rates of phenotypic change (as opposed to projections18). Because the haldanes we have computed can be meaningfully compared with rates of phenotypic change as observed in other species, we are able to judge—in a way not feasible with conventional calculations of absolute differences and relative ratios over time—whether these rates of change are unusually large or not. Taken together, the results—based on US-born non-Hispanic White and Black adults ages 20–44—indicate that, for height, high rates of phenotypic change occurred chiefly between 1960 and 1980, especially for the Black population in the higher income quintiles. By contrast, for weight, high rates of phenotypic change became evident for both the White and the Black population in the late 1980s and increased thereafter; for BMI, the shift to high rates of change started in both groups in the late 1990s, especially in the middle-income quintiles.

As with any observational study evaluating haldanes, our investigation has several limitations. One is that, like most allochronic biological field studies (i.e. studies that ‘compare trait values for the same population at different points in time’10), our data pertained solely to phenotypic change and were available for only certain time points.10,16,17 Our study design was thus appropriate for evaluating the rapidity and magnitude of observed changes and was not intended to discern the mechanisms underlying these changes, e.g. involving phenotypic flexibility, selection, genetic drift or gene flow.9,10,13,15–18 Related use of repeat cross-sectional survey data additionally limited causal inference. Moreover, given the exploratory nature of our study, we did not attempt analysis of age-period-cohort effects25,26,45; this logical extension will be a focus of future work.

We also, like other field research using the haldane,10 assumed a constant generation length. Had we set generation length at 25 years, instead of our conservative choice of 20 years, the haldane values would have been 1.25 times larger, albeit leaving unchanged their rank order across income quintiles. Perhaps the most serious limitation is that our data spanned only 46 years, a time interval equivalent to 2.3 generations. By contrast, the typical number of generations reported in one analysis of microevolution across diverse species ranged from 10 to 30 generations, with the actual N ranging from 1 generation, in the case of Galapagos finches, to 140 generations, for the Hawaiian mosquitofish.10 Even if the estimates of haldanes based on <1 generation were unreliable, however, the findings based on 2.3 generations regarding high haldanes for weight and BMI, but not for height, would still hold.

Countering these limitations, we were able to employ rigorously measured (as opposed to self-report) anthropometric data obtained from large nationally representative samples of the US population, with analyses appropriately adjusting for survey design and sampling weights.27,28 Additionally, the socioeconomic measure we used—family income quintile—is one whose levels can (unlike for education) be meaningfully compared over time (as per the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) definition of poverty as below 50% of median household income).46–48

Further suggesting our data are credible is the magnitude of the haldanes we observed, with values corresponding to those reported in the published literature for changes in phenotypic traits in other species, including high values observed following rapid anthropogenic alterations to species’ ecological context.9,10,13,16,17 The biological field studies summarized in these articles likewise provide evidence of both rapid and reversible changes in phenotypic traits involving body size,9,10,13,16,17 leading to strong cautions against both interpolating and extrapolating haldane values.10 That the values we observed for height and weight are notably larger than those projected over 10 generations by the one other public health study to employ the haldane18 could potentially be due to differences involving: (1) study participants (nationally representative sample of the US population, diverse in its socioeconomic composition, vs the predominantly White middle-income Framingham cohort and its offspring49); (2) study design (repeat cross-sectional surveys vs a longitudinal cohort study and related offspring cohort study, enabling analyses to take into account genetic correlation); (3) number of generations at issue (our maximum of 2.3 vs a projection of 10, noting that haldane size tends to decrease with an increasing N of generations9,10,16,17); and (4) actual observed values (what we report) vs projections18 requiring the strong assumption that future conditions ‘continue to mirror the averages encountered by this population over the past 60 years’.18

Also germane, our results parallel those of other investigations documenting the late 20th century rapid rise of adult obesity in the US.22–26,41–44 The critical new contribution we make to this literature is that, via use of the haldane, our investigation employs a metric that offers new insight into just how rapid these shifts in body size are, as compared with usual rates of change observed in other species—and how similar they are to large shifts linked to rapid anthropogenic alterations of ecosystem conditions.10,16 Our results additionally underscore that post–1980 changes in weight, not height, are principally driving trends in BMI and its social distribution. This finding is consonant with research indicating that the rapid rise in global obesity is due to changes in societal exposures, not gene frequencies, with individuals’ socioeconomic trajectory from in utero up through post-pubertal attainment of adult stature influencing their early adult height, weight and BMI, and subsequent changes in their adult socioeconomic position also affecting their weight and BMI.21,22,50

Likely societal conditions driving these embodied changes, discussed at length elsewhere,22,24,51–53 pertain to systematic transformations, starting in the 1960s and escalating since the 1980s, in the US and global political economy of food production, marketing and consumption, resulting in dramatically increased consumption, in ever larger portions, of ‘cheap calories’, i.e. calorie-dense but low nutrient ‘junk food’ that is a highly profitable commodity for the food industry to sell, and one especially targeted at and consumed by persons who cannot afford higher-priced more nutritious and better quality food. Also likely contributing are changes since the 1960s in the political economy of work, resulting in increasingly sedentary jobs across all occupational classes and also greater use of cars (and less walking) to get to work, concomitant with persons with more vs fewer economic resources having greater options for leisure-time physical activity.54,55

In summary, by using the haldane—a metric designed to enable meaningful measurement and comparison, across species, of the rate of change of population characteristics—our study clarifies that observed recent US increases in weight and contingent increases in BMI are both large and rapid, at a pace well exceeding observed rates of changes in body size in other animal species living in their usual ecological context. Public health research and monitoring accordingly might consider using the haldane as a supplemental metric to place changes in population health and health inequities in a larger biological and historical context.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health [grant number 1 R21 HD060828-01A1 to N.K.]

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Morris J. Edinburgh: E & S Livingston; 1957. Uses of Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davey Smith G. Health Inequalities: Lifecourse Approaches. Bristol, UK: Policy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckfield J, Krieger N. Epi + demos + cracy: linking political systems and priorities to the magnitude of health inequities – evidence, gaps, and a research agenda. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:152–77. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People’s Health: Theory and Context. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krieger N, Rehkopf DH, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Marcelli E, Kennedy M. The fall and rise of US inequities in premature mortality: 1960–2002. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzati M, Friedman AB, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJ. The reversal of fortunes: trends in county mortality and cross-county mortality disparities in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e66. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050066. erratum PLoS Med 2008;5:e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: 2011. Measuring Progress. Available from: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/implementing/MeasuringProgress.pdf (8 September 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper S, Lynch J. Methods for Measuring Cancer Disparities: Using Data Relevant to Healthy People 2010 Cancer-Related Objectives. NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series, Number 6. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2005. NIH Publication No. 05–5777. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gingerich PD. Quantification and comparison of evolutionary rates. Am J Sci. 1993;293A:453–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendry AP, Kinnison MT. The pace of modern life: measuring rates of contemporary microevolution. Evolution. 1999;53:1637–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quirke VM Haldane, John Burdon Sanderson. (1892–1964). In Colin Matthew (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Available from: http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33641 (8 September 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werskey G. The Marxist critique of capitalist science: a history in three movements? Science as Culture. 2007;16:397–461. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piersma T, van Gils JA. The Flexible Phenotype: A Body-Centred Integration of Ecology, Physiology, and Behaviour. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev. 2007;82:591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldane JBS. Suggestions as to quantitative measurement of rates of evolution. Evolution. 1949;3:51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1949.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendry AP, Farrugia TJ, Kinnison MT. Human influences on rates of phenotypic change in wild animal populations. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gingerich PD. Rates of evolution. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2009;40:657–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byars SG, Ewbank D, Govindaraju DR, Stearns SC. Natural selection in a contemporary human population. PNAS. 2010;107(Suppl 1):1787–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906199106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:887–903. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:668–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger N, Davey Smith G. Bodies count and body counts: social epidemiology and embodying inequality. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:92–103. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity epidemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378:804–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States – gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmerman FJ. Using marketing muscle to sell fat: the rise of obesity in the modern economy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090810-182502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ljungvall Å, Zimmerman FJ. Bigger bodies: long-term trends and disparities in obesity and body-mass index among U.S. adults, 1960–2008. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:109–19. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komlos J, Lauderdale BE. Underperformance in affluence: the remarkable relative decline in U.S. heights in the second half of the 20th century. Soc Sci Q. 2007;88:283–305. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. NHES I-III Data Files. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/cyclei_iii.htm (8 September 2012, date last accessed)

- 28.National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm (8 September 2012, date last accessed)

- 29.Williamson DF. Descriptive epidemiology of body weight and weight change in U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:646–49. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson C, Jun K. Historical census statistics on the foreign-born population of the United States: 1850–2000. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Working Paper No. 81. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2006. Available from: http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0081/twps0081.html (8 September 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldin C, Katz LF. The race between education and technology: the evolution of U.S. educational wage differentials, 1890 to 2005. NBER Working Paper 12984, March 2007. http://www.nber.org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/papers/w12984.pdf (8 September 2012, date last accessed)

- 32.Kane TJ, Rouse CE. Labor-market returns to two and four year college. Am Econ Rev. 1995;86:600–14. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber TP, Cheung SY. Horizontal stratification in postsecondary education: forms, explanations, and implications. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:299–318. [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Census Bureau. Income data, historical tables, family income. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/families/ (8 September 2012, date last accessed)

- 35.Heck KE, Schoendorf KC, Ventura SJ, Kiely JL. Delayed childbearing by education level in the United States, 1969–1994. Matern Child Health J. 1997;1:81–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1026218322723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ. Fertility and abortion rates in the United States, 1960–2002. Int J Andrology. 2006;29:34–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Delayed childbearing: More women are having their first child later in life. NCHS data brief, no 21. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db21.pdf (8 September 2012, date last accessed) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SAS/STAT(R) 9.2 User’s Guide, 2nd edn. http://www.sas.com/index.html (8 September 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flegal KM, Harlan WR, Landis JR. Secular trends in body mass index and skinfold thickness with socioeconomic factors in young adult men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;48:544–51. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flegal KM, Harlan WR, Landis JR. Secular trends in body mass index and skinfold thickness with socioeconomic factors in young adult women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;48:535–43. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flegal KM, Caroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics, no. 347. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad347.pdf (8 September 2012, date last accessed) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2007–2008. NHANES Health E-Stat, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf (8 September 2012, date last accessed)

- 44.Hu FB. Descriptive epidemiology of obesity trends. In: Hu FB, editor. Obesity Epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holford TR. Temporal factors in public health surveillance: sorting out age, period, and cohort effects. In: Brookmehyer R, Stroup DF, editors. Monitoring the Health of Populations: Statistical Principles and Methods for Public Health Surveillance. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brady D. Rethinking the sociological measure of poverty. Social Forces. 2003;81:715–51. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Society at a glance 2011 – OECD social indicators. http://www.oecd.org/social/socialpoliciesanddata/societyataglance2011-oecdsocialindicators.htm (27 November 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Agostino RB, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P for the CHD Risk Prediction Group. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynch J, Davey Smith G. A lifecourse approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tillotson JE. America’s obesity: conflicting public policies, industrial economic development, and unintended human consequences. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:617–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludwig DS, Nestle M. Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA. 2008;300:1808–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grier SA, Kumanyika SK. The context for choice: health implications of targeted food and beverage marketing to African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1616–29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brownson R, Boehmer TK, Luke DA. Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors? Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:421–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Trends in over 5 decades in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]