Abstract

Objectives

To assess the relationship of left atrial (LA) phasic volumes and LA reservoir function with subclinical cerebrovascular disease in a stroke-free community-based cohort.

Background

An increase in LA size is associated with cardiovascular events including stroke. However, it is not known whether LA phasic volumes and reservoir function are associated with subclinical cerebrovascular disease.

Methods

LA minimum (LAVmin) and maximum (LAVmax) volumes, and LA reservoir function, measured as total emptying volume (LAEV) and total emptying fraction (LAEF), were assessed by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography in 455 stroke-free participants from the community-based Cardiovascular Abnormalities and Brain Lesions (CABL) study. Subclinical cerebrovascular disease was assessed as silent brain infarcts (SBI) and white matter hyperintensity volume (WMHV) by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Results

SBI prevalence was 15.4%; mean WMHV was 0.66±0.92%. Participants with SBI showed greater LAVmin (17.1±9.3 vs. 12.5±5.6 ml/m2, p<0.01) and LAVmax (26.6±8.8 vs. 23.3±7.0 ml/m2, p<0.01) compared to those without SBI. LAEV (9.5±3.4 vs. 10.8±3.9 ml/m2, p<0.01) and LAEF (38.7±14.7% vs. 47.0±11.9%, p<0.01) were also reduced in participants with SBI. In univariate analyses, greater LA volumes and smaller reservoir function were significantly associated with greater WMHV. In multivariate analyses, LAVmin remained significantly associated with SBI [adjusted odds ratio (OR) per SD increase: 1.37, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.04–1.80, p<0.05] and with WMHV (β=0.12, p<0.01), whereas LAVmax was not independently associated with either. Smaller LAEF was independently associated with SBI (adjusted OR=0.67, 95% CI 0.50–0.90, p<0.01) and WMHV (β=−0.09, p<0.05).

Conclusions

Greater LA volumes and reduced LA reservoir function are associated with subclinical cerebrovascular disease detected by brain MRI in subjects without history of stroke. LAVmin and LAEF, in particular, are more strongly associated with SBI and WMHV than the more commonly measured LAVmax, and their relationship with subclinical brain lesions is independent of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Keywords: Left atrial volume, Silent brain infarct, White matter hyperintensity volume, Magnetic resonance imaging, Three-dimensional echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the prevalence of stroke in the population over 20 years of age is estimated at 3.0%, with 7,000,000 people having suffered a stroke at some point in their lifetime (1). Brain imaging studies have revealed that the prevalence of asymptomatic brain vascular lesions is substantially higher than clinically overt disease. In the general population, the prevalence of silent brain infarcts (SBI) has been estimated from 7% to 28%, with a steep increase observed with aging (2–8). Cerebral white matter hyperintensities, often expressed as percent of the brain volume (WMHV), have also been described in asymptomatic participants in population studies (9–12). Both SBI and WMHV have been associated with future incidence of stroke, cognitive impairment, and dementia (10,11,13–15).

Increased left atrial (LA) size is associated with higher mortality and cardiovascular events including stroke (16–18). Among measures of LA size, LA volume appears to provide the best prediction of adverse prognosis (19). LA volume is usually measured in end-systole, when the LA reaches maximum expansion (LAVmax). Growing evidence, however, suggests that the analysis of LA volume in different phases of the cardiac cycle may provide additional prognostic information. In particular, the LA minimum (end-diastolic) volume (LAVmin) and the LA reservoir function are better predictors of incident atrial arrhythmias than LAVmax (20,21). However, it is not known whether and to what extent parameters of LA size and function are associated with subclinical cerebrovascular disease. The identification of markers of cerebrovascular disease at an early subclinical stage might improve risk stratification of people at high cardiovascular risk, and allow the use of more aggressive therapeutic strategies to reduce their risk. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationships of LA volumes and reservoir function measured by real-time three-dimensional (RT3D) echocardiography with the presence of subclinical cerebrovascular disease evaluated by MRI in a community-based cohort.

METHODS

Study population

The Cardiovascular Abnormalities and Brain Lesions (CABL) study is a community-based epidemiologic study designed to investigate the cardiovascular predictors of silent cerebrovascular disease in the community. CABL based its recruitment on the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS), a population-based prospective study that enrolled 3,298 participants from the community living in northern Manhattan between 1993 and 2001. The study design and recruitment details of NOMAS have been described previously (22). Participants were invited to participate in an MRI substudy beginning in 2003 and were eligible for the MRI cohort if they: 1) were at least 55 years of age; 2) had no contraindications to MRI; and 3) did not have a prior diagnosis of stroke. From September 2005 to July 2010, NOMAS MRI participants that voluntarily agreed to undergo a more extensive cardiovascular evaluation were included in CABL. Participants for whom LA volume measurements by RT3D echocardiography and brain MRI information were available constitute the final sample of the present study. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University Medical Center and of University of Miami.

Risk factors assessment

Cardiovascular risk factors were ascertained through direct examination and interview by trained research assistants. Systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured at the non-dominant arm in sitting position after 5 minutes of rest using a mercury sphygmomanometer and a proportioned arm cuff. Study participants were not asked to discontinue anti-hypertensive medications on the day of the visit. Two blood pressure measurements were performed and averaged. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg at the time of the visit (mean of two readings), or patient’s self-reported history of hypertension or of anti-hypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL or patient’s self-reported history of diabetes or of diabetes medications. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total serum cholesterol >240 mg/dL, a patient’s self-report of hypercholesterolemia or of use of lipid-lowering treatment. Coronary artery disease (CAD) was defined as a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention, typical angina or use of anti-ischemic medications. Cigarette smoking habit, either at time of the interview or in the past, was recorded. Atrial fibrillation was defined from ECG at the time of echocardiography or from self-reported history. Race-ethnicity was based on self-identification modeled after the U.S. census.

Echocardiographic assessment

Two-dimensional echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a commercially available system (iE 33, Philips, Andover, MA) by a trained, registered cardiac sonographer according to a standardized protocol. LV end-diastolic diameter, indexed by body surface area (LVEDi), inter-ventricular septum thickness, and posterior wall thickness were measured from a parasternal long-axis view according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography (23). LV ejection fraction was calculated using the biplane modified Simpson’s rule, replaced by semi-quantitative method or visual estimation in case of technically suboptimal images. LV mass was calculated with a validated method (24) and indexed by body surface area. LV relative wall thickness was calculated as: 2 × posterior wall thickness / LV end-diastolic diameter. LV diastolic function assessment has been previously described in detail (25). Briefly, color Doppler imaging was used to visualize the trans-mitral flow from an apical 4-chamber view; the pulsed-wave Doppler sample volume was placed perpendicular to the inflow jet at the level of mitral valve leaflet tips. The peak early velocity (E), late velocity (A), and deceleration time (DT) of the mitral inflow were measured, and the E/A ratio was calculated. Mitral annular velocities were evaluated by pulsed-wave tissue- Doppler imaging (TDI) and sampled on the longitudinal axis from the apical 4-chamber view. The peak early diastolic velocity (e’) of the lateral and the septal mitral annulus were measured and the average value was calculated. Diastolic dysfunction was defined as: E/A ≤ 0.7 or DT>260 ms; or E/A between 0.7–1.5 and e’ < 7 cm/s; or E/A > 1.5 and e’ < 7 cm/s or DT<140 ms.

Real-time three-dimensional echocardiography

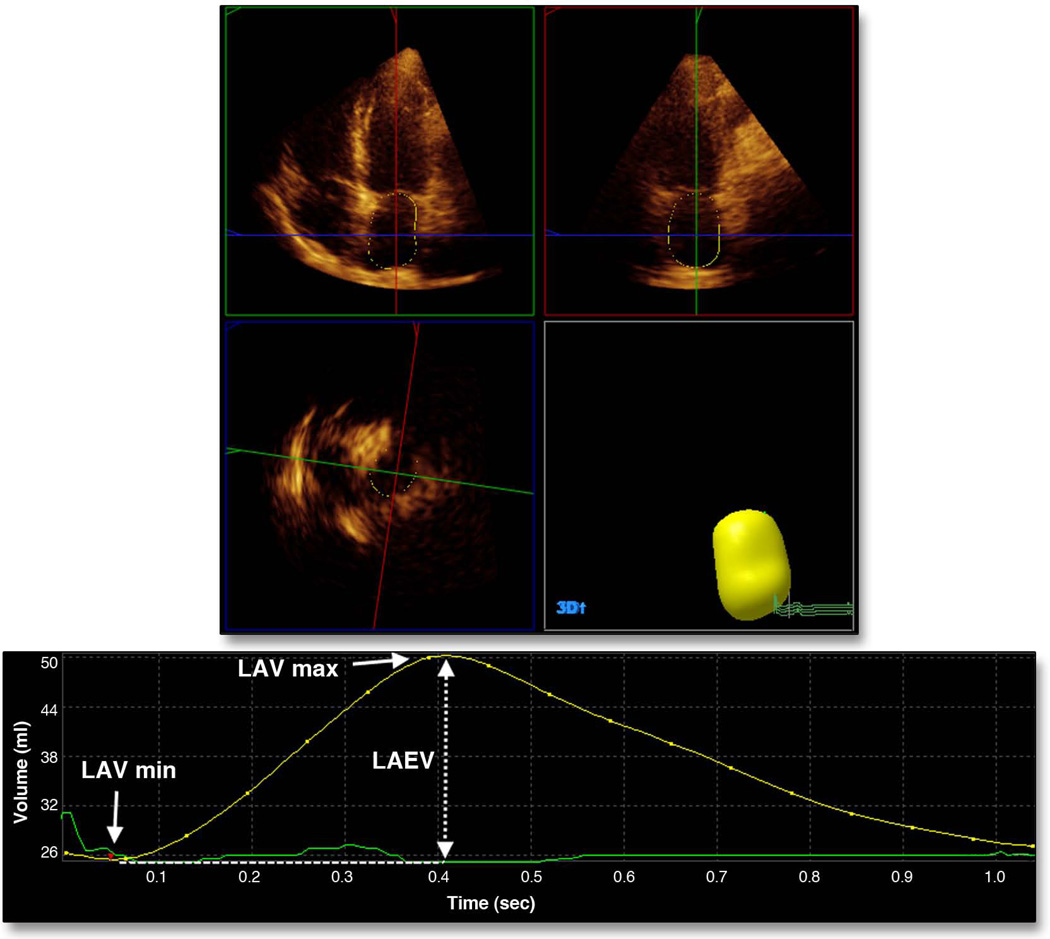

RT3D imaging was performed using a commercially available ultrasound machine (iE33, Philips, Andover, MA) equipped with an X3-1 matrix array transducer. A pyramidal full volume dataset was obtained from the acquisition of 4 sub-volumes from 4 consecutive cardiac cycles triggered to the R wave of the ECG. Sector dimensions and depth were set to include the whole left ventricle and the left atrium, allowing volume rates between 15 and 25 per second. Measurement of LA volumes was performed offline using commercially available software (QLAB Advanced Quantification software, version 8.1, Philips) by a single reader blinded to the study participants’ clinical characteristics. A detailed description of the technique has been reported previously (26,27). Briefly, five anatomical landmarks (septal, lateral, anterior and inferior mitral annulus, and posterior wall of the LA) were manually identified by the operator, semi-automated border detection was performed by the software, and LA borders were tracked throughout the entire cardiac cycle (Figure 1). Manual correction on all possible 3D planes was performed by the reader in case of inaccurate endocardial detection. LA volume measurements were indexed by the body surface area. The parameters of LA size and function included in our analyses were:

-

-

LA minimum volume (LAVmin): LA end-diastolic volume measured at the first frame after mitral valve closure;

-

-

LA maximum volume (LAVmax): LA end-systolic volume measured one frame before mitral valve opening;

-

-

LA total emptying volume (LAEV): LAVmax − LAVmin, a measure of absolute LA reservoir function;

LA total emptying fraction (LAEF): 100 × (LAVmax − LAVmin)/LAVmax, a measure of relative LA reservoir function.

Figure 1. Left atrial volumes by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography.

Measurement of LAVmax and LAVmin. LA reservoir function was calculated as LA total emptying volume (LAEV = LAVmax − LAVmin) and as LA total emptying fraction (100 × LAEV/LAVmax).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

A detailed description of the assessment of subclinical cerebrovascular lesions has been published previously (3,9). Briefly, brain imaging was performed on a 1.5-T MRI system (Philips Medical Systems). Median time between MRI and echocardiographic examination was 2 days (75th percentile: 5 days). SBI were rated by two of the authors (C.D. and M.Y.) and defined as either a cavitation on the fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence of at least 3 mm in size, distinct from a vessel (due to the lack of signal void on T2 sequence), and of equal intensity to cerebrospinal fluid in the case of lacunar infarction or as a wedge shaped cortical or cerebellar area of encephalomalacia with surrounding gliosis consistent with infarction due to distal arterial branch occlusion. Inter-observer agreement for SBI detection was 93.3% (3). WMHV analysis was based on a FLAIR (Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery) image and performed using the Quantum 6.2 package on a Sun Microsystems Ultra 5 workstation. WMHV was expressed as proportion of total cranial volume to correct for differences in head size, and log-transformed (log-WMHV) to achieve a normal distribution for analysis as a continuous variable. Examples of different forms of subclinical ischemic lesions are shown in Figure 2. All measurements were performed blinded to participant identifying and clinical information.

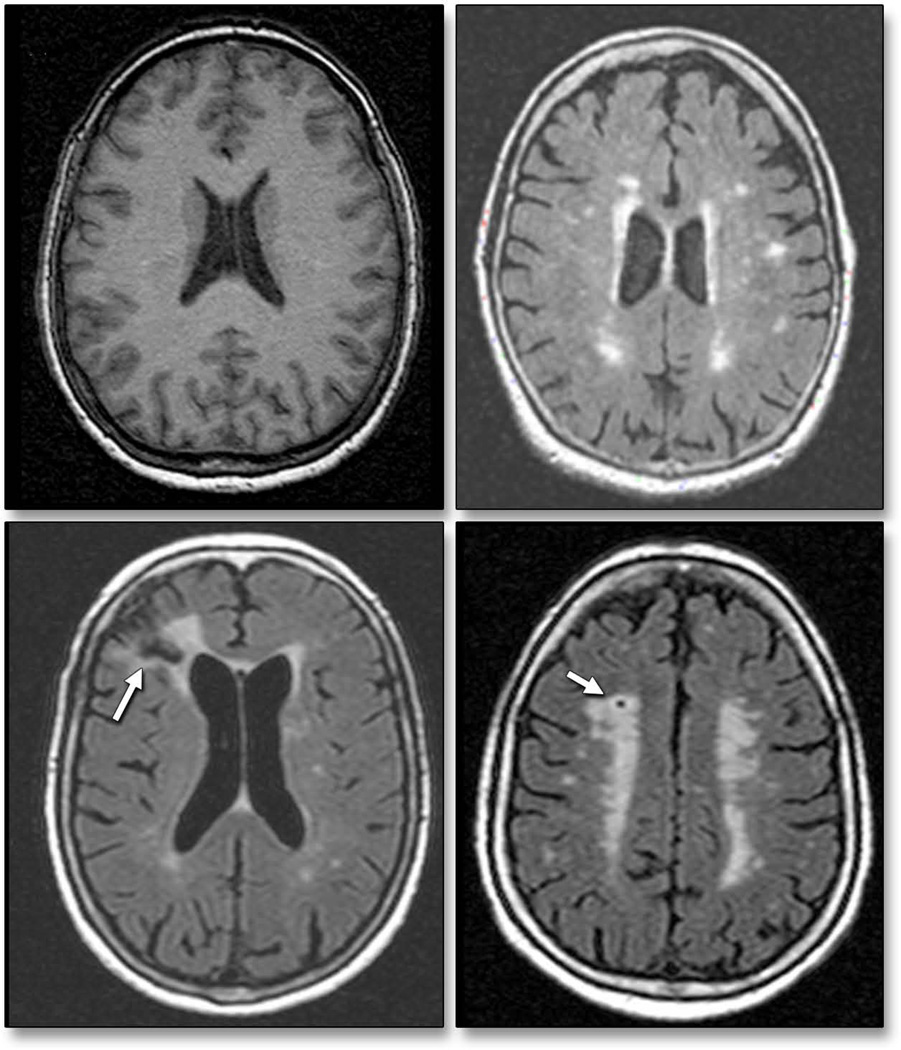

Figure 2. Subclinical brain lesions by magnetic resonance imaging.

Representative axial MRI slices from study participants showing normal brain (top left panel) and subclinical ischemic changes, including white matter hyperintensities (top right panel), cortical infarction (bottom left panel), and lacunar infarction (bottom right panel).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as proportions for categorical variables. Differences between groups were assessed by Student’s ttest and by Pearson Chi-Square. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) and paired t-tests were used to assess reproducibility of echocardiographic measurements. Logistic regression models were used for the analysis of risk factors of SBI, and parameter estimates (B), odds ratios (OR) per standard deviation change and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. The association of log-WMHV with demographics, clinical factors and LA parameters was assessed by linear regression models. The predictors and the outcome variables were standardized with corresponding standard deviations and both unstandardized (B) and standardized (β) parameter estimates and relative standard errors (SE) were reported. Two multivariate models were built to test the relationship between LA volumes and SBI/WMHV. The first model was adjusted for age, sex, race-ethnicity and BMI. For the second model, covariates with a p<0.2 for subclinical cerebrovascular disease in univariate analysis were entered in a stepwise fashion with entry and removal criteria set at p values of 0.2 and 0.3 respectively. For all statistical analyses, a 2-tailed p<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Reproducibility of LA volumes

Reproducibility of LA volume measurements was assessed in 15 randomly selected subjects. LAVmin and LAVmax were re-measured by the original reader and by a second reader experienced in 3D echocardiography in a blinded fashion. Intra-observer ICC were 0.96 for LAVmin [95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.88–0.99] and 0.94 for LAVmax (95% CI: 0.85–0.98). The mean difference between two measurements was 0.13±1.79 ml/m2 for LAVmin (p=0.78) and 0.42±2.29 ml/m2 for LAVmax (p=0.49). Inter-observer ICC were 0.94 for LAVmin (95% CI: 0.85–0.98) and 0.95 for LAVmax (95% CI: 0.86–0.98). The mean difference between two measurements was 0.44±2.27 ml/m2 for LAVmin (p=0.46) and 0.52±2.56 ml/m2 for LAVmax (p=0.45).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

For the present analysis, three-dimensional analysis of LA volumes and function was performed in 500 subjects. Image quality was suboptimal for accurate analysis in 45 (9%), leading to the final study sample of 455. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Mean age of the 455 study participants was 70.2±10.1 years, mean BMI was 27.7±4.7, and 278 (61.1%) were women. Presence of SBI was detected by MRI in 70 of the 455 participants (15.4%); in 10 cases (14.3%), the SBI were located in cortical areas and 60 (85.7%) were subcortical. Mean WMHV was 0.66±0.92% (median 0.31%, min 0%, max 5.7%). Prevalence of hypertension was 75.8%, mean SBP was 134.7±17.6 mmHg and mean DBP was 77.9±9.5 mmHg. Echocardiographic data for the study population are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

| N=455 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 70.2±10.1 |

| Women, n (%) | 278 (61.1) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.7±4.7 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 134.7±17.6 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 77.9±9.5 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 345 (75.8) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 125 (27.5) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 289 (63.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 25 (5.5) |

| CAD, n (%) | 28 (6.2) |

| History of cigarette smoking, n (%) | 244 (53.6) |

| Race-ethnicity | |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 62 (13.6) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 314 (69.0) |

| African-American, n (%) | 71 (15.6) |

| Other, n (%) | 8 (1.8) |

BMI: Body mass index. BP: Blood pressure. CAD: Coronary artery disease

Table 2.

Two- and three-dimensional echocardiographic data of the study population

| Two-dimensional echocardiography | |

|---|---|

| LV septal thickness, mm | 11.4±1.9 |

| LVEDi, mm/m2 | 26.0±3.2 |

| LV posterior wall thickness, mm | 11.1±1.7 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 106.3±27.3 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.49±0.09 |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 62.4±8.0 |

| Diastolic dysfunction, n (%) | 247 (54.3) |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 69.6±11.1 |

| Mitral regurgitation > mild, n (%) | 39 (8.6) |

| Three-dimensional echocardiography | |

| LAVmax, ml/m2 | 23.8±7.4 |

| LAVmin, ml/m2 | 13.2±6.5 |

| LAEV, ml/m2 | 10.6±3.8 |

| LAEF, % | 45.7±12.7 |

LVEDi: LV end-diastolic diameter index. LAVmax: Left atrial maximum volume. LAVmin: Left atrial minimum volume. LAEV: Left atrial total emptying volume. LAEF: Left atrial total emptying fraction.

Cardiovascular risk factors and LA volumes

Hypertension was significantly associated with LAVmax (r=0.13, p<0.01), LAVmin (r=0.18, p<0.01) and LAEF (r=−0.18, p<0.01), but not with LAEV (r=−0.06, p=0.21). Similarly, SBP was significantly associated with LAVmax (r=0.10, p<0.05), LAVmin (r=0.15, p<0.01) and LAEF (r=−0.19, p<0.01). Diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, cigarette smoking, and history of CAD did not show significant association with LA volumes and function parameters.

Univariate correlates of subclinical cerebrovascular disease

The relationships of demographic and clinical characteristics with SBI and WMHV are shown in Table 3. Presence of SBI was significantly associated with older age (p<0.01), hypertension (p<0.05), diabetes (p=0.05), history of atrial fibrillation (p<0.01), LV mass (p<0.01), and more than mild mitral regurgitation (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Univariate correlates of subclinical cerebrovascular disease

| SBI | Log-WMHV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | P value | B (SE) | P value | |

| Age | 0.06 (0.01) | <0.01 | 4.7 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| Male sex | −0.2 (0.3) | 0.46 | 0.9 (9.3) | 0.92 |

| BMI | −0.02 (0.03) | 0.47 | −3.4 (1.0) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 0.9 (0.4) | <0.05 | 43.0 (10.4) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.05 | −3.3 (10.1) | 0.75 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | −0.03 (0.27) | 0.90 | −9.9 (9.4) | 0.29 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.6 (0.4) | <0.01 | 64.6 (20.0) | <0.01 |

| CAD | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.15 | 38.7 (18.7) | <0.05 |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.70 | 10.3 (9.1) | 0.26 |

| LV mass | 0.02 (0.004) | <0.01 | 0.8 (0.2) | <0.01 |

| Relative wall thickness | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.07 | 248.1 (48.9) | <0.01 |

| LV ejection fraction | −0.03 (0.01) | 0.07 | −0.9 (0.6) | 0.12 |

| LV diastolic dysfunction | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.07 | 43.6 (8.9) | <0.01 |

| MV regurgitation (> mild) | 0.9 (0.4) | <0.05 | 11.3 (16.2) | 0.48 |

| Heart rate | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.22 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.56 |

Values in table are parameter estimates (B) and relative standard error (SE). SBI: Silent brain infarcts. WMHV: White matter hyperintensities volume. BMI: Body mass index. CAD: Coronary artery disease. MV: Mitral valve.

WMHV was significantly associated with age, BMI, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, LV mass, relative wall thickness, LV diastolic dysfunction (all p<0.01), and CAD (p<0.05).

LA volumes and reservoir function and subclinical cerebrovascular disease

Participants with SBI had greater LAVmin (17.1±9.3 ml/m2 vs. 12.5±5.6 ml/m2, p<0.01) and greater LAVmax (26.6±8.8 ml/m2 vs. 23.3±7.0 ml/m2, p=0.01) compared to those without SBI. LAEV (9.5±3.4 ml/m2 vs. 10.8±3.9 ml/m2, p<0.01) and LAEF (38.7±14.7% vs. 47.0±11.9%, p<0.01) were significantly reduced in participants with SBI compared to those without SBI.

The association of LA volumes and function with SBI is shown in Table 4. In unadjusted analysis, both LAVmax (OR per SD increase=1.46, 95% CI 1.15–1.85) and LAVmin (OR=1.72, 95% CI 1.37–2.16) were associated with SBI. LAVmin remained significantly associated with SBI in multivariate models after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and race-ethnicity (OR=1.47, 95% CI 1.16–1.86) and in a model further adjusted for other cardiovascular risk factors and confounders (OR=1.37, 95% CI 1.04–1.80). A LAVmin > 15.1 ml/m2 (75th percentile of the distribution) was independently associated with a significantly increased risk of SBI (adjusted OR=2.56, 95% CI 1.36–4.84). LAVmax lost its significant association with SBI in multivariate models. In models including both LA volumes, LAVmin was still significantly associated with SBI (adjusted OR=2.26, 95%CI 1.34–3.83), whereas LAVmax was not. A reduction in LA reservoir function (LAEV and LAEF) was significantly associated with SBI in univariate analyses; in multivariate models, a smaller LAEF remained significantly associated with SBI (adjusted OR per standard deviation increase=0.67, 95% CI 0.50–0.90). A LAEF < 37.7 % (25th percentile of the distribution) was independently associated with a significantly increased risk of SBI (adjusted OR=2.41, 95% CI 1.31–4.41).

Table 4.

Association of LA volumes and reservoir function with the presence of SBI

| Independent variable |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted† OR (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAVmax | 1.46 (1.15–1.85) | <0.01 | 1.26 (0.99–1.60) | 0.06 | 1.15 (0.88–1.50) | 0.32 |

| LAVmin | 1.72 (1.37–2.16) | <0.01 | 1.47 (1.16–1.86) | <0.01 | 1.37 (1.04–1.80) | <0.05 |

| LAEV | 0.68 (0.51–0.90) | <0.01 | 0.73 (0.55–0.97) | <0.05 | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) | 0.07 |

| LAEF | 0.53 (0.41–0.69) | <0.01 | 0.63 (0.48–0.83) | <0.01 | 0.67 (0.50–0.90) | <0.01 |

Values in table are odds ratios (OR) per standard deviation increase and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

adjusted for age, sex, BMI and race-ethnicity

stepwise model (covariates: age, hypertension, diabetes, CAD, atrial fibrillation, LV mass, relative wall thickness, LV ejection fraction, LV diastolic dysfunction, and mitral regurgitation). LAVmax: Left atrial maximum volume. LAVmin: Left atrial minimum volume. LAEV: Left atrial total emptying volume. LAEF: Left atrial total emptying fraction.

Similar results were observed for the association between LA volumes and WMHV (Table 5). In univariate analyses, LA volumes and LA reservoir function parameters were all significantly associated with WMHV. In multivariate analyses, however, only LAVmin (β=0.12, p<0.01) and LAEF (β=−0.09, p<0.05) showed a significant association with WMHV. LAVmin remained independently associated with WMHV even when both LA volumes were included in the same model (β=0.18, p<0.05).

Table 5.

Association of LA volumes and reservoir function with log-WMHV.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable |

B (SE) | β | P value | B (SE) | β | P value | B (SE) | β | P value |

| LAVmax | 2.6 (0.6) | 0.19 | <0.01 | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| LAVmin | 4.2 (0.7) | 0.29 | <0.01 | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.11 | <0.05 | 1.8 (0.7) | 0.12 | <0.01 |

| LAEV | −2.7 (1.2) | −0.11 | <0.05 | −1.4 (1.1) | −0.06 | 0.19 | −1.3 (1.0) | −0.05 | 0.21 |

| LAEF | −2.1 (0.3) | −0.27 | <0.01 | −0.8 (0.3) | −0.11 | <0.05 | −0.7 (0.3) | −0.09 | <0.05 |

Values in table are parameter estimates (B) with relative standard error (SE), and standardized parameter estimates (β).

adjusted for age, sex, BMI and race-ethnicity.

stepwise model (covariates: age, BMI, hypertension, CAD, atrial fibrillation, LV mass, relative wall thickness, LV ejection fraction, and LV diastolic dysfunction). LAVmax: Left atrial maximum volume. LAVmin: Left atrial minimum volume. LAEV: Left atrial total emptying volume. LAEF: Left atrial total emptying fraction.

In a sub-analysis excluding subjects with atrial fibrillation and significant mitral regurgitation, LAVmin confirmed its independent association with SBI (adjusted OR=1.69, 95% CI 1.09–2.64) and with WMHV (β=0.10, p<0.05), whereas LAVmax did not show significant associations with either SBI (adjusted OR=1.29, 95% CI 0.87–1.92) or WMHV (β=0.07, p=0.12).

DISCUSSION

The present study investigates for the first time the relationship of LA volumes and reservoir function with subclinical cerebrovascular disease. We demonstrated that greater LA volumes and smaller LA reservoir function are associated with SBI and WMHV. In addition, we showed that LAVmin is a stronger predictor of silent cerebrovascular lesions than the commonly used LAVmax, and that its significant association with subclinical brain disease persisted after controlling for potential confounders and risk factors.

The mechanisms linking an increase in LA volume with cerebrovascular disease are not completely understood, but it is reasonable to hypothesize that the mechanisms suggested for the relationship between LA size and stroke may at least in part apply to silent cerebrovascular disease as well. This is biologically plausible considering that 1) subjects with subclinical brain lesions are more likely to experience an overt cerebrovascular event, and 2) subclinical and overt cerebrovascular disease share several common determinants and risk factors (28), and may therefore share some of their causal factors. An enlarged LA can be an expression of hypertension, LV hypertrophy, LV diastolic dysfunction and increased filling pressure, and is therefore considered a powerful marker of cardiovascular risk (29). The relationship of LA size with the aforementioned cardiovascular risk factors, which are in turn associated with atherosclerotic disease, may represent a link between the enlargement of the left atrium and the presence of silent cerebrovascular lesions. Although the etiology of silent cerebral disease is not completely understood, arteriosclerotic disease of small penetrating vessels often appears to be its likely cause. In pathological and clinical studies, SBI frequently showed the characteristics of lacunes (30), and WMHV were characterized by demyelination and gliosis, presumably from chronic hypoperfusion of the white matter (31,32). Several studies have documented the association of silent cerebrovascular lesions with established risk factors for arterial atherosclerosis such as hypertension (4,33), LV hypertrophy (34), smoking (35), and hyperhomocysteinemia (9,36). WMHV have also been shown to be associated with aortic and carotid atherosclerosis and intima-medial thickness (37,38). In this view of shared underlying mechanisms leading to cardiac and cerebral abnormalities, the left atrium can be considered a strategic component, whose dimension and function reflect a variety of age- and risk factors-associated changes that also portend the development of cerebral microvascular perfusion defects and the resulting subclinical brain disease.

Another possible mechanism linking increased LA volume and brain lesions is cardioembolism. An increased LA size is strongly associated with incident atrial fibrillation and with a higher prevalence of undetected episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (39,40). Atrial fibrillation favors blood stasis and thrombus formation in the LA appendage, which can lead to cerebral embolism. In our study, atrial fibrillation was associated with SBI and WMHV, and may have been involved in the association of LA volumes with cerebral lesions. Our findings, however, remained unchanged after controlling for the presence of atrial fibrillation in multivariate models, and even when participants with atrial fibrillation (and also mitral regurgitation, a condition directly causative of LA enlargement) were excluded from the analysis. It is possible, however, that undetected asymptomatic episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in participants with higher LA volume may have caused cardioembolism that contributed to our findings. The same consideration applies to participants with lower LA reservoir function, which has also been found to be a potent predictor of atrial arrhythmias (41). However, the number of cortical brain infarcts, generally considered to be of more likely cardioembolic origin, was too low (N=10) to perform a separate analysis by type, which might have strengthened the hypothesis of cardioembolism as a cause for the association between LA volumes and SBIs.

So far, the great majority of studies documenting the prognostic value of LA size considered LAVmax as an indicator of risk. LAVmax, however, represents the LA volume at the end of LV systolic contraction, and it is therefore influenced by the systolic function of the ventricle. LAVmin, on the other hand, is measured at end-diastole, when the LA is directly exposed to the LV pressure. LAVmin may be better correlated to LV diastolic function and reflect the chronic LV pressure elevation more accurately than LAVmax (42); furthermore, LA reservoir function, besides being negatively affected by LV diastolic dysfunction, is also sensitive to alterations in LV systolic function (43), and therefore might represent an integrated marker of risk. Recently, we demonstrated that LAVmin is indeed a better correlate of LV diastolic function than LAVmax, and that the LA reservoir function is strongly affected by the LV longitudinal systolic function (27); therefore we hypothesized that the weaker relationship of LAVmax with LV diastolic function may be in part due to the confounding action of the LV systolic function, which can be different among individuals with similar LV filling pressures, and therefore reduce the fit of the relationship LA end-systolic volume – LV diastolic function. In line with these considerations, other studies demonstrated that LAVmin and LA reservoir function are stronger predictors of events and atrial arrhythmias than LAVmax, further confirming that LAVmin might be a better indicator of LA remodeling and a better predictor of cardiovascular risk (21,44). Our findings are in line with these studies, and add novel evidence indicating that LAVmin and LA reservoir function are also strong and independent predictors of subclinical cerebrovascular disease.

Our study has potential clinical implications. It is known that SBI and WMHV are associated with future development of stroke, cognitive impairment, and dementia. In addition to the already known association of SBI and WMHV with cardiovascular risk factors, our study adds LA volume, LAVmin in particular, and LA reservoir function to the correlates of subclinical cerebrovascular disease. A more aggressive clinical management of subjects with risk factors and with increased LA volume or reduced LA reservoir function might therefore be potentially helpful in reducing future clinical manifestations of cerebrovascular disease, although further studies are required to confirm this approach. The assessment of LA phasic volumes is not part of standard clinical practice. The demonstration that LAVmin and LAEF are better predictors of subclinical cerebrovascular disease than the commonly utilized LAVmax adds to existing evidence in favor of adopting a more comprehensive assessment of LA mechanics, which might allow early identification of subjects with subclinical signs of cerebral disease and refine risk stratification. Although two-dimensional echocardiography can provide accurate assessment of LA volume and function and is still the method of choice for many laboratories, modern real-time three-dimensional echocardiography, with its semi-automated endocardial border detection algorithms, allows easy and fast evaluation of LA mechanics and, after adequate operator training, can provide reproducible data with an acceptable offline analysis time (45). In particular, the intra- and inter-observer reproducibility of LAVmin in our study was excellent and comparable to that of LAVmax, therefore we do not confirm the finding of lower reproducibility of LAVmin observed in a previous study (21).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include the relatively large number of subjects studied with advanced imaging techniques (RT3D echocardiography and brain MRI), the low risk of selection bias (the study sample was drawn from a community-cohort study that employed random selection of participants), the wide range of cardiovascular risk profiles present in our study population, and the confirmation of our findings after adjustment for appropriate covariates. However, our study also has limitations. Since the study population included subjects over age 50, our results may not apply to younger populations. However, silent brain disease is more commonly found in the elderly, which made our study cohort an ideal setting for this study. Our study population had high frequency of cardiovascular risk factors and was in large part of Hispanic ethnicity, circumstances that might preclude the generalization of our findings to populations with lower cardiovascular risk and different race-ethnic composition. Finally, because of the cross-sectional design of our study we cannot examine cause-effect relationships, but only document associations.

Conclusions

In our community cohort, LA volume and reservoir function were associated with silent brain infarcts and white matter hyperintensities. LAVmin showed stronger association with subclinical cerebrovascular disease than LAVmax, and this association was independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and potential confounders. The observation that LAVmin is more strongly correlated to subclinical cerebrovascular disease than LAVmax, together with its closer correlation with LV diastolic function and greater ability to predict atrial arrhythmias observed in previous studies, suggests that LAVmin may be a better marker of LA remodeling and cardiovascular risk. The echocardiographic evaluation of LA volume at end-diastole and of the LA reservoir function in clinical practice may improve the prognostic assessment of subjects at risk of cardiovascular events.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Janet De Rosa, MPH (project manager), Rafi Cabral, MD, Michele Alegre, RDCS, and Palma Gervasi-Franklin (collection and management of the data).

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) [grant number R01 NS36286 to MDT and R37 NS29993 to RLS/MSE].

Relationship with industry: None.

ABBREVIATIONS LIST

- SBI

Silent brain infarcts

- WMHV

White matter hyperintensity volume

- LAVmax

Left atrial maximum volume

- LAVmin

Left atrial minimum volume

- LAEV

Left atrial total emptying volume

- LAEF

Left atrial total emptying fraction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2012 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willey JZ, Moon YP, Paik MC, et al. Lower prevalence of silent brain infarcts in the physically active: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology. 2011;76:2112–2118. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821f4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermeer SE, Koudstaal PJ, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Prevalence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2002;33:21–25. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, et al. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: establishing what is normal. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard G, Wagenknecht LE, Cai J, Cooper L, Kraut MA, Toole JF. Cigarette smoking and other risk factors for silent cerebral infarction in the general population. Stroke. 1998;29:913–917. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ylikoski A, Erkinjuntti T, Raininko R, Sarna S, Sulkava R, Tilvis R. White matter hyperintensities on MRI in the neurologically nondiseased elderly. Analysis of cohorts of consecutive subjects aged 55 to 85 years living at home. Stroke. 1995;26:1171–1177. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.7.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price TR, Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, et al. Silent brain infarction on magnetic resonance imaging and neurological abnormalities in community-dwelling older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1997;28:1158–1164. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.6.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright CB, Paik MC, Brown TR, et al. Total homocysteine is associated with white matter hyperintensity volume: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2005;36:1207–1211. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165923.02318.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeer SE, Hollander M, van Dijk EJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2003;34:1126–1129. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000068408.82115.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuller LH, Longstreth WT, Jr, Arnold AM, Bernick C, Bryan RN, Beauchamp NJ., Jr White matter hyperintensity on cranial magnetic resonance imaging: a predictor of stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:1821–1825. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000132193.35955.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosley TH, Jr, Knopman DS, Catellier DJ, et al. Cerebral MRI findings and cognitive functioning: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Neurology. 2005;64:2056–2062. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165985.97397.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernick C, Kuller L, Dulberg C, et al. Silent MRI infarcts and the risk of future stroke: the cardiovascular health study. Neurology. 2001;57:1222–1229. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi S, Okada K, Koide H, Bokura H, Yamaguchi S. Subcortical silent brain infarction as a risk factor for clinical stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:1932–1939. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.10.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1215–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA, Levy D. Left atrial size and the risk of stroke and death. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1995;92:835–841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Tullio MR, Sacco RL, Sciacca RR, Homma S. Left atrial size and the risk of ischemic stroke in an ethnically mixed population. Stroke. 1999;30:2019–2024. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kizer JR, Bella JN, Palmieri V, et al. Left atrial diameter as an independent predictor of first clinical cardiovascular events in middle-aged and elderly adults: the Strong Heart Study (SHS) Am Heart J. 2006;151:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsang TS, Abhayaratna WP, Barnes ME, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular outcomes with left atrial size: is volume superior to area or diameter? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1018–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abhayaratna WP, Fatema K, Barnes ME, et al. Left atrial reservoir function as a potent marker for first atrial fibrillation or flutter in persons > or = 65 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1626–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fatema K, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, et al. Minimum vs. maximum left atrial volume for prediction of first atrial fibrillation or flutter in an elderly cohort: a prospective study. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:282–286. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sacco RL, Khatri M, Rundek T, et al. Improving Global Vascular Risk Prediction With Behavioral and Anthropometric Factors The Multiethnic NOMAS (Northern Manhattan Cohort Study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2303–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux RB, Reichek N. Echocardiographic determination of left ventricular mass in man. Anatomic validation of the method. Circulation. 1977;55:613–618. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.55.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, et al. Effect of obesity and overweight on left ventricular diastolic function: a community-based study in an elderly cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1368–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russo C, Hahn RT, Jin Z, Homma S, Sacco RL, Di Tullio MR. Comparison of echocardiographic single-plane versus biplane method in the assessment of left atrial volume and validation by real time three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:954–960. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, et al. Left atrial minimum volume and reservoir function as correlates of left ventricular diastolic function: impact of left ventricular systolic function. Heart. 2012;98:813–820. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermeer SE, den Heijer T, Koudstaal PJ, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Incidence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2003;34:392–396. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000052631.98405.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA, Levy D. Left atrial size and the risk of stroke and death. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1995;92:835–841. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masuda J, Nabika T, Notsu Y. Silent stroke: pathogenesis, genetic factors and clinical implications as a risk factor. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14:77–82. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200102000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fazekas F, Kleinert R, Offenbacher H, et al. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology. 1993;43:1683–1689. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.9.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Swieten JC, van den Hout JH, van Ketel BA, Hijdra A, Wokke JH, van Gijn J. Periventricular lesions in the white matter on magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly. A morphometric correlation with arteriolosclerosis and dilated perivascular spaces. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 2):761–774. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.2.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dijk EJ, Breteler MM, Schmidt R, et al. The association between blood pressure, hypertension, and cerebral white matter lesions: cardiovascular determinants of dementia study. Hypertension. 2004;44:625–630. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145857.98904.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henskens LH, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Kroon AA, Hofman PA, Lodder J, De Leeuw PW. Detection of silent cerebrovascular disease refines risk stratification of hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2009;27:846–853. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283232c96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eguchi K, Kario K, Hoshide S, et al. Smoking is associated with silent cerebrovascular disease in a high-risk Japanese community-dwelling population. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:747–754. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser AS, et al. Association of plasma total homocysteine levels with subclinical brain injury: cerebral volumes, white matter hyperintensity, and silent brain infarcts at volumetric magnetic resonance imaging in the Framingham Offspring Study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:642–649. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.5.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Oudkerk M, et al. Aortic atherosclerosis at middle age predicts cerebral white matter lesions in the elderly. Stroke. 2000;31:425–429. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manolio TA, Burke GL, O'Leary DH, et al. Relationships of cerebral MRI findings to ultrasonographic carotid atherosclerosis in older adults : the Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:356–365. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Kuller LH, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96:2455–2461. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flaker GC, Fletcher KA, Rothbart RM, Halperin JL, Hart RG. Clinical and echocardiographic features of intermittent atrial fibrillation that predict recurrent atrial fibrillation. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) Investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:355–358. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abhayaratna WP, Fatema K, Barnes ME, et al. Left atrial reservoir function as a potent marker for first atrial fibrillation or flutter in persons > or = 65 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1626–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Appleton CP, Galloway JM, Gonzalez MS, Gaballa M, Basnight MA. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressures using two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography in adult patients with cardiac disease. Additional value of analyzing left atrial size, left atrial ejection fraction and the difference in duration of pulmonary venous and mitral flow velocity at atrial contraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1972–1982. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barbier P, Solomon SB, Schiller NB, Glantz SA. Left atrial relaxation and left ventricular systolic function determine left atrial reservoir function. Circulation. 1999;100:427–436. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caselli S, Canali E, Foschi ML, et al. Long-term prognostic significance of three-dimensional echocardiographic parameters of the left ventricle and left atrium. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:250–256. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Artang R, Migrino RQ, Harmann L, Bowers M, Woods TD. Left atrial volume measurement with automated border detection by 3-dimensional echocardiography: comparison with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]