Abstract

Objective

To compare longer-term safety and effectiveness of the four most commonly used atypical antipsychotics (AAPs: aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) in 332 patients, aged >40 years, having psychosis associated with schizophrenia, mood disorders, PTSD, or dementia, diagnosed using DSM-IV-TR criteria.

Methods

We used Equipoise-Stratified Randomization (a hybrid of Complete Randomization and Clinician’s Choice Methods) that allowed patients or their treating psychiatrists to exclude one or two of the study AAPs, because of past experience or anticipated risk. Patients were followed for up to two years, with assessments at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and every 12 weeks thereafter. Medications were administered employing open-label design and flexible dosages, but with blind raters.

Outcome Measures

(1) Primary metabolic markers (body mass index or BMI, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides), (2) % patients who stay on the randomly assigned AAP for at least 6 months, (3) Psychopathology, (4) % patients who develop Metabolic Syndrome, and (5) % patients who develop serious and non-serious adverse events.

Results

Because of high incidence of serious adverse events, quetiapine was discontinued midway through the trial. There were significant differences among patients willing to be randomized to different AAPs, suggesting that treating clinicians tended to exclude olanzapine and prefer aripiprazole as one of the possible choices in patients with metabolic problems. Yet, the AAP groups did not differ in longitudinal changes in metabolic parameters or on most other outcome measures. Overall results suggested a high discontinuation rate (median duration 26 weeks prior to discontinuation), lack of significant improvement in psychopathology, and high cumulative incidence of metabolic syndrome (36.5% in one year) and of serious (23.7%) and non-serious (50.8%) adverse events for all AAPs in the study.

Conclusions

Employing a study design that closely mimicked clinical practice, we found a lack of effectiveness and a high incidence of side effects with four commonly prescribed AAPs across diagnostic groups in patients over age 40, with relatively few differences among the drugs. Caution in the use of these drugs is warranted in middle-aged and older patients.

Keywords: Antipsychotic, Metabolic Syndrome, Schizophrenia, Dementia, Mood disorder, Equipoise-Stratified Randomization

INTRODUCTION

Psychotic disorders are serious mental illnesses that usually need to be treated vigorously with effective therapy. Most treatment research in psychosis has focused on schizophrenia, and much less is known about management of psychotic disorders associated with other conditions such as PTSD or dementia. Antipsychotic drugs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) primarily for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, yet they are commonly used off-label for other psychotic disorders1–13. The risk of cardiovascular disease increases significantly over age 4014. Yet, 62% of all the prescriptions for antipsychotics in 2009–2010 were written for people aged >40 (IMS Health National Prescription Data Audit). A majority of antipsychotic prescriptions in patients over 40 involve off-label use of atypical antipsychotics (AAPs)2;15. However, there are inadequate published data on longer-term safety and effectiveness of AAPs in older patients with different diagnoses.

There has been a growing concern about cardiovascular and metabolic morbidity with certain AAPs such as olanzapine16–24. The FDA issued a warning regarding cerebrovascular adverse events and a boxed warning regarding increased mortality with AAP use for dementia-related psychosis, based on randomized controlled trials of 6–12 weeks duration25. Large ground-breaking randomized trials of AAPs such as CATIE26 and EUFEST27 did not have direct measures of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular pathology, as those studies were designed prior to the FDA warnings. Taken together, there is considerable public health interest in systematically assessing longer-term safety and effectiveness of AAPs in middle-aged and older patients.

The present study was designed as a hybrid of explanatory and pragmatic clinical trials28;29, for assessing the effects of the four most frequently used AAPs (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) in patients >40 years, with psychotic symptoms associated with various primary psychiatric disorders. The patients were followed for up to two years. We employed a practical randomization technique - Equipoise-Stratified Method30, few exclusion criteria, clinically relevant assessment procedures, open-label treatments, and as in the CATIE schizophrenia trial, no placebo group because of ethical considerations.

We hypothesized that there would be significant differences among the four AAPs in their effects on: (1) primary metabolic markers (body mass index or BMI, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides), (2) percentage of patients who stay on the randomly assigned AAP for at least 6 months, (3) psychopathology, (4) percentage of patients who develop the Metabolic Syndrome, and (5) percentage of patients who develop serious adverse events (SAEs) and non-serious adverse events (NSAEs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided a written informed consent.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were: age >40; DSM-IV-TR-based31 diagnosis of schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis associated with mood disorder, PTSD, or dementia, and either receiving AAPs at baseline or whose treating psychiatrists proposed to prescribe an AAP.

Exclusion criteria were: active substance abuse in the past 30 days; unstable medical conditions; and being treated with multiple antipsychotics at baseline. A total of 568 patients were screened (Figure 1), 406 signed consent, and 332 patients completed a baseline visit. The data reported in this paper reflect follow-up for up to two years on randomized medication (as proposed a priori).

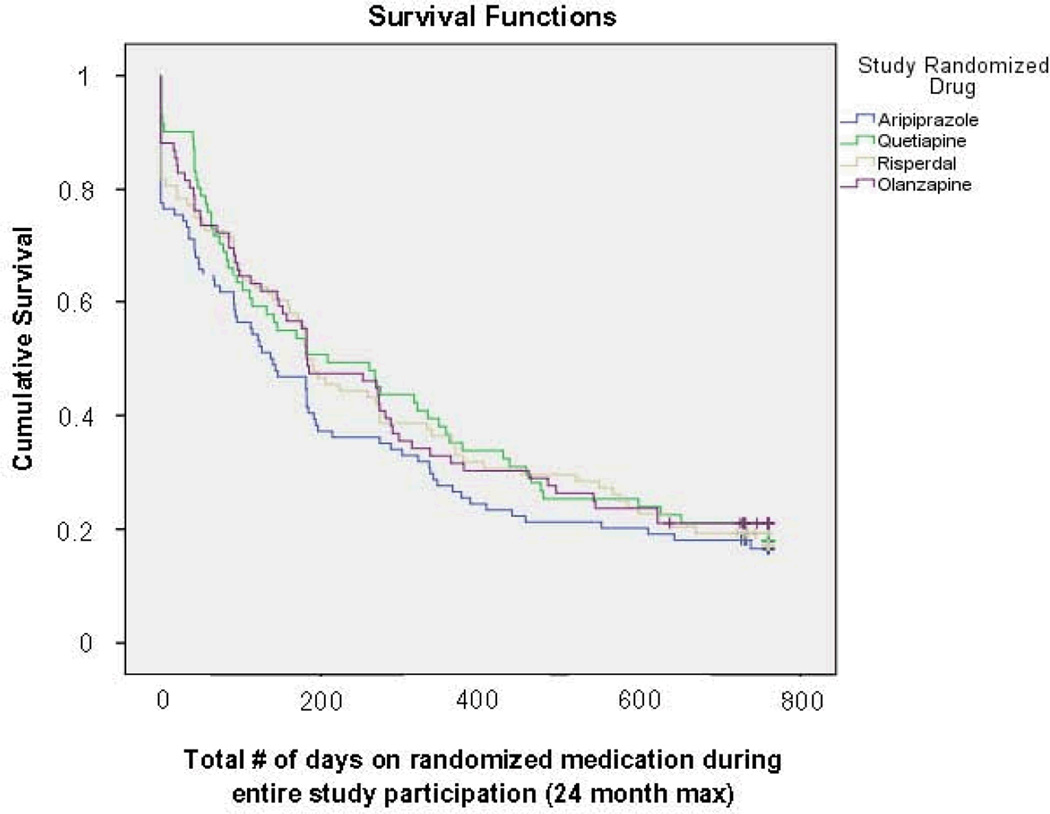

Figure 1.

Survival Curves for Time to Discontinuation of Randomized Medication

Survival analysis: χ2 =1.548, df=3, p=0.663 (Kalplan-Meier)

Equipoise-Stratified Randomization30

Our study design was a simplified version of that used in the NIMH-funded STAR*D trial30. This approach represents a balancing of advantages and disadvantages of a Completely Randomized Design (advantage = randomization; disadvantage = exclusion of patients for whom any one of the study treatments is unacceptable) and Clinician’s Choice Method (advantage = greater treatment flexibility for treating clinician; disadvantage = loss of ability to compare specific treatment options). The patient and his/her treating psychiatrist could exclude one or even two of the four study medications for randomization. (The patients who excluded three AAPs could not be randomized, and consequently those subjects were excluded from the trial). Thus each patient made a list of the medications to which s/he could be randomized. Depending on the number of AAPs excluded, this list included 2, 3, or 4 drugs that were acceptable for randomization and of rough parity to the patient – i.e., for him or her, the selected AAPs were approximately equal in terms of likelihood of success. This list was called “equipoise stratum.” The numbers of patients in each equipoise stratum are listed in Figure 1. Only 16.6% of the patients agreed to be randomized to all four medications – i.e., 83.4% patients would not have participated in a traditional randomized trial. All the consenting patients were randomly assigned with equal probability to one of the options within their respective lists. This procedure allowed pairwise contrasts of treatments, optimized the available recruitment resources, and enabled the greatest number of patients among different medication options30. Every pairwise comparison of AAPs was evaluated on all patients for whom that choice was acceptable (see below under “Statistical Analysis”). Randomized AAP was supplied to the patients at no cost, and in an open-label manner.

Reasons for refusing specific AAPs for randomization

The most common reason given for refusing specific AAPs was possible side effects, which ranged from 43% for aripiprazole to 78% for olanzapine. The percentages of patients citing lack of effectiveness as the reason for refusal ranged from 8% for olanzapine to 23% for quetiapine.

Clinical Assessment

Study raters were masked to the AAP assignment. For inter-rater reliability, an intraclass correlation coefficient of ≥0.80 for psychopathology measures was established. A summary of our baseline assessments has been published previously32. Briefly, the baseline evaluation included medical and medication history, physical examination (by trained physician assistants), anthropomorphic measurements including Body Mass Index (BMI) and waist circumference, psychopathology ratings (primarily, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale or BPRS)33, medication side effects33, and fasting plasma glucose and lipids. A clinical diagnosis of Metabolic Syndrome was made using standard AHA-modified NCEP guidelines34.

Follow-Up

The assessments were repeated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and then every 12 weeks.

Medication Management

After a patient was randomized to a study AAP, starting dosage was determined by the treating psychiatrist, who could alter the dose (or stop medication) anytime to meet the patient's needs.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data on all randomized patients in whom there was a baseline assessment and at least one post-baseline evaluation. These patients were stratified into subgroups (strata) defined by the treatments they had chosen to be randomized among. With a total of four treatments, there were 11 possible strata (Figure 1). Initially, all baseline characteristics were compared among these 11 strata groups with ANOVAs or chi-square analyses, adjusting for multiple comparisons using Tukey method. Next, data from different strata were pooled using all appropriate strata for each particular contrast for hypothesis testing. Four strata were involved for each pairwise comparison – e.g., to compare aripiprazole (A) and risperidone (R), we pooled data from all the strata that accepted both A and R (AOQR, AQR, AOR, and AR). Next, for each pair, the Risk Difference (RD = difference between the two proportions having a particular outcome with those drugs) was calculated. For longitudinal data on metabolic markers (BMI, blood pressure, glucose, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides) as well as BPRS, an individual’s slope across the first 6 months of study treatment was calculated. Group means were adjusted according to different randomization probabilities in different strata. Each pair of medications was compared using z-test, and a 95% two-tailed confidence interval was computed. Finally, we used survival analysis technique (Kaplan-Meier survival curves) to determine the cumulative probability of discontinuation for each of the randomized AAPs. Kaplan-Meier estimator is nonparametric, and requires no parametric assumptions. This survival analysis, which combines data on each AAP from diverse strata, is a simplified version of the more appropriate survival analysis with pairwise comparison, although the conclusions were similar.

RESULTS

The 332 patients who completed baseline visit and the 74 patients who dropped out after signing the consent were demographically and clinically similar, except that the study sample was older than the drop-outs: mean (SD) age 67 (13) vs. 62 (16) years, (df=1,404; f=7.4; p=0.007). The mean (SD) doses of the randomized medications prescribed during the study, in mg/day, were: aripiprazole (A) 10.8 (7), olanzapine (O) 8.8 (7), quetiapine (Q) 212 (211), and risperidone (R) 1.8 (2). The mean daily doses were highest in schizophrenia and lowest in dementia.

Comparison of Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics among the 11 Strata

The 11 strata groups differed from one another in gender, education, body weight, waist circumference, and fasting glucose (Table 1a and 1b). Pairwise strata analyses revealed that patients in Stratum AOQR patients had significantly lower waist circumference than those in AQR, AOQ and AR, while Stratum AQ patients had significantly higher fasting glucose levels that those in AOQR, AQR, AO, OQ, and OR, suggesting that the clinicians tended to exclude olanzapine but include aripiprazole in the list of acceptable medications for randomization among patients at risk for Metabolic Syndrome. The overall prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome was 50% at baseline visit. There was a significant difference in the proportions of people with different diagnoses in terms of those who had vs. did not have Metabolic Syndrome at baseline (χ2 = 14.56; df = 3; p = 0.002). Patients with dementia had a significantly lower proportion of those who had Metabolic Syndrome at baseline, compared to those with other diagnoses. This possibly could be attributed to differences in duration and daily doses of AAPs at baseline; however, retrospective information on AAP use prior to baseline assessment was of uncertain reliability.

Table 1.

| a. Baseline Demographic Data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Strata | Age | Gendera (%M) |

Educationa (years) |

Diagnosis | ||

| Scz/Scz Aff/Bipolar | Other | |||||

| AOQR | N | 55 | 55 | 52 | 21 | 34 |

| Mean or % | 64.1 | 60.00% | 13.3 | 38% | 62% | |

| Std. Deviation | 12.3 | na | 2.6 | na | na | |

| AQR | N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 8 | 11 |

| Mean or % | 60.3 | 73.70% | 14.5 | 42% | 58% | |

| Std. Deviation | 8.2 | na | 2 | na | na | |

| AOR | N | 38 | 38 | 36 | 16 | 22 |

| Mean or % | 69.4 | 63.20% | 10.6 | 42% | 58% | |

| Std. Deviation | 14.2 | Na | 5 | na | na | |

| AOQ | N | 18 | 18 | 15 | 7 | 11 |

| Mean or % | 63.9 | 66.70% | 14.2 | 39% | 61% | |

| Std. Deviation | 12.3 | na | 2.3 | na | na | |

| OQR | N | 17 | 17 | 17 | 3 | 14 |

| Mean or % | 68.7 | 94.10% | 12.5 | 18% | 82% | |

| Std. Deviation | 15.2 | na | 2 | na | na | |

| AR | N | 60 | 60 | 59 | 22 | 38 |

| Mean or % | 66.6 | 85% | 13.7 | 37% | 63% | |

| Std. Deviation | 13.4 | Na | 2.4 | na | na | |

| AQ | N | 25 | 25 | 24 | 15 | 10 |

| Mean or % | 64.7 | 52% | 13.4 | 60% | 40% | |

| Std. Deviation | 12.8 | na | 3.2 | na | na | |

| AO | N | 25 | 25 | 24 | 12 | 13 |

| Mean or % | 64.4 | 52.00% | 13.5 | 48% | 52% | |

| Std. Deviation | 12.3 | na | 2.4 | na | na | |

| QR | N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 6 | 10 |

| Mean or % | 67 | 75% | 13.4 | 38% | 63% | |

| Std. Deviation | 14 | Na | 2.9 | na | na | |

| OR | N | 26 | 26 | 25 | 10 | 16 |

| Mean or % | 70.7 | 65.40% | 12.6 | 38% | 62% | |

| Std. Deviation | 12.4 | na | 2.2 | na | na | |

| OQ | N | 33 | 33 | 32 | 8 | 25 |

| Mean or % | 70.6 | 60.60% | 13.8 | 24% | 76% | |

| Std. Deviation | 13.9 | na | 3.1 | na | na | |

| Total | N | 332 | 332 | 319 | 128 | 204 |

| Mean or % | 66.6 | 67.80% | 13.2 | 39% | 61% | |

| Std. Deviation | 13.1 | na | 3.1 | na | na | |

| b. Baseline Clinical Data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Strata | BPRS Total | Waist Circumferencea (inches) |

Body Weighta (kg) |

Fasting Glucosea (mg/dL) |

|

| AOQR | N | 41 | 54 | 54 | 45 |

| Mean | 41.2 | 38.0 | 79.0 | 101.0 | |

| Std. Deviation | 11.3 | 6.3 | 20.6 | 26.4 | |

| AQR | N | 19 | 19 | 19 | 16 |

| Mean | 42.2 | 43.6 | 96.9 | 101.3 | |

| Std. Deviation | 8.3 | 7.5 | 25.5 | 17.0 | |

| AQR | N | 17 | 37 | 38 | 32 |

| Mean | 38.0 | 39.2 | 80.8 | 120.7 | |

| Std. Deviation | 7.8 | 5.2 | 24.4 | 71.3 | |

| AOQ | N | 12 | 14 | 16 | 13 |

| Mean | 37.4 | 43.8 | 97.4 | 106.4 | |

| Std. Deviation | 7.4 | 8.2 | 26.3 | 32.4 | |

| OQR | N | 12 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| Mean | 38.4 | 40.0 | 84.4 | 104.3 | |

| Std. Deviation | 9.5 | 4.0 | 12.9 | 40.9 | |

| AR | N | 49 | 59 | 60 | 49 |

| Mean | 38.1 | 41.9 | 89.7 | 117.1 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.6 | 5.6 | 18.3 | 44.0 | |

| AQ | N | 18 | 23 | 24 | 17 |

| Mean | 44.9 | 38.8 | 83.8 | 159.4 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.1 | 6.9 | 22.1 | 120.6 | |

| AO | N | 19 | 24 | 25 | 20 |

| Mean | 43.7 | 38.9 | 81.3 | 102.8 | |

| Std. Deviation | 12.2 | 5.7 | 23.0 | 27.6 | |

| QR | N | 12 | 15 | 15 | 9 |

| Mean | 41.3 | 39.4 | 84.7 | 110.1 | |

| Std. Deviation | 13.0 | 4.6 | 19.2 | 50.4 | |

| OR | N | 18 | 25 | 26 | 24 |

| Mean | 35.4 | 38.4 | 76.7 | 104.4 | |

| Std. Deviation | 6.9 | 5.4 | 18.0 | 21.6 | |

| OQ | N | 21 | 31 | 32 | 24 |

| Mean | 40.7 | 39.0 | 80.4 | 98.5 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.0 | 5.1 | 18.6 | 21.3 | |

| Total | N | 238 | 316 | 325 | 265 |

| Mean | 40.1 | 39.9 | 84.1 | 111.1 | |

| Std. Deviation | 10.3 | 6.1 | 21.4 | 50.4 | |

A = Aripiprazole

O = Olanzapine

Q = Quetiapine

R = Risperidone

Scz/Scz Aff = Schizophrenia / Schizoaffective disorders

na = not applicable

= There were significant differences among the strata groups on these variables.

1) Gender: Group difference: χ2=22.68, df = 10, p=0.012

Post-hoc pairwise significant differences: There were higher proportions of male patients in the strata OQR and AR than in a majority of other strata.

2) Education: Group difference: F=3.996, df =10,308, p < 0.001.

Post-hoc pairwise significant differences: AOR<AOQR, AQR, AOQ, AR, AQ, AO, and OQ.

A = Aripiprazole

O = Olanzapine

Q = Quetiapine

R = Risperidone

Scz/Scz Aff = Schizophrenia / Schizoaffective disorders

na = not applicable

= There were significant differences among the strata groups on these variables.

1) Waist Circumference: Group difference: F=3.089, df=10,315, p=0.001.

Post-hoc pairwise significant differences: AR stratum had higher waist circumference than all other strata.

2) Body Weight: Group difference: F=2.695, df=10,314, p=0.004)

Post-hoc pairwise significant differences: AR stratum had higher body weight than all other strata.

3) Fasting Glucose: Group difference: F=2.402, df=10,254, p=0.01.

Post-hoc pairwise significant differences: AQ>AOQR, AQR, AO, OQ, and OQ

Time to Discontinuation of Randomized Drug

The proportion of patients who discontinued their randomized medication before the end of the 2-year follow-up period ranged from 78.6% on quetiapine to 81.5% on aripiprazole. The median number of weeks to discontinuation of randomized medication was 26.0 weeks (25th percentile = 6.0; 75th percentile = 75.9). It is possible that the early discontinuation reflected significant clinical improvement or at least, adherence to the treatment guidelines for using AAPs for as short a period as possible, especially in patients with dementia35. However, there was no relationship between diagnosis and duration of AAP treatment. A majority of the patients whose randomized AAP was discontinued were switched to another AAP by their own treating clinicians. Among the patients with known reasons for discontinuation, 51.6% did so due to side effects, 26.9 % for lack of effectiveness, and 21.5% for other reasons. Figure 1 shows survival curves for the four AAPs in terms of time to discontinuation of medication. There were no significant differences among the four drugs on this measure. However, using a cut-off point of 6 months’ duration of AAP use (as included in our a priory hypothesis), the percentage of patients who stayed on the randomized medication for at least 6 months was significantly lower for aripiprazole than for olanzapine (Table 2). There was no significant association between the stratum group and reason for medication discontinuation.

Table 2.

Pair-wise Strata Analysis for Categorical Outcome Measures

| Drug 1 (n) |

Drug 2 (n) | Drug 1% | Drug 2% | RD % | RD 95% confidence interval |

Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Patients who Stayed on Randomized Medication for At Least 6 Months | |||||||

| A (66) | R (66) | 32 | 48 | −16 | −0.37 to 0.049 | −1.5 | 0.13 |

| A (42) | Q (39) | 39 | 58 | −19 | −0.47 to +0.085 | −1.36 | 0.17 |

| A (44) | O (40) | 26 | 58 | −31 | −0.57 to −0.05 | −2.37 | 0.02a |

| R (30) | Q (35) | 67 | 49 | 17 | −0.12 to +0.47 | 1.15 | 0.25 |

| R (50) | O (41) | 67 | 58 | 9 | −0.16 to +0.34 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| Q (41) | O (40) | 56 | 58 | −2 | −0.33 to +0.28 | −0.17 | 0.87 |

| % Patients who Developed Metabolic Syndrome within a Year | |||||||

| A (66) | R (65) | 85 | 87 | −2 | −0.21 to +0.17 | −0.22 | 0.83 |

| A (39) | Q (38) | 82 | 88 | −5 | −0.29 to +0.19 | −0.43 | 0.67 |

| A (41) | O (38) | 86 | 55 | 34 | 0.07 to +0.60 | 2.47 | 0.01a |

| R (29) | Q (34) | 93 | 67 | 26 | −0.01 to +0.52 | 1.89 | 0.06 |

| R (48) | O (39) | 71 | 65 | 6 | −0.21 to +0.33 | 0.46 | 0.65 |

| Q (39) | O (37) | 77 | 65 | 12 | −0.14 to +0.39 | 0.93 | 0.35 |

| % Patients who Developed Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) | |||||||

| A (63) | R (64) | 23 | 12 | 11 | −0.06–0.28 | 1.27 | 0.10 |

| A (40) | Q (38) | 27 | 33 | −5 | −0.30 to +0.19 | −0.43 | 0.67 |

| A (42) | O (39) | 23 | 28 | −5 | −0.28 to +0.18 | −0.46 | 0.65 |

| R (29) | Q (35) | 17 | 35 | −18 | −0.433 to +0.07 | −1.41 | 0.16 |

| R (49) | O (40) | 20 | 27 | −7 | −0.28 to +0.14 | −0.64 | 0.52 |

| Q (41) | O (39) | 34 | 30 | 4 | −0.22 to 0.305 | 0.3 | 0.76 |

| % Patients who Developed Non-Serious Adverse Events (NSAEs) | |||||||

| A (63) | R (64) | 52 | 52 | 0 | −0.25 to 0.25 | −0.006 | 1.00 |

| A (40) | Q (38) | 64 | 59 | 5 | −0.022 to +0.33 | 0.037 | 0.97 |

| A (42) | O (39) | 49 | 78 | −29 | −0.55 to −0.026 | −2.16 | 0.03a |

| R (29) | Q (35) | 57 | 51 | 6 | −0.25 to +0.37 | 0.37 | 0.71 |

| R (49) | O (40) | 46 | 73 | −27 | −0.53 to −0.006 | −2.01 | 0.04a |

| Q (41) | O (39) | 69 | 79 | −10 | −0.38 to +0.18 | −0.69 | 0.95 |

A = Aripiprazole

O = Olanzapine

Q = Quetiapine

R = Risperidone

RD = Risk Difference

= Statistical significance is defined as p < 0.05

Discontinuation of Quetiapine During the Trial

Approximately 3.5 years after the study began, our Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) concluded that there was a significantly higher incidence of SAEs with quetiapine (38.5%) than with the other three AAPs (19.0%, χ2=9.56, df=1, p=0.002). These differences were not related to age, prior antipsychotic treatment, medical burden, or duration of treatment. Consequently, quetiapine arm of the trial was discontinued. These interim data on SAEs were published as a Letter to Editor36.

Psychopathology

We found no significant main effects of stratum, visit, or medication, or any two-way or three-way interactions for BPRS total and psychosis subscale scores, suggesting no significant change in psychopathology with any of the study AAPs.

Effects on Primary Metabolic Markers (BMI, blood pressure, glucose, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides)

There were no significant differences among the drug groups on these measures.

Incidence of Metabolic Syndrome

Cumulative one-year incidence of Metabolic Syndrome (among those patients who did not meet the criteria for Metabolic Syndrome at baseline) was 36.5 %. There were no significant differences among the strata-eligible patients in the proportion of subjects developing Metabolic Syndrome except for the aripiprazole - olanzapine pair-wise comparison: 86% of patients on aripiprazole developed Metabolic Syndrome compared to 55% on olanzapine in one year (RD = 34%; p=0.013).

Serious (SAEs) and Non-serious Adverse Events (NSAEs)

Overall 23.7% of the patients treated with different AAPs developed SAEs including deaths, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits for life threatening conditions (χ2 = 13.43, df =3, p = 0.004), while 50.8% developed NSAEs (χ2 = 8.57, df=3, p = 0.035) within 24 months of follow-up. Pair-wise medication comparisons found no significant differences in proportion of subjects developing SAEs. However, in comparing NSAEs, 49% of aripiprazole users versus 78% of quetiapine users developed NSAEs (p = 0.03), and 46% of risperidone patients versus 73% of olanzapine patients developed NSAEs (p = 0.04).

The two conditions for which there is an FDA warning (cerebrovascular adverse events) or boxed warning (mortality) for AAPs in older dementia patients occurred in six patients. Two 75-year-old patients with mood disorders (but none with dementia), developed transient ischemic attack or stroke, one on aripiprazole and one on quetiapine. Four patients, aged 74–89 years, died, including three with dementia, (one each on aripiprazole, olanzapine, and quetiapine) and a 51-year-old patient with schizophrenia and late-stage cancer (on quetiapine). There was no consistent underlying cause for cerebrovascular accident or death in these patients.

Relationship of outcome measures to other variables

With one exception, there was no significant relationship of AAP daily dose with length of time patients stayed on their randomized medication, or development of Metabolic Syndrome, SAEs, or NSAEs. The only exception was that higher daily dose of aripiprazole was significantly associated with greater risk of developing SAEs and NSAEs (F = 6.6, df =1,86, p =.012). Development of side effects (Metabolic Syndrome, SAEs, and NSAEs) was not related to diagnosis or concurrent medications. However, older age was significantly associated with a greater incidence of SAEs (F = 8.080; df = 1,323; p = .005).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggested a high discontinuation rate following a relatively short duration of drug treatment (median of 26 weeks), lack of significant improvement in psychopathology (on BPRS), high incidence of metabolic syndrome (36.5% in one year), and of serious (23.7%) and non-serious (50.8%) adverse events with AAPs. These results are worrisome since we had given a choice to the patients and their psychiatrists to exclude one or two of the four AAPs for possible safety or effectiveness concerns. The clinicians could choose the daily dosage and change it as needed at any time. The daily dosages of the AAPs prescribed were relatively low. Thus, we had sought to give all the study AAPs the best chance of proving safe and effective, as is done in good clinical practice.

Designing a pragmatic clinical trial involves trade-offs between an ideal experimental design and practical considerations that would enhance its applicability to routine clinical management of patients. There is a certain amount of bias in almost every clinical trial. We believe that the Equipoise-Stratified Randomization provided the least amount of bias for this “real world” type of investigation. Only 16.6% of the patients agreed to be randomized to all four medications. Thus, a traditional randomization design would have resulted in exclusion of 83.4% of the patients who participated in this study and thus, the study sample would not have been representative of the population to which clinical decisions are relevant. The conclusions of a traditional randomized trial apply only to those patients who are willing to accept randomization to any one of the drugs in that trial. Therefore, the success or failure rate of a drug when compared to placebo may not be the same as that when compared to an active comparator, not only because the comparator is different, but also because the population sampled is different – e.g., patients who refuse a placebo trial are different from those who refuse a trial in which olanzapine is used.

The flexibility that we offered to the patients and their treating psychiatrists in allowing them to exclude one or two AAPs because of past experience or anticipated side effects led to expected differences in baseline characteristics of the medication groups. Thus, the patients who seemed to have a greater risk of developing Metabolic Syndrome (e.g., high BMI) excluded olanzapine as a possible medication due to a fear of additional metabolic problems19;37. Similarly, there is a channeling or allocation bias38, when claimed advantages of a new drug channel it to patients with special pre-existing morbidity - e.g., the reportedly lower propensity of aripiprazole to cause adverse metabolic effects might have resulted in a greater likelihood of its being included in the list of medications acceptable for patients at risk of Metabolic Syndrome, such as those with abdominal obesity or elevated fasting blood glucose levels. Therefore, our findings of baseline differences among patient groups in different strata support the pragmatic value of the present study – in real life, clinicians prefer aripiprazole to olanzapine for patients at higher risk of Metabolic Syndrome. Yet, the reported metabolic advantages of aripiprazole compared to olanzapine were not borne out in this study. The higher incidence of Metabolic Syndrome with aripiprazole likely was related to the fact that the patients who included that drug in their list of acceptable medications were at a greater risk of developing the Metabolic Syndrome at baseline than those who opted for olanzapine. The main point here is that aripiprazole did not prove to be safe in high-risk patients.

Metabolic Syndrome is reported to be associated with increased risk of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and heart disease39;40. The prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the older adults of the general population is reported to be 24%–44%41–44. The high baseline prevalence as well as elevated one-year incidence rates of Metabolic Syndrome observed in our patients raise concerns about psychiatric patients’ cardiometabolic and cerebrovascular health.

Quetiapine was removed from the trial before the study was completed because of the observed high incidence of SAEs36. This finding is consistent with a report by Tiihonen et al45, who found that the standardized mortality rate with quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia was twice that with clozapine. Similarly, quetiapine was recently removed by the U.S. Central Command from its approved formulary list due to medication- associated mortality46.

Our study has several limitations. This was a sample of patients aged >40; hence, our results may not generalize to younger patients. Some patients had been treated previously with different antipsychotics for varying duration, and those drugs might have contributed to metabolic changes seen early in our trial. Our sample included patients with different psychiatric disorders. The sample sizes in individual diagnostic groups were inadequate for testing small to medium size differences. Our study findings may not be applicable to newer antipsychotics such as lurasidone or iloperidone. Although we sought to make our study design mimic clinical practice, the two are not the same, and therefore, our results may not apply fully to everyday care. For example, in the real world, patients are not randomized. Lastly, it is usually not possible to conclude that an SAE observed during the treatment is causally related to that drug.

Notwithstanding the limitations, the results of our study are sobering. One-half of the patients remained on the assigned drug for less than six months. Furthermore, there was no significant improvement in BPRS total or psychosis subscale scores over a six-month period, and there was a high incidence of Metabolic Syndrome, SAEs, and NSAEs. While there were a few significant differences among the four AAPs included in this study, the overall risk-benefit ratio for the AAPs in patients over age 40 was not favorable, irrespective of diagnosis and drug.

The use of AAPs in older psychotic patients presents a major clinical dilemma. Psychotic disorders, including those associated with conditions other than schizophrenia, have severe adverse consequences for the medical health, career, family, and quality of life of sufferers. AAPs, although not approved for these conditions, are commonly used off-label in these patients, and there are few, if any, evidence-based treatment alternatives in older patients with psychotic disorders. Indeed, Tiihonen et al45 reported that no treatment with an antipsychotic was associated with higher mortality than treatment with an AAP. Thus there are risks associated with either no treatment or treatment with other medications including typical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers35. At the same time, the low safety and effectiveness of AAPs found in our study, along with the high costs of these medications, make their use problematic.

Our findings do not suggest that AAPs should be banned in older patients with psychotic disorders. There are currently no safe and effective treatment alternatives in these patients. Short-term use of AAPs is often necessary for controlling severe psychotic symptoms. Also, specific AAPs in low dosages may be useful for longer treatment of certain patients. However, our results and other reports47 do indicate that considerable caution is warranted in off-lable long-term use of AAPs in older persons. Psychosocial treatments should be used whenever appropriate. Pharmacotherapeutic guidelines for “start low and go slow” should be followed along with close monitoring and medical management for metabolic side effects. Shared decision making, involving detailed discussions with the patients and their family members or legal guardians about the risks and benefits of AAPs and of possible treatment alternatives as well as of no pharmacologic treatment, is warranted1;35. Clearly, there is a critical need to develop and test new interventions that are safe and effective in older people with psychotic disorders.

Clinical Points.

Caution is needed in long-term use of commonly prescribed atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) in middle-aged and older patients with psychotic disorders.

When these medications are used, they should be given in low dosages, for short durations, and their side effects monitored closely.

Shared decision making with patients and their caregivers is recommended, including discussions of risks and benefits of atypical antipsychotics and those of available treatment alternatives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health grants (MH071536, P30 MH080002-01, 1K01DK087813-01, NCRS UL1RR031980) and by the department of Veterans Affairs. It was carried out, in part, in the General Clinical Research Center, University of California, San Diego with funding provided by the National Center for Research Resources, M01RR 000827 United States Public Health Service.

AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Janssen Scientific Affairs, L.L.C. donated quetiapine, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and risperidone, respectively, for this NIMH-funded study.

We wish to thank Rebecca Daly who managed the complex longitudinal dataset. She has had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Footnotes

Hua Jin, MD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: He and his spouse have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Pei-an Betty Shih, PhD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: She and her spouse have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Shahrokh Golshan, PhD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: He and his spouse have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Sunder Mudaliar, MD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: He is a Consultant and on the Speaker's Bureau for Astra-Zeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb which manufacture the drugs used in this study.

Robert Henry, MD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: He and his spouse/partner have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Danielle K. Glorioso, MSW. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: She and her spouse have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Stephan Arndt, PhD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: He and his spouse/partner have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Helena C. Kraemer, PhD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: She and her spouse have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Dilip V. Jeste, MD. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: He and his spouse have had no relevant financial interests or personal affiliations during at least the past 12 months.

Contributor Information

Hua Jin, University of California, San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System.

Pei-an Betty Shih, University of California, San Diego.

Shahrokh Golshan, University of California, San Diego.

Sunder Mudaliar, University of California, San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System.

Robert Henry, University of California, San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System.

Danielle K. Glorioso, University of California, San Diego.

Stephan Arndt, University of Iowa.

Helena C. Kraemer, Stanford University and University of Pittsburgh.

Dilip V. Jeste, University of California, San Diego.

References

- 1.Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: Consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889–898. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeste DV, Dolder CR. Treatment of non-schizophrenic disorders: Focus on atypical antipsychotics. J Psychiat Research. 2003;38:73–103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: Research agenda for the next two decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:848–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexopoulos GS, Streim JE, Carpenter D. Expert consensus guidelines for using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:5–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald WM, Wermager J. Pharmacologic treatment of geriatric mania. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the department of Veterans Affairs health care system. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1175–1181. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamble P, Sherer J, Chen H, et al. Off-label use of second-generation antipsychotic agents among elderly nursing home residents. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:130–136. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306:1359–1369. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterreus A, Morgan V, Castle D, et al. Medication for psychosis - consumption and consequences: The second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012 Jun 11; doi: 10.1177/0004867412450471. [Epub ahead of print]: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozaric-Kovacic D, Pivac N, Muck-Seler D, et al. Risperidone in psychotic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: an open trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:922–927. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozaric-Kovacic D, Pivac N. Quetiapine treatment in an open trial in combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder with psychotic features. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:253–261. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Pharmacotherapy of PTSD in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: diagnostic- and symptom-guided drug selection. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:959–965. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viana BM, Prais HA, Nicolato R, et al. Posttraumatic brain injury psychosis successfully treated with olanzapine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, et al. Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: New indications and new populations. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey DE. Metabolic issues and cardiovascular disease in patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 2):15S–22S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goff DC, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE study and matched controls. Schiophr Res. 2005;80:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daumit GL, Goff DC, Meyer JM, et al. Antipsychotic effects on estimated 10-year coronary heart disease risk in the CATIE schizophrenia study. Schizophr Res. 2008;105:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wirshing DA, Boyd JA, Meng LR, et al. The effects of novel antipsychotics on glucose and lipid levels. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:856–865. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin H, Meyer JM, Jeste DV. Atypical antipsychotics and glucose dysregulation: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2004;71:195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons B, Allison DB, Loebel A, et al. Weight effects associated with antipsychotics: A comprehensive database analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;110:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermes E, Nasrallah H, Davis V, et al. The association between weight change and symptom reduction in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res. 2011;128:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman R. The choice of antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1286–1288. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer JM, Davis VG, Goff DC, et al. Change in metabolic syndrome parameters with antipsychotic treatment in the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial: Prospective data from phase 1. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA Public Health Advisory. Deaths with Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Behavioral Disturbances. 2005 Available: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm053171.htm.

- 26.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: An open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancey CM. Increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290:1624–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacPherson H. Pragmatic clinical trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2004;12:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Strengthening clinical effectiveness trials: Equipoise-stratified randomization. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:792–801. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin H, Lanouette NM, Mudaliar S, et al. Association of post-traumatic stress disorder with increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:210–215. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a45ed0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grundy SM, Hansen B, Smith SC, Jr, et al. Clinical management of metabolic syndrome: Report of the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Diabetes Association conference on scientific issues related to management. Circulation. 2004;109:551–556. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112379.88385.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeste DV, Blazer D, Casey DE, et al. ACNP White Paper: Update on the use of antipsychotic drugs in elderly persons with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:957–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeste DV, Jin H, Golshan S, et al. Discontinuation of quetiapine from an NIMH-funded trial due to serious adverse events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:937–938. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petri H, Urquhart J. Channeling bias in the interpretation of drug effects. Stat Med. 1991;10:581. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obunai K, Jani S, Dangas GD. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality of the metabolic syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:1169–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenzo C, Williams K, Hunt KJ, et al. The National Cholesterol Education Program - Adult Treatment Panel III, International Diabetes Federation, and World Health Organization definitions of the metabolic syndrome as predictors of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;30:8–13. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the elderly population according to IDF, WHO, and NCEP definitions and associations with C-reactive protein: The KORA Survey 2000. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:461. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravaglia G, Forti P, Maioli F, et al. Metabolic Syndrome: Prevalence and prediction of mortality in elderly individuals. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2471–2476. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Morrell CH, et al. The metabolic syndrome in older individuals: prevalence and prediction of cardiovascular events: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:882–887. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US Adults: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A population-based cohort study (FIN11 study) Lancet. 2009;374:620–627. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kime P. DoD cracks down on off-label drug use. Army Times. 2012 Jun 14; [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ballard C, Hanney ML, Theodoulou M, et al. The dementia antipsychotic withdrawal trial (DART-AD): Long-term follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]