Abstract

Members of the Rhabdoviridae infect a wide variety of animals and plants, and are the causative agents of many important diseases. Rhabdoviruses enter host cells following internalization into endosomes, with the glycoprotein (G protein) mediating both receptor binding to host cells and fusion with the cellular membrane. The recently solved crystal structure of vesicular stomatitis virus G has allowed considerable insight into the mechanism of rhabdovirus entry, in particular the low pH-dependent conformational changes that lead to fusion activation. Rhabdovirus entry shows several distinct features compared with other enveloped viruses; first, the entry process appears to consist of two distinct fusion events, initial fusion into vesicles within endosomes followed by back-fusion into the cytosol; second, the conformational changes in the G protein that lead to fusion activation are reversible; and third, the G protein is structurally distinct from other viral fusion proteins and is not proteolytically cleaved. The internalization and fusion mechanisms of rhabdoviruses are discussed in this article, with a focus on viral systems where the G protein has been studied extensively: vesicular stomatitis virus and rabies virus, as well as viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus.

Keywords: membrane fusion, rabies, viral receptor, virus entry, VSV

The Rhabdoviridae encompass more than 150 viruses of vertebrates, invertebrates and plants [1]. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), in the Vesiculovirus genus, is a prototypic virus in the family. There are two major serotypes of VSV, New Jersey and Indiana, both of which can infect insects and mammals, causing economically important diseases in cattle, equines and swine [1]. The commonly studied laboratory strains of VSV are members of the Indiana serotype. Besides VSV, other important human and animal pathogenic viruses in the Rhabdoviridae include rabies virus (RABV) from the Lyssavirus genus [1], the viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) and infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus, both from the Novirhabdovirus genus, and both of which infect fish [2].

The VSV genome is composed of single-stranded, negative-sense RNA of between 11,000 and 12,000 nucleotides, which encodes five viral proteins [3]. In the virion, viral RNA is surrounded by approximately 1200 molecules of nucleoprotein and limited copies of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase protein L and phosphoprotein P to form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) core [1]. Rhabdoviruses have an envelope that is derived from the host during viral budding from the host plasma membrane. Glycoprotein (G protein) monomers associate to form a trimer, with approximately 400 trimeric spikes anchored in the viral membrane. The VSV G protein of the Indiana serotype is synthesized as a precursor of 511 amino acids, including the N-terminal signal sequence of 16 amino acids, which is cleaved during protein insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum. The G protein is responsible for both viral attachment and fusion within endosomal vesicles [1].

To initiate viral replication in host cells, enveloped viruses need to fuse with the lipid bilayer of the host cell, and release the viral genome and associated proteins into the cytoplasm of target cells. Rhabdoviruses are endocytosed into host cells upon receptor binding, and the subsequent acidic environment of the endosome triggers conformational changes in the G protein, leading to fusion between the viral envelope and the endosomal membrane. Over the past years, significant developments, including the live imaging of VSV endocytosis and the determination of the VSV G protein crystallographic structure, have advanced our understanding of rhabdovirus entry. The entry process leading to viral infection will be reviewed in this article, with a focus on VSV, RABV and VHSV, including highlights of recent progress.

Receptor utilization by glycoprotein G

Owing to the exceedingly wide host range of VSV, it has been difficult to identify its cellular receptor using conventional approaches. Initial studies on VSV binding properties revealed that cells exposed to diethylaminoethyl-dextran, trypsin or neuraminidase had enhanced viral binding [4]. This led to the suggestion that the binding site for VSV was saturable and that there were approximately 4000 high-affinity binding sites on the surface of Vero cells, implying the existence of a specific receptor for viral attachment [5]. A seminal study in the early 1980s described Vero cell membrane extracts that demonstrated inhibitory effects on viral binding could be inactivated by treatment with phospholipase C, but not by protease, neuraminidase or heat treatment [6]. Furthermore, it was shown in the same study that purified phosphatidylserine (PS) was able to greatly inhibit VSV binding, as compared with only marginal inhibition induced by other phospholipids, leading the authors to conclude that PS might be a cellular binding site for VSV. The significance of interaction between PS and VSV in viral binding and infection was confirmed in other tissues and cell lines [7]. However, the likelihood of PS being the receptor for VSV was challenged by a recent study in which no correlation between viral infectivity and the level of PS in the membrane of various cell lines was established, and saturation of existing PS with annexin V failed to block viral infection [8]. In addition, the fact that PS is predominantly located in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and limited PS molecules on the outer leaflet have a very short half-life also appears to put into doubt the assumption that PS is the cellular receptor for VSV [9]. In this regard, it is interesting to note that VHSV is able to induce translocation of PS from the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane to the outer leaflet [10]. Despite the disagreement on PS as the cellular receptor, there is no doubt that VSV can interact with PS and the interaction is stronger at an acidic pH. Recent studies have identified the regions and critical residues in the G protein involved in binding to PS. Using pepscan solid-phase binding assays, a stretch of amino acids from 82 to 109 in the hydrophobic heptad repeat region of the glycoprotein of VHSV, called the p2 peptide, was identified to have a higher binding affinity for PS than other regions of the G protein [11]. The p2 peptide was later shown to insert into liposomal membranes by adopting a β-sheet structure, thereby causing leakage of liposomal contents [12]. Interestingly, binding of the p2 peptide to PS is pH independent, in contrast to optimal binding at pH 5.6 between whole virions and PS, suggesting that the p2 peptide may not be well exposed at physiological pH, and low pH-induced conformational changes in G protein may enhance its interaction with PS [11]. Synthetic peptides from a similar p2-like sequence in the G protein of other rhabdoviruses including VSV amino acids 145–168(129–152), and RABV amino acid 147–171 have also been shown to bind to PS [13]. (Italicized numbers in parentheses are based on the nomenclature used in protein databank (PDB) files 2cmz and 2j6j, which are numbered starting after the VSV G signal peptide of 16 amino acids.) Further investigation of the binding properties of the VSV G p2-like peptide using atomic-force microscopy suggested that binding was dependent on the presence of histidine residues in this region [14]. In addition, a different region from amino acids 118–136(102–120) in the VSV G protein, which is upstream of the p2-like peptide, has also been shown to interact with PS, with the interaction modulated by both ionic and hydrophobic factors along the length of the peptide [15]. Taken together, we can summarize that VSV binds to PS with high affinity and the interaction between PS and the G protein may play an important role in the early steps of viral entry, although the role of PS as the primary cellular receptor for VSV requires further study. Indeed, the use of other membrane components, including proteinaceous molecules, cannot be completely ruled out as the VSV receptor. Previous viral-binding assay studies using cell membranes pretreated with protease might have inactivated a natural VSV receptor, resulting in viral interaction with PS becoming more dominant, thereby, hindering the identification of the true cellular receptor for VSV. Alternatively, the virus might first bind to a receptor with low affinity, causing the G protein to better expose the PS-binding region; this conformational change may resemble that which is induced at acidic pH. Based on current studies, it would be interesting to investigate receptor binding using mutant forms of VSV G protein that do not exhibit strong PS binding.

Although RABV G protein can also bind efficiently to PS [13,16,17], several proteins have been suggested as the receptors for RABV, including the muscular form of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (NAch R), neurotrophin receptor p75NTR and neural cell-adhesion molecule (NCAM) [18]. NAch R was first identified as a potential RABV receptor by in vivo colocalization of the virus and itself in mouse diaphragms and cultured chick myotubes [19]. In addition, pretreatment of mytotubes with α-bungarotoxin and d-tubocurarine, both antagonists of the acetylcholine receptor, subsequently reduced infection of the myotubes with RABV. The identification of sequence homology between RABV G and snake-venom curaremimetic neurotoxins, as well as experiments demonstrating binding between synthetic peptides of both the G protein and snake-venom neurotoxins to the α-subunit of the NAch R, further support NAch R as a receptor for RABV [19-22]. However, it has been shown that most laboratory cell lines can be infected with RABV despite the absence of NAch R, and that treatment of these cell lines with α-bungarotoxin does not decrease RABV infection [23], indicating that other receptors can mediate virus entry, at least in cell culture systems.

Neurotrophin receptor p75NTR was identified as a RABV receptor using a cDNA expression library from neuroblastoma cells [24]. Transfection of the mouse homolog of neurotrophin receptor p75NTR was found to confer binding of soluble RABV G protein. In addition, BSR cells, which are usually nonpermissive to field isolates of RABV, could be infected after transfection with the neurotrophin receptor [24]. However, it has been found that mice lacking p75NTR can be infected with RABV, and that mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons expressing the receptor cannot be infected with RABV [25]. Finally, the candidate receptor NCAM was identified by a survey of susceptible and resistant cell lines [26]. Not only does the degree of expression of NCAM on the surface of the cell directly correlate with susceptibility to RABV infection, but soluble NCAM and blocking cell-surface NCAM decrease infection. In addition, resistant L cells transfected with NCAM become permissive to RABV infection. In vivo, however, mice lacking NCAM still die from RABV infection, but at a delayed rate when compared with wild-type mice. The possible reason for having multiple receptors identified for RABV can be partially explained by the hypothesis that RABV may sequentially use different receptors during viral infection in the mammalian nervous system [18]. Owing to the fact that RABV specifically invades and infects the mammalian nervous system, viral vectors pseudotyped with the RABV G protein and the short peptide corresponding to RABV G protein-receptor binding site have proven to be promising in targeting therapeutic molecules across the blood–brain barrier for treatment of neurological disease [22]. In the future, structure-based G-protein engineering for improving drug-delivery efficiency and sp ecificity will continue to be of interest.

In the case of VHSV G protein, a proteinaceous receptor is also likely to be involved in virus entry. Despite its strong binding to PS, studies with inhibitory monoclonal antibodies have identified fibronectin as a VHSV receptor on fish cells [27].

Endocytosis of VSV

Although the receptor for VSV remains elusive, the role of endocytosis and low pH-induced fusion in the endosomal vesicles for viral infection has been well established [28]. Upon initial binding on the cell surface, VSV is internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis and the virus is transported into endosomal compartments, where the virus fuses and releases its genome into the cytosol to initiate replication. Despite multiple endocytic pathways that are available in host cells, VSV appears to specifically utilize a clathrin-mediated endocytic route to enter into cells, in contrast to the multiple entry pathways utilized by influenza virus [29]. In early studies relying on electron microscopy, VSV was found in coated pits or vesicles [30], although viruses in noncoated pits were also observed by different research groups [31]. Studies examining the entry pathway of VSV or VSV G protein-pseudotyped retroviral particles using molecular biological or pharmacological approaches found that the entry of VSV and VSV G protein-pseudotyped retroviral particles was greatly inhibited by s iRNAs targeting clathrin heavy chain and also by chlorpromazine, a drug that specifically blocks clathrin-mediated endocytosis [32,33]. Recently, it has been shown that while VSV takes a clathrin- and dynamin-dependent route of entry, the classical adaptor protein AP-2 was not required for infection [34]. Time-lapse microscopy demonstrated the virus entering either preformed clathrincoated pits or formed pits de novo. A mechanism has also recently been proposed by which VSV can enter cells through vesicles that are incompletely coated with clathrin. This mechanism relies on the nucleation of clathrin rather than depending on random capture of clathrin-coated pits, and depends on actin for internalization [35]. Ultimately, the means by which VSV particles are exclusively sorted into clathrin-coated pits has yet to be defined, and this is in part due to the apparent absence of a specific receptor.

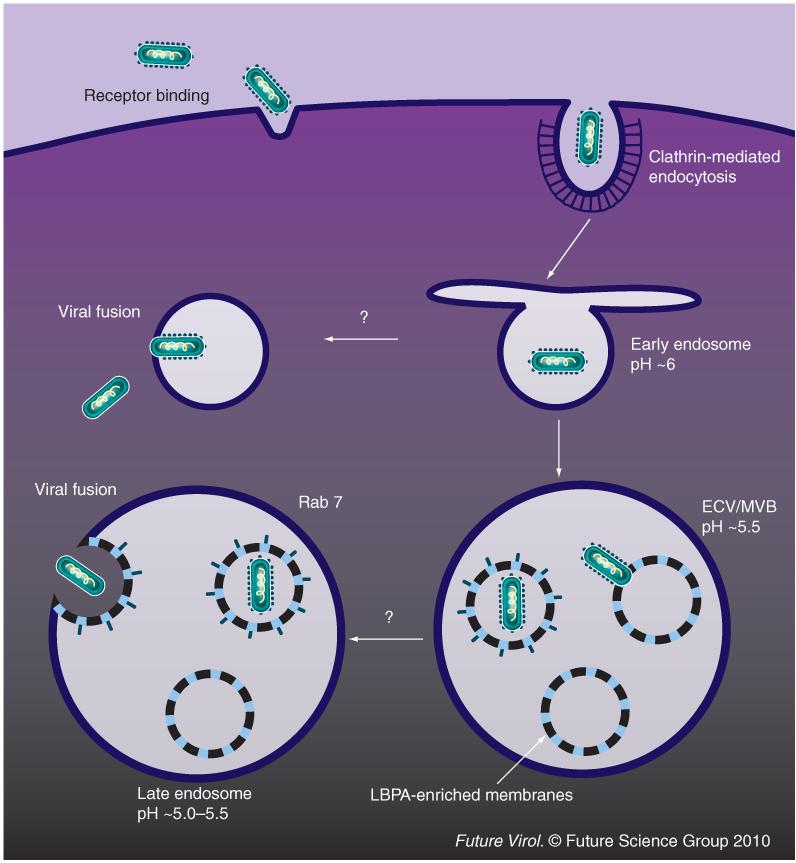

Fusion mediated by VSV G occurs over a wide pH range, from pH 6.2 to 5.0 [36,37]; there-fore, various endosomal compartments including early endosomes (pH ~6.2) and late endosomes (pH ~5.5–5.0) are potentially suitable for VSV fusion [38]. Dominant-negative forms of Rab GTPases were used to study the requirements for endocytic Rabs in viral trafficking. A Rab5 mutant that blocks maturation of plasma membrane-derived vesicles to early endosomes inhibited VSV infection, whereas a Rab7 mutant that blocks trafficking from early endosomes to late endosomes had no significant effect on viral infectivity, indicating that VSV fusion might occur before viral-containing vesicles mature into late endosomes [39]. It was shown by tracking fluorescently labeled viral particles in live baby hamster kidney cells that most fusion events for VSV occurred in the intraluminal vesicles (ILV) of endosomal transport intermediates, termed multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with an approximate pH of 5.5 [40]. However, this finding has been disputed, based on the rapid kinetics of fusion seen in HeLa cells (half-life of 2–3 min) [34]. By contrast, fusion in baby hamster kidney cells was reported to occur over a much longer time scale of 20–25 min [40]. The wide pH range for VSV fusion, as well as differences in endosome composition, might explain the discrepancy in the location for VSV fusion as described earlier. Rab7 mutants blocking traffic from the early-to-late endosome may force the virus to fuse in the early endosome. The preference for fusion in ILVs of MVBs might be due to the abundance of inner membranes as compared with the limiting outer membranes, or owing to the relatively low pH found in MVBs as compared with the pH of the early endosome. This preferential fusion could also be related to the existence of specific lipid components found within ILVs. Semliki Forest virus has a similar pH fusion range and appears to preferentially fuse in the early endosome [36,41]; the abundance of cholesterol in the early endosome may contribute to this preferential fusion event [42]. It has been shown that an unusual lipid, lysobisphosphatidic acid (LBPA), accumulates in the ILVs of MVBs and while anti-LBPA antibodies do not appear to block the fusion event itself, it remains possible that specific lipid components such as LBPA might control the VSV fusion r eaction in endosomes [43].

Fusion of the virus envelope with ILVs would result in delivery of viral RNPs into the lumen of internal vesicles; the viral RNPs would then travel along with the maturing MVB into late endosomes, with back-fusion of internal VSV-containing vesicles and the late endosomal membrane releasing viral RNPs into the cytoplasm for replication. It is believed that continuous travel in the endosomal intermediates after fusion may benefit virus navigation towards the perinuclear region of the cell. Consistent with the sequential events of fusion and RNP release into the cytosol, the putative LBPA effectors Alix and PtdIns(3)P-binding protein SNX16, known to regulate invagination of inner vesicles in MVBs and back-fusion of the inner membrane with the outer membrane, can specifically affect RNP delivery, but not fusion (Figure 1). Currently, VSV is the only virus that has been suggested to traffic through MVBs and fuse with their internal membrane during entry. However, sorting through MVBs has been widely used by other cell ligands and toxins [44].

Figure 1. Route of vesicular stomatitis virus entry into host cells.

After receptor binding, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. During the maturation of VSV-containing endosomes, VSV fuses with intraluminal vesicles of intermediate endosomes. The subsequent back-fusion of intraluminal vesicles with the outer membrane of multivesicular late endosomes leads to the cytoplasmic delivery of viral ribonucleoprotein. ECV: Endosomal carrier vesicle; LBPA: Lysobisphosphatidic acid; MVB: Multivesicular body.

Membrane fusion mediated by G protein

Fusion domain(s) of the G protein

Prior to the determination of its x-ray crystallographic structure, identification of the fusion peptide in the G protein was difficult owing to the lack of an obvious stretch of suitable residues in its primary sequence. In early studies, membranes were labeled with photoactive reagents in order to probe amino acid residues that were inserted into the membrane during G protein-mediated fusion. Long stretches of protein were labeled, ranging from amino acids 59 to 221(42–205) for VSV and 103 to 179 for RABV [45]. Meanwhile, previous studies relying on mutagenesis to locate the fusion peptide also failed to provide definitive results and several regions were described to be able to modulate fusogenic activity of the G protein. For instance, amino acids 118–139(102–123) were previously considered to constitute an internal fusion peptide based on the fact that intro duction of a glyco sylation site upstream of this region abolished fusion; this region is rich in apolar residues and is conserved in vesiculoviruses [46]. Mutagenesis studies in this region have shown that the mutations G124(108)E, P127(111)D and A133(117)K either altered or abolished low pH-dependent membrane fusion activity, as measured by a syncytia formation assay [47]. Other mutations in this region, such as F125(109)Y and D137(121)N, shifted the optimal pH of G protein mediated cell–cell fusion [48]. However, mutations at other conserved regions, for example, amino acids 181–212(165–196) and 395–418(379–402) located near the carboxyl terminus, could also affect protein fusion [49,50]. Although the aforementioned results shed light on the architecture of G protein fusion machinery, mutagenesis studies in the absence of a high-resolution protein structure may not identify the true viral fusion peptide; however, they may instead recognize amino acids or regions involved in protein conformational changes during the fusion event or those which are involved in stabilizing trimer organization.

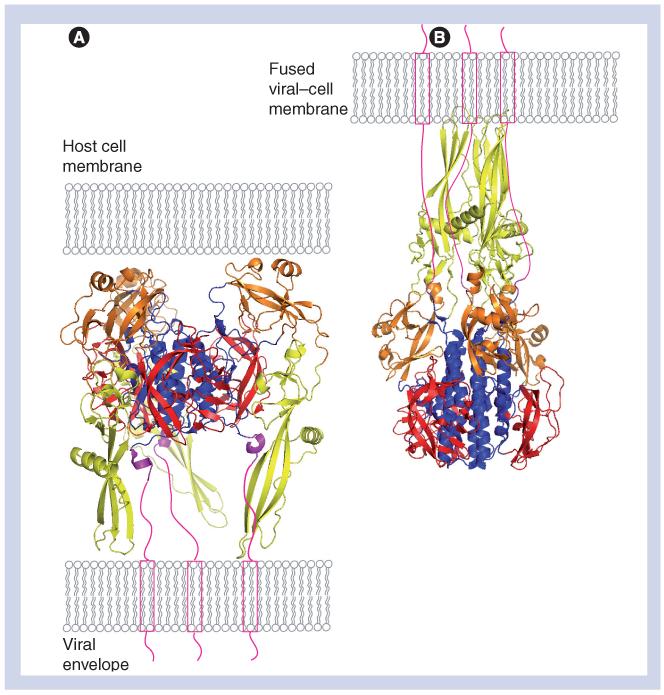

The recently solved crystal structures of the ectodomain of VSV G (comprising amino acids 1–410), in both pre- and postfusion forms, are a breakthrough in terms of understanding the fusion mechanism mediated by the G protein. The overall structure of VSV G in the low pH form does not resemble any well-known viral fusion protein, although some structural elements can be found within both class I and II viral fusion proteins (Figure 2) [51]. Each monomer in the VSV G protein trimer folds into four distinct domains: lateral domain I at the top of the molecule; domain II, which is responsible for trimerization; domain III, a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain; and domain IV, which is believed to be the fusion domain [52]. In the low pH form, the G-protein trimer has a central coiled–coil, which is characteristic of a class I fusion protein. However, the fusion peptide is not located at the amino terminus of the molecule and exposed after proteolytic cleavage, which is often the case in class I fusion proteins, but instead, is located in the internal loop region that is a common feature of class II fusion proteins [53]. Nevertheless, in contrast to the one continuous internal fusion loop found in class II fusion proteins, the fusion loops in VSV G protein are bipartite. Each monomer exposes two fusion loops, each located at the tip of an extended β-strand. Along with other structural features, the fusion loop organization suggests that VSV G protein is neither a class I nor a class II viral fusion protein, but instead, should be regarded as a class III viral fusion protein. Surprisingly, the crystal structures of herpes simplex virus-1 G protein B and the baculovirus fusion protein gp64 are shown to have a very similar protein fold and secondary structure to the G protein in the postfusion form, indicating that they may have a common evolutionary origin [54-57].

Figure 2. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein structure in pre- and postfusion conformations.

(A) VSV G protein in its prefusion form (protein databank [PDB] accession number 2j6j). (B) VSV G protein in its postfusion form (PDB accession number 2cmz). To demonstrate the orientation of the molecules, the viral membrane is depicted in cartoon form, and the carboxyl terminus of G protein unsolved in the crystal structure(s) (amino acids 414–495) is depicted in green. In (B), the final fused membrane with inserted fusion loops and the transmembrane domain is shown to illustrate the orientation of the molecules after pH-induced conformational changes. The structural domains of VSV G are labeled in different colors, with domain I in red, domain II in blue, domain III (PH domain) in orange, domain IV (fusion domain) in yellow and the carboxyl terminal part of the G protein (amino acids 406–413) in magenta. The structures of the VSV G protein ectodomain were generated with PyMOL software (DeLano Scientific) and transferred to Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

G protein: Glycoprotein; VSV: Vesicular stomatitis virus.

There are four hydrophobic residues found within the proposed bipartite fusion loops; W72 and Y73 in loop I, and Y116 and A117 in loop II. In the postfusion form, these four hydrophobic residues are exposed and located at the same end of the molecule as the carboxyl terminus of the membrane anchor region. Sequence alignment of other rhabdovirus family G proteins reveals that these hydrophobic residues are conserved, and an aromatic residue (W, F or Y), in combination with one or more different apolar residues, is found within one of the two fusion loops [51,58,59]. The VSV G protein fusion loops are bowl-like or concave in shape, which is a feature shared by the loop region of the class II fusion proteins. The crystal structure of dengue virus envelope (E) protein, a class II fusion protein, identified three conserved hydrophobic residues – W101, L107 and F108 – located at the tip of the internal loop. These residues are fully exposed at the bottom of the E protein fusion-loop bowl and are thought to anchor the protein to the target membrane [60]. However, the existence of charged residues at the outer rim of the fusion-loop bowl of VSV G and dengue virus E protein sets an upper limit for the depth of penetration of the fusion loop, of approximately 8.5 Å into the outer leaflet membrane for VSV G protein and 6 Å for dengue virus E protein [51,60]. Despite the relatively shallow penetration mediated by the internal fusion loops compared with that mediated by the fusion peptide of influenza hemagglutinin, which was shown to penetrate 16 Å deep into the outer membrane leaflet with a 20 amino acidlong helix [61], the fusogenic activity of proteins with internal fusion loops is still highly efficient, based on the fact that the class II viral fusion protein E of flavivirus exhibits the fastest and most efficient fusion machinery of all enveloped viruses analyzed to date [62].

With the high-resolution structures of VSV G protein in hand, we can now better understand how the previously identified amino acids or regions shown by mutagenesis to be important for fusion actually modulate the fusogenic activity of the G protein, even though these residues or regions might not be in the bipartite fusion loops. The previously proposed fusion peptide – amino acids 118–139(102–123) for VSV G protein – in which the mutations at residues G124(108), F125(109) and P127(111) affect G protein-mediated fusion activity, is located in the trimer interface and is responsible for the stabilization of the fusion domain in the low-pH form. The other region comprising residues 181–212(165–196), in which the mutations showed fusion defects in cell–cell fusion assays, is the hinge region between domain III and fusion domain IV, and is involved in repositioning the fusion domain to the top of the molecule during conformational changes of the G protein from pre- to postfusion states. The carboxyl terminal region, including amino acids 395–418(379–402) that has been shown to have an effect on the fusion activity of VSV G protein, is located in the short helices of the six-helix bundle and is responsible for stabilization of G-protein trimers. A systematic mutagenesis study has recently shown that the proposed bipartite fusion loops of VSV G protein are functional, with W72 being the most critical residue for fusion [58]. As evaluated by cell–cell fusion and G protein-pseudotyped retrovirus infection assays, W72 could only tolerate mutation to an F residue, and Y73 and 116 could be mutated to other aromatic residues but not alanine or valine. By contrast, A117 could be substituted with a variety of amino acids, except for basic residues [58].

Examination of the two major VSV serotypes (Indiana and New Jersey) reveals differences in the fusion loops, with the New Jersey G protein having a glycine at position 117. Biological differences in fusion between VSV Indiana and New Jersey indicate that the G protein of VSV New Jersey activates membrane fusion at lower pH than the G protein of VSV Indiana [63]. Selection of mutant VSV Indiana viruses by growth at successively lower pH values resulted in a single point mutation in the G protein – F18(2)L – as well as other mutations; specifically, H65(49)R, Q301(285)R and K462(446)R, in areas not previously implicated in attachment or fusion [63].

In the case of VHSV, the structure of the G protein has been analyzed in the context of viral pathogenicity. Two VHSV virulence regions were identified using attenuated laboratory strains and avirulent VHSV mutants [64]. These studies allowed Gaudin et al. to propose the existence of a bipartite fusion loop connected by a disulfide bridge between cysteines 110 and 152 – a prediction confirmed with the solving of the 3D structure of VSV G protein and modeling of the VHSV sequence [51]. Based on sequence alignment and structural modeling, the residues in the bipartite fusion loops for the VHSV G protein, including F115 and W154, have also been shown to be critical for fusion [65]. Fusion studies involving virulent and attenuated strains of VHSV have demonstrated that more virulent strains undergo membrane fusion at a near-neutral pH as compared with attenuated strains, which require a more acidic pH [64].

Reversible conformational change of the G protein

Based on evidence from studies using electron microscopy, monoclonal-antibody binding and protease-cleavage assays, it has been described that the G protein can assume at least three d ifferent states:

-

■

The native (N) state detected at the viral s urface at a neutral pH;

-

■

The active (A) state, in which the G protein becomes more hydrophobic and acquires the ability to interact with the target membrane;

-

■

The fusion inactive (I) state, which results from the longer period of incubation in an acidic pH environment [66,67].

However, G proteins in the I state are not denatured; the protein can revert to the N state by readjusting the pH back to neutral. G protein properties in different states have been studied extensively in RABV. Electron-microscopy studies have shown that the RABV G protein remains in the I state for a longer period of time than in the N state, and that the I state is sensitive to protease cleavage, suggesting it is morphologically and antigentically distinct from the N state [66]. By contrast, the A state is hydrophobic, triggering viral aggregation, but is very similar to the N state in morphology and antigenicity, with its stability depending on both pH and temperature [68]. Overall, the G protein appears to exist in different states in a pH-dependent equilibrium. A monoclonal antibody specifically recognizing the I state of RABV G protein could bind to the virion at a neutral pH after a long period of incubation and, by sequestering the G protein in the I state, could drive equilibrium toward the I state [69]. Likewise, a monoclonal antibody specifically recognizing the N form could shift the equilibrium to the N state at pH 6.25, a pH at which fusion is clearly detectable [70]. It was also confirmed by electron microscopy that both the N and I forms could be visualized when the virions were incubated at a pH above pH 6.4 for 2 h at 37 °C, and nearly equal amounts of both forms were produced at pH 6.7 [68]. The existence of G protein in equilibrium between different states is in striking contrast to most other known viral fusion proteins, which are metastable and undergo irreversible conformational change from pre- to postfusion states.

The reversibility of G protein in the transition between states is necessary for its transport through the secretory pathway. G protein is primed for conformational change once it oligomerizes into a trimer in the endoplasmic reticulum. The Golgi apparatus typically has a pH of approximately 6.2, and post-Golgi vesicles most likely have a lower pH (possibly as low as pH 5.8) [71], which means that the G protein is not expected to be in the N state during secretion. Indeed, a previous study has shown the existence of G proteins in the I state within secretory vesicles; therefore, it avoids unnecessary fusion and refolds back to the N state at the plasma membrane [72]. Moreover, because it is reversible, the energy released during transition from the N state to the A or the I state is quite limited and it is believed that the G protein requires at least 13–19 trimers to overcome the energy barrier in order to destabilize the target membrane and initiate fusion pore formation [70].

The availability of crystal structures has also shed light on the reversible conformations adopted by the G protein. Protonation of histidines in both class I and II fusion proteins is suggested to be the trigger for conformational change upon exposure to low pH [73]; it also appears to be important for conformational rearrangement of the G protein from the pre- to the postfusion form [74]. It has been predicted from crystal structures of VSV G protein that neither the prefusion form of G protein at low pH, nor its postfusion form at neutral or higher pH, is a stable structure, and tends to undergo conformational rearrangements to return to its original state. In the prefusion form, H407 and P408 in the C-terminal region and H162, H60 and S84 from the fusion domain are clustered together and uncharged at neutral pH; protonation of these residues at acidic pH provides a repulsive force to destabilize the interaction of the fusion domain and C-terminal region, resulting in the movement of the fusion domain toward the target membrane [52]. In the postfusion form, a large number of acidic amino acids, for example, D268, D274, D395, E276 and D393, are clustered together in domain II and the deprotonation of these residues at neutral or higher pH induces strong repulsive forces that destabilize the G protein trimer interaction [52]. Moreover, the deprotonation of histidines 132 and 407 at higher pH values weakens the interactions in the fusion domains, as well as the interaction between the fusion domain and the C-terminus of G-protein molecule [52]. The protonation of histidine 132(116) has been experimentally shown to be essential for VSV G-mediated fusion, whereas alanine substitution abolished fusogenic activity [74].

Role of the membrane-proximal & transmembrane domains in G protein-mediated membrane fusion

The membrane-proximal regions of the ectodomains from a variety of viral G proteins including VSV G protein, HIV gp41, parainfluenza virus F protein and SARS-coronavirus S protein have been shown to have the ability to modulate viral fusion [75]. As shown for HIV-1 G proteins [76], the sequence ana lysis at the membrane-proximal domains reveals regions that are rich in aromatic residues, which are commonly seen in the membrane protein–lipid bilayer interface. It is hypothesized that the membrane-proximal region might interact with the fusion peptide proximal segment to stabilize the membrane-interactive end of the trimer hairpins [77]. For VSV G protein, the deletion of the last 13 amino acids in the ectodomain; that is, N449(433)–W461(445) dramatically reduced cell–cell fusion activity and viral infectivity [78] and the insertion of a three amino acid linker at positions 410(394) and 415(399) abolished membrane fusion [49]. However, the double mutation of G131(115)A and G404(388) A, which are adjacent to the fusion loop II and the membrane-proximal region, was more fusogenic than the two individual mutations alone, suggesting that these two regions might act synergistically during viral fusion [79]. However, in contrast to HIV gp41 [76], the conserved aromatic residues in VSV G protein appear not to be important for fusion [78]. In addition, the membrane-proximal region of VSV G protein, consisting of only 14 ectodomain amino acids, along with the transmembrane (TM) and intracellular domains, can induce hemifusion, function as a membrane fusion potentiator and also promote the fusion activity of an unrelated G protein – indicating that this region alone may be able to bend the membrane during the fusion reaction [80].

Similar to other well-studied viral fusion proteins, the TM and cytoplasmic domains of VSV G protein play an essential role in fusion pore formation and enlargement during the fusion process [81-83]. Replacing the TM domain of the G protein with a glycerophosphatidylinositol moiety, which only anchored the protein into the external leaflet of the membrane bilayer, completely abolished G-protein fusogenic activity, whereas replacing the TM with domains from foreign integral membrane proteins only partially reduced fusion as measured by a cell–cell fusion assay. This suggested that simply spanning the lipid bilayer with a hydrophobic peptide sequence, but not the specific peptide sequence itself, was sufficient for fusion [83]. However, glycine residues in the TM domain of the G protein do appear to be crucial for fusion, since deletion of six internal residues, including two glycines, abolishes syncytia-forming ability. The reintroduction of a glycine residue into the deletion mutant can partially recover fusion activity [84,85]. It has been suggested that glycine residues may destabilize the α-helices, which are observed in most TM domains of integral membrane proteins, with helix bending by the glycine residue possibly destabilizing the hemifusion diaphragm and promoting fusion pore formation [84].

Within the cytoplasmic tail of the G protein, certain rhabdoviruses are post-translationally modified by the addition of palmitic acid moieties on individual cysteine residues. Such viruses include VSV Indiana and RABV [82-85]. Expression of VSV Indiana G protein containing a cysteine–serine point mutation in the cytoplasmic tail was shown to have no obvious defect in low pH-induced membrane fusion and no effect on the titer of rescued virus [86], and other viruses (i.e., VSV New Jersey) are not palmitoylated. Therefore, G palmitoylation of VSV is not considered to play an essential role in virus fusion or budding. It has been suggested that palmitoylation of RABV G protein may aid in stabilizing the protein within the virus envelope and may also be involved in virus budding [84].

Future perspective

Although VSV, RABV and other rhabdoviruses have been extensively studied for decades, recent findings on the molecular mechanism underlying the viral lifecycle have challenged our previous understanding of these viruses, and they have turned out to not be as ‘simple’ as originally thought. As VSV has continued to show promise as a delivery vector in gene therapy, a better understanding of rhabdovirus entry will help us design vectors with controlled tropism and fusion activity. With the recently determined crystal structures for VSV G, we are now better equipped to characterize the receptor-binding sites for VSV, which may eventually help us identify receptors and develop pharmacological inhibitors that efficiently block the entry of VSV and other rhabdoviruses.

Executive summary.

-

■

Rhabdovirus entry is controlled by the viral glycoprotein (G protein), a class III viral fusion protein.

-

■

For the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), the receptor is ubiquitous, but unknown, and virus enters cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, with fusion occurring with endosomes at a pH of approximately 5.8. The rabies virus uses more specific proteinaceous receptor(s).

-

■

The conformational rearrangements involved in G protein-mediated membrane fusion are reversible, unlike other well-characterized viral fusion proteins. Crystal structures of VSV G protein in pre- and postfusions states may help elucidate the mechanisms underlying the changes in the conformational states.

-

■

Critical residues of the G protein involved in membrane fusion lie within the bipartite fusion loops and adjacent to the transmembrane region.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ruth Collins, Holger Sondermann, Lois Pollack, Susan Daniel and Brian Crane for helpful advice during the preparation of this article.

Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported in part by the Cornell University Nanobiotechnology Center (NBTC) – an STC program of the National Science Foundation under agreement number ECS-987677, and the NIH (NIAID).

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xiangjie Sun, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA, Tel.: +1 607 253 4020, Fax: +1 607 253 3384.

Shoshannah L Roth, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA, Tel.: +1 607 253 4020, Fax: +1 607 253 3384.

Michele A Bialecki, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA, Tel.: +1 607 253 4020, Fax: +1 607 253 3384.

Gary R Whittaker, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.Lyles DS, Rupprecht CE. Rhabdoviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott Williams; Wilkins, PA, USA: 2007. pp. 1363–1408. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann B, Beer M, Schutze H, Mettenleiter TC. Fish rhabdoviruses: molecular epidemiology and evolution. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;292:81–117. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27485-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawson ND, Stillman EA, Whitt MA, Rose JK. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses from DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92(10):4477–4481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schloemer RH, Wagner RR. Cellular adsorption function of the sialoglycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus and its neuraminic acid. J. Virol. 1975;15(4):882–893. doi: 10.1128/jvi.15.4.882-893.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlegel R, Willingham MC, Pastan IH. Saturable binding sites for vesicular stomatitis virus on the surface of vero cells. J. Virol. 1982;43(3):871–875. doi: 10.1128/jvi.43.3.871-875.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlegel R, Tralka TS, Willingham MC, Pastan I. Inhibition of VSV binding and infectivity by phosphatidylserine: is phosphatidylserine a VSV-binding site? Cell. 1983;32(2):639–646. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90483-x. ■ Original study suggesting that phosphatidylserine is a receptor for vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV).

- 7.Seganti L, Superti F, Girmenia C, Melucci L, Orsi N. Study of receptors for vesicular stomatitis virus in vertebrate and invertebrate cells. Microbiologica. 1986;9(3):259–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coil DA, Miller AD. Phosphatidylserine is not the cell surface receptor for vesicular stomatitis virus. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):10920–10926. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10920-10926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boon JM, Smith BD. Chemical control of phospholipid distribution across bilayer membranes. Med. Res. Rev. 2002;22(3):251–281. doi: 10.1002/med.10009. ■ Concludes that phosphatidylserine is not the receptor for VSV.

- 10.Estepa AM, Rocha AI, Mas V, et al. A protein G fragment from the salmonid viral hemorrhagic septicemia rhabdovirus induces cell-to-cell fusion and membrane phosphatidylserine translocation at low pH. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(49):46268–46275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estepa A, Coll JM. Pepscan mapping and fusion-related properties of the major phosphatidylserine-binding domain of the glycoprotein of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus, a salmonid rhabdovirus. Virology. 1996;216(1):60–70. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunez E, Fernandez AM, Estepa A, Gonzalez-Ros JM, Gavilanes F, Coll JM. Phospholipid interactions of a peptide from the fusion-related domain of the glycoprotein of VHSV, a fish rhabdovirus. Virology. 1998;243(2):322–330. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coll JM. Synthetic peptides from the heptad repeats of the glycoproteins of rabies, vesicular stomatitis and fish rhabdoviruses bind phosphatidylserine. Arch. Virol. 1997;142(10):2089–2097. doi: 10.1007/s007050050227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carneiro FA, Lapido-Loureiro PA, Cordo SM, et al. Probing the interaction between vesicular stomatitis virus and phosphatidylserine. Eur. Biophys. J. 2006;35(2):145–154. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0012-z. ■ In-depth biophysical study on the binding properties of VSV glycoprotein (G protein) to phosphatidylserine.

- 15.Hall MP, Burson KK, Huestis WH. Interactions of a vesicular stomatitis virus G protein fragment with phosphatidylserine: NMR and fluorescence studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1415(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Superti F, Seganti L, Tsiang H, Orsi N. Role of phospholipids in rhabdovirus attachment to CER cells. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 1984;81(3-4):321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01310002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wunner WH, Reagan KJ, Koprowski H. Characterization of saturable binding sites for rabies virus. J. Virol. 1984;50(3):691–697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.3.691-697.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lafon M. Rabies virus receptors. J. Neurovirol. 2005;11(1):82–87. doi: 10.1080/13550280590900427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lentz Tl, Burrage TG, Smith AL, Crick J, Tignor GH. Is the acetylcholine-receptor a rabies virus receptor. Science. 1982;215(4529):182–184. doi: 10.1126/science.7053569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lentz TL, Hawrot E, Wilson PT. Synthetic peptides corresponding to sequences of snake-venom neurotoxins and rabies virus glycoprotein bind to the nicotinic acetylcholinereceptor. Proteins. 1987;2(4):298–307. doi: 10.1002/prot.340020406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lentz TL, Wilson PT, Hawrot E, Speicher DW. Amino acid sequence similarity between rabies virus glycoprotein and snake venom curaremimetic neurotoxins. Science. 1984;226(4676):847–848. doi: 10.1126/science.6494916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Wu H, Mcbride JL, et al. Transvascular delivery of small interfering RNA to the central nervous system. Nature. 2007;448(7149):39–43. doi: 10.1038/nature05901. ■ Demonstrates a novel approach of using short peptide derived from rabies virus G protein as a carrier to specifically deliver siRNA into the CNS.

- 23.Reagan KJ, Wunner WH. Rabies virus interaction with various cell-lines is independent of the acetylcholine-receptor – brief report. Arch. Virol. 1985;84(3-4):277–282. doi: 10.1007/BF01378980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuffereau C, Benejean J, Blondel D, Kieffer B, Flamand A. Low-affinity nerve-growth factor receptor (p75NTR) can serve as a receptor for rabies virus. EMBO J. 1998;17(24):7250–7259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuffereau C, Schmidt K, Langevin C, Lafay F, Dechant G, Koltzenburg M. The rabies virus glycoprotein receptor p75NTR is not essential for rabies virus infection. J. Virol. 2007;81(24):13622–13630. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02368-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thoulouze MI, Lafage M, Schachner M, Hartmann U, Cremer H, Lafon M. The neural cell adhesion molecule is a receptor for rabies virus. J. Virol. 1998;72(9):7181–7190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7181-7190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bearzotti M, Delmas B, Lamoureux A, Loustau AM, Chilmonczyk S, Bremont M. Fish rhabdovirus cell entry is mediated by fibronectin. J. Virol. 1999;73(9):7703–7709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7703-7709.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matlin KS, Reggio H, Helenius A, Simons K. Pathway of vesicular stomatitis virus entry leading to infection. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;156(3):609–631. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Influenza virus can enter and infect cells in the absence of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 2002;76(20):10455–10464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10455-10464.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Superti F, Seganti L, Ruggeri FM, Tinari A, Donelli G, Orsi N. Entry pathway of vesicular stomatitis virus into different host cells. J. Gen. Virol. 1987;68(Pt 2):387–399. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-2-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cernescu C, Constantinescu SN, Popescu LM. Electron microscopic observations of vesicular stomatitis virus particles penetration in human fibroblasts. Rev. Roum. Virol. 1990;41(2):93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchard E, Belouzard S, Goueslain L, et al. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 2006;80(14):6964–6972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun X, Yau VK, Briggs BJ, Whittaker GR. Role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis during vesicular stomatitis virus entry into host cells. Virology. 2005;338(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johannsdottir HK, Mancini R, Kartenbeck J, Amato L, Helenius A. Host cell factors and functions involved in vesicular stomatitis virus entry. J. Virol. 2008;83(1):440–453. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01864-08. ■■ Excellent comprehensive study on VSV entry kinetics and cellular factors required. However, their results dispute two-step fusion events described in [40].

- 35.Cureton DK, Massol RH, Saffarian S, Kirchhausen TL, Whelan SP. Vesicular stomatitis virus enters cells through vesicles incompletely coated with clathrin that depend upon actin for internalization. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(4):e1000394. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White J, Matlin K, Helenius A. Cell fusion by Semliki Forest, influenza, and vesicular stomatitis viruses. J. Cell Biol. 1981;89(3):674–679. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.3.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fredericksen BL, Whitt MA. Mutations at two conserved acidic amino acids in the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus affect pH-dependent conformational changes and reduce the pH threshold for membrane fusion. Virology. 1996;217(1):49–57. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Der Goot FG, Gruenberg J. Intraendosomal membrane traffic. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16(10):514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sieczkarski SB, Whittaker GR. Differential requirements of rab5 and rab7 for endocytosis of influenza and other enveloped viruses. Traffic. 2003;4:333–343. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Blanc I, Luyet PP, Pons V, et al. Endosome- to-cytosol transport of viral nucleocapsids. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(7):653–664. doi: 10.1038/ncb1269. ■■ By using time-lapse microscopy and cell biological approaches, the author demonstrated that the VSV viral fusion with endosomal membranes and nucleocapsid release occur at two sequential steps.

- 41.Pelkmans L, Helenius A. Insider information: what viruses tell us about endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15(4):414–422. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi T, Yamaji-Hasegawa A, Kiyokawa E. Lipid domains in the endocytic pathway. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;12(2):173–182. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piper RC, Katzmann DJ. Biogenesis and function of multivesicular bodies. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:519–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uchil P, Mothes W. Viral entry: a detour through multivesicular bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7(7):641–642. doi: 10.1038/ncb0705-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durrer P, Gaudin Y, Ruigrok RW, Graf R, Brunner J. Photolabeling identifies a putative fusion domain in the envelope glycoprotein of rabies and vesicular stomatitis viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270(29):17575–17581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitt MA, Zagouras P, Crise B, Rose JK. A fusion-defective mutant of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1990;64(10):4907–4913. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4907-4913.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fredericksen BL, Whitt MA. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein mutations that affect membrane fusion activity and abolish virus infectivity. J. Virol. 1995;69(3):1435–1443. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1435-1443.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Ghosh HP. Characterization of the putative fusogenic domain in vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. J. Virol. 1994;68(4):2186–2193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2186-2193.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, Drone C, Sat E, Ghosh HP. Mutational ana lysis of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G for membrane fusion domains. J. Virol. 1993;67(7):4070–4077. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4070-4077.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shokralla S, He Y, Wanas E, Ghosh HP. Mutations in a carboxy-terminal region of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G that affect membrane fusion activity. Virology. 1998;242(1):39–50. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roche S, Bressanelli S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y. Crystal structure of the low-pH form of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. Science. 2006;313(5784):187–191. doi: 10.1126/science.1127683. ■■ First report of VSV G protein crystal structure in post-fusion form. This is also the only available postfusion structure of a class III viral fusion protein.

- 52.Roche S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y, Bressanelli S. Structure of the prefusion form of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. Science. 2007;315(5813):843–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1135710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schibli DJ, Weissenhorn W. Class I and class II viral fusion protein structures reveal similar principles in membrane fusion. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2004;21(6):361–371. doi: 10.1080/09687860400017784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15(7):690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kadlec J, Loureiro S, Abrescia NG, Stuart DI, Jones IM. The postfusion structure of baculovirus gp64 supports a unified view of viral fusion machines. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15(10):1024–1030. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heldwein EE, Lou H, Bender FC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science. 2006;313(5784):217–220. doi: 10.1126/science.1126548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roche S, Albertini AA, Lepault J, Bressanelli S, Gaudin Y. Structures of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein: membrane fusion revisited. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65(11):1416–428. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7534-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun X, Belouzard S, Whittaker GR. Molecular architecture of the bipartite fusion loops of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G, a class III viral fusion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(10):6418–6427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker Pj, Kongsuwan K. Deduced structural model for animal rhabdovirus glycoproteins. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80(Pt 5):1211–1220. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature. 2004;427(6972):313–319. doi: 10.1038/nature02165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han X, Bushweller JH, Cafiso DS, Tamm LK. Membrane structure and fusion-triggering conformational change of the fusion domain from influenza hemagglutinin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8(8):715–720. doi: 10.1038/90434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stiasny K, Heinz FX. Flavivirus membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87(Pt 10):2755–2766. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez I, Wertz GW. Biological differences between vesicular stomatitis virus indiana and new jersey serotype glycoproteins: Identification of amino acid residues modulating pH-dependent infectivity. J. Virol. 2005;79(6):3578–3585. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3578-3585.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gaudin Y, De Kinkelin P, Benmansour A. Mutations in the glycoprotein of viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus that affect virulence for fish and the pH threshold for membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80(Pt 5):1221–1229. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1221. ■ First suggestion that the G protein has a bipartite fusion peptide.

- 65.Rocha A, Ruiz S, Tafalla C, Coll JM. Conformation- and fusion-defective mutations in the hypothetical phospholipid-binding and fusion peptides of viral hemorrhagic septicemia salmonid rhabdovirus protein G. J. Virol. 2004;78(17):9115–9122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9115-9122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gaudin Y, Tuffereau C, Segretain D, Knossow M, Flamand A. Reversible conformational changes and fusion activity of rabies virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 1991;65(9):4853–4859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4853-4859.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clague MJ, Schoch C, Zech L, Blumenthal R. Gating kinetics of pH-activated membrane fusion of vesicular stomatitis virus with cells: stopped-flow measurements by dequenching of octadecylrhodamine fluorescence. Biochemistry. 1990;29(5):1303–1308. doi: 10.1021/bi00457a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gaudin Y, Ruigrok RW, Knossow M, Flamand A. Low-pH conformational changes of rabies virus glycoprotein and their role in membrane fusion. J. Virol. 1993;67(3):1365–1372. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1365-1372.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raux H, Coulon P, Lafay F, Flamand A. Monoclonal antibodies which recognize the acidic configuration of the rabies glycoprotein at the surface of the virion can be neutralizing. Virology. 1995;210(2):400–408. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roche S, Gaudin Y. Characterization of the equilibrium between the native and fusion-inactive conformation of rabies virus glycoprotein indicates that the fusion complex is made of several trimers. Virology. 2002;297(1):128–135. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paroutis P, Touret N, Grinstein S. The pH of the secretory pathway: measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:207–215. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00005.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gaudin Y, Tuffereau C, Durrer P, Flamand A, Ruigrok RW. Biological function of the low-ph, fusion-inactive conformation of rabies virus glycoprotein G: G is transported in a fusion-inactive state-like conformation. J. Virol. 1995;69(9):5528–5534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5528-5534.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kampmann T, Mueller Ds, Mark AE, Young PR, Kobe B. The role of histidine residues in low-pH-mediated viral membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 2006;14(10):1481–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carneiro FA, Stauffer F, Lima CS, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Da Poian AT. Membrane fusion induced by vesicular stomatitis virus depends on histidine protonation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(16):13789–13794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lorizate M, Huarte N, Saez-Cirion A, Nieva JL. Interfacial pre-transmembrane domains in viral proteins promoting membrane fusion and fission. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778(7-8):1624–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suarez T, Gallaher WR, Agirre A, Goni FM, Nieva JL. Membrane interface-interacting sequences within the ectodomain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein: putative role during viral fusion. J. Virol. 2000;74(17):8038–8047. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8038-8047.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bellamy-Mcintyre AK, Lay CS, Baar S, et al. Functional links between the fusion peptide-proximal polar segment and membrane-proximal region of human immunodeficiency virus gp41 in distinct phases of membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(32):23104–23116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jeetendra E, Ghosh K, Odell D, Li J, Ghosh HP, Whitt MA. The membrane-proximal region of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G ectodomain is critical for fusion and virus infectivity. J. Virol. 2003;77(23):12807–12818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12807-12818.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shokralla S, Chernish R, Ghosh HP. Effects of double-site mutations of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G on membrane fusion activity. Virology. 1999;256(1):119–129. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jeetendra E, Robison CS, Albritton LM, Whitt MA. The membrane-proximal domain of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein functions as a membrane fusion potentiator and can induce hemifusion. J. Virol. 2002;76(23):12300–12311. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12300-12311.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kemble GW, Danieli T, White JM. Lipid-anchored influenza hemagglutinin promotes hemifusion, not complete fusion. Cell. 1994;76(2):383–391. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nussler F, Clague MJ, Herrmann A. Meta-stability of the hemifusion intermediate induced by glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored influenza hemagglutinin. Biophys. J. 1997;73(5):2280–2291. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Odell D, Wanas E, Yan J, Ghosh HP. Influence of membrane anchoring and cytoplasmic domains on the fusogenic activity of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. J. Virol. 1997;71(10):7996–8000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7996-8000.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cleverley DZ, Lenard J. The transmembrane domain in viral fusion: essential role for a conserved glycine residue in vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(7):3425–3430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cleverley DZ, Geller HM, Lenard J. Characterization of cholesterol-free insect cells infectible by baculoviruses: effects of cholesterol on vsv fusion and infectivity and on cytotoxicity induced by influenza M2 protein. Exp. Cell Res. 1997;233(2):288–296. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rose JK, Adams GA, Gallione CJ. The presence of cysteine in the cytoplasmic domain of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein is required for palmitate addition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:2050–2054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Whitt MA, Rose JK. Fatty acid acylation is not required for membrane fusion activity or glycoprotein assembly into VSV virions. Virology. 1991;185:875–878. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90563-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]