Abstract

Background

The relations of lipid concentrations to heart failure (HF) risk have not been comprehensively elucidated.

Methods and Results

In 6860 Framingham Heart Study participants (mean age 44 years; 54% women) free of baseline coronary heart disease, we related high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and non-HDL-C to HF incidence during long-term follow-up, adjusting for clinical covariates and myocardial infarction (MI) at baseline and updating these at follow-up examinations. We evaluated dyslipidemia-specific population burden of HF by calculating population attributable risks (PAR).

During follow-up (mean of 26 years), 680 participants (49% women) developed HF. Unadjusted HF incidence in the low (<160mg/dl) vs. high (≥190mg/dl) non-HDL-C groups was 7.9% and 13.8%, respectively, whereas incidence in the high (≥55 [men], ≥65 [women]mg/dl) vs. low (003C 40 [men], <50 [women]mg/dl) HDL-C groups was 6.1% and 12.8%, respectively. In multivariable models, baseline non-HDL-C and HDL-C, modeled as continuous measures, carried HF hazards (confidence interval-CI) of 1.19 (1.11–1.27) and 0.82 (0.75–0.90) respectively per standard deviation (SD) increment. In models updating lipid concentrations every 8 years, the corresponding hazards (CI) were 1.23 (1.16–1.31) and 0.77 (0.70–0.85). Participants with high baseline non-HDL-C and those with low HDL-C experienced a 29% and 40% higher HF risk respectively, compared to those in the desirable categories; the PARs for high non-HDL-C and low HDL-C were 7.5% and 15% respectively. Hazards associated with non-HDL-C and HDL-C remained statistically significant after additional adjustment for interim MI.

Conclusion

Dyslipidemia carries HF risk independent of its association with MI, suggesting that lipid modification may be a means for reducing HF risk.

Keywords: Heart failure, dyslipidemia, total cholesterol, HDL-C, non-HDL-C

Introduction

Heart Failure (HF) is a syndrome associated with high morbidity and mortality and enormous economic burden, rendering prevention a priority.1 Elucidating modifiable risk factors for HF will aid the identification and promulgation of prevention strategies. Dyslipidemia is a well-established risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD),2 and results from clinical trials of lipid-modifying therapy demonstrate that treatment with statins also decreases the incidence of HF.3 This finding suggests that dyslipidemia is a risk factor for HF, although the association may be mediated by the occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI).

Although previous studies assessed the associations between individual lipid measures and HF,4,5 the role of lipids in the incidence of HF in people without pre-existing CHD has not been systematically investigated in a community-based setting in a prospective fashion, with appropriate adjustment for clinical factors (including interim occurrence of MI) that influence HF risk. Elevated low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) have been shown to be associated with reduced systolic and diastolic LV function.6,7 Also, a previous investigation from the Framingham Heart Study detected a direct association between the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL-C and HF risk,5 suggesting that either elevated total cholesterol, or a lowered HDL-C may influence HF risk. We therefore hypothesized that increasing levels of non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) and decreasing levels of HDL-C are associated with increased risk for HF. We further theorized that the associations between lipid concentrations and HF will persist even after adjustment for occurrence of interim MI.

Methods

Study Sample and Design

The design and characteristics of the Framingham Heart Study original cohort 8,9 and offspring cohort 10 have been detailed elsewhere. Briefly, the original cohort included 5209 participants who were enrolled in 1948 and have been evaluated every two years. The offspring cohort, consisting of 5124 individuals who are children (or spouses of children) of the original cohort, was enrolled in 1971 and has been examined approximately every four years.

Attendees of examinations 11 (1968–1971) and 12 (1971–1974) of the original cohort and examination 1 (1971–1974) of the offspring cohort who had lipids measured formed the baseline for this analysis (n = 7598). We excluded 510 participants because of prevalent HF, MI, angina pectoris, coronary insufficiency, valve disease, or use of lipid therapy at the baseline examination, and 228 participants because of missing covariate information. Valve disease was defined as a systolic murmur grade three out of six or louder or any diastolic murmur, as auscultated by a physician during the clinical examination. A total of 6860 participants (mean age = 44; 54% women) were eligible for this investigation. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Center.

Measurement of Circulating Lipids

Plasma samples for lipid measurement were collected in 0.1% EDTA and lipid concentrations were measured on freshly drawn plasma before freezing. Total cholesterol was measured by the Abell and Kendall method up to original cohort examination 20 (1986–1990) and subsequently by standard enzymatic methods.11,12 HDL-C was measured after heparin-manganese chloride precipitation13 (up to Offspring cohort examination cycle 4 – years 1987–1991) and subsequently by dextran sulfate-manganese precipitation. HDL-C was subtracted from total cholesterol to obtain non-HDL-C. The utility of non-HDL-C as a predictor of the lipoprotein related risk for atherosclerotic disease has been established previously.14

Determination of HF Events

An ongoing review of clinic charts, hospitalization and physician records, and mailed health history updates from participants is performed at the Framingham heart Study, according to pre-specified protocols. All suspected cardiovascular events were reviewed by a committee of three physicians according to established criteria.15 For this investigation, the outcome of interest was the first occurrence of HF as adjudicated by an endpoints committee. The criteria for HF have been published previously16 and are detailed in Supplementary Table A.

Definitions of Covariates

Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. At each examination, blood pressure was measured twice by a physician on the left arm in the seated position using a mercury column sphygmomanometer and we used the average of these values. Current smoking was defined as smoking (on average) one or more cigarettes per day in the year preceding an examination. Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose of 126 mg/dl or greater, a non-fasting glucose of 200 mg/dl or greater, or current use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic therapy. Treatment status for hypertension was defined as receiving blood pressure lowering medications for treatment of hypertension. Interim MI was defined as MI occurring between the examination at which lipids were measured and the date of diagnosis of HF.

Statistical Analysis

We related baseline HDL-C and non-HDL-C, both as continuous and categorical variables (see below), to HF incidence. We used Cox Proportional Hazards models (after confirming that the assumption of proportionality was met) to relate lipid concentrations (continuous and categorical) to the incidence of HF in stepwise fashion. We constructed two models: a model adjusting for traditional HF risk factors (age, sex, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, body mass index, smoking status and diabetes) and a model adjusting for traditional covariates plus interim MI as a time-dependant covariate (participants with MI at baseline were excluded from eligibility). Further, we examined lipid categories published by the National Cholesterol Education Program17 and sex-specific distributions of lipid concentrations in the Lipid Research Clinics18 and grouped participants based on their baseline lipid concentrations as follows:

HDL-C (mg/dl): For men; <40, 40–54, 55 or greater (referent group). For women; <50, 50–64, 65 or greater (referent group)

Non-HDL-C (mg/dl): <160 (referent group), 160–189, 190 or greater.

We first ascertained HF event proportions and age- and sex-adjusted HF event rates in each lipid category. We then incorporated lipid categories as predictor variables in the aforementioned models and related the categories to HF incidence.

Since lipid concentrations and values of other covariates change over time and these changes may influence the relations of lipids to HF incidence, we repeated Cox proportional hazards regression updating lipid concentrations and the complete covariate profile approximately every 8 years after the initial baseline (every 4th examination for the original cohort, and approximately every other examination for the offspring cohort) for each participant. For analyses of lipid categories, participants were re-grouped based on the lipid levels at the beginning of the relevant 8-year period. If a participant experienced a MI, angina pectoris, coronary insufficiency or HF event before a given 8-year interval, the participant was considered as having a prevalent event and was excluded for that and all subsequent 8-year intervals. If a participant had valve disease or was receiving lipid lowering therapy or had missing lipid information at the beginning of a given 8-year period, we excluded that person for that analysis interval. We also performed tests for sex interaction to determine if there was need for sex-specific analyses.

Non-optimal lipid concentrations are widely prevalent in the population.19 Therefore, we sought to evaluate the population burden of HF secondary to dyslipidemia by calculating category-specific population attributable risk (PAR), as a function of the proportion of cases (Pd) of HF occurring in each category of HDL-C and non-HDL-C and the relative risk (RR – the hazards ratio from the model adjusting for clinical covariates). The formula we used (expressing PAR as a percentage) is:

Hazards ratios are expressed per standard deviation increment in a lipid value (for analyses using lipids as continuous variables), or comparing the non-optimal lipid concentrations to the referent category. A p-value threshold of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.0 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The baseline characteristics of the study sample are detailed in Table 1. Overall, 58% of participants were alive at the end of the follow-up period and were censored at that point. Causes of death in the others were: CHD (6%), other cardiovascular causes (6%), cancer (12%), other non-cardiovascular or non-cancer deaths (14%) and unknown (4%). Over a mean follow up of 26 years (maximum 37 years), 680 participants (10%; 335 women; 345 men) developed a first HF event. For those participants who developed HF, mean time to event was 21 years (median = 22 years, range = 0.15 – 35 years). Of participants who developed HF, 41% had a preceding MI. Among participants who developed HF, the proportion with interim MI rose from 33% to 48% across categories of increasing non-HDL-C. The proportion of HF cases with interim MI decreased from 48% to 28% across categories of increasing HDL-C. Tests for sex interactions were negative; therefore only sex-pooled results are presented here. HF event rates increased across categories of non-HDL-C and decreased across categories of HDL-C both in analyses modeling only baseline lipid concentrations and those incorporating periodically updated lipid concentrations. Table 2 presents analyses modeling baseline lipid concentrations and periodically updated lipid concentrations as continuous variables. Table 3 (baseline) and Table 4 (periodically updated) present analyses modeling lipid categories. Participants in the lower categories of HDL-C and higher categories of non-HDL-C received beta-blockers, diuretics, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors – drugs that may favorably alter the risk of HF - in higher proportions than participants in the referent groups (Supplementary Table B).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| Clinical Covariate, mean (SD), or % | Total Participants (N = 6860) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 44 (15) |

| Women | 54 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.3 (4.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 127 (20) |

| Smoking | 41 |

| Diabetes | 3.7 |

| Hypertension | 29 |

| Hypertension Treatment | 6.3 |

| Interim MI | 4.1 |

| Lipid Measure, mean (SD) | |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dl | 209 (43) |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 52 (16) |

| Non-HDL-C, mg/dl | 156 (45) |

SD = standard deviation; Interim MI = Myocardial infarction that occurred between baseline examination and diagnosis of heart failure; mg/dl = milligrams per deciliter; HDL-C = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; Non-HDL-C = Total cholesterol minus HDL-C.

Table 2.

Relations of lipid concentrations to HF incidence

| Multivariable adjusted | Multivariable + Interim MI adjusted |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| A. Single baseline measurements | ||||||

| HDL-C | 0.82 | 0.75 – 0.90 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.81 – 0.98 | 0.02 |

| Non-HDL-C | 1.19 | 1.11 – 1.27 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.01 – 1.16 | 0.02 |

| B. Lipid values updated every 8 years | ||||||

| HDL-C | 0.77 | 0.70 – 0.85 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.76 – 0.92 | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 1.23 | 1.16 – 1.31 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 1.03 – 1.20 | 0.005 |

Analyses of single baseline measurements were based on mean 26 years (maximum 37 years) of follow-up.

HR = hazards ratio per standard deviation change in lipid value; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals; Interim MI = MI occurring between baseline examination and diagnosis of heart failure.

Multivariable models adjusted for the following covariates: age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, diabetes and smoking.

Table 3.

Long-term follow-up relating baseline lipid categories to HF incidence

| HDL-C | Men <40; Women <50 |

Men 40–54 Women 50– 64 |

Men ≥55; Women ≥65 |

p-value (trend) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events/No. at risk (%) | 342/2665 (12.8%) |

245/2666 (9.2%) |

93/1529 (6.1%) |

N/A | |

| Hazards ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariable adjusted |

Referent | 0.77 (0.65 – 0.91) |

0.60 (0.48 – 0.74) |

<0.001 |

| Multivariable + MI adjusted |

Referent | 0.88 (0.74 – 1.05) |

0.75 (0.60 – 0.93) |

0.010 | |

| Non-HDL-C | <160 | 160 – 189 | ≥190 |

p-value (trend) |

|

| No. of events/No. at risk (%) | 261/3302 (7.9%) |

176/1795 (9.8%) |

243/1763 (13.8%) |

N/A | |

| Hazards ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariable adjusted |

Referent | 1.04 (0.85 – 1.26) |

1.29 (1.08 – 1.55) |

0.005 |

| Multivariable + MI adjusted |

Referent | 0.93 (0.76 – 1.13) |

1.13 (0.94 – 1.35) |

0.186 | |

Analyses were based on mean 26 years (maximum 37 years) of follow-up. Multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, diabetes and smoking.

Multivariable + MI model adjusted for interim MI as a time dependant covariate in addition to clinical covariates.

Table 4.

8-Year Hazards of HF (lipid values updated at each examination) according to lipid categories

| HDL-C | Men <40; Women <50 |

Men 40–54 Women 50–64 |

Men ≥55; Women ≥65 |

p-value (trend) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events/No. of person- years (PY) at risk (%) |

342/572.11 (0.60 events/100- PY) |

245/731.56 (0.33 events/100-PY) |

93/455.61 (0.20 events/100-PY) |

N/A | |

| Hazards ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariable adjusted |

Referent | 0.79 (0.67 – 0.94) |

0.57 (0.45 – 0.72) |

<0.001 |

| Multivariable + MI adjusted |

Referent | 0.86 (0.73 – 1.02) |

0.71 (0.56 – 0.90) |

<0.001 | |

| Non-HDL-C | <160 | 160 – 189 | ≥190 |

p-value (trend) |

|

| No. of events/No. of person- years (PY) at risk (%) |

261/1052.33 (0.25 events/100- PY) |

176/366.69 (0.48 events/100-PY) |

243/340.24 (0.71 events/100-PY) |

N/A | |

| Hazards ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariable adjusted |

Referent | 1.03 (0.85 – 1.24) |

1.53 (1.28 – 1.83) |

<0.001 |

| Multivariable + MI adjusted |

Referent | 0.85 (0.70 – 1.04) |

1.17 (0.98 – 1.40) |

<0.001 | |

Multivariable model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, diabetes and smoking.

Multivariable + MI model adjusted for interim MI as a time dependant covariate in addition to clinical covariates.

Relations of HDL-C to HF incidence

In analyses modeling HDL-C as a continuous variable, we observed an 18% lower risk for HF with each SD increase in baseline HDL-C levels (Table 2.A). When HDL-C concentrations were updated at each examination, the decrement in HF risk was 23% for each SD increase of HDL-C (Table 2.B). Even after adjustment for interim MI, both baseline and periodically updated HDL-C concentrations were significantly related to HF incidence (11% and 16% lower HF risk per SD increase in baseline and updated HDL-C levels, respectively; Table 2).

In models incorporating HDL-C categories (Table 3), participants in intermediate and high baseline HDL-C categories experienced a 23% and 40% lower risk of HF respectively, compared to the low HDL-C group. When HDL-C values were updated every 8 years, participants in the intermediate and high HDL-C categories experienced a 21% and 43% lower HF risk respectively, compared to the low HDL-C category (Table 4). In analyses adjusted for interim MI, there was a modest attenuation of the hazards ratios, but the inverse relation between HDL-C levels and HF risk persisted (Tables 3 and 4). Kaplan-Meier curves for survival free of HF in each HDL-C category are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of unadjusted survival free of HF in each HDL-C category.

Relations of Non-HDL-C to HF incidence

Participants with elevated baseline (Table 2.A) and periodically updated (Table 2.B) non-HDL-C concentrations were at a 19% and 23% higher risk for HF, respectively. These relations remained robust even after adjustment for interim MI; we observed an 11% increment in HF risk for each SD increment in non-HDL-C (Table 2.B). When modeled as a categorical variable, participants in the highest category of non-HDL-C were at increased risk compared to participants in the lowest non-HDL-C group. Adjustment for MI modestly attenuated the effect size.

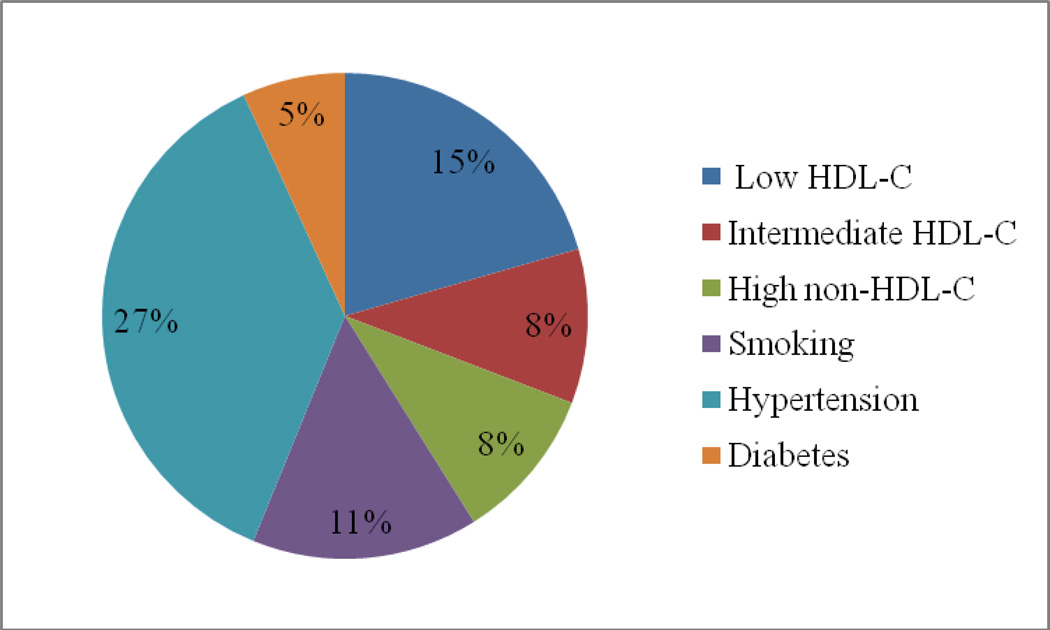

Population Attributable Risk (PAR)

The hazards associated with lipids and other HF risk factors, and the corresponding PARs are presented in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table C. The PAR of HF associated with elevated non-HDL-C (≥ 190 mg/dl) was 7.5%. The PAR for low HDL-C (< 40 mg/dl [men] and < 50 mg/dl [women]) was 15%. Dyslipidemia (either elevated non-HDL-C [≥ 190 mg/dl] or low HDL-C [(< 40 mg/dl in men and < 50 mg/dl in women]) had a PAR of 22.5%.

Figure 2. Population attributable risks of major HF risk factors.

Population attributable risks were calculated from a model that adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), smoking (yes/no), and HDL-C (men: <40 mg/dl, 40–54 mg/dl, 55 mg/dl or greater; women: <50 mg/dl, 50–64 mg/dl, 65 mg/dl or greater) and non-HDL-C (<160 mg/dl, 160–189 mg/dl, 190 mg/dl or greater) categories.

Discussion

Principal Findings

In our large community-based sample of adults free of prevalent CHD, elevated non-HDL-C and decreased HDL-C were associated with increased risk of HF. The relations of lipid concentrations to HF incidence were continuous and graded in models adjusting for established HF risk factors, and persisted after adjustment for interim MI. A novel finding of our study is the inverse association between HDL-C concentrations and HF risk. HDL-C was especially robust as a predictor, whether modeled as a continuous or categorical variable and when assessed as a single baseline measurement or a periodically updated measure, and 15% of all cases of HF were attributable to low HDL-C concentrations (< 40 mg/dl in men and < 50 mg/dl in women).

Dyslipidemia is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and predisposition to MI is one mechanism by which lipids promote the occurrence of HF. In our investigation, after excluding baseline CHD and accounting for interim MI, we observed an enduring relation between lipid concentrations and HF incidence, suggesting an influence of lipids on HF risk that is not mediated by MI. Although results from observational studies cannot establish causation, the strength, direction, and continuous nature of the association and the temporal sequence are consistent with a causal relation. However, it is possible that the relations of lipid level abnormalities to HF risk that are unexplained by clinically diagnosed MI are driven by unrecognized infarction. Indeed, it has been estimated that a quarter to a third of all MIs are clinically undetected.20,21 Thus the residual HF risk we observe after adjustment for clinical MI may be due to undetected events.

Lipids and HF: Comparison with the Published Literature

Previous observational studies have addressed associations of lipid measures with incidence of HF. Kannel et al reported that an elevated total/HDL ratio is associated with increased HF risk.5 Another report from the Framingham Heart Study noted an association, albeit of modest magnitude, between total cholesterol and HF risk.22 Elevated triglycerides have been implicated in HF incidence in the elderly.4 One case-control study reported independent associations between decreased HDL-C and elevated triglycerides and dilated cardiomyopathy.23 Ingelsson et al identified decreased HDL-C and an elevated apolipoprotein B/A-1 ratio (the ratio of the main lipoproteins in LDL-C and HDL-C respectively) as independent predictors of HF risk in a prospective community-based study.24 Investigators from the Physician Health Study identified egg consumption (a rich source of cholesterol) as a risk factor for HF.25 Similarly, increased intake of saturated fat was also implicated as a HF risk factor in a report from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study.26 Another prospective study from Uppsala identified metabolic syndrome (typically associated with elevated triglycerides and low HDL-C) as a HF risk factor.27 Prior investigations, however, were limited by lack of systematic exclusion of baseline CHD and did not consistently adjust for a panel of clinical covariates including interim MI. Furthermore, previous studies did not assess the full range of lipid level alterations.

Lipids and HF: Possible Mechanisms Underlying the Observed Association

Although some have argued that dyslipidemia influences risk of MI but not of HF,28 a hypothesis that is supported by our study is that lipid abnormalities exert effects on the myocardium independent of MI. Several lines of evidence implicate lipid derangements in the development of abnormal cardiac structure and function. Observations in humans demonstrate that elevated total cholesterol is related to increased blood pressure,29 increased arterial stiffness30 and decreased vascular compliance,29 and an increased left ventricular mass and wall thickness.29,31 Experimental evidence from animals fed a high cholesterol diet shows that diet-induced hypercholesterolemia leads to decreased systolic and diastolic function,32 increased left ventricular end-diastolic volume and pressure33 and decreased myocardial perfusion responsiveness to stress.34 Decreased HDL-C concentrations are associated with increased left ventricular mass,35 decreased diastolic function36 and a lower ejection fraction in people with both normal and stenosed coronary arteries.37 In addition, retrospective analyses from some clinical trials demonstrated a decrease in the incidence of HF in people with dyslipidemia treated with lipid modifying therapy.3 Clinical trials have also demonstrated improved outcomes after treatment with statins in individuals with HF who have dyslipidemia but no discernable CHD.38

The inverse association between HDL-C concentrations and HF risk may be mediated by the cardiovascular protective effects of the HDL particle. Apart from amelioration of atherosclerosis by promoting cholesterol efflux from macrophages (and thereby decreasing MI risk and risk of post-MI HF), HDL and its constituent proteins have pleiotropic biological effects.39 Inflammation has been previously implicated in HF development,40 and HDL has anti-inflammatory properties41 and can therefore exert a protective effect. HDL also inhibits expression of cell surface adhesion molecules that promote monocyte infiltration into the endothelium,42 further reducing the inflammatory processes that are precursors to clinical HF. Elevated HDL concentrations improve endothelial function,43 and reduce LDL oxidation,44 thereby protecting against vascular remodeling and myocardial ischemia. HDL also improves endothelial repair mediated by progenitor cells,45 thus decreasing the risk of cardiac and vascular remodeling. These mechanisms may explain the “protective” effect of HDL-C.

Of note are two recent clinical trials that evaluated the efficacy of rosuvastatin in reducing the risk of cardiovascular death, non-fatal cardiovascular events and HF hospitalization in patients with established class II, III and IV HF. Neither the “Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure” (CORONA) trial,46 nor the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Insufficienza cardiac (GISSI-HF) trial,47 found a survival benefit in HF patients from treatment with this agent. HF is an end-stage event, and is a manifestation of a lifetime of risk factor exposure, myocardial injury and fibrosis. Thus is it possible that although abnormal lipid concentrations influence the risk for new-onset HF, modifying lipid levels in patients with established HF may not improve survival because the myocardial damage at that stage of disease may not be remediable to lipid lowering therapy.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is the large sample size and number of events, judicious exclusions at baseline to minimize confounding by prevalent CHD, careful surveillance for and standardized definition of HF events, comprehensive analyses of major lipid sub-fractions without and with adjustment for interim MI on follow-up, and the use of models to assess both intermediate and long-term effects of altered lipid concentrations.

Nevertheless, several limitations of our study should be recognized. Although we were careful to exclude prevalent CHD, the results may be confounded by undetected disease present at baseline or unrecognized events occurring during follow up. Triglycerides measurement were not consistently available at all examination cycles and in all participants so we were unable to evaluate the relations of triglycerides (or calculate low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations) to HF risk. Aggressive treatment of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia and concurrent lifestyle changes after MI may modify the magnitude of risk associated with these factors, a confounding effect that is not fully accounted for by our time-dependent analyses. It is possible that differences across lipid categories in the use of diuretics, beta blockers, and ACE inhibitors – drugs that may prevent HF -- influenced our results. Since more participants in the high risk lipid groups received these agents compared to the referent groups (Supplementary Table B), this disproportion in potentially beneficial treatment across groups may have biased our results toward the null. We lacked information on ejection fraction, and were thus unable to ascertain if lipid concentrations were related to HF with reduced ejection fraction, HF with normal ejection fraction, or both. Last, our study sample was comprised of individuals of European descent, and so our results may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of lipid concentrations derived from prospective observation of a healthy, free-living sample, we demonstrate that elevated levels of non-HDL-C and decreased levels of HDL-C are associated with increased risk of HF. It is noteworthy that 15% of heart failure cases were attributable to low HDL-C concentrations. The HF risk associated with dyslipidemia appears to be partly independent of the influence of lipids on risk of MI. These findings lend mechanistic support to previous observations of benefit from lipid therapy in reducing HF incidence. Given the high prevalence of dyslipidemia in the community19, our report highlights the possibility of reducing HF burden by targeting abnormal lipid concentrations for treatment.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding Sources: The Framingham Heart Study is supported by NIH contract NO1-HC-25195

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None

Reference List

- 1.Schocken DD, Benjamin EJ, Fonarow GC, Krumholz HM, Levy D, Mensah GA, Narula J, Shor ES, Young JB, Hong Y. Prevention of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Epidemiology and Prevention, Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and High Blood Pressure Research ; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2008;117:2544–2565. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamler J, Wentworth D, Neaton JD. Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) JAMA. 1986;256:2823–2828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin JH, Krum H. Statins and clinical outcomes in heart failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:119–127. doi: 10.1042/CS20070031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eriksson H, Svardsudd K, Larsson B, Ohlson LO, Tibblin G, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L. Risk factors for heart failure in the general population: the study of men born in 1913. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:647–656. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannel WB, Ho K, Thom T. Changing epidemiological features of cardiac failure. Br Heart J. 1994;72:S3–S9. doi: 10.1136/hrt.72.2_suppl.s3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmiero P, Maiello M, Passantino A, Antoncecchi E, Deveredicis C, DeFinis A, Ostuni V, Romano E, Mengoli P, Caira D. Correlation between diastolic impairment and lipid metabolism in mild-to-moderate hypertensive postmenopausal women. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:615–620. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)02934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rietzschel ER, Langlois M, De Buyzere ML, Segers P, De Bacquer D, Bekaert S, Cooman L, Van Oostveldt P, Verdonck P, De Backer GG, Gillebert TC. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is associated with decreases in cardiac function independent of vascular alterations. Hypertension. 2008;52:535–541. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE., Jr Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41:279–281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.41.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell LP. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Framingham Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;107:539–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb13299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson PW, Hoeg JM, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Belanger AM, Poehlmann H, O'Leary D, Wolf PA. Cumulative effects of high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, and cigarette smoking on carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:516–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708213370802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNamara JR, Schaefer EJ. Automated enzymatic standardized lipid analyses for plasma and lipoprotein fractions. Clin Chim Acta. 1987;166:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(87)90188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albers JJ, Warnick GR, Wiebe D, King P, Steiner P, Smith L, Breckenridge C, Chow A, Kuba K, Weidman S, Arnett H, Wood P, Shlagenhaft A. Multi-laboratory comparison of three heparin-Mn2+ precipitation procedures for estimating cholesterol in high-density lipoprotein. Clin Chem. 1978;24:853–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost PH, Havel RJ. Rationale for use of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol rather than low-density lipoprotein cholesterol as a tool for lipoprotein cholesterol screening and assessment of risk and therapy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:26B–31B. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Garrison RJ, editors. Some Risk Factors Related to the Annual Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease and Death in Pooled Repeated Biennial Measurements. Section 34. The Framingham Heart Study: 30 Year Follow-Up. NIH publication 87-2703. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Lipid Research Clinics Population Studies Data Book: Volume 1. The Prevalence Study; Section II: "Plasma lipids and lipoproteins by age, race, sex and hormone usage 200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern SM, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wilson M, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kannel WB, Abbott RD. Incidence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction. An update on the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1144–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198411013111802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheifer SE, Manolio TA, Gersh BJ. Unrecognized myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:801–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronmal RA, Cain KC, Ye Z, Omenn GS. Total serum cholesterol levels and mortality risk as a function of age. A report based on the Framingham data. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1065–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skwarek M, Bilinska ZT, Mazurkiewicz L, Grzybowski J, Kruk M, Kurjata P, Piotrowski W, Ruzyllo W. Significance of dyslipidaemia in patients with heart failure of unexplained aetiology. Kardiol Pol. 2008;66:515–22, discussion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingelsson E, Arnlov J, Sundstrom J, Zethelius B, Vessby B, Lind L. Novel metabolic risk factors for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2054–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djousse L, Gaziano JM. Egg consumption and risk of heart failure in the Physicians' Health Study. Circulation. 2008;117:512–516. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamagishi K, Nettleton JA, Folsom AR. Plasma fatty acid composition and incident heart failure in middle-aged adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J. 2008;156:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingelsson E, Arnlov J, Lind L, Sundstrom J. Metabolic syndrome and risk for heart failure in middle-aged men. Heart. 2006;92:1409–1413. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.089011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhingra R, Sesso HD, Kenchaiah S, Gaziano JM. Differential effects of lipids on the risk of heart failure and coronary heart disease: the Physicians' Health Study. Am Heart J. 2008;155:869–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Celentano A, Crivaro M, Roman MJ, Pietropaolo I, Greco R, Pauciullo P, Lirato C, Devereux RB, de Simone G. Left ventricular geometry and arterial function in hypercholesterolemia. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2001;11:312–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiffrin EL. Vascular stiffening and arterial compliance. Implications for systolic blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:39S–48S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jullien V, Gosse P, Ansoborlo P, Lemetayer P, Clementy J. Relationship between left ventricular mass and serum cholesterol level in the untreated hypertensive. J Hypertens. 1998;16:1043–1047. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Y, Walker KE, Hanley F, Narula J, Houser SR, Tulenko TN. Cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction after a cholesterol-rich diet. Circulation. 2004;109:97–102. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109213.10461.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maczewski M, Maczewska J. Hypercholesterolemia exacerbates ventricular remodeling in the rat model of myocardial infarction. J Card Fail. 2006;12:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez-Porcel M, Lerman A, Best PJ, Krier JD, Napoli C, Lerman LO. Hypercholesterolemia impairs myocardial perfusion and permeability: role of oxidative stress and endogenous scavenging activity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schillaci G, Vaudo G, Reboldi G, Verdecchia P, Lupattelli G, Pasqualini L, Porcellati C, Mannarino E. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2001;19:2265–2270. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horio T, Miyazato J, Kamide K, Takiuchi S, Kawano Y. Influence of low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol on left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic function in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:938–944. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang TD, Lee CM, Wu CC, Lee TM, Chen WJ, Chen MF, Liau CS, Sung FC, Lee YT. The effects of dyslipidemia on left ventricular systolic function in patients with stable angina pectoris. Atherosclerosis. 1999;146:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojnicz R, Wilczek K, Nowalany-Kozielska E, Szygula-Jurkiewicz B, Nowak J, Polonski L, Dyrbus K, Badzinski A, Mercik G, Zembala M, Wodniecki J, Rozek MM. Usefulness of atorvastatin in patients with heart failure due to inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy and elevated cholesterol levels. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah PK, Kaul S, Nilsson J, Cercek B. Exploiting the vascular protective effects of high-density lipoprotein and its apolipoproteins: an idea whose time for testing is coming, part I. Circulation. 2001;104:2376–2383. doi: 10.1161/hc4401.098467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, Dinarello CA, Harris T, Benjamin EJ, Sawyer DB, Levy D, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:1486–1491. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057810.48709.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cockerill GW, Huehns TY, Weerasinghe A, Stocker C, Lerch PG, Miller NE, Haskard DO. Elevation of plasma high-density lipoprotein concentration reduces interleukin-1-induced expression of E-selectin in an in vivo model of acute inflammation. Circulation. 2001;103:108–112. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barter PJ, Baker PW, Rye KA. Effect of high-density lipoproteins on the expression of adhesion molecules in endothelial cells. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:285–288. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spieker LE, Sudano I, Hurlimann D, Lerch PG, Lang MG, Binggeli C, Corti R, Ruschitzka F, Luscher TF, Noll G. High-density lipoprotein restores endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic men. Circulation. 2002;105:1399–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013424.28206.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackness MI, Arrol S, Abbott C, Durrington PN. Protection of low-density lipoprotein against oxidative modification by high-density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase. Atherosclerosis. 1993;104:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(93)90183-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tso C, Martinic G, Fan WH, Rogers C, Rye KA, Barter PJ. High-density lipoproteins enhance progenitor-mediated endothelium repair in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1144–1149. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216600.37436.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kjekshus J, Apetrei E, Barrios V, Bohm M, Cleland JG, Cornel JH, Dunselman P, Fonseca C, Goudev A, Grande P, Gullestad L, Hjalmarson A, Hradec J, Janosi A, Kamensky G, Komajda M, Korewicki J, Kuusi T, Mach F, Mareev V, McMurray JJ, Ranjith N, Schaufelberger M, Vanhaecke J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Waagstein F, Wedel H, Wikstrand J. Rosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2248–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gissi-HF I, Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, Marchioli R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Latini R, Lucci D, Nicolosi GL, Porcu M, Tognoni G. Effect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]