CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old woman presented with worsening right hearing loss, aural fullness, and bilateral tinnitus. Nine years before presentation, the patient was involved in 2 motor vehicle accidents and subsequently complained of chronic nonpostural headaches. Audiograms demonstrated an initial right mild low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) progressing to downsloping mild-to-profound SNHL for 4 years (Fig. 1). Acoustic reflexes were absent. No abnormalities were noted on physical examination or laboratory testing, including basic chemistries, complete blood cell count, thyroid-stimulating hormone, rapid plasma reagin, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, Lyme titers, antinuclear antibodies, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

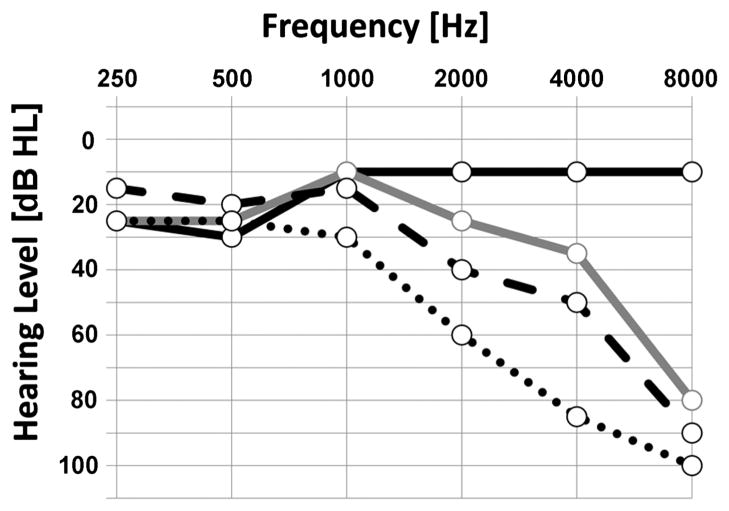

FIG. 1.

Serial audiograms demonstrate progressive right sensorineural hearing loss for 4 years’ time. Black solid line indicates audiogram from 2007; gray solid line, 2008; dashed line, 2009; dotted line, 2010. Right word recognition scores were 100% until 2010, when it dropped to 92%. Acoustic reflexes were absent in the right ear in all audiograms obtained.

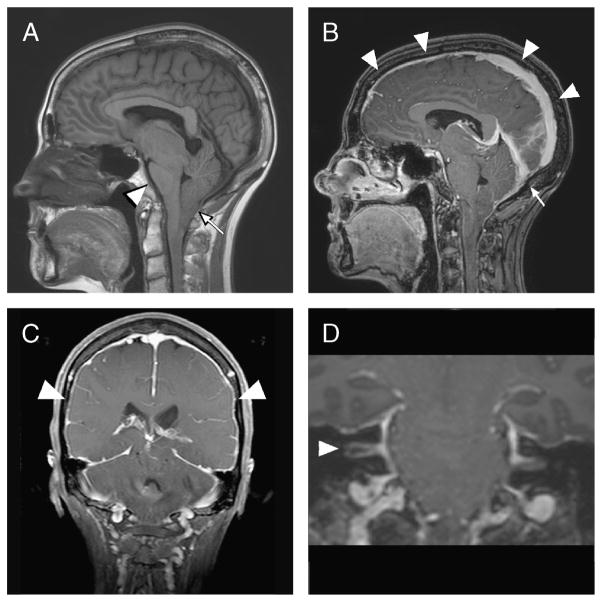

Magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a caudally displaced brain, with descent of cerebellar tonsils, crowding of the foramen magnum and near complete effacement of the interpeduncular cisterns (Fig. 2A). There was diffuse dural enhancement and venous engorgement present on the gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image, notably extending into the right internal auditory canal (Fig. 2, B and C). There was no evidence of a mass lesion in the internal auditory canals or cerebellopontine angles (Fig. 2, C and D). Similar findings were noted on a previous MRI 1.5 years after her second motor vehicle crash.

FIG. 2.

A, Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image from 2010 demonstrates caudal displacement of intracranial contents, including descent of the cerebellar tonsils with crowding of the foramen magnum (arrow) and flattening of the ventral pons against the clivus (arrowhead). B, Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image with gadolinium demonstrating prominent sagittal sinus (arrowheads) and transverse sinus (arrow). C, Coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image with contrast demonstrating diffuse dural enhancement (arrowheads). D, Coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image with contrast showing prominent enhancement resulting from venous engorgement of the porous acousticus of the internal auditory canals, with greater enhancement of the right internal auditory canal (arrowhead) than the left. No mass lesions are present within the internal auditory canals or cerebellopontine angles.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) occurs in 1 of 50,000 individuals per year with peak incidence in the fourth decade of life (1). Spontaneous intracranial hypotension results from structural weakness of the spinal meninges of radicular nerve roots that predisposes to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks (1,2). Connective tissue disorders, minor trauma, or vigorous exercise may lead to the development of this disorder, but for the majority of patients, the cause is unknown (1). Orthostatic headache that worsens with sitting up is typical; however, nonpostural chronic headache has been described (1). Headache results from CSF hypovolemia and meningeal irritation (1,3). Cranial nerve palsies are attributed to traction on intracranial structures due to caudal displacement of the brain. Hearing loss, vertigo, and tinnitus may also result from transmission of abnormal CSF pressure to the perilymph of the cochlea (3).

In a study of 30 consecutive patients with SIH, neurotologic symptoms included dizziness (30%), tinnitus (20%), aural fullness (20%), and hearing loss (3%) (4). Low-frequency unilateral or bilateral is typically described (2); however, high-frequency SNHL has been described (3). Progressive decline to profound SNHL has not been noted previously. Symptoms are often exacerbated by sitting or standing and relieved by lying flat. Hearing loss may fluctuate depending on hydration status.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain with gadolinium best establishes the diagnosis of SIH. Typical findings pachymeningeal enhancement, venous engorgement, pituitary hyperemia, brain descent, and subdural collections (3). Enhancement of the dura in SIH is diffuse, symmetric, and not nodular. In SIH cases in which dural enhancement is the only imaging finding present, the diagnosis can be difficult to differentiate from infectious, granulomatous, or idiopathic pachymeningitis (3). Descent of the brain is a more specific finding, manifested by caudal displacement of the floor of the third ventricle and cerebellar tonsils, flattening of the pons against the clivus, and effacement of the basilar cisterns (2). Cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure less than 6 cm H2O supports the diagnosis; however, some patients with SIH have normal opening pressures (1). Cerebrospinal fluid myelography can identify and localize CSF leaks, although small or slow leaks may not be demonstrated. Radionuclide cisternography is reserved for cases when CSF opening pressure and myelography are inconclusive (1,3).

Many cases are thought to spontaneously resolve, although this has not been proven (1). Medical management with bed rest, caffeine intake, and oral hydration may be sufficient to reduce symptoms. Epidural blood patch or percutaneous placement of fibrin sealant can be used to treat patients nonresponsive to conservative management. Surgical repair of the dura is rarely required (1,2). Recurrent CSF leak occurs in 10% of patients, and may be heralded by return of headache. After resolution of CSF leak, MRI abnormalities improve within days to weeks (1). Hearing thresholds may also decrease after resolution of the underlying pathologic disease (2,3,5).

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. JAMA. 2006;295:2286–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.19.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RS, Tami TA, Pensak M. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension mimicking Ménière’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:655–6. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blank SC, Shakir RA, Bindoff LA, et al. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(97)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung SJ, Kim JS, Lee MC. Syndrome of cerebral spinal fluid hypovolemia: clinical and imaging features and outcome. Neurology. 2000;55:1321–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.9.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taki M, Nin F, Hasegawa T, et al. Case report: two cases of hearing impairment due to intracranial hypotension. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:345–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]