Abstract

Context

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), characterized by recurrent arousals from sleep and intermittent hypoxemia, is common among older adults. Cross-sectional studies have linked SDB to poor cognition; however, it remains unclear whether sleep disordered breathing precedes cognitive impairment in older adults.

Objectives

To determine the prospective relationship between sleep disordered breathing and cognitive impairment and to investigate potential mechanisms of this association.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective sleep and cognition study of 298 women without dementia (mean [SD] age: 82.3 [3.2] years) who had overnight polysomnography (PSG) measured between January 2002 and April 2004 in a substudy of the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Sleep disordered breathing was defined as an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or more events per hour of sleep. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the independent association of sleep disordered breathing with risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia and adjustments were made for age, race, body mass index, education, smoking status, presence of diabetes, presence of hypertension, medication use (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, or non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics), and baseline cognitive scores. Measures of hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, and sleep duration were investigated as underlying mechanisms for this relationship.

Main Outcome Measures

Adjudicated cognitive status (normal, dementia, or mild cognitive impairment [MCI]) based on data collected between November 2006 and September 2008

Results

Compared with the 193 women without sleep disordered breathing, the 105 women (35.2%) with SDB were more likely to develop MCI/dementia (n=60 (31.1%) vs n=47 (44.8%)) even after multivariate adjustment (adjusted OR=1.85, 95% CI 1.11-3.08). Elevated oxygen desaturation index (≥15 events/hour) and high percentage (>7%) of sleep time in apnea or hypopnea, both measures of disordered breathing, were associated with risk of developing MCI/dementia (adjusted OR=1.71, 95% CI 1.04 − 2.83 and adjusted OR=2.04, 95% CI 1.10 − 3.78, respectively). Measures of sleep fragmentation (arousal index and wake after sleep onset) or sleep duration (total sleep time) were not associated with risk of cognitive impairment.

Conclusions

Among older women, those with sleep disordered breathing, compared with those without SDB, were associated with an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), a disorder characterized by recurrent arousals from sleep and intermittent hypoxemia, is common among older adults and affects up to 60% of elderly populations.1 A number of adverse health outcomes including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes have been associated with sleep disordered breathing.2-5 Cognitive impairment has also been linked to sleep disordered breathing, but the majority of studies have been cross-sectional or have relied on non-objective measures of sleep disordered breathing, thus limiting the ability to draw conclusions on the directionality of the association.6-8 It remains unclear whether sleep disordered breathing precedes cognitive impairment in community-dwelling elderly individuals.

Given the high prevalence and significant morbidity associated with both sleep disordered breathing and cognitive impairment in older populations, establishing whether a prospective association exists between SDB and cognition is important. This is especially important because effective treatments for sleep disordered breathing exist.9 Furthermore, investigation of the mechanisms through which these conditions are related can provide clues for the refinement and development of treatment and prevention strategies. Each of the two chief characteristics of sleep disordered breathing —sleep fragmentation and hypoxia—have possible negative effects on cognitive function, yet neither has been carefully investigated in large longitudinal studies.

We prospectively examined the association between prevalent sleep disordered breathing measured objectively with polysomnography and subsequent diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia to look for evidence that sleep disordered breathing precedes cognitive impairment and assess possible mechanisms (hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, or sleep duration) to explain this association.

METHODS

Study Population

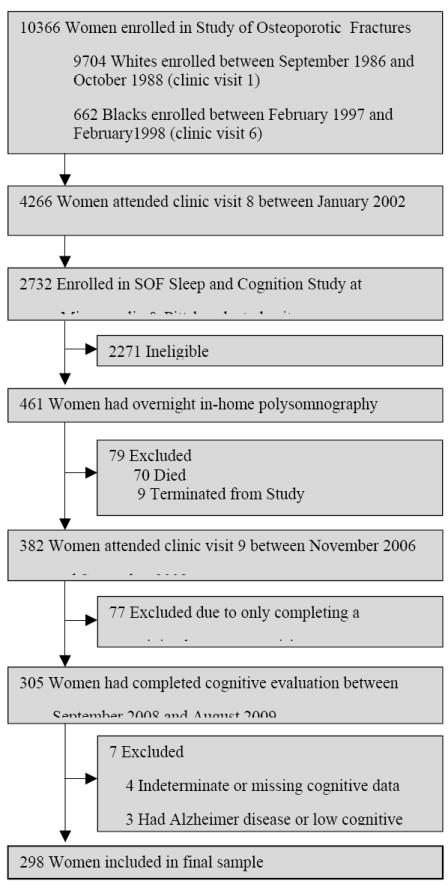

We studied participants enrolled in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF), a multisite cohort study of community-dwelling women.10 Women who were aged 65 years or older and able to walk unassisted were recruited from population-based listings in four US areas: Baltimore County, Maryland; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; and the Monongahela Valley, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A total of 9,704 white women were enrolled between September 1986 and October 1988, and 662 black women were enrolled between February 1997 and February 1998. (Figure 1) At each site, the institutional review boards approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Figure 1.

Progression of Patients Through the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures’ Sleep and Cognition Study

At the eighth clinic visit (January 2002 to April 2004) an ancillary study, the SOF Sleep and Cognition Study, was initiated at two clinical centers (Minneapolis and Pittsburgh, n=2732).6 This eighth clinic visit of SOF is the “baseline” visit for the Sleep and Cognition Study. Eligible women were invited to participate in the polysomnography (PSG) substudy. Potential participants were excluded if they reported use of a pressure mask (continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway pressure) or mouthpiece for snoring or sleep apnea during the past 3 months. In addition, participants were excluded if they had an open tracheostomy or reported regular use of oxygen therapy during sleep. Unattended overnight in-home polysomnography was completed in a convenience sample of 461 women.

Between November 2006 and September 2008 (ninth clinic visit, median follow up = 4.7 years, range 3.2-6.2 years), 305 of the 461 participants with polysomnography completed a battery of neuropsychological tests and subsequently had their cognitive status determined between September 2008 and August 2009. Of the 156 women who did not attend the ninth clinic visit, 70 had died and 9 were previously terminated from the study. Seventy seven women were excluded because they completed a minimal assessment visit (frequently collected by telephone). Of the 305 women who had a cognitive evaluation, 4 had missing or indeterminate cognitive data and were excluded and 3 women who screened positive for cognitive impairment (physician’s diagnosis of Alzheimer disease reported or low cognitive test score) also were excluded. Our analytic cohort is comprised of the 298 women with complete polysomnography data and cognitive assessment.

Polysomnography

Polysomnography data was collected in participants’ homes using the Compumedics Siesta Unit (Abbotsville, Australia). Channels included 2 central electroencephalograms (EEG), bilateral electrooculogram (EOG), chin electromyogram (EMG), thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort, airflow (using nasal-oral thermocouple and nasal pressure recording), finger pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram (ECG), body position, and bilateral piezoelectric sensors to detect leg movements. Data were evaluated by trained technicians, and sleep stage was assessed in 30-second epochs according to standard criteria.11 Apneas (complete cessation of airflow) and hypopneas (discernible [> 30%] reduction in airflow) were defined if occurring for 10 seconds or longer and accompanied by a 3% or greater oxygen desaturation. Arousals from sleep were defined as an abrupt shift in EEG frequency of 3 seconds or longer; arousals during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep required an increase in chin EMG activity.

Sleep disordered breathing was measured by the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI; number of apnea plus hypopnea events per hour of sleep), and prevalent sleep disordered breathing coded as apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or more events per hour.12 Calculated variables used as indices of hypoxia included the oxygen desaturation index (ODI), defined as number of oxygen desaturations ≥ 3% per hour of sleep and coded as ≥ 15 or < 15 events per hour;12 the percentage of sleep time with oxygen saturation (SaO2) < 90% coded as ≥ 1% of sleep time or < 1% sleep time with SaO2 < 90%; and the percentage of sleep time in apnea or hypopnea (>3% of oxygen desaturation coded into tertiles). Calculated variables of sleep fragmentation included arousal index (AI) defined as number of arousals per hour of sleep and minutes of wake after sleep onset (WASO) (both coded into tertiles). Sleep duration was measured as the total sleep time (TST) coded into tertile.

Cognitive Assessment

The shortened Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),13 a test of global cognition, and a modified version of Trails B,14 a test of executive function, were administered at all clinic visits including at baseline (eighth clinic visit). At the follow-up visit (approximately 5 years later), an expanded neuropsychological test battery was administered to women participating in the Sleep and Cognition ancillary study. This battery included Trails B, the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS),15 a 100-point extended version of the MMSE that has superior accuracy for dementia screening,16 the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) (Second Edition Short Form),17 Digit Span (from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised),18 and category and verbal fluency tests.19

Cognitive impairment was determined in a 2-step process.20 First, women were screened for 1 or more of the following criteria: 1) score <88 on the 3MS; 2) score <4 on the CVLT delayed recall; 3) score ≥3.6 on the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly;21 4) previous diagnosis of dementia or use of medication for dementia; or 5) nursing home residence. The women who screened positive had their clinical cognitive status adjudicated by a panel of clinical experts who were blinded to the women’s sleep disordered breathing status. The panel reviewed all cognitive, self reported medical history, and functional data. The women who screened negative were considered cognitively normal. A diagnosis of dementia was made based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria.22 MCI was diagnosed using the modified criteria by Peterson et al 23, 24 (data on subjective memory loss was available for some but not all women) which requires a cognitive impairment that is insufficient to meet criteria for dementia and reflects generally intact function.

Other measures

Participants completed a questionnaire assessment of medical history and underwent a brief physical examination at each study visit. Information on age, race, height and weight, educational attainment, self-reported current smoking, self-reported history of a physician’s diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and stroke were included in the analyses as potential confounders. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. A score of 6 or greater on the Geriatric Depression Scale was used to define high depressive symptoms. Current use of medication was verified by examination of pill bottles; medications were categorized using a computerized coding dictionary according to brand or generic names.25 Drug categories included anti-depressants, benzodiazepines, and non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics.

Statistical Analysis

We first determined median polysomnography parameters. To compare baseline characteristics of women with sleep disordered breathing with those without sleep disordered breathing, we used chi-square and t-tests. We then calculated unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression models to examine the association between sleep disordered breathing and MCI/dementia. Multivariate models were adjusted for age, race, BMI, education, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, antidepressant use, benzodiazepine use, and non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics use; additional models were adjusted for cognitive test scores at baseline. Next, we examined models with individual measures of hypoxia and disordered breathing, sleep fragmentation, or sleep duration as predictors of cognitive impairment.

Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. A p-value of less than .05 was considered significant and 2-sided tests were used. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Of the 298 women studied, most were white (n=269; 90.3%), had a mean age of 82.3 years, and 30.2% graduated from high school and attended college. Compared with the other women who attended the ninth clinic visit but did not participate in our substudy (n=1430), the 298 women who participated were younger, had slightly greater BMIs, and slightly better cognitive scores at the eighth clinic visit (mean age: 82.3 years vs 83.5 years, respectively p<0.001; mean BMI: 28.3 kg/m2 vs 27.1 kg/m2, p<0.001; mean MMSE score: 25.0 vs 24.5, p=0.002 and mean Trails B score: 127.6 vs 159.2, p<0.001), but did not differ on other characteristics. The median apnea-hypopnea index and oxygen desaturation index were 10 and 14.5 events per hour of sleep respectively. Among the 298 women, 105 (35.2%) met criteria for sleep disordered breathing with an apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or more events per hour. Women with and without sleep disordered breathing did not differ on baseline characteristics (Table 1). Median total sleep time was 6.0 hours with a median of 18.0 arousals per hour of sleep and median wake after sleep onset of 79.0 minutes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by sleep disordered breathing status (N=298)

| Characteristic, mean ± SD or N (%) | No SDB (n= 193) | Prevalent SDB (n=105) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 82.1 ± 3.2 | 82.6 ± 3.1 | 0.24 |

| White | 173 (90) | 96.0 (91) | 0.62 |

| Education >high school | 60 (31) | 30 (29) | 0.65 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.9 ± 4.8 | 28.7 ± 5.3 | 0.20 |

| Prevalent diabetes | 19 (10) | 17 (16) | 0.11 |

| Prevalent hypertension | 116 (60) | 69 (66) | 0.34 |

| History of stroke | 25 (13) | 11 (11) | 0.53 |

| High number of depressive symptoms | 23 (12) | 9 (9) | 0.37 |

| Current smokinga | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.17 |

| Current Medication use | |||

| Antidepressants | 16 (8) | 8 (8) | 0.84 |

| Benzodiazepines | 14 (7) | 9 (9) | 0.68 |

| Non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 0.71 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | 24.9 (1.2) | 25.1 (1.1) | 0.22 |

| Trails B | 130.1 (54.8) | 122.9 (52.1) | 0.48 |

Fisher’s exact test

Table 2.

Sleep disordered breathing, sleep fragmentation, and sleep duration measures (N=298)

| Median | Interquartile Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Apnea-Hypopnea Index, events/hour of sleep | 10.0 | 5.2 - 19.5 |

| Hypoxia/Disordered Breathing Measures | ||

| Oxygen Desaturation Index, events/hour of sleep | 14.5 | 8.1 - 23.6 |

| Sleep time with SaO2 < 90%, % | 0.5 | 0.1 - 2.8 |

| Sleep time in apnea/hypopnea with >3% desaturation, % | 4.2 | 1.4 - 9.2 |

| Sleep Fragmentation Measures | ||

| Arousal Index, arousals/hour sleep | 18.0 | 12.4 - 26.3 |

| Wake after sleep onset, minutes | 79.0 | 52.0 - 125.0 |

| Sleep Duration Measure | ||

| Total sleep time, hours | 6.0 | 5.3 - 6.7 |

After a mean of 4.7 years of follow-up, 107 (35.9%) women developed MCI or dementia (MCI: n=60 (20.1%), dementia: 47 (15.8%) developed dementia. Women who developed MCI/dementia had lower baseline scores on cognitive tests but otherwise did not differ on baseline characteristics from those who did not develop cognitive impairment or dementia. Forty-seven women (44.8%) with prevalent sleep disordered breathing developed MCI/dementia compared with 31.1% (60/193) of those without SDB (p=0.02).

The presence of sleep disordered breathing was associated with an increased odds of subsequent MCI/dementia (OR=1.80, 95% CI 1.10 − 2.93). Adjustment for age, race, BMI, education, smoking, diabetes, antidepressant use, benzodiazepine use, and use of non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics led to similar results (OR=1.85, 95% CI 1.11-3.08). Additional adjustment for baseline cognitive test scores strengthened the association (OR=2.36, 95% CI 1.34-4.13). When mild cognitive impairment and dementia were analyzed separately, results were consistent with the combined analysis, although with reduced power to detect a difference (eTable at http://www.jama.com).

We also investigated the relationship of hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, and a measure of sleep duration on risk for MCI/dementia. Two measures of hypoxia, an oxygen desaturation index of ≥15 and a high percentage of total sleep time (>7.0%) in apnea or hypopnea, were associated with higher incidence of MCI/dementia (ODI≥15 vs ODI<15: OR=1.67, 95% CI 1.03-2.69 and >7.0% Sleep time in apnea or hypopnea vs ≤7.0%: OR=1.79, 95% CI 1.01-3.20) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia among older women according to hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, or sleep duration measures

| No. (%) with MCI/dementia | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia/Disordered Breathing Measures | |||

| Oxygen Desaturation Index | |||

| <15 events/hr | 46 (43.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥15 events/hr | 60 (56.6) | 1.67 (1.03, 2.69) | 1.71 (1.04, 2.83) |

| Sleep time with SaO2 < 90% | |||

| < 1% sleep time | 64 (59.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥1% sleep time | 43 (40.2) | 0.87 (0.54, 1.41) | 0.83 (0.51, 1.38) |

| Sleep time in apnea/hypopnea (%), tertileb | |||

| Low (0.9, 0.0-2.2) | 31 (29.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mid (4.4, 2.3-7.0) | 31 (29.0) | 1.00 (0.55, 1.82) | 1.16 (0.61, 2.20) |

| High (16.4, 7.0-66.8) | 45 (42.1) | 1.79 (1.01, 3.20) | 2.04 (1.10, 3.78) |

| Sleep Fragmentation Measures | |||

| Arousal Index (arousals/hour), tertile | |||

| Low (10.1, 2.4-14.5) | 44 (41.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mid (18.2, 14.6-22.6) | 30 (28.3) | 0.52 (0.29, 0.94) | 0.54 (0.29, 0.98) |

| High (33.1, 22.6-66.4) | 32 (30.2) | 0.59 (0.34, 1.06) | 0.58 (0.32, 1.07) |

| Wake after sleep onset (minutes), tertile | |||

| Low (40.7, 2.0-61.0) | 31 (29.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mid (82.0, 62.0-105.0) | 32 (29.9) | 1.06 (0.58, 1.94) | 1.17 (0.63, 2.19) |

| High (170.6, 108.0-336.0) | 44 (41.1) | 1.69 (0.95, 3.02) | 1.79 (0.97, 3.29) |

| Sleep Duration Measure | |||

| Total sleep time (minutes), tertile | |||

| Low (269.9, 128.0-330.0) | 41 (38.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mid (358.2, 331.0-385.0) | 29 (27.1) | 0.56 (0.31, 1.01) | 0.58 (0.31, 1.09) |

| High (425.5, 386.0-630.0) | 37 (34.6) | 0.83 (0.47, 1.47) | 0.83 (0.46, 1.51) |

Abbreviations: OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Adjusted for age, race, body mass index, education, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, antidepressant use, benzodiazepine use, and non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics use

(median, range)

Sleep time with an oxygen desaturation of less than 90% was not significantly associated with MCI/dementia. Conversely, no significant association was seen for the sleep fragmentation or sleep duration measures of arousal index, wake after sleep onset, or total sleep time, before or after adjustment for covariates. Measures of hypoxia remained significant even after adjusting for covariates and baseline cognitive test scores (ODI: OR=1.98, 95% CI 1.15-3.43 and Sleep time in apnea/hypopnea: OR=2.32, 95% CI 1.19-4.54).

DISCUSSION

Among older women, sleep disordered breathing was associated with an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment 5-years later. In addition, even after adjusting for demographic risk factors and comorbidities, we found that 2 of 3 indices of hypoxia, but not sleep fragmentation or duration, were associated with incident MCI or dementia, suggesting that hypoxia is a likely mechanism through which sleep disordered breathing increases risk for cognitive impairment.

Prior cross-sectional studies of sleep disordered breathing and cognitive function in elderly populations have reported conflicting results; some investigations have reported associations of sleep disordered breathing with either lower cognitive test scores or dementia6-8 while others have not.26, 27 Such divergent findings could be due to the differences in measurement and definition of sleep disordered breathing or of cognitive impairment. These earlier cross-sectional studies are also limited in establishing the causal pathway of this association. Our investigation is the first, to our knowledge, to report on the longitudinal relationship between sleep disordered breathing and risk of MCI/dementia.

We explored possible mechanisms (hypoxia and sleep fragmentation or duration) through which sleep disordered breathing might increase the risk for cognitive impairment. Sleep itself plays a critical role in the consolidation of long-term memory which occurs during slow-wave sleep.28 While experimental studies have reported inconsistent effects of sleep fragmentation and hypoxia on deficits in neurocognitive performance,29-33 the literature does not extend to the long term effects of sleep on cognition.

In our study, none of the sleep fragmentation or duration measures had a significant association with cognitive impairment after accounting for potential confounders, while the hypoxia measures were consistently associated with MCI/dementia. This suggests that hypoxia is a likely mechanism for this relationship which is supported by recent animal models of chronic hypoxia that demonstrated similar impairments in cognition with possible implications for apolipoprotein E, inflammatory, and regulatory pathways.34 However, it is important to note that because cerebral blood flow may be affected in elderly patients35, other mechanisms such as hypercapnia could also be involved.

In patients with Alzheimer disease, therapeutic trials of treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for sleep disordered breathing have been shown to slow or even improve cognitive impairment.36, 37 Furthermore, a recent investigation of individuals with sleep apnea indicated that treatment with continuous positive airway pressure not only improved cognitive scores, but also increased grey matter volume in the hippocampal and frontal regions.38

To fully evaluate the impact of treatment for sleep disordered breathing in elderly populations, additional trials with larger sample sizes, longer treatment periods, and more diverse populations are required. Of interest, our findings suggest a potential role for supplemental oxygen therapy for sleep disordered breathing in elderly individuals; however, its role requires critical evaluation in intervention studies. In addition, future studies should consider the association of sleep disordered breathing with impairment in specific cognitive domains as well as changes in these variables over time.

Both the oxygen desaturation index and percentage time in apnea or hypopnea were associated with incident cognitive impairment. The oxygen desaturation index is a measurement of intermittent hypoxemia while the time in apnea or hypopnea estimates the proportion of the sleep period during which the respiration consists of apneas and hypopneas. Unlike the apnea-hypopnea index, which is simply a count of apneas plus hypopneas per hour of sleep (can be elevated when breathing disturbances occur frequently but are of brief duration), the percentage of time in apnea or hypopnea reflects both the frequency and duration of breathing disturbances and thus may better reflect sleep-related gas exchange abnormalities than the apnea-hypopnea index.

Percentage of time in oxyhemoglobin desaturation, as measured by sleep time with oxygen saturation of less than 90% in our study, is another measure of sleep-related hypoxemia and was not significantly associated with mild cognitive impairment or dementia; however, it may not reflect the effects of intermittent hypoxemia as well as the other 2 indices of hypoxemia. Studies suggest intermittent hypoxia, rather than continuous hypoxia, is associated with greater risk of oxidative stress and adverse outcomes.39, 40

Although our prospective design with objective measures of sleep disordered breathing and rigorous methods to diagnose cognitive impairment supports the hypothesis that sleep disordered breathing precedes dementia, there are several limitations that warrant consideration. While measurement of polysomnography data in a sleep laboratory over multiple nights is the criterion standard, several studies indicate that polysomnography measures in the home vs in the lab taken during 1 night vs multiple nights are reliable, although misclassification bias is possible.41-43 In this study, polysomnography data was collected in the home for only 1 night so variability in sleep disturbance measures over time may not have been captured. Because the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures cohort is composed of mostly white women, these findings may not be generalizable to men or more ethnically diverse populations. Finally, because women with more severe sleep disordered breathing or cognitive impairment were less likely to survive to the eighth and ninth decades of life, there may be a survival bias in our results, but this would most likely result in an underestimate of the association.

Conclusions

We found that among women with a mean age of 82 years, sleep disordered breathing was associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment. Our results indicate that this relationship seems to be related primarily to measures of hypoxia. Given the high prevalence of both sleep disordered breathing and cognitive impairment among older adults, the possibility of an association between the 2 conditions, even a modest one, has the potential for a large public health impact. Furthermore, the finding that hypoxia and not sleep fragmentation or duration seems to be associated with risk of MCI/dementia provides clues to the mechanisms through which sleep disordered breathing might promote cognitive impairment. The increased risk for cognitive impairment associated with sleep disordered breathing opens a new avenue for additional research on the risk for development of MCI/dementia and exploration of preventive strategies that target sleep quality including sleep disordered breathing.

Acknowledgments

Study funding/Support: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The National Institute on Aging (NIA) provides support under the following grant numbers: AG05407, AR35582, AG05394, AR35584, AR35583, R01 AG005407, R01 AG027576-22, 2 R01 AG005394-22A1, and 2 R01 AG027574-22A1, AG05407, AR35582, AG05394, AR35584, AR35583, AG026720. In addition, this study was supported by NIA AG026720.

Dr. Yaffe is supported in part by NIA grant K24AG031155.

Dr. Spira is supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award NIA 1K01AG033195.

Dr. Ancoli-Israel is supported by NIA grant AG08415.

Role of the Study Sponsor: The National Institute on Aging did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Yaffe had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Yaffe, Laffan, Stone

Acquisition of data: Stone, Ensrud

Analysis and interpretation of data: Yaffe, Laffan, Harrison Litwack, Redline, Spira, Ensrud, Ancoli-Israel

Drafting of the manuscript: Yaffe, Laffan

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Yaffe, Laffan, Redline, Spira, Ensrud, Ancoli-Israel

Statistical analysis: Harrison Litwack

Obtained funding: Stone, Ensrud, Yaffe

Study supervision: Stone, Ensrud

Conflict of Interest/Disclosures:

Dr Yaffe reported that she is a consultant for Novartis Inc; serves on data and safety monitoring boards for Pfizer, Medivation, and the National Institute of Mental Health; is a board member for Beeson Scientific Advisory; has grants pending with the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer Association, the Department of Defense, and the American Health Assistance Foundation; and has received funding for expenses unrelated to the activities listed from the Alzheimer Association, the National Institutes of Health, Beeson Scientific, Japan Geriatrics Society, Wake Forest University, and the State of California Department of Human Services. Dr Laffan reported that she received salary support and was reimbursed for travel to professional society meetings from the National Institutes of Health. Dr Redline reported that her institution received a California Pacific Medical Center subcontract via a National Institutes of Health grant; she is a board member for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine; her institution has received an endowment for a professorship in sleep medicine from Dr Peter Farrell, CEO of RosMed Inc; and has multiple grants pending with the National Institutes of Health on sleep apnea. Dr Spira reported that he has received honoraria as a clinical editor for the International Journal of Sleep and Wakefulness—Primary Care, which receives pharmaceutical industry support. Dr Ancoli-Israel reported that she is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Purdue Pharma LP, sanofi-aventis, and Pfizer and has grants pending with the National Institutes of Health. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O. Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991 Dec;14(6):486–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ip MSM, Lam B, Ng MMT, Lam WK, Tsang KWT, Lam KSL. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is Independently Associated with Insulin Resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Mar 1;165(5):670–676. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2103001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T, Peppard P. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: epidemiologic evidence for a relationship. Sleep. 2000 Jun 15;23(Suppl 4):S122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, et al. Sleep-Disordered Breathing, Glucose Intolerance, and Insulin Resistance. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Sep 15;160(6):521–530. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered Breathing and Cardiovascular Disease. Cross-sectional Results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Jan 1;163(1):19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spira AP, Blackwell T, Stone KL, et al. Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Cognition in Older Women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dealberto MJ, Pajot N, Courbon D, Alperovitch A. Breathing disorders during sleep and cognitive performance in an older community sample: the EVA Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996 Nov;44(11):1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Butters N, Parker L, Kripke DF. Dementia in institutionalized elderly: relation to sleep apnea. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991 Mar;39(3):258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan C, Berthon-Jones M, Issa F, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. The Lancet. 1981;317(8225):862–865. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk Factors for Hip Fracture in White Women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(12):767–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System For Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999 Aug 1;22(5):667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987 Aug;48(8):314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997 Apr;50(4):377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test - (CVLT-II) Second. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms and Commentary. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaffe K, Middleton L, Lui L-Y, et al. Mild cognitive impairment, dementia and subtypes among oldest old women. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(5):631–636. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorm AF, Jacomb PA. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol Med Nov. 1989;19(4):1015–1022. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol Dec. 2001;58(12):1985–1992. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999 Mar;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, Brown SL, Wallace RB, Carbonin P. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10(4):405–411. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foley DJ, Masaki K, White L, Larkin EK, Monjan A, Redline S. Sleep-disordered breathing and cognitive impairment in elderly Japanese-American men. Sleep. 2003 Aug 1;26(5):596–599. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sforza E, Roche F, Thomas-Anterion C, et al. Cognitive function and sleep related breathing disorders in a healthy elderly population: the SYNAPSE study. Sleep. 2010 Apr 1;33(4):515–521. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Born J, Wilhelm I. System consolidation of memory during sleep. Psychological Research. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00426-011-0335-6. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Davis JD, Riggs RL, Byrd D. Neuropsychological sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: A critical review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(05):772–785. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704105134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kingshott RN, Cosway RJ, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. The effect of sleep fragmentation on cognitive processing using computerized topographic brain mapping. J Sleep Res. 2000;9(4):353–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stepanski EJ. The effect of sleep fragmentation on daytime function. Sleep. 2002 May 1;25(3):268–276. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas RJ, Tamisier R, Boucher J, et al. Nocturnal hypoxia exposure with simulated altitude for 14 days does not significantly alter working memory or vigilance in humans. Sleep. 2007 Sep 1;30(9):1195–1203. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss MD, Tamisier R, Boucher J, et al. A pilot study of sleep, cognition, and respiration under 4 weeks of intermittent nocturnal hypoxia in adult humans. Sleep Med. 2009;10(7):739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Row BW. Intermittent hypoxia and cognitive function: implications from chronic animal models. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;618:51–67. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-75434-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Beek AHEA, Claassen JAHR, Rikkert MGMO, Jansen RWMM. Cerebral autoregulation: an overview of current concepts and methodology with special focus on the elderly. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(6):1071–1085. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ancoli-Israel S, Palmer BW, Cooke JR, et al. Cognitive Effects of Treating Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2076–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooke JR, Ayalon L, Palmer BW, et al. Sustained use of CPAP slows deterioration of cognition, sleep, and mood in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and obstructive sleep apnea: a preliminary study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009 Aug 15;5(4):305–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canessa N, Castronovo V, Cappa SF, et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Brain Structural Changes and Neurocognitive Function Before and After Treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0693OC. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dematteis M, Godin-Ribuot D, Arnaud C, et al. Cardiovascular consequences of sleep-disordered breathing: Contribution of animal models to understanding the human disease. ILAR Journal. 2009;50(3):262–281. doi: 10.1093/ilar.50.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drager LF, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. Metabolic consequences of intermittent hypoxia: Relevance to obstructive sleep apnea. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;24(5):843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghegan MD, Angelos PC, Stonebraker AC, Gillespie MB. Laboratory versus Portable Sleep Studies: A Meta-Analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):859–864. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000214866.32050.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iber C, Redline S, Kaplan Gilpin AM, et al. Polysomnography performed in the unattended home versus the attended laboratory setting--Sleep Heart Health Study methodology. Sleep. 2004;27(3):536–540. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quan SF, Griswold ME, Iber C, et al. Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) Research Group: Short-term variability of respiration and sleep during unattended nonlaboratory polysomnography–the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2002;25:843–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]