Abstract

The co-infection of HIV and helminth parasites, such as Schistosoma spp, has increased in sub-Saharan Africa. Many HIV vaccine candidate studies have been completed or are in ongoing clinical trials, but it is not clear how HIV vaccines might affect the course of schistosome infections. In this study, we immunized S. mansoni-infected mice with an efficient DNA vaccine that included HIV gag. Using this model, we found that Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, were highly induced after schistosome infection. Treatment of infected mice with the HIV DNA vaccine resulted in a significant attenuation of this rise in IL-13 expression and an increase in expression of the Th1 cytokine, TNF-α. However, vaccine administration did not significantly influence the expression of IL-4, or IFN-γ, and did not affect T cell proliferative capacity. Interestingly, the IL-4+IFN-γ+ phenotype appears in schistosome-infected mice that received HIV vaccination, and is associated with the expression of transcription factors GATA3+T-bet+ in these mice. These studies indicate that DNA vaccination can have an impact on ongoing chronic infection.

Keywords: schistosome infection, HIV vaccine, Th1 and Th2 responses

Introduction

The causative agents of schistosomiasis are parasitic flatworms of the genus Schistosoma. Schistosomiasis is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting more than 200 million people worldwide and resulting in more than 300,000 deaths annually.1,2 Schistosomes have a complex life cycle, in which cercariae, free-living in fresh water, can penetrate healthy human skin. The schistomules pass several days in the skin then enter the venous circulation and travel through the circulatory system to the heptoportal circulation where they mature into adult worms and mate. Depending on the species, the schistosomes migrate to their final infection site either on the bladder or the intestine where the females begin egg production. These eggs are expelled in the feces or urine. The miracidium, liberated from the egg, seek out snail hosts where they enter a sporocyst stage that eventually results in free-living cercariae that seek out human hosts again.3

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is also a significant global health problem and is estimated to have infected more than 60 million individuals globally. There has been an intense worldwide effort to develop a highly effective vaccine against HIV to stem this epidemic. Indeed, more than 95 clinical trials of different HIV vaccine candidates have been completed4 with modest effects on protection.5 HIV-1 and schistosomiasis are co-endemic in many regions, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where 25 million people are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and an estimated 170 million people are infected with chronic schistosomiasis.6 As a result, the prevalence of co-infected individuals has been shown to reach high proportions.7 Even though an HIV vaccine will be broadly applied for preventing HIV infection, the impact of HIV vaccination on the progression of schistosomiasis in co-infected persons has been questioned.

Schistosome infections are chronic and are characterized immunologically by an early Th1 response that later switches to a Th2-dominated response after the onset of parasite egg production.8 The most serious form of this infection is a life-threatening hepatosplenic disease, which is usually accompanied by severe hepatic and periportal fibrosis. Although Th2 responses seem to have a crucial role in modulating the potentially lethal disease during its initial stages of schistosomiasis, its prolonged Th2 responses have been shown to contribute to the development of hepatic fibrosis and chronic morbidity.9 The main Th2 cytokine that is responsible for fibrosis is IL-13. Thus, schistosome-infected mice in which IL-13 is either absent (IL13−/−),10 ineffective (IL-4 receptor α-chain-knockouts; Il4rα−/−),11 or neutralized by treatment with soluble IL-13Rα2–Fc12 fail to develop the severe hepatic fibrosis that normally occurs during infection, leading to prolonged survival of these mice.10 The finding that IL-13 is able to promote fibrogenesis13-16 might have implications for the possible use of IL-13-blocking therapies in the fibrotic disease. Mediators that are associated with Th1 responses, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-12, TNF and NO can prevent IL-13-mediated fibrosis.16

DNA vaccines have been demonstrated to induce Th1 responses, such as IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNFα.17,18 Our lab has completed a number of studies of HIV DNA vaccines using the macaque model.19-22 We have developed an efficient DNA vaccine that includes HIV gag, and has been shown to induce higher Th1 responses, enhancing the protection against HIV.23,24 Using this model, we wanted to determine the effect of HIV vaccination on schistosome infection. We found that schistosome infection increased the Th2 response (such as high expression of IL-4 and IL-13). But that following HIV vaccination, we observed a decrease in expression of several Th2 cytokines such as IL-13, and an increase of some Th1 cytokines, such as TNFα. Although we found no significant affect on IL-4 and IFN-γ expression, a new phenotype of IL4+IFN-γ+ appeared in the schistosome-infected mice that received HIV vaccination

Results

HIV vaccination decreases expression of SEA-induced IL-13 in schistosome-infected mice

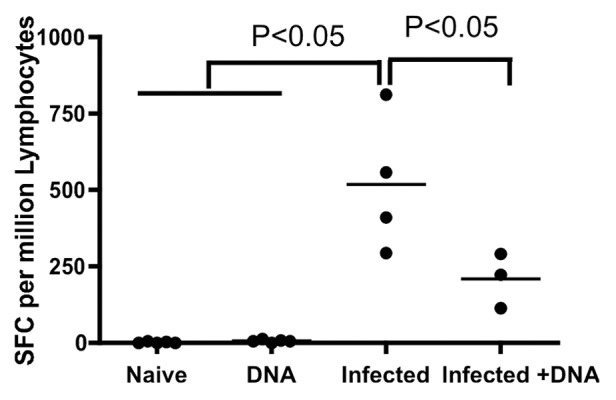

In order to evaluate the impact of HIV vaccination on schistosome-infected mice, mice were divided into four groups: those infected with S. mansoni (Infected group); those uninfected, but immunized with HIV DNA vaccine (DNA group); those immunized with HIV DNA vaccine 8 weeks following S. mansoni infection (Infected + DNA group); and an uninfected negative control group of six mice that was mock-immunized with saline (Naïve group). All mice were sacrificed one week after the last immunization. IL-13 is responsible for fibrosis during schistosomiasis12 and fibrosis itself is ranked as a quantitative tool for assessing the severity of disease. Therefore, we initially assessed S. mansoni soluble egg antigens (SEA)-induced IL-13 expression in all mice by an IL-13 ELISA-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay to test disease severity. Mice in the Infected group showed the highest SEA-specific IL-13 response with an average of 518 spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 spleen lymphocytes (Fig. 1). Treatment with HIV DNA vaccine dramatically reduced the IL-13 response, as the Infected+ DNA group showed an average of 209 spot-forming cells (SFC) per million cells. In contrast, antigen-specific IL-13 secretion was not found in the DNA group or the Naïve group (Fig. 1). These data suggest that HIV vaccination might decrease the severity of fibrosis in schistosome-infected mice.

Figure 1. IL-13 expression one week after last immunization. Spleen lymphocytes were isolated one week after last immunization and SEA-specific IL-13 responses were assessed by standard ELISpot. Individual data of IL-13 producing cells after stimulation with SEA antigen for all mice are displayed. p < 0.05 per the unpaired t test.

Th1 type cytokines are expressed in schistosome-infected mice treated with HIV DNA vaccine

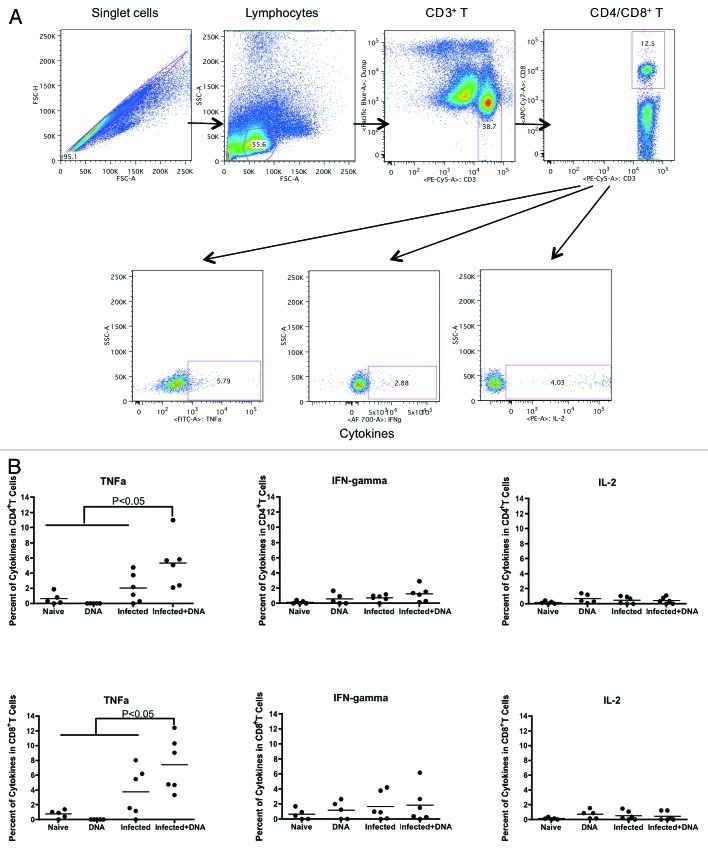

Antigen-specific Th1 responses can lead to reduced hepatic fibrosis.26,27 Hence, we tested for antigen-specific Th1 responses such as production of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α one week following immunization of mice. Fresh lymphocytes isolated from mice one week after the last vaccination were stimulated for 5 h with growth media, antigen or SEB. Following stimulation, cells were washed, stained and fixed. Cytokines were then measured by flow cytometry.

In CD4+ T cells, we observed more TNFα production in schistosome-infected mice that received the HIV DNA vaccine than those that did not (Fig. 2A). Thus, the average percentage of cytokines in CD4+ cells that were TNFα was 5.3% and 2.0% in the Infected + DNA group vs. the infected group, respectively. In contrast, neither IFN-γ nor IL-2 production differed significantly between the two groups (Fig. 2A and data not shown). In CD8+ T cells, we found TNFα production was also significantly higher in the Infected + DNA group compared with the infected only group (Fig. 2B). Again, there was no significant difference in the level of IFN-γ or IL-2 between these two groups (Fig. 2B and data not shown). A small amount of TNFα was also produced in the CD4 and CD8 T cells of both the DNA group and the Naïve group (Fig. 2). In summary, expression of the Th1 cytokine TNFα expression increased significantly in schistosome-infected mice following treatment with HIV DNA vaccine.

Figure 2. Th1 cytokine expression one week after last immunization. Fresh lymphocytes from all mice were isolated one week following the final immunization and analyzed for Th1 cytokines, TNFα, IFN-γ and IL-2. (A) Gating strategy shows TNFa, IFN-gamma and IL-2 from CD4+/CD8+ T cells. (B) Cytokines data for SEA (medium alone values subtracted) is enumerated per immunization group and shown for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells. Data was acquired on an LSRI instrument analyzed with flowjo software. *p < 0.05 per the unpaired t test.

T cell proliferative capacity does not increase in schistosome-infected mice following treatment with HIV DNA vaccine

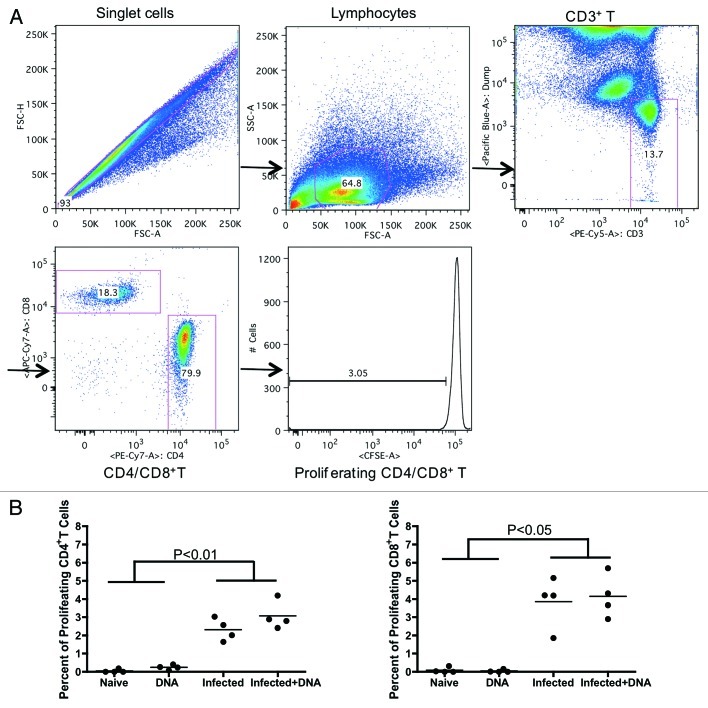

T-cell proliferation may be positively correlated with disease severity in S. hematobium-infected humans.24 We, therefore, chose to investigate the effects of infection and HIV DNA vaccine on the ability of SEA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ effector cells to proliferate. Lymphocytes isolated from mice one week after the last vaccination were incubated with CFSE, washed, and stimulated for 5 d with growth media, S. mansoni soluble egg antigens (SEA) or concanavalin A (conA). Following stimulation, T-cell proliferation was measured by flow cytometry. We found that SEA-specific proliferative responses in CD4+ cells (Fig. 3A) were enhanced in both the Infected group and the Infected + DNA group (average of 2.32% and 3.07%, respectively) compared with the DNA group and Naïve group (average of 0.04% and 0.24%, respectively). However, there was no significant effect of HIV DNA vaccine treatment on proliferation of cells from either of the two infected groups.

Figure 3. Proliferative capacity of antigen-specific T-cells in infected and/or vaccinated animals. Lymphocytes from all mice were isolated one week following the final immunization and analyzed for proliferative capacity. (A) Gating strategy shows proliferative capacity from CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. (B) Proliferative data for SEA antigen (medium alone values subtracted) is enumerated per immunization group and shown for CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells. *p < 0.05 per the unpaired t test.

The proliferative capacity of CD8+ T cells was similar to that of CD4+ T cells, reaching an average of 3.8% in the Infected group and 4.1% in the Infected + DNA (Fig. 3B); as with CD4+ cells, little proliferative response was observed in the DNA group or Naïve group (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that treatment of schistosome-infected mice with the HIV DNA vaccine does not produce significant differences in the SEA-specific proliferative capacity of T cells from schistosome-infected mice. However, S. mansoni infection itself increases SEA-specific proliferative levels.

IL-4+IFN-γ+ and GATA3+Tbet+ phenotypes are induced in schistosome-infected mice treated with the HIV DNA vaccine

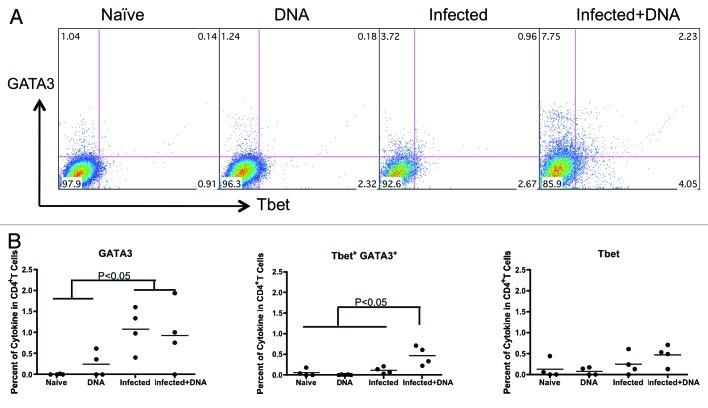

It is well known that schistosomiasis leads to the development of a strong Th2 response27,28 and that the HIV DNA vaccine induces a strong Th1 response. To assess the levels of Th1 and Th2 responses in our model, we tested IFN-γ and IL-4 expression by flow cytometry. Fresh lymphocytes isolated from infected and uninfected mice one week after the last vaccination were stimulated for 5 h with antigen and stained with antibodies. Following staining, the expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 was measured by flow cytometry. We found that the two schistosome-infected groups each produced more IL-4 (average of 1.27% in the Infected group and 1.14% in the Infected+DNA group, respectively) than the two un-infected groups (0.28% in the DNA group and 0.22% in the Naïve group, respectively; (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4). Nonetheless, there is no significant difference between the two schistosome-infected groups in IL-4 production. Similarly, we found no difference in expression of IFN-γ between the groups. Notably, however, schistosome-infected mice that were immunized with the HIV DNA vaccine showed significantly more IFN-γ+IL-4+ cells than any of the other groups (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The balance of Th1 and Th2 responses induced by schistosome infection and followed HIV vaccination. Lymphocytes isolated from one week after the last immunization were stimulated with antigen for 5 h and stained with surface and inner antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Expression of Th2 and Th1 cytokines, IL-4 and IFN-γ, in CD4+ T cells from one representative animal in each group. (B) Cytokine expression for antigen stimulation (medium alone values subtracted) is enumerated per immunization group and shown for IL-4, IFN-gamma and IFN-gamma+IL-4+. *p < 0.05 per the unpaired t test.

In addition, we tested the transcription factors, GATA-3 and T-bet, which control Th2 and Th1 differentiation.29 We detected a significantly higher percentage of GATA-3 in the two schistosome-infected groups (average 1.08% in the infected group and 0.93% in the Infected+ DNA group, respectively) compared with the DNA only group (average 0.25%) and the Naïve group (0.005%) (Fig. 5). In contrast, there was no difference in the percentage of T-bet among the four groups (Fig. 5). However, double-positive GATA3+T-bet+ CD4 T cells in the infected + DNA group was significantly higher than that of the other groups (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results demonstrate that S. mansoni infection can induce strong IL-4 expression in mice, which does not significantly decrease following HIV DNA vaccination. Furthermore, administration of HIV DNA vaccine to infected mice induces an increase in IL-4+IFN-g+ T cells, as well as increased GATA3+T-bet+ expression.

Figure 5. Transcription factors, GATA-3 and T-bet, expression in mice with schistosome infection and followed HIV vaccination. Lymphocytes isolated from one week after last immunization were stimulated with antigen for 5 h and stained with surface and inner antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) The expression of transcription factor GATA-3 and T-bet in CD4+ T cells from one representative mice in each group. (B) The transcription factors’ expression for antigen stimulation (medium alone values subtracted) is enumerated per immunization group and shown for GATA-3, T-bet and GATA-3+ T-bet+. *p < 0.05 per the unpaired t test.

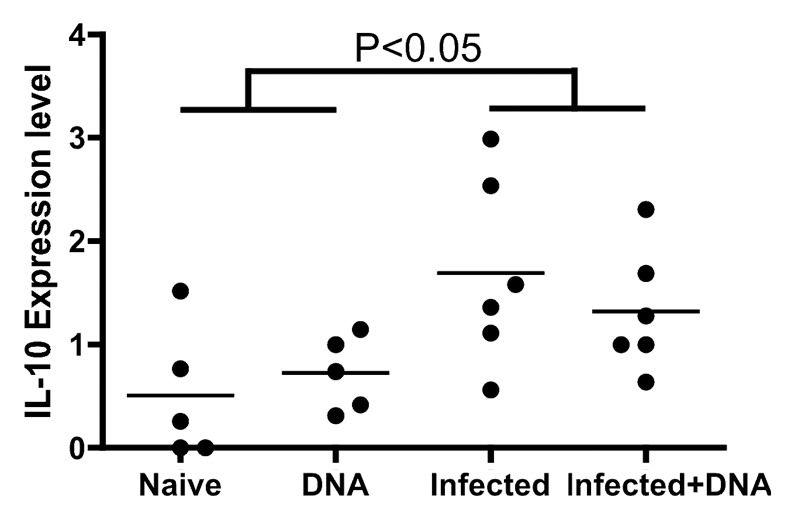

IL-10 plays a role in regulating the Th2 and Th1 response in schistosome infection and HIV DNA vaccination

Evidence suggests that IL-10 is important in regulating schistosomiasis,30 and may play a role blocking development of resistance to reinfection.31 To investigate the potential role of IL-10 in balancing Th1 and Th2 cells following HIV vaccination of schistosome-infected mice, we tested the expression of IL-10 in infected mice one week following the last immunization with the vaccine. Fresh spleen lymphocytes from mice were stimulated with antigen for 5 h and stained with surface antibodies. IL-10 levels were then analyzed with flow cytometry. We observed that IL-10 expression levels reached 1.69% and 1.32% in the Infected group and the Infected + DNA group, respectively, significantly higher than that found in the Naïve group and DNA group (Fig. 6). However, treatment with the HIV DNA vaccine showed no significant effect on IL-10 expression in the schistosome-infected mice (Fig. 6). Thus, levels of IL-10 in schistosome-infected mice are not altered by HIV DNA vaccination, indicating that IL-10 may continue to play an important role in regulating the immune balance in infected mice treated with the vaccine.

Figure 6. IL-10 regulated the balance of Th1 and Th2 induced by schistosome infection and followed HIV vaccination. Lymphocytes isolated from one week after last immunization were stimulated, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry. IL-10 expression in CD4+ T cells is enumerated per immunization group. *p < 0.05 per the unpaired t test.

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated the effect of HIV DNA vaccination on schistosomiasis, using single-cell analyses of key cytokines and transcription factors. We find that the Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13, are elevated after schistosome infection, but that treatment of infected mice with HIV DNA vaccine produces a decrease in IL-13 levels. We also find that the IL-4+IFN-γ+ phenotype is significantly increased in the Infected + DNA group, suggesting that the Th2 and Th1 cell functions of this phenotypic group may play a crucial role in preventing fatal immunopathology and establishing a protective antiviral response upon HIV infection. Finally, we observe high levels of Il-10 induced in the S. mansoni-infected mice, and those high levels are not altered by vaccination.

How the host immune system responds to schistosome infection determines in large part the balance between protective immunity (health) and immunopathology (morbidity).8 It is therefore important that Th1 and Th2 responses are balanced during schistosome infections. Th2-type responses are typically characterized by increases in the levels of IL-4 and other Th2-type cytokines (including IL- 5, IL- 9, IL- 13 and IL- 21), and the main Th2 cytokine that is responsible for fibrosis in schistosomiasis is IL-13.10 In contrast, the HIV DNA vaccine induces high expression of Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNFα,17,22 which can suppress the Th2 response. In infected Il4−/− mice, the severe disease that is observed is not related to increased parasitic burden, but, rather, to the immunological consequences of the absence of Th2 cytokines.32 Our study confirms that schistosome infection induces a strong, antigen-specific Th2 response, resulting in secretion of high levels of IL-4 and IL-13 (Figs. 1 and 4). HIV DNA vaccination of infected mice significantly reduces this IL-13 expression and enhances expression of the Th1 cytokine TNFα. However, the vaccine has no significant influence on IL-4 or IFN-γ expression or on T cell proliferation capacity (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). These results suggest that balance of Th1 and Th2 responses to HIV DNA vaccination may be modulated by effects of parasitic infection such as fibrosis.

IL-10 appears to play an important regulatory role in schistosomiasis, preventing the development of excessive Th1- and Th2-mediated pathologies. Hoffmann and colleagues clearly demonstrated that in schistosome-infected mice, IL-10 significantly suppressed type 1 and type 2 cytokines’ development in IL-4-- and IL-12--deficient mice, respectively, and thereby impeded the development of severe egg-induced pathology in the single cytokine-deficient animals.33 To further define the contribution of IL-10 in persistent infections, Hesse generated the IL-10/recombination-activating gene (RAG)2-deficient mice and demonstrated that innate effectors and regulatory T cells producing IL-10 cooperate to reduce morbidity and prolong survival in schistosomiasis.34 Our data also show high IL-10 expression in schistosome-infected mice compared with uninfected mice (Fig. 6), with no significant effect of treatment with HIV DNA vaccine. These data suggest that the induction of IL-10 by schistosome infection may regulate The responses and limit the pathogenenic consequences of schistosomiasis. In addition, recent data have begun to define the function of IL-10 in B cells during schistosomiasis. Van der Vlugt and colleagues pointed out that schistosomes have the capacity to drive the development of IL-10-producing regulatory CD1dhi B cells in both mice and humans.35 Furthermore, these B cells are instrumental in reducing experimental allergic inflammation in mice.35 Fairfax’s data suggested that during chronic schistosomiasis, IL-10 promotes the development of a population of B cells within the liver that is responsible for minimizing inflammation and preventing the development of disease in the lungs.36 On the other hand, IL-10 appears to block development of resistance to re-infection with S. mansoni.31 IL-10 is likely to play other important roles in the regulation of disease, and further studies are underway.

Interestingly, a stable IL-4+IFN-γ+ cell subset induced by schistosome infection and HIV DNA vaccination may combine Th2 and Th1 cell functions in the murine model. Current T cell differentiation models invoke separate Th2 and Th1 lineages governed by the lineage-specifying transcription factor GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA-3) and T-box-containing protein (T-bet). The transcription factor GATA-3 controls the development of the Th2 cell lineage that is characterized by the secretion of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 which are critical for immunity against helminths and other extracellular pathogens.37,38 T-bet expressed in T cells is the master regulator of the Th1 differentiation program associated with the production of IFN-γ required for efficient immune responses against intracellular pathogens.39 Hegazy et al. demonstrated that infection with Th1 cell-promoting lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) reprogrammed stably committed GATA-3+ Th2 cells to adopt a GATA-3+T-bet+ and IL-4+IFN-γ+ “Th2+1” phenotype that combined Th2 and Th1 cell function. Because T-bet protects against exacerbation of schistosome egg-induced immunopathology,40 the induction of the GATA-3+Tbet+ subset in our study may play a protective role against schistosome-induced pathology. However, there was no high T-bet expression induced in the Infected + DNA group in our study. More work, such as changing the dose of vaccine, will be done to attempt to enhance T-bet induction in the future. In addition, it is not clear that if these phenotypes will appear and how to work in the HIV peptides stimulation. These studies are underway.

Materials and Methods

Animals and parasite infections

Female Swiss Webster mice, both uninfected and those infected with 25–30 S. mansoni cercariae (NMRI strain), were obtained from the NIAID Schistosomiasis Resource Center at the Biomedical Research Institute in Rockville, MD. This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the US, National Institutes of Health. Animal handling and experimental procedures were undertaken in compliance with the University of Pennsylvania's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines (Animal Welfare Assurance Number: A3079–01; IACUC protocol number 802655).

DNA vaccination

The HIV DNA vaccine used in this study expressed the modified HIV gag4Y as described.23 Mice were vaccinated twice, two weeks apart beginning 8 weeks after schistosome infection. These mice were sacrificed one week after the last vaccination. Single-cell suspensions of spleen lymphocytes were prepared by pushing lymphoid organs through a sterile 40 μm pore size nylon mesh.

Antigens: S. mansoni soluble egg antigens (SEA)

Soluble egg antigens (SEA) used in the study was prepared as described previously.25 Briefly, livers isolated from S. mansoni-infected mice at 7–8 weeks post infection were minced with scissors in 1.2% NaCl and passed through a crude sieve. The filtrate was then passed through a series of sieves with decreasing pore size and finally eggs were collected from the top sieve (45 μm). To collect the mature eggs, a repeated swirling technique was employed and eggs were washed with several volumes of 1.2% NaCl solution. After purification, eggs were suspended in ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and homogenized with a polytron homogenizer (PT1200 E) at 4°C. Following ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × gmax for 1 h at 4°C, the crude supernatant was sterilized by passing it through a 0.2 μm filter. The protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Fermentas) and the final supernatant was stored at -80°C until further use.

Enzyme linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) assay for IL-13

ELISpot assays using IL-13 reagents (R&D) and nitrocellulose plates (Millipore) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. A positive response was defined as greater than 50 spot forming cells (SFC) per million lymphocytes. Each sample was assayed in triplicate with antigen.

T cell proliferation

Fresh mouse spleen lymphocytes were incubated with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (5 μmol/l) for 8 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed and incubated with medium alone (negative control), antigen at a concentration of 5 μg/ml, or Concanavalin A (ConA; 5 μg/ml, positive control) for 5 d at 37°C in 96-well plates. Cultures without antigen were used to determine the background proliferative responses. The lymphocytes were then immunostained with the following mAbs: anti-CD3 PE-Cy5, anti-CD4 Pac Orange, anti-CD8 APC-Cy7 (all BD Biosciences). Stained cells were washed in PBS, fixed (Cell-Fix), and then acquired on an LSRI instrument using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Fresh PBMCs were incubated with antigen for 5 h at 37°C. A negative control (medium alone) and S.mansoni antigen, [soluble egg antigens (SEA), 5 μg/ml] and positive control [Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB), 1 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich] was included in each assay. Following incubation, the cells were washed and stained with surface antibodies: CD4 (Pac Orange), CD3 (PE-Cy5) and CD8 (APC-Cy7) (all BD Biosciences). Cells were then washed, fixed and permeated using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD PharMingen) according to its instructions. After fixation, the cells were stained with antibodies against intracellular markers IFN-γ (Alexa Fluor-700), TNF-α (FITC), IL-2 (PE) and IL-10 (APC) or IFN-γ (Alexa Fluor-700), IL-4 (PE-Cy7), T-bet (Percp-cy5.5) and GATA-3 (PE) (all BD Biosciences). These cells were washed and fixed with PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde. Stained and fixed cells were acquired on an LSRI instrument using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Statistics

For comparisons of IL-13 ELISpots, T cell proliferation, intracellular cytokine staining, and regulatory T cell level, two tailed t-tests were performed using Graphpad Prism Software. P values that were < 0.05 were considered a significant difference.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants 5R01A1071886–04 (to J.D.B.) and R01 AI073660 and R21 AI082390 (to R.M.G.). J.Y. performed research and generated the data presented and wrote the paper. A.D., and T. A., performed research in part, R.S.K provided SEA, R.M.G. advised on working with schistosome-infected mice and reviewed the manuscript and J.D.B. designed the experiment and oversaw the project. We thank Fred Lewis and the NIAID Schistosome Resource Center for supplying the schistosome-infected mice.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/22142

Reference

- 1.Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ, Bethony JM, King CH, Pearce EJ, Jacobson J. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1311–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI34261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Werf MJ, de Vlas SJ, Brooker S, Looman CW, Nagelkerke NJ, Habbema JD, et al. Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Trop. 2003;86:125–39. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabel GJ. Mapping the future of HIV vaccines. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:482–4. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, et al. MOPH-TAVEG Investigators Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2209–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chitsulo L, Loverde P, Engels D. Schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:12–3. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kallestrup P, Zinyama R, Gomo E, Butterworth AE, van Dam GJ, Erikstrup C, et al. Schistosomiasis and HIV-1 infection in rural Zimbabwe: implications of coinfection for excretion of eggs. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1311–20. doi: 10.1086/428907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheever AW, Hoffmann KF, Wynn TA. Immunopathology of schistosomiasis mansoni in mice and men. Immunol Today. 2000;21:465–6. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(00)01626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallon PG, Richardson EJ, McKenzie GJ, McKenzie AN. Schistosome infection of transgenic mice defines distinct and contrasting pathogenic roles for IL-4 and IL-13: IL-13 is a profibrotic agent. J Immunol. 2000;164:2585–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jankovic D, Kullberg MC, Noben-Trauth N, Caspar P, Ward JM, Cheever AW, et al. Schistosome-infected IL-4 receptor knockout (KO) mice, in contrast to IL-4 KO mice, fail to develop granulomatous pathology while maintaining the same lymphokine expression profile. J Immunol. 1999;163:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiaramonte MG, Donaldson DD, Cheever AW, Wynn TA. An IL-13 inhibitor blocks the development of hepatic fibrosis during a T-helper type 2-dominated inflammatory response. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:777–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI7325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modolell M, Corraliza IM, Link F, Soler G, Eichmann K. Reciprocal regulation of the nitric oxide synthase/arginase balance in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages by TH1 and TH2 cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1101–4. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesse M, Cheever AW, Jankovic D, Wynn TA. NOS-2 mediates the protective anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of the Th1-inducing adjuvant, IL-12, in a Th2 model of granulomatous disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:945–55. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64607-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Lanone S, Wang X, Koteliansky V, et al. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor beta(1) J Exp Med. 2001;194:809–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesse M, Modolell M, La Flamme AC, Schito M, Fuentes JM, Cheever AW, et al. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J Immunol. 2001;167:6533–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin J, Dai A, Lecureux J, Arango T, Kutzler MA, Yan J, et al. High antibody and cellular responses induced to HIV-1 clade C envelope following DNA vaccines delivered by electroporation. Vaccine. 2011;29:6763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belisle SE, Yin J, Shedlock DJ, Dai A, Yan J, Hirao L, et al. Long-term programming of antigen-specific immunity from gene expression signatures in the PBMC of rhesus macaques immunized with an SIV DNA vaccine. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirao LA, Wu L, Satishchandran A, Khan AS, Draghia-Akli R, Finnefrock AC, et al. Comparative analysis of immune responses induced by vaccination with SIV antigens by recombinant Ad5 vector or plasmid DNA in rhesus macaques. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1568–76. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin J, Dai A, Shen A, Lecureux J, Lewis MG, Boyer JD. Viral reservoir is suppressed but not eliminated by CD8 vaccine specific lymphocytes. Vaccine. 2010;28:1924–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan J, Hokey DA, Morrow MP, Corbitt N, Harris K, Harris D, et al. Novel SIVmac DNA vaccines encoding Env, Pol and Gag consensus proteins elicit strong cellular immune responses in cynomolgus macaques. Vaccine. 2009;27:3260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin J, Dai A, Kutzler MA, Shen A, Lecureux J, Lewis MG, et al. Sustained suppression of SHIV89.6P replication in macaques by vaccine-induced CD8+ memory T cells. AIDS. 2008;22:1739–48. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830efdae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirao LA, Wu L, Khan AS, Satishchandran A, Draghia-Akli R, Weiner DB. Intradermal/subcutaneous immunization by electroporation improves plasmid vaccine delivery and potency in pigs and rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:440–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrow MP, Pankhong P, Laddy DJ, Schoenly KA, Yan J, Cisper N, et al. Comparative ability of IL-12 and IL-28B to regulate Treg populations and enhance adaptive cellular immunity. Blood. 2009;113:5868–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coligan JEKA, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W, Coico R, eds. (1998) Lewis FA Schistosomiasis Current Protocols in Immunology: pp 19.11.11-19.11.28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wynn TA, Cheever AW, Jankovic D, Poindexter RW, Caspar P, Lewis FA, et al. An IL-12-based vaccination method for preventing fibrosis induced by schistosome infection. Nature. 1995;376:594–6. doi: 10.1038/376594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutitzky LI, Hernandez HJ, Stadecker MJ. Th1-polarizing immunization with egg antigens correlates with severe exacerbation of immunopathology and death in schistosome infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231258498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grzych JM, Pearce E, Cheever A, Caulada ZA, Caspar P, Heiny S, et al. Egg deposition is the major stimulus for the production of Th2 cytokines in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. J Immunol. 1991;146:1322–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenner RG, Townsend MJ, Jackson I, Sun K, Bouwman RD, Young RA, et al. The transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 control alternative pathways of T-cell differentiation through a shared set of target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17876–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Biggelaar AH, van Ree R, Rodrigues LC, Lell B, Deelder AM, Kremsner PG, et al. Decreased atopy in children infected with Schistosoma haematobium: a role for parasite-induced interleukin-10. Lancet. 2000;356:1723–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson MS, Cheever AW, White SD, Thompson RW, Wynn TA. IL-10 blocks the development of resistance to re-infection with Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002171. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Flamme AC, Patton EA, Bauman B, Pearce EJ. IL-4 plays a crucial role in regulating oxidative damage in the liver during schistosomiasis. J Immunol. 2001;166:1903–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffmann KF, Cheever AW, Wynn TA. IL-10 and the dangers of immune polarization: excessive type 1 and type 2 cytokine responses induce distinct forms of lethal immunopathology in murine schistosomiasis. J Immunol. 2000;164:6406–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hesse M, Piccirillo CA, Belkaid Y, Prufer J, Mentink-Kane M, Leusink M, et al. The pathogenesis of schistosomiasis is controlled by cooperating IL-10-producing innate effector and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3157–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Vlugt LE, Labuda LA, Ozir-Fazalalikhan A, Lievers E, Gloudemans AK, Liu KY, et al. Schistosomes induce regulatory features in human and mouse CD1d(hi) B cells: inhibition of allergic inflammation by IL-10 and regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fairfax KC, Amiel E, King IL, Freitas TC, Mohrs M, Pearce EJ. IL-10R blockade during chronic schistosomiasis mansoni results in the loss of B cells from the liver and the development of severe pulmonary disease. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002490. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang DH, Cohn L, Ray P, Bottomly K, Ray A. Transcription factor GATA-3 is differentially expressed in murine Th1 and Th2 cells and controls Th2-specific expression of the interleukin-5 gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21597–603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–96. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–69. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutitzky LI, Smith PM, Stadecker MJ. T-bet protects against exacerbation of schistosome egg-induced immunopathology by regulating Th17-mediated inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2470–81. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]