Abstract

Macrophages play a complex role in tumor progression since they can exert both tumor-preventing (M1 macrophages) and tumor-promoting (M2 macrophages) activities. In colorectal carcinoma (CRC), at odds to many other cancers, macrophage infiltration has been correlated with an improved patient survival. In a recent study, we have evaluated the distribution of M1 and M2 macrophage subtypes in CRC and their impact on patient prognosis.

Keywords: CpG island methylator phenotype, colorectal cancer, macrophage subtypes, microsatellite instability, prognosis

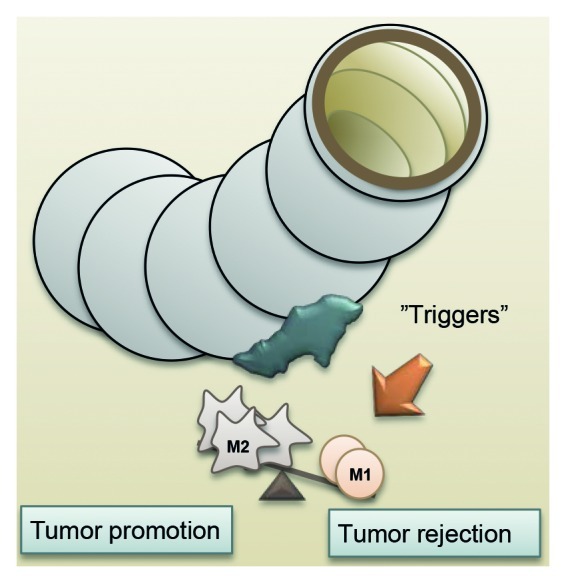

The immune contexture, a suggested collegial name for the sum of the location, density and functional orientation of immune cells, plays multiple important roles in tumor progression and hence critically influences patient prognosis.1 The work on inflammatory processes in human cancers has allowed for the identification of components of the immune system that can be both beneficial and detrimental for a growing tumor. One of such components are macrophages, playing important functions in both innate and adaptive immune responses. Macrophages have been shown to adopt various phenotypes, mainly depending on the environment in which they are found, and there are many examples of macrophage-polarizing events during tumor progression, including the secretion of tumor-derived mediators, hypoxic and necrotic factors, tissue damage, as well as influences from other immune cells and stromal components.2 The role of macrophages in tumor progression has been shown to be double-edged, since these cells can both promote tumor rejection (M1 macrophages) and stimulate tumor growth (M2 macrophages). In brief, pro-inflammatory, or classically activated M1 macrophages, exerting important functions in host defense as well as bactericidal and tumoricidal activity, are held against anti-inflammatory, or alternatively activated M2 macrophages, playing important functions in immune regulation, tissue remodeling and tumor progression.3 M1 macrophages are important actors during acute inflammatory reactions, which are generally believed to be resolved by a transition from the M1 to the M2 phenotype, immunosuppression and the initiation of tissue repair.4 If the condition causing inflammation cannot be resolved, as it is the case during the growth of a prevailing tumor, inflammation may become chronic, a setting in which the functions of M2 macrophages predominate. Accordingly, in many human cancers, tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) have been suggested to mainly exhibit an M2-like phenotype and to be associated with worse prognosis.5 This said, we and others have previously shown that macrophage infiltration in colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is associated with improved patient survival, even though a few reports show contradictory results.6,7 In a recent study, we have investigated the distribution of M1 and M2 macrophages in a relatively large cohort of CRC patients (n = 485), to evaluate if the positive prognostic role of macrophages in CRC could be explained by variations in the balance between M1 and M2 macrophage subtypes.8 We used immunohistochemistry to assess the expression of nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2) (also known as iNOS) as a marker for M1 macrophages and the scavenger receptor CD163 as a marker for M2 macrophages. We found a small overlap of M1 and M2 macrophage markers, in accordance with the reported plasticity of macrophages. However, macrophages that highly expressed one of the markers consistently did not express the other, suggesting that these markers indeed can be used to discriminate between macrophages with a predominant M1 or M2 phenotype (and functions). We found that infiltrating M1 macrophages were significantly associated with an improved prognosis in a tumor stage-dependent manner. However, M1 and M2 macrophages were highly correlated with each other, so that tumors robustly infiltrated by M1 macrophages also contained high numbers of M2 macrophages. M2 macrophages were even found to frequently outnumber the M1 macrophages. In addition, no difference in prognosis was found in patients exhibiting different ratios of tumor-infiltrating M1 and M2 macrophages. This suggest that, at least in the CRC setting, the presence and functions of M1 macrophages dominate over the presence and functions of M2 macrophages, provided that the M1/M2 concept holds true during tumor progression. A schematic view of the macrophage response in CRC is found in Figure 1. Because of the high plasticity of macrophages, the M1 and M2 phenotypes are likely to represent the extremes of a functional spectrum.9 Moreover, not all TAMs may express NOS2 or CD163, and therefore some of the macrophages may have gone undetected in our study. With improved and more specific M1 and M2 markers for use in clinical, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens, in the future we will be able to get an increased understanding of the various populations of TAMs and their role in tumor progression.

Figure 1. Distribution of M1 and M2 macrophages in colorectal carcinoma, and their potential role in tumor control.

A few studies have addressed how the immune contexture is integrated with tumor-cell molecular features, which could provide important prognostic and predictive cues. We therefore included a molecular aspect in our work, in that the M1 and M2 macrophages were analyzed separately in different molecular subgroups of CRC as defined by the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) and microsatellite instability (MSI). We found no correlation between tumor-infiltration by M1 or M2 macrophages and molecular parameters, and no major differences in the prognostic role of M1 and M2 macrophages in distinct subgroups of CRC patients as defined by their CIMP or MSI status, suggesting that the macrophage phenotype is not controlled by these molecular events in CRC.

The phenotype of TAMs reflects all events that take place in the tumor microenvironment. It is therefore tempting to speculate that the diverse roles of macrophages in different cancers might be caused by differences in the tumor microenvironment. Could it be that the intestine creates a less tumor-friendly environment than other locations? The intestine is an organ that is subjected to continuous immune stimuli, calling for several adaptations of the local immune system.10 How the macrophage response is composed is also likely to affect the contexture of other immune cells as well as other components of the tumor stroma, and hence tumor progression and patient prognosis. Further studies are required to understand how the macrophage phenotype changes in different tumor microenvironments and how this affects tumor growth and spread. This knowledge might lead to important therapeutic advances.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/23038

References

- 1.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruffell B, Affara NI, Coussens LM. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sica A, Larghi P, Mancino A, Rubino L, Porta C, Totaro MG, et al. Macrophage polarization in tumour progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heusinkveld M, van der Burg SH. Identification and manipulation of tumor associated macrophages in human cancers. J Transl Med. 2011;9:216. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erreni M, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated Macrophages (TAM) and Inflammation in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4:141–54. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forssell J, Oberg A, Henriksson ML, Stenling R, Jung A, Palmqvist R. High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1472–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegård J, Oberg A, Oldenborg PA, et al. The distribution of macrophages with a m1 or m2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber B, Saurer L, Mueller C. Intestinal macrophages: differentiation and involvement in intestinal immunopathologies. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31:171–84. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]