Abstract

Background

Phenotypic biomarkers of DNA damage repair may enhance cancer risk prediction. The γ-H2AX formed at the sites of double strands break (DSB) after ionizing radiation (IR) is a specific marker of DNA damage.

Methods

In an ongoing case-control study, the baseline and IR-induced γ-H2AX levels in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) from frequency-matched 306 untreated lung cancer patients and 306 controls were measured by a laser scanning cytometer-based immunocytochemical method. The ratio of IR-induced γ-H2AX level to the baseline was used to evaluate inter-individual variation of DSB damage response and to assess the risk of lung cancer by using unconditional multivariable logistic regression with adjustment of age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, family history of lung cancer, dust exposure and emphysema.

Results

The mean γ-H2AX ratio was significantly higher in cases than controls (1.46±0.14 vs. 1.41±0.12, P < 0.001). Dichotomized at the median in controls, high γ-H2AX ratio was significantly associated with increased risk of lung cancer (OR = 2.43, 95% CI: 1.66–3.56). There was also a significant dose-response relationship between γ-H2AX ratio and lung cancer risk in quartile analysis. Analysis of joint effects with other epidemiological risk factors revealed elevated risk with increasing number of risk factors.

Conclusion

γ-H2AX activity as shown by measuring DSB damage in IR-irradiated PBLs may be a novel phenotypic marker of lung cancer risk.

Impact

γ-H2AX assay is a robust and quantifiable image-based cytometer method that measures mutagen-induced DSB response in PBLs as a potential biomarker in lung cancer risk assessment.

Keywords: Double strands break, γ-H2AX, mutagen sensitivity, lung cancer risk

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death for both men and women in the United States. An estimated 226,000 new cases and 160,000 deaths (accounting for more than a quarter of all cancer deaths) were predicted for 2012 (1). Although it is widely recognized that cigarette smoking is the predominant risk factor for lung cancer, the fact that only about 15% of smokers will eventually develop this disease in their lifetime (2) suggests that inherited genetic susceptibility and acquired somatic changes may be involved in lung cancer etiology (3, 4).

Extensive research has been performed to identify host susceptibility to DNA damage from carcinogens, which may predispose certain individuals to increased cancer risk. One such effort is the development of mutagen sensitivity assays to quantify inter-individual variation in the extent of DNA damage by measuring chromatid breaks induced by mutagens in short-term cultures of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) (5–7). Patients with chromosome breakage syndromes such as Fanconi’s anemia, ataxia-telangiectasia and xeroderma pigmentosum have deficient DNA repair system and high rates of spontaneous chromosome breaks, and exhibit the highest mutagen sensitive phenotype(8, 9). These patients have dramatically increased risks of certain cancers (10–12). Numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated that there are wide variations of mutagen sensitivity among general population and individuals with higher mutagen sensitivity phenotype are at increased risks of various cancers, including lung cancer (5, 13–18).

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are thought to be the most deleterious type of DNA damage, which can result in genomic instability, a hallmark of many malignancies including lung cancer (19–21). It has been shown that chromatin structure is modulated in response to DNA damage (22), and one of the best characterized examples is the ATM/ATR/DNA-PK-mediated phosphorylation of serine 139 of the histone H2A variant, H2AX, on chromatin flanking DSB sites (23). The rapid formation of phosphorylated H2AX (γ-H2AX) foci occurs several minutes after DSBs were induced, bringing about ubiquitin-adduct formation, and recruiting DNA damage response factors and other chromatin-modifying components, which together are thought to promote DSB repair and amplify DSB signaling (24).

The γ-H2AX assay, which quantifies DSBs by measuring immunofluorescent foci formed after reaction of the antibodies against the phosphorylated C-terminal peptide of H2AX, has become a very accurate and sensitive assay in detecting DSBs (25). It has been demonstrated that the γ-H2AX assay (flow cytometry method) is 100 times more sensitive for detecting DSBs than the Comet assay is (26), and it is particularly useful for detecting low levels of DNA damage (27, 28). Induced by a variety of mutagens, measurements of γ-H2AX formation may be useful as a biomarker for aging and cancer, biodosimeter for drug development and radiation exposure, and phamacodynamic biomarker for cancer therapy (29–33).

In this study, we developed a new laser scanning cytometer based quantitative fluorescence method to measure the γ-H2AX level as a biomarker to assess inter-individual variability of response to DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation (IR). We hypothesized that a higher level of IR-induced DSBs as measured by γ-H2AX level in PBLs is associated with an elevated risk for lung cancer.

Materials and methods

Study population and epidemiologic data

Lung cancer patients in this study were identified from an ongoing lung cancer case-control study. Briefly, newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed lung cancer cases were recruited at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and enrolled before receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy. There were no restrictions on age, gender, ethnicity or cancer stage. The controls without a prior history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) were recruited from the Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, the largest private multispecialty physician group in the Houston metropolitan area. The potential control subjects were identified by reviewing short survey forms distributed to patients visiting the clinic. The majority of control subjects were healthy individuals coming to the clinic for an annual health check-up. All cases and controls were recruited from May 2009 to July 2011 and frequency matched by age, gender, ethnicity, and smoking status. The research protocol has been approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center and Kelsey-Seybold Clinics Institutional Review Board. All study participants signed a written informed consent. Trained staff of the MD Anderson Cancer Center administered an epidemiologic questionnaire to the participants. All the interviews were conducted face-to-face. Data were collected on demographic characteristics, tobacco use history, occupation, environmental dust exposure (34), prior medical history, and family history of cancer (i.e., cancer in first-degree relatives), etc. An individual who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime was defined as a never smoker. An individual who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime but had quit more than 12 months before the lung cancer diagnosis (for cases) or the interview (for controls) was considered a former smoker. Current smokers were those who were currently smoking or had quit less than 12 months before the diagnosis (for cases) or the interview (for controls). Ever smokers included former smokers and current smokers. Following the interview, a 40-ml blood sample was drawn for biospecimen isolation and laboratory analyses.

Whole-blood culture and γ-H2AX assay

Once blood samples arrived at the laboratory, a total of 0.4 ml whole blood of each sample was withdrawn and divided into two 0.2-ml aliquots, and each aliquot was plated in separate 30-mm dishes with 1.8 ml of RPMI 1640 (JRM Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum and 1.25% phytohemagglutinin (Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA) . The whole blood was then cultured at 37°C for 72 hr. From these two identical cultures for each study subject, one was assigned to detect baseline DSBs (untreated) and the other to detect IR-induced DSBs (treated).

Prior to the γ-H2AX assay, the cultured whole blood of the treatment set was exposed at a dose rate of 1.64 Gy/min to a total dose of 2.5 Gy of IR from a cesium-137 source (cesium irradiator Mark 1, Model 30; J.L. Shepherd and Associates, Glendale, CA) at room temperature and was returned immediately to be incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. This was based on the observation that the highest induced γ-H2AX level could be detected 1 hour after ionizing radiation exposure, in a time-course experiment using human lymphocytes isolated from peripheral blood. γ-H2AX detection was carried out for both untreated and IR-treated whole blood culture with a modification of a previously described protocol (35). Briefly, the leukocytes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Sigma) for 10 min after complete lysis of red cells, and Triton X-100 (0.12% in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was added subsequently to the leukocytes. The cells were then washed and fixed again in cold 50% methanol in PBS for 10 min. After centrifugation the leucocytes were spotted onto slides and blocked in PBS with 4% bovine serum albumin for 30 min, incubated with 1:500 diluted (1 µg/ml) mouse monoclonal γ-H2AX antibody (Biolegend) for 30 min, washed in PBS, and incubated with fluorescin isothyocyanate-conjugated horse anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. After extensive washing, the slides were mounted with Propidium Iodide counterstain (Abbott Molecular. Inc.) and covered with cover slips. All experiments were conducted at room temperature except as noted. This immunocytochemical assay was conducted simultaneously for the corresponding untreated blood sample as a baseline.

An iCys laser scanning cytometer (CompuCyte, Cambridge, MA) was used to measure the fluorescence signals. Slides were scanned automatically using a 488- nm laser, and cell counts were obtained with a 40X objective at 4-µm pixelation. Clustered cells and fragments of fluorescence were excluded during cell counting to eliminate uncountable cells and non-specific fluorescence signals. Counting continued until 5,000 dispersed and contoured cells were registered. The average readings of immunofluorescent signals per cell was obtained for baseline (un-treated) and IR-induced γ-H2AX level from each sample, and the γ-H2AX ratio, defined as the ratio of IR-induced γ-H2AX level to the baseline, was also calculated to assess lung cancer risk. All assays were performed by the same skilled laboratory technician who was blinded to the case-control status of each sample and strictly followed the experimental protocol. During the initial phase of assay development, we performed triplicate assays in some samples from non-eligible enrollments to test intra-assay reproducibility, and the results were highly consistent. The average coefficient of variation (CV) of these triplicates was 3.87% for the γ-H2AX ratio, while it was 8.28% for the baseline and 9.69% for the induced γ-H2AX level, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the Stata 10.1 statistical software package (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). The Χ2 test was used to test the difference between cases and controls for the categorical data (e.g., sex, ethnicity, smoking status, family history of cancer, etc.) and the Student’s t-test was used for analyzing the difference in age as continuous variable. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed to test the difference between cases and controls for pack-years, baseline and IR-induced γ-H2AX level, and γ-H2AX ratio. The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated as estimates of relative risk. Unconditional multivariable logistic regression was performed with adjustment to control for possible confounding by age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, family history of lung cancer, dust exposure and emphysema where appropriate. To assess for the presence of a trend in lung cancer risk according to degree of DNA damage, we analyzed the data of baseline, IR-induced γ-H2AX level and γ-H2AX ratio, using the dichotomization and quartiles of the controls as cut-off points. All P values were two-sided, and associations were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics and γ-H2AX level in cases and controls

The data of demographic characteristics and γ-H2AX level of cases and controls were summarized in Table 1. The study included 306 lung cancer cases and 306 healthy control subjects. As a result of frequency matching, there was no statistically significant difference between cases and controls regarding to age and gender. The majority of subjects, 91.2% of cases and 84.6% of controls, were Caucasians. There were significantly more current smokers among cases than controls (35.3% vs. 22.6%, P<0.001) and significantly more ever-smokers among cases than controls (84.6% vs. 58.2%, P<0.001). In smokers, the self-reported median pack years were significantly higher in cases than in controls (46.0 for cases and 26.0 for controls, P<0.001). There were also significant case-control differences in a panel of epidemiological factors, including family history of lung cancer (in first degree relatives), prior history of dust exposure, and prior history of emphysema (all P<0.01). There were three measures of γ-H2AX level: baseline, IR-induced, and the ratio of these two. A higher IR-induced γ-H2AX level (1195.5 vs. 1081.4, P = 0.003) and γ-H2AX ratio (1.46 vs. 1.41, P<0.001) were observed in cases as compared to controls. However, there was no significant difference in the baseline γ-H2AX level between cases and controls (818.2 vs. 770.5, P = 0.094) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of selected host characteristics by case-control status

| Variables | Cases(N=306) | Controls(N=306) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean(SD) | 63.9(10.2) | 63.5(10.5) | 0.635a |

| Sex, n(%) | |||

| Male | 159(52.0) | 155(50.7) | |

| Female | 147(48.0) | 151(49.3) | 0.746b |

| Ethnicity, n(%) | |||

| Caucasians | 279(91.2) | 259(84.6) | |

| African Americans | 22(7.2) | 33(10.8) | |

| Hispanics | 5(1.6) | 14(4.6) | 0.027b |

| Smoking status, n(%) | |||

| Never | 47(15.4) | 128(41.8) | |

| Former | 151(49.3) | 109(35.6) | |

| Current | 108(35.3) | 69(22.6) | <0.001b |

| Ever | 259(84.6) | 178(58.2) | <0.001b |

| Pack-years, mean (SD) | 46.0(32.5) | 26.0(25.4) | <0.001c |

| Family history of all cancers, n(%) | |||

| Yes | 159(53.5) | 136(46.3) | |

| No | 138(46.5) | 158(53.7) | 0.077b |

| Family history of lung cancer, n(%) | |||

| Yes | 113(37.1) | 80(26.6) | |

| No | 192(62.9) | 221(73.4) | 0.006b |

| Dust exposure, n(%) | |||

| Yes | 113(36.9) | 39(12.8) | |

| No | 193(63.1) | 265(87.2) | <0.001b |

| Emphysema, n(%) | |||

| Yes | 55(18.1) | 8 (2.6) | |

| No | 249(81.9) | 296(97.4) | <0.001b |

| γ-H2AX level, mean (SD) | |||

| Baselined | 818.2(275.0) | 770.5(226.7) | 0.094c |

| IR-inducedd | 1195.5(425.7) | 1081.4(320.1) | 0.003c |

| γ-H2AX ratioe | 1.46(0.14) | 1.41(0.12) | 6.65E-08c |

| Histology, n(%) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 191(62.4) | ||

| Squamous | 60(19.6) | ||

| Other non-small cell | 33(10.8) | ||

| Small cell | 22(7.2) |

P value was derived from Student’s t-test. All P values are two-sided.

P values were derived from the Pearson Χ2 test.

P values were derived from the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Baseline and induced γ-H2AX level were the original readings of the fluorescence signals by cytometer.

γ-H2AX ratio was the ratio of the IR-induced γ-H2AX level to the baseline level of the same sample.

Modification of γ-H2AX ratio by epidemiological factors

Older subjects (age ≥ 64) exhibited significantly lower γ-H2AX ratio than younger people (age < 64) in both cases and controls (P = 0.013 and 0.034, respectively). Smoking status, pack-years of smoking for ever smokers, family history of all cancer, family history of lung cancer, history of dust exposure and history of emphysema did not modify γ-H2AX ratio, neither in cases nor in controls. A statistically significantly higher γ-H2AX ratio was observed in cases than in controls for all the stratified subgroups (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference of γ-H2AX ratio among different histological subtypes.

Table 2.

γ-H2AX ratio by host characteristics in cases and controls

| Cases |

Controls |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean(SD) | P a | N | Mean(SD) | P a | P b | |

| Overall | 306 | 1.46(0.14) | 306 | 1.41(0.12) | <0.001 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 159 | 1.47(0.15) | 155 | 1.42(0.13) | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 147 | 1.45(0.14) | 0.620 | 151 | 1.40(0.12) | 0.237 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||||

| <64c | 141 | 1.48(0.15) | 159 | 1.43(0.14) | <0.001 | ||

| ≥64 | 165 | 1.44(0.13) | 0.013 | 147 | 1.39(0.10) | 0.034 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | 47 | 1.46(0.12) | Ref. | 128 | 1.41(0.13) | Ref. | 0.002 |

| Former | 151 | 1.45(0.13) | 109 | 1.41(0.12) | 0.003 | ||

| Current | 108 | 1.48(0.16) | 0.909d | 69 | 1.40(0.10) | 0.742d | 0.001 |

| Ever | 259 | 1.46(0.15) | 0.352 | 178 | 1.41(0.11) | 0.751 | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | |||||||

| <33e | 94 | 1.46(0.15) | 113 | 1.42(0.11) | 0.010 | ||

| ≥33 | 162 | 1.46(0.14) | 0.811 | 57 | 1.39(0.12) | 0.336 | <0.001 |

| Family history of all cancers | |||||||

| Yes | 159 | 1.46(0.14) | 136 | 1.41(0.13) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 138 | 1.47(0.15) | 0.673 | 158 | 1.41(0.11) | 0.711 | <0.001 |

| Family history of lung cancer | |||||||

| Yes | 113 | 1.46(0.15) | 80 | 1.41(0.14) | 0.009 | ||

| No | 192 | 1.46(0.14) | 0.806 | 221 | 1.41(0.11) | 0.883 | <0.001 |

| Dust exposure | |||||||

| Yes | 113 | 1.45(0.14) | 39 | 1.39(0.13) | 0.021 | ||

| No | 193 | 1.46(0.14) | 0.156 | 265 | 1.41(0.12) | 0.483 | <0.001 |

| Emphysema | |||||||

| Yes | 55 | 1.48(0.15) | 8 | 1.36(0.07) | 0.021 | ||

| No | 249 | 1.46(0.14) | 0.472 | 296 | 1.41(0.12) | 0.366 | <0.001 |

P values for the differences between subgroups by the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

P values for the difference between cases and controls.

Median age of the controls.

P values for trend derived from the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Median of pack-years among overall ever smokers.

The association and dose-response relationship between γ-H2AX ratio and lung cancer risk

When γ-H2AX ratio were dichotomized by the median value in the controls, a statistically significant increased risk of lung cancer (OR = 2.43; 95% CI = 1.66–3.56; P<0.001) was observed in those with higher γ-H2AX ratio. However, no significant increased risk could be observed when similar analysis was performed based on baseline and IR-induced γ-H2AX level (Table 3). When risk was estimated for subgroups stratified by sex, age, smoking status, pack years, family history of all cancer, family history of lung cancer, history of dust exposure, and history of emphysema, similar increased risk was observed for all the strata. The OR varied from 1.74–3.41, with a higher relative risk observed for never smokers, compared to the same risk estimated for ever smokers (OR = 3.41 and 2.23, respectively). There was a significant trend of increased lung cancer risk with increasing γ-H2AX ratio in quartile analysis. Compared to individuals in the lowest quartile of γ-H2AX ratio, those in the second, the third and the highest quartile of γ-H2AX ratio exhibited a 1.08-fold (95% CI, 0.60–1.94), 1.85-fold (95% CI, 1.08–3.20) and 3.32-fold (95% CI, 1.94–5.70) increased risk, respectively (P for trend <0.001) after adjustment (as above). No trend was observed when relative risk was estimated for baseline and IR-induced γ-H2AX level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relative risk estimates of lung cancer for baseline, IR-induced γ-H2AX level and γ-H2AX ratio by dichotomized and quartile analysis

| γ-H2AX level | Cases, N(%) | Controls, N(%) | Adjusted OR a (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselineb | ||||

| Median | ||||

| <755 | 141(46.1) | 153(50.0) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| ≥755 | 165(53.9) | 153(50.0) | 1.18(0.82–1.69) | 0.374 |

| Quartile | ||||

| <596 | 63(20.5) | 78(25.5) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| 596–755 | 78(25.5) | 75(24.5) | 1.23(0.73–2.05) | 0.441 |

| 755–937 | 77(25.2) | 78(25.5) | 1.15(0.76–1.75) | 0.421 |

| ≥937 | 88(28.8) | 75(24.5) | 1.39(0.83–2.33) | 0.213 |

| P for trend | 0.237 | |||

| IR-inducedc | ||||

| Median | ||||

| <1053 | 131(42.8) | 153(50.0) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| ≥1053 | 175(57.2) | 153(50.0) | 1.35(0.94–1.94) | 0.107 |

| Quartile | ||||

| <846 | 63(20.6) | 77(25.2) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| 846–1053 | 68(22.2) | 76(24.8) | 0.95(0.56–1.61) | 0.854 |

| 1053–1298 | 72(23.5) | 77(25.2) | 1.12(0.66–1.89) | 0.685 |

| ≥1298 | 103(33.7) | 76(24.8) | 1.52(0.91–2.53) | 0.110 |

| P for trend | 0.075 | |||

| γ-H2AX ratiod | ||||

| Median | ||||

| <1.40 | 93(30.4) | 153(50.0) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| ≥1.40 | 213(69.6) | 153(50.0) | 2.43(1.66–3.56) | <0.001 |

| Quartile | ||||

| <1.34 | 47(15.4) | 77(25.2) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| 1.34–1.40 | 46(15.0) | 76(24.8) | 1.08(0.60–1.94) | 0.809 |

| 1.40–1.46 | 87(28.4) | 77(25.2) | 1.85(1.08–3.20) | 0.026 |

| ≥1.46 | 126(41.2) | 76(24.8) | 3.32(1.94–5.70) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 |

Adjusted by age, sex, smoking status and ethnicity, family history of lung cancer, history of dust exposure and history of emphysema.

Categorized by median and quartiles of baseline γ-H2AX level in the controls.

Categorized by median and quartiles of γ-radiation induced H2AX level in the controls.

Categorized by median and quartiles of γ-H2AX ratio in the controls.

Joint effects of mutagen sensitivity and other risk factors of lung cancer

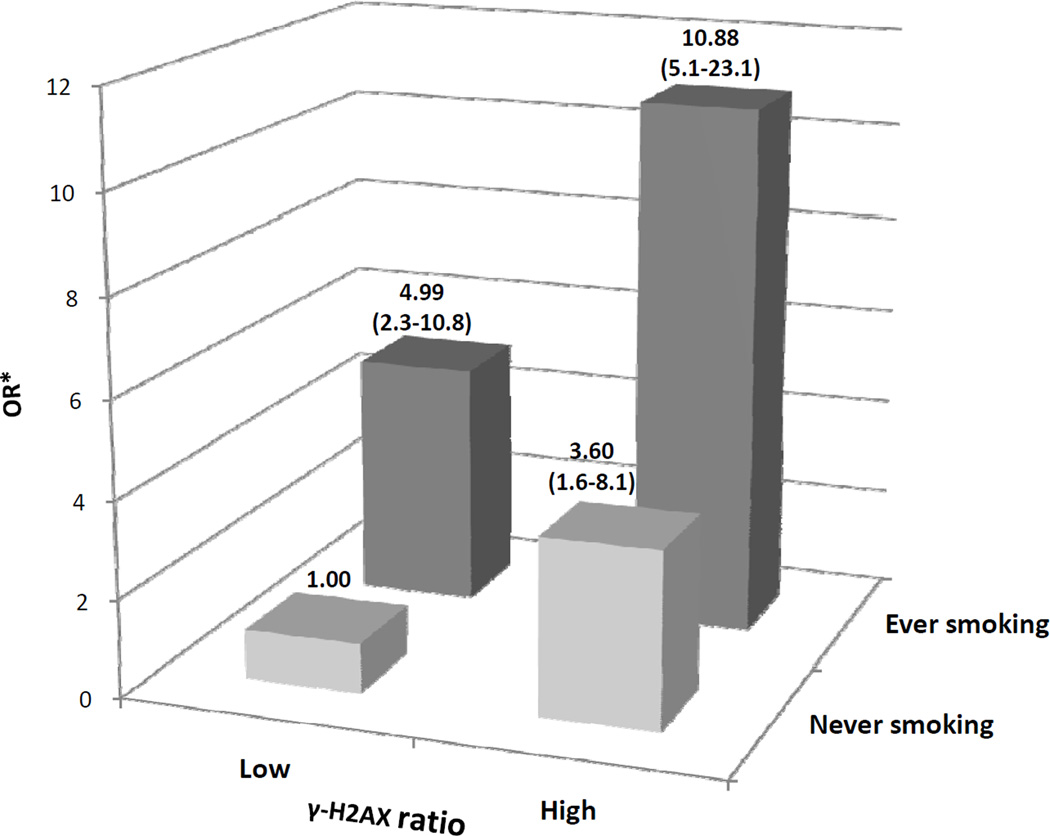

We further assessed the multiplicative joint effects of γ-H2AX ratio and smoking status on the risk for lung cancer (Figure 1). Cases and controls were categorized into 4 groups by γ-H2AX ratio (low or high as dichotomized by the median value in controls) as well as by smoking status (never or ever smoking). Subjects in the absence of both of these two risk factors (i.e. “low γ-H2AX ratio & never smoking”) were used as the reference group. Compared with this group “high ratio & never smoking”, “low ratio & ever smoking”, and “high ratio & ever smoking” groups showed a gradual increase of lung cancer risk with ORs of 3.60, 4.99 and 10.88, respectively. No interaction between smoking status and γ-H2AX ratio was detected (P =0.285). There were also significant joint effects of the γ-H2AX ratio with other epidemiological risk factors including family history of cancer, exposure of dust and history of emphysema on the risk estimated of lung cancer (data note shown).

Figure 1.

Joint effects of γ-H2AX ratio with smoking status on risk of lung cancer. “Low” referred to subjects with γ-H2AX ratio < median (1.40) of the controls, and “High” referred to subjects with γ-H2AX ratio ≥ median (1.40) of the controls. *Adjusted by age, sex, ethnicity, history of lung cancer, history of dust exposure, and history of emphysema. Numbers in parentheses are the 95% confidence intervals.

Finally, we assessed lung cancer risk in the context of the multiple significant risk factors identified in multivariate analyses, which were also reported in our previous lung cancer risk prediction model(34). These risk factors included DSB response (γ-H2AX ratio), history of emphysema, family history of lung cancer, exposure to dust, and history of emphysema. Subjects with 4 or 5 of these risk factors exhibited a much higher risk of developing lung cancer, compared to those without any of these risk factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Joint effects of γ-H2AX ratio with selected epidemiological risk factors in lung cancer risk

| No. of risk factors | Cases, N(%) | Controls, N(%) | Adjusted OR(95%CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6(2.0) | 39(12.9) | 1.00(ref.) | |

| 1 | 41(13.5) | 120(39.9) | 1.87(0.71–4.91) | 0.207 |

| 2 | 109(36.0) | 99(32.9) | 5.48(2.05–14.63) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 104(34.3) | 38(12.6) | 12.87(4.53–36.55) | <0.001 |

| ≥4 | 43(14.2) | 5(1.7) | 40.53(10.40–158.87) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 |

Adjusted by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Risk factors included high γ-H2AX ratio, ever smoking, positive family history of lung cancer, positive dust exposure, and positive history of emphysema.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a laser scanning cytometer-based immunocytochemical method to quantify DSB damage as measure by γ-H2AX level in cultured PBLs at baseline and after IR induction. We showed that a higher ratio of IR-induced γ-H2AX level to the baseline γ-H2AX level is associated with an increased risk for lung cancer and that there was a significant dose-response. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study applying the γ-H2AX assay in human population studies for lung cancer risk assessment.

DSBs can be detected by many methods, such as neutral elution, pulsed field electrophoresis (2–dimensional gel electrophoresis), alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis (Comet assay) (36–39), and γ-H2AX assay. There have been efforts to apply new objective image-based techniques, such as the Comet assay, to increase the throughput of counting chromosome and DNA damage upon mutagen challenge that may be more suitable for population based studies (36, 37, 40). However, none has been widely adopted in epidemiological studies. The ease and economy of our current assay may provide a convenient means and consistent biomarker for cancer risk assessment.

The γ-H2AX ratio was applied to evaluate inter-individual variation of DSB damage response and to assess lung cancer risk. It is important to note that endogenous γH2AX foci, usually in small numbers, may be present in cells even in the absence of DNA damage from exogenous source because DSBs can occur during many common cellular processes, including DNA replication, cellular senescence, and exposure to endogenous reactive oxygen species (41). The slightly higher γ-H2AX level at baseline in the cases (Table 1) suggests perhaps more diminished DNA repair capacity compared to the controls. However, it did not show the effectiveness in assessing lung cancer risk. Moreover, due to the sensitivity of the assay in detecting DSBs, minor variability of conditions in acquisition and storage of blood sample, such as different interval time between blood drawing and experiment, could result in variation for the baseline signals and confound the subsequent measurement of IR-induced γ-H2AX level. The use of induced γ-H2AX ratio should lessen confounding on baseline activity. Our results suggest that γ-H2AX ratio is robust for assessing lung cancer risk and reveals a significant dose-response relationship with lung cancer susceptibility (Table 3).

It is also noteworthy that in most DNA repair assays used for assessing cancer risk there is apparent overlap between DNA damage and repair (42). Similarly, by detecting unrepaired DSBs, the γ-H2AX assay could be used to speculate about susceptibility to DSB, variation in repair capacity, or the global effects of both, depending on when the detection occurs. The kinetics of γ-H2AX in irradiated PBLs were well described in that it reached a peak and maintained it from 30 min to 2 hr post irradiation (35, 43–45), an interval which covered the time point of detecting the IR-induced γ-H2AX in the current study. Therefore although manifesting the summary effect of DSB induction and DNA repair in early phase of the kinetics, the ratio should most likely reflect the degree of inducibility of DSB formation in PBLs by mutagen challenge, which was presumed to be associated with cancer susceptibility.

It is widely recognized that both genetic and environmental factors play important roles in the etiology of lung cancer (13, 34, 46–48). Because genomic instability is a fundamental feature of cancer (49), individuals with higher genomic instability might be at a greater risk for developing cancer(14). Mutagen sensitivity, which measures indirectly DNA repair capacity by quantifying DNA damage induced by mutagen in short-term cultures of PBLs, has been widely evaluated as a phenotypic susceptibility marker in case-control studies (reviewed in ref. 7 and 42) as well as in a few prospective studies (50, 51).The original mutagen sensitivity assay manually counted chromatid breaks with a microscope by a skilled technician, which was time-consuming, laborious and subjective (5, 46). The IR-induced DSBs as measured by the objective and high-throughput γ-H2AX assay as developed in this study is a significant improvement of traditional mutagen sensitivity assay. In response to environmental exposures, individuals with high genetic susceptibility to DNA damage generate more DNA damage than do those with low susceptibility, even with similar exposure. For individuals with heavy environmental exposure, such as heavy cigarette smoking, genetic risk factors tend to exert weaker effects because the strong impact of carcinogen exposure could overpower any genetic predisposition. Previous epidemiologic investigation has shown an increased incidence of non-smoking-related lung cancer (52). The γ-H2AX assay could provide important information regarding genetic predisposition factors for lung cancer in non-smokers. We found that, among never smokers, those with a higher γ-H2AX ratio exhibited a 3.4-fold increased risk for lung cancer compared to those with a lower ratio. The risk estimated in never smokers was higher than the same risk estimated in ever smokers (OR = 2.23), suggesting that genetic susceptibility to DNA damage plays a more prominent role in the development of lung cancer in never smokers than in ever smokers.

Numerous studies suggested the combination of mutagen sensitivity with other risk factors increase predictive power (6, 15, 53). We analyzed the joint effect between tobacco smoking and γ-H2AX ratio and found a more than 10-fold increased risk of lung cancer for individuals with high γ-H2AX ratio plus ever smoking status (Figure 1). When we assessed the risk in the context of multiple epidemiological risk factors, a significant dose-dependent increase in risk was observed in subjects with higher number of risk factors, which indicated the cumulative effects and joint interaction of genetic and environmental risk factors on lung cancer development.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, although in the current study cancer treatment was not a confounder of DNA damage response between cases and controls, using post-diagnostic samples is not ideal for assessing the predictive value of phenotypic assays because their outcome might be affected by disease status or associated factors such as treatment. This “reverse causation” issue is an inherent limitation of retrospective case-control studies; nevertheless several previous studies have shown that response to mutagen challenges has high heritability (54–56), suggesting strong genetic component. Future studies employing a prospective design are warranted to confirm the association between DNA damage, as assessed by γ-H2AX assay, and lung cancer risk. Secondly, there might be some differences in the interval between blood collection and the cell-based experiment among the different batches of samples collected, which could influence baseline activity. These changes could not be predicted a priori or completely avoided. Nevertheless, we sought to minimize the interval time between blood draw and whole blood culture. Thirdly, we recognize that the base population of cases cannot be clearly defined, however, when controls at Kelsey-Seybold clinics are diagnosed with cancer, they are often referred to MD Anderson for treatment, suggesting that controls are largely derived from the population from which the majority of cases arise. Furthermore, the hypothesis of our study is mostly due to inherited variation in mutagen sensitivity and cancer risk with a minor environmental component. Although differences in catchment areas may impact both genetic and environmental factors, these biases are likely to be minimal as major environmental factors thought to influence the measured trait were controlled in the analysis, and there are no major ethnic differences between the case and control samples, although minor differences in ethnic makeup within major categories cannot be excluded. Although differences in catchment areas may impact both genetic and environmental factors, these biases are likely to be minimal as the major environmental factors thought to influence the measured trait were controlled in the analysis. There are no major ethnic differences between the case and control samples, although minor differences in ethnic makeup within major categories cannot be excluded. Adjustment for income did not result in appreciable changes in ORs suggesting that confounding from socioeconomic status is minimal in this study. Finally, we only evaluated IR-induced DSBs level at a single time point (1 hr) post-irradiation. Thus we are unable to evaluate DSB repair capacity during an entire time course. Bourton et al.(44) recently investigated the role of detecting γ-H2AX in the irradiated PBLs to assess the radiation sensitivity of normal tissue in cancer patients. They found a significantly higher induction and persistence of γ-H2AX signal over 24 hr period in PBLs from patients with excessive normal tissue toxicity after radiation therapy, compared to those without toxicity, indicating persistent γ-H2AX signal and reduced DNA DSB repair correlated with cancer patients with radiation toxicity. Thus, determination of γ-H2AX levels in PBLs over different time points after IR treatment may be warranted to further characterize the host’s capacity to repair DSBs.

In conclusion, we have established a robust and relatively high-throughput laser scanning cytometer based quantitative assay to measure DSB damage in PBLs. Our data showed that IR-irradiated PBLs from lung cancer patients exhibited higher level of induced DSBs compared to those from control subjects. This is the first epidemiologic study using the γ-H2AX assay to assess mutagen sensitivity and lung cancer risk. The γ-H2AX assay will require further confirmation in additional cancer and non-cancer populations and study in co-morbid conditions before it can be applied to clinical models of cancer risk assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support

This research was supported in part by National Cancer Institute (R01 CA111646 P50 CA070907, and R01 CA055769). Additional funding was provided by MD Anderson Research Trust.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Reference

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villeneuve PJ, Mao Y. Lifetime probability of developing lung cancer, by smoking status, Canada. Can J Public Health. 1994;85:385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risch A, Plass C. Lung cancer epigenetics and genetics. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Sheu CC, Ye Y, de Andrade M, Wang L, Chang SC, et al. Genetic variants and risk of lung cancer in never smokers: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:321–330. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu TC, Johnston DA, Cherry LM, Ramkissoon D, Schantz SP, Jessup JM, et al. Sensitivity to genotoxic effects of bleomycin in humans: possible relationship to environmental carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:403–409. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitz MR, Fueger JJ, Beddingfield NA, Annegers JF, Hsu TC, Newell GR, et al. Chromosome sensitivity to bleomycin-induced mutagenesis, an independent risk factor for upper aerodigestive tract cancers. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4626–4628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X, Gu J, Spitz MR. Mutagen sensitivity: a genetic predisposition factor for cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3493–3495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishida R, Buchwald M. Susceptibility of Fanconi's anemia lymphoblasts to DNA-cross-linking and alkylating agents. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4000–4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Futaki M, Liu JM. Chromosomal breakage syndromes and the BRCA1 genome surveillance complex. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:560–565. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kupfer GM, Naf D, D'Andrea AD. Molecular biology of Fanconi anemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1997;11:1045–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeggo PA, Carr AM, Lehmann AR. Splitting the ATM: distinct repair and checkpoint defects in ataxia-telangiectasia. Trends Genet. 1998;14:312–316. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berneburg M, Lehmann AR. Xeroderma pigmentosum and related disorders: defects in DNA repair and transcription. Adv Genet. 2001;43:71–102. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(01)43004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu TC, Spitz MR, Schantz SP. Mutagen sensitivity: a biological marker of cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1991;1:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu X, Lin J, Etzel CJ, Dong Q, Gorlova OY, Zhang Q, et al. Interplay between mutagen sensitivity and epidemiological factors in modulating lung cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2687–2695. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cloos J, Spitz MR, Schantz SP, Hsu TC, Zhang ZF, Tobi H, et al. Genetic susceptibility to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:530–535. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.8.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strom SS, Wu S, Sigurdson AJ, Hsu TC, Fueger JJ, Lopez J, et al. Lung cancer, smoking patterns, and mutagen sensitivity in Mexican-Americans. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1995:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng YL, Loffredo CA, Yu Z, Jones RT, Krasna MJ, Alberg AJ, et al. Bleomycin-induced chromosome breaks as a risk marker for lung cancer: a case-control study with population and hospital controls. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:269–274. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu J, Horikawa Y, Chen M, Dinney CP, Wu X. Benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide-induced chromosome 9p21 aberrations are associated with increased risk of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2445–2450. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda A, Takahashi T. Chromosome instability in human lung cancers: possible underlying mechanisms and potential consequences in the pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:6884–6897. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills KD, Ferguson DO, Alt FW. The role of DNA breaks in genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:77–95. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson C, Jasin M. Frequent chromosomal translocations induced by DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2000;405:697–700. doi: 10.1038/35015097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misteli T, Soutoglou E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:243–254. doi: 10.1038/nrm2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redon C, Pilch D, Rogakou E, Sedelnikova O, Newrock K, Bonner W. Histone H2A variants H2AX and H2AZ. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:162–169. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huen MS, Chen J. The DNA damage response pathways: at the crossroad of protein modifications. Cell Res. 2008;18:8–16. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothkamm K, Lobrich M. Evidence for a lack of DNA double-strand break repair in human cells exposed to very low x-ray doses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5057–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830918100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ismail IH, Wadhra TI, Hammarsten O. An optimized method for detecting gamma-H2AX in blood cells reveals a significant interindividual variation in the gamma-H2AX response among humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banath JP, Macphail SH, Olive PL. Radiation sensitivity, H2AX phosphorylation, and kinetics of repair of DNA strand breaks in irradiated cervical cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7144–7149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sedelnikova OA, Pilch DR, Redon C, Bonner WM. Histone H2AX in DNA damage and repair. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:233–235. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobrich M, Rief N, Kuhne M, Heckmann M, Fleckenstein J, Rube C, et al. In vivo formation and repair of DNA double-strand breaks after computed tomography examinations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8984–8989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501895102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sedelnikova OA, Horikawa I, Redon C, Nakamura A, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, et al. Delayed kinetics of DNA double-strand break processing in normal and pathological aging. Aging Cell. 2008;7:89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Zhang YW, Ji JJ, Bonner WM, Kinders RJ, et al. Histone gammaH2AX and poly(ADP-ribose) as clinical pharmacodynamic biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4532–4542. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinders RJ, Hollingshead M, Lawrence S, Ji J, Tabb B, Bonner WM, et al. Development of a validated immunofluorescence assay for gammaH2AX as a pharmacodynamic marker of topoisomerase I inhibitor activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5447–5457. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S, et al. GammaH2AX and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitz MR, Hong WK, Amos CI, Wu X, Schabath MB, Dong Q, et al. A risk model for prediction of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:715–726. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrievski A, Wilkins RC. The response of gamma-H2AX in human lymphocytes and lymphocytes subsets measured in whole blood cultures. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85:369–376. doi: 10.1080/09553000902781147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kassie F, Parzefall W, Knasmuller S. Single cell gel electrophoresis assay: a new technique for human biomonitoring studies. Mutat Res. 2000;463:13–31. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colleu-Durel S, Guitton N, Nourgalieva K, Legue F, Leveque J, Danic B, et al. Alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay): a simple technique to show genomic instability in sporadic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Delgado DA, Deen DF. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to investigate factors influencing the measurement of DNA double-strand breaks in human brain tumour specimens. Int J Radiat Biol. 1995;67:153–160. doi: 10.1080/09553009514550191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prise KM, Ahnstrom G, Belli M, Carlsson J, Frankenberg D, Kiefer J, et al. A review of dsb induction data for varying quality radiations. Int J Radiat Biol. 1998;74:173–184. doi: 10.1080/095530098141564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu X, Roth JA, Zhao H, Luo S, Zheng YL, Chiang S, et al. Cell cycle checkpoints, DNA damage/repair, and lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2005;65:349–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S, et al. GammaH2AX and cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2008;8:957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berwick M, Vineis P. Markers of DNA repair and susceptibility to cancer in humans: an epidemiologic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:874–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.11.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamasaki K, Imai K, Nakachi K, Takahashi N, Kodama Y, Kusunoki Y. Short-term culture and gammaH2AX flow cytometry determine differences in individual radiosensitivity in human peripheral T lymphocytes. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2007;48:38–47. doi: 10.1002/em.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bourton EC, Plowman PN, Smith D, Arlett CF, Parris CN. Prolonged expression of the gamma-H2AX DNA repair biomarker correlates with excess acute and chronic toxicity from radiotherapy treatment. Int J Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.25953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacPhail SH, Banath JP, Yu TY, Chu EH, Lambur H, Olive PL. Expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX in cultured cell lines following exposure to X-rays. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:351–358. doi: 10.1080/0955300032000093128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Delclos GL, Annegers JF, Bondy ML, Honn SE, Henry B, et al. A case-control study of wood dust exposure, mutagen sensitivity, and lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spitz MR, Hsu TC, Wu X, Fueger JJ, Amos CI, Roth JA. Mutagen sensitivity as a biological marker of lung cancer risk in African Americans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brennan P, Hainaut P, Boffetta P. Genetics of lung-cancer susceptibility. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:399–408. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chao DL, Maley CC, Wu X, Farrow DC, Galipeau PC, Sanchez CA, et al. Mutagen sensitivity and neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a prospective analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1935–1940. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sigurdson AJ, Jones IM, Wei Q, Wu X, Spitz MR, Stram DA, et al. Prospective analysis of DNA damage and repair markers of lung cancer risk from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:69–73. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boffetta P, Jarvholm B, Brennan P, Nyren O. Incidence of lung cancer in a large cohort of non-smoking men from Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:591–593. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu X, Yu H, Amos CI, Hong WK, Spitz MR. Joint effect of insulin-like growth factors and mutagen sensitivity in lung cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:737–743. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cloos J, Nieuwenhuis EJ, Boomsma DI, Kuik DJ, van der Sterre ML, Arwert F, et al. Inherited susceptibility to bleomycin-induced chromatid breaks in cultured peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1125–1130. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts SA, Spreadborough AR, Bulman B, Barber JB, Evans DG, Scott D. Heritability of cellular radiosensitivity: a marker of low-penetrance predisposition genes in breast cancer? Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:784–794. doi: 10.1086/302544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu X, Spitz MR, Amos CI, Lin J, Shao L, Gu J, et al. Mutagen sensitivity has high heritability: evidence from a twin study. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5993–5996. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.