Abstract

African Americans are disproportionately infected and affected by HIV/AIDS. Although faith-based institutions play critical leadership roles in the African American community, the faith-based response to HIV/AIDS has historically been lacking. We explore recent successful strategies of a citywide HIV/AIDS awareness and testing campaign developed in partnership with 40 African American faith-based institutions in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a city with some of the United State’s highest HIV infection rates. Drawing on important lessons from the campaign and subsequent efforts to sustain the campaign’s momentum with a citywide HIV testing, treatment and awareness program, we provide a roadmap for engaging African American faith communities in HIV prevention that include partnering with faith leaders; engaging the media to raise awareness, destigmatising HIV/AIDS and encouraging HIV testing; and conducting educational and HIV testing events at houses of worship. African American faith based institutions have a critical role to play in raising awareness about the HIV/AIDS epidemic and for reducing racial disparities in HIV infection.

Keywords: African Americans, HIV/AIDS, health disparities, faith community, clergy, pastors

Introduction

Approximately 1.1 million Americans are living with HIV/AIDS. Although African Americans comprise only 13% of the population, they account for nearly half of new HIV infections annually (Hall et al. 2008). African Americans have seven times the rates of HIV infection as whites. Although African Americans are tested for HIV at higher rates than individuals of other races (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2002, Ebrahim et al. 2004, Kaiser Family Foundation 2006, Liddicoat et al. 2006) are more likely to get tested late in the course of infection (CDC 2003) and have higher rates of AIDS-related mortality than individuals of other races (CDC 2008).

HIV risk-taking behaviours that have historically been used to explain trends in HIV infection such as drug use, condom use and number of lifetime sexual partners do not account for these observed disparities in HIV infection (Hallfors et al. 2007). These findings suggest that social determinants of health, including African Americans’ sexual networks, geography, and stigma that inhibits more widespread testing are important drivers of racial disparities in HIV infection in the United States (US) (Hallfors et al. 2007, Aral et al. 2008, CDC 2011). Moreover, African Americans are also nearly twice as likely to be uninsured, constraining access to HIV testing. Despite these trends and scientific evidence that finds that structural and social factors contribute to these health disparities, a disproportionate share of federal HIV prevention funds are spent on behavioural interventions rather than interventions to address the social determinants of HIV infection among African Americans.

African American faith-based institutions and black churches in particular, have historically played important political, leadership and social support roles in the African American community (Lincoln and Mamiyam 1990). Nationwide surveys find African Americans are the most religiously committed racial group, attend worship services more frequently than other racial groups, and are more likely to support religious engagement on important social and political issues (Pew 2008). Religious involvement has been associated with better mental and physical health in many studies (Ellison and Levin 1998, Koenig et al. 2001, Levin 2001, Levin et al. 2005). Dozens of successful health prevention and promotion interventions have been developed and implemented in partnership with African American faith institutions, including weight loss (Davis et al.2011, Yeary et al. 2011), diabetes control (Boltri et al. year), cardiovascular health (DeHaven et al. 2011), and nutrition programs (Buta et al. 2011).

Much of the literature on HIV/AIDS and religious institutions has focused on how religion impacts individual behaviours; recent research highlights the critical need for new frameworks that explore the critical role of religion in social fabric and therefore in community health and well-being, particularly for HIV/AIDS (Chin et al. 2011, Munoz-Laboy et al. 2011, Wilson et al. 2011). In spite of the importance of spirituality for African Americans living with HIV/AIDS (Foster and Gaskins 2009), engaging African American faith-based institutions in HIV prevention has been challenging, often due to stigma, denial, homophobia, reluctance to discuss human sexuality in faith-based contexts, limited resources, and insufficient knowledge about local epidemics (Cunningham et al. 2009, Williams et al. 2011). Nevertheless, an emerging body of research highlights willingness of African American clergy to engage in HIV prevention (Coleman et al. YEAR, Foster et al. YEAR, NAACP YEAR, CDC 2002, Nunn et al. 2011a, Wilson et al. 2011, Nunn et al. 2012a).

National HIV/AIDS strategy and reducing racial disparities in HIV infection

Although the US has had a robust policy response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, until recently, there was not a central, coordinated federal approach to address the epidemic. In 2010, the Obama Administration adopted a National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) to coordinate disparate federal agencies to achieve three primary goals: reducing HIV incidence, increasing access to care and optimising health outcomes, and reducing HIV-related health disparities (Office of National AIDS Policy 2010).

New research shows that commencing antiretroviral therapy can enhance HIV prevention because individuals receiving therapy who become virologically suppressed are less likely to transmit the HIV virus to their partners (Cohen et al. 2011). Achieving the NHAS goal of reducing racial disparities in HIV infection will therefore require diagnosing more individuals, particularly African Americans, early in the course of their infection and effectively linking them to treatment, care and prevention services. Because many of the factors that place African Americans at risk for HIV/AIDS are structural or social in nature, novel approaches to HIV prevention are needed, including programmes to address stigma, encourage testing, and cultivate community leaders in responding to the epidemic.

Engaging African American faith-based institutions in HIV prevention should be a critical component of addressing President Obama’s goals of reducing racial disparities in HIV infection and improving linkage to HIV/AIDS care services for African Americans. This article explored recent successful strategies of a citywide HIV/AIDS awareness and testing campaign that included 40 faith-based institutions in Philadelphia and outlines a novel approach for engaging African American faith institutions in HIV prevention.

Philadelphia’s citywide faith-based HIV/AIDS prevention campaign

Racial disparities in HIV/AIDS infection in Philadelphia

Racial disparities in HIV infection are particularly pronounced in Philadelphia, where African Americans comprise 44% of the population but account for 69% of new HIV infections (Schwartz et al. 2010). African Americans presenting for HIV testing in public clinics in Philadelphia generally perceive themselves at low risk for contracting HIV despite high HIV prevalence and reporting high-risk behaviours (Nunn et al. 2011b, 2012c). They also report experiencing heavy stigma associated with HIV/AIDS (Nunn et al. 2012a, 2012c). These challenges underscore the need for novel approaches to HIV prevention in Philadelphia and other urban epicentres to raise HIV/AIDS awareness and encourage HIV testing.

Philadelphia has a rich religious history and is home to many of the first African American churches in the country. In June 2010 we initiated a community-based research project sponsored by Brown University and Philadelphia Mayor Nutter’s Office of Faith-Based Initiatives. We commenced with focus groups among African American Pastors, Imams, and other clergy about how to enhance HIV prevention among faith-based institutions in Philadelphia (Nunn et al. 2012b). Our focus groups found that African American faith leaders were willing and poised to engage in HIV prevention, and culminated in a call to action and a citywide HIV testing, education and media campaign in partnership with 40 faith-based institutions in Philadelphia in November 2010 (Nunn et al. 2012b).

Programme components: media, education and testing, and preaching

The campaign’s 3 primary components included 1) a citywide media campaign to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS in the African American community and the importance of engaging faith-based leaders; 2) HIV testing and educational events at mosques and churches; and 3) sermons about HIV/AIDS. Collaborators included Brown University researchers, Philadelphia Mayor’s Office of Faith-Based Initiatives, local churches and mosques, and Greater than AIDS (GTA), a national initiative directed by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Black AIDS Institute. Through media campaigns and community outreach, GTA seeks to increase knowledge and reduce stigma in communities most affected by HIV/AIDS, and provides free HIV prevention educational materials to advance this mission.

Table 1 highlights some of the key findings and lessons learned from this campaign.

Table 1.

Key findings and lessons learned

| Key Findings and Lessons Learned | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Media engagement dramatically enhances impact of faith-based HIV prevention programmes by fighting HIV/AIDS stigma and raising community HIV/AIDS awareness. |

| 2 | Together, Brown University, Philadelphia Mayor Nutter’s Office of Faith-Based Initiatives, Greater Than AIDS and 40 churches and mosques fostered an innovative HIV prevention campaign with widespread media coverage. Including leaders from across sectors dramatically broadened reach and participation in the campaign. |

| 3 | HIV testing turnout is best when faith leaders preach about HIV/AIDS, but testing may not be the most important end for the faith community in HIV prevention campaigns. Influencing social norms about HIV/AIDS and reducing stigma is equally valuable. |

| 4 | HIV prevention programmes designed for faith-based institutions should welcome diverse messages about routine HIV testing, abstinence, limiting numbers of partners and concurrent partnerships, and condom use. |

| 5 | Cultivating personal relationships and building trust with faith leaders to engage in HIV prevention is an indispensable component of any strategy engaging the faith community in HIV prevention programmes. |

| 6 | Aligning HIV prevention messaging with a national public information campaign and leveraging related resources can extend reach while helping to reduce costs related to individual (smaller scale) campaign design and implementation. |

Broad-based media approach

To raise awareness about HIV/AIDS in Philadelphia, reduce HIV/AIDS stigma, encourage HIV testing, and highlight the participation of faith-based institutions in fighting the epidemic, we developed images for billboards featuring local influential Pastors and Imams encouraging individuals to get tested in Philadelphia. We invited faith leaders from the largest congregations to participate in the billboard campaign. We also invited a leading Pastor from Black Clergy of Philadelphia and the Vicinity, a large coalition of African American clergy members in Philadelphia, and the Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) First District, which has a large presence in Philadelphia with over 300 Pastors in this 7-state district. Given the importance of HIV testing and treatment for both individual (Marks et al. 2005) and population health (Cohen et al. 2011), and the need for a concise message easily viewed and understood for drivers, we focused our central message on HIV testing. Clear Channel Outdoor donated and placed five billboards (Figure 1) in zones of Philadelphia with high HIV incidence. GTA placed an additional 106 billboards, posters, and transit shelter ads in Philadelphia with complementary messages. GTA and Clear Channel outdoor advertisements received an estimated 50 million views during a 2-month period.

Figure 1.

HIV testing billboard placed in high-incidence zones of Philadelphia (Source: Clear Channel).

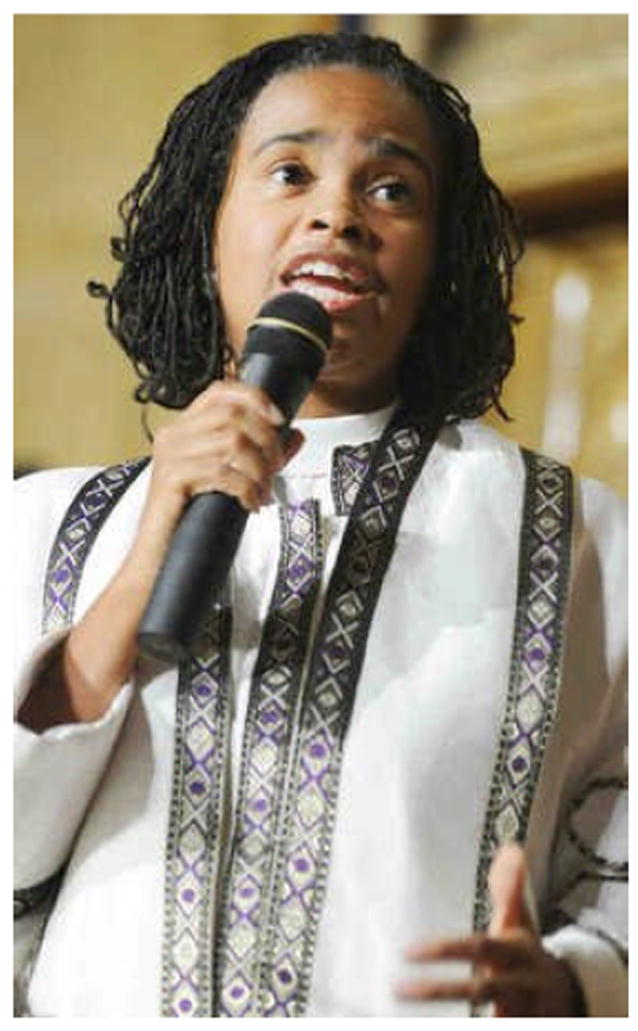

We also conducted extensive outreach to radio, print and electronic media outlets. GTA recruited local affiliates of its national media partners, Radio-One and Clear Channel Radio, to incorporate faith leaders in their community affairs programming during the campaign. Pastors conducted public service announcements and were interviewed on prominent radio stations. GTA and the Black AIDS Institute also used their websites and Facebook pages to highlight the programme. The editorial pages of Philadelphia’s two main newspapers, The Philadelphia Inquirer and The Philadelphia Tribune, (Philadelphia’s largest black newspaper) endorsed the campaign and provided coverage with numerous front-page and other articles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pastor Leslie Callahan of Saint Paul’s Baptist Church preaching about HIV/AIDS in Philadelphia as featured on the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer (Source: Philadelphia Inquirer)

Enlisting clergy requires community outreach

Churches and mosques were highly enthusiastic about engaging in HIV/AIDS prevention programmes and dozens of pastors preached about HIV during the course of the campaign. We attributed widespread participation by the Philadelphia clergy to several factors. Before the campaign launched, through focus groups and qualitative interviews, we solicited faith leaders’ inputs for the media and prevention campaign (Nunn et al. 2012b). Enlisting influential Pastors and Imams and profiling their leadership roles on bulletin boards and through media interviews raised HIV/AIDS awareness citywide and signalled that Philadelphia’s most influential pastors supported the programme. This approach helped set the appropriate tone, facilitate recruiting other clergy, promote HIV testing in many congregations who had never before hosted testing events, and link churches with existing testing events to a broader citywide effort.

HIV education and testing events

Participating faith-based institutions hosted HIV/AIDS education and prevention events. Table 2 highlights the participation of faith leaders in a variety of different HIV/AIDS prevention activities.

Table 2.

HIV prevention and awareness activities

| Effort | Number of Faith Leaders Participating N= 40 |

|---|---|

| Featured on testing billboard | 4 (10%) |

| Featured on radio public service announcement (PSA) | 7 (18%) |

| Participated in radio interview about campaign | 7 (18%) |

| Hosted an educational event about HIV/AIDS | 10 (25%) |

| Hosted an HIV testing event | 10 (25%) |

| Preached about HIV/AIDS | 30 (75%) |

| Disseminated ‘Greater than AIDS’ brochures and church or mosque bulletins | 23 (58%) |

Note: Many faith leaders participated in more than one activity of the campaign.

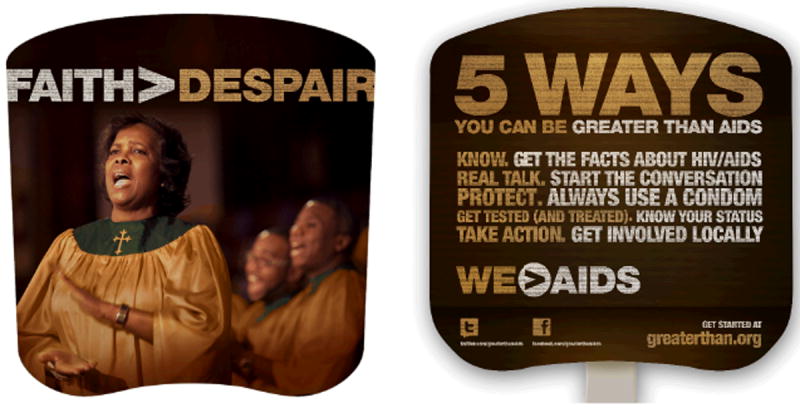

We provided churches and mosques with trained HIV testers and educators to conduct HIV/AIDS testing events that were tailored to each congregation. We also provided clergy with fact sheets about HIV/AIDS and Philadelphia’s local epidemic to inform their sermons. GTA provided participating institutions with over 13,000 informational items, including a guide and church fans that highlighted information about prevention, testing and treatment (Figure 3). We created and distributed 4,000 bulletins at participating churches and mosques about the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Philadelphia with information about local testing venues.

Figure 3.

Church fans provided by Greater than AIDS Program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (Source: Kaiser Family Foundation).

One hundred and fifty individuals underwent HIV testing at houses of worship during the campaign. Although no one was newly diagnosed with HIV, those who tested were generally at high risk by virtue of living in neighbourhoods with high prevalence rates. In addition, a large, but not readily measurable group of congregants reported that they tested at other local facilities after hearing support for testing from their ministers. Four important lessons emerged regarding HIV testing: first, testing may not be the first step in enlisting congregational support for HIV prevention; outreach to clergy and educational programmes that introduce the topic must come first. Second, HIV testing turnout was best in the congregations in which Pastors and Imams encouraged their congregations to get tested during sermons. For example, in 3 churches where pastors did not preach about HIV but who offered testing events, only 10 individuals tested for HIV. In a single church where a Pastor encouraged the congregation to test for HIV, over 100 individuals underwent HIV testing. These phenomena clearly highlighted the enormous value that preaching and leadership has on HIV testing trends. Thirdly, testing in faith-based settings may not reach the highest risk African Americans; however, enlisting clergy in HIV prevention can reduce HIV/AIDS stigma and may reach important members of social and sexual networks of individuals at high risk for contracting HIV. Perhaps most importantly, the critical role of faith-based institutions may not be offering HIV testing and other HIV/AIDS services in house; rather, combating stigma and changing social norms surrounding HIV/AIDS and encouraging HIV testing. Faith-based institutions may also play important roles in linking undiagnosed infected individuals to testing, treatment and care, support services and providing emotional and spiritual support.

Costs and sustainability

Financial outlays for this campaign were modest because of generous corporate and third party support for this programme. Brown University researchers spent $250 to print church bulletins. Philadelphia’s AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO) provided $750 to finance Clear Channel billboards. GTA covered costs for printing and staff support and received donor support from sponsors. However, the campaign required significant staff time and leadership commitments at the highest levels of city governance, clergy and academia. Expanding and sustaining this programme will require greater resource commitments; this underscores the importance of having greater National Institutes of Health (NIH) and CDC commitments for developing and implementing novel community-based HIV prevention interventions involving the faith community. However, we note that enlisting passionate, dedicated leaders committed to making public statements about HIV/AIDS was the most important component of this campaign; cultivating faith leaders will be important for applying lessons from this model in other settings.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the efforts sparked by the citywide campaign led to creation of Philly Faith in Action, a formal coalition between Brown University Medical School’s Global Health Initiative and 70 faith leaders in Philadelphia in 2011. Philly Faith in Action developed HIV testing and prevention curricula and programmes for faith audiences; developed a new social marketing campaign with clergy; created new HIV prevention materials with GTA that were launched in 2012, including new digital media platforms and faith-friendly educational materials; and sponsors many other HIV/AIDS awareness activities that take place year-round in Philadelphia. The Philly Faith in Action coalition has tested over 2,000 individuals in faith and community settings since the 2010 campaign; these efforts exemplify the importance of coalitions for sustaining and institutionalising health promotion programmes (DiClemente et al. 2009).

Embracing diverse approaches and HIV prevention messages

We encountered a wide diversity in approaches to addressing HIV/AIDS in religious contexts, particularly in relation to attitudes about human sexuality, sexual behaviour, abstinence and condom use. Faith leaders interviewed after the programme attributed the campaign’s success, including coalition-building, raising awareness, promoting testing, and its broad-based support, to tailoring evidence-based educational events for each religious institution, rather than pursuing a ‘one size fits all’ approach. For example, many pastors integrated information about the virtues of abstinence and avoiding concurrent sexual partnerships into sermons; some mentioned condom use while others preferred not to do so. We note this tailored approach is counter to many conventional ‘diffusion of evidence-based interventions’ (DEBIs) disseminated by the CDC for HIV prevention (http://www.effectiveinterventions.org/) that have historically focused on many behavioural interventions. Many evidence-based interventions are not tailored to local audiences and are often not culturally appropriate for dissemination in partnership with religious institutions. Our tailored approach was critical for enlisting support of clergy who might otherwise not have participated.

Ideally, campaigns would spark sustained community dialogue about HIV/AIDS, rather than consist only of one-time events. Some participating congregations did conduct exemplary follow-up events: for example, one large church conducted a men’s health event where 761 men from the church and community underwent HIV testing and over 1,200 participated in other prevention screenings in 2011. That event recurred in March 2012 and conducted over 985 HIV tests and 1,500 other prevention screenings. Similarly, when a mega-church Bishop recently preached about HIV/AIDS and encouraged testing, so many individuals presented for testing at the Health Fair that demand for testing outpaced the supply of tests that could be offered. Dozens of other churches from Philly Faith in Action now host regular testing and HIV/AIDS awareness events; HIV testing turnout has always been best in churches where pastors preach and encourage individuals to get tested. Taken together, these findings suggest that normalising conversations about HIV/AIDS and specifically HIV testing are feasible, but take time and require resources.

We also note that this campaign, and subsequently, a broad coalition of faith leaders called Philly Faith in Action, emerged out of a community-based participatory research project about how to effectively engage African American clergy in HIV prevention (Nunn et al. 2012a). This suggests that research, when conducted in partnership with community partners, can be an effective catalyst for social change.

Moreover, these findings underscore the importance of moving beyond a sole programmatic focus on how religious institutions can change individual behaviours, and towards an approach that addresses stigma as well as the social and economic contextual factors that contribute to racial disparities in HIV infection. Expanding federal support for community-based HIV prevention initiatives for faith-based institutions could help address this challenge.

Conclusion

New approaches to HIV prevention are critical for addressing the social and structural drivers of HIV/AIDS trends among African Americans and to accomplish the goals of President Obama’s National HIV/AIDS Strategy. Our interdisciplinary partnership of faith-based organisations, academic institutions, private sector companies, and local government to mount a city-wide HIV/AIDS awareness campaign offers lessons for a national model to engage African American clergy in HIV/AIDS prevention through media outreach; HIV/AIDS testing, education and awareness; and leadership development. Media engagement and enlisting African American faith leaders in media messaging greatly enhanced participation, helped promote testing and awareness about HIV/AIDS, and linked this initiative to GTA’s nationwide efforts to increase HIV/AIDS knowledge and reduce stigma. This citywide campaign culminated in sustained cross-cultural collaborations that continue today and could be replicated in other settings.

Faith-based institutions should be important partners in any efforts to reduce racial disparities in HIV infection and to enhance access to AIDS treatment and care services among African Americans. Successfully engaging the African American faith community in HIV prevention requires tailoring events to individual institutions rather than pursuing a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to HIV prevention. For example, the public health community should embrace diverse messages about human sexuality, abstinence, routine testing, AIDS treatment and retention in care, partner concurrency and partner reduction strategies as important tools for HIV prevention in faith-based contexts.

The NIH and CDC should support more robust research and programmatic agendas grounded in community-based approaches to HIV prevention in partnership with the African American faith community. Engaging African American faith institutions in HIV prevention requires extensive community outreach; developing relationships with faith leaders and cultivating community champions and will be essential to advance research and programmatic collaborations to address the African American HIV/AIDS epidemic. Sustaining such efforts will require more resources, but above all, requires engaged community leaders.

Acknowledgments

Development of this manuscript was supported by the MAC AIDS Fund, grant numbers K01 AA020228–01A1 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health (NIAAA/NIH) and grant number P30-AI-42853 from the National Institutes of Health, Center for AIDS Research (NIH/CFAR). None of the aforementioned agencies had any design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):337–340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltri JM, Davis-Smith M, Okosun IS, Seale JP, Foster B. Translation of the National Institutes of Health diabetes prevention program in African American churches. Journal of the National Medical Association. Year;103(3):194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buta B, Brewer L, Hamlin DL, Palmer MW, Bowie J, Gielen A. An innovative faith-based healthy eating program: from class assignment to real-world application of PRECEDE/PROCEED. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(6):867–875. doi: 10.1177/1524839910370424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV testing in the United States. Atlanta: Publisher; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Late versus early testing of HIV--16 sites, United States, 2000-2003. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52(25):581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS in the United States: a picture of today’s epidemic. Atlanta: Publisher; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Characteristics associated with HIV infection among heterosexuals in urban areas with high AIDS prevalence --- 24 cities, United States 2006--2007. Atlanta: Publisher; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin JJ, Li MY, Kang E, Behar E, Chen PC. Civic/sanctuary orientation and HIV involvement among Chinese immigrant religious institutions in New York City. Global Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 2):S210–S226. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.595728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, Mccauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, Godbole SV, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos BR, Mayer KH, Hoffman IF, Eshleman SH, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J, Mills LA, De Bruyn G, Sanne I, Eron J, Gallant J, Havlir D, Swindells S, Ribaudo H, Elharrar V, Burns D, Taha TE, Nielsen-Saines K, Celentano D, Essex M, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JD, Lindley LL, Annang L, Saunders RP, Gaddist B. Development of a framework for HIV/AIDS prevention programs in African American churches. AIDS Patient Care STDS. Year;26(2):116–124. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Kerrigan D, Mcneely C, Ellen J. The role of structure versus individual agency in churches’ responses to HIV/AIDS: a case study of Baltimore city churches. [Day Month Year];Journal of Religious Health. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9281-7. [online]. Available from: website. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DS, Goldmon MV, Coker-Appiah DS. Using a community-based participatory research approach to develop a faith-based obesity intervention for African American children. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(6):811–822. doi: 10.1177/1524839910376162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaven MJ, Ramos-Roman MA, Gimpel N, Carson J, Delemos J, Pickens S, Simmons C, Powell-Wiley T, Banks-Richard K, Shuval K, Duval J, Tong L, Hsieh N, Lee JJ. The goodnews (genes, nutrition, exercise, wellness, and spiritual growth) trial: a community-based participatory research (cbpr) trial with African-American church congregations for reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors--recruitment, measurement, and randomization. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2011;32(5):630–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diclemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim SH, Anderson JE, Weidle P, Purcell DW. Race/ethnic disparities in HIV testing and knowledge about treatment for HIV/AIDS: United States, 2001. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18(1):27–33. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25(6):700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PP, Cooper K, Parton JM, Meeks JO. Assessment of HIV/AIDS prevention of rural African American Baptist leaders: implications for effective partnerships for capacity building in American communities. Journal of the National Medical Association. Year;103(4):323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PP, Gaskins SW. Older African Americans’ management of HIV/AIDS stigma. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1306–1312. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Karon J, Brookmeyer R, Kaplan EH, Mckenna MT, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18677024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Survey of American on HIV/AIDS. Washington, DC: Publisher; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Mccullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Religion, health and medicine in African Americans: Implications for physicians. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(2):237–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. God, faith and health: exploring the spirituality-healing connection. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat RV, Losina E, Kang M, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Refusing HIV testing in an urgent care setting: results from the “think HIV” program. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2006;20(2):84–92. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln C, Mamiyam L. The black church in the African American experience. Durham: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2005;39(4):446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Laboy M, Garcia J, Moon-Howard J, Wilson PA, Parker R. Religious responses to HIV and AIDS: understanding the role of religious cultures and institutions in confronting the epidemic. Global Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 2):S127–31. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.602703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAACP. [Day Month Year];The black church and HIV: the social justice imperative. Year [online]. Available from: http://naacp.3cdn.net/93e02bcd4b6cef2aad_pam6yxw29.pdf.

- Nunn A, Cornwall A, Chute N, Sanders J, Thomas G, James G, Lally M, Trooskin S, Flanigan T. Keeping the faith: African American faith leaders’ perspectives and recommendations for reducing racial disparities in HIV/AIDS infection. PLoS One. 2012a;7(5):e36172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036172. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22615756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Cornwall A, Chute N, Sanders J, Thomas G, Lally M, Trooskin S, Flanigan T. Keeping the faith: African american faith leaders’ perspectives and recommendations for reducing racial disparities in hiv/aids infection. PLoS ONE. 2012b doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036172. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Eng W, Cornwall A, Beckwith C, Dickman S, Flanigan T, Kwakwa H. African American patient experiences with a rapid HIV testing program in an urban public clinic. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2012c;104(1-2):5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30125-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22708242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Eng W, Cornwall A, Dickman S, Beckwith C, Flanigan T, Kwakwa H. African American patient experiences with a rapid HIV testing program in an urban public clinic. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011a doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30125-5. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Zaller N, Cornwall A, Mayer KH, Moore E, Dickman S, Beckwith C, Kwakwa H. Low perceived risk and high HIV prevalence among a predominantly African American population participating in philadelphia’s rapid HIV testing program. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2011b;25(4):229–235. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0313. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21406004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Aids Policy. The national HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Washington, DC: Publisher; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pew. The Pew forum on us religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Publisher; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Feyler N, Baker J, Brady K. HIV and AIDS in the city of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Publisher; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Palar K, Derose KP. Congregation-based programs to address HIV/AIDS: elements of successful implementation. [Day Month Year];Journal of Urban Health. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9526-5. [online], Epub ahead of Print (Feb 11, 2011), Available from: website. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Wittlin NM, Munoz-Laboy M, Parker R. Ideologies of black churches in New York City and the public health crisis of HIV among black men who have sex with men. Global Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 2):S227–S242. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.605068. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21892894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeary KH, Cornell CE, Turner J, Moore P, Bursac Z, Prewitt TE, West DS. Feasibility of an evidence-based weight loss intervention for a faith-based, rural, African American population. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2011;8(6):A146. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22005639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]