Summary

Vascular injury is an unusual and serious complication of transsphenoidal surgery. We aimed to define the role of angiography and endovascular treatment in patients with vascular injuries occurring during transsphenoidal surgery.

During the last ten-year period, we retrospectively evaluated nine patients with vascular injury after transsphenoidal surgery. Eight patients were symptomatic due to vascular injury, while one had only suspicion of vascular injury during surgery. Four patients presented with epistaxis, two with subarachnoid hemorrhage, one with exophthalmos, and one with hemiparesia. Emergency angiography revealed a pseudoaneurysm in four patients, contrast extravasation in two, vessel dissection in one, vessel wall irregularity in one, and arteriovenous fistula in one. All patients but one were treated successfully with parent artery occlusion, with one covered stent implantation, one stent-assisted coiling method, while one patient was managed conservatively. One patient died due to complications related to the primary insult without rebleeding.

Vascular injuries suspected intra or postoperatively must be investigated rapidly after transsphenoidal surgery. Endovascular treatment with parent artery occlusion is feasible with acceptable morbidity and mortality rates in the treatment of vascular injuries occurring in transsphenoidal surgery.

Key words: pituitary gland, neoplasms, transsphenoidal surgery, endovascular, embolization

Introduction

Transsephenoidal surgery (TSS) has become increasing popular in sellar tumor treatment. Hemorrhagic complications during or after transsphenoidal surgery are rare, but when they occur they may lead to permanent disability or death 1. Although experience and thorough knowledge of the relevant anatomy can prevent many potential complications associated with TSS, the risk of arterial injury cannot be completely eliminated, especially given the large number of such procedures performed and the complexity of certain cases.

Traditionally, emergency surgical ligation has been used to treat internal carotid artery (ICA) injury. This treatment itself, however, is associated with an unacceptable incidence of major complications, such as death and stroke 2,3, and it is often an ineffective or even harmful treatment for ICA injury. Recent advances in endovascular techniques have, however, created alternatives to this traditionally high-risk technique 3. We aimed to define the role of endovascular treatment in patients with vascular injuries occurring during TSS.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively studied the medical records and angiographic findings of nine patients (four women, five men; age range, 18-71 years, mean 54 years) with vascular injury after TSS. The patients were referred for diagnosis or endovascular treatment of vascular injury from either three state training hospitals or one university (our center) hospital in our city, or three other university hospitals located in the neighboring cities. Postoperative angiography was performed early after surgery in five patients or after a delayed period in four patients. Angiographic findings were labeled as showing carotid occlusion, stenosis, carotid cavernous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, and contrast extravasation. Opacification of a pouch was labeled as pseudoaneurysm (PA), while unusual extension of contrast medium without any shape was defined as extravasation.

Results

Patient information, presenting symptoms, bleeding episodes, angiographic findings, treatment and outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient information.

| Case | Age/ Sex |

Cavernous sinus invasion on MRI |

Presenting symptoms (Postoperative timing) |

Angiographic findings |

Treatment (Technique) |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60/M | Yes | SAH (2nd day) | PCA P1 PA | PAO (coiling) | Good |

| 2 | 60/F | Yes (clivus invasion also) |

Epistaxis (day 23) | Basilar trunk PA |

Aneurysm occlusion (stent- assisted coiling) |

Good |

| 3 | 18/F | None | Hemiparesia (day 1) | Distal ICA dissection and luminal thrombus |

PAO (detachable balloon) |

Good |

| 4 | 46/M | Yes | Exophthalmos (day 15) | Direct CCF | Fistula occlusion (covered stent) |

Good |

| 5 | 37/F | None | SAH (day 10) | ACA A1 PA and ipsilateral occluded ICA |

PAO (coiling) | Hemiparesia |

| 6 | 69/M | None | Epistaxis (day 9) | Cavernous ICA PA |

PAO (coiling) | Death on day 12 |

| 7 | 57/M | None | Suspicion of vessel injury (day 1) |

Cavernous ICA focal stenosis (on first and 15th day) |

Diagnostic angiography (none) |

Good |

| 8 | 69/F | None | Epistaxis (day 3) | Cavernous ICA extravasation |

PAO (coiling) | Good |

| 9 | 71/M | None | Epistaxis (day 1) | Cavernous ICA extravasation |

PAO (detachable balloon) |

Good |

|

Note: ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; CCF, carotid cavernous fistula; PA, pseudoaneurysm; PAO, parent artery occlusion. | ||||||

Among the nine cases, intraoperative arterial injury occurred in six patients. Two of the six events resulted in early termination of the operation. The remaining three patients had no evidence of vascular injury during the operation, but became symptomatic later. Four of the eight symptomatic patients presented in the late postoperative period; two severe epistaxis, one SAH, and one exophthalmos.

Parent artery occlusion (PAO) was the main endovascular strategy (six out of nine patients) in our population. One PAO was applied on the posterior communicating artery (PCA) P1 segment PA (case 1) without vascular compromise because of the good collateral supply from the PCA. Another PAO was applied on the ACA A1 segment PA (case 5) (the ipsilateral ICA had been clipped before); the patient experienced moderate (thanks to good pial collaterals) hemiparesia. The remaining four PAOs were applied on the cavernous ICA. The collateral circulation was assesses successfully by contralateral carotid and one vertebral angiography and by ipsilateral manual carotid compression in two of these four patients. The detachable coils were used as embolization devices in these four PAO patients. The technique consisted of filling the aneurysm first and then sealing the parent artery. After unsuccessful manual compression or suspicion of insufficient collateral circulation with compression, the last two patients had balloon occlusion of the ICA. A 30 minute occlusion test was performed, during which tolerance was assessed by clinical examination, and collateral circulation was assessed by angiography, using the contralateral femoral artery. After passing the test occlusion, the balloon was detached at the cavernous ICA and a second security balloon detached at the petrous ICA. PAO of the ICA was performed without permanent complications and without recurrence. Only one patient (case 9) had transient hemiparesis 24 hours after balloon occlusion with no sequel. Besides the six PAOs and one conservative patient, the vascular injury of the remaining two patients was treated by parent artery preservation. We used a stent-assisted coiling technique in one PA located on the basilar artery (case 2) and covered stent implantation across the vascular defect in a carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) patient (case 4). All endovascular treatments but one were performed under emergency conditions without any special preparations. The last patient with vascular injury (case 4) presenting one month after TSS (15 days after initiation of symptoms) was managed electively. Due to being in the late phase of vascular injury, this patient was loaded with 450 mg clopidogrel and 100 mg aspirin six hours before the procedure, and a covered stent was deployed successfully with fistula occlusion.

The follow-up period varied from 30 days to ten years. None of the patients re-bled during the follow-up period.

One patient died of complications related to primary and associated pathology even after permanent endovascular bleeding control (case 6). One patient had residual deficits at follow-up (case 5), the remaining seven patients had a good outcome.

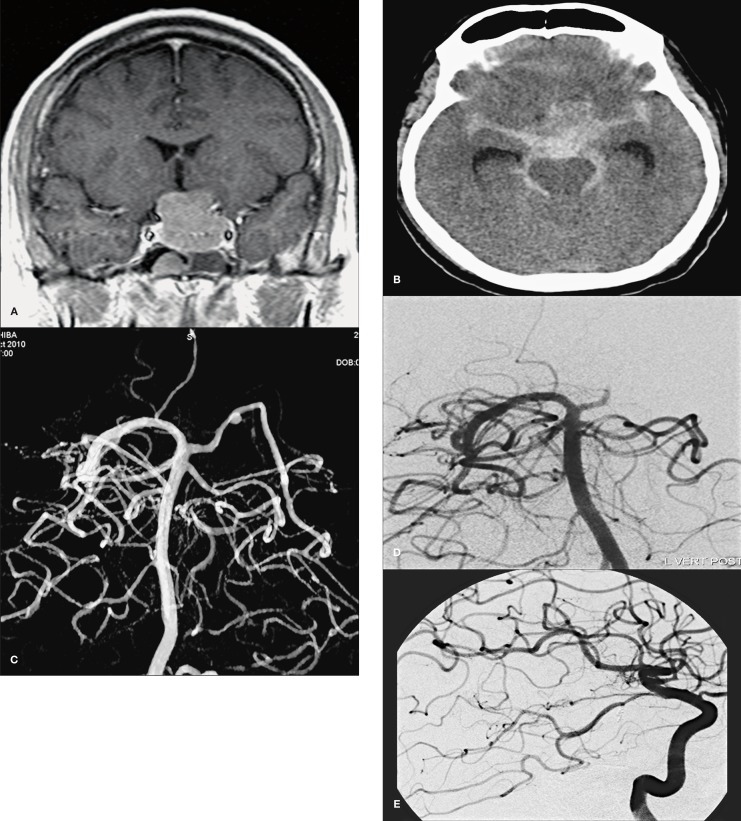

Figure 1.

Case 1. Preoperative postcontrast coronal T1-weighted MR image showing a pituitary tumor that had suprasellar extension (A). Post operative CT image shows diffuse subarachnoid haemorrhage in all basal cisterns (B). 3D rotational angiography showed a ruptured small aneurysm of the left P1 (C). Control angiography showed complete occlusion of the aneurysm (D) with total preservation of the posterior communicating artery and left posterior cerebral artery (E).

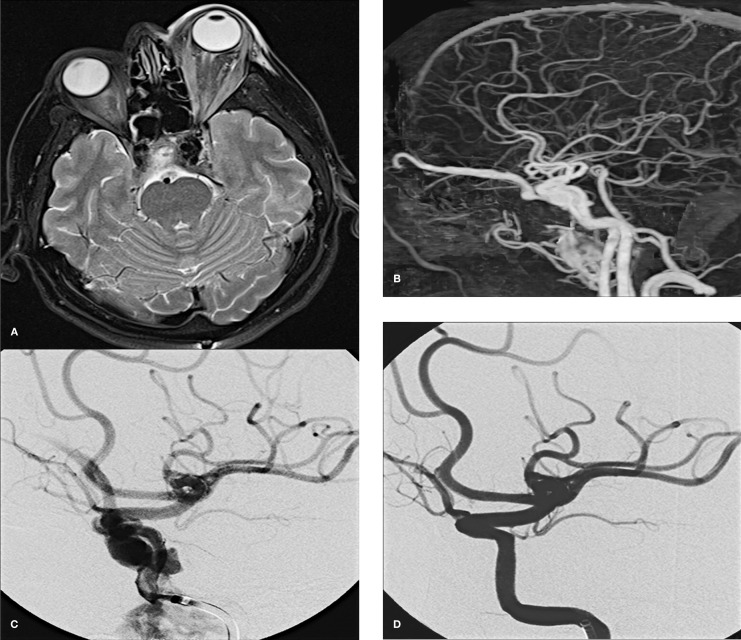

Figure 2.

Case 4. Postoperative axial T2-weighted MR image showing anexophthalmos of the left eye (A). Reconstructed MIP of the subtracted images from CTA (B). Left carotid angiogram shows a direct CCF mainly draining to the superior ophtalmic vein (C). Postprocedural left CCA angiogram obtained after deployment of stent-graft reveals cessation of contrast material extravasation and closure of the CCF (D).

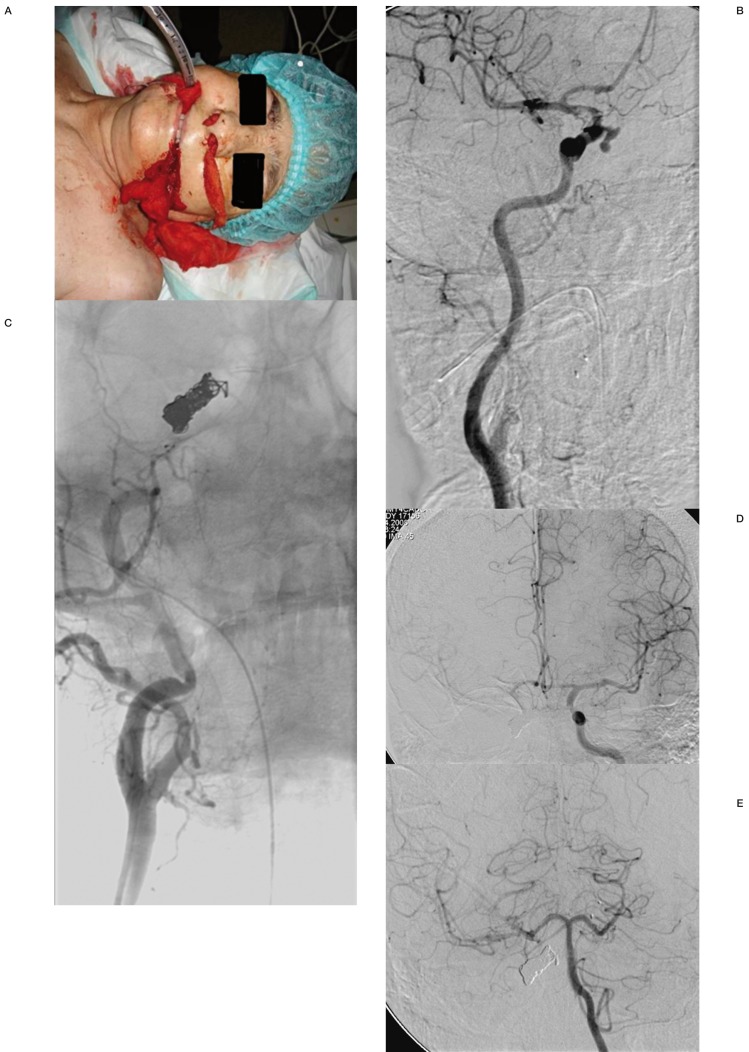

Figure 3.

Case 6. Post-operative active bleeding following transnasal surgery (A). Oblique CCA angiography showed the active extravasation of contrast from the right cavernous ICA(B). Right common carotid angiography after coil embolization of the internal carotid artery (C). Left internal carotid (D) and vertebral angiography (E) during occlusion shows adequate anterior and posterior communicating artery collateral filling. Permanent carotid occlusion was performed with no further episode of bleeding.

Discussion

Due to the proximity of the cavernous ICA to the bony wall of the sphenoid sinus and sella, the vessel is particularly susceptible to injury during transsphenoidal procedures, which has the potential to lead to catastrophic complications. Depending on the tortuosity of the cavernous carotids, both sides may actually come into contact centrally within the sella (“kissing carotids”), just behind the dura mater. In such circumstances, they are especially vulnerable to injury when the sellar dura is opened and the pituitary lesion exposed. Therefore, perforation or laceration of the cavernous ICA are the most common types of injury in TSS 4.

This kind of direct trauma to the carotid can subsequently result in pseudoaneurysm (PA) formation, even if the artery appears to be structurally intact, packed, and not bleeding intra-operatively 2. Fortunately, vascular injuries are uncommon in TSS, estimated to occur in just 1.1% of all cases 5. Other conditions associated with increased risks of vascular injury include anatomic variants of the sphenoid bones, tumor invasion of the cavernous sinus, tumor adhesion to the ICA, and distortion of the local anatomy 6. As such, it is critical to remain in the midline during TSS, and the vomer ridge can be used as an important landmark. Extreme care must be exercised at the boundaries of the tumor, especially laterally, during all aspects of the operation 2. In a series of 3,061 TSS, just one case of PA development was reported 7. Similarly, another study of surgical complications in a series of 146 patients with pituitary adenomas undergoing TSS noted only a single case of PA formation 8. In case of vascular injury during TSS, prompt recognition and emergency treatment are essential for avoiding further complications such as rupture of PA, subarachnoid or extradural hemorrhage, stroke due to thromboemboli, and even death 9,10.

In the event of intraoperative carotid injury, the carotid artery is compressed to give sufficient time for tamponade with a variety of materials (including Surgicel, muscle plugs, tissue adhesives), which are held in place by closing the sellar window with a piece of cartilage or bone. If significant bleeding occurs during or after a TSS, even after successful intraoperative tamponade, immediate vascular imaging should be obtained and the clues of vessel wall damage must be sought 2,4,6. Moreover, if intraoperative packing was utilized for hemorrhage control, any radiographic studies that appeared normal with the packing in place should be repeated later regardless of pack removal 4. According to the literature, ICA injuries typically present at the time of initial injury 2. Our findings are consistent with the literature: six out of nine cases in our review were characterized by substantial intraoperative vascular injury. Fatal or life-threatening epistaxis occurred as much as two and ten years after TSS. These delayed events, despite satisfactory initial control, illustrate the need to examine all patients by vascular imaging after TSS that has been complicated by profuse bleeding or followed by epistaxis. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance or computed tomography angiography have been suggested as a quick, non-invasive surveillance methods well-suited for this purpose 10. However, it should be kept in mind that digital subtraction angiography is the gold standard for vascular diagnosis, especially in intracranial circulations.

Life-threatening perioperative bleeding was controlled initially in all cases by vigorous packing with a variety of materials. Packing may be difficult when all bony structures are destroyed by giant invasive lesions. “Over-packing” was associated with complete carotid occlusion, carotid stenosis, and basilar artery compression, and it may have contributed to postoperative ophthalmoplegia and optic nerve injury in some cases 11. These secondary complications appear difficult to prevent, since packing has to continue until life-threatening hemorrhage is effectively controlled. One of our patients (case 7) had a focal ICA cavernous segment stenosis without clinical consequences due to the over-packing. Although most arterial injuries were recognized and controlled at the time of TSS, three patients had vascular lesions that remained unnoticed until they caused massive epistaxis (two patients) and SAH (one patient). Five other patients thought to have been controlled intraoperatively, later became symptomatic (two epistaxis, one SAH, one CCF, one hemiparesia).

Carotid occlusions and stenoses on postoperative angiograms are probably caused either by tight packing or arterial wall injury. Reversibility of the occlusion, variations in the degree of stenosis, and return to a normal appearance in time suggest a variable and possibly temporary host reaction, such as local spasm, mural hematoma, dissection, or partial thrombosis. Possible recanalization may expose the patient to risks of cerebral emboli, PA formation, and recurrence of hemorrhagic episodes. Intraluminal thrombus with embolic consequences was encountered in one patient with carotid dissection (case 3). We now consider this finding to be a significant lesion that should be treated by permanent balloon occlusion of the parent artery, if there is a good collateral circulation.

Four patients (two ICA, one basilar artery, one ACA A1 segment) had the typical angiographic appearance of a PA. These lesions have been reported in patients after TSS 4-6. This is the most dangerous vascular complication and since it is not a real aneurysm and lacks a wall, it should be treated by PAO 4. An attempt at endovascular occlusion of a PA with preservation of the carotid artery has been reported 12. Similarly, attempts to preserve the carotid artery in cases of carotid cavernous fistulas have been reported followed by massive epistaxis 4-6.

Considering PAO, the detachable balloon technique is well-established and has been practised for many years 9,13,14. Controlled endovascular occlusion is more predictable than intraoperative occlusion by packing and permits a test occlusion of the carotid artery to minimize ischemic complications. Carotid occlusion under emergency conditions is not without risks. One of our patients suffered transient ischemic complications despite a negative test occlusion. It is worth noting that five to 20% of patients who tolerate balloon test occlusion will still have ischemic complications after ICA occlusion 15. Despite an incomplete circle of Willis, we elected to sacrifice the parent artery in one patient (case 5) for anatomical reasons.

There is a wide variety of endovascular techniques, other than PAO, which may be employed to treat vascular injuries after TSS, including coil embolization 8,10,16, stent-assisted coiling 6,17, covered stent placement 18, and Onyx embolization 19, most of which were utilized by the cases in this series. With regard to treatment with parent artery-sparing options as mentioned above, delayed-onset recanalization over the course of many months is a well-documented phenomenon that may lead to aneurysm rupture and even death 15,17. Therefore all patients undergoing parent artery-sparing treatment must be followed up angiographically within six months after treatment.

In terms of covered stent-grafts, numerous reports documenting success are available in the literature 18,20,21. However, this covered stent is not designed for intracranial use and some concern exists regarding its long-term safety and efficacy. Nonetheless, a recent study documented the successful use of a new covered stent, designed for the intracranial vasculature, in eight patients with intracranial carotid PA 22. In case of CCF with favorable vascular anatomy, the balloon expandable stent-graft may be an alternative option as a parent artery-sparing technique, as in case 4 in our series. Occlusion with detachable balloons and simple or stent-assisted coil occlusion of the fistula are other available parent artery-sparing techniques in case of CCF.

Conclusions

The presence of either an intraoperative suspicion of vessel injury or any neurologic symptoms/bleeding after TSS must prompt us to perform a rapid search for vascular injury with subsequent emergency endovascular treatment. Parent artery occlusions appear to be a definitive treatment method with good clinical results in most patients. Patients should be treated on a case-by-case basis, with optimization of the available resources.

References

- 1.Zervas NT. Surgical results for pituitary adenomas: results of an international survey. In: Black PMcL, Zervas NT, Ridgway EC, Jr, et al., editors. Secretory tumors of the pituitary gland. New York: Raven Press; 1984. pp. 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raymond J, Hardy J, Czepko R, et al. Arterial injuries in transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma, the role of angiography and endovascular treatment. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaloupka JC, Putman CM, Citardi MJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for the carotid blowout syndrome in head and neck surgical patients: diagnostic and managerial considerations. Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:843–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahuja A, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Carotid cavernous fistula and false aneurysm of the cavernous carotid artery, complications of transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:774–778. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199210000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciric I, Ragin A, Baumgartner C, et al. Complications of transsphenoidal surgery results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:225–236. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199702000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciceri EF, Regna-Gladin C, Erbetta A, et al. Iatrogenic intracranial pseudoaneurysms: neuroradiological and therapeutical considerations, including endovascular options. Neurol Sci. 2006;27:317–322. doi: 10.1007/s10072-006-0703-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laws ER. Vascular complications of transsphenoidal surgery. Pituitary. 1999;2:163–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1009951917649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Colao A, et al. Surgical complications associated with the endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for pituitary adenomas. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:293–298. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.2.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pozzati E, Giuliani G, Poppi M, et al. Blunt traumatic carotid dissection with delayed symptoms. Stroke. 1989;20:412–416. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buerke B, Tombach B, Stoll W, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography follow-up examinations to detect iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms following otorhinolaryngological surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:698–701. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107006780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ducruet AF, Hickman ZL, Zacharia BE, et al. Intracranial infectious aneurysms: a comprehensive review. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s10143-009-0233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solheim O, Selbekk T, Lovstakken L, et al. Intrasellar ultrasound in transsphenoidal surgery: a novel technique. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:173–185. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000360571.11582.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng KY, Lee KW, Chiang FY, et al. Rupture of radiation induced-internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with nasopharyngeal carcinoma spontaneous occlusion of carotid artery due to long-term embolizing performance. Head Neck. 2008;30:1132–1135. doi: 10.1002/hed.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley RW, Dumont AS, Jane JA., Jr Bilateral intracavernous carotid artery pseudoaneurysms as a result of sellar reconstruction during the transsphenoidal resection of a pituitary macroadenom, case report. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52:44–48. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1104611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadyrov NA, Friedman JA, Nichols DA, et al. Endovascular treatment of an internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm following transsphenoidal surgery. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:624–627. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.3.0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanninen RL, Manninen HI, Rinne J. Intrasellar iatrogenic carotid pseudoaneurysm: endovascular treatment with a polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:298–301. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-2728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hattori I, Iwasaki K, Horikawa F, et al. Treatment of a ruptured giant internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm following transsphenoidal surgery: case report and literature review. No Shinkei Geka. 2006;34:1141–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saatci I, Cekirge HS, Ozturk MH, et al. Treatment of internal carotid artery aneurysms with a covered stent: experience in 24 patients with mid-term follow-up results. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1742–1749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahuja V, Tefera G. Successful covered stent-graft exclusion of carotid artery pseudo-aneurysm: two case reports and review of literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medel R, Crowley RW, Hamilton DK, et al. Endovascular obliteration of an intracranial pseudoaneurysm: the utility of Onyx. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:445–448. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.PEDS09104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Struffert T, Buhk JH, Buchfelder M, et al. Coil migration after endovascular coil occlusion of internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysms within the sphenoid sinus. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52:89–92. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li MH, Li YD, Gao BL, et al. A new covered stent designed for intracranial vasculature: application in the management of pseudoaneurysms of the cranial internal carotid artery. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1579–1585. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]