Abstract

Background

A potential link between intimate partner violence (IPV) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been suggested, yet evidence is scarce. We assessed cardiovascular risk and incident prescription of cardiovascular medication by lifetime experiences of physical and/or sexual IPV and psychological IPV alone in women.

Methods

A population-based cohort study of women aged 30–60 years was performed using cross-sectional data and clinical measurements from the Oslo Health Study (2000–2001) linked with prospective prescription records from the Norwegian Prescription Database (January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2009). We used age-standardized chi-square analyses to compare clinical characteristics by IPV cross-sectionally, and Cox proportional hazards regression to examine cardiovascular drug prescription prospectively.

Results

Our study included 5593 women without cardiovascular disease or drug use at baseline. Altogether 751 (13.4%) women disclosed IPV experiences: 415 (7.4%) physical and/or sexual IPV and 336 (6.0 %) psychological IPV alone. Cross-sectional analyses showed that women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV and psychological IPV alone were more often smokers compared with women who reported no IPV. Physical and/or sexual violence was associated with abdominal obesity, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides. The prospective analysis showed that women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV were more likely to receive antihypertensive medication: incidence rate ratios adjusted for age were 1.27 (95% confidence interval 1.02–1.58) and 1.36 (CI 1.09–1.70) after additional adjustment for education and systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respectively. No significant differences were found for cardiovascular drugs overall or lipid modifying drugs.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that clinicians should assess the cardiovascular risk of women with a history of physical and/or sexual IPV, and consider including CVD prevention measures as part of their follow-up.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as actual or threatened physical, sexual, or psychological abuse by a current or former intimate partner.1 In a national study in Norway one in four ever-partnered women reported lifetime experiences of IPV2; in other geographical areas the prevalence ranges from 10% to 71%.3,4 A growing body of evidence links IPV with a broad range of adverse health outcomes and risk behaviors in women.5 IPV is therefore considered as an important contributor to the global burden of disease in women.6,7

The leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide is cardiovascular disease (CVD).8 Important risk factors for CVD include age, sex, smoking, overweight, physical inactivity, raised blood pressure, abnormal blood lipids, diabetes, and hereditary factors.9 Researchers have hypothesized different potential pathways from IPV to increased cardiovascular risk; for instance, through health risk behaviors such as smoking or stress-induced alterations in the endocrine and immune response.10,11 At present, there is little research on cardiovascular health in relation to IPV, yet former studies indicate that IPV is associated with certain risk factors for CVD. Prior investigations have consistently documented that women who have experienced IPV are more likely to smoke,12–14 while there is conflicting evidence for an association between IPV and hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.14–16 Despite a conceptual link between IPV and CVD, substantial gaps of evidence remain. Firstly, most previous investigations have relied exclusively on self-reported data, and lacked objective clinical measures of cardiovascular health. Secondly, former studies have generally included nonrandom samples recruited from clinics, shelters, or police records, hence population–based evidence is requested. Thirdly, current knowledge is primarily based on cross-sectional research. Prospective studies are therefore needed to establish a temporal relationship and potentially understand causal pathways between IPV and health disorders. Finally, previous research has mainly focused on IPV comprising physical and/or sexual violence. Emerging findings suggest that also psychological IPV alone is prevalent and associated with adverse health effects and should accordingly receive more attention.17–21

We did a population based cohort study of women aged 30–60 years with no CVD or cardiovascular drug use at baseline, using information about socioeconomic status, health, IPV, and clinical measurements from the Oslo Health Study (HUBRO) linked with longitudinal, register-based prescription data. Our aims were to investigate whether there was a relationship between lifetime experiences of physical and/or sexual IPV or psychological IPV alone and (1) women's cardiovascular risk (cross-sectional analysis), and (2) incident cardiovascular drug treatment (prospective analysis).

Materials and Methods

Data sources and study population

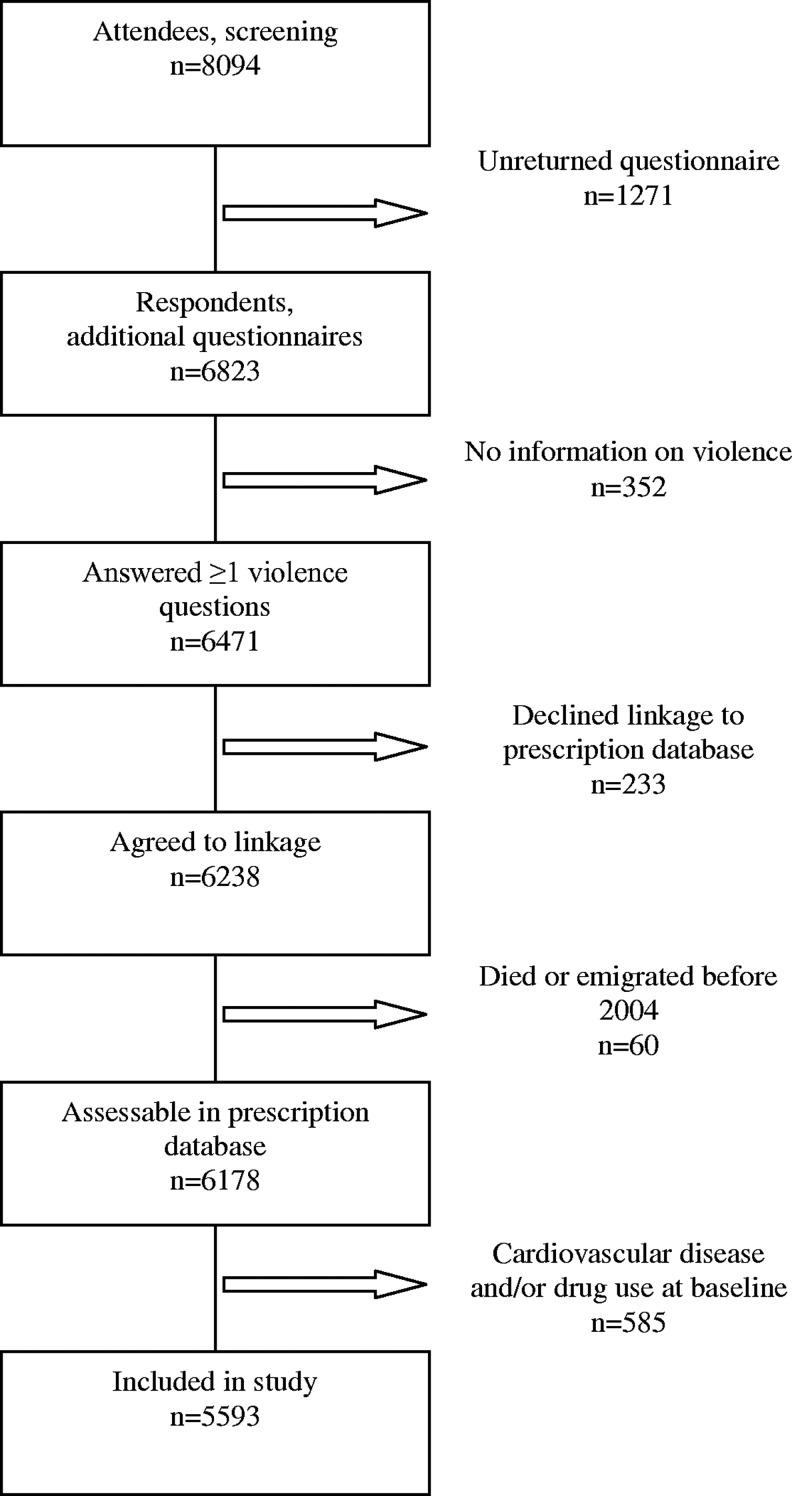

HUBRO has been described in detail elsewhere.19,22,23 In brief, it was conducted in the city of Oslo in 2000–2001 through joint collaboration of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, the University of Oslo, and the Municipality of Oslo. All residents from selected age cohorts were invited to participate. They initially received a main questionnaire and an invitation for a medical screening examination by mail. At the screening the completed main questionnaire was collected, and supplementary questionnaires were handed out to be answered at home and returned by mail in a prepaid envelope. The HUBRO questionnaires covered socioeconomic status, current and past health, lifestyle, health service and drug use, and life events. Women born in 1940, 1941, 1955, 1960, and 1970 were also asked about violence in the supplementary questionnaires. Altogether, 8094 (48%) of 16,926 invited women attended screening and thus received supplementary questionnaires. Overall 6471 women answered questions on violence; i.e., 80% of women who received supplementary questionnaires, and 38% of women who were originally invited. In total, 2501 (31%) screening attendees were excluded: 1271 (16%) did not return the questionnaires, 352 (4%) returned questionnaires without answering questions on violence, 233 (3%) declined linkages to the Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD), 60 (1%) died or emigrated before 2004, and 585 (7%) reported CVD or cardiovascular drug use in HUBRO. Hence our study included 5593 women without cardiovascular disease or drug use at baseline (Fig. 1). Among the excluded women, physical and/or sexual IPV was associated with angina pectoris; otherwise there were no statistically significant differences with respect to IPV and myocardial infarction, stroke/cerebral hemorrhage, or cardiovascular drug use (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of the study sample selection.

NorPD covers the entire population of Norway and provides information about all prescriptions dispensed to individuals living outside institutions.24 For each prescription, there is information on encrypted identifiers for patients and prescribers, dispensing date, and detailed drug data. Drugs are classified by their Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code.25 Records of cardiovascular drug prescriptions were drawn from NorPD from its inauguration on January 1, 2004, until December 31, 2009. We obtained data on participants' date of death or emigration from Statistics Norway until 2006; later date of death was retrieved from NorPD. Data from HUBRO, NorPD and Statistics Norway were linked with the unique 11-digit identity number of Norwegian citizens. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate. All participants gave written informed consent.

Variables

Lifetime experiences of IPV was the exposure variable in this study. The Oslo Health Study included five questions on violence that were adapted from a more comprehensive questionnaire developed to assess abuse among women in the Nordic countries26:

1. Have you ever been systematically intimidated, degraded, or humiliated over a long period of time?

2. Have you ever experienced threats to harm you or someone close to you?

3. Have you ever been physically attacked/abused?

4. Have you ever been forced into sexual activities?

5. Has anyone ever raped you or tried to rape you?

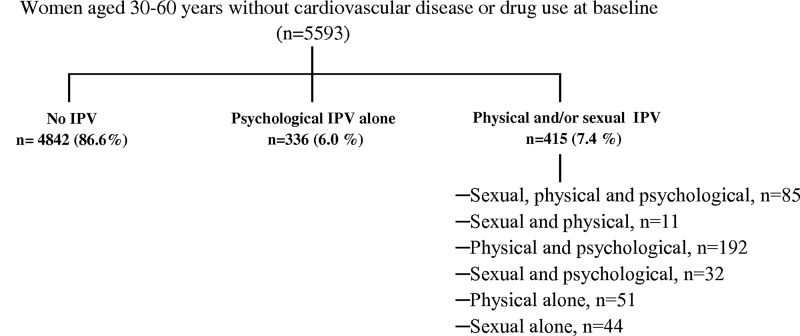

Response alternatives were “No,” “Yes, below 18 years of age,” and “Yes, 18 years or above.” All questions 1–5 included explicit questions about perpetrator (stranger, family/relative, partner, friend/acquaintance) and time of exposure (less vs. more than 12 months ago). A positive answer to question 1 and/or 2 was defined as psychological violence, 3 as physical violence, and 4 and/or 5 as sexual violence. Violence was defined as IPV when the woman reported her partner as the perpetrator. IPV was further classified as physical and/or sexual IPV if the woman answered yes to question 3, 4, and/or 5, as psychological IPV alone if she answered yes to question 1 and/or 2 and no to questions 3–5, and no IPV (reference) if she answered no to all questions 1–5. The category physical and/or sexual IPV may also have included psychological IPV (Fig. 2). The IPV classification complied with recommendations of distinguishing IPV that involves physical and/or sexual violence from psychological IPV alone.27

FIG. 2.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) exposure groups.

Cardiovascular drugs comprised drugs with ATC codes C01 (cardiac therapy), C02 (antihypertensives), C03 (diuretics), C04 (peripheral vasodilators), C07 (beta blocking agents), C08 (calcium channel blockers), C09 (agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system), and C10 (lipid-modifying agents). Drugs with ATC codes C02, C03, C07, C08, and C09 were further classified as antihypertensive drugs. Incident use of cardiovascular drugs, antihypertensive drugs, or lipid-modifying drugs was defined as filling at least one prescription of cardiovascular drugs, antihypertensive drugs, or lipid-modifying drugs respectively during January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2009, with women with previous CVD or cardiovascular drug use excluded.

CVD risk was assessed by Framingham 10-year risk of general cardiovascular disease.28 This is a clinical risk score based on age, sex, diabetes, smoking, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. It can be used to quantify risk and to guide preventive care for individuals aged 30–74 years with no CVD at baseline. In the bivariate analysis, CVD risk was divided into quartiles based on the estimated risk of the entire sample. Women who reported that their mother, father, brother, sister, or child had suffered from heart attack before the age of 60 and/or from stroke or cerebral hemorrhage were classified as having CVD in family. Alcohol use was assessed by a question on past year's drinking frequency. There were originally eight response alternatives which we collapsed into three categories: 4–7 times a week, <4 times a week, and no use last year. The participants were classified as (1) inactive if they reported less than 1 hour of hard and less than 3 hours of light physical activity per week, (2) moderately active if they reported 1 to 3 hours of hard or >3 hours of light activity per week, and (3) physically active if they reported >3 hours of hard physical activity per week. Light physical activity was defined as activity that does not involve sweating or a feeling of breathlessness. Mental distress was measured with the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-10 (HSCL-10), which has displayed high psychometric qualities in population-based studies.29 It mainly covers symptoms of depression and anxiety during last week, and comprises 10 items scored on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). When one or two items were missing, they were substituted with the sample mean value for corresponding items. If three or more items were missing, mental distress was classified as missing. Mental distress was assessed by the mean score with cut off at mean score ≥1.85.29

All measurements were performed according to a standard protocol and categorized in accordance with clinical guidelines.23,30–32 Body weight in kilograms and height in centimeters were recorded electronically with the participants wearing light clothes without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. BMI <25.0 was classified as normal/underweight, BMI ≥25.0 to <30.0 as overweight, and BMI ≥30.0 as obesity. Waist and hip circumference were measured horizontally with a steel cord to the nearest centimeter. Waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus. In obese participants it was set at the midpoint between the iliac crest and lower rib margin. Hip circumference was defined as the greatest circumference around the buttocks. Abdominal obesity was defined as waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85.30 Systolic and diastolic blood pressures (mm Hg) were measured by an automatic oscillometric device (DINAMAP, Criticon). After 2 minutes rest, three recordings were made at 1-minute intervals. The average of the second and third measurements was used in the analysis. Blood pressure was classified as normal (<130 mm Hg systolic and <85 mm Hg diastolic), high normal (130–139 mm Hg systolic or 85–89 mm Hg diastolic), and hypertension (≥140 mm Hg systolic or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic). The Department of Clinical Chemistry at Ullevål University Hospital in Oslo performed all laboratory investigations. Nonfasting serum blood lipids were measured directly by an enzymatic method (Hitachi 917 autoanalyzer, Roche Diagnostic) with internal quality control for every 30th sample. Serum total cholesterol was categorized as high (>6.20 mmol/L), borderline high (5.20–6.20 mmol/L), and recommended (<5.20 mmol/L); HDL cholesterol as low (<1.30 mmol/L), borderline low (1.30–1.50 mmol/L), and recommended (>1.50 mmol/L); triglycerides as high (>2.30 mmol/L), borderline high (1.70–2.30 mmol/L), and recommended (<1.70 mmol/L). Although fasting triglycerides often are preferred, it has been shown that nonfasting values might be an even better predictor of CVD in women.33

Statistical analysis

We conducted cross-sectional bivariate analyses to compare characteristics of women by lifetime experiences of IPV grouped into physical and/or sexual IPV, psychological IPV alone, and no IPV. Statistical significance was determined using Pearson chi-square test; however, Fisher exact test was preferred for diabetes because of low expected events. The comparison of clinical characteristics between groups was adjusted for age using direct standardization based on the age distribution of the entire study sample (Table 1). For prospective analyses we used Cox proportional hazards models to examine cardiovascular drug prescription by former IPV experiences. Separate analyses were conducted for antihypertensive and lipid-modifying drugs. Person-time was measured in months from the establishment of NorPD on January 1, 2004. Follow-up ended at the first redeemed prescription of any cardiovascular, antihypertensive, or lipid-modifying drugs respectively within the investigated time period. Otherwise observations were censored when a participant died, emigrated or by December 31, 2009. We used multivariate models with a priori defined covariates to investigate to what extent treatment initiation correlated with cardiovascular risk profile at baseline. Prescription of cardiovascular drugs overall were adjusted for education and Framingham risk score; antihypertensive drugs for age, education, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure; and lipid-modifying drugs for age, education, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. Age and education were categorical variables; all others were continuous. The tests were based on a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and restricted to women with complete data on included variables. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 19 (IBM).

Table 1.

Age Standardized Clinical Measurements and Cardiovascular Risk by Lifetime Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence at Baseline, 2000–2001

| |

No IPV (n=4842) |

Psychological IPV alone (n=336) |

Physical/sexual IPV (n=415) |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | p valuea |

| Body mass index, n=5577 | 0.703 | ||||||

| Normal/underweight (<25.0) | 2929 | (60.7) | 209 | (62.2) | 239 | (58.0) | |

| Overweight (≥25.0 and<30.0) | 1374 | (28.5) | 88 | (26.2) | 127 | (30.8) | |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 526 | (10.9) | 39 | (11.6) | 46 | (11.2) | |

| Abdominal obesity,bn=5593 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 739 | (15.3) | 46 | (13.7) | 92 | (22.2) | |

| No | 4103 | (84.7) | 290 | (86.3) | 323 | (77.8) | |

| Total cholesterol, n=5588 | 0.575 | ||||||

| High (>6.20 mmol/L) | 1004 | (20.7) | 71 | (21.2) | 78 | (18.9) | |

| Borderline high (5.20–6.20 mmol/L) | 1540 | (31.8) | 101 | (30.1) | 146 | (35.4) | |

| Recommended (<5.20 mmol/L) | 2296 | (47.4) | 163 | (48.7) | 189 | (45.8) | |

| HDL cholesterol, n=5586 | 0.031 | ||||||

| Low (<1.30 mmol/L) | 921 | (19.0) | 68 | (20.3) | 97 | (23.5) | |

| Borderline low (1.30–1.50 mmol/L) | 946 | (19.5) | 68 | (20.3) | 95 | (23.1) | |

| Recommended (>1.50 mmol/L) | 2972 | (61.4) | 199 | (59.4) | 220 | (53.4) | |

| Triglycerides, n=5589 | 0.003 | ||||||

| High (>2.30 mmol/L) | 308 | (6.4) | 29 | (8.7) | 42 | (10.1) | |

| Borderline high (1.70-2.30 mmol/L) | 453 | (9.4) | 38 | (11.3) | 49 | (11.8) | |

| Recommended (<1.70 mmol/L) | 4079 | (84.3) | 268 | (80.0) | 323 | (78.0) | |

| Blood pressure,cn=5589 | 0.519 | ||||||

| Hypertension | 713 | (14.7) | 46 | (13.7) | 56 | (13.5) | |

| High normal | 705 | (14.6) | 41 | (12.2) | 54 | (13.0) | |

| Normal | 3420 | (70.7) | 249 | (74.1) | 305 | (73.5) | |

| 10-year estimated risk of CVD,dn=5406 | 0.033 | ||||||

| 1st quartile (≤1.35%) | 1201 | (25.6) | 72 | (22.2) | 78 | (19.7) | |

| 2nd quartile (1.35%–2.25%) | 1181 | (25.2) | 71 | (21.9) | 99 | (25.0) | |

| 3rd quartile (2.25%–5.54%) | 1146 | (24.5) | 97 | (29.9) | 110 | (27.8) | |

| 4th quartile (>5.54%) | 1158 | (24.7) | 84 | (25.9) | 109 | (27.5) | |

Test of equality across the three categories of IPV exposure.

Waist-to-hip ratio≥0.85.

Hypertension: ≥140 mm Hg systolic or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic; high normal: 130–139 mm Hg systolic or 85–89 mm Hg diastolic; normal: <130 mm Hg systolic and <85 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure.

Based on Framingham risk stratification.

IPV, intimate partner violence; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Results

Altogether 751 (13.4%) of 5593 women disclosed lifetime experiences of any type of IPV; 645 (11.5%) reported psychological IPV, 339 (6.1%) physical IPV, and 172 (3.1%) sexual IPV (Fig. 2). Overall 415 (7.4%) women disclosed physical and/or sexual IPV, of whom 309 (74.5%) also reported psychological IPV, while 336 (6.0%) women reported psychological IPV alone.

Table 2 shows women's characteristics by lifetime experiences of IPV at baseline. Women who disclosed physical and/or sexual IPV or psychological IPV alone were more likely middle aged, divorced/separated, current smokers, and more frequently reported high levels of mental distress. In addition, women who disclosed physical and/or sexual IPV were more often unemployed and less educated; they were more likely to have ≥3 children and to report frequent alcohol use. There were no significant differences in physical activity, diabetes, or CVD in family according to IPV experiences.

Table 2.

Women's Characteristics by Lifetime Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence, 2000–2001

| |

No IPV (n=4842) |

Psychological IPV alone (n=336) |

Physical/sexual IPV (n=415) |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | p valuea |

| Age, n=5593 | <0.001 | ||||||

| 30 years | 1509 | (31.2) | 91 | (27.1) | 80 | (19.3) | |

| 40 and 45 years | 2158 | (44.6) | 180 | (53.6) | 250 | (60.2) | |

| 59 and 60 years | 1175 | (24.3) | 65 | (19.3) | 85 | (20.5) | |

| Education level, n=5551 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less than upper secondary | 590 | (12.3) | 56 | (16.8) | 79 | (19.2) | |

| Upper secondary | 1428 | (29.7) | 96 | (28.8) | 156 | (37.9) | |

| College/university | 2788 | (58.0) | 181 | (54.4) | 177 | (43.0) | |

| Paid employment, n=5547 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 4137 | (86.1) | 285 | (85.6) | 319 | (77.6) | |

| No | 666 | (13.9) | 48 | (14.4) | 92 | (22.4) | |

| Marital status, n=5592 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1803 | (37.2) | 122 | (36.4) | 122 | (29.4) | |

| Married | 2342 | (48.4) | 82 | (24.5) | 130 | (31.3) | |

| Divorced/separated | 561 | (11.6) | 126 | (37.6) | 156 | (37.6) | |

| Widowed | 136 | (2.8) | 5 | (1.5) | 7 | (1.7) | |

| Parity, n=5474 | <0.001 | ||||||

| None | 1614 | (34.1) | 96 | (29.0) | 106 | (26.0) | |

| 1 child | 906 | (19.1) | 81 | (24.5) | 76 | (18.7) | |

| 2 children | 1481 | (31.3) | 106 | (32.0) | 130 | (31.9) | |

| ≥3 children | 735 | (15.5) | 48 | (14.5) | 95 | (23.3) | |

| Daily smoking, n=5547 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Current | 1228 | (25.6) | 146 | (43.6) | 193 | (46.6) | |

| Former | 1256 | (26.2) | 81 | (24.2) | 119 | (28.7) | |

| Never | 2314 | (48.2) | 108 | (32.2) | 102 | (24.6) | |

| Alcohol use, n=5562 | 0.014 | ||||||

| 4–7 times a week | 236 | (4.9) | 21 | (6.3) | 33 | (8.0) | |

| <4 times a week | 4231 | (87.9) | 300 | (89.6) | 350 | (84.3) | |

| No use last year | 345 | (7.2) | 14 | (4.2) | 32 | (7.7) | |

| Physical activity, n=5561 | 0.299 | ||||||

| Inactive | 1412 | (29.3) | 98 | (29.5) | 142 | (34.4) | |

| Moderately active | 2786 | (57.8) | 189 | (56.9) | 223 | (54.0) | |

| Physically active | 618 | (12.8) | 45 | (13.6) | 48 | (11.6) | |

| Diabetes, n=5456 | 0.213 | ||||||

| Yes | 41 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.9) | 7 | (1.8) | |

| No | 4690 | (99.1) | 324 | (99.1) | 391 | (98.2) | |

| Cardiovascular disease in family, n=5035 | 0.225 | ||||||

| Yes | 1108 | (25.5) | 84 | (27.4) | 110 | (29.3) | |

| No | 3244 | (74.5) | 223 | (72.6) | 266 | (70.7) | |

| Mental distress, n=5355 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 448 | (9.7) | 60 | (18.9) | 99 | (24.8) | |

| No | 4191 | (90.3) | 257 | (81.1) | 300 | (75.2) | |

Test of equality across the three categories of IPV experiences.

Table 1 presents age-standardized values from clinical measurements and cardiovascular risk score by IPV. Women who had experienced physical and/or sexual violence were more likely to have abdominal obesity, low HDL cholesterol, elevated triglycerides, and slightly higher 10-year estimated risk of CVD than women who did not report IPV. There were no significant differences in BMI, total cholesterol, blood pressure, or self-reported diabetes.

Age-adjusted analyses showed that women who had experienced physical and/or sexual IPV were more likely to receive antihypertensive drug treatment than women who did not report IPV (Table 3). The association was not weakened by additional adjustments for education and systolic and diastolic blood pressure at baseline. There were no significant differences with respect to IPV and cardiovascular drugs overall or lipid-modifying drugs.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Lifetime Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Cardiovascular Drug Therapy, 2004–2009

| |

Age-adjusted |

Multivariable-adjusteda |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Person-years | Events | IRR | (95 % CI) | Women | Person-years | Events | IRR | (95 % CI) | |

| Cardiovascular drug use overall | ||||||||||

| No IPV (ref.) | 4842 | 24,858 | 1099 | 1 | — | 4652 | 23,939 | 1041 | 1 | — |

| Psychological IPV alone | 336 | 1714 | 84 | 1.15 | (0.92–1.43) | 322 | 1650 | 80 | 1.07 | (0.85–1.34) |

| Sexual/physical IPV | 415 | 2075 | 111 | 1.16 | (0.95–1.41) | 393 | 1965 | 104 | 1.08 | (0.88–1.33) |

| Antihypertensive drug use | ||||||||||

| No IPV (ref.) | 4842 | 25,897 | 798 | 1 | — | 4802 | 25,677 | 791 | 1 | — |

| Psychological IPV alone | 336 | 1796 | 60 | 1.11 | (0.85–1.45) | 333 | 1780 | 59 | 1.17 | (0.90–1.53) |

| Sexual/physical IPV | 415 | 2145 | 88 | 1.27 | (1.02–1.58) | 412 | 2127 | 88 | 1.36 | (1.09–1.70) |

| Lipid-modifying drug use | ||||||||||

| No IPV (ref.) | 4842 | 27,431 | 434 | 1 | — | 4804 | 27,212 | 431 | 1 | — |

| Psychological IPV alone | 336 | 1880 | 36 | 1.30 | (0.92–1.83) | 332 | 1860 | 35 | 1.22 | (0.85–1.74) |

| Sexual/physical IPV | 415 | 2345 | 34 | 0.89 | (0.63–1.27) | 410 | 2321 | 33 | 0.84 | (0.59–1.19) |

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) and confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for age, education, and clinical variables (cardiovascular drugs overall: adjusted for Framingham risk estimate; antihypertensive drugs: adjusted for systolic and diastolic blood pressure; lipid-modifying drugs: adjusted for total and HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides).

Discussion

In this population-based study, women with lifetime experiences of physical and/or sexual IPV were more likely to present several risk factors for CVD, including smoking, abdominal obesity, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides than other women. The prospective analysis documented that they were at increased risk of being treated with antihypertensive drugs. Thus, our findings substantiate the hypothesis of a potential link between IPV and CVD.

The study has several strengths and limitations. A major strength was the use of objective and accurate health measures from standardized clinical examinations and prospective drug information from a national prescription database. Further, the large sample-size and population-based design endorse generalizability of our findings. On the other hand, the prevalence of IPV in our study may have been underestimated for several reasons. The participation rate in HUBRO was low, and women who had low socioeconomic status, were unmarried, had non-Western origin, or received disability pension were underrepresented.22 Hence IPV may have been more prevalent among nonparticipants because IPV was associated with low socioeconomic status and poor health in this and other studies.2,4 Women subjected to IPV may also have been less willing to participate due to fear of retaliation from an abusive partner. Furthermore, our prevalence estimates were lower compared to a Norwegian national IPV survey that applied a more comprehensive violence questionnaire.2 Although nonparticipation may have biased our prevalence estimates, a study of the potential impact of selection by sociodemographic background in HUBRO yielded robust estimates for health-related variables, including smoking, BMI, and mental distress.22 Certain aspects may still have biased our associations, most likely toward zero. First, our association estimates might have been affected by differential selection bias if the severity of IPV influenced the probability of participation. Some studies suggest that severely abused women are less likely to participate in surveys compared with women who report lower levels of violence.34–36 If so, associations would be attenuated. Second, our study was conducted as part of a large public health survey that assessed IPV with five aggregate questions. Information about IPV severity and frequency was lacking, and disclosure of violence partly depended on women's own definitions of physical and sexual abuse. Since women subjected to IPV do not necessarily label violent acts as abuse, they may have been misclassified as not abused.37,38 In addition, some women in the control group may have experienced IPV during follow-up. Potential misclassification may have consecutively induced null findings. Yet it has been shown that aggregate questions on self-defined abuse have higher sensitivity for severe than for moderate violence.37,38 This might have influenced the associations in the opposite direction. Third, our study included only women without CVD or cardiovascular drug use at baseline in order to obtain a prospective study design and establish a temporal relationship between IPV and cardiovascular drug prescription.39 A supplementary analysis of excluded women revealed that physical and/or sexual IPV was significantly associated with angina pectoris at baseline (data not shown). This may have been an overexclusion, since IPV typically commence at younger age than CVD or cardiovascular drug use.9,40 Finally, prescription data were unavailable between 2001 and 2004 when HUBRO was conducted and NorPD was established, respectively.

The cross-sectional analyses showed that physical and/or sexual IPV was associated with several metabolic risk factors, including abdominal obesity, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides. Together with hypertension and raised fasting glucose, they are components of the metabolic syndrome, which is an important risk factor for type 2 diabetes and CVD.41 Prior data on IPV and metabolic syndrome are lacking. Yet it has been hypothesized that IPV may induce immune dysfunction and chronic inflammation that will eventually increase the risk of metabolic syndrome.11 Psychological factors including depression and anxiety are common sequelae of IPV as well as risk factors for CVD, and they have additionally been proposed as potential mediators of this inflammatory response.5,11,42 Women who reported IPV more often than others reported high levels of mental distress.29 Notwithstanding, it was beyond our objectives to explore a potential link between IPV, mental distress, and CVD. We had no information about inflammation or fasting blood glucose and were therefore unable to further explore a relationship between IPV and metabolic syndrome.

IPV was not associated with hypertension or total cholesterol in the current analysis, in contrast to former studies based on self-reports.15,43 Clinical information obtained by self-reports may, however, be inaccurate and hampered by detection bias, since health service utilization and likelihood of being diagnosed may differ by IPV experiences. Our study confirmed former findings of an increased probability of smoking in women who had experienced any type of IPV. Although BMI was not associated with IPV, women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV were more frequently abdominally obese. Actually, abdominal obesity has been found to be the strongest anthropometric predictor of cardiovascular death.44 It has been suggested that smoking and unhealthy eating habits could be adverse coping strategies to reduce IPV-induced stress or self-destructive behaviors as part of a depression among abused women.10,12,45 They might therefore benefit from health care that integrates interventions to end violence, relieve mental distress, and promote healthy lifestyle.

Women who disclosed IPV had slightly higher Framingham 10-year estimated risk of CVD. This risk assessment tool may help primary care physicians to identify women at high risk for CVD with measurements readily available at their office.28 Yet it does not incorporate metabolic risk factors such as abdominal obesity, indications of insulin resistance, or triglycerides. Our findings indicate that health care providers should assess CVD risk including metabolic risk factors in their follow-up of women who have experienced IPV.

Smoking and mental distress were more common in women who reported psychological IPV alone than women without IPV experiences; otherwise, their risk profile appeared similar with respect to cardiovascular risk factors such as abdominal obesity, blood lipids, and cardiovascular drug use. Our findings suggest that it is particularly IPV comprising physical and/or sexual violence that is associated with increased cardiovascular risk. This is consistent with results from a study of help-seeking individuals, in which physical and/or sexual IPV, but not psychological IPV alone, was associated with angina pectoris and CVD.21 Yet a recent study found an association between severe emotional IPV and hypertension.43 However, it was not reported whether or not women also had experienced physical or sexual IPV. Our results should not be interpreted as psychological IPV being less severe than physical or sexual IPV. The unequal health impact of physical and/or sexual IPV and psychological IPV alone in our study may stem from a cumulative effect because most women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV had experienced several types of violence, including psychological abuse (Fig. 2). It may also relate to the fact that they more frequently were unemployed and less educated, since low socioeconomic status is associated with poor cardiovascular health.46

The prospective analysis documented that women who reported physical and/or sexual IPV were more likely to be prescribed antihypertensive drugs than women without IPV experiences. CVD is a principal cause of morbidity worldwide, and cardiovascular drug use is frequently used both as primary and secondary prophylaxis.8,9 Prescription of cardiovascular drugs in our study probably indicates that a physician identified CVD or elevated cardiovascular risk in a woman during follow-up. When we adjusted for age, education, and blood pressure levels at baseline, the association was even slightly strengthened. In comparison, no significant differences were found with respect to cardiovascular drugs overall or lipid-modifying drugs. This was somewhat unexpected because physical and/or sexual IPV was associated with dyslipidemia, including low HDL cholesterol and elevated triglycerides at baseline. Since drug prescription fundamentally relies on a patient's medical diagnosis, it is strongly influenced by factors such as access to health services and the physician's assessment. We did not have information about women's medical follow-up and were unable to examine whether their risk factors were identified in health care. The context of drug prescription should be investigated in future research. Our study was undertaken in an urban population in a country with universal health care coverage, where access to prescription drugs is intended not to depend on personal economy. Many women were also relatively young with respect to CVD, which typically occurs in older age. Similar investigations should be performed in other settings, and include more women in older age groups.

This study provided new evidence of a link between IPV and several cardiovascular risk factors. Future studies should investigate the mechanisms behind this link in order to develop adequate preventive measures.

Conclusions

We conclude that women who have experienced IPV may be an important target population for primary prevention of CVD. Physical and/or sexual IPV was associated with increased levels of several metabolic risk factors for CVD. Furthermore, smoking was more common in women who had experienced any type of IPV. Over time, women who had experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner were more likely to be prescribed antihypertensive drugs. Clinicians should assess the cardiovascular risk of women who have experienced IPV and address the need to modify risk factors for CVD in their follow-up. Early detection of risk factors may in fact reduce their risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

The data collection was conducted as part of the Oslo Health Study 2000–2001 and linked with records from the Norwegian Prescription Database in collaboration with the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. We thank all respondents for participating. This study was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (grant number 185755/V50).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Saltzman LE. Fanslow JL. McMahon PM. Shelley GA. Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neroien AI. Schei B. Partner violence and health: Results from the first national study on violence against women in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:161–168. doi: 10.1177/1403494807085188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krug EG. Mercy JA. Dahlberg LL. Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Moreno C. Jansen HA. Ellsberg M. Heise L. Watts CH WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos T. Astbury J. Piers LS, et al. Measuring the impact of intimate partner violence on the health of women in Victoria, Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:739–744. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Moreno C. Watts C. Violence against women: an urgent public health priority. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.085217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendis S. Puska P. Norrving B. Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: guidelines for assessment and management of total cardiovascular risk. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott-Storey K. Wuest J. Ford-Gilboe M. Intimate partner violence and cardiovascular risk: is there a link? J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:2186–2197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall-Tackett KA. Inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome as sequelae of violence against women: the role of depression, hostility, and sleep disturbance. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:117–126. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshihama M. Horrocks J. Bybee D. Intimate partner violence and initiation of smoking and drinking: a population-based study of women in Yokohama, Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jun HJ. Rich-Edwards JW. Boynton-Jarrett R. Wright RJ. Intimate partner violence and cigarette smoking: association between smoking risk and psychological abuse with and without co-occurrence of physical and sexual abuse. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:527–535. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonomi AE. Anderson ML. Reid RJ. Rivara FP. Carrell D. Thompson RS. Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1692–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breiding MJ. Black MC. Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence-18 U.S. states/territories, 2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dichter ME. Cerulli C. Bossarte RM. Intimate partner violence victimization among women veterans and associated heart health risks. Womens Health Issues. 21:S190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshihama M. Horrocks J. Kamano S. The role of emotional abuse in intimate partner violence and health among women in Yokohama, Japan. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:647–653. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.118976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stene LE. Dyb G. Tverdal A. Jacobsen GW. Schei B. Intimate partner violence and prescription of potentially addictive drugs: prospective cohort study of women in the Oslo Health Study. BMJ Open. 2:e000614. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stene LE. Dyb G. Jacobsen GW. Schei B. Psychotropic drug use among women exposed to intimate partner violence: a population-based study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:88–95. doi: 10.1177/1403494810382815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludermir AB. Lewis G. Valongueiro SA. de Araujo TV. Araya R. Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 376:903–910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coker AL. Davis KE. Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Søgaard AJ. Selmer R. Bjertness E. Thelle D. The Oslo Health Study: the impact of self-selection in a large, population-based survey. Int J Equity Health. 2004;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Søgaard AJ. Selmer R. The Oslo Health Study. www.fhi.no/dav/bbb2a86ad7.doc. [Feb 29;2012 ]. www.fhi.no/dav/bbb2a86ad7.doc

- 24.Furu K. Establishment of the nationwide Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD)—new opportunities for research in pharmacoepidemiology in Norway. Nor J Epidemiol. 2008;18:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swahnberg IM. Wijma B. The NorVold Abuse Questionnaire (NorAQ): validation of new measures of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and abuse in the health care system among women. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13:361–366. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilpatrick DG. What is violence against women: defining and measuring the problem. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19:1209–1234. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Agostino RB., Sr Vasan RS. Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strand BH. Dalgard OS. Tambs K. Rognerud M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: A comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36) Nord J Psychiatr. 2003;57:113–118. doi: 10.1080/08039480310000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio. Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, December 8–11, 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chalmers J. MacMahon S. Mancia G, et al. 1999 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the World Health Organization. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1999;21:1009–1060. doi: 10.3109/10641969909061028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bansal S. Buring JE. Rifai N. Mora S. Sacks FM. Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2007;298:309–316. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waltermaurer EM. Ortega CA. McNutt LA. Issues in estimating the prevalence of intimate partner violence: assessing the impact of abuse status on participation bias. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18:959–974. doi: 10.1177/0886260503255283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNutt LA. Lee R. Intimate partner violence prevalence estimation using telephone surveys: understanding the effect of nonresponse bias. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:438–441. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson MP. Conflict and control: gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1003–1018. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellsberg M. Heise L. Pena R. Agurto S. Winkvist A. Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamby SL. Gray-Little B. Labeling partner violence: when do victims differentiate among acts? Violence Vict. 2000;15:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:54–60. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivara FP. Anderson ML. Fishman P, et al. Age, period, and cohort effects on intimate partner violence. Violence Vict. 2009;24:627–638. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alberti KG. Eckel RH. Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wulsin LR. Singal BM. Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:201–210. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058371.50240.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mason SM. Wright RJ. Hibert EN. Spiegelman D. Forman JP. Rich-Edwards JW. Intimate partner violence and incidence of hypertension in women. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petursson H. Sigurdsson JA. Bengtsson C. Nilsen TI. Getz L. Body configuration as a predictor of mortality: comparison of five anthropometric measures in a 12 year follow-up of the Norwegian HUNT 2 study. PLoS One. 6:e26621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNutt LA. Carlson BE. Persaud M. Postmus J. Cumulative abuse experiences, physical health and health behaviors. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaplan GA. Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation. 1993;88:1973–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]