Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine predictions derived from the Lexical Quality Hypothesis (Perfetti & Hart, 2002; Perfetti, 2007) regarding relations among word-decoding, working-memory capacity, and the ability to integrate new concepts into a developing discourse representation. Hierarchical Linear Modeling was used to quantify the effects of two text properties (length and number of new concepts) on reading times of focal and spillover sentences, with variance in those effects estimated as a function of individual difference factors (decoding, vocabulary, print exposure, and working-memory capacity). The analysis revealed complex, cross-level interactions that complement the Lexical Quality Hypothesis.

Text comprehension requires that readers decode symbols from a written orthography, map those symbols onto representations in a mental lexicon, derive meanings of individual words, and integrate those meanings with one another on the basis of syntactic information and background knowledge. For skilled readers, these processes are usually automatic and effortless, but the apparent simplicity of the reading experience belies an extremely complex cognitive ability that relies on a multitude of skills for its execution. As a consequence, individuals vary considerably in their ability to learn and execute this skill, resulting in large individual differences in reading ability even among college students (e.g., Bell & Perfetti, 1994).

Our goal in this study was to examine individual differences in text comprehension by focusing on the influence of word recognition skill on the execution of high-level integration processes. Our study has its foundation in a theory of variation in text comprehension called the Lexical Quality Hypothesis (Perfetti & Hart, 2002; Perfetti, 2007). According to the theory, higher-order comprehension processes such as sentence integration and inference generation rely on efficient and accurate lexical access that is granted by high-quality lexical codes. The quality of a lexical code is determined by the degree to which it has orthographic, phonological, and semantic specificity, allowing a word to be processed and understood coherently when it is encountered in both visual and auditory modalities (Perfetti, 1985). Coherence refers to the idea that these word features are accessed in synchrony, resulting in a unitary word perception event (Perfetti & Hart, 2002). Perfetti and his colleagues argue that multiple encounters with a word produce a common ‘core representation’ that provides a nexus among its orthographic, phonological, and semantic features. The theory implicates word-decoding ability, reading experience, and vocabulary, as integral to reading proficiency.

Inferior lexical codes may affect reading comprehension in three ways. First, the comprehension processes that are needed to construct discourse representations at the situation level (e.g., knowledge-based inferences) will be impeded by lexical representations that are semantically impoverished. That is, poorly understood words will activate an inadequate collection of concepts, impairing the generation of knowledge-based inferences. Second, improperly specified words will activate context-inappropriate words that share orthographic, phonological, or semantic features with the encountered word’s form, resulting in interference and increased ambiguity effects (e.g., Perfetti & Hart, 2001). Third, resources that would normally be dedicated to higher-order comprehension processes (such as inference generation or sentence integration) will be monopolized by effortful lexical processing.

In this study, we examined one of the central tenets of the Lexical Quality Hypothesis; that poor word recognition ability impairs comprehension processes that operate at sentence- and discourse- levels. In children, decoding skill plays a central role in word recognition by allowing new and unfamiliar letter strings to be deciphered and encoded. With exposure and practice, however, reading becomes an automated, orthographically-based system driven more by recognition and analogy than by analysis of phonology (e.g., Ehri, 1995; Frith, 1985). As such, the impact of decoding ability on comprehension processes in adult readers is deemed important only for those who have failed to achieve fluency. Relatively few studies, however, have examined the relation between word-decoding and comprehension in skilled adult readers.

Bell and Perfetti (1994) took a sample of university students (n = 29) and placed them into three groups on the basis of performance on the Nelson-Denny reading test, SAT scores (verbal and quantitative), and a spatial ability test. The high-skill group scored well on all of the measures, and the two low-skill groups comprised one that scored more poorly than the high skill group on all of the measures, and another that scored equally well on the non-verbal measures but poorly on the verbal measures. When they collapsed across this diverse sample of college students, Bell and Perfetti found that performance on pseudoword naming tasks (pronouncing nonword letter strings such as ‘choyce’) predicted a significant proportion of variance in comprehension test scores for science texts (R2 = 10.6%), but not for history (R2 = 0.3%), or narrative texts (R2 = 3.4%). This result led them to propose that decoding affects comprehension when readers encounter the new and unfamiliar words that are typical of more technical texts. Similarly, Braze, Tarbor, Shankweiler, and Mencl (2007) investigated component reading skills in a group of adolescent and young adults (n = 47) obtained from adult education centers serving urban neighborhoods. These ‘non-college bound’ readers had full-scale IQs of 80 or more and were able to read aloud 70% of attempted items from the fast reading subtest of the Stanford Diagnostic Reading test (Karlsen & Gardner, 1995). Braze et al. demonstrated that pseudoword naming accounted for a significant proportion of variance in reading comprehension (R2= 18%), but that this contribution dropped substantially after accounting for the effects of oral vocabulary (<6%). Similarly, in a large sample (n = 928) of college students with no diagnosed reading or learning disabilities, Landi (2010) demonstrated that pseudohomophone detection accounted for less than 1% of the variance in performance on the comprehension component of the Nelson Denny reading test once the contributions of vocabulary and print exposure had been controlled.

The available evidence seems to suggest that decoding processes are not a limiting factor in comprehension for skilled readers. This conclusion may be premature, however, for two reasons. First, the relation between word-decoding and comprehension has been investigated in the context of standardized reading comprehension tests, such as the Nelson-Denny (e.g., Braze et al., 2007; Landi, 2010). Standardized reading tests, especially those that allow readers to answer questions as they peruse the passages, may not be very sensitive to the influence of decoding on comprehension in adults because its influence may be masked by higher-level processes. To our knowledge, only one study has examined the influence of word-decoding on reading comprehension on-line, as readers are developing their discourse representation. Lundquist (2003) found that adult readers who performed poorly on a decoding measure read connected text more slowly than did readers who performed well on the measure, although the two groups did not differ on overall comprehension of the text. Second, word-decoding ability may interact with working-memory capacity to influence comprehension ability. Sluggish word-decoding processes are presumed to consume cognitive resources that would otherwise be devoted to high-level integration processes (e.g., Perfetti, 1985). Therefore, word-decoding may be a limiting factor in comprehension primarily in low-capacity readers; those readers who lack the resources necessary to compensate for resource-consuming word recognition processes.

For the most part, evidence for a link between word-level skills and the ability to execute high-level, on-line integration processes has been indirect, relying on the well-established correlation between word-recognition skill and reading comprehension ability. Perfetti, Yang, and Schmalhofer (2008) reported two studies (Yang et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2007) in which college-age readers were classified as good or poor comprehenders on the basis of their performance on the Nelson Denny reading test. Across the two studies, the groups showed differences in the magnitude and time-course of event-related brain potentials (ERPs) that were elicited by manipulations at the discourse level. In Yang et al., (2005), poor comprehenders showed larger N400 deflections, an index of semantic integration difficulty, to noun phrases related to a preceding sentence inferentially (e.g., the bomb hit the ground. The explosion …). These less skilled readers also showed extended latencies in their P300 deflections, indicative of recognition-memory processes, elicited by paraphrased expressions (e.g., the bomb…blew-up. The explosion…). These effects were taken as evidence for effortful and ‘sluggish’ word-to-text integration processes in the poor comprehenders. The authors proposed that these processing differences may be attributable to local integration processes that occur at the word level, including the ability to use context- dependent word meanings (Perfetti et al., 2008). It is important to note, however, that this interpretation is based on the assumption that the poor comprehenders had deficient word recognition or integration abilities: Although neural responses to discourse-level manipulations differed between the two groups of readers, no direct measures of word-level skill or cognitive processes such as decoding, vocabulary, or working-memory capacity, were included in either study. Ashby, Rayner, and Clifton (2005) compared the eye movement records of highly skilled and average readers to determine whether they were differentially affected by word frequency and predictability. They presented high- and low- frequency words in non-constraining sentence contexts (e.g., ‘the runners will now stand at the starting blocks; ‘over time, the dog became as timid as its owner’). Both groups of readers read low-frequency words more slowly than high-frequency words, consistent with previous findings in the literature. However, average readers spent longer fixating the low-frequency words than skilled readers, suggesting that both groups of readers completed lexical access before their eyes moved from the target word, but that this was slower for the average readers. In a second study, they manipulated word frequency and predictability; high- and low- frequency target words were embedded in high-constraint or low-constraint contexts (e.g., high-frequency predictable/low frequency unpredictable: ‘most cowboys know how to ride a horse/camel if necessary’; low-frequency predictable/high frequency unpredictable: ‘in the desert, many Arabs ride a camel/horse to get around’). The predictability manipulation affected the two groups quite differently. Skilled readers demonstrated frequency effects in both conditions such that, irrespective of predictability, high-frequency targets were read more quickly than low frequency targets. However, average readers demonstrated frequency effects only when the word was highly predictable. When the target word was not predicted by context, gaze durations on the target did not vary as a function of word frequency. Rather, the average readers’ short duration fixations were associated with a 26 msec frequency effect in spillover time, suggesting that these readers completed lexical access after their gaze had left the low-frequency unpredictable target (Ashby et al., 2005). This suggests that the average readers relied on context to a greater degree than did the skilled readers, potentially as a method by which subsequent words could be predicted.

Hersch and Andrews (2012) found similar effects when they investigated reading processes in a group of undergraduate university students. These authors submitted participants to a battery of individual difference measures in order to estimate their reading comprehension ability, reading speed, reading span, vocabulary, and spelling skill. The two measures of spelling ability, dictation and recognition, were administered in order to estimate the precision of participants’ lexical representations, with better performance indicating a higher degree of lexical quality. The participants then took a novel reading task (RSVP) in which target-distracter word pairs were presented before or after a supporting context. After reading the sentence, the subjects’ task was to report which of the two words fit best with the context given by the sentence as a whole. Unsurprisingly, readers with superior reading and spelling profiles showed greater accuracy in target word selection than poorer readers, irrespective of the position of the supporting context. However, exceptional spelling ability was associated with greater accuracy when the word-pairs were presented before the supporting context. Exceptional spellers were better able to identify words in the absence of supporting context, suggesting a reduced reliance on context that was granted by superior bottom-up (i.e., lexical) processing. In contrast, the poorer spellers relied on top-down, contextually-driven processes in order to aid the identification of incoming words.

In this study, we examined the influence of word-level skills and cognitive abilities to on-line comprehension processes in adult readers from a college population. We asked whether poor word recognition skills limit readers’ ability to execute high-level processes that are involved in integrating new information into a discourse representation. In particular, we focused on readers’ ability to integrate new-noun concepts into a discourse model, and examined the roles of word-level skills and working-memory capacity in the ability to integrate these new entities into an unfolding discourse-level representation.

When a noun in a sentence has no referent in the existing discourse model, readers must establish a new entity and integrate it into their representation of the text, a process that has been shown to be time-consuming. For example, Haberlandt and his colleagues (Haberlandt, Graesser, Schneider, & Kiely, 1986; Haberlandt, Graesser, & Schneider, 1989) investigated the integration of new-noun concepts (nouns that have not been mentioned in the preceding discourse) using a moving window procedure (Just, Carpenter, & Woolley, 1982). Regression analyses demonstrated that the number of new-noun concepts in a sentence predicted increases in sentence reading times, even when other lexical properties such as log-frequency, length, and serial position were controlled. These increases were more pronounced for words at boundary locations (i.e., clause and sentence boundaries) than for words at non-boundary locations (i.e., mid-sentence), suggesting that new-noun integration is an aspect of processes that are involved in sentence wrap-up. Importantly, the beta coefficients that represented the processing costs associated with integrating new-noun concepts were significantly correlated with recall performance (r = .51, p < .01), suggesting that the reading time increases reflected processes that served to facilitate comprehension. Similarly, Stine-Morrow, Noh, and Shake (2010) found a relation between new concept integration times and text memory, and revealed that this effect was amenable to strategic control. When young and elderly participants were instructed to consciously integrate the meanings of new entities with one another as they read, reading-time increases were more pronounced and text memory improved. Furthermore, integration effects varied with readers’ age such that elderly readers showed integration effects within sentences, as each new noun was encountered, and younger subjects showed integration effects at sentence boundaries. This difference was attributed to variation in processing capacity.

We examined the processing costs associated with integrating new-noun concepts into a developing discourse representation in light of predictions that were derived from the Lexical Quality Hypothesis. A large group of participants received tests to estimate their working-memory capacity, decoding ability, vocabulary, and reading experience. They then read a series of narrative texts using a sentence-by-sentence procedure. We modeled reading times for each sentence (sentence N) as a function of three properties: Word frequency, sentence length, and the number of new-noun concepts introduced in the sentence.

One of the central proposals of the Lexical Quality Hypothesis is that lexical access can be delayed (i.e., ‘sluggish’) in readers with poor word-level abilities. It is plausible, therefore, that the effects of sentence properties may spill-over into subsequent sentences. Thus, we also modeled reading times of each sentence as a function of the properties of the preceding sentence (sentence N-1). By using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) to model these effects simultaneously, we were able to quantify the specific relations between text properties and reader characteristics during on-line comprehension.

Our primary predictions concerned the relation between word-decoding and new-noun integration. First, we predicted that word-decoding should be related to the speed with which new-nouns are integrated. If poor word-decoding abilities consume resources that would otherwise be used to integrate ideas within and across sentences, then new-noun integration should be slowed. Second, we predicted that word-decoding and working-memory capacity may interact to influence the integration of new-noun concepts. If poor word-decoding impairs comprehension because it consumes resources that would otherwise be used to execute integration processes, then working-memory capacity may modulate the relation between word-decoding and new-noun integration. Thus, we predicted a 3-way, cross-level interaction between working-memory capacity, word-decoding, and new-noun concept integration time.

The Lexical Quality Hypothesis makes clear predictions with regard to how decoding ability and integration should be related, but its predictions with regard to the relation between word knowledge (vocabulary and print exposure) and new-noun integration are less clear. According to the hypothesis, word recognition for improperly specified words is ‘sluggish’, constraining comprehension by monopolizing resources and by activating context-inappropriate words that share orthographic, phonological, or semantic features with the encountered word’s form (e.g., Perfetti & Hart, 2001), and failing to activate context-appropriate concepts that may be used as the basis for inferences. As such, the effects of vocabulary and/or print exposure may be very similar to the predicted effects of decoding: Readers with poor vocabularies or low indices of print exposure may show slowed new-noun integration. Furthermore, if access to poorly specified lexical representations consumes cognitive resources that would otherwise be devoted to higher-order comprehension processes, then working-memory may modulate the relation between vocabulary/print exposure and new-noun integration.

Method

Participants

One hundred and thirteen undergraduates took part in the study in return for course credit. All were recruited from at the University of California at Davis subject pool, spoke English as their native language, and none had any diagnosed reading or learning disabilities. Full ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at UC Davis. The data were collected across two sessions. Twelve participants did not complete both sessions. The analyses presented below are based on data from 101 participants.

Materials

Five narrative texts ranging in length from 9 to 56 sentences were read in a self-paced reading paradigm (122 sentences, in total). We selected the texts to be short, full-length stories rather than story excerpts. In addition to being short in length, we selected texts that were heterogeneous with respect to story structure. Three of the texts were parodies of well-known fairytales and parables: The Little Girl and The Wolf (Thurber, 1983); The Shrike and The Chipmunks (Thurber, 1983); and The Moth and The Star (Thurber, 1983). The structures of these texts were deemed likely to be highly familiar to the adult readers, but their conclusions were atypical and often sardonic (e.g., “Early to rise and early to bed makes a man healthy and wealthy and dead.” Thurber, 1983). Two of the texts were longer and had more contemporary structures and themes: I am Bigfoot (Carlson, 2003) – the unapologetic confessions of a promiscuous Sasquatch; and Brilliant Silence (Holst, 2000) – a sentimental account of two polar bears’ escape from incarceration. Each sentence of each text was coded along three textual dimensions. First, each sentence was hand-coded for nouns that mentioned new entities, that is, nouns that had no referent in the preceding discourse. There were 236 instances of these new noun concepts, 12 of which repeated across two texts or more. Second, each sentence was coded for length in terms of number of syllables. Finally, each sentence was coded for average log-frequency (Kucera & Francis, 1967) of the words in the sentence. Example sentences, and their coding, are provided in Table 1. Mean sentence length was 22.11 syllables (SD: 15.53; Range: 1–101), the average number of new noun concepts per sentence was 1.93 (SD: 2.23; Range: 0 – 14), and the mean of the average log-frequency of the words in each sentence was 6.84 (SD: 2.50; Range 0.72 – 27).

Table 1.

Sentence coding examples.

| Text | Sentence | New Noun Concepts |

Length (syllables) |

Average Log-Frequency (K-F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Little Girl and The Wolf | “One afternoon a big wolf waited in a dark forest for a little girl to come along carrying a basket of food to her grandmother.” | 6 | 36 | 6.99 |

| The Shrike and The Chipmunks | “To be sure, the female chipmunk* had not been gone three nights before the male* had to dress for a banquet and could not find his studs or shirt or suspenders.” | 5 | 38 | 6.95 |

| The Moth and The Star | “A young and impressionable moth once set his heart on a certain star.” | 3 | 18 | 6.37 |

| I am Bigfoot | “Well, first of all, I don't live in the woods year round, which is a popular misconception of my life-style.” | 3 | 26 | 6.81 |

| Brilliant Silence | “On nights when the sky is bright and the moon is full, they* gather to dance.” | 3 | 17 | 7.49 |

Previously mentioned entities

Procedure

In session 1, participants completed the self-paced reading paradigm and the vocabulary component of the Nelson-Denny reading test (Brown, Fishco, & Hanna, 1993). In session two, participants completed the nonword naming task, both working-memory tests, the author recognition test, and the magazine recognition test.

Self-paced reading paradigm

Participants read each of the five narrative texts at their own pace, one sentence at a time. Texts were presented in random order. Participants were instructed to read each sentence, pressing the spacebar to move onto the next. When they had finished reading a text, they were asked 10 multiple-choice comprehension questions about it, each with 5 response options. These questions were designed to assess item-specific text memory, global theme extraction, and inference making. One of the computers did not record responses throughout the study, meaning that comprehension data were recorded for 87 subjects, only. Analyses including this variable are restricted to these participants.

We administered tests designed to measure several cognitive and linguistic abilities that are associated with comprehension skill: Word-decoding ability, working-memory capacity, vocabulary, and print exposure. All of these tasks were used in Long, Prat, Johns, Morris, and Jonathan (2008) and were administered in the same manner.

Word-decoding skill

Decoding ability was measured with a nonword naming task in which participants were required to pronounce nonword letter strings (e.g., tenvorse) as quickly and as clearly as possible. 100 nonwords ranging from 1 to 3 syllables (4 to 9 letters) were presented to subjects using Direct RT (Jarvis, 2008). A voice-key was used to record onset latencies, with longer latencies indicating poorer decoding skill. Accuracy in this task was high: Mean: 89.12; SD = 5.90; Range = 76 to 100.

Working-memory capacity

Working-memory capacity was measured with reading-span and operation-span tasks. The reading-span task (Daneman & Carpenter, 1980) was comprised of 60 sentences arranged as 15 trials in variable sets of 2, 3 4, 5, and 6 sentences. Sentence length ranged from 9 to 23 words. 50% of the sentences made sense, and 50% did not. Each sentence was presented on a computer screen (e.g., To Sylvia, the thought of coming home to a quiet house was pure luxury), and participants were asked to read the sentence aloud, to state whether it made sense or not, and to store the last word for later recall (e.g., luxury). Once all of the sentences in a set had been presented, participants were prompted to recall the sentence-final words from that set (2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 words, depending on the set size). As recommended by Freidman and Miyake (2005), set sizes were presented in random order, and each participant’s reading-span was taken as the total number of correctly recalled words over the entire test, irrespective of set size. Accuracy on the sentence comprehension portion of the task was high: Mean = 93.78; SD = 4.91; Range = 78 to 100).

The operation-span task (Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999) was comprised of 60 arithmetic problems in variable sets of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 problems. Each problem was presented alongside its solution and a to-be-remembered word (e.g., (8/2) − 4 = 4? PIANO). Participants were asked to read the problem and solution aloud, to state whether the solution was correct or incorrect, and to commit the adjacent word to memory. Once all of the problems in a set had been presented, participants were prompted to recall the words from that set. Again, set sizes ranged from 2 to 6 items and were presented in a random order, and each participant’s operation-span size was taken as the total number of correctly recalled words over the entire test. Accuracy on the arithmetic problems was high: Mean = 91.22; SD = 6.28; Range = 78 to 100).

Vocabulary

Vocabulary was measured with the vocabulary component of the Nelson-Denny Reading Test (Brown, Fishco, & Hanna, 1993). The test is comprised of 80 multiple choice items, each with 5 response options. The words are drawn from high school and college text books and vary in frequency and difficulty. Administration time for the test is 20 minutes. The internal consistency of the test is moderate to high, with Chronbach’s alpha estimated at .81 (Brown, Fishco, & Hanna, 1993).

Print exposure

Print exposure was estimated with the Author Recognition Test (ART) and the Magazine Recognition Test (MRT). These tests required participants to discriminate real authors and magazine titles from lists of foils (Stanovich & West, 1989). For the ART, 50 authors (80% fiction, 20% non-fiction) were drawn from a list of those who had appeared on the New York Times Best Seller List (2008) for at least 1 month. Fifty foils were created by drawing names from the editorial boards of Experimental Psychology journals, at random. For the MRT, 50 titles were drawn from Amazon’s best-selling magazine list (2008). Fifty foils were created by a group of undergraduate research assistants.

Results

The reading time (RT) data were Winsorized according to the following criteria. First, syllable-by-syllable RTs were calculated for each participant, and sentences whose mean RT per syllable was less than 50 msec were replaced with that value (15 data points; 0.1%). Mean RTs per syllable were then re-calculated for each participant. Sentence RTs that were greater than 2.5 SD above each subject’s mean for all sentences were replaced with that value. Three hundred and nineteen data points (2.59%) were replaced in this way. HLM 6 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2004) requires that no data are missing from any case for any participant, and engages in listwise case deletion to avoid such occurrences. Five hundred and thirty-two data points (4.31%) were deleted on this basis. The analyses presented below are based on 11786 data points. After this treatment, the mean RT for each sentence was 4,542ms (SD = 3,559; Range = 374 to 29,735).

For the eighty seven participants who completed the comprehension questions, accuracy was high across all question types. The mean proportion accuracy on questions tapping main ideas was .92 (SD = .18; Range = .18 to 1). The mean proportion accuracy on questions tapping details was .89 (SD = .12; Range = .12 to 1). Lastly, the mean proportion accuracy on questions tapping inferences was .85 (SD = .13; Range = .13 to 1).

Individual-Difference Measures

Many of the individual-difference measures were designed to measure similar cognitive and linguistic faculties. To determine which, if any, of these variables would be best represented as composites, the data were factor analyzed. The six reader skill variables were subjected to a principal components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (KMO = .60), and all KMO values for individual variables were larger than the requisite value of .50 (see Field, 2009). Bartlett’s test of sphericity, Χ2 (15) = 124.21, p < .001, demonstrated that correlations between the items were large enough for PCA. Two of six extracted components had eigenvalues above Kaiser’s criterion of 1, and together explained 60.75% of the variance (33.09% and 27.66%, respectively). Table 2 contains descriptive information about the individual-difference measures. Table 3 shows the factor loadings after rotation.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Reader Skill Measures (N = 101)

| Measure | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| ND Vocabulary (Percentile Rank) | 54.98 | 23.81 | 2 – 90 |

| Operation-Span (Total) | 31.57 | 4.39 | 19 – 40 |

| Operation Span (Accuracy %) | 91.22 | 6.28 | 76 – 100 |

| Reading-Span (Total) | 41.42 | 6.90 | 25 – 57 |

| Reading Span (Accuracy %) | 93.78 | 4.91 | 78 – 100 |

| Nonword Naming (Milliseconds) | 922.43 | 195.58 | 587 – 1667 |

| Nonword Naming (Accuracy %) | 89.12 | 5.90 | 76 – 100 |

| Author Recognition Test (Total Correct) | 11.04 | 5.28 | 0 – 30 |

| Magazine Recognition Test (Total Correct) | 24.50 | 6.78 | 7 – 39 |

| Experience/Vocabulary Composite | 30.26 | 10.08 | 5 – 49 |

| Working-Memory Composite | 24.50 | 5.08 | 23 – 48 |

Table 3.

Summary of Exploratory Factor Analysis for the Reader Skill Variables (N = 101)

| Rotated Factor Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Vocabulary/Experience | Working-Memory |

| Vocabulary | .755 | .211 |

| Operation-Span | .890 | |

| Reading-Span | .876 | |

| Nonword Naming | −.154 | −.195 |

| Author Recognition Test | .850 | .155 |

| Magazine Recognition Test | .811 | |

Three of the individual-difference variables loaded highly onto factor 1, a factor that appeared to describe vocabulary and reading experience. Vocabulary, ART, and MRT were summed and divided by 3 to form the composite measure, Vocabulary/Experience. The two measures of working-memory (operation-span and reading-span) loaded highly onto factor 2, suggesting that these variables measured the same construct. These scores were summed and divided by 2 to form the composite, Working-Memory. Lastly, nonword naming loaded onto both factors, but not highly enough to be considered meaningful. This measure was retained as a separate variable, Decoding. Table 4 depicts the Pearson’s r correlation coefficients among these variables and comprehension question accuracy.

Table 4.

Pearson’s r Correlation Coefficients for Composite Reader Measures and Comprehension Question Accuracy

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Working-Memory | - | |||||

| 2. Vocabulary/Experience | .18^ | - | ||||

| 3. Decoding (msec) | −.08 | −.13 | - | |||

| 4. Main Ideas | .32* | .27* | −.01 | - | ||

| 5. Details | .14 | .15 | −.19^ | .34** | - | |

| 6. Inferences | .13 | .08 | −.11 | .39** | .66** | - |

p </= .001;

p < .05;

p </= .09

HLM 6 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2004) was used to model the sentence reading times as a function of text- and reader- characteristics. All variables were grand-mean centered before analysis, and interaction terms’ constituents were grand mean centered prior to their construction. Level-one variables were entered into the model with all slopes and intercepts allowed to vary at random. Next, all of the individual-difference variables and their associated interaction terms were entered at the 2nd level of the model. The model was then backwards-built, with level-2 variables incrementally removed on the basis of their t-values (i.e., lowest values removed first). Variables were removed until all that remained were statistically significant predictors of variance in level-1 coefficients. Non-significant random effects were then fixed. The model that resulted from this procedure is as follows:

Level-1 Model

RTi(sentence) j(subject) = β0j + β1j (N lengthi) + β2j(N-1 lengthi) + β3j(N New-Noun Conceptsi) + β4j(N-1 New-Noun Conceptsi) + β5j (N log-frequencyi) + β6j (N-1 log-frequencyi) + εij

Level-2 Model

β0j = γ00 + γ01(Decodingj) + γ02(Vocabulary/Experiencej) + p0j

β1j = γ10 + γ11(Vocabulary/Experiencej) + p1j

β2j = γ20 + γ21(Working-Memoryj)

β3j = γ30 + γ31 (Working-Memoryj) + γ32 (Vocabulary/Experiencej) +p3j

β4j = γ40 + γ41(Working-Memoryj) + γ42 (Decodingj) + γ43 (Vocabulary/Experiencej) + γ44 (Working-Memory × Decodingi) + γ45 (Working-Memory × Vocabulary/Experiencej)

β5j = γ50

β6j = γ60 + p6j

Parameter estimates that were derived from this model are presented in Tables 5 and 6. Effects at sentence N are presented in Table 5, and effects that spilled-over from sentence N-1 to N are presented in Table 6.1 The variance-covariance matrix for the random effects are presented in Table 7. To reiterate, all of the predictor variables were grand-mean centered before they were entered into the model, meaning that the estimates associated with each parameter represent the average change in sentence RT when all other predictors are held to the sample mean.

Table 5.

Backwards-built HLM: Parameter Estimates of Effects at Sentence N

| Parameter | Coefficient | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept(γ00) | 4518.3707 | 69.6558 | 64.867 | <.001 |

| Decoding(γ01) | 0.4077 | 0.1881 | 2.168 | .032 |

| Vocabulary/Experience(γ02) | −31.6344 | 6.3090 | −5.014 | <.001 |

| Length(γ10) | 183.2358 | 3.4410 | 53.251 | <.001 |

| Vocabulary/Experience(γ11) | −1.3281 | 0.3422 | −4.124 | <.001 |

| Log-Frequency(γ50) | −54.2380 | 4.0624 | −13.351 | <.001 |

| New-Noun Concepts(γ30) | 45.0952 | 15.2684 | 2.954 | .004 |

| Working-Memory(γ31) | 5.7211 | 2.1948 | 2.607 | .011 |

| Vocabulary/Experience(γ32) | 4.7747 | 1.5748 | 3.032 | .004 |

Deviance: 209953

Table 6.

Backwards-built HLM: Parameter Estimates of Spillover Effects from Sentence N-1 to N

| Parameter | Coefficient | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length(γ20) | 5.8624 | 1.5614 | 3.755 | <.001 |

| Working-Memory(γ21) | −0.6999 | 0.2645 | −2.642 | .009 |

| Log-Frequency(γ60) | −61.5543 | 8.0338 | −7.662 | <.001 |

| New-Noun Concepts(γ40) | 65.9669 | 12.4812 | 5.285 | <.001 |

| Working-Memory(γ41) | −0.7040 | 1.9997 | −0.352 | .725 |

| Decoding(γ42) | 0.0675 | 0.0405 | 1.669 | .095 |

| Vocabulary/Experience(γ43) | 0.2885 | 0.6896 | 0.418 | .675 |

| Working-Memory × Decoding(γ44) | −0.0212 | 0.0067 | −3.177 | .002 |

| Working-Memory × Vocabulary/Exp.(γ45) | −0.3766 | 0.1256 | −3.000 | .003 |

Deviance: 209953

Table 7.

Variance-covariance matrix for random slopes (tau coefficient)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intercept (p0j) | - | ||

| 2. N Length (p1j) | 21391.26 (.98)* | - | |

| 3. N New-Noun Concepts (p3j) | −4983.01 (−.07) | −523.62 (−.15) | - |

| 4. N-1 Log Frequency (p6j) | −10521.02 (−.35) | −592.51 (−.42) | − 66.65 (−.01) |

Readers will note that the random effects for length and the intercept are highly correlated (tau = .98). This indicates that a person with a large intercept also tends to have a large coefficient for N Length.

Effects at Sentence N

Intercept

The average reading time for each sentence was just over 4500 msec. One unit increase in vocabulary/experience reduced this mean RT by around 31 msec. Similarly, a one unit increase in nonword naming latencies served to increase mean RTs.

Length

Each syllable increase in length served to increase RTs by around 183 msec, with increases in vocabulary/experience serving to attenuate this effect by just under 32ms.

Log-frequency

One unit increase in log-frequency served to decrease RTs by around 54 msec. None of the individual difference variables interacted with this effect.

New-noun concepts

New-noun concepts produced measurable increases in sentence RT, with one new-noun predicting a 45 msec increase in mean RT. Inter-individual variability in the new-noun concept effect was very pronounced (SE = 15.27, see Table 5), and when individual difference factors were taken into account, the model revealed that this effect was exaggerated by working-memory capacity and by vocabulary/experience. A one unit increase in working-memory predicted a 6ms increase in the new-noun concept effect, and a one-unit increase in vocabulary/experience predicted an approximately 5ms increase in the effect. Importantly, the beta coefficients that quantified the new-noun effect were positively correlated with comprehension accuracy (r = .35, see Table 8), meaning that readers who showed slow integration times for new-nouns also scored higher on the comprehension test. When the comprehension question data were divided into question types, the new noun effect was positively correlated with accuracy on questions tapping main ideas (r = .40, p <.001) and inferences (r = .31, p =.004), but not with questions tapping details (r = .14, p =.19).

Table 8.

Pearson’s r correlations between regression coefficients and comprehension accuracy

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Comprehension Acc. | - | ||||||

| 2. Intercept Coeff. | −.002 | - | |||||

| 3. Length Coeff. | .120 | .072 | - | ||||

| 4. N-1 Length Coeff. | −.067 | −.103 | .159 | - | |||

| 5. New-Noun Coeff. | .350** | −.001 | −.317** | −.371** | - | ||

| 6. N-1 New-Noun Coeff. | −.001 | .157 | .002 | −.746** | .069 | - | |

| 7. N Log-Frequency | −.053 | −.481** | −.195* | .030 | .186 | −.389** | - |

| 8. N-1 Log-Frequency | −.159 | −.739** | −.122 | −.045 | −.161 | .123 | .136 |

p</=.01;

p</= .05

Effects from sentence N-1 to N (spillover effects)

We examined spillover effects by analyzing RTs for sentence N as a function of properties of N-1. The analysis revealed a number of main effects and cross-level interactions.

Length

On average, a one syllable increase in the length of sentence N-1 resulted in a 6 msec increase in reading times for sentence N. Working-memory attenuated the spillover, demonstrating that readers who were high in working-memory capacity experienced less spillover than readers who were low in working-memory capacity. The effect of working-memory on length was very small, with a one unit increase in working-memory predicting less than 1ms decrease in the effect of length. It was, however, statistically significant.

Log-frequency

A one unit increase in log-frequency at sentence N-1 served to decrease RTs for sentence N by around 61 msec. No individual difference variables interacted with this effect.

New-noun concepts

On average, each new-noun concept at sentence N-1 increased average RTs for sentence N by approximately 66 msec. There was a 3-way, cross-level interaction between new-noun concepts, working-memory capacity and decoding such that poor decoders experienced more spillover from sentence N-1 to N, but this effect was attenuated by working-memory capacity. There was also a 3-way, cross-level interaction between new-noun concepts, working-memory capacity and vocabulary/experience such that as vocabulary/experience increased, so too did new-noun concept spillover. Again, this effect was attenuated by working-memory capacity.

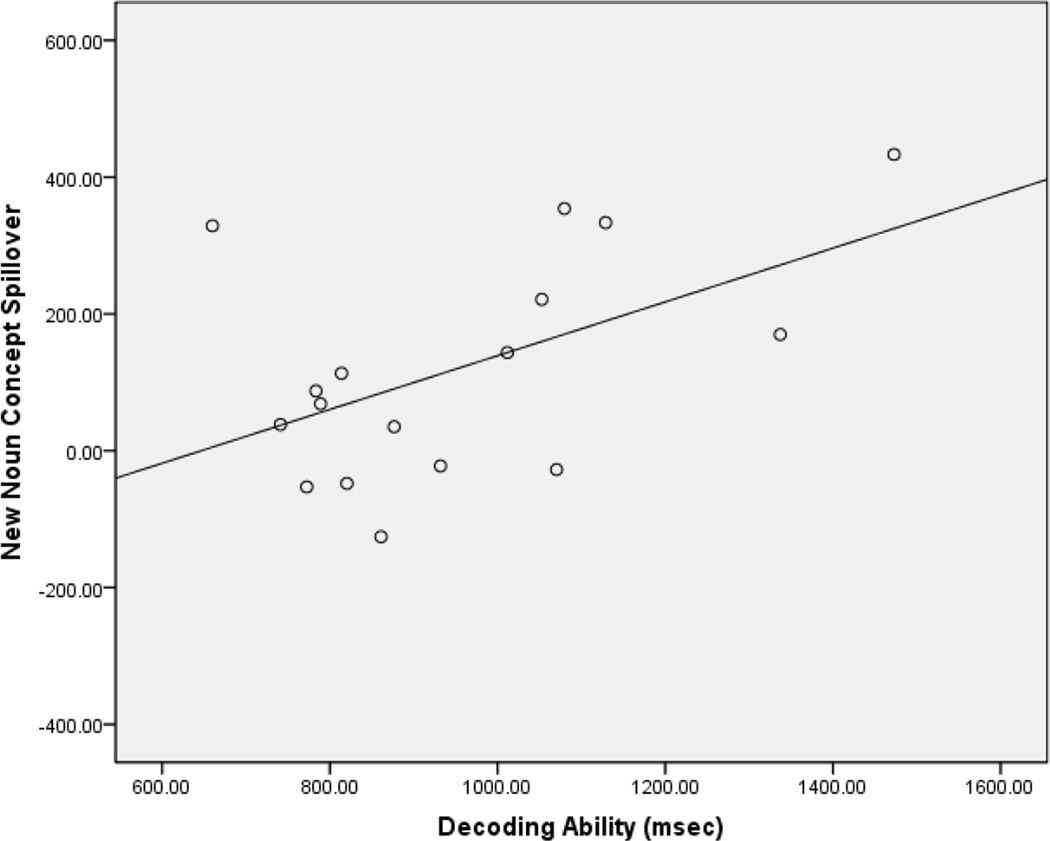

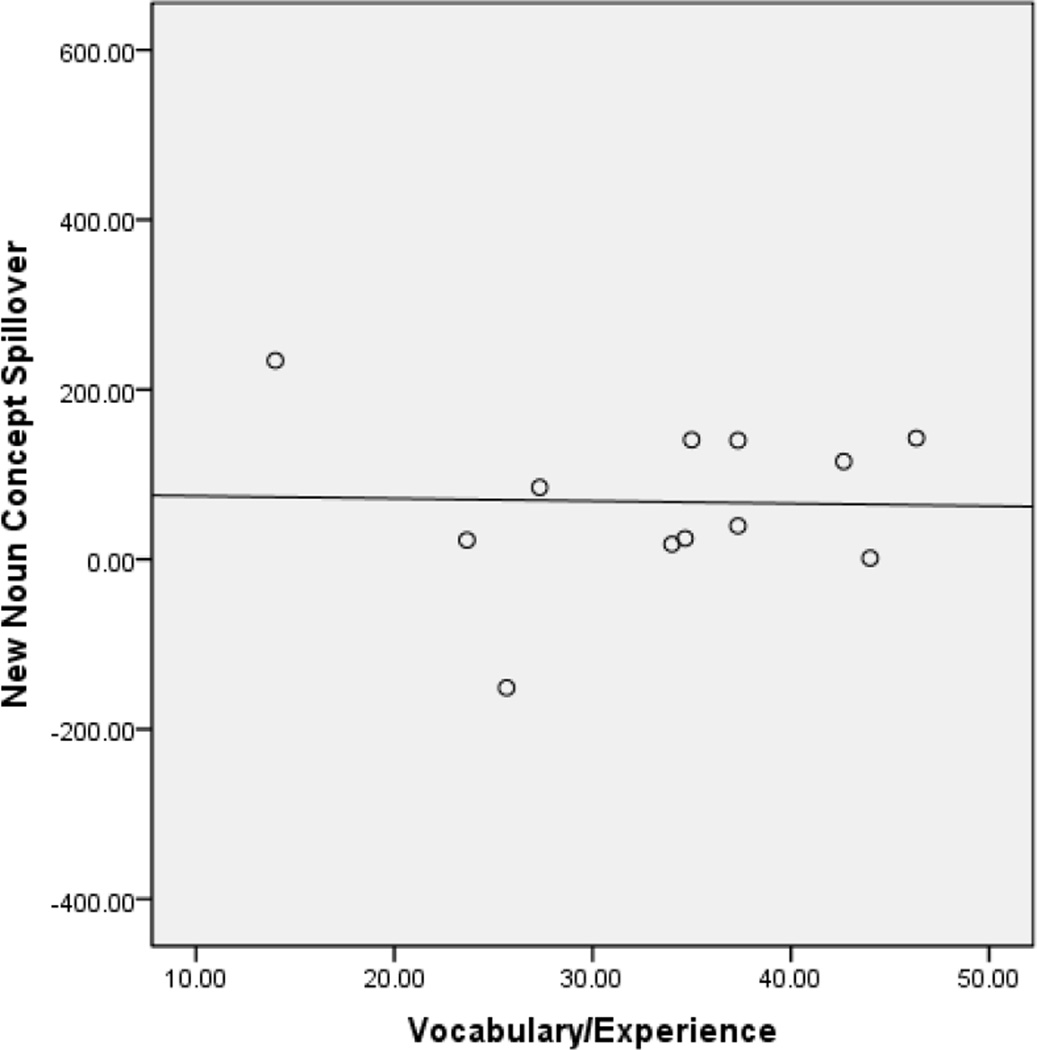

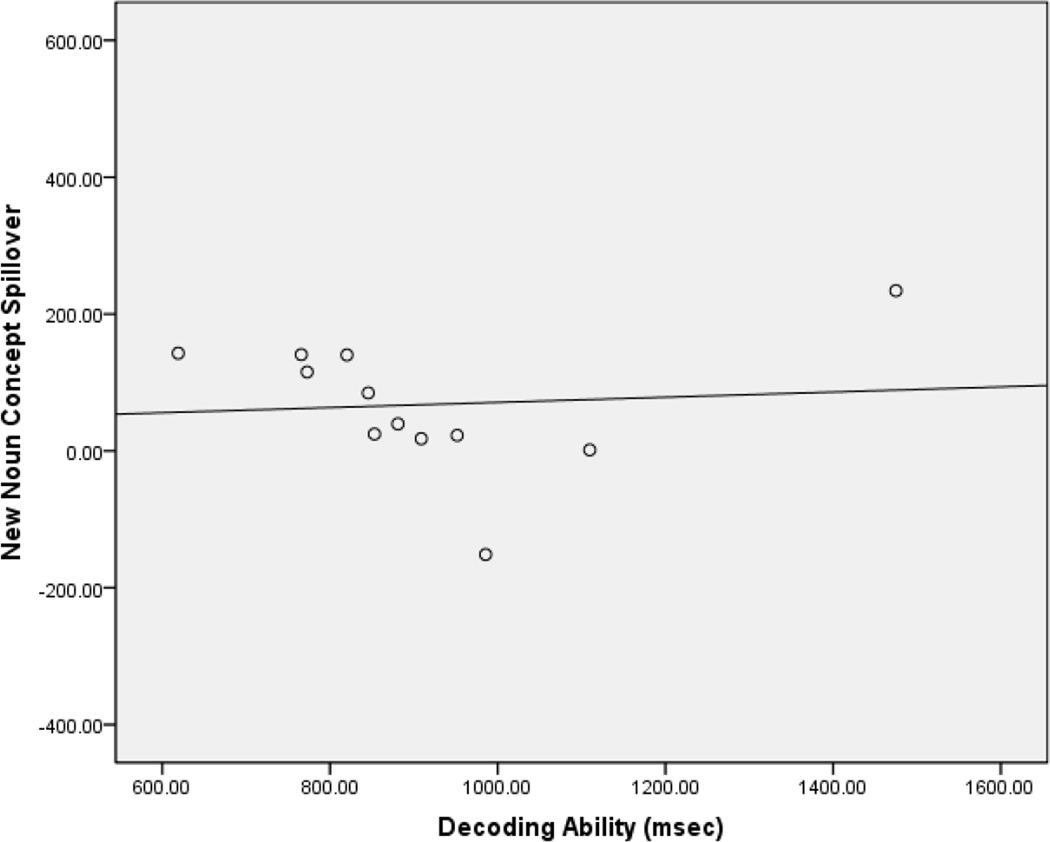

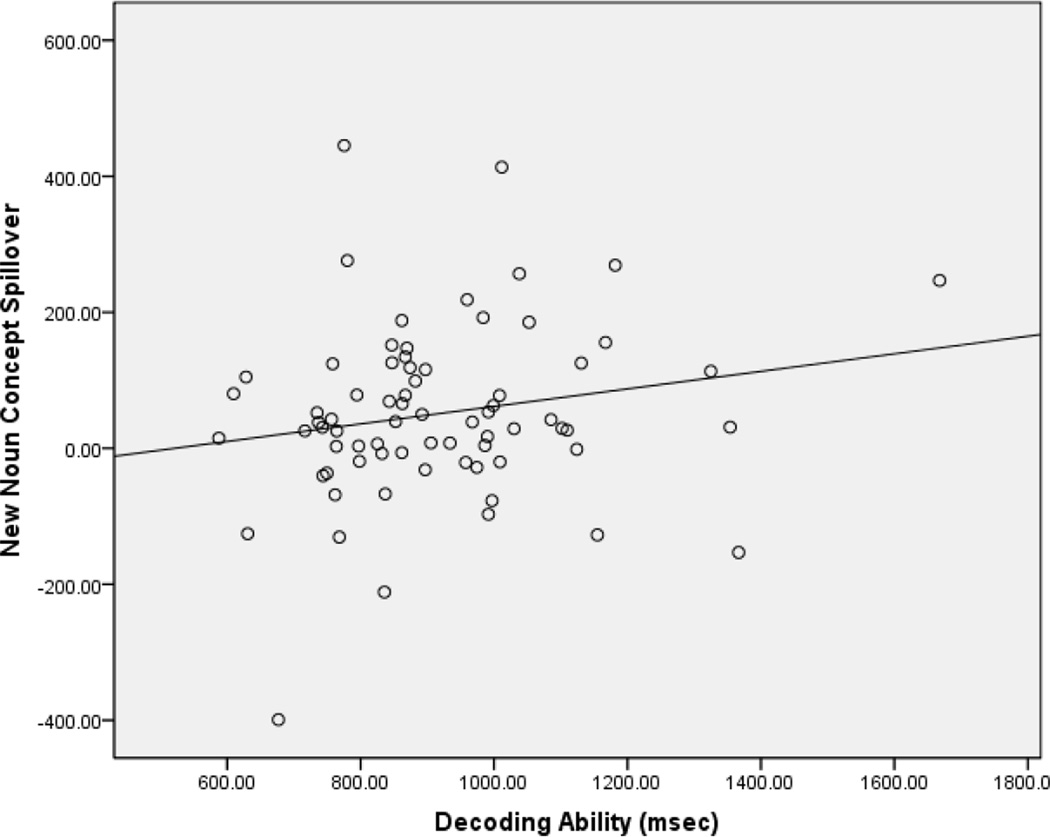

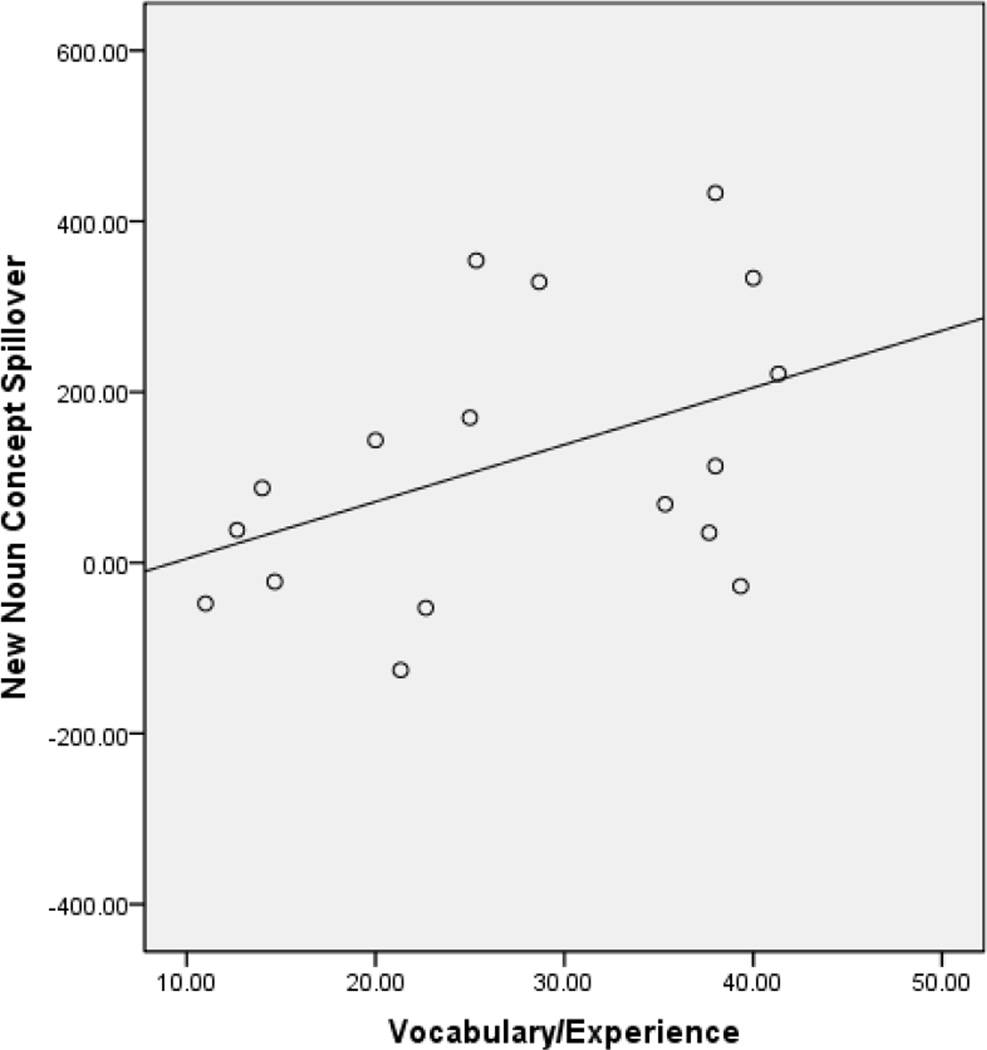

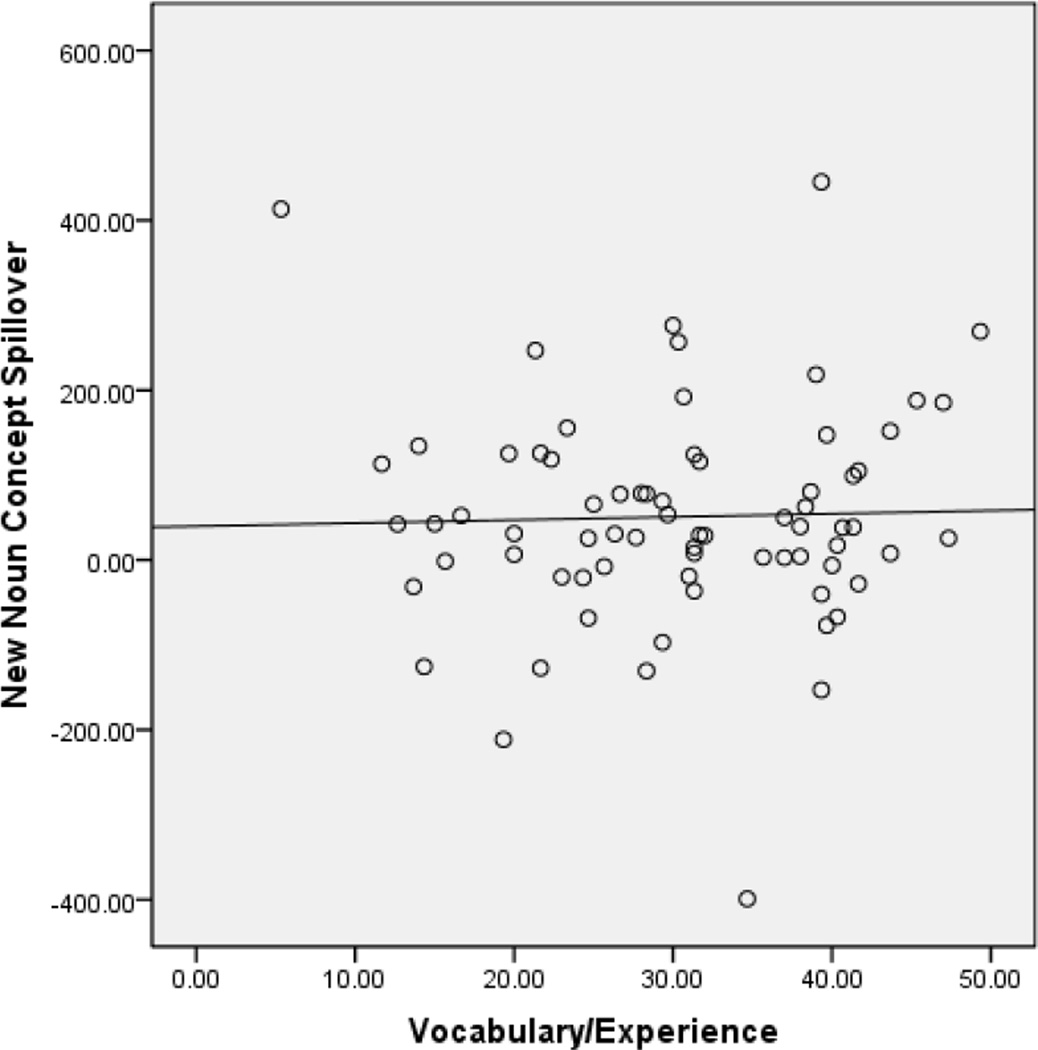

These effects are depicted graphically in Figures 1 to 6. For these plots, level-1 variables were regressed on reading times for each participant separately, and the coefficients that resulted from this procedure were used as individual data points. In order to depict the 3-way interaction, participants were placed into 3 working-memory groups on the basis of their deviance from the mean (i.e., from +1SD, to −1SD).

Figure 1.

New-Noun Concepts × Decoding × Working-Memory Interaction: Low Working-Memory (</= 1SD below the sample mean)

Figure 6.

High Working-Memory (>/= 1SD above the sample mean)

The 3-way, cross level interaction between new-noun concept spillover, working-memory, and vocabulary/experience warranted further investigation. We hypothesized that readers who were high in both working memory and vocabulary/experience completed their integration of new noun concepts at the focal sentence (i.e., N-1). For those readers high in vocabulary/experience, but low in working-memory capacity, this integration was not completed before readers moved on to the subsequent sentence (N); thus, reading times of sentence N were influenced by the new noun concepts contained in sentence N-1. To explore this possibility, the participants were placed into groups on the basis of median splits around working-memory and vocabulary/experience. For readers high in word knowledge and low in working-memory, the correlation between the beta coefficients representing the new noun effect at N and the beta coefficients for the new noun effect from N-1 to N trended toward significance (r = .37, p = .055), suggesting that extended processing of new nouns at N-1 was related to their processing at sentence N. No such relationship was found for readers high in both working-memory and vocabulary/experience (r = −0.05, p = .98). Fisher’s z transformation (Fisher, 1915) demonstrated that the difference between the coefficients for the groups trended toward statistical significance (z = 1.35, p = .089). Thus, our initial interpretation of this effect appears to be supported in the data: Readers who were high in both working-memory and vocabulary/experience completed new-noun concept integration before moving-on to the subsequent sentence, whereas those readers who were low in working-memory but high in vocabulary continued to process the new noun concepts in N-1 as they read sentence N.

Discussion

Prior research has indicated that poor word-decoding skill is a limiting factor in the comprehension abilities of beginning readers. Few studies, however, have examined the role of these skills in text comprehension for skilled adult readers. We have demonstrated that word-level abilities interact with sentence properties to influence text processing in college-level adult readers. Moreover, we have found a compensatory effect of working-memory capacity in modulating the relation between word-decoding and on-line sentence comprehension. Thus, we have confirmed one of the central tenets of the Lexical Quality Hypothesis; that deficiencies in the processes that contribute to lexical access affect higher-order comprehension processes by monopolizing cognitive resources.

Our primary prediction in this study was that poor decoding ability would influence new-noun integration. Based on the assumption that cognitive resources could be measured by the reading-span and operation-span tasks, we also predicted that decoding ability and working-memory capacity would interact to influence new-noun integration times. These predictions were supported by a three-way, cross-level interaction between new-noun concept spillover, working-memory capacity, and decoding skill. Nonword naming latencies predicted new-noun spillover, and this effect was attenuated by working-memory capacity such that working-memory capacity had a compensatory effect (see Table 6 and Figures 1 to 3). This result is readily interpreted in light of the Lexical Quality Hypothesis: Deficiencies in the decoding processes that contribute to lexical access consume cognitive resources, producing ‘sluggish’ new-noun concept integration that spills-over into subsequent sentences. When readers are high in working-memory capacity, this spillover is attenuated.

Figure 3.

New-Noun Concepts × Decoding × Working-Memory Interaction: High Working-Memory (>/= 1SD above the sample mean)

Our finding that word decoding is an important predictor of the new-noun integration effect is consistent with the Lexical Quality Hypothesis, but it is seemingly at odds with the literature presented in the introduction suggesting that decoding processes affect comprehension only when reading skills are very poor (e.g., Bell & Perfetti, 1994). There are a number of differences between the current study and those presented in the introduction, the most conspicuous being our use of Hierarchical Linear Modeling to quantify the interactions between text properties and reader characteristics during on-line reading. Off-line measures of comprehension, such those used in Bell & Perfetti (1994), Braze et al. (2007), and Landi (2010), may be insensitive to the relation between decoding ability and reading performance in skilled adult readers. This may not be surprising given that standardized measures of comprehension often allow readers to consult the passages as they answer comprehension questions about them. This allows for the possibility that higher-level strategic factors play a much larger role in such measures than they do in on-line measures of reading, masking the influence of low-level decoding processes.

Although our focus in this study was on the role of word-decoding in comprehension, we also indentified an important role for vocabulary and print exposure. At sentence N, the addition of new-noun concepts served to increase reading times, and this effect was exaggerated by working-memory capacity and vocabulary/experience. These are individual difference variables that should presumably serve to make the reading process more efficient, so the fact that they acted to increase new-noun integration times is somewhat counterintuitive. Importantly, the beta-coefficients associated with this effect were positively correlated with comprehension accuracy. Intriguingly, this effect was strongest with regard to questions tapping main ideas and inferences; the relation between the new-noun effect and accuracy on questions tapping details failed to reach statistical significance.

Working-memory capacity may have afforded readers the resources needed to properly attend to each new noun concept, either on-line or during sentence wrap-up. Such an interpretation can be incorporated into the majority of models of working memory and reading comprehension, the most prominent being the capacity constrained model of Just and Carpenter (1992). This model holds that reading skill differences can be partly attributed to individual differences in the amount of activation that is available to the reading system. Under this proposal, each representational element (word, phrase, proposition, or in this case, new noun concept) has an associated activation level. If an element’s activation level is above some minimum threshold then it can be operated on by processes in working memory (Just & Carpenter, 1992). In the current study, readers with large working memory capacities may have had the resources to devote sufficient activation to each new noun concept, allowing its integration into the discourse model to be rich and coherent enough to affect comprehension question accuracy.

The cross-level interaction between vocabulary/experience and new-noun concepts can be interpreted with reference to retrieval-based knowledge access and lexical quality. According to the construction-integration (CI) model (Kintsch, 1988; 1998), linguistic input serves to activate related concepts and propositions in a manner akin to priming, with items from the text acting as retrieval structures for information in long-term memory. This knowledge can then form the basis for inferences, elaborating a reader’s discourse representation (e.g., Long, Oppy, & Seely, 1994), or enriching the representation by mapping it onto relevant background knowledge (McNamara et al., 1996). Though the CI model is silent with regard to individual differences in text comprehension, the current data suggest how they may arise. When readers encounter a new noun they access concepts and information that are relevant to it. When readers have good word knowledge and their lexical representations are well specified, activated concepts are integrated with a rich pool of background knowledge. This process drives increases in sentence RT, and assists readers in answering comprehension questions related to the texts, particularly those related to main ideas and inferences that tap knowledge that goes beyond what is stated explicitly. Put simply, there is a cost in processing that is offset by a gain in comprehension.

Vocabulary/experience also increased new-noun spillover from sentence N-1 to N and this effect interacted with working-memory capacity, with those highest in working-memory showing the least spillover and those lowest showing the greatest spillover. The analyses concerning skill groups derived on the basis of working-memory and vocabulary/experience suggest that readers who were higher in working-memory capacity were better able to integrate the new nouns into their discourse representation before they proceeded onto the next sentence in the passage. For those lower in working-memory, the elaborative effect of vocabulary/experience at sentence N-1 was unconstrained, and they proceeded onto the next sentence before the new entities had been properly integrated into their mental representations.

Conclusion

Our study provides the first direct evidence that low-level processes contributing to lexical access are a limiting factor in text processing among skilled adult readers, with deficiencies in decoding ability monopolizing cognitive resources that would otherwise be devoted to high-level integration processes. Our study also highlights the importance of vocabulary and print-exposure in skilled reading, suggesting that the construct they tap aids text comprehension by elaborating incoming information. These complex interactions among reader characteristics and text properties appear to be critical in accounting for individual variation in text comprehension. Our study represents an early step in our understanding how these interactions play-out during normal reading, and how they may be quantified in the future.

Figure 2.

New-Noun Concepts × Decoding × Working-Memory Interaction: Mean Working Memory

Figure 4.

New Noun Concept Spillover × WM × Vocabulary/Experience: Low Working-Memory (</= 1SD below the sample mean)

Figure 5.

New Noun Concept Spillover × WM × Vocabulary/Experience: Mean Working-Memory

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant to Debra Long (RO1HD048914). Our thanks to Keith Widaman who provided helpful advice regarding the data analyses.

Footnotes

The model presented here is based on the data of 101 participants. Comprehension question data were recorded for 87 of these participants. The model was also run with the subset of participants for whom both comprehension question data and individual differences measures were recorded. This model produced parameter estimates that were nearly exactly the same as those presented in Tables 5 and 6.

References

- Ashby J, Rayner K, Clifton C. Eye movements of highly skilled and average readers: Differential effects of frequency and predictability. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2005;58A(6):1065–1086. doi: 10.1080/02724980443000476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell LC, Perfetti CA. Reading Skill - Some Adult Comparisons. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86(2):244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Braze D, Tabor W, Shankweiler DP, Mencl WE. Speaking up for vocabulary: Reading skill differences in young adults. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2007;40(3):226–243. doi: 10.1177/00222194070400030401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JI, Fischco VV, Hanna G. Nelson-Denny Reading Test. Chicago: Riverside; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R. A kind of Flying: Selected Stories. W.W. Norton & Company; 2003. ISBN: 0393324796. [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1980;19(4):450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC. Phases of development in learning to read words by sight. Journal of Research in Reading. 1995;18(2):116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW, Tuholski SW, Laughlin JE, Conway ARA. Working Memory, Short Term Memory, and General Fluid Intelligence: A Latent-Variable Approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128(3):309–331. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 3rd Edition. Sage Publications, LTD; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, Miyake A. Comparison of four scoring methods for the reading span test. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37(4):581–590. doi: 10.3758/bf03192728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U. Beneath the surface of developmental dyslexia. In: Patterson K, Marshall J, Coltheart M, editors. Surface Dyslexia, Neuropsychological and Cognitive Studies of Phonological Reading. London: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 301–330. [Google Scholar]

- Haberlandt KF, Graesser AC, Schneider NJ. Reading Strategies of Fast and Slow Readers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 1989;15(5):815–823. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.15.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberlandt KF, Graesser AC, Schneider NJ, Kiely J. Effects of Task and New Arguments on Word Reading Times. Journal of Memory and Language. 1986;25:314–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hersch J, Andrews S. Lexical Quality and Reading Skill: Bottom-Up and Top-Down Contributions to Sentence Processing. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2012;16(3):240–262. [Google Scholar]

- Holst S. Brilliant Silence. Barrytown/Station Hill Press, Inc; 2000. ISBN:1581770553. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis BG. Direct RT (Version 2008) [Computer Software] New York, NY: Empirisoft Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review. 1992;98:122–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA, Woolley JD. Paradigms and processes in reading comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1982;111:228–238. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.111.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen B, Gardner E. Stanford Diagnostic Reading Test-Fourth Edition [Grades 6.5 to 8.9]. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace. As cited in, Braze, D.,Tabor, W., Shankweiler, D. P., & Mencl, W. E. (2007). Speaking up for vocabulary: Reading skill differences in young adults. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1995;40(3):226–243. doi: 10.1177/00222194070400030401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera H, Francis WN. Computational analysis of present-day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Landi N. An examination of the relationship between reading comprehension, higher-level and lower-level reading sub-skills in adults. Reading & Writing. 2010;23:701–717. doi: 10.1007/s11145-009-9180-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long DL, Prat C, Johns C, Morris P, Jonathan E. The importance of knowledge in vivid text memory: An individual-differences investigation of recollection and familiarity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2008;15(3):604–609. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.3.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist EN. Phonological complexity, decoding, and text comprehension. Dissertations Collection for University of Connecticut. 2003 Paper AAI3116833. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti . Reading Ability. New York, NY: Oxford; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti C. Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2007;11(4):357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA, Hart L. The Lexical Quality Hypothesis. In: Verhoeven C, Elbro C, Reitsma P, editors. Precursors of functional literacy. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2002. pp. 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA, Hart L. The lexical basis of comprehension skill. In: Gorfien DS, editor. On the consequences of meaning selection: Perspectives on resolving lexical ambiguity. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti C, Yang C, Schmalhofer F. Comprehension Skill and Word-to-Text Integration Processes. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2008;22:303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM 6 for Windows [Computer Software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich KE, West RF. Exposure to Print and Orthographic Processing. Reading Research Quarterly. 1989;24(4):402–433. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Noh SR, Shake MC. Age differences in the effects of conceptual integration training on resource allocation in sentence processing. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2010;63(7):1430–1455. doi: 10.1080/17470210903330983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurber J. Fables of our time. Harper Colophon Books; ISBN: 9780060909994. [Google Scholar]

- Yang CL, Perfetti CA, Schmalhofer F. Event-related potential indicators of text integration across sentence boundaries. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33:55–89. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CL, Perfetti CA, Schmalhofer F. Less skilled comprehenders’ ERPs show sluggish word-to-text integration processes. Written Language & Literacy. 2005;8:233–257. [Google Scholar]