Abstract

The current study tested a developmental-contextual model of depressive symptomatology among early and middle adolescent Mexican-origin females and their mothers. The final sample was comprised of 271 dyads. We examined the interrelations among cultural (i.e., acculturation dissonance), developmental (i.e., pubertal development and autonomy expectation discrepancies), and interpersonal (i.e., mother-daughter conflict and maternal supportive parenting) factors in predicting adolescents’ depressive symptoms. For both early and middle adolescents, maternal support was negatively associated with mother-daughter conflict and depressive symptoms. Importantly, mother-daughter autonomy expectation discrepancies were positively associated with mother-daughter conflict, but this association was found only among early adolescents. Further, mother-daughter acculturation dissonance was positively associated with mother-daughter conflict, but only among middle adolescents. Findings call for concurrently examining the interface of developmental, relational, and cultural factors in predicting female adolescents’ depressive symptomatology and the potential differences by developmental stage (e.g., early vs. middle adolescence)

Keywords: Latina adolescents, culture, autonomy, parents, depressive symptoms

Adolescent depression is a significant mental health problem that can undermine positive youth development, and can contribute to negative health outcomes (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). Community (e.g., Joiner, Perez, Wagner, Berenson & Marquina, 2001) and nationally based (e.g., Wight, Aneshensel, Botticelo & Sepúlveda, 2005) samples indicate that Mexican-origin adolescents are at risk for depression. Efforts to understand factors affecting Latino youth’s mental health have focused largely on cultural factors (i.e., mainly acculturation), with less attention to influences such as the parent-adolescent relationship (for an exception see Gonzales, Pitts, Hills, & Roosa, 2000). There is a need to study cultural factors in tandem with other variables salient during adolescence because existing theory underscores the interplay of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors in the development and maintenance of depression (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998). This study extended previous work by providing an in-depth examination of how cultural (i.e., acculturation dissonance), developmental (i.e., pubertal development, autonomy expectations discrepancies), and interpersonal (i.e., parent-adolescent conflict and maternal supportive parenting) factors interacted to inform Mexican-origin early and middle adolescent females’ depressive symptoms. Because female adolescents are at greater risk for depressive disorders than male adolescents (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994), a pattern true for Mexican origin youth as well (e.g., Roberts & Chen, 1995), this is of particular significance for Mexican-origin females.

Influences on Mexican-Origin Female Adolescents’ Depressive Symptoms

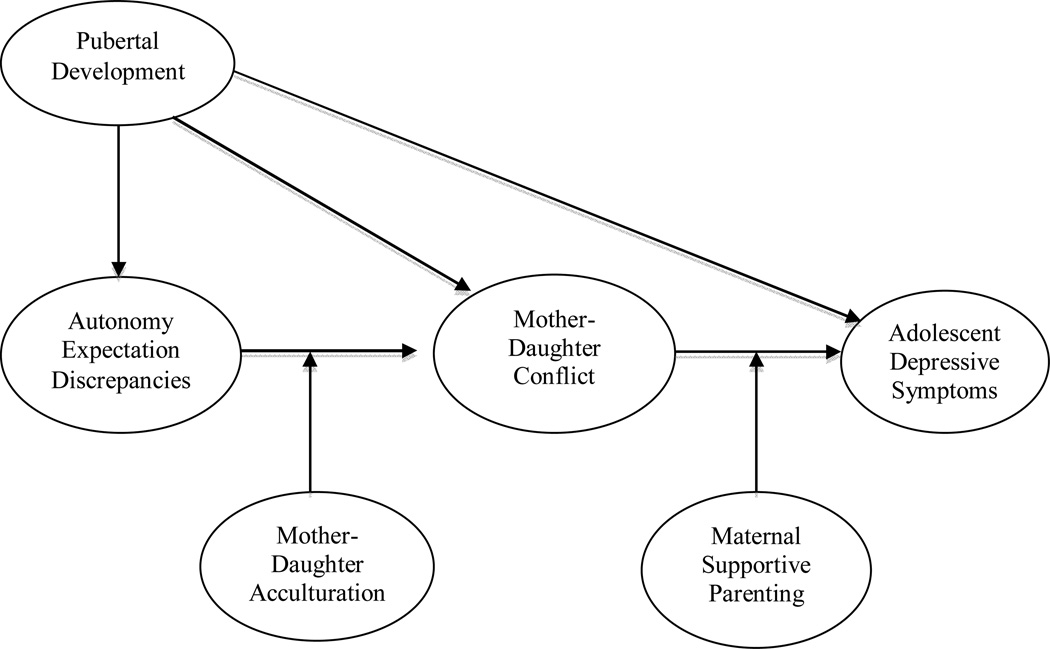

Family systems theory emphasizes multiple influences (e.g., biological, social, cultural) on development (Cox & Paley, 1997), and scholars suggest that it is the convergence of biological, psychological, and social transitions occurring during adolescence that contributes to depressive-related problems (Compas, Ey, & Grant, 1993). Accordingly, the current study proposed and tested a contextual-developmental model of depressive symptoms by examining the interface of developmental influences (i.e., pubertal development, autonomy expectation discrepancies between mothers and their daughters), interpersonal characteristics (i.e., parent-adolescent conflict and supportive parenting), and cultural factors (i.e., acculturation dissonance between mothers and daughters) in predicting female adolescents’ depressive symptoms during early and middle adolescence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

Interpersonal Context and Depressive Symptoms

Interpersonal theories of depression suggest that dysfunctional relationships and negative evaluations of oneself by others can be vulnerability factors for depression (Joiner, Coyne, & Blalock, 1999). Stable and secure relationships with significant others can reduce distress and maximize a sense of security (Allen, McElhaney, Kuperminc, & Jodl, 2004). For instance, a secure relationship with parents can provide youth with confidence that their relationship will not be harmed despite disagreements (Allen & Land, 1999). The interpersonal context is particularly salient for females because their sense of self revolves around needs of connectedness, intimacy, and mutuality (Joiner et al., 1999), which may explain sex differences in depression (Hankin & Abramson, 2001). For Latina adolescents, relationship-centered socialization goals and expectations regarding strong emotional ties to the family (Garcia-Preto, 2005), coupled with rigid gender roles (e.g., greater restrictions on autonomy for females; Zayas, Lester, Cabassa, & Fortuna, 2005), may also contribute to female adolescents’ relatively greater risk for depression.

In terms of the parent-child relationship, findings indicate that some parental qualities (e.g., maternal warmth, support, nurturance) function as protective factors, whereas others (e.g., conflict, inconsistent discipline) increase the risk for Latino youth depression (Crean, 2008; Gonzales et al., 2006). Because Latino families in the U.S. are embedded in a cultural context that may be at odds with the goals and values of their native culture, the parent-adolescent context can be challenged in the presence of issues surrounding cultural factors (i.e., acculturation processes within the family) and developmental tasks salient during adolescence (e.g., adolescents’ v. parents’ autonomy expectations). These differences between parents and adolescents can add to the normative intergenerational conflict experienced during adolescence.

Autonomy Development, Parent-Adolescent Conflict, and Psychological Adjustment

Normative transitions during adolescence affect not only the adolescent, but also pose a challenge for the entire family system (Minuchin, 1985). One of these transitions is adolescents’ determination to gain more freedom (i.e., autonomy) from their parents (Collins, Laursen, Mortensen, Luebker, & Ferreira, 1997). Adolescents’ growing desire for autonomy and parents’ opposition to youth’s autonomy seeking contribute to changes in parent-adolescent relationships, including increased conflict (Collins et al.; Fuligni, 1998; Holmbeck, 1996).

Studies of ethnic minority and immigrant youth have found that parents and adolescents often experience differing views about behavioral autonomy expectations, decision making, and parental authority (e.g., Phinney Ong & Madden, 2000; Smetana & Daddis, 2005). Because Latino families in the U.S. are embedded in two cultural contexts (i.e., home and host society) most likely endorsing differing cultural values, expectations about autonomy may differ considerably between Latina adolescents and their parents. Specifically, due to the importance of autonomy in Western cultures such as the U.S. (Phinney et al., 2000), and obedience to authority among families from Latino cultures (Fuligni, 1998), Latina adolescents may have a desire for autonomy, discovery, and freedom (Ayala, 2006; Gallegos-Castillo, 2006), but this desire may be met with relatively high levels of parental opposition and control (Ayala; Azmitia & Brown, 2000).

Indeed, discrepancies in autonomy expectations have been linked to increased parent-adolescent conflict (Holmbeck & O’Donnell, 1991). Furthermore, in other studies, parent-adolescent conflict, has been associated with Latino adolescents’ psychological adjustment (e.g., Crean, 2008; Loukas & Roalson, 2006; Pasch et al., 2006). Finally, there is some evidence suggesting that parent-adolescent discrepancies regarding issues such as autonomy expectations are associated with adolescents’ psychological adaptation (Phinney & Vedder, 2006). We are unaware of any studies, however, that have simultaneously examined these associations among Latino youth and families. Thus, an important next step is to examine how parent-adolescent autonomy expectations and parent-adolescent conflict may work together to contribute to Latina adolescents’ psychological functioning. Given the previous literature, we hypothesized that autonomy expectation discrepancies would positively predict mother-daughter conflict, which in turn would be positively associated with adolescents’ depressive symptomatology.

Acculturation Dissonance as a Risk Factor

With respect to the cultural context within which this process is unfolding, theoretical work has linked acculturation to autonomy expectations and parent-adolescent conflict. Specifically, scholars suggest that the differential rates of cultural adaptation to the mainstream culture (i.e., acculturation) among family members (i.e., acculturation dissonances between parents and children; Birman, 2006; Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1980; 1993) may lead to differing values and expectations within the family. This may contribute to difficulties in the family, such as intergenerational conflict (Buriel & DeMent, 1997; Szapocznik & Kurtines, 1993). Specifically, as adolescents embrace the cultural values and behaviors of the dominant society as a way of fitting in (Cabassa, 2003), intergenerational clashes may heighten due to differences between what adolescents want for themselves and what parents want for them (Baptiste, 1993). Furthermore, acculturation processes may disrupt more proximal aspects of adolescents’ lives (e.g., family processes), and these disruptions may be what places adolescents at risk for maladjustment (Santisteban & Mitrani, 2003).

Szapocznik and Kurtines (1993) argue that acculturation dissonances between parents and children add to the normative intergenerational conflict that occurs in families with adolescents by exacerbating intergenerational and intercultural conflict in the family. Thus, suggesting that acculturation-related processes (i.e., acculturation dissonance) are likely to operate interactively rather than directly on psychological adjustment. Specific to Latina mothers and daughters, the association between mother-daughter autonomy expectation discrepancies and mother-daughter conflict may be exacerbated by the acculturation dissonance that exists between mothers and daughters, posing a risk to the mother-daughter relationship (De la Rosa, Vega, & Radisch, 2000). In families with larger mother-daughter behavioral autonomy expectation discrepancies, and greater acculturation dissonances, mother-daughter conflict may be experienced to a greater extent than in families with smaller acculturation dissonances. A study with Asian Indian adolescents supports this idea; adolescents in families with no acculturation dissonance reported less frequent and intense parent-adolescent conflict than those in families where there was an acculturation dissonance (Farver, Narang, and Bhadna, 2002). Thus, we hypothesized that mother-daughter acculturation dissonance would exacerbate the relation between autonomy expectation discrepancies and mother-daughter conflict, with this relation expected to be stronger for dyads with a larger, rather than smaller, acculturation dissonance.

Supportive Parenting from Mothers as a Protective Factor

Whereas parent-adolescent conflict can pose a threat to the psychological well-being of Latino youth, some aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship (e.g., warmth and support) can serve a protective function. Consistent with this notion, existing work suggests that families represent the foundation of resilience in the lives of Latino youth (e.g., Marsiglia, Miles, Dustman, & Sills, 2002), and nurturing parent-adolescent relationships are important contributors to resilience and well-being (Nickerson & Nagle, 2004). Theoretical work suggests that a relationship characterized by high levels of warmth and support from parents may act as a protective factor by providing adolescents with a sense of acceptance and conveying to youth that support is available, reducing the threat of stress (Wolchik, Wilcox, Tein, & Sandler, 2000). Although studies examining the moderating role of supportive parenting is limited (e.g., Scaramella, Conger & Simons, 1999; Wolchik et al., 2000), parental warmth, support, and nurturance have been consistently associated with fewer depressive problems among Mexican-origin youth (e.g., Benjet & Hernandez-Guzman, 2001; Gonzales et al., 2006). Given the theorized protective nature of parental support, we hypothesized that the positive association between parent-adolescent conflict and Mexican-origin adolescents’ depressive symptoms would be moderated by the quality of the mother-adolescent relationship, such that the association between conflict and depressive symptoms would be weaker among dyads with higher maternal support.

Pubertal Development

Adolescents and their social environments must adapt to changes in pubertal maturation (Ge, Elder, Regnerus, & Cox, 2001). Related to adolescents’ adaptation, studies with ethnically diverse samples have linked pubertal development to adolescent depressive-related problems, especially among females (Benjet & Hernandez-Guzman, 2001; Hayward, Gotlib, Schraedley, & Litt, 1999; Nadeem & Graham, 2005). In fact, the sex differences in depression that begin to emerge during early adolescence have, in part, been attributed to sex differences in pubertal timing (Petersen, et al., 1993). Research has also found a link between pubertal development and changes in the parent-adolescent relationship, such as temporary heightened parent-adolescent conflict (Holmbeck, Paikoff, & Brooks-Gunn, 1995). Changes in the parent-adolescent relationship are likely to be present shortly after the onset of puberty for girls (Holmbeck & Hill, 1991; Paikoff & Brooks-Gunn, 1991). Conflict between parents and their daughters may intensify as girls go through biological and physical changes because parents may find it necessary to impose more control over their daughters due to fears of dating and sexual pressures (Holmbeck & Hill). For early maturing females, conflict may also intensify as parents become more concerned about their daughters’ well-being and girls feel unable to express themselves freely (Granic, Dishion, & Hollenstein, 2003).

Little is known about whether pubertal development is associated with amplified conflict or autonomy issues among ethnic minority parent-adolescent dyads. One study that included Latino parent-adolescent dyads, however, found that more developed girls reported relatively more conflict with their mothers and their fathers (Molina & Chassin; 1996). Although limited, these findings suggest a possible association between pubertal development and parent-adolescent conflict among Latino samples. As such, we hypothesized that pubertal development would be positively associated with mother-daughter autonomy expectation discrepancies, mother-daughter conflict, and depressive symptoms.

Examining Relations across Two Developmental Periods: Early and Middle Adolescence

The current study also examined potential differences in the associations of interest based on developmental period. Collins (1991) suggests that the mutuality of perceptions between parents and their children may vary as a function of adolescents’ developmental status. The mismatch in beliefs and goals between adolescents and parents (i.e., discrepancy values) is believed to increase during the transition to adolescence because adolescents begin to spend a greater time outside the home during this time, uncovering a wider range of goals and beliefs that may not be in line with those of their parents (Granic, et al., 2003). However, parents’ and adolescents’ views gradually converge throughout adolescence, as one or both parties realign their expectations (Collins & Luebker, 1994). Thus, autonomy discrepancy values may be more strongly associated with changes in the parent-adolescent relationship (i.e., conflict) during early adolescence than in middle adolescence.

Furthermore, although parents are an important interpersonal context in the lives of adolescents (Grotevant, 1998), youth’s time spent and emotional connection with parents, friends, and others shifts during adolescence (Schneiders et al., 2007). For instance, by middle adolescence, adolescents’ interactions with romantic partners become more frequent than interactions with parents, siblings, and friends (Laursen & Williams, 1997). Thus, features of the parent-adolescent relationship may be stronger predictors of psychological adjustment in early adolescence than later when adolescents’ multiple worlds of family, school, and peers become increasingly important (Phelan, Davidson, & Yu, 1997). In fact, in an ethnically diverse sample of early and late adolescents, the magnitude of association between family process variables (e.g., parental warmth, conflict with parents) and depressed mood was significantly greater in early than late adolescents (Greenberger & Chen, 1996). Given this prior work, developmental period (i.e., early versus middle adolescence) was examined as a moderator in all analyses.

Variability by Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics such as family structure (e.g., two-parent vs. single parent household), socioeconomic status (SES), maternal age, and nativity status are important demographic factors that can inform developmental outcomes among ethnic minority youth (Garcia-Coll et al., 1996). There is some evidence that these demographics factors may be associated with youth depressive symptoms and parent-adolescent conflict. For instance, girls from single-parent families and low SES families are at greater risk for depression than those from two-parent families and higher SES backgrounds (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998; Rumbaut, 1997). Parental education (often used as an indicator of SES) and living in a two-parent household have been linked in a similar manner with parent-adolescent conflict in previous work (e.g. Rumbaut, 1997). Findings with respect to nativity status are more mixed, with some pointing to an immigrant advantage, in which youth in foreign-born families demonstrate lower psychological distress than their U.S. born counterparts (e.g., Harker, 2001), but others finding no differences (Peña et al., 2008). Though little is known about the role of maternal age on youth depressive symptoms, there is some evidence that a maternal age of 30 and older has been linked with youth major depression in late adolescence (Reinherz, et al., 1993). Because each of these sociodemographic characteristics could introduce variability into the relations of interest in the current study, they were included as covariates in all analyses.

The Current Study

Based on existing literature, we hypothesized that discrepancies in behavioral autonomy expectations would be positively associated with mother-daughter conflict, and that this association would be stronger among early adolescents than middle adolescents. Further, we hypothesized that mother-daughter conflict would be positively associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms and that this association would be stronger among early adolescents than middle adolescents. We expected mother-daughter acculturation dissonance to moderate the link between autonomy expectation discrepancies and mother-daughter conflict such that the positive association would be significantly stronger among dyads with a larger acculturation dissonance, compared to those with a smaller acculturation dissonance. In addition, we hypothesized that maternal support would moderate the positive association between mother-daughter conflict and daughters’ depressive symptoms, such that the association would be significantly weaker among those with relatively higher levels of maternal support. Finally, we hypothesized that pubertal development would be positively associated with autonomy expectation discrepancies, mother-daughter conflict, and depressive symptoms. All analyses controlled for: maternal age, nativity, and education; adolescent nativity; and family composition (e.g., two-parent vs. single parent).

Method

Participants

A total of 338 female adolescents (170 7th graders; 168 10th graders) from 10 public schools (4 middle schools and 6 high schools) in a large Southwestern, metropolitan area in the U.S. participated in this study. Latino students represented 67% to 88% of the student body in each of the participating schools. Of all eligible participants (i.e., females in 7th or 10th grade identified as Latina by school records), participation rates by school ranged from 17.1% to 25.9% for the 7th grade sample and from 6.1% to 17.9% for the 10th grade sample. Almost all adolescents (n = 319) participated in the study with their mothers/mother figures. For the current study, only data from dyads with a biological mother (n = 308) were used. Based on preliminary analyses (see below), the final sample consisted of 271 dyads (129 7th graders; 142 10th graders), for which sample descriptive are provided below.

The 7th grade sample ranged in age from 12 to 14 years (M = 12.26, SD = .46) and 63.6% (n = 82) reported being U.S.-born. The 10th grade sample ranged in age from 14 to 17 years (M = 15.20, SD = .43) and 60.6% (n = 86) were U.S.-born. Slightly over 60% of youth lived in households with both their biological mother and father (64.3% and 61.3% for 7th and 10th graders, respectively), but other family constellations were reported (e.g., 23% of 7th graders and 18% of 10th graders lived only with their biological mother). Our figures mirror the percentage of Latino children in the U.S. who live with both biological parents (i.e., 61%; Kreider, 2008).

Mothers ranged in age from 27 to 53 years (M = 37.27, SD = 5.74) and from 31 to 57 years (M = 39.65, SD = 4.24) for the 7th and 10th grade sample, respectively. Most mothers (88.9%) were born in Mexico. Mothers’ educational attainment ranged from no formal schooling to obtaining a bachelor’s degree. The majority of mothers (i.e., 70.8%) had some formal schooling but had not completed high school; 17.0% had a high school degree or equivalent; 9.6% had some college; and 2.6% had a Bachelor’s degree.

Procedure

Letters were mailed home by school personnel describing the study and requesting that families return an informational sheet if they were interested in participating (for a detailed description of recruitment procedure, see Author Citation). To be eligible to participate, female adolescents had to be in either 7th or 10th grade, both of their parents had to be of Mexican descent, and their mother/mother figure had to agree to participate. All documents that were not originally available in Spanish were translated by the first author and back-translated by a researcher of Mexican origin (Author citation). Data collection for adolescents took place at schools during class, lunch, or after school. Mothers were interviewed via phone, by the first author, in mothers’ language of preference.

Measures

Adolescents’ and mothers’ surveys included various measures and assessed numerous demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, nativity, family constellation).

Behavioral autonomy expectations

Adolescents and their mothers completed an adapted version (20 items) of the Teen Timetable Questionnaire (Feldman & Quatman, 1988). Adolescents were asked to decide the age at which they thought they should engage in a variety of everyday management domains (e.g., “at what age do you think you should…go out on dates?”). Mothers completed the same measure with slightly different instructions “At what age do you expect your daughter to…go out on dates?” Participants were asked to respond to questions using a 5-point scale: (1) before age 12, (2) between 12 and 14, (3) between 15 and 17, (4) 18 years or older, and (5) never. A mean score was obtained to yield an overall autonomy expectation score. A difference score was calculated to indicate the level of discrepancy between daughters and their mothers, with greater autonomy expectation discrepancy scores indicating less agreement on autonomy behavioral expectations within the dyad. An adapted version of the original measure obtained an alpha coefficient of .81 for adolescents and .80 for mothers in a sample of middle-class African Americans (Smetana & Daddis, 2005). With the current sample, alpha coefficients were .87 and .78 for adolescents and mothers, respectively.

Parent-adolescent conflict

Adolescents completed a 15-item measure of parent-adolescent conflict, that assessed the frequency of conflict within the dyad across 15 domains (e.g., chores, schoolwork, curfew, dating, and family obligations). Participants were asked how often they had conflicts or disagreements with their mothers with respect to each issue, and were asked to respond using a 5-point Likert scale, with end points of (1) never to (5) most of the time. The measure was originally developed as a 12-item scale by Updegraff, Delgado, and Wheeler (2009) by combining items from measures by Smetana (1988) and Harris (1992) and adding items relevant to Mexican American families (e.g., putting family first and talking back to parents). Updegraff’s version was further revised for use in the current study by deleting a more global item (i.e., behaviors and rules) and adding four specific items (i.e., disobeying, lying to parents, substance use, and cultural traditions). With this sample, alpha coefficient was .86.

Acculturation dissonance

Adolescents and mothers completed the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS; Marín & Gamba, 1996) to assess language-related cultural orientation. The 12-item acculturation subscale of the BAS was used in the current study and assessed English language use (3 items; e.g., “How often do you speak in English with your friends?”), English linguistic proficiency (3 items; e.g., “How well do you understand music in English?”), and English electronic media use (3 items; e.g., “How often do you watch television in English?”). Response choices for the language and electronic media use items ranged from (1) almost never to (4) almost always; response choices for the linguistic proficiency items ranged from (1) poorly to (4) excellent. The 12-item subscale obtained an alpha coefficient of .92 in a study of Latino adolescents (Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007), and alpha coefficients were .91 and .96 for adolescents and mothers, respectively, in the current study. Acculturation dissonance between daughters and mothers was determined by calculating the difference between mothers’ and daughters’ scores on the scale (Merali, 2002).

Maternal supportive parenting

Adolescents completed a 9-item version of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) to assess perceptions of maternal supportive parenting (e.g., “I can count on my mother when I need to talk”). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from almost never or (1) never to (4) almost always or always. The 9-item measure obtained an alpha coefficient of .92 with a Mexican-origin adolescent sample (Gonzales et al., 2006) and .93 with the current sample.

Depressive symptoms

Adolescents’ completed the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) to assess depressive symptoms. Adolescents were asked to think about the past week and items (e.g., “I could not get going”) were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from (0) rarely or none of the time to (3) mostly or almost all the time. High internal consistency has been demonstrated with Latino adolescents (Roberts & Chen, 1995; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007), and in the current study alpha was .90.

Pubertal development

Adolescents completed the 5-item Pubertal Development Scale (PDS, Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988) to assess pubertal developmental changes (e.g., breast development and menarche). Four items were rated on a 4-point scale. A sample item was “In the past two months, have your breasts begun to grow? (1) No; (2) Barely; (3) Yes, definitely; (4) Growth seems complete.” The onset of menarche had a dichotomous response that was scored as (1) no and (4) yes, to be equivalent to other items. Items were summed to produce a continuous score of pubertal development (Petersen et al.). With a sample that included Latino youth, the scale achieved an alpha of .75 for boys and girls, and support for its validity (Siegel, Yancy, Aneshensel, & Schuler, 1999). With the current sample, alpha coefficient was .61.

Results

Initial examination of the raw data indicated that study variables did not violate assumptions of normality. Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for study variables for early (n= 129) and middle (n = 142) adolescents.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother’s Age | -- | .04 | .21* | .25** | .09 | −.04 | −.10 | −.06 | .14 | −.08 | −.06 | |

| 2. Mother’s Education | −.01 | -- | .22** | .06 | −.05 | .16 | −.24** | −.04 | −.05 | .06 | .02 | |

| 3. Mother’s Nativity | −.10 | .22* | -- | .26** | .24** | −.00 | −.48** | −.17* | .02 | .07 | .02 | |

| 4. Daughter Nativity | .23** | −.03 | .29** | -- | .10 | .06 | −.14 | −.06 | .03 | .08 | −.04 | |

| 5. Family Structure | −.05 | .02 | .21* | .11 | -- | −.03 | −.08 | .02 | .00 | −.10 | .04 | |

| 6. Pubertal Development | .11 | −.15 | −.00 | .03 | .04 | -- | .16 | −.00 | .13 | −.00 | −.07 | |

| 7. Acculturation dissonance | .16 | −.37** | −.57** | −.26** | −.13 | .01 | -- | .14 | .14 | −.07 | .01 | |

| 8. Autonomy Discrepancy | −.08 | .06 | −.00 | .02 | .19* | .18* | .01 | -- | .20* | −.25** | .21* | |

| 9. Conflict | −.07 | −.01 | .13 | .04 | .08 | .17 | −.03 | .27** | -- | −.46** | .29** | |

| 10. Supportive parenting | .07 | .12 | .05 | −.09 | .03 | −.22* | −.11 | −.29** | −.35** | -- | −.26** | |

| 11. Depressive Symptoms | −.11 | −.02 | −.03 | .12 | .01 | .08 | −.02 | .29** | .47** | −.40** | -- | |

| Mean | EA | 37.27 | 6.35 | 87.601 | 36.401 | 64.302 | 2.54 | 1.37 | .92 | 2.36 | 3.33 | .80 |

| SD | 5.74 | 3.10 | -- | -- | -- | .54 | .70 | .57 | .76 | .77 | .56 | |

| MA | 39.65 | 5.76 | 90.801 | 39.401 | 61.302 | 3.15 | 1.49 | .82 | 2.42 | 3.13 | .91 | |

| 4.94 | 2.85 | -- | -- | -- | .41 | .73 | .50 | .72 | .79 | .58 | ||

| Skewness | EA | .65 | .54 | 2.31 | −.57 | .90 | −.12 | −.38 | .48 | .62 | −1.35 | 1.05 |

| MA | .48 | .64 | 2.86 | −.44 | .94 | −.39 | −.27 | .54 | .47 | −.71 | .87 | |

| Kurtosis | EA | −.21 | −.81 | 3.38 | −1.70 | −.99 | −.65 | −.83 | −.67 | .01 | .96 | .70 |

| MA | .02 | −.52 | 6.29 | −1.84 | −.72 | −.13 | −.74 | .46 | .13 | −.41 | .34 | |

Note. Correlations for middle adolescents are presented above the diagonal and means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis are presented below correlations. EA = early adolescents, MA = middle adolescents.

percent Mexico-born.

percent in two-parent biological homes. The standard error for skewness was .213 and .423 for kurtosis for all variables for early adolescents and .203 for skewness and .404 for kurtosis for middle adolescents.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether any non-normative values in autonomy expectation discrepancies and acculturation dissonance were present in the current data given existing controversy about computing discrepancy scores (Birman, 2006; Holmbeck & O’Donnell, 1991). A non-normative score on acculturation, for example, would indicate that mothers reported higher acculturation scores than their daughters. We found that of the 308 dyads, 13 dyads demonstrated non-normative acculturation dissonance and 26 dyads demonstrated non-normative autonomy discrepancies. Normative and non-normative dyads were compared on demographic variables (e.g., mothers’ age) and variables in the model (e.g., acculturation and depressive symptoms) using Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs). Results indicated that normative and non-normative acculturation (F (10, 308) = 9.133, p < .001) and autonomy expectation (F (10, 308) = 20.120, p < .001) dyads differed significantly from each other. Because of the small sample size for non-normative cases, we were unable to conduct separate analyses to examine the relations of interest with just this group; as a result, they were not included in further analyses and the results described below reflect the 271 dyads who demonstrated normative acculturation dissonance and autonomy discrepancy scores.

Analytic Strategy

Multiple group path analysis (Muthen & Muthen, 2001) using Mplus version 3.1, with developmental period as the grouping variable (i.e., early versus middle adolescence), was utilized to test the hypothesized model. Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was used and model fit was evaluated using the χ2 statistic, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Modification indices, guided by theory, were used to improve model fit in cases where model fit was not adequate (Kline, 1998; Maruyama, 1998). We followed a series of steps, detailed below, to arrive at our final model and to test for group differences in the associations of interest.

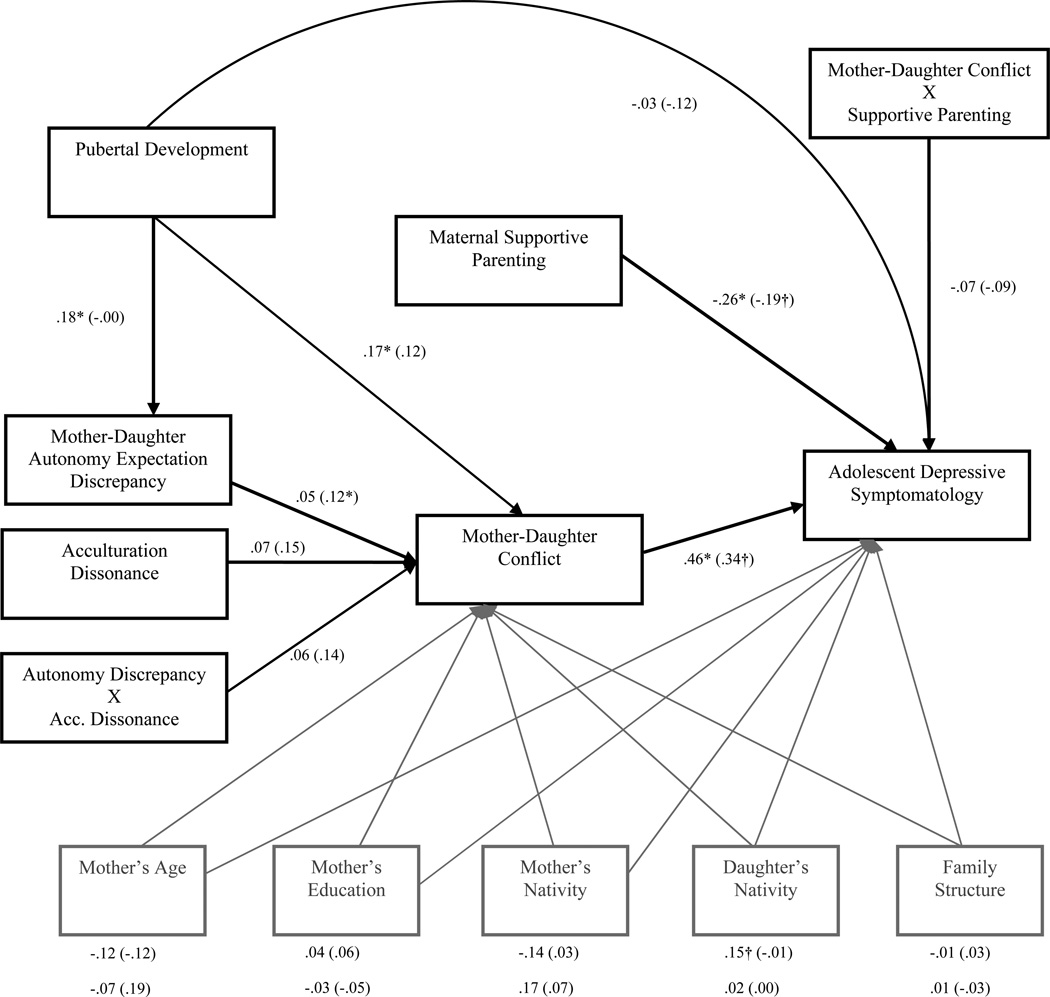

First an unconstrained model was fit to the data. This model tested all study hypotheses and included all control variables; furthermore all paths were freely estimated across groups (i.e., early and middle adolescents) in this model (see Figure 2). Direct paths were estimated from all control variables to depressive symptoms as well as mother-daughter conflict. In addition, the interactions of (a) autonomy expectation discrepancy with acculturation dissonance in predicting mother-daughter conflict and (b) mother-daughter conflict with maternal supportive parenting in predicting depressive symptoms were examined. We revised the unconstrained model based on modification indices and arrived at an alternate model (i.e., Model A) that achieved a satisfactory fit as indicated by the multiple fit indices examined. We then moved toward examining the equivalence of paths across early and middle adolescents (i.e., multiple group analyses).

Figure 2.

Initial Unconstrained Model Predicting Mexican-origin Early and Middle Adolescents’ Depressive Symptoms.

Note. Standardized estimates presented for early and (middle) adolescents. Control variables are in grey, the first row of values under control variables presents the direct effects to adolescent depressive symptoms and the second row presents the direct effects to mother-daughter conflict.

†p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The equivalence of paths across developmental groups was tested using a multiple group approach in which a fully constrained version of Model A (Model A1) was compared to its freely estimated counterpart (Model A). The χ2 difference test was used, with a significant change in the χ2 statistic indicating that the two models are significantly different from one another and fit indices are then examined to determine the better fitting model (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). If the fully constrained model is a poorer fit, this indicates that all paths in the model cannot be constrained to be equal across early and middle adolescents. In an effort to uncover which paths can be estimated to be equal across groups, and which must be freely estimated, subsequent models are tested in a sequential progression whereby each estimated path in the model is tested by imposing an equality constraint across groups and comparing the fit of that model with the unconstrained model. The χ2 difference test is examined for each model comparison to determine whether imposing an equality constraint across groups for a particular path estimate significantly improves model fit or contributes to model misfit (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

Finally, after all multiple group analyses were completed and the paths that should remain freely estimated across groups (i.e., significantly different estimate for early vs. middle adolescents) were identified, we adopted our final model (Model B), and proceeded to test indirect effects in this final model.

Initial Unconstrained Model

Fit indices (see Table 2) indicated that the initial unconstrained model did not fit the data well (see Figure 2). Given the poor fit, modification indices were examined and changes that were in line with the conceptual model or were corroborated by previous literature were made. For example, one modification index suggested adding a direct path from maternal supportive parenting to mother-daughter conflict to improve model fit. Given that previous work has found a significant relation between supportive parenting and parent-adolescent conflict among ethnically diverse samples (e.g., Greenberger, Chen, Tally, & Dong, 2000), we added this path to our modified model (i.e., Model A). Additional modification indices that were consistent with the previous literature and were thus included in Model A were (a) a path from autonomy discrepancies to depressive symptoms, and (b) a path from acculturation dissonance to depressive symptoms. In addition, the interaction term between mother-daughter conflict and maternal supportive parenting contributed significantly to model misfit and model non-convergence was thus removed from the model.

Table 2.

Standardized parameter estimates (and standard errors) with corresponding model fit statistics for all models compared.

| Model 0 | Model A | Model A1 | Model B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimated | Initial unconstrained |

Modified unconstrained |

Fully Constrainedad |

With constrained & unconstrained paths |

| Early Adolescents (7th Grade) | ||||

| Mother’s age →depressive symptoms | −.12 (.01) | −.10 (.01) | −.11 (.01)† | −.11(.01) |

| Mother education →depressive symptoms | .04 (.01) | .01 (.02) | .02 (.01) | .02 (.01) |

| Mother’s nativity →depressive symptoms | −.14 (.14) | −.15 (.16) | −.07 (.12) | −.11(.14) |

| Daughter’s nativity →depressive symptoms | .15 (.09)† | .14 (.09)† | .07 (.07) | .15 (.09)† |

| Family Structure →depressive symptoms | −.01 (.03) | −.04 (.08) | −.01 (.02) | −.04 (.03) |

| Puberty →depressive symptoms | −.03 (.08) | −.05 (.08) | −.07 (.06) | .00 (.00)cd |

| Autonomy discrepancy →depressive symptoms |

.00b | .14 (.08)† | .15 (.05)* | .14 (.08)† |

| Acculturation dissonance →depressive symptoms |

.00b | −.06 (.08) | −.05 (.05) | .00 (.00)cd |

| Maternal supportive parenting →depressive symptoms |

−.26 (.07)** | −.22 (.06)** | −.19 (.04)** | −.22 (.06)** |

| Mother-child conflict →depressive symptoms |

.46 (.16)* | .37 (.06)*** | .32 (.05)*** | .32 (.04)d*** |

| Conflict X Supportive Parenting →depressivesymptoms |

−.07 (.06) | .00b | .00b | .00b |

| Mother’s age →conflict | −.07 (.01) | −.02 (.01) | .03 (.01) | −.00 (.01) |

| Mother education → conflict | −.03 (.02) | .00 (.02) | −.00 (.01) | −.01 (.02) |

| Mother’s nativity → conflict | .17 (.25) | .16 (.23) | .15 (.16)* | .15 (.21)† |

| Daughter’s nativity → conflict | .02 (.15) | −.04 (.14) | .01 (.09) | −.05 (.14) |

| Family Structure → conflict | .01 (.04) | .05 (.04) | −.01 (.02) | .04 (.04) |

| Puberty → conflict | .17 (.12)* | .09 (.12) | .11 (.09)† | .00 (.00)cd |

| Autonomy discrepancy → conflict | .05 (.06) | .17 (.11)* | .13 (.08)* | .15 (.11)* |

| Acculturation dissonance → conflict | .07 (.12) | .03 (.11) | .09 (.07) | .00 (.00)c |

| Maternal supportive parenting →conflict | .00b | −.30 (.09)*** | −.33 (.03)*** | −.37 (.05)d*** |

| Autonomy X acculturation →conflict | .06 (.18) | .08 (.17) | .07 (.11) | .00 (.00)cd |

| Puberty →autonomy discrepancy | .18 (.09)* | .18 (.09)* | −.07 (.02)** | .18 (.09)* |

| Middle Adolescence (10th Grade) | ||||

| Mother’s age →depressive symptoms | −.12 (.01) | −.12 (.01) | −.08 (.01)† | −.11 (.01) |

| Mother education →depressive symptoms | .06 (.02) | .06 (.02) | .01 (.01) | .04 (.02) |

| Mother’s nativity →depressive symptoms | .03 (.17) | .05 (.19) | −.05 (.12) | .06 (.17) |

| Daughter’s nativity →depressive symptoms | −.01 (.10) | −.01 (.10) | .07 (.07) | −.02 (.10) |

| Family Structure →depressive symptoms | .03 (.03) | .02 (.03) | −.01 (.02) | .03 (.03) |

| Puberty →depressive symptoms | −.12 (.11) | −.12 (.11) | −.05 (.06) | .00 (.00)cd |

| Autonomy discrepancy →depressive symptoms |

.00b | .13 (.09) | .12 (.06)* | .12 (.09) |

| Acculturation dissonance →depressive symptoms |

.00b | −.01 (.07) | −.05 (.05) | .00 (.00)cd |

| Maternal supportive parenting →depressive symptoms |

−.19 (.08)† | −.13 (.07) | −.18 (.04)** | −.11 (.06) |

| Mother-child conflict →depressive symptoms |

.34 (.17)† | .24 (.07)** | .27 (.05)*** | .28 (.05)d*** |

| Conflict X Supportive Parenting →depressive symptoms |

−.09 (.07) | .00b | .00b | .00b |

| Mother’s age →conflict | .19 (.01) | .10 (.01) | .03 (.01) | .10 (.01) |

| Mother education → conflict | −.05 (.02) | −.03 (.02) | −.00 (.01) | −.02 (.02) |

| Mother’s nativity → conflict | .07 (.26) | .10 (.23) | .14 (.16)* | .13 (.22) |

| Daughter’s nativity → conflict | .00 (.12) | .04 (.11) | .01 (.09) | .04 (.11) |

| Family Structure → conflict | −.03 (.04) | −.07 (.03) | −.01 (.03) | −.07 (.04) |

| Puberty → conflict | .12 (.14) | .11 (.13) | .09 (.07)† | .00 (.00)cd |

| Autonomy discrepancy → conflict | .12 (.06)* | .07 (.11) | .12 (.07)* | .00 (.00)c |

| Acculturation dissonance → conflict | .15 (.09) | .14 (.08) | .10 (.07) | .18 (.08)* |

| Maternal supportive parenting →conflict | .00b | −.42 (.07)*** | −.39 (.05)*** | −.42 (.07)d*** |

| Autonomy X acculturation →conflict | .14 (.16) | .10 (.15) | .08 (.11) | .00 (.00)cd |

| Puberty →autonomy discrepancy | −.00 (.10) | −.00 (.10) | −.07 (.02)** | .00 (.00)c |

| Fit Indices | ||||

| χ2 | 78.45 | 17.46 | 81.21 | 29.78 |

| df | 14 | 12 | 51 | 25 |

| RMSEA | .18 | .06 | .07 | .04 |

| CFI | .90 | .96 | .79 | .97 |

| TLI | .54 | .81 | .75 | .92 |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

direct effect parameters, covariances, and means were constrained across groups and variances were not constrained across, unstandardized parameters t-values were the same in the Mplus printout, however standardized values may be different across groups.

path was not estimated in the corresponding model.

path constrained to zero.

equality constraint across groups

Modified Unconstrained Model (Model A)

Model A demonstrated a significant improvement in fit over the initial unconstrained model (Δχ2 (2) = 66.99, p < .001; see Table 2). The following relations were significant in the modified unconstrained model: (a) maternal supportive parenting was negatively related to mother-daughter conflict for early and middle adolescents and negatively related to depressive symptoms for early adolescents, (b) mother-daughter conflict was positively related to depressive symptoms for early and middle adolescents, and (c) autonomy expectation discrepancy was positively related to mother-daughter conflict for early adolescents. No control variables were significantly related to depressive symptoms or mother-daughter conflict.

Multiple Group Analyses: Examining Differences Between Early and Middle Adolescents

Following procedures for multiple group analyses in path models described above, our next step was to compare Model A, which was freely estimated (i.e., unconstrained), to Model A1, which was a fully constrained version of Model A. Using the χ2 difference test, results indicated that the fit of Model A1, which required all paths to be equal for early and middle adolescents, was significantly different from the fit of Model A (Δχ2 (39) = 63.75, p < .01). Examination of fit indices for Model A1 indicated that this fully constrained model did not fit the data well (e.g., CFI below .90; see Table 2), indicating that there were significant differences between early adolescents and middle adolescents with respect to paths being estimated in the model (i.e., paths should not be constrained to be equal across developmental groups). To identify which paths were significantly different between groups, we followed a sequential process whereby we constrained specific paths to be equal and compared the fit of the more constrained model to Model A. For example, if a path was significant for both early and middle adolescents, this path was constrained to be equal across groups, and this constrained model was compared to Model A to determine if this change contributed to model misfit. In addition, path coefficients that were statistically significant only for early adolescents were freely estimated for early adolescents and set to zero for middle adolescents and vice versa (Byrne, 2001); the revised model was then compared to Model A. Additionally, paths that were found to be non-significant for both early and middle adolescents (e.g., pubertal development to depressive symptoms) were set to zero for both groups.

Final Model (Model B)

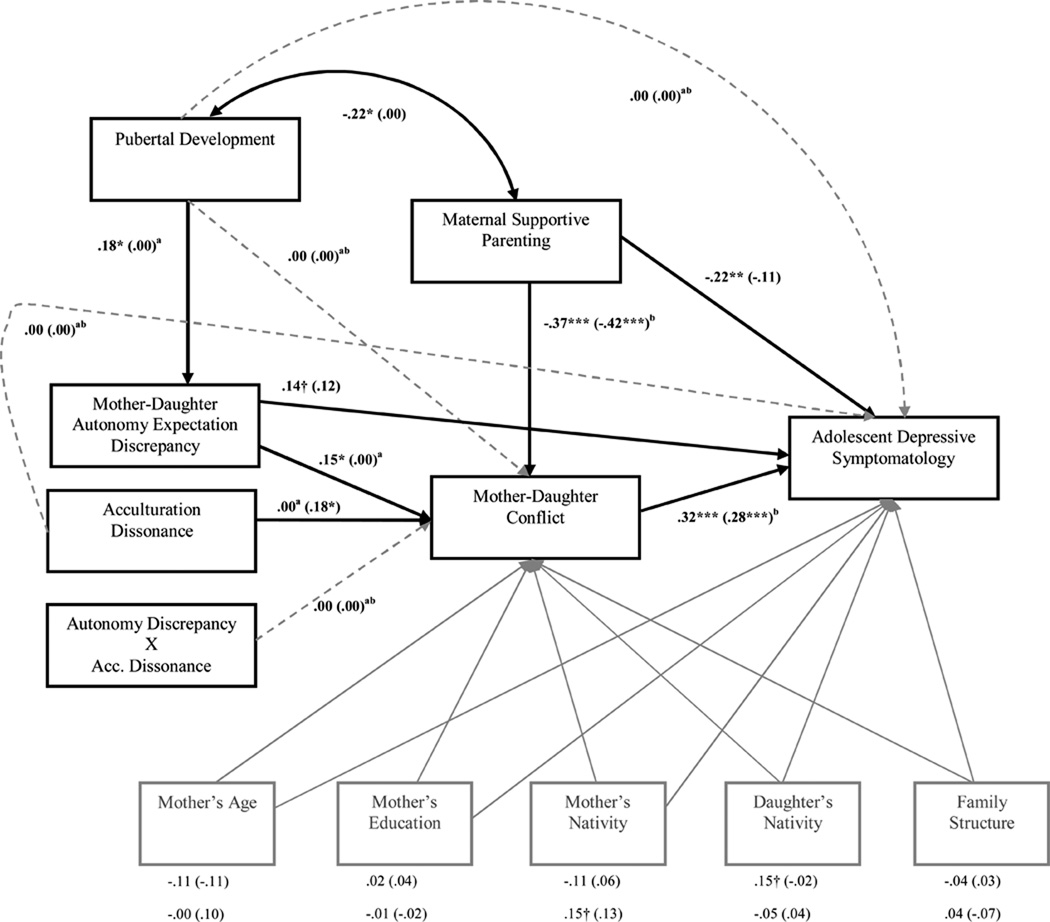

The final model (i.e., Model B), in which some paths were equivalent across groups and some were allowed to be freely estimated, yielded an adequate fit to the data and fit indices were somewhat better than fit indices for Model A (e.g., Model B had a lower RMSEA value, a higher CFI, and a higher TLI, when compared to Model A). The χ2 difference test comparing Model B to Model A (i.e., fully unconstrained) indicated that the models did not differ significantly from each other (Δχ2 (13) = 12.32, ns). In this case, the nonsignificant χ2 difference indicated that the additional constraints imposed in Model B did not contribute to model misfit. Furthermore, because Model B included some equality constraints and, thus, estimated fewer parameters, it was the more parsimonious model (Kline, 1998). This, combined with the better fit indices led to our decision to adopt Model B as the final model (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Final Model Predicting Mexican-origin Early and Middle Adolescents’ Depressive Symptoms.

Note. Standardized estimates presented for early and (middle) adolescents. Control variables are in grey, the first row of values under control variables presents the direct effects to adolescent depressive symptoms and the second row presents the direct effects to mother-daughter conflict.

†p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

aparameter value fixed to zero.

bparameter constrained to be equal across groups.

The results from Model B provided partial support for our hypotheses. Specifically, among early adolescents, autonomy expectation discrepancy scores were positively associated with mother-daughter conflict, and conflict was positively associated with depressive symptoms. In addition, pubertal development was positively associated with mother-daughter autonomy discrepancy scores. Finally, there was a trend indicating that mother-daughter autonomy discrepancy scores were positively associated with early adolescents’ depressive symptoms. This model explained 3% of the variance in autonomy expectancy discrepancies, 21% of the variance in mother-daughter conflict and 31% of the variance in depressive symptoms among early adolescents.

For middle adolescents, mother-daughter acculturation dissonance was positively associated with mother-daughter conflict, and conflict was positively associated with depressive symptoms. Pubertal development was not a significant predictor of any constructs for middle adolescents. Finally, for both early and middle adolescents, maternal supportive parenting was negatively associated with mother daughter conflict; it was only for early adolescents, however, that supportive parenting was negatively associated with adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Contrary to our expectations, neither acculturation dissonance nor maternal supportive parenting significantly moderated any of the hypothesized associations. The model explained 0% of the variance in autonomy expectancy discrepancies, 22% of the variance in mother-daughter conflict and 15% of the variance in depressive symptoms among middle adolescents.

In sum, four paths were determined to be significantly different across early and middle adolescents. Specifically, the paths from (1) pubertal development to autonomy expectation discrepancies, (2) autonomy expectation discrepancies to mother-daughter conflict, (3) maternal support to depressive symptoms, and (4) acculturation dissonance to mother-daughter conflict were found to be statistically different between groups.

Examining Indirect Effects

Given that the paths from maternal supportive parenting to mother-daughter conflict and from mother-daughter conflict to depressive symptoms were statistically significant for both groups, as well as the paths from autonomy discrepancies to mother-daughter conflict for early adolescents and from acculturation dissonance to mother-daughter conflict for middle adolescents, the indirect effects of these constructs on depressive symptoms via mother-daughter conflict was explored. Additionally, because the path from pubertal development to autonomy discrepancies and from autonomy discrepancies to mother-daughter conflict was significant for early adolescents as well, this indirect effect was also tested. Table 3 shows the estimates for the indirect effects and their bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals. MacKinnon and colleagues’ (MacKinnon, Lockwood, &Williams, 2004) recommended distribution of product method (i.e., bootstrapping) was employed to test for mediation given that this method has more accurate Type I error rates and more statistical power than other approaches to test for mediation (MacKinnon, 2008). Using the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals, findings indicated that the indirect effect from maternal supportive parenting to depressive symptoms via mother-daughter conflict was statistically significant for early adolescents (indirect effect = −.09, 95% CI = −.22, −.05) and middle adolescents (indirect effect = −.09, 95% CI = −.21, −.05). The negative value of the effect indicates that increases in maternal supportive parenting significantly contributed to decreases in depressive symptoms via its association with mother-daughter conflict. In total, 35% of the effect of maternal supportive parenting on depressive symptoms was mediated by mother-daughter conflict for the early adolescent sample [−.37*.32/(−.222 + (−.37*.32))= .35] (see MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995) and 52% of the effect was mediated by mother-daughter conflict for the middle adolescent sample [−.42*.28/(−.11 + (−.42*.28)) = .52]. No other indirect effects were significant.

Table 3.

Bootstrapped estimates of indirect effects with bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI)

| Bias-Corrected 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | Point Estimate |

SE | Lower | Upper |

| Early Adolescents | ||||

| Supportive parenting →conflict → depressive symptoms |

−.09 | .02 | −.22 | −.05 |

| Autonomy →conflict → depressive symptoms | .05 | .03 | −.03 | .15 |

| Puberty →autonomy discrepancy → conflict | .04 | .03 | −.01 | .10 |

| Middle Adolescents | ||||

| Supportive parenting →conflict → depressive symptoms |

−.09 | .02 | −.21 | −.05 |

| Acculturation →conflict → depressive symptoms |

.04 | .02 | −.01 | .13 |

Note: 5000 bootstrap samples.

Discussion

We took a developmental-contextual approach to examine developmental, relational, and cultural factors linked to the depressive symptomatology among a sample of early and middle adolescent Mexican-origin females. After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, our findings provide a more nuanced understanding of the interplay among pubertal development, autonomy expectation discrepancies, acculturation dissonance, mother-daughter conflict, maternal support, and Mexican-origin female adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Furthermore, our findings point to important similarities, and differences, across developmental period studied and suggest important directions for future research.

Differences Across Developmental Periods

Pubertal development, autonomy expectation discrepancies, and mother-daughter conflict

When testing the overall model, pubertal development was not directly related to depressive symptomatology. However, pubertal development was positively associated to mother-daughter autonomy expectation discrepancies among early adolescents, not middle adolescents. These findings contradict previous work linking pubertal development directly to depressive symptoms. Further, they suggest that at least for early adolescents, in the presence of developmental and relational domains, pubertal development is significantly related to developmental issues such as autonomy discrepancies, rather than directly associated to depressive symptoms. Pubertal development may play an important role in these processes among early adolescents, and not middle adolescents, because of relatively more intense parent-adolescent relationships among families with early maturing girls, given parents’ increased concern for daughters who seem too young to be developing (Granic et al., 2003). Given our findings, it will be informative for future research to examine the role of pubertal development on adjustment by taking into account both developmental and relational processes. With respect to autonomy, our findings, similar to those of Holmbeck and O’Donnell (1991), suggest that it is not autonomy expectations per se that are related to parent adolescent conflict, but rather the differing expectations that parents and adolescents have on autonomy that are related to conflict. In fact, previous work has typically examined the association between adolescents’ behavioral autonomy expectations (not the discrepancy) and parent-adolescent conflict and found no significant association (e.g., Fuligni, 1998; Zhang & Fuligni, 2006). Our findings extend this literature by identifying differences across developmental periods with respect to the contribution of autonomy expectation discrepancies on conflict and depressive symptoms. In this study, pubertal development predicted autonomy expectation discrepancies, which predicted parent-adolescent conflict and this, in turn, predicted depressive symptoms, but only for early adolescents.

Interestingly, although conflict is expected to decrease as adolescents get older (Bakken & Brown, 2010), early and middle adolescents in this study reported similar levels of conflict and discrepancy values on autonomy expectations (see Table 1). Perhaps autonomy expectation discrepancies did not predict mother-daughter conflict among middle adolescents because previous exposure to conflict over key behaviors, as well as a greater ability to resolve conflict (perhaps because of increased social and cognitive maturity), may reduce the impact that key issues have on experiencing conflict over time (Bakken & Brown, 2010). Also, as youth move into mid-adolescence, they use tactics such as strategically disclosing information to their parents, withholding information, and lying that can limit or avoid conflict altogether (Bakken & Brown, 2010). Consequently, it is possible that autonomy expectation discrepancies did not predict conflict among middle adolescents because of developmentally linked strategies that adolescents might have used to avoid conflict. This is supported by previous work (Collins et al., 1997) in which 13–15 year-olds were more likely than 10–12 year-olds to engage in activities (e.g., spend time with friends) without their mothers’ knowledge. Similarly, work by Gallegos-Castillo (2006) supports this idea. Gallegos-Castillo described how a 15-year old Mexican-origin adolescent concealed information from her parents in order to experience freedom in her daily activities. Instead of telling her parents that her summer job had ended, she decided to continue her routine and leave home to go “to work” because she knew her parents would not let her go out if they knew she did not have to go to work. This strategy allowed this adolescent to engage in activities without her parents’ knowledge and probably limited the opportunity for conflict to occur. Thus, discrepancies in autonomy expectations may not directly correspond with the frequency of conflict experienced for middle adolescents because they may find covert ways (e.g., lying to parents) to engage in activities about which they and their parents do not agree.

Acculturation dissonance, parent-adolescent conflict, and mother-daughter conflict

We found partial support for the acculturation-gap distress hypothesis. Specifically, mother-daughter acculturation dissonance was positively associated with mother-daughter conflict, but only for middle adolescents, not early adolescents. Specifically, greater acculturation dissonance between mothers and daughters predicted more conflict in the dyad. These findings suggest that cultural issues contribute to mother-daughter conflict for middle adolescents whereas developmental issues such as discrepancies in autonomy expectations contribute to conflict among early adolescents. As stated earlier, it is possible that by middle adolescence autonomy issues are dealt with differently (e.g., by concealing information from parents about adolescents’ activities); therefore, not predicting conflict. On the other hand, cultural issues, likely to have been present since early adolescence, may become more salient during middle adolescence due to adolescents’ increasing cognitive capacities that may give way to challenging parents’ cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors, leading to more conflict.

It is important to note, however, that the lack of significant findings for early adolescents and the inability to find a moderating effect for mother-daughter acculturation dissonance may have resulted from assessing acculturation dissonance only. Cultural orientation is multidimensional in nature, which not only includes adherence and adaptation to the mainstream culture (i.e., acculturation), but also adherence to the ethnic culture (i.e., enculturation; Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sorolli, 2002). Although the acculturation gap distress hypothesis emphasizes the detrimental role of experiencing cultural dissonance with the mainstream culture, previous studies suggest that enculturation dissonance may play a more critical role than acculturation dissonance in the lives of ethnic minority youth (Costigan & Dokis, 2006; Phinney & Vedder, 2006). For instance, Phinney and Vedder found that greater intergenerational discrepancies in enculturation values (i.e., family obligations) were associated with poorer adjustment and adaptation for both immigrant and native-born adolescents; whereas, discrepancy scores on mainstream values were not found to be significant predictors of adjustment and adaptation. It is possible that adolescents’ relatively lower adherence to enculturation values (e.g., respect for authority or family obligations) may be perceived by parents as a sign of their children’s rejection of the native culture and, thus, cause more friction than discrepancies between parents and children on mainstream values. Further, the lack of significant findings with respect to acculturation dissonance may have been due to the fact that our study examined acculturation processes contextually. Gonzales et al. (2002) noted that to have a complete understanding of the impact of acculturation on mental health outcomes, a full examination of the social system in which adolescents are embedded is warranted. Thus, it is possible that the non-significant findings were due to the fact that developmental and relational factors salient during adolescence played a greater role in Mexican-origin adolescents’ mental health than acculturation dissonance. This resonates with scholars’ observations that perhaps previous studies “have too often used acculturation to account for psychological maladaptation among adolescents with immigrant backgrounds when these problems may possibly be part of normal developmental process[es] all adolescents undergo” (Sam & Virta, 2003, pp. 226–227). Future research is warranted to examine cultural dissonance in tandem with more proximal developmental and contextual factors to have a better understanding of the role of family cultural orientation on the adjustment of Latino youth.

Similarities Across Developmental Periods: Maternal Supportive Parenting and Mother-Daughter Conflict

Importantly, we also found some associations that were consistent across developmental periods, such as the association between maternal supportive parenting and adolescents’ depressive symptoms being mediated by mother-daughter conflict. Our findings provide support for the idea that the emotional context of what parents do matters across adolescence (Steinberg, 2001). That is, not only did frequency of mother-daughter conflict predict depressive symptoms, but the emotional support adolescents perceived from their mothers did as well. Interestingly, for middle adolescents, maternal support was not directly related to depressive symptoms, but only indirectly via mother-daughter conflict. Although we expected maternal supportive parenting to moderate the association between mother-daughter conflict and depressive symptoms, our analyses indicated that maternal supportive parenting was not a moderator but rather a direct and indirect (via mother-daughter conflict) predictor of depressive symptoms for early and middle adolescents. Previous studies with Mexican-origin adolescents have found support to be a direct predictor of depressive symptoms (e.g., Benjet & Hernandez-Guzman, 2001; Dumka, Roosa & Jackson, 1997); our findings extend this work by identifying mother-daughter conflict as a significant mediator of this link. Specifically, lower levels of maternal supportive parenting predicted greater frequency of conflict, which predicted greater depressive symptoms. Although theoretical work (i.e., Montemayor, 1986) has linked parent-adolescent conflict to the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship (e.g., negative parenting, supportive parenting), limited work exists that has examined this association (e.g., Barber; 1994). Barber (1994) examined predictors of parent-adolescent conflict in families with an adolescent and found that negative parenting (e.g., yelling, spanking) was a predictor of conflict for Black, White, and Hispanic families. Thus, Barber’s findings provide some support for the link between parent-adolescent relationship quality and parent-adolescent conflict.

Together, previous studies have found links between support and conflict, and between support and depressive symptoms; however, the current study examined these constructs simultaneously and was able to identify a significant meditational process. More research is needed that examines the paths by which parent-adolescent relationship quality domains are related to adjustment. In general, support for the beneficial effects of supportive parenting and other parenting domains (e.g., acceptance, consistency discipline) has emerged from literature that has employed direct- or main-effects models (Wolchik et al., 2000). However, parent-adolescent relationship factors can be thought of as direct, indirect, mediating, or moderating factors depending on the research question and the theory being tested (Frazier, Tix, and Barron, 2004). Future research would benefit from concurrently examining direct, indirect, and buffering effects to have a better understanding of the instances in which the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship may mediate, moderate, and/or directly/indirectly predict adolescents’ adaptation and adjustment.

Limitations and Future Directions

A few caveats are worth mentioning. First, participants in this study were recruited from a geographical area with a substantial Latino population of Mexican origin. Thus, the generalizability of these findings to Mexican-origin adolescents residing in areas with a less prominent Mexican-origin population, or to other Latino groups, is unknown. For instance, in a predominately European American community, Mexican-origin adolescents may compare their experiences to those of their European American peers, who may be allowed more autonomy at an earlier age. As a result, the discrepancy between parents’ views and adolescents’ views in Mexican-origin families may be more salient due to social comparisons with non-Latino White peers. Furthermore, Mexican-origin youth may model the behaviors of their non-Mexican peers (e.g., expressing their disagreement with parents’ views), which may result in the discrepancies between parents’ and adolescents’ acculturation and autonomy expectations more salient and, perhaps increasing the likelihood of parent-adolescent conflict. Future work should consider this important contextual feature.

Second, in terms of measurement, our measure of cultural orientation was narrowly defined as language acculturation. We did not assess other aspects of acculturation such as beliefs and values. It is possible that including other domains of acculturation would have revealed different findings. Third, although the hypothesized associations were theoretically derived and based on existing empirical work, the current study used a cross-sectional design, which limited the ability to draw inferences regarding the direction of effects. However, one possibility is that the relation between parent-adolescent relationship factors and depressive symptoms is bidirectional. That is, depressive symptomatology may result in changes in the parent-adolescent relationship. This is in line with the ideas of social interaction theory (Coyne, 1976), which posits that negative behaviors exhibited by depressed individuals (e.g., negative self-statements and complaining) may lead to rejection and avoidance from those around, resulting in less support and distant relationships (Pineda, Cole, & Bruce, 2007). Thus, the behaviors elicited by a depressed adolescent may lead to changes in the parent-adolescent relationship such as decreasing levels of support and increasing levels of conflict from parents, which in turn can contribute to the maintenance of future depressive behaviors (Pineda, Cole, & Bruce, 2007). Longitudinal designs should be implemented to better understand the directional nature of these associations. We also were limited to examining adolescents’ relationships with their mothers. Few studies have focused on Latino fathers and how father-child relationship factors affect youth’s well-being (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth, & Lamb, 2000; Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2001). It is possible that conflict with fathers may be particularly influential for Latina’s well-being during adolescence – a time when fathers may increasingly be called upon by mothers to handle autonomy issues that emerge such as whether girls can go out on dates.

Despite the noted limitations, the multiple informant design of the current study, utilizing reports from both mothers and adolescents to assess discrepancies in the mother-daughter relations is a significant strength and provides important observations for future research. Furthermore, the developmental-contextual approach of the current study is consistent with scholars’ recommendations to study the interactive nature of biological, psychological, cognitive, relational, and contextual factors and how they inform adolescent depression (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998). There is limited work that has utilized such an approach to understand the precursors of Latino adolescents’ depressive symptoms and, instead, studies have focused largely on culture-related factors as sole predictors. The current study provides an initial step in this important direction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an R36MH077425 dissertation grant from the National Institute of Mental Health and a research grant from the Graduate and Professional Student Association at Arizona State University awarded to the first author. The authors wish to thank their undergraduate research assistants for their assistance in conducting this investigation, and the adolescents and mothers for their participation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/dev

References

- Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Kuperminc GP, Jodl K. Stability and change in attachment security across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75(6):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16(5):427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala J. Confianza, consejos, and contradicciones: gender and sexuality lessons between Latina adolescent daughters and mothers. In: Denner J, Guzman BL, editors. Latina girls: Voices of adolescent strengths in the United States. NY: New York University Press; 2006. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current trends and future directions. Westport, Ct: Praeger; 2000. pp. 77–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken JP, Brown BB. Adolescent secretive behavior: African American and Hmong adolescents’ strategies and justifications for managing parents’ knowledge about peers. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(2):359–388. [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste DA. Immigrant families, adolescents, and acculturation: Insights for therapists. Marriage and Family Review. 1993;19:341–363. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Cultural, family, and personal contexts of parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(2):375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Hernandez-Guzman L. Gender differences in psychological well-being of Mexican early adolescents. Adolescence. 2001;36(141):47–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D. Measurement of the "acculturation gap" in immigrant families and implications for parent-child relationships. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent child relationships: Measurement and development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, Gargiulo J. Validity of self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child Development. 1987;58(3):829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buriel R, De Ment T. Immigration and sociocultural change in Mexican, Chinese, and Vietnamese American families. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Landale N, editors. Immigration and the family: Research and policy in U.S. immigrants. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 165–200. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25(2):127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Tamis-LeMonda C, Bradley R, Hofferth, Lamb M. Fatherhood in the 21st century. Child Development. 2000;71(1):127–136. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Examining goodness-of-fit indices for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth S. The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):221–241. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. Shared views and parent-adolescent relationships. In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum; 1991. pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Laursen B, Mortensen N, Luebker C, Ferreira M. Conflict processes and transitions in parent and peer relationships: Implications for autonomy and regulation. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12(2):178–198. doi: 10.1177/0743554897122003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AW, Luebker C. Parent and adolescent expectancies: Individual and relational significance. In: Smetana JG, editor. Beliefs about parenting: Origins and developmental implications. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994. pp. 65–80. New Directions for Child Development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Ey S, Grant KE. Taxonomy, assessment, and diagnosis of depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(2):323–344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Dokis DP. Relations between parent-child acculturation differences and adjustment within Chinese families. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1252–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85(2):186–196. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean H. Conflict in the Latino parent-youth dyad: The role of emotional support from the opposite parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(3):484–493. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa M, Vega R, Radisch M. The role of acculturation in the substance abuse behavior of African-American and Latino adolescents: Advances, issues, and recommendations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(1):33–42. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka L, Roosa MW, Jackson KM. Risk, conflict, mothers’ parenting and children’s adjustment in low-income, Mexican Immigrant, and Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59(2):309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Narang SK, Bhadha BR. East meets West: Ethnic identity, acculturation, and conflict in Asian Indian families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(3):338–350. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SS, Quatman T. Factors influencing age expectations for adolescents’ autonomy: A study of Early Adolescents and Parents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1988;8(4):323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Tix A, Barron K. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51(1):115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(4):782–792. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos-Castillo A. La casa: Negotiating family cultural practices, constructing identities. In: Denner J, Guzman BL, editors. Latina girls: Voices of adolescent strengths in the United States. NY: New York University Press; 2006. pp. 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CG, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Vasquez García H. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Preto N. Latino families: An overview. In: McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Garcia-Preto N, editors. Ethnicity and family therapy. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Elder GH, Jr, Regnerus M, Cox C. Pubertal transitions, perceptions of being overweight, and adolescents’ psychological maladjustment: Gender and Ethnic differences. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2001;64:363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales N, Deardorff J, Formoso D, Barr A, Barrera M., Jr Family mediators of the relation between acculturation and adolescent mental health. Family Relations. 2006;55:318–330. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez A, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Pitts SC, Hill NE, Roosa MW. A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multi-ethnic low-income sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(3):365–379. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Dishion TJ, Hollenstein T. The family ecology of adolescence: A dynamic systems perspective on normative development. In: Adams G, Berzonsky M, editors. Handbook of Adolescence. New York: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 60–91. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(4):707–716. [Google Scholar]