Abstract

Aim

This paper is a report of an analysis of the concept of connectedness.

Background

Previous attempts to conceptualize patient–provider relationships were limited in explaining how such relationships are fostered and maintained, and how they influence patient outcomes. Connectedness is a concept that may provide insights into the advantages of patient–provider relationships; however, the usefulness of this concept in health care is limited by its conceptual ambiguity. Although connectedness is widely used to describe other social relationships, little consistency exists among its definitions and measures.

Data Sources

Sources identified through CINAHL, OVID, PubMed, and PsychINFO databases, as well as references lists of selected articles, between 1983 and 2010.

Review Methods

A hybrid concept analysis approach was used, involving a combination of traditional concept analysis strategies that included: describing historical conceptualizations, identifying attributes, critiquing existing definitions, examining boundaries, and identifying antecedents and consequences.

Results

Using five distinct historical perspectives, seven attributes of connectedness were identified: intimacy, sense of belonging, caring, empathy, respect, trust, and reciprocity. A broad definition of connectedness, which can be used in the context of patient–provider relationships, was developed. A preliminary theoretical framework of connectedness was derived from the identified antecedents, attributes, and consequences.

Conclusion

Research efforts to advance the concept of connectedness in patient–provider relationships have been hampered by a lack of conceptual clarity. This concept analysis offers a clearer understanding of connectedness, provides recommendations for future research, and suggests practice implications.

Keywords: concept analysis, connectedness, patient–provider relationships

INTRODUCTION

Connectedness is a concept that, when more fully understood in the context of patient–provider relationships, has the potential to improve patient health outcomes (Suchman & Matthews 1988, McManus 2002, Thorne et al. 2005, Atlas et al. 2009). Connectedness is broadly defined as the extent to which a person perceives that he/she has a “significant, shared, and meaningful personal relationship with another person, a spiritual being, nature or an aspect of one’s inner self” (Haase et al. 1992, p. 146). Researchers have found that patients’ perceptions of the extent of their connectedness or the quality of the relationship with their healthcare providers is associated with increased participation in medical decision-making (Cooper-Patrick et al. 1997, Leidy & Haase 1999, Marelich & Murphy 2003), adherence to treatment (Schneider et al. 2004, van Servellen & Lombardi 2005, Beach et al. 2006b), and decreased risk-taking behaviors (Ettner 1999, Beach et al. 2006b).

Although many researchers have used the term “connectedness” to describe and/or measure a person’s perception of having a significant relationship with other people, there is little consistency across the literature in the definition or measurement of connectedness. Additionally, little research has been done to clarify the concept of connectedness within the context of patient–provider relationships. The purpose of this article is to clarify the concept of connectedness by evaluating how it has been examined in social relationships.

BACKGROUND

Historically, researchers, theorists and clinicians have used a variety of terms to describe the relationships between patients and providers, including patient-centered care (Mead & Bower 2000, Mallinger et al. 2005), relationship-centered care (Beach et al. 2006a, Suchman 2006); perceived social support from healthcare providers (Brucker & McKenry 2004, Arora et al. 2007), and therapeutic alliance (Summers & Barber 2003, Hilsenroth et al. 2004). Attempts to clearly conceptualize these relationships, the mechanisms by which they are developed or maintained, and their influence on patient health outcomes have thus far been limited. Of most concern is the fact that the research on these concepts tends to focus on relationships from a healthcare provider’s perspective; the patient’s experience and perceived meaning relative to having a relationship with providers are inadequately described (Epstein et al. 2005, Thorne et al. 2005).

Method of analysis

To clarify the concept of connectedness, we used a hybrid concept analysis approach similar to that used by Haase et al. (2009) to clarify resilience. The clarification process incorporated traditional concept analysis strategies proposed by Rodgers (2000), Walker and Avant (2004), and Hinds (1984), including: (1) describing how connectedness was historically conceptualized, (2) identifying essential attributes, (3) critiquing existing definitions, (4) examining boundaries, and (5) identifying antecedents and consequences.

DATA SOURCES

Literature selected for this analysis was located through database search engines (CINAHL, OVID, PubMed, and PsychINFO), for the period 1983–2010, using the keyword connectedness. Database searches were limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English. Since a very large number of articles (over 2000) were retrieved using the keyword “connectedness,” the search was limited to articles using that term in the title. After deleting duplicates, abstracts of the 204 remaining articles were read. Articles that did not pertain to social relationships (i.e., connectedness to oneself, nature, the Internet, marketing ads, political media, and television characters) were excluded. This criterion also eliminated articles that described connectedness as a method of image segmentation (i.e., fuzzy connectedness), genetic scheme referencing in animal breeding, and perceptual organization (i.e., uniform connectedness).

Based on the selection criteria, a total of 139 articles remained. Since the abstracts provided little information about definitions or assumptions used, the 139 selected articles were read in closer detail, focusing on definitions, assumptions, attributes, antecedents, and consequences of connectedness. Articles with no definitions of or assumptions about connectedness were excluded. Articles that referenced a classic or popular definition of connectedness related to a program of research (e.g., Grotevant & Cooper 1986, Gavazzi & Sabatelli 1990, Resnick et al. 1993, Lee & Robbins 1998, Karcher & Lee 2002) were limited to the original and/or most recent publication. Articles that referenced these classics, but did not provide additional rich descriptions of connectedness, were omitted. Reference lists from the selected articles were also examined for other relevant articles or book chapters. A total of 23 research articles, four review articles, and one book chapter were identified. These key literature sources were then reread, and essential information related to connectedness was extracted.

RESULTS

Connectedness was examined by researchers from a variety of academic disciplines including child and adolescent development, education, medicine, nursing, psychology, and public health. Connectedness was studied across the lifespan from early childhood (Clark & Ladd 2000) to older adults (Leidy & Haase 1999, Ong & Allaire 2005). The most common population in which connectedness was studied was adolescents.

Historical perspectives on connectedness

Five different perspectives on connectedness were found. Within and across these perspectives, researchers conceptualized connectedness as a(n): (1) component of the individuation process; (2) condition of the social environment; (3) culturally influenced conception of self; (4) personality trait; and (5) affective quality of positive social interactions with significant others.

Component of the individuation process

The earliest conceptualization of connectedness in the literature set seems to have emerged from research in which authors presented connectedness as having a positive or negative impact on individuation. For example, Grotevant and Cooper (1986) conceptualized connectedness as communicative processes (i.e., openness and respect for the views of others) among family members that promoted the psychosocial development of adolescents. Clark and Ladd (2000) held a similar view and characterized connectedness as the mutuality of parent–child expression. Among these authors, individuation was seen as positively influenced by a high level of connectedness in parent–child/adolescent relationships and characterized by mutuality between parents and children.

In contrast, Gavazzi and Sabatelli (1990) believed that connectedness was part of the individuation process and characterized it as the extent to which an adolescent is emotionally, financially, and functionally dependent on his/her parents. Well-individuated adolescents were considered to be less dependent on their parents (Gavazzi et al. 1999). In this conceptualization, lower levels of connectedness were perceived as socially desirable, and connectedness that was predicated on mutuality was considered less desirable because authors believed it could hinder individuation and independence from parents. Within perspectives on individuation, it is apparent that there is a disagreement as to what degree of connectedness is healthy versus dependent.

Condition of the social environment

In subsequent research, connectedness was expanded beyond the context of individuation from family and was viewed broadly as a condition influenced by the environment. Barber and Schluterman (2008), for example, described connectedness as the “essence of the social condition” (p. 213). Other scholars perceived connectedness as a consequence of being actively involved with others (Karcher & Lee 2002, Karcher 2005, Ong & Allaire 2005, Townsend & McWhirter 2005, Person et al. 2007) or a therapeutic relationship between patients and their nurse (Heifner 1993, Schubert & Lionberger 1995, Miner-Williams 2007). In each environmental context, connectedness was described as being fostered through supportive interactions and engagement with significant others, and it was believed to be reciprocated among all people involved in the relationship.

Culturally influenced conception of self

Connectedness was also characterized as a culturally influenced construct. For example, some researchers viewed connectedness as an aspect of the collectivism prominent in Eastern cultures (Beyers et al. 2003, Liu et al. 2005, Huiberts et al. 2006). People who were socialized within collectivistic societies or families were said to have a greater tendency to develop a connectedness social orientation. In this perspective, connectedness was described as emotional closeness and interdependence among family members (Liu et al. 2005, Huiberts et al. 2006), as well as “having strong and persuasive emotional ties with parents” (Beyers et al. 2003, p. 352). In Eastern cultures, this type of connectedness was considered a healthy societal norm. In contrast, in Western cultures, individualistic perspectives that promote independence and autonomy are fostered and perceived to be a healthier dynamic within family relationships. These contrasting perspectives indicate that connectedness is influenced by culture.

Personality trait

Another perspective of connectedness emerged from the counseling psychology literature. Within this perspective, connectedness was presented as a personality trait that was developed or underdeveloped over time and integrated into a person’s personality and internal sense of self. For example, Lee and Robbins (1998) characterized social connectedness as “an internal sense of belonging … the subjective awareness of being in close relationship with the social world” (p. 338). These authors viewed social connectedness as a relatively stable psychological sense of how people view themselves in relation to others (Lee & Robbins 1998, Lee et al. 2001). Similarly, Rude and Burnham (1995) perceived connectedness as a part of one’s personality. They described connectedness as a healthy expression of personal inter-dependency (versus neediness, which is problematic) and defined connectedness as “a valuing of relationships and sensitivity to the effects of one’s actions on others” (p. 337). Within this perspective, connectedness was presented as a personality trait that was either strongly developed or remained underdeveloped and that influenced a person's ability to form healthy or unhealthy relationships. Researchers thought that counseling interventions could promote a person’s underdeveloped trait of connectedness.

Affective qualities of positive social interactions with significant others

The most recent and commonly found perspective of connectedness focused on the affective qualities of positive social interactions with significant others (i.e., parents, teachers, and peers). In this perspective, connectedness was defined as a person’s perception of the relationship versus the actual condition or quality of the social relationship. Authors defined connectedness as a person’s perception or belief that he/she is cared for, respected, valued, and understood (Resnick et al. 1993, Resnick et al. 1997, Rew 2002, Edwards et al. 2006, Grossman & Bulle 2006, Shochet et al. 2006, Whitlock 2006, Waters et al. 2009). This perspective predominantly was explored in adolescents. When adolescents indicated that they felt cared for, respected, valued, and understood as a result of connectedness, researchers associated these affective qualities with psychosocial outcomes such as enhanced well-being and fewer risk-taking behaviors (Resnick et al. 1993, Resnick et al. 1997, Shochet et al. 2006).

In summary, the analysis of connectedness revealed five different perspectives. The perspectives were incongruent in how connectedness was defined or conceptualized. However, there were some commonalities across the perspectives in that connectedness was: viewed as an interpersonal phenomenon; related to the ability to form healthy versus maladaptive relationships with others; influenced by culture; and had both environmental and affective components. Although each of these views sheds light on the nature and development of connectedness and some commonalities are present, the literature set exists in disciplinary and/or philosophical “silos,” rendering it less useful for building new knowledge on connectedness. A more cohesive perspective of connectedness may emerge with identification of the essential attributes, antecedents, and outcomes of connectedness found across the literature set.

Attributes

Seven attributes of connectedness were identified: intimacy, sense of belonging, caring, empathy, respect, trust, and reciprocity (see Table 1). These attributes were identified by analyzing the definitions, descriptions of the characteristics of connectedness, and measurement indicators used by the investigators in the reviewed literature. The expression (i.e., the strength or form) of the identified attributes varied across the perspectives; however, all seven attributes were either identified or could be inferred in all instances where connectedness occurred. Although these attributes are discussed separately, it should be noted that they are not mutually exclusive categories; there was a great deal of overlap among the attributes identified.

Table 1.

Attributes of Connectedness

Intimacy

Intimacy was the most common attribute identified within the literature set. This attribute was described as a feeling of closeness or having a unique bond with another person or group of others. This attribute was also described as an observable bond between people that is exhibited by communicative and behavioral expressions of closeness. For example, intimacy in the parent–child/adolescent relationship was defined as the degree to which each other’s feelings and viewpoints were discussed and shared (Clark & Ladd 2000, Grotevant & Cooper 1986, Grotevant & Cooper 1998).

Sense of belonging

A sense of belonging was described as feeling that one fits in with and is part of a group of others. This attribute was identified in studies that examined people’s sense of social connectedness, particularly in adolescents. For example, Shochet et al. (2006) measured adolescents’ sense of connectedness to school by asking questions related to their feeling like a real part of the school and being included in school-related activities.

Empathy

Empathy was another common attribute across the literature set, and was described as an expression of openness and sensitivity to the viewpoints of others or the ability to understand and feel compassionate towards others. For example, children/adolescents and their parents expressed empathy in a connected relationship by being receptive and considerate of one another’s beliefs and values (Clark & Ladd 2000, Grotevant & Cooper 1986, Grotevant & Cooper 1998).

Caring

Caring was an attribute described as being affectionate towards others, experiencing warmth from others, and displaying concern for the well-being of others. For example, a person’s sense of connectedness was commonly measured by how much he or she perceived that significant others (i.e., parents, teachers, peers, etc.) cared about them (Resnick et al. 1993, Resnick et al. 1997, Rew 2002, Grossman & Bulle 2006).

Respect

Respect was described as a sense of being valued and/or displaying value for others. Respect was a particularly common attribute among the studies that explored connectedness between family members, adolescents’ connectedness to school, and nurse–patient connectedness. For example, Miner-Williams (2007) claimed that one of the key elements of connectedness in the nurse–patient relationship was the nurse’s ability to acknowledge the patient as a unique person, which in turn made the patient feel valued by the nurse.

Trust

Trust was a common attribute of connectedness. Trust was described as being able to be open and honest when sharing personal thoughts and feelings with others; having a sense of comfort or safety when interacting with others; or being able to believe in and depend on others. For example, among the authors who perceived connectedness as a culturally influenced construct or a personality trait, trust was exhibited by a person’s confidence in the availability of support from others (Lee & Robbins 1998, Lee et al. 2001, Beyers et al. 2003, Huiberts et al. 2006).

Reciprocity

Reciprocity was an attribute of connectedness exhibited by the mutual exchange of affection and interest that people have in one another. Reciprocity was commonly described in articles that explored connectedness between people (e.g., children and parents; nurses and patients). Reciprocity was also identified in studies that examined persons’ perceptions of connectedness. For instance, Whitlock (2006) found that an adolescent’s sense of connectedness to school is something that is not only received, but also reciprocated (i.e., when an adolescent feels cared for by his/her peers and teachers, the adolescent also cares about those people).

Adequacy of the definitions of connectedness

To further clarify the concept of connectedness, the definitions of connectedness were evaluated for adequacy based on criteria proposed by Cohen and Nagel (1934) and Hamblin (1960) and first described for nursing by Hinds (1984). According to the criteria, definitions: (1) must provide the essential, not accidental attributes; (2) must not directly or indirectly contain the term being defined; (3) should be stated in positive terms; (4) should be expressed in clear or non-figurative language; (5) should reflect a continuum indicating that various amounts of the construct may occur (e.g., uses the words “the degree to which” or “the extent to which”); and (6) indicates the context of the construct (Hinds 1984). A total of 27 definitions were evaluated (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Definitions of Connectedness

| Primary Source (Related Source) |

Definition | Essential attributes are provided |

Term being defined is not re-used |

Stated in positive terms |

Stated in clear, non- figurative language |

Reflects a continuum |

Indicates the context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component of the Individuation Process | |||||||

| Clark & Ladd 2000 | “Connectedness is a feature of the emotional bond formed between the parent and child‥ …we defined connectedness as a dyadic property of the parent-child relationship – as reflected in the mutuality of parent-child emotional expressions” (p. 485). | 1 out 7 | + | + | − | − | + |

| Gavazzi et al. 1999 (Gavazzi & Sabatelli 1990) | Multigenerational interconnectedness refers to the financial, functional, & psychological connections between adolescents/young adults & their families. | ||||||

| Definitions are as follows: | |||||||

| “Financial interconnections refer to the specific monetary ties between family members that reflect the extent to which a person is financially dependent on other family members” (Gavazzi et al. 1999, p. 1361). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | + | + | |

| “Functional interconnections refer to those activities in which family members share time with each other and reflect the extent to which a person is reliant on the family for daily care, companionship, and recreation” (Gavazzi et al. 1999, p. 1361). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | + | + | |

| “Psychological (emotional) interconnections refer to the approval, loyalty, obligation, and guilt that family members experience with one another and reflect the extent to which a person is emotionally dependent on other family members” (Gavazzi et al. 1999, p. 1361). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Grotevant & Copper 1998 (Grotevant & Copper, 1986) | “Connectedness involves processes that link the self to others and has two dimensions: (1) Permeability - expressing responsiveness to the views of others & (2) Mutuality - expressing sensitivity and respect for others” (Grotevant & Copper 1998, p. 4). | 4 out 7 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Condition of the Social Environment | |||||||

| Barber & Schluterman 2008 | Define connection as a “tie between the child and significant other persons (groups or institutions) that provide a sense of belonging, an absence of aloneness, and a perceived bond. Depending on the intimacy of the context, this connection is produced by different levels, degrees or combinations of consistent, positive, predictable, loving, supportive, devoted, and/or affectionate interaction” (p. 213). | 4 out 7 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Karcher 2005 (Karcher & Lee 2002) | “Connectedness reflects youth’s activity with and affection for the people, places and activities within their life” (Karcher 2005, p. 66). | 2 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Heifner 1993 | “A positive connectedness in the psychiatric nurse-pt relationship is a therapeutic state of interaction that enhances the effectiveness of the relationship and benefits the nurse and the patient” (p. 14). | 0 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Miner-Willams 2007 | Connectedness is “the special type of nurse-patient relationship in which the nurse and patient feel a particular closeness [and] is a process of meeting the needs of the spirit” (p. 1230) | 2 out 7 | + | + | − | − | + |

| Ong & Allaire 2005 | Social connectedness defined as “having quality ties with others” (p. 476). | 1 out 7 | + | + | − | − | − |

| Person et al. 2007 | “Social connectedness refers to the relationship that people have with others that results in a sense of belonging, a social identity, support and comfort, a buffer for stressors, and positive influences on coping with psychological and physical problems” (p. 280). | 3 out 4 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Schubert & Lionberger 1995 | “Mutual connectedness is the joining of the nurse and client in a relationship committed to the health and healing of the client. The nurse remains constant in caring, listening to, and focusing on the client. Client’s trust may fluctuate until a feeling joining or bonding occurs in the relationship” (p. 109). | 2 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Townsend & McWhirter 2005 | Borrowed – Connectedness occurs “when a person is actively involved with another person, object, group, or environment, and that involvement promotes a sense of comfort, well-being, and anxiety-reduction” (Borrowed from Hagerty, Lynch-Sauer, Patusky, and Bouwsema, 1993, p. 293 as cited by Townsend & McWhirter 2005, p. 193). | 3 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Culturally Influenced Conception of Self | |||||||

| Beyers et al. 2003 | Borrowed – Connectedness “refers to high levels of concern about parents’ well-being, high levels of empathy, strong and pervasive emotional ties with parents, openness and reciprocity in the communication with parents, and low levels of separateness from parents” (Borrowed from Frank et al. 1988, as cited by Beyer et al. 2003, p. 352). | 4 out 7 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Huiberts et al. 2006 | Provides a positive and negative definition. “In a positive way, connectedness is defined as emotional closeness: the presence of positive affection and confidence in the availability of parents as a source of help. In a negative way, connectedness is defined as the absence of emotional distance and conflicts” (p. 316). | 3 out 7 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Liu et al. 2005 | “Connectedness was defined as child’s effort to affiliate/connect with his/her mother. Mother encouragement of connectedness included maternal behaviors that promoted the child’s connectedness and affiliation” (p. 491). | 1 out 7 | − | + | + | − | + |

| Personality Trait | |||||||

| Lee & Robbins 1998 (Lee et al. 2001 | “Social connectedness is defined as the subjective awareness of being in close relationship with the social world. The experience of interpersonal closeness in the social world includes proximal & distal relationships with family, peers, acquaintances, strangers, community, and society. It is the aggregate of all these social experiences that is gradually internalized by the individual & serves as a foundation for a sense of connectedness” (Lee & Robbins 1998, p. 338). | 2 out 7 | + | + | − | − | + |

| Rush & Burnham, 1995 | “Connectedness is a personality characteristic that is a relatively more adaptive form of dependency and represents a valuing of relationships and sensitivity to the effects of one’s actions on others” (p. 337). | 2 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Affective Qualities of Positive Social Interactions with Significant Others | |||||||

| Edwards et al. 2006 | “A sense of connectedness with one’s teammates is a common consequence of the shared experiences of the team membership” (p. 136). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Grossman & Bulle 2006 | Adolescent–non-parental adult connectedness is defined as “the degree to which youth feel they have a caring and supportive relationship with a non-parental adult” (p. 788). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Leidy & Haase 1999 | Borrowed - “Connectedness is a sense of a significant, shared, and meaningful relationship with other people, a spiritual being, nature, or aspects of one’s inner self” (Haase et al. 1992 as cited by Leidy & Haase 1999, p. 72). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Resnick et al. 1993 (Resnick et al. 1997) | Family connectedness referred to as “adolescents who indicated that they enjoyed, felt close to and cared for by family members” (Resnick et al. 1993, p. S5). Also “referred to a sense of belonging and closeness to family, in whatever way family was comprised or defined by the adolescents” (Resnick et al. 1993, p. S6). | 3 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| School connectedness referred to as “students who enjoyed school, experiencing a sense of belonging and connectedness to it” (Resnick et al. 1993, p. S5). | 1 out 7 | − | + | + | − | + | |

| Rew 2002 | Borrowed - “Connectedness refers to the individual’s perception that important others such as parents, teachers, church leaders, and peers care about the individual” (Blum et al. 1989 as cited by Rew 2002, p. 55). | 1 out 7 | + | + | + | − | − |

| Shochet et al. 2006 | Borrowed - “School connectedness is defined as “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment” (Goodenow 1993 as cited by Shochet et al. 2006, p. 170). | 3 out 7 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Waters et al 2009 | Borrowed - School connectedness is “the belief by students that adults in that school care about their learning as well as about them as individuals” (Wingspread Conference, 2004 ¶ 1 as cited by Waters et al 2009, p. 517). | 2 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

| Whitlock 2006 | School connectedness was defined as “a psychological state of belonging in which individual youth perceive that they and other youth are cared for, trusted, and respected by collections of adults that they believe hold the power to make institutional and policy decisions” (p. 15). | 4 out 7 | + | + | + | − | + |

None of the reviewed definitions met all criteria for adequacy. The most commonly missed criterion was providing the essential attributes of connectedness. The greatest number of attributes identified in the definitions was four and only four (out of 27) definitions included this many attributes (Beyers et al. 2003, Grossman & Bulle 2006, Whitlock 2006, Barber & Schluterman 2008) — indicating that the majority of the definitions failed to describe the essence of connectedness.

Two definitions directly used the term “connectedness” (Resnick et al. 1997, Liu et al. 2005). All definitions were stated in positive terms. Although the majority of definitions used clear language, three used obscure or figurative language that made the definition difficult to understand. For example, Clark and Ladd’s (2000) definition included the phrase “dyadic property”. Similarly, other authors used vague phrases such as “quality ties” (Ong & Allaire 2005) or “social world” (Lee & Robbins 1998).

Only five of the 27 definitions reflected that connectedness may be measured on a continuum. All but six definitions indicated the context in which connectedness occurred. The most common context in which connectedness was examined in the literature set was among children/adolescents and their parents. Other contexts were at school (between adolescents and their teachers and peers), within healthcare settings (between nurses and their patients), and in other natural groups (between adults and their friends, family members, romantic partners, teammates, or colleagues).

An adequate definition of connectedness

Based on the identified attributes of connectedness and the evaluation of definitions, a broad definition of connectedness was derived that meets the criteria for definitions outlined above: “In social relationships, connectedness is the degree to which a person perceives that he/she has a close, intimate, meaningful, and significant relationship with another person or group of people. This perception is characterized by positive expressions (i.e., empathy, belonging, caring, respect, and trust) that are both received and reciprocated, either by the person or between people, through affective and consistent social interactions”.

Boundaries

Boundaries of connectedness were determined by asking questions similar to those Haase et al. (2009) used to determine the boundaries of resilience. Questions were related to contextual influences (What are the conditions under which connectedness occurs, varies, or disappears?), dimensions (Does connectedness have subjective and/or objective dimensions? Does it have psychological and/or physiological dimensions?), and underlying assumptions (Does connectedness exhibit growth or stability and is it considered a state or trait?).

Contextual influences

Based on the articles reviewed, connectedness most commonly occurs in the context of social relationships. Connectedness does not occur when a person feels uncomfortable. For example, Leidy and Haase (1999) reported that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease felt uncomfortable or embarrassed in public places because of their treatments and symptoms. These feelings led to an increased sense of social disconnectedness because of their reluctance to venture out. Connectedness also was absent when persons experienced mistrust (Lee & Robbins 1998) or were violated by others (Rew 2002). When Rew compared her findings to other studies in the literature, she concluded that homeless youths with histories of sexual abuse perceived themselves to be less socially connected, lonelier, and less healthy than the non-homeless youths described in other studies. Decisions about how connectedness, once established, may disappear could not be made because the literature set did not address such conditions.

Subjective/objective dimensions

There appear to be both subjective and objective dimensions of connectedness. Over two thirds of the articles examined connectedness through self-reported measures asking people about their relationship with family members, peers, or members within a community. Most of these instruments contained questions about feeling cared for, valued, respected, and understood by others (e.g., Resnick et al. 1993) or about the ability to establish and maintain close relationships with others (e.g., Lee & Robbins 1998). Other studies also included questions about particular activities with others rather than only focusing on the affective response of feeling connected (Karcher & Lee 2002, Rew 2002). For example, Karcher and Lee developed an instrument that assesses both the degree of involvement and affection experienced in close relationships.

A few studies examined objective dimensions of connectedness. For example, Clark and Ladd (2000) proposed that connectedness in young children is manifested directly in the personal narrative conversations they have with their mother. In this investigation, connectedness between mothers and their five-year-old child was assessed by having observers view each narrative conversation and rate the dyad on six constructs of mutual: positive engagement; warmth; reciprocity; happy tone; intimacy; and intensity. Similarly, Grotevant and Cooper (1998) developed a Q-sort that was used by observers to assess individuality and connectedness qualities in dyadic relationships. Thus, connectedness appears to have attributes that can be objectively observed.

Psychological/physiological dimensions

Psychological concepts that have been associated with connectedness include self-esteem, anxiety, depression, coping, and well-being (e.g., Lee & Robbins 1998, Shochet et al. 2006; Person et al. 2007). These psychological concepts were most often described as consequences of connectedness.

Two studies examined physiological dimensions of connectedness. Ong and Allaire (2005) found that people who were perceived to be more socially connected had diminished diastolic and systolic blood pressure reactivity when encountering daily negative emotional states. Edwards et al. (2006) found a positive association between salivary testosterone levels and connectedness among male and female college soccer players. What is unclear is the causal relationship between these variables. Further work is needed to replicate these findings and to determine how the variables are associated.

Growth vs. stability assumptions

Based on the reviewed literature, it is unclear if connectedness is a phenomenon that exhibits growth (change) or stability. Though some investigators defined and/or measured connectedness on a continuum (e.g., Shochet et al. 2006), other researchers implied that connectedness was a constant and stable characteristic (e.g., Lee & Robbins 1998, Lee et al. 2001, Rude & Burnham 1995). Many other investigators failed to indicate either assumption. One might think that connectedness could change over time; however, this assumption was not studied in the selected literature set. Understanding how connectedness either changes or remains stable over time is important to measurement; the stability or tendency to change over time has implications for how and when a concept should be measured or whether or not interventions can influence connectedness.

State vs. trait assumptions

There seemed to be conflicting assumptions regarding whether or not connectedness was state-like or trait-like. The majority of the investigators implied that connectedness was situational or state-like. For example, connectedness was commonly described as occurring in social relationships, especially when a person felt cared for, respected, and understood by other people in the relationship. In contrast, other investigators referred to connectedness as a stable personality characteristic, which indicates that connectedness is trait-like. These two conflicting assumptions require further investigation.

Antecedents

The antecedents of connectedness were rarely described and difficult to clearly identify; however, at least three antecedents were implied in the literature (see Table 3). The first and most commonly implied antecedent that fostered connectedness was having consistent interactions with people who exhibited behaviors that were supportive and affectionate. For example, a person connects with another person when he/she experiences repetitive interactions that involve nurturing and caring behaviors.

Table 3.

Antecedents of Connectedness

| Antecedents | Sources |

|---|---|

| Consistent interactions with people who exhibit behaviors that are supportive and affectionate |

Barber & Schulterman (2008) Grossman & Bulle (2006) Heifner (1993) Huiberts et al. (2006) Karcher (2005) Karcher & Lee (2002) Lee & Robbins (1998) Lee et al. (2001) Liu et al. (2005) Miner-Williams (2007) Resnick et al. (1993) Resnick et al. (1997) Rew (2002) Schubert & Lionberger (1995) Shochet et al. (2006) Waters (2009) |

| Desire or need to connect |

Heifner (1993) Karcher (2005) Karcher & Lee (2002) Lee & Robbins (1998) Lee et al. (2001) Miner-Williams (2007) Resnick et al. (1993) Resnick et al. (1997) Schubert & Lionberger (1995) Townsend & McWhirter (2005) |

| Recognition of sharing similar experiences, characteristics, interests, or beliefs |

Edwards et al. (2006) Grossman & Bulle (2006) Huiberts et al. (2006) Leidy & Haase (1999) Liu et al. (2005) |

The second antecedent implied in the literature was a person’s need or desire to connect. Some authors described the need or desire to connect as an innate human characteristic that is fulfilled when people experience consistent interactions that are nurturing and supportive (Lee & Robbins 1998, Karcher 2005, Townsend & McWhirter 2005). Other authors described the need or desire to connect as a person’s response to another person who needs help such as a nurse’s response to help a patient with a health problem (Heifner 1993, Schubert & Lionberger 1995, Miner-Williams 2007).

The third probable antecedent identified was sharing similar experiences, characteristics, interests, or beliefs with other people. For example, Edwards et al. (2006) believed that a person’s sense of connectedness to their teammates was the result of the shared experiences of team membership. Similarly, Grossman and Bulle (2006) reviewed adult–youth programs and reported that the most common determinant for an adolescent feeling connected to non-parental adults was shared interests or personality characteristics. The notion of shared experiences, characteristics, interests, or beliefs with others was also implied as an antecedent in the context of parent–child relationships (Liu et al. 2005, Huiberts et al. 2006) and nurse–patient relationships (Heifner 1993).

Consequences

Researchers have reported that connectedness is associated with a variety of positive psychosocial outcomes (see Table 4) such as higher self-esteem, enhanced psychosocial/emotional adjustment (e.g., less anxiety, stress, and depression), adaptive interpersonal skills, and improved health status and well-being. Other consequences noted, particularly for adolescents, were higher academic achievement and diminished risk-taking behaviors. Although several researchers proposed that connectedness may be predictive of these positive outcomes, most of the evidence was based on correlations. Thus, further empirical work is needed to determine how or if connectedness influences the reported outcomes.

Table 4.

Consequences of Connectedness

| Consequences | Sources |

|---|---|

| Higher self-esteem |

Grotevant & Copper (1986) Grotevant & Copper (1998) Karcher (2005) Lee & Robbins (1998) Lee et al. (2001) Waters (2009) |

| Enhanced psychosocial/emotional adjustment |

Gavazzi & Sabatelli (1990) Lee & Robbins (1998) Lee et al. (2001) Miner-Williams (2007) Ong & Allaire (2005) Person et al. (2007) Resnick et al. (1993) Resnick et al. (1997) Rew (2002) Shochet et al. (2006) Waters (2009) |

| Adaptive interpersonal skills |

Clark & Ladd (2000) Grotevant & Copper (1986) Grotevant & Copper (1998) Gavazzi & Sabatelli (1990) Grossman & Bulle (2006) Lee & Robbins (1998) Lee et al. (2001) |

| Improved health status and well-being |

Leidy & Haase (1999) Ong & Allaire (2005) Rew (2002) Waters (2009) |

| Higher academic achievement and/or engagement |

Grossman & Bulle (2006) Karcher (2005) Waters (2009) |

| Diminished risk-taking behaviors |

Barber & Schluterman (2008) Grossman & Bulle (2006) Resnick et al. (1993) Resnick et al. (1997) Waters (2009) |

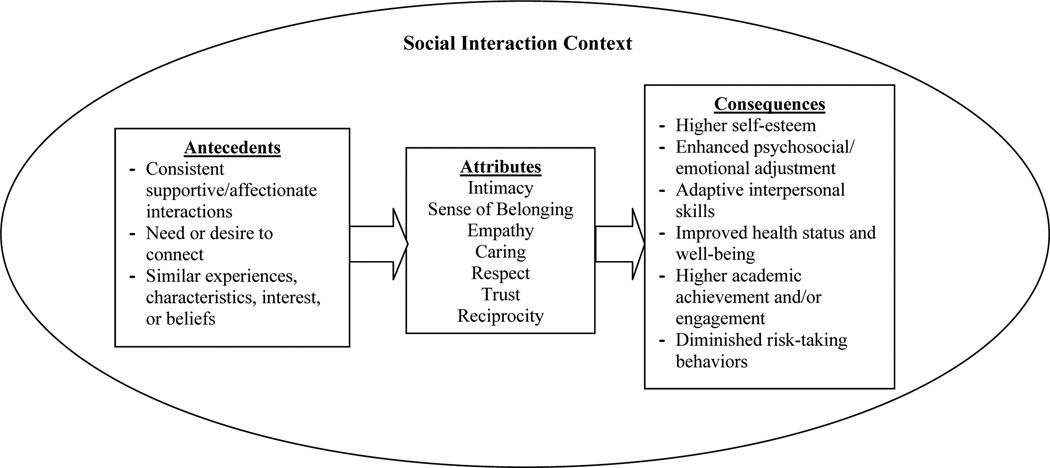

Preliminary theoretical framework

Based on the results of this analysis, a preliminary theoretical framework of connectedness was developed. Figure 1 identifies antecedents, attributes, and consequences of connectedness in the framework.

Figure 1.

Preliminary Theoretical Framework of Connectedness

DISCUSSION

Study limitations

For this analysis, literature sources were limited to studies that examined connectedness within social relationships and may not be generalizable to other contexts (e.g., spiritual connectedness or connectedness to nature). Since the literature search was limited to articles using the word “connectedness” in the title, a number of relevant sources may have been excluded. A strategy used to mitigate this limitation included reviewing the reference lists of the selected literature for other relevant sources. Because the analysis involved an inductive approach, using only literature sources, there was a potential for bias. Strategies taken to minimize bias included using an audit trial when appropriate (see Tables) and validating interpretations of findings with co-authors.

Theoretical implications

Although the importance of patient–provider relationships/connectedness has been long recognized and explored by nursing theorists (Peplau 1952, Travelbee 1971, King 1981, Watson, 1988), few theories explain how this phenomenon is fostered and the mechanisms through which connectedness contributes to positive patient health outcomes. Likewise, theoretical frameworks of health-related quality of life (e.g., Ferrell et al. 2003, Ferrans et al. 2005) suggest that social relationships (i.e., relationships with family, friends, and healthcare providers) lead to positive health outcomes; however, these frameworks provide little insight into how such relationships enhance a person’s quality of life. One explanatory theoretical framework that may help guide future research on connectedness is the Resilience in Illness Model (RIM), previously referred to as the Adolescent Resilience Model (Haase 2004). The RIM specifies the protective and risk factors that either enhance or hinder resilience in chronically ill people. One of the key protective factors – Social Integration – reflects the hypothesis that people’s perceptions of their relationships with healthcare providers influence their resilience and quality of life by influencing the degree to which they use positive coping strategies and hope-derived meaning. Although the RIM suggests that patient–provider relationships are important, little is known about how people become connected to their healthcare providers. Therefore, once the antecedents and critical attributes of patient–provider connectedness outlined in the preliminary theoretical framework have been validated, the RIM may be a useful framework to evaluate the hypothesized relationships between patient–provider connectedness and the proximal and distal outcomes of resilience and quality of life.

CONCLUSION

In health care, connectedness is inadequately defined and has not been adequately examined. Specific reasons that the applicability of connectedness in health care is in its infancy include a limited understanding of the (1) attributes/characteristics that define patient–provider connectedness; (2) antecedents or conditions that encourage the development of patient–provider connectedness; and (3) how this phenomenon influences patient health outcomes. Other reasons relate to the major conceptual issues identified in this analysis. First, the diverse and segregated historical perspectives in which connectedness has been conceptualized or defined have hampered efforts to build upon previous research. Second, the definitions of connectedness are inadequate because little consideration has been devoted to examining the essential attributes of connectedness. Although seven attributes were identified in this analysis, further research is needed to determine if these attributes can be validated. Third, the boundaries of connectedness seemed to be blurred by the various conceptualizations and need further exploration — specifically, contextual influences, dimensions, and assumptions need to be closely examined. Fourth, there has been a lack of research on identifying the antecedents of connectedness. The antecedents extracted through this analysis provide direction for future research. Lastly, although connectedness has been associated with a variety of positive psychosocial outcomes, further work is needed to determine the strength and direction of these hypothesized relationships.

Three research recommendations are offered for refining connectedness in patient–provider relationships. These recommendations are based on Haase et al. (1999) decision-making process for theory and instrument development. First, additional research is needed to examine connectedness from the perspectives of patients and healthcare providers in order provide a clearer description of the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of connectedness, as well as the conditions under which patient-provider connectedness is manifested. Qualitative methods are believed to be well suited for further clarification of unclear concepts (Morse et al. 1996). Second, the preliminary theoretical framework derived from this analysis requires further examination and refinement using quantitative techniques. Third, psychometrically sound instruments that measure the attributes of patient–provider connectedness and help examine the relationships among connectedness, its antecedents, and its consequences need to be identified or developed. The development of such instruments will help answer questions about the preliminary theoretical framework and allow refinements to the framework based on statistical analyses such as factor analysis. Factor analysis will help provide valuable information regarding the dimensionality and structure of connectedness in relation to instrumentation. Clarifying connectedness will provide a better understanding of how this concept can be applied in healthcare settings, guide the development of interventions to promote patient-provider connectedness, and identify the extent to which it influences patient health outcomes. Practice implications include (1) raising an awareness of the importance of patient-provider connectedness and its relationship to positive patient outcomes; and (2) developing staff education programs to help healthcare providers understand the behaviors and attitudes that foster connectedness.

Summary Statements.

What is already known about this topic

Patient–provider connectedness is believed to have a positive influence on patient health outcomes.

Research to demonstrate the significance of patient–provider connectedness is lacking due to a limited understanding of its defining characteristics and mechanisms that foster and/or maintain the connection.

Although connectedness is a commonly used term to define meaningful social relationships, there is a great deal of inconsistency in how this concept is conceptualized and measured.

What this paper adds

Identification of attributes of connectedness: intimacy, sense of belonging, caring, empathy, respect, trust, and reciprocity.

Development of an adequate, broad definition of connectedness that can be validated through future research.

A preliminary theoretical framework of connectedness that, with further research, may be used to conceptually refine patient–provider connectedness and lead to the development of a explanatory theoretical framework.

Implications for practice and/or policy

Healthcare providers’ knowledge of the antecedents of connectedness (i.e., consistent supportive/affective interactions, desire to connect, shared experiences) may contribute to their behaviors/attitudes that foster connectedness with patients.

To foster awareness of the potential benefit of connectedness for patient health outcomes, staff education programs may include content on factors influencing patient–provider connectedness.

After the preliminary theoretical framework is validated from patients’ and providers’ experiences and refined through quantitative techniques, it can be used to predict patient health outcomes and guide interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the first author’s doctoral scholarships and training fellowships: American Cancer Society Doctoral Scholarship in Cancer Nursing (DSCN-05-181-01); F31 Individual National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (F31 NR009733-01A1); T32 Institutional National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (NR009733-01A, PI: Austin); Walther Cancer Institute Pre-doctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest have been declared by the authors.

Author Contributions:

CRP & JEH were responsible for the study conception and design

CRP & JEH performed the data collection

CRP performed the data analysis.

CRP was responsible for the drafting of the manuscript.

CRP, JEH & WCK made critical revisions to the paper for important intellectual content.

CRP, JEH & WCK provided statistical expertise.

CRP & JEH obtained funding

CRP & JEH provided administrative, technical or material support.

JEH supervised the study

Contributor Information

Celeste R. Phillips-Salimi, Assistant Professor, University of Kentucky College of Nursing, Lexington, KY.

Joan E. Haase, Holmquist Professor of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, Indiana University School of Nursing, Indianapolis, IN.

Wendy Carter Kooken, Postdoctoral Fellow, Indiana University School of Nursing, Indianapolis, IN.

References

- Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R, Hawkins RP. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):474–486. doi: 10.1002/pon.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas SJ, Grant RW, Ferris TG, Chang Y, Barry MJ. Patient-physician connectedness and quality of primary care. Annuals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150(5):325–335. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-5-200903030-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Schluterman JM. Connectedness in the lives of children and adolescents: a call for greater conceptual clarity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(3):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Inui T, the Relationship-Centered Care Research Network Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006a;21(Suppl. 1):S3–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006b;21(6):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers W, Goossens L, Vansant I, Moors E. A structural model of autonomy in middle and late adolescence: connectedness, separation, detachment, and agency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;32(5):351–365. [Google Scholar]

- Brucker PS, McKenry PC. Support from health care providers and the psychological adjustment of individuals experiencing infertility. Jounral of Obstetric Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2004;33(5):597–603. doi: 10.1177/0884217504268943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KE, Ladd GW. Connectedness and autonomy support in parent-child relationships: links to children's socioemotional orientation and peer relationships. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(4):485–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Nagel E. An Introduction to Logic and Scientific Method. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and Company; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DA, Wetzel K, Wyner DR. Intercollegiate soccer: saliva cortisol and testosterone are elevated during competition, and testosterone is related to status and social connectedness with teammates. Physiology and Behavior. 2006;87(1):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, Duberstein PR. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61(7):1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL. The relationship between continuity of care and the health behaviors of patients: Does having a usual physician make a difference? Medical Care. 1999;37(6):547–555. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005;37(4):336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Smith SL, Cullinane CA, Melancon C. Psychological well being and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Cancer. 2003;98(5):1061–1071. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavazzi SM, Sabatelli RM. Family system dynamics, the individuation process, and psychosocial development. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1990;5(4):500–519. [Google Scholar]

- Gavazzi SM, Sabatelli RM, Reese-Weber M. Measurement of financial, functional, and psychological connections in families: conceptual development and empirical use of the multigenerational interconnectedness scale. Psychological Reports. 1999;84:1361–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JB, Bulle MJ. Review of what youth programs do to increase the connectedness of youth with adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(6):788–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Individuation in family relationships: a perspective on individual differences in the development of identity and role-taking skills in adolescence. Human Development. 1986;29:82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Individuality and connectedness in adolescent development: review and prospects for research on identity, relationships, and context. In: E Skoe E, von der Lippe A, editors. Personality Development in Adolescence: A Cross National and Lifespan Perspective. London: Routledge; 1998. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE. The adolescent resilience model as a guide to interventions. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004;21(5):289–299. doi: 10.1177/1043454204267922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE, Britt T, Coward DD, Leidy NK, Penn PE. Simultaneous concept analysis of spiritual perspective, hope, acceptance and self-transcendence. Imag – Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1992;24(2):141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1992.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE, Chen C, Phillips-Salimi C, Bell C. Resilience. In: Peterson S, Bredow T, editors. Middle-Range Theories: Application to Nursing Research. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009. pp. 326–358. [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE, Heiney SP, Ruccione KS, Stutzer C. Research triangulation to derive meaning-based quality-of-life theory: adolescent resilience model and instrument development. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;83(Suppl 12):125–131. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<125::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin RL. On Definitions as Guides to Measurement. St. Louis, MO: Small Groups Research Center, Social Science Institute; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Heifner C. Positive connectedness in the psychiatric nurse-patient relationship. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1993;7(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(93)90017-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsenroth MJ, Peters EJ, Ackerman SJ. The development of therapeutic alliance during psychological assessment: patient and therapist perspectives across treatment. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2004;83(3):332–344. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8303_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS. Inducing a definition of 'hope' through the use of grounded theory methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1984;9(4):357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1984.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huiberts A, Oosterwegel A, VanderValk I, Vollebergh W, Meeus W. Connectedness with parents and behavioural autonomy among Dutch and Moroccan adolescents. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2006;29(2):315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ. The effects of developmental mentoring and high school mentors' attendance on their younger mentees' self-esteem, social skills, and connectedness. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42(1):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ, Lee Y. Connectedness among Taiwanese middle school students: a validation study of the hemingway measure of adolescent connectedness. Asia Pacific Education Review. 2002;3(1):92–114. [Google Scholar]

- King IM. A Theory for Nursing: Systems, Concepts, Process. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Draper M, Lee S. Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48(3):310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Robbins SB. The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45(3):338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy NK, Haase JE. Functional status from the patient's perspective: the challenge of preserving personal integrity. Research in Nursing and Health. 1999;22(1):67–77. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<67::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Chen X, Rubin KH, Zheng S, Cui L, Li D, Chen H, Wang L. Autonomy- vs. connectedness-oriented parenting behaviours in Chinese and Canadian mothers. International Jounral of Behavioral Development. 2005;59(6):489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors' satisfaction with information. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;57(3):342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelich WD, Murphy DA. Effects of empowerment among HIV-positive women on the patient-provider relationship. AIDS Care. 2003;15(4):475–481. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000134719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus RP., Jr Adolescent care: reducing risk and promoting resilience. Primary Care. 2002;29(3):557–569. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(02)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51(7):1087–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner-Williams D. Connectedness in the nurse-patient relationship: a grounded theory study. Issues Ment Health Nursing. 2007;28(11):1215–1234. doi: 10.1080/01612840701651462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Hupcey JE, Mitcham C, Lenz ER. Concept analysis in nursing research: a critical appraisal. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice. 1996;10(3):253–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Allaire JC. Cardiovascular intraindividual variability in later life: The influence of social connectedness and positive emotions. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20(3):476–485. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau HE. Interpersonal Relations in Nursing. New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Person B, Bartholomew LK, Addiss D, van den Borne B. Disrupted social connectedness among Dominican women with chronic filarial lymphedema. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;68(3):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger LH, Udry JR. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA – The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Harris LJ, Blum RW. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Paediatric Child Health. 1993;29(Suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L. Relationships of sexual abuse, connectedness, and loneliness to perceived well-being in homeless youth. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2002;7(2):51–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2002.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers BL. Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In: Rodgers BL, Knafl KA, editors. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations Techniques and Applications. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000. pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rude SS, Burnham BL. Connectedness and neediness: factors of the DEQ and SAS dependency scales. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1995;19:323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert PE, Lionberger HJ. A study of client-nurse interaction using the grounded theory method. Jounral of Holistic Nursing. 1995;13(2):102–116. doi: 10.1177/089801019501300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochet IM, Dadds MR, Ham D, Montague R. School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(2):170–179. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. Complex responsive processes of relating. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S40–S44. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman AL, Matthews DA. What makes the patient-doctor relationship therapeutic? Exploring the connexional dimension of medical care. Annuals of Internal Medicine. 1988;108(1):125–130. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers RF, Barber JP. Therapeutic alliance as a measurable psychotherapy skill. Academic Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):160–165. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.3.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne SE, Kuo M, Armstrong EA, McPherson G, Harris SR, Hislop TG. 'Being known': patients' perspectives of the dynamics of human connection in cancer care. PsychoOncology. 2005;14(10):887–898. doi: 10.1002/pon.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend KC, McWhirter BT. Connectedness: a review of the literature with implications for counseling, assessment, and research. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2005;83:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Travelbee J. Interpersonal Aspects of Nursing. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- van Servellen G, Lombardi E. Supportive relationships and medication adherence in HIV-infected, low-income Latinos. Western Jounral of Nursing Research. 2005;27(8):1023–1039. doi: 10.1177/0193945905279446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 4th edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Waters SK, Cross DS, Runions K. Social and ecological structures supporting adolescent connectedness to school: a theoretical model. Jounral of School Health. 2009;79(11):516–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Nursing: Human Science and Human Care - A Theory of Nursing. National League for Nursing; 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock JL. Youth perceptions of life at school: contextual correlates of school connectedness in adolescence. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;10(1):13–29. [Google Scholar]