Abstract

We report the synthesis, cytotoxicity, and phenotypic analysis of oxazole and thiazole containing fragments. Evaluating the optimal size and heterocycle for growth inhibition and apoptosis showed that activity required at least two thiazoles sequentially connected. This is the first detailed comparison of biological activity between multi-heterocyclic containing fragments.

Introduction

Heterocycles play a key role in medicinal chemistry.1 Oxazole and thiazole derivatives offer diversity when introduced into molecular scaffolds,2 and when incorporated as peptidomimetic features.3 They typically improve the compound’s solubility, while maintaining hydrogen bond acceptors, and increasing the compound’s rigidity.4 Furthermore, heterocycles provide new sites for potential binding interactions through π-stacking with a biological target.5 Studies show that oxazole-based fragments are less flexible than thiazole-based fragments,{Haberhauer, 2008 #1272} but thiazoles hydrogen bond more effectively than oxazoles.{Prince, 2009 #15}{Haberhauer, 2008 #1272}{Prezhdo, 2004 #1313} These physical properties provide the opportunity to tweak the “drug ability” of a compound, selectively incorporating a heterocycle at a desired location to modify the flexibility, π-stacking ability and/or hydrogen bonding capability.

Compounds currently being pursued as natural potent drug candidates incorporate many variants of five-membered rings, including oxazoles and thiazoles. These heterocycles are seen in bioactive classes including anti-cancer7 and anti-HIV agents.8 Azaepothilone B, also known as Ixabepilone when prescribed, is a thiazole-containing molecule that acts by stabilizing microtubules, and inducing apoptosis in cancer cells (Figure 1).7a, 9 Ritonavir is also a thiazole-containing molecule and it is FDA approved to treat HIV infections.7b It is also a protease inhibitor with anti-inflammatory10 and anti-tubercular activity.11 Telomestatin, which is expected to enter phase 1 testing shortly12 is a potent telomerase inhibitor containing linked oxazoles and a thiazoline unit. Telomestatin acts by inhibiting the telomerase activity of cells, and it induces apoptosis once the telomeres are too short to be transcribed.7c Bleomycin, an approved anticancer agent, contains di-thiazoles (Figure 1). 13

Figure 1.

Three approved drugs: Azaepothilone B, Ritonavir and bleomycin) and one expected to enter phase I testing (Telomestatin) that contain oxazoles and thiazoles

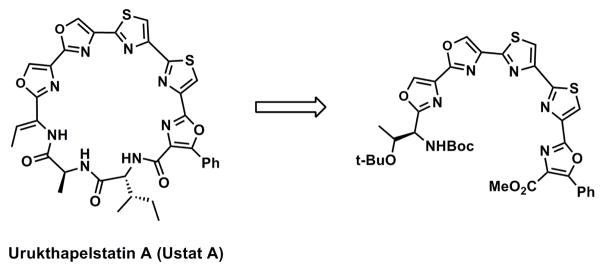

Heterocycles act as conformational constraints, which influences biological activity, particularly in a macrocycle where there are limited conformations already dictated by the ring size. The complexity of natural product-based drugs (e.g. azaepothilone B, telomestatin and bleomycin) make synthesis of these compounds challenging. We were interested in Urukthapelstatin A (Ustat A), a natural product with nanomolar potency against a panel of cell lines (Figure 2).14 Similar in structure to Telomestatin, Ustat A’s potency provides a driving force to investigate its mechanism of action. Containing five heterocycles overall, Ustat A has two oxazoles, two thiazoles, and one phenyl oxazole. However, the synthesis of Ustat A has proven challenging,15 primarily because of the rigidity associated with closing the macrocyclic ring that contains five heterocycles. Exploring the biological activity of a truncated species of Ustat A analogues is logical given the challenges associated with the total synthesis of Ustat A and analogues. Herein we describe the synthesis and biological activity of truncated variants of Ustat A These thiazole and oxazole containing compounds were then tested for the anticancer activity in both cytotoxicity assays and confocal analysis.

Figure 2.

Truncated heterocyclefragment of Ustat A.

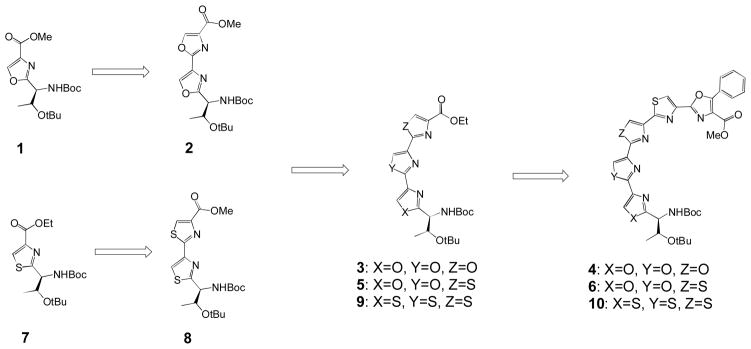

Synthesis of truncated oxazole and thiazole fragments ranging from a single heterocycle to five heterocycles generated ten compounds based on the Ustat A scaffold (Figure 3). Testing these fragments against HCT116 colon cancer cell lines and evaluating their impact on cells using confocal analysis provided evidence of an interesting structure activity relationship. Evaluating the optimal size and heterocycles for cancer cell growth inhibition showed that activity required the presence of at least two thiazoles sequentially connected (6, 8, 9, and 10). Furthermore, we observed that fragments containing five sequential heterocycles, and a minimum of two linked thiazoles (6 and 10), were two fold more cytotoxic than fragments containing fewer heterocycles. Finally we show phenotypic evidence that our compounds induced apoptosis. In summary, this manuscript is the first to discuss a detailed comparison of biological activity between multi-oxazole and thiazole containing fragments, and the first to show that truncating heterocyclic-containing macrocycles maintain activity.

Figure 3.

Evolution of heterocyclic moieties

Results and Discussion

Numerous methods highlight synthetic approaches to the generation of oxazoles and thiazoles.2b, 2c, 16 A widely used method for the synthesis of oxazoles involves cyclization and oxidation of serine (Ser) containing peptides.1f Synthesizing thiazoles is typically reported as the condensation of α-haloketones with thioamide derivatives, which is known as a modified Hantzsch thiazole reaction.17 Preparing sequential oxazole- and thiazole-containing fragments provided the opportunity to compare the heterocycles’ biological activity in cell-based assays. We generated oxazoles via cyclization and oxidation of Ser containing peptides using diethylaminosulfurtrifluoride (DAST) and bromochloroform (BrCCl3). Thiazole fragments were produced using modified Hantzsch thiazole conditions, through condensation of α-haloketones with thioamide analogs.15

The synthetic route is outlined in schemes 1, 2 and 3. The synthesis of the sequential trioxazole-thiazole series (compounds 1, 2, 3 and 4) were prepared by the route described in Scheme 1. The oxazole precursor dipeptide was generated by coupling free acid Boc-Thr(OtBu)-OH and free amine H2N-Ser(Bn)-OMe using 2-(1H-Benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronoium hexafluorphosphate (TBTU) and diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA). Removal of the benzyl protecting group occurred using hydrogenand Pd/C (10%). Obtaining the oxazole involved a two step procedure with the first step utilizing an intramolecular cyclization via a fluorinating agent DAST and then addition of K2CO3 yielded an intermediate oxazoline. Oxidation using BrCCl3 and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) generated 1 in excellent yield (85% for 3 steps).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of trioxazole-thiazole fragment (4)

Conditions:

a) TMSCH2N2, Benzene/MeOH (3:1), 98%; b) Ser(Bzl)-OMe, TBTU, iPr2NEt, CH2Cl2, 2 steps yield: 90% for 1, 95% for 2, and 92% for 3; c) H2, Pd/C, EtOH; d) DAST, CH2Cl2 / K2CO3; e) DBU, BrCCl3, CH2Cl2, 3 steps yield: 85% for 1 and 2, 70% for 3; f) LiOH, MeOH; g) NH4OH, MeOH, ultrasound; h) Lawesson’s reagent, DME, 55%, 2 steps; i) Bromoketo Phenyloxazole, KHCO3, DME; j) TFAA, pyridine, DME, 72%, 2 steps

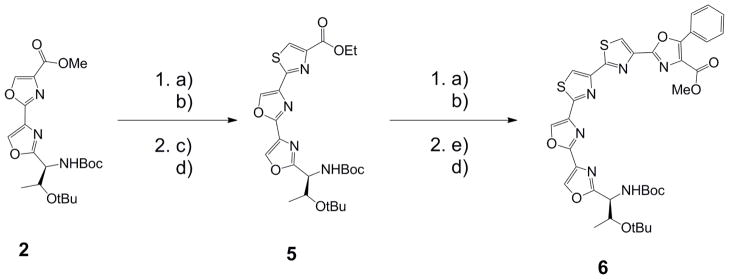

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dioxazole-dithiazole fragment (6)

Conditions:

a) NH4OH, MeOH, ultrasound; b) Lawesson’s reagent, DME, 2 steps yield: 77% for 5, 70% for 6; c) BrCH2COCO2Et, KHCO3, DME; d) TFAA, pyridine, DME, 2 steps yield: 77% for 5, 69% for 6; e) Bromoketo Phenyloxazole, KHCO3, DME

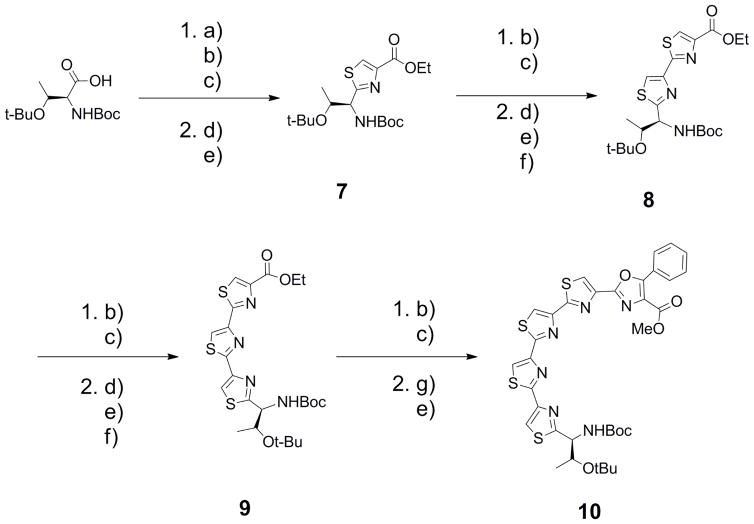

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of tetrathiazole fragment (10)

Conditions:

a) TMSCH2N2l Benzene/MeOH (3:1); b) NH4OH, MeOH, ultrasound; c) Lawesson’s reagent, DME, 2 steps yield: 60% for 7, 53% for 8, 73% for 9 and 73% for 10; d) BrCH2COCO2Et, KHCO3, DME; e) TFAA, pyridine, DME, 2 steps yield: 78% for 7, 88% for 10; f) NaOEt, EtOH, 3 steps yield: 97% for 8, 87% for 9; g) Bromoketo Phenyloxazole, KHCO3, DME

Acid deprotection of 1 using LiOH, subsequent coupling to serine, deprotection of the alcohol, and formation of the oxazole resulted in 2 (85% for 3 steps). Hydrolysis of the ester on 2, coupling of serine, deprotection, and formation of the oxazole generated 3 (70% for 3 steps). Finally, hydrolysis of the ester, conversion to the amide, and subsequently the thio amide prepared the compound for thiazole formation. Performing the two steps via a modified Hantzsch thiazole reaction18 with the bromoketo-phenyl oxazole fragment15 generated 4 (72% for 2 steps).

The synthesis of the sequential dioxazole-dithaizole fragment 6 was prepared by the route described in Scheme 2. Synthesis of 5 started from the dioxazole 2, whereupon deprotection of the acid using LiOH, conversion into the amide, and subsequently the thioamide prepared the molecule for a Hantzsch thiazole reaction. Reaction with ethylbromopyruvate and KHCO3 yielded the intermediate thiazoline, whereupon subsequent dehydration generated the thiazole (5, 77% for 2 steps). Utilizing a similar procedure to that described for generating 5, we synthesized the heterocyclic fragment 6 (69% for 2 steps).

Construction of 10 is summarized in Scheme 3. Starting with free acid Boc-Thr(OtBu)-OH, acid protection using TMSCH2N2, and subsequent conversion of the ester to the thioamide occurs via reaction with ammonium hydroxide and then Lawesson’s reagent. Using the two step Hantzsch thiazole reaction with the thioamide and ethylbromopyruvate and then elimination of the thiazoline, yielded 7 (78% for 2 steps). Repeating this method on 7 gave 8 (97% for 3 steps). Generation of 9 (87% for 3 steps) followed the same synthetic steps as those described for synthesizing the thiazole for 7 and 8. Finally a Hantzsch thiazole reaction was performed using bromoketo phenyl oxazole instead of ethylbromopyruvate, which yielded 10 (88% for 2 steps).

Structure-activity relationships

The compounds were tested for at 40 μM for their cytotoxicity in the colon cancer cell line HCT-116. Utilizing a CCK8 assay, (Figure 3),19 we observed greater than 50% growth inhibition when cells were treated with compounds containing two linked thiazoles (6, 8, 9 and 10). Although compounds 4 and 5 contain a single thiazole, significant cytotoxicity requires two connected thiazoles within the compound structure (compare the activity of 7 to that of 8). This interesting phenomenon supports the hypothesis that sequential thiazole moieties are required to provide a semi-flexible structure, and that a single thiazole may not be sufficient. Further, these data suggest that hydrogen bonding between the compound and biological target are critical for biological activity.

IC50 values of compound 6 (two thiazoles) and 10 (four thiazoles) were compared to non-toxic compound 2 (two oxazoles). Compound 2 was tested up to 100uM (the highest concentration possible under our assay conditions) and it had growth inhibition of <50%. Comparing the IC50 values of compounds 6 and 10 to the growth inhibition of 2 showed that both compounds 6 and 10 were statistically more cytotoxic than compound 2 (P value < 0.0011 for 6 and the P value = 0.0006 for 10 when compared to 2 as per the Student’s t test).

Evaluating the IC50 values of the potent compounds (Table 1, compounds 6, 8, 9 and 10) suggested that not only are linked thiazoles important for activity, but five sequential heterocycles (6 and 10) are the ideal size for maximum growth inhibition. These data support the premise that the number of heterocycles linked together plays a role in the biological activity of heterocycle-based compounds.

Table 1.

IC50* values of potent analogs (μM)

| Fragments | 2 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | > 100§ | 18.2±4.7 | 19.4±3.1 | 26.5±4.7 | 18.7±3.4 |

IC50 values of 6, 8, 9 and 10 with their standard deviations against colon cancer cell line HCT-116 using CCK8 assay. Data represents results from a concentration curve taken from seven concentrations, where each concentration data point is from 3 separate experiments performed in quadruplicate Concentration curves are available in supplementary material.

100uM is the highest concentration tested

Phenotype Analysis

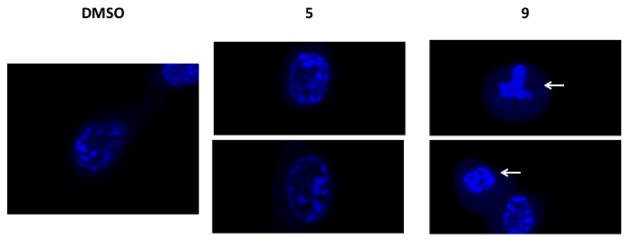

Examining the morphological changes in HCT116 cells treated with Ustat A fragments involved treatment of cells with either non-toxic compound 5 or cytotoxic compound 9 for 24 hours. Cell shrinkage and nuclear condensation (pyknosis) was observed in 30% of 9-treated cells, but was not seen in DMSO-treated samples (Figure 5). Although 12% of 5-treated cells also displayed some nuclear condensation, the chromatin of cells treated with 5 was less condensed than the chromatin of 9-treated cells. Pyknosis is seen in cells undergoing early stages of apoptosis or necrosis (oncosis).20 The controlled process of apoptotic cell death usually affects individual cells or cell clusters within a field.21 Necrosis is uncontrolled and induces morphological changes across wide fields of cells. The plasma membranes of 9- and 5-treated cells were intact, and plasma budding or blistering was not observed at this time point. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of necrotic cell death, the pattern of cell shrinkage and peripheral nuclear condensation in 9-treated cells is suggestive of apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Visualization of HCT-116 cells treated with DMSO (24 hr; 1%), 5 (24 hr; 10 μM) or 9 (24 hr; 10 μM). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst 33342 dye and visualized with a 100X objective. White arrows indicate chromosome condensation (pyknosis).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have evaluated structure-activity relationships of trunctated Ustat A oxazole- and thiazole-containing analogs in cytotoxicity assays and via confocal analysis. Our SAR studies showed that not only are sequential thiazole fragments critical for biological activity, but longer sequences of heterocycles (five) are more cytotoxic than small sequences (one or two). We have shown that the IC50 values match the phenotypic analysis whereby cytotoxic compound 9, induces cell shrinkage and nuclear condensation. By comparison, non-toxic compound 5 does not induce significant changes in cell morphology. These phenotypic observations suggest that 9 may induce apoptosis. Given the importance of these heterocycles in prescribed drugs and drug candidates, understanding the role that oxazoles and thiazoles play within a given structure is the key to successfully designing new drugs. Further studies on heterocyclic fragments are on-going and will be published in due course.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Growth inhibition of compounds at 40 μM. Percentage growth inhibition of treated HCT-116 cells was measured using a CCK8 assay. Data represents results for compounds 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 each at 40uM concentration. Data is from 3 separate experiments performed in quadruplicate and the error bars are the standard errors of the mean (SEM).

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of New South Wales for a scholarship to S.J.K, a tuition fee waiver to D.P.R., and support of D.M.R. We thank NIH 1R01CA137873 for support of C.C.L. and C.M.P.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

References

- 1.a) Baumann M, Bazendale IR, Ley SV, Nikbin N. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2011;7:422–495. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boger DL. Patent application: PCT/US2007/019471/ US2010/0075931 A1. 2012;12:310, 474.; c) Dang Q, Yan L, Cashion DK, Kasibhatla SR, Jiang T, Taplin F, Jacintho JD, Li H, Sun Z, Fan Y, DaRe J, Tian F, Li W, Gibson T, Lemus R, van Poelje PD, Potter SC, Erion MD. J Med Chem. 2011;54:153–165. doi: 10.1021/jm101035x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dosa PI, Ruble JC, Fu GC. J Org Chem. 1997;62:444–445. doi: 10.1021/jo962156g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Duchler M. J Drug Target. 2012;20:389–400. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2012.669384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Hughes RA, Moody CJ. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2007;46:7930–7954. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Wagner B, Schumann D, Linne U, Koert U, Marahiel MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10513–10520. doi: 10.1021/ja062906w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Sivonen K, Leikoski N, Fewer DP, Jokela J. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;86:1213–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2482-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Smith RA, Barbosa J, Blum CL, Bobko MA, Caringal YV, Dally R, Johnson JS, Katz ME, Kennure N, Kingery-Wood J, Lee W, Lowinger TB, Lyons J, Marsh V, Rogers DH, Swartz S, Walling T, Wild H. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:2775–2778. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Davis MR, Singh EK, Wahyudi H, Alexander LD, Kunicki J, Nazarova LA, Fairweather KA, Giltrap AM, Jolliffe KA, McAlpine SR. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:1029–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.11.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Singh E, Ramsey DM, McAlpine SR. Org Lett. 2012;14:1198–1201. doi: 10.1021/ol203290n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biron E, Chatterjee J, Kessler H. Organic Letters. 2006;8:2417–2420. doi: 10.1021/ol0607645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haberhauer G, Drosdow E, Oeser T, Rominger F. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:1853–1859. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma M, Cheng Y, Xu Z, Xu P, Qu H, Fang Y, Xu T, Wen L. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;42:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prince HM, Bishton MJ, Harrison SJ. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3958–3969. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Goodin S. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2008;65:S10–S15. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zeldin RK, Petruschke RA. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2004;53:4–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shin-ya K, Wierzba K, Matsuo K-i, Ohtani T, Yamada Y, Furihata K, Hayakawa Y, Seto H. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:1262–1263. doi: 10.1021/ja005780q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeldin RK, Petruschke RA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:4–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Denduluri N, Swain SM. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2008;17:423–435. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Goodin S. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2008;65:2017–2026. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hostein I, Robertson D, DiStefano F, Workman P, Andrew Clarke P. Cancer Research. 2001;61:4003–4009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giddens AC, Boshoff HIM, Franzblau SG, Barry CE, III, Copp BR. Tetrahedron Letters. 2005;46:7355–7357. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y, He K, Goldkorn A. Clinical Advances in Hematology & Oncology. 2011;9:442–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umezawa H, Maeda K, Takeuchi T, Okami Y. The Journal of antibiotics. 1966;19:200–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Matsuo Y, Kanoh K, Imagawa H, Adachi K, Nishizawa M, Shizuri Y. J Antibiot. 2007;60:256–260. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Matsuo Y, Kanoh K, Yamori T, Kasai H, Katsuta A, Adachi K, Shinya K, Shizuri Y. J Antibiot. 2007;60:251–255. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan CM, Lin CC, Kim SJ, Sellers RP, McAlpine SR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:4065–4069. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.05.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Güzeldemirci NU, Küçükbasmaci Ö. European J Med Chem. 2010;45:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marino JP, Fisher PW, Hofmann GA, Kirkpatrick RB, Janson CA, Johnson RK, Ma C, Mattern M, Meek TD, Ryan MD, Schulz C, Smith WW, Tew DG, Tomazek TA, Veber DF, Xiong WC, Yamamoto Y, Yamashita K, Yang G, Thompson SK. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3777–3785. doi: 10.1021/jm061182w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Soni B, Ranawat MSS, Rambabu, Bhandari A, Sharma S. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:2938–2942. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Aitken KM, Aitken RA. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:4384–4386. [Google Scholar]; b) Narender M, Reddy MS, Sridhar R, Nageswar YVD, RamoRao K. Tetrahedron Letters. 2005;46:5953–5955. [Google Scholar]; c) Potewar TM, Ingale SA, Srinivasan KV. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:11066–11069. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguilar E, Meyers AI. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:2473–2476. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohori H, Yamakoshi H, Tomizawa M, Shibuya M, Kakudo Y, Takahashi A, Takahashi S, Kato S, Takao T, Ishioka C, Iwabuchi Y, SH Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2563–2571. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hacker G. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:5–17. doi: 10.1007/s004410000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmore S. Toxicologic Pathology. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.