Abstract

The Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Stigmatization Model identifies how three stigma components hinder IPV help-seeking behaviors: cultural stigma, stigma internalization, and anticipated stigma. Cultural stigma highlights societal beliefs that de-legitimize people experiencing abuse. Stigma internalization involves the extent to which people come to believe that the negative stereotypes about those who experience IPV may be true of themselves. Anticipated stigma emphasizes concern about what will happen once others know about the partner abuse (e.g., rejection). We provide an integrative literature review that supports the IPV stigmatization model and its role in reducing help-seeking behaviors.

Keywords: Stigma, Intimate Partner Violence, Cultural Stigma, Anticipated Stigma, Stigma Internalization, Help-Seeking, Disclosure, Barriers

Intimate partner violence is a pervasive public health problem. Intimate partner violence refers to systematic violence used by one intimate partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner (U.S. Department of Justice, 2000). This violence can be physical, emotional, sexual, economical, or psychological (Jewkes, 2002). Social support networks are an important component in improving the mental health and safety of those who experience intimate partner violence (Coker, Smith, Thompson, McKeown, Bethea, & Davis, 2002); however, there are several barriers that can hinder help-seeking around partner abuse (Hien & Ruglass, 2009). Research has shifted from understanding these barriers on an individual level (e.g., personal characteristics that pathologize victims of intimate partner violence) to considering the sociocultural context in which intimate partner violence occurs (Grigsby & Hartman, 1997; Liang, Goodman, Tummala-Narra, & Weintraub, 2005). Although contextual barriers such as economic abuse (e.g., control over monetary resources), inadequate structural responses (e.g., non-enforcement of protection orders), and inaccessibility to appropriate resources (e.g., domestic violence shelters, mental health systems) have been considered (Grigsby & Hartman, 1997), less work has addressed how intimate partner violence stigmatization can deter help-seeking behaviors.

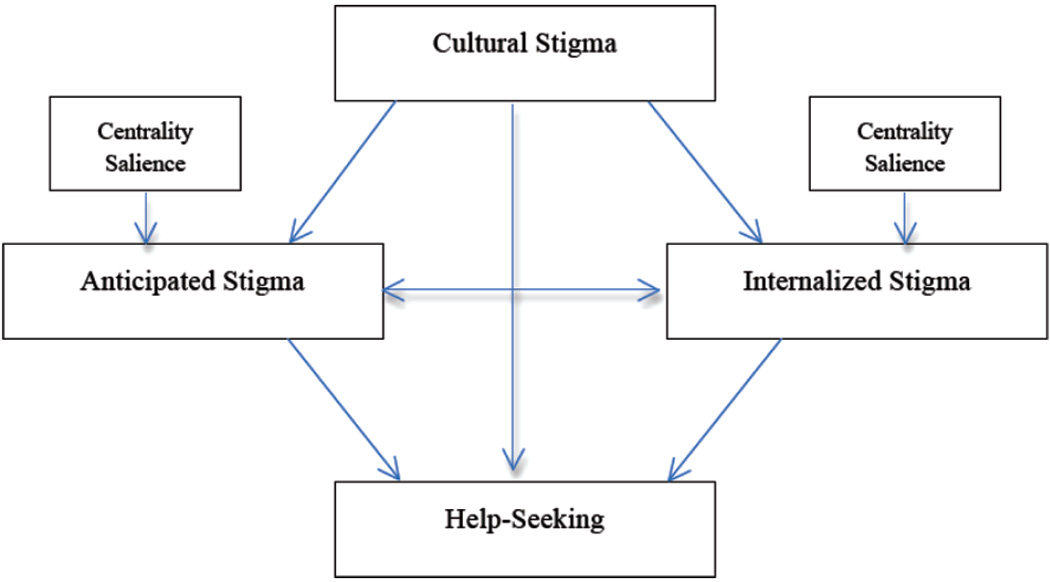

There is no conceptual framework outlining the important role intimate partner violence (IPV) stigma plays in reducing help-seeking behavior. We address this gap with the Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization model. This model considers the individual, interpersonal, and sociocultural levels in which IPV stigma can operate. On an individual level we identify two important aspects of self-stigma: Stigma internalization addresses how internalized negative beliefs about IPV as true of the self can impact help-seeking behaviors and psychological distress; anticipated stigma or concerns about what will happen once others know about the partner abuse (e.g., rejection, disapproval) affect decisions to disclose and seek help from others. Anticipated stigma works at both the individual and interpersonal level. We also consider a form of structural stigma labeled cultural stigma or ideologies that de-legitimize experiences of IPV (e.g., the belief that IPV victims provoke their own victimization) hinder help-seeking. Specifically, we highlight how negative cultural beliefs about IPV victims are embedded within and ultimately drive stigmatizing behaviors that IPV victims often experience.

We first provide a background for understanding IPV stigmatization, placing IPV within the stigma framework currently used in social psychology where it has rarely been considered. We then present the IPV stigmatization model and provide an integrative literature review of IPV research that supports the model. The IPV stigmatization model elucidates ways to conceptualize and measure the consequences of IPV stigma. Importantly, this model lends itself to developing intervention and prevention strategies that address IPV stigmatization on an individual, interpersonal, and societal level.

Definitions of Stigma

Stigma results from the possession of a socially devalued identity (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998). Goffman’s (1963) seminal work on stigma suggests that a stigmatized identity denotes a mark of failure or shame. Since Goffman’s writings on stigma, several researchers have provided frameworks for understanding mechanisms of stigmatization (Crocker et al., 1998; Jones, Farina, Hastorf, Markus, Miller, & Scott, 1984; Link & Phelan, 2001). Stigmatization occurs when power is exerted to identify, stereotype, and label differentness in socially devalued individuals, which ultimately leads to disapproval, rejection, exclusion, and discrimination (Link & Phelan, 2001).

The consequences of possessing a stigmatized identity can be costly. A recent analysis of stigma consequences revealed that greater anticipated stigma, centrality, and salience of a stigmatized identity were related to greater psychological distress (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). These findings were demonstrated among a variety of concealable stigmatized identities (i.e., socially devalued identities that can be kept hidden from others), such as mental illness, rape, abortion, and sexual orientation. However, this study did not include IPV. Empirical research on IPV stigma is scarce. Drawing on mechanisms of stigmatization (Link & Phelan, 2001), we briefly illustrate how IPV is constructed as a stigmatized identity through labeling and stereotyping that results in status loss, disapproval, and discrimination.

Understanding IPV Stigmatization

Labeling is a powerful mechanism through which stigmatization operates. Labels are socially affixed upon stigmatized identities (Link & Phelan, 2001) and can play an important role in structuring specific beliefs and behaviors towards people with stigmatized identities (Link et al., 1989). Affixing the label of “victim” to those who have experienced IPV can have important implications for IPV stigmatization. Although the victim label can absolve blame for taking part in one’s own victimization, it also constructs an image of abused individuals as trapped, passive, weak, and responsible for their own victimization (Dunn, 2005). These social constructions devalue those who have experienced IPV and equate victimization with a lack of agency.

Labels that have been affixed to stigmatized identities are associated with undesirable characteristics and negative cultural beliefs (Link & Phelan, 2001). Cultural beliefs around IPV de-legitimize individuals who have experienced partner abuse, often blaming those who have experienced IPV for their own victimization. For instance, those who experience IPV may be perceived as dependent, unassertive, helpless, depressed, and defenseless (Harrison & Esqueda, 1999). The victim-blaming component of IPV highlights a key dimension of stigma—the origin or cause of the stigmatized identity (Jones et al., 1984). Because societal perceptions of IPV often revolve around the notion that partner abuse is provoked or that IPV victims willfully stay in abusive situations, stigmatization is more likely to occur in situations where people are judged to be responsible for a stigmatizing condition. For example, victim blame and deservingness beliefs have been shown to be greater for women who violate gender role expectations, provoke their partners, and for racial minority women who are seen as less deserving of empathy (Capezza & Arriaga, 2008; Esqueda & Harrison, 2005; Kern, Libkuman, & Temple, 2007). Given the pervasiveness of these beliefs within society, those who experience partner abuse are often aware of the stigma around this identity (Williams, 2004). We will return to how this awareness of stigma can affect willingness to seek help.

The devaluation of IPV may also lead to status loss and discrimination, such that people are seen as less than whole persons and receive differential treatment based on this status loss (Link & Phelan, 2001). This discrimination can manifest in a variety of ways including negative police responding, trivialization of IPV victims, inadequate domestic violence prosecution policies, and stigmatizing responses from the justice system, family, clergy, and the community (Beaulaurier, Seff, Newman, & Dunlop, 2007; also see Liang et al., 2005 for review). In a recent series of studies, researchers found evidence that an abused woman (when in the role of a confederate and in a hypothetical situation) experienced housing discrimination, which suggests that those experiencing partner abuse may be perceived as risky tenants (Barata & Stewart, 2010). These stigmatizing behaviors and attitudes can reinforce a sense of devaluation and reduced personhood.

In summary, we have outlined how IPV is a stigmatized identity within society. People who have experienced IPV are negatively labeled, stereotypes are associated with that label, and discrimination is directed towards them. Recognizing IPV as a stigmatized identity can shed light on potential components of stigma that become the most costly throughout the help-seeking process. We now outline a model specific to IPV stigmatization and provide a review of studies supporting the model.

The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model and Help-Seeking Behaviors

Relatively few studies have explored how IPV stigmatization affects help-seeking behavior (see, Hardesty, Oswald, Khaw, & Fonseca, 2011; Liang et al., 2005; Limandri, 1989; Williams & Mickelson, 2008, for exceptions). Liang and colleagues (2005) outlined a theoretical framework – not based on stigma -- for understanding help-seeking behavior among those who experience IPV. Their recursive model suggests that those who experience IPV must recognize and define the abusive situation as intolerable, decide to seek help, and select a supportive source of help. Each stage of the help-seeking process is influenced by individual, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors. In our work, we specify how IPV stigma affects each stage of the help-seeking process. Moreover, we consider how centrality and salience of the IPV identity influences this process.

IPV is a unique stigmatized identity because it possesses both concealable and visible components. Specifically, different types of IPV (e.g., physical vs. psychological) may be more or less visible or in a specific instance, the visibility of violence can be hidden (e.g., covering bruises) or overt (e.g., loud arguments overheard by neighbors). Because IPV ranges in concealability and visibility, people experiencing IPV may face a unique set of challenges, including deep concerns about what will happen when the identity is revealed to others (Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). A crucial construct in understanding IPV and help-seeking is anticipated stigma or concern and worry about what will happen once others know about the identity. Another stigma construct that is important for those with stigmatized identities -- particularly identities where part of the stereotype is that people are personally responsible for the identity – is stigma internalization. Stigma internalization is the extent to which people come to believe (or even just consider) that the negative stereotypes about their stigmatized identity might be true of themselves. Importantly, we consider how the sociocultural context in which IPV is experienced plays a role in the stigmatization of IPV. Cultural stigma highlights how negative beliefs and stereotypes about IPV at the societal level influence the experience of IPV stigmatization at individual and interpersonal levels.

Figure 1 displays the Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model. Our model suggests that the sociocultural context in which IPV occurs can negatively impact those who experience partner abuse—increased cultural stigma around IPV heightens internalized and anticipated stigma for those experiencing partner abuse. In addition, cultural stigma may directly impact the attitudes and behaviors of people who provide support to those who experience partner abuse. The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization model also highlights how internalized stigma and anticipated stigma affect those who experience partner abuse. The experience of IPV influences people on an individual and interpersonal level; people may come to believe or even consider that the negative social constructions of IPV victims are true of themselves; people may also be concerned or worried that they will experience negative social outcomes if others knew about their stigmatized identity. The interplay between internalized stigma and anticipated stigma can be bidirectional—the greater internalized stigma people experiencing IPV have, the more they may anticipate stigma from others; however, anticipating or even experiencing stigma from others may also increase internalization of IPV stigma.

Figure 1.

The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model

Finally, our model proposes that the experience of IPV stigmatization on an individual and interpersonal level is moderated by two additional factors: centrality (i.e., the extent to which people consider an identity to be an important piece of their self-definition) and salience (i.e., the extent to which an identity is accessible or comes to mind). These factors can provide clarity in understanding the relationship between IPV stigma and help-seeking behaviors.

Support for the Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model

We now provide an integrative literature review of IPV research to support the Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization model. This review synthesizes research on IPV that highlights three stigma barriers to help-seeking—cultural stigma, stigma internalization, and anticipated stigma. Help-seeking is defined as IPV assistance (e.g., emotional support, disclosure, legal aide) sought from both informal and formal social support networks.

Method

We used three electronic databases—PsycInfo, PubMed, and Scopus—for this literature review. Published articles through Fall of 2011 were included in our search. We included the following keywords in our database search: domestic violence, intimate partner violence, partner abuse, stigma, perceived discrimination, perceived prejudice, help seeking, and barriers. We also searched the references of identified articles in order to find publications that did not appear when searching the electronic database. This snowballing procedure has been used in previous literature reviews on intimate partner violence and help-seeking (Rizo & Macy, 2011). Relevant articles were identified using the following inclusion criteria: the article was an original empirical paper, the study focused on people who have experienced IPV, the study addressed at least one of the three stigma components identified in the IPV stigmatization model, the article focused on help-seeking or help-seeking barriers, and the study was conducted in the United States. We identified 16 articles that were relevant to our literature review after applying these criteria.

Results

Results are organized by type of stigma-related barrier (anticipated stigma, stigma internalization, cultural stigma). Within each section we discuss the help-seeking outcome (recognizing IPV as a problem, deciding to seek help, choosing a source of help) that is impeded by each type of stigma barrier. Although men also experience IPV, all of the studies in our review examined help-seeking outcomes for women who have experienced IPV. A majority of the studies used qualitative methods and participants ranged in age from 18–85. Because the studies used qualitative methods, we could not use quantitative meta-analytic procedures to summarize the results.

Anticipated Stigma

Recall that anticipated stigma refers to the degree to which people fear or expect stigmatization (i.e., prejudice or discrimination) if others knew about their experiences of IPV. Ten studies outlined anticipated stigma as a critical help-seeking barrier from both formal and informal support networks (see Table 1). Anticipated stigma concerns were linked to expected devaluation when IPV was disclosed to others. Participants expressed numerous ways that this devaluation could occur.

Table 1.

Review of Articles Addressing Each Stigma Component and Impeded Help-Seeking Stage

| Study Authors | Study Objective | Method and Sample Demographics |

Stigma Component and Findings | Impeded Help-Seeking Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battaglia et al. (2003) | Identified characteristics that facilitate trust in patient-provider relationships among IPV survivors |

|

Cultural Stigma:

|

|

| Beaulaurier et al. (2005) | Addressed barriers to help-seeking for older women experiencing domestic violence |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Beaulaurier et al. (2008) | Described internal and external barriers to help-seeking for older women who experience IPV |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Chang et al. (2005) | Identified factors that increase patient comfort and willingness to seek help about IPV |

|

Anticipated Stigma:

|

|

| Dziegielewski et al. (2005) | Identified challenges that prevent or delay leaving abusive relationships |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Fugate et al. (2005) | Examined IPV help-seeking barriers from formal (police, medical attention, counseling assistance) and informal (talking to family, friend) support networks |

|

Anticipated Stigma:

|

|

| Hardesty et al. (2011) | Assessed help-seeking barriers for lesbian/bisexual mothers who were in or have left an abusive same-sex relationship |

|

Cultural Stigma:

|

|

| Lutenbacher et al. (2003) | Outlined factors that hinder and support women’s abilities to leave and stay out of abusive relationships |

|

Anticipated Stigma:

|

|

| McCauley et al. (1998) | Identified factors that facilitated disclosure to clinicians |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| McLeod et al. (2010) | Explored personal and community resources IPV survivors used when leaving an abusive relationship |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Morrison et al. (2006) | Explored help-seeking challenges African American women in abusive relationships face from informal support networks |

|

Anticipated Stigma:

|

|

| Patzel (2001) | Examined personal strengths and internal resources used by women who have left abusive relationships |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Petersen et al. (2004) | Explored women’s perceptions of motivators and barriers to IPV help-seeking |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Swanberg and Logan (2005) | Identified context associated with IPV disclosure to employers and coworkers; Examined support networks after IPV disclosure |

|

|

|

| Williams and Mickelson (2008) | Examined how perceived IPV stigma impacts willingness to seek indirect or direct help from support networks |

|

Internalized Stigma:

|

|

| Wilson et al. (2007) | Assessed health needs and barriers to healthcare among women with a history of IPV |

|

Anticipated Stigma:

|

|

In studies examining help-seeking barriers from informal support networks, participants expressed that friends and family members would not be supportive when abuse was disclosed (Beaulaurier, Seff, & Newman, 2008). Another anticipated stigma concern that was expressed in several studies was the expectation of being judged or criticized by informal support networks if participants disclosed abuse or sought help about an abusive relationship (Fugate, Landis, Riordan, Naureckas, Engel, 2005; Lutenbacher, Cohen, & Mitzel, 2003; McCauley, York, Jenckes, & Ford, 1998). Women who expressed anticipated stigma recalled negative disclosure experiences in which their family and friends reinforced the stigmatizing beliefs about IPV victims as weak or ‘stupid’ for staying in an abusive relationship (McCauley et al., 1998; Morrison, Luchok, Richter, & Parra-Medina, 2006). These experiences heightened future expectations of devaluation from informal support networks. The persecution women felt for staying in an abusive relationship made them reluctant to ask for help (Morrison et al., 2006). Moreover, the sense of uncertainty about reactions from informal support networks after disclosing abuse also shaped whether women decided to seek help and their selection of a supportive source of help (Lutenbacher et al., 2003). These studies provide evidence that anticipated stigma is an interpersonal barrier to two help-seeking stages: deciding to seek help and selecting a source of support.

Women also expressed anticipated stigma as a serious barrier to IPV help-seeking from formal social support networks (e.g., Battaglia, Finley, & Liebschutz, 2003; Chang, Decker, Moracco, et al., 2005; Fugate et al., 2005; Wilson, Silberberg, Brown, & Yaggy, 2007). For instance, women expressed fear of job loss if they disclosed experiences of abuse to employers and co-workers, which led to non-disclosure about abuse in work environments (Swanberg & Logan, 2005). Additionally, women feared that health care providers (HCPs) would devalue them and this stigmatization prevented disclosure and the facilitation of trust in the patient-HCP relationship (Battaglia et al., 2003). One participant noted, “I think that going to a hospital for domestic violence is like going to the sexually transmitted disease clinic… you feel like the doctors look at you like you’re dirty or you weren’t protecting yourself” (McCauley et al., 1998, p. 552). Another participant noted that perceiving HCPs to be judgmental “can affect what the victims’ next steps are with their abuse” (McCauley et al., 1998, p. 553). Participants acknowledged that anticipating stigma could stem from verbal instances of stigmatization but also non-verbal behaviors (e.g., gestures, looks, etc.) that imply feelings of anxiety, judgment, or impatience (Battaglia, et al., 2003). When people experiencing IPV are interacting with HCPs, they may be particularly alert to subtle cues in nonverbal communication that convey a lack of caring. Perceiving these cues, in turn, may lead people experiencing IPV to anticipate stigma and be reluctant to disclose about their abuse or seek help about IPV.

Women’s experiences of anticipated stigma were replete throughout the articles included in this review and provide support that anticipated stigma heightens a sense of shame and secrecy around IPV (Beaulaurier, Seff, Newman, & Dunlop, 2005). Whereas disclosure can have positive outcomes, the heart of anticipated stigma lies in the fear of not knowing whether stigmatization will occur if others knew about one’s experiences of abuse. This fear is a key component in preventing women from seeking help and disclosing about their abuse. Our literature review also provided evidence that anticipated stigma is more complex when those experiencing abuse do not fit into societal expectations of IPV victims. For instance, women experiencing IPV in same-sex relationships expressed anticipating intersectional stigma for being in an abusive relationship and being a lesbian (Hardesty et al., 2011). Thus, anticipating stigma from support networks was a combination of devaluation based on IPV and one’s sexuality. Women who anticipated intersectional stigma were more likely to use covert help-seeking tactics by seeking help without disclosing that they were in an abusive same-sex relationship. Additionally, women who were closeted, unsure, or ashamed about their sexuality were more likely to try and solve IPV on their own (Hardesty et al., 2011). In a sample of older women experiencing partner abuse (Beaulaurier et al., 2008), women expressed being ridiculed from formal support networks if they sought out IPV services that were primarily geared toward younger women. These findings indicate that anticipated stigma can thwart IPV help-seeking and may be complicated further by possessing other stigmatized identities.

Stigma Internalization

Stigma internalization, a form of self-stigma, is the extent to which people internalize negative IPV beliefs. These beliefs can be related to constructions of IPV victims as weak and helpless or devaluations of IPV as shameful. This review identified social contexts (e.g., a negative or judgmental disclosure event, psychological abuse from partner, etc.) that contribute to internalization of these stigmatizing beliefs as true of the self. Thus, when people actively seek-help for IPV, they may be met with stigmatization that magnifies victim-blaming beliefs, thereby heightening psychological and emotional distress.

Across 11 studies, women expressed self-blame, shame, and embarrassment about partner abuse (Table 1). These manifestations of stigma internalization were frequently mentioned as barriers to help-seeking from informal and formal support networks (e.g., Patzel, 2001; Petersen, Moracco, Goldstein, & Clark, 2004; Wilson et al., 2007). Dziegielewski, Campbell, and Turnage (2005) found that guilt and self-blame were among the top five challenges to leaving an abusive relationship for women who had a desire to leave but were not sure that they could as opposed to women who had an exit plan and those who did not expect to return to an abusive relationship. In addition, participants suggested that shame and embarrassment from physical and psychological abuse lowered their self-efficacy in seeking care and their sense of self-worth (Wilson et al., 2007). These findings suggest that stigma internalization can hinder decisions to seek help by lowering self-worth and perceived self-efficacy, particularly when women are contemplating leaving an abusive relationship.

In the only study using quantitative methods to examine the relationship between IPV stigma and help-seeking, Williams and Mickelson (2008) found that feelings of shame, embarrassment, and deviance for being in an abusive relationship were strongly and positively correlated with indirect support seeking (defined as help-seeking strategies that allow those with a stigmatized identity to seek help while keeping their identity hidden). Although indirect help-seeking strategies may be a way to avoid negative social outcomes (e.g., rejection), these indirect strategies may be met with negative responses, such as dismissal or minimization from support networks (Williams & Mickelson, 2008). In support of this hypothesis, Williams and Mickelson (2008) found that indirect support seeking was related to unsupportive responses from informal networks.

Women also identified contexts in which stigma internalization was likely to occur. For instance, two studies found that feelings of self-blame, guilt, shame, and low self-esteem associated with women’s experiences of both physical and psychological violence were barriers to leaving an abusive relationship and accessing IPV help services (Petersen et al., 2004; Beaulaurier et al., 2005). One woman noted that psychological violence puts a woman down to the point where she feels like she is not worth anything (Beaulaurier et al., 2005) while another woman explained that the hitting and beating of physical violence reduces self-esteem and self-worth (Petersen et al., 2004). Participants also mentioned that they engaged in negative self-talk, which exacerbated feelings of worthlessness and shame (McLeod, Hays, & Chang, 2010). These examples of stigma internalization are critical barriers in the decision to seek help. As one woman noted, self-doubt and low self-esteem largely contributed to her feelings that others should not assist her and that she did not deserve the necessary resources to leave an abusive relationship (Petersen et al., 2004).

Another study identified the cognitive process of realization (i.e., insight and awareness about attributions of blame in abusive relationships) as a crucial point in breaking self-blame, guilt, and shame surrounding abuse (Patzel, 2001). One woman summarized her process of realization as “knowing something is wrong and believing it is you” to a shift in thinking that “rather than thinking it’s you all the time, you have the audacity to think it’s him” (p. 737). Shifting blame from the self to the perpetrator of abuse can be a critical point in recognizing the abuse as intolerable, thereby increasing pursuit of help-seeking resources. When women readily disclose about their abuse or seek help for IPV and are met with stigmatizing reactions from potential support networks (e.g., HCPs, family, friends, etc.), this can reactivate stigma internalization processes (Lutenbacher et al., 2003; Morrison et al., 2006) and hinder decisions to seek help.

Cultural Stigma

Cultural stigma represents societal ideologies that de-legitimize people who experience IPV. Seven studies outlined how cultural stigma impacted help-seeking behaviors (Table 1). We found that cultural stigma affected every stage of the help-seeking process. Moreover, as our model suggests, cultural stigma influenced anticipated stigma and stigma internalization.

A common help-seeking barrier was judgmental attitudes and actions from informal and formal support networks. Although judgmental attitudes and actions are also examples of experienced stigma, we felt it was necessary to highlight that it is the cultural beliefs about IPV that contribute to stigmatizing behaviors. IPV survivors recalled negative encounters with health care providers in which they felt looked down upon for abuse and other stigmatized identities, such as substance use and low socioeconomic status (Battaglia et al., 2003). Informal support networks also heightened the cultural stigma around IPV with victim-blaming responses once abuse was disclosed to them (Lutenbacher et al., 2003; Morrison et al., 2006). For example, friends and family made IPV survivors feel ‘stupid’ for staying in an abusive relationship; participants also perceived their community to hold these same stigmatizing beliefs (Morrison et al., 2006). Cultural stigma about IPV can be manifested as victim-blaming reactions and attitudes from formal and informal support networks, thereby increasing IPV survivors’ reluctance to ask for future help and shaping their selection of a source of support. These beliefs can also heighten internalized stigma when abuse is disclosed to others (Beaulaurier et al., 2008).

We also identified cultural conceptualizations of IPV that prevented recognition of abuse as a problem. IPV was described as a secret that needed to be hidden from others and dealt with as a personal matter (Beaulaurier et al., 2008; Morrison et al., 2006; Petersen et al., 2004; Swanberg & Logan, 2005). These conceptualizations of abuse as a secret and personal matter intensified women’s feelings that they were responsible for solving their abusive situations, thereby reducing help seeking from other sources. Perceptions that partner abuse was a normal occurrence in one’s community also contributed to beliefs that violence should be endured or solved in a personal way (Morrison et al., 2006). Finally, perceptions that women did not fit typical conceptualizations of an abusive relationship also hindered recognition of partner abuse as a problem. For instance, women who engaged in covert help-seeking strategies often held misconceptions about same-sex IPV (e.g., lesbian relationships should not have violence) (Hardesty et al., 2011). In addition, women noted that it was hard to identify being in an abusive relationship because of the perception that abuse involves severe injuries or perceiving that abuse only happens to certain types of women (e.g., low income) (McLeod et al., 2010). Future research should examine how types of IPV (e.g., physical, sexual, psychological) are related to anticipated and internalized stigma and how the visibility or concealability of these types of violence (or even a specific instance of violence) can hinder help-seeking.

Centrality and Salience

Centrality and salience were not a central focus of the articles we reviewed but they may be critical for understanding when people experiencing IPV face the stigma barriers proposed in our model. In previous research (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009), centrality and salience were key factors that were linked to psychological distress for people with concealable stigmatized identities. We outline how these factors can influence the relationship between IPV stigma and help-seeking behaviors.

In our review, some women did not consider IPV to be a central aspect of their identities because they did not fit typical profiles of victims or did not perceive themselves to be in what they thought of as abusive relationships (Hardesty et al., 2011; McLeod et al., 2010). Women also expressed that abuse was normalized in their communities, which lessened perceived seriousness of partner abuse (Morrison et al., 2006). It is possible that these situations can reduce the centrality of partner abuse while also minimizing the stigma around IPV. However, minimizing the stigma around partner abuse or ignoring its occurrence can potentially lower help-seeking behaviors for those experiencing abuse. Initial evidence suggests that accepting attitudes toward physical abuse is a significant predictor of abuse minimization during disclosure (Dunham & Senn, 2000).

The salience of IPV may also shape help-seeking behaviors. We previously mentioned that IPV is an identity with concealable and visible components. As such, there may be times when IPV becomes more accessible to those experiencing partner abuse. The findings of our literature review suggest that women expressed greater internalized stigma after an incident of psychological or physical abuse. It is possible that incidents of partner abuse heighten the salience of IPV, thereby increasing potential for internalized stigma.

Identity salience can also heighten anticipated stigma. For example, a woman recalled an experience in which she called in sick to work after a recent episode of physical violence that left visible bruises (McLeod et al., 2010). It is possible that this moment marked a time where IPV was salient because of visible bruises and calling in sick was a measure used to not only hide the abuse but to also avoid potential negative outcomes (e.g., devaluation by others, job loss) of having the abuse revealed. Conversely, the salience of IPV may also lead to the recognition that the abuse is intolerable and facilitate the help-seeking process.

Discussion

This paper introduced the Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model as a conceptual framework for understanding how stigma erects help-seeking barriers for people experiencing partner abuse. We reviewed 16 articles that provided support for the stigma barriers presented in our model. Our review revealed that anticipated stigma, internalized stigma, and cultural stigma were prominent barriers to help-seeking from formal and informal support networks. Moreover, these stigma barriers adversely impacted every stage of the help-seeking process from recognizing abuse as intolerable to selecting a source of support. Despite support for our model, there are some notable shortcomings that can provide fruitful avenues for future research. We now discuss these shortcomings and areas for potential research.

Mostly qualitative studies were used to understand stigma barriers to help-seeking. Although qualitative studies broaden perspectives on experiences of IPV, quantitative assessments can shed light on the strength of the relationship between IPV stigma and help-seeking. The only quantitative study in our review found a strong relationship between internalized stigma and indirect help-seeking outcomes (Williams & Mickelson, 2008), yet it is unclear how strongly correlated the other components of our model are with help-seeking behaviors. It is important for future research to address how these stigma components impact behaviors and psychological well-being.

People experiencing IPV may use more than verbal cues to assess whether an individual or environment is a safe space for disclosure. Research on reflexive and controlled reactions to individuals with perceived stigmatized identities suggests that although individuals may attempt to control their negative reactions toward those with a stigmatized identity by presenting a positive demeanor, more initial reflexive responses can indicate anxiety and avoidance (Pryor, Reeder, Yeadon, & Hesson-McInnis, 2004). More work is needed to understand how those experiencing IPV perceive these nonverbal cues (e.g., facial expressions). Breaking down these stigmatizing cues can create environments that are perceived as safe disclosure spaces. This is critical for employment and hospital environments where people may be likely to seek assistance from formal and informal support networks.

There is also a need to explore the social contexts that heighten stigma internalization. The findings from our review revealed that stigma internalization was reinforced after a negative disclosure event to a support network (Morrison et al., 2006). Moreover, women highlighted that negative disclosures about IPV made them feel invalidated and dismissed (McLeod et al., 2006). Evidence from the stigma literature suggests that negative reactions to disclosure of a stigmatized identity can heighten depression, negative mood, and anticipated negative consequences (Major, Cozzarelli, Sciacchitano, Cooper, Testa, & Muller, 1990). Although theorizing on the complexity of disclosure has emerged (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010), it is less clear how a negative disclosure event maps onto the psychological well-being and help-seeking behaviors of those concealing IPV. Work by Goodkind, Gilum, Bybee, and Sullivan (2003) indicates that physical and psychological partner violence and negative help-seeking events can dramatically impact future assistance from both formal and informal social support networks and may concurrently reduce the well-being of women experiencing IPV. Much more research is needed to understand the complex relationship between IPV disclosure, stigma internalization, anticipated stigma, and help-seeking.

It is also necessary to address the consequences of concealing IPV. Many women indicated the need to keep IPV private and that it should be kept a secret from potential support networks. Research on other concealable identities shows that concealing a stigmatized identity was related to thought suppression, which was related to more intrusive thoughts about the stigmatized identity, and consequently related to increased psychological distress (Major & Gramzow, 1999). Similar findings may emerge for IPV when it can be concealed. In instances where IPV is visible, the abuse may be minimized.

Understanding how stigma becomes a barrier to help-seeking is critical. There is a growing literature outlining the benefits of social support for those with stigmatized identities. For example, among people living with HIV/AIDS, studies have found that social support can minimize psychological distress (Catz, Gore-Felton, & McClure, 2002), and that direct forms of support seeking are related to approach forms of support (e.g., receiving solace from support networks) (Derlega, Winstead, Oldfield, & Barbee, 2003). In addition, recent research is attempting to understand the goals of disclosing a stigmatized identity, barriers to disclosure, and how individuals navigate the benefits and potential consequences of disclosure and support seeking (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010; Derlega, Winstead, & Folk-Barron; Derlega, Winstead, Greene, Serovich, & Elwood, 2002). The extant literature on stigma and support seeking can provide valuable information for understanding the process of disclosure for people who experience partner abuse. In our review of the literature, initial evidence suggests that internalized stigma related to IPV is linked to indirect support seeking—a form of help-seeking that is related to unsupportive responses from social support networks (Williams & Mickelson, 2008). More work is needed to broaden our knowledge on the relationship between stigma, disclosure, and support seeking for people experiencing IPV.

Cultural stigma around IPV may also be related to the psychological well-being and help-seeking outcomes of those experiencing abuse, particularly in contexts where abuse is normalized or encouraged to remain a secret (Berns, 1999). The effects of IPV may be further compounded for those who have multiple stigmatized identities, such as being a member of a racial or sexual minority (Morrison et al., 2006; Hardesty et al., 2011), low SES (Goodman, Smyth, Borges, & Singer, 2009; Liang et al. 2005) or an older woman experiencing partner abuse (Beaulaurier et al. 2005; Beaulaurier et al., 2007). Those with multiple stigmatized identities may experience unique challenges during the help-seeking process.

Future work should address men’s experiences with IPV stigma. The dominant discourse around intimate partner violence highlights women’s experiences as survivors of partner abuse and men as perpetrators of that abuse. Moreover, a substantial body of literature focuses on intimate partner violence in heterosexual relationships. A recent review on IPV prevalence among men suggests that men also experience partner abuse at a comparable rate to women (Nowinski & Bowen, 2012). Despite these recent statistics, research is scarce on men’s experiences of partner violence. The current paper suggests that the cultural milieu in which IPV occurs has important implications for anticipated and internalized stigma. If men are not typically considered within the dominant discourse on intimate partner violence, experiences of IPV stigmatization may be compounded with the perception that men are not victims of IPV. Thus, men may have similar concerns about anticipated and internalized stigma, but may also face additional barriers, such as legitimizing their experiences of partner abuse.

The IPV Stigmatization Model addresses cultural stigma, anticipated stigma, and stigma internalization as three stigma-related barriers to help-seeking, yet the door remains open for pursuing research on other consequences of IPV stigmatization. Stigma plays an important role in a variety of outcomes that are experienced by those with a stigmatized identity; stigma takes a toll on mental health (Miller and Myers, 1998), well-being (Quinn & Crocker, 1999), physical health (Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003), and social outcomes (Shelton, Richeson, & Salvatore, 2005). These consequences extend to people who possess both visible and concealable stigmatized identities (Frable, Platt, & Hoey, 1998; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011).

The IPV Stigmatization Model focuses on stigma as a barrier to help-seeking for those experiencing partner abuse but other factors can also influence help-seeking decisions. The literature on intimate partner violence has shed light on several help-seeking barriers, such as a lack of access to resources (e.g., domestic violence shelters, mental health systems), fear of violent repercussions from a partner, and monetary consequences (e.g., an abusive partner’s control over monetary resources) (Grigsby & Hartman, 1997; Liang et al., 2005). These are important contextual barriers that are not included in the IPV Stigmatization Model but can play an important role in shaping help-seeking decisions. Importantly, this paper presents stigma as an understudied yet critical barrier to include when understanding help-seeking decisions for those experiencing partner abuse. Moreover, the centrality and salience of IPV were presented as two important moderators for future work to consider in the relationship between IPV stigma and help-seeking. Addressing the components of stigmatization illuminated in this paper will contribute to advances in understanding IPV stigmatization.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript supported in part by a grant from the NIMH T32MH074387 to Nicole M. Overstreet and NIH R01MH82916 to Diane M. Quinn.

Contributor Information

Nicole M. Overstreet, Department of Psychology, University of Connecticut

Diane M. Quinn, Department of Psychology, University of Connecticut

References

*Denotes articles included in literature review

- *.Battaglia TA, Finley E, Liebschutz JM. Survivors of intimate partner violence speak out: Trust in the patient-provider relationship. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:617–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR, Newman FL, Dunlop B. Internal barriers to help seeking for middle-aged and older women who experience intimate partner violence. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 2005;17(3):53–74. doi: 10.1300/j084v17n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR, Newman FL. Barriers to help-seeking for older women who experience intimate partner violence: A descriptive model. Journal of Women & Aging. 2008;20:231–248. doi: 10.1080/08952840801984543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulaurier RL, Seff LR, Newman FL, Dunlop B. External barriers to help seeking for older women who experience intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:747–755. [Google Scholar]

- Berns N. “My problem and how I solved it”: Domestic violence in women’s magazines. The Sociological Quarterly. 1999;40(1):85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Catz SL, Gore-Felton C, McClure JB. Psychological distress among minority and low-income women living with HIV. Behavioral Medicine. 2002;28:53–59. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, Martin SL, Petersen R, Frasier PY. Asking about intimate partner violence: Advice from female providers to health care providers. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;59:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:236–256. doi: 10.1037/a0018193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2002;11:465–476. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele CM. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology. Boston, MA: Mcgraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Folk-Barron L. Reasons for and against disclosing HIV-seropositive test results to an intimate partner: A functional perspective. In: Petronio S, editor. Balancing the secrets of private disclosure. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN. Reasons for HIV disclosure/nondisclosure in close relationships: Testing a model of HIV-disclosure decision making. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:747–767. [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Oldfield EC, Barbee AP. Close relationships and social support in coping with HIV: A test of sensitive interaction systems theory. Aids and Behavior. 2003;7:119–129. doi: 10.1023/a:1023990107075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham K, Senn CY. Minimizing negative experiences: Women’s disclosure of partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15(3):251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JL. “Victims” and"survivors”: Emerging vocabularies of motive for"battered women who stay”. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- *.Dziegielewski SF, Campbell K, Turnage BF. Domestic violence: Focus groups from the survivors’ perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2005;11(2):9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Frable DES, Platt L, Hoey S. Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: Feeling better around similar others. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:909–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fugate M, Landis L, Riordan K, Naureckas S, Engel B. Barriers to domestic violence help-seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):290–310. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gillum TL, Bybee DI, Sullivan CM. The impact of family and friends’ reactions on the well-being of women with abusive partners. Violence Against Women. 2003;9(3):347–373. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, Singer R. When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental ealth and coping. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:306–329. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby N, Hartman BR. The barriers model: An integrated strategy for intervention with battered women. Psychotherapy. 1997;34:485–497. [Google Scholar]

- *.Hardesty JL, Oswald RF, Khaw L, Fonseca C. Lesbian/bisexual mothers and intimate partner violence: Help-seeking in the context of social and legal vulnerability. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:28–46. doi: 10.1177/1077801209347636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LA, Esqueda CW. Myths and stereotypes of actors involved in domestic violence: Implications for domestic violence culpability attributions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1999;4:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Ruglass L. Intepersonal partner violence and women in the United States: An overview of prevelance rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2009;32:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott RA. The dimensions of stigma. In: Jones EE, Scott RA, Markus H, editors. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1984. pp. 24–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, Weintraub S. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:71–84. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limandri BJ. Disclosure of stigmatizing conditions: The discloser’s perspective. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1989;3(2):69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- *.Lutenbacher M, Cohen A, Mitzel J. Do we really help? Perspectives of abused women. Public Health Nursing. 2003;20(1):56–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Cozzarelli C, Sciacchitano AM, Cooper ML, Testa M, Muller PM. Perceived social support, self-efficacy, and adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59(3):452–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Gramzow R. Abortion as stigma: Cognitive and emotional implications of concealment. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1999;77:735–745. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McCauley J, Yurk RA, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside"pandora’s box”: Abused women’s experiences with clinicians and health services. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McLeod AL, Hays DG, Chang CY. Female intimate partner violence survivors’ experiences with accessing resources. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2010;88:303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Myers AM. Compensating for prejudice: How heavyweight people(and others) control outcomes despite prejudice. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The Target’s Perspective. 1998. pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- *.Morrison KE, Luchok KJ, Richter DL, Parra-Medina D. Factors influencing help-seeking from informal networks among African American victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1493–1511. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowinski SN, Bowen E. Partner violence against heterosexual and gay men: Prevalence and correlates. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17:36–52. [Google Scholar]

- *.Patzel B. Women’s use of resources in leaving abusive relationships: A naturalistic inquiry. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2001;22:729–747. doi: 10.1080/01612840152712992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Petersen R, Moracco KE, Goldstein KM, Clark KA. Moving beyond disclosure: Women’s perspectives on barriers and motivators to seeking assistance for intimate partner violence. Women & Health. 2004;40(3):63–76. doi: 10.1300/j013v40n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JB, Reeder GD, Yeadon C, Hesson-McInnis M. A dual-process model of reactions to perceived stigma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87(4):436–452. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM. Concealable versus conspicuous stigmatized identities. In: Levin S, van Laar C, editors. Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Crocker J. When ideology hurts: Effects of belief in the Protestant ethicand feeling overweight on the psychological well-being of women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(2):402–414. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.2.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Understanding concealable stigmatized identities: The role of identity in psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2011;5:160–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rizo CF, Macy RJ. Help seeking and barriers of Hispanic partner violence survivors: A systematic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:250–264. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Richeson JA, Salvatore J. Expecting to be the target of prejudice: Implications for interethnic interactions. Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(9):1189–1202. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Swanberg JE, Logan TK. Domestic violence and employment: A qualitative study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10(1):3–17. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence (NCJ-181867) Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Kent State University; 2004. Intimate partner violence and social support seeking among low-income women: An examination of mechanisms. [Google Scholar]

- *.Williams SL, Mickelson KD. A paradox of support seeking and rejection among the stigmatized. Personal Relationships. 2008;15:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- *.Wilson KS, Silberberg MR, Brown AJ, Yaggy SD. Health needs and barriers to healthcare of women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16(10):1485–1498. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]