Abstract

Injuries frequently accumulate with age in nature. Despite the commonality of injury and the resulting impairment, there are limited experimental data for the effects of impairment on life history trade-offs between reproduction and survival in insects. We tested the effects of artificial injury and the resulting impairment on the reproductive costs and behavior of male medflies, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae). Treatment flies were impaired by amputating tarsomere segments 2–5 from the right foreleg at either eclosion or age 22 days. The effect of impairment and age on the cost of reproduction was tested by varying the timing of female availability among the treatments. Courtship behavior and copulation rates were observed hourly from age 2–5 days to determine the effects of impairment on reproductive behavior. Female access combined with the impairment reduced the life expectancy of males more than the impairment alone, whereas the health effect of amputation was influenced by age. Conversely, the risk of death due to impairment was not influenced by the males’ mating status prior to amputation. The males’ copulation success was reduced due to impairment, whereas courtship behavior was not affected. Impairment does not reduce the males’ impulse to mate but decreases the females’ receptivity to copulation, while also increasing the cost of each successful mating. Overall, minor impairment lowers the reproductive success of males and reduces longevity.

Keywords: injury, amputation, trade-offs, terminal investment hypothesis, Tephritidae, medfly, Diptera, asymetry

Introduction

Insects frequently accumulate injuries with age in nature (Burkhard et al., 2002). Defined as a dysfunction or structural abnormality, impairment often results from the accumulated damage, which leads to disability, a permanent or temporary loss of physical function (WHO, 2001; Carey et al., 2007). A frequent outcome of impairment is an increased risk of mortality and a reduction in life expectancy (Sepulveda et al., 2008; Carey et al., 2009). General life history theory predicts that an increase in the risk of mortality should lead to an increase in reproductive effort, as explained by the terminal investment hypothesis (Williams, 1966; Clutton-Brock, 1984). The terminal investment hypothesis was originally used to model the influence of age on reproductive effort, but has subsequently been applied to additional factors that may increase mortality (e.g., Velando et al., 2006). Therefore, the influence of impairment on life history strategies also includes a reproductive trade-off, in which an elevated risk of mortality leads to an increase in reproductive effort to supplement the loss of future reproductive opportunity.

Reproductive effort in male insects is conditional on age and prior mating experience (Papadopoulos et al., 1998; Liedo et al., 2002; Carey et al., 2006). There is also experimental evidence that the risk of death caused by a pathological condition may influence reproductive effort in males (Velando et al., 2006; Nielsen & Holman, 2012), a result consistent with the terminal investment hypothesis (Clutton-Brock, 1984). Because an outcome of reproductive effort in males is a loss in life expectancy (Simmons & Kotiaho, 2007; Papadopoulos et al., 2010), reproductive effort and the risk of mortality are codependent and potentially mutually affecting. Males that experience an increased risk of mortality due to impairment would be expected to augment reproductive effort, further heightening their risk of mortality and, in turn, magnifying the cost of the impairment.

Insects are susceptible to a diversity of injuries in nature, including wing damage (Higginson & Barnard, 2004; Lehnert, 2010), abdominal wounds (Cherrill & Brown, 1997), and the loss of legs, antennae (Moore et al., 1989; Cherrill & Brown, 1997), and other external structures (Stoks et al., 1999). The prevalence of injuries within a population varies across species. For example, observational data have shown that 15.1–22.5% adult bush crickets acquire two or more sublethal injuries (Cherrill & Brown, 1997), whereas 22–45% of monarch butterflies accumulate wing damage (Leong et al., 1993), and up to 90% of damsel fly larvae experience injury to caudal lamellae (Stoks, 1998). The causes of such injuries in natural settings are often unclear, but predation attempts (Ernsting & Fokkema, 1982; Cherrill & Brown, 1997; Stoks et al., 1999), mating activities (Leong et al., 1993; Alcock, 1996), and environmental factors (Moore et al., 1989; Pelletier et al., 1995) may contribute. Despite the widespread occurrence of acquired injury in nature, there is a paucity of experimental data for the effects of impairment on life history trade-offs between reproduction and survival. One method for testing for the effects of impairment in insects has been the surgical removal or manipulation of external anatomical structures (Javoiš & Tammaru, 2004; Sepulveda et al., 2008; Carey et al., 2009). The artificial damage caused by surgical amputation mirrors the types of injuries that may be encountered in a natural setting. Accordingly, responses to experimental manipulation through amputation in model systems are relevant to understanding the effects of injury and the resulting impairment on life history trade-offs in nature. Impairment induced through leg amputation reduces life span, with the total effect conditional upon leg location, the number of segments removed, and the age when the insect acquired the damage (Carey et al., 2007). Due to the increased risk of mortality associated with the surgical removal of legs (Sepulveda et al., 2008), amputation is expected to initiate a life history trade-off in favor of increased reproductive effort, as suggested by the terminal investment hypothesis.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the effects of impairment on the risk of mortality and the cost of reproduction in male Mediterranean fruit flies, Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann) (Diptera: Tephritidae), commonly referred to as the medfly. Although leg segment loss is not specifically known to occur in wild medflies, leg amputation has been observed to increase the risk of death in laboratory strains of the tephritid Anastrepha ludens (Loew) (Carey et al., 2009) and in Drosophila melanogaster Meigen (Carey et al., 2007; Sepulveda et al., 2008). Because it can be expected that male medflies will be at risk of some type of injury during their lifetime in both laboratory and natural conditions, male medflies will likely respond to the artificial impairment in a similar fashion as to more commonly acquired injury so long as the injury increases the risk of mortality. If the terminal investment hypothesis is supported, an increase in the risk of mortality caused by injury should elicit an increase in reproductive effort and increase the cost of reproduction, measured as a reduction of life expectancy. Furthermore, male reproductive behaviors are expected to reflect the heightened risk of mortality, with the anticipated increase of reproductive effort in impaired individuals expected to be expressed through greater sexual advertisement and copulation success. A secondary objective was to quantify the effect of early-life reproductive experience on late-life mortality when combined with amputation, thus testing for an interaction of two impairment sources on the cost of late-life reproduction. Mate access early in life is expected to contribute to an increased risk of mortality (Papadopoulos et al., 2010), which when combined with artificial impairment at advanced age is expected to further magnify the cost of reproduction due to reproductive effort.

Materials and methods

Medflies were obtained from a laboratory colony maintained at the USDA Pacific Basin Agriculture Research Center in Hilo, Hawaii, USA, and reared following the methods described by Vargas (1989). Because the effects of impairment on life span and reproductive ability are relatively unexplored in entomology, initial findings in laboratory strains can be used to form new hypotheses for wild populations in future studies. Additionally, the use of laboratory flies allowed for larger sample sizes than would have been allowed if wild flies were used. Laboratory-reared medflies have been used as models in many demographic studies relating to life history tradeoffs (Carey, 2003), specifically laboratory-reared medflies have been recently used to test for a male cost of reproduction (Papadopoulos et al., 2010) and to model the effects of frailty on life expectancy (Carey & Papadopoulos, 2005). Flies were sexed upon eclosion, and males were maintained as virgins until experiments began. All flies were housed under laboratory conditions (22 ± 3 °C, 60–80% r.h., and L12:D12 photoperiod, lights on at 06:00 hours) and provided ad libitum access to water and a solid diet consisting of a 3:1 mixture of sugar and yeast hydrosolysate.

Female access and impairment at eclosion

To test the effects of impairment and female access on the life expectancy of adult male medflies, 400 males were individually placed in 0.1–1 plastic cages. Following a CO2-induced anesthesia, 100 males were randomly assigned each of four treatments consisting of the following factorial combination of female access and impairment level: (1) intact non-mated, (2) intact mated, (3) impaired non-mated, and (4) impaired mated. ‘Impaired’ refers to males that experienced artificial impairment through the surgical removal of tarsomere segments 2–5 on the front right leg, whereas ‘intact’ refers to males that experienced no surgical manipulation. The males assigned to the female access treatment ‘non-mated’ remained solitarily housed for their entire life span, whereas males in the treatment ‘mated’ received a virgin female at eclosion, which was replaced with a new virgin female every 7 days.

Prior female experience and late-life impairment

A second survival assay tested the effects of prior mating condition, late-life female access, and impairment on male survival. Prior mating condition was established at eclosion, with adult males housed in group cages (30.5 × 30.5 × 30.5 cm) and maintained as either unmated, through being housed with males only (same sex), or as mated, through being housed in cages with a 2:1 female to male sex ratio (mixed sex). One thousand males were assigned to each cage condition, with four same-sex cages, each housing 250 males, and eight mixed-sex cages, each housing 125 mated males with 250 females. The effects of late-life impairment and female access were tested beginning at age 22 days, when the surviving males were removed from the group cages, anesthetized with CO2, and placed individually in 0.1–1 plastic cages. While under anesthesia, half of the surviving males from each group cage type had their front right tarsomere segments 2–5 amputated. The males were then assigned to a female access treatment, creating four late-life treatments: (1) intact solitary, (2) intact paired, (3) impaired solitary, and (4) impaired paired. Males assigned to a paired treatment received access to a newly eclosed virgin female which were replaced with new virgin females every 7 days, while males in the solitary treatments received no females. A factorial combination of the prior mating conditions early in life (same-sex or mixed-sex group cages) and the four late-life treatments resulted in a total of eight treatments.

Behavioral effects of impairment

Two separate behavioral assays were conducted to determine the effect of impairment on male reproductive behavior. The first determined the effect of impairment on male calling, which was used as a proxy for reproductive effort. Following CO2-induced anesthesia at age 0 days, males were left intact or they experienced impairment through the amputation of tarsomere segments 2–5 from the front right leg. Males were housed in 1–1 cylindrical group cages, each consisting of 10 same-treatment males. Ten replicates were tested per treatment. Sexual calling was quantified through observing the proportion of males protruding their anal sac while simultaneously flexing their plural abdominal pouches each hour (Arita & Kaneshiro, 1986). Beginning at age 2 days and ending at 5 days post eclosion, the number of males calling was recorded hourly from 08:00–15:00 hours. This method for quantifying male sexual signaling has been shown to be useful for testing the effect of age and time of day on male calling in both laboratory-reared and wild populations of medfly (Papadopoulos et al., 1998; Diamantidis et al., 2008). Males were observed between ages 2–5 days to determine what effect impairment had on sexual maturation and cumulative reproductive effort, with peak calling rates expected to be reached at age 4 days, when sexual maturation is typically reached by several laboratory strains (Papadopoulos et al., 1998; Lance et al., 2000; Liedo et al., 2002; Shelly et al., 2003). Observations did not continue beyond age 5 days due to logistical constraints, but there was not expected to be any significant increase in reproductive ability for the laboratory-reared flies beyond the observation period (Papadopoulos et al., 1998).

The effect of impairment on reproductive success was quantified through monitoring the copulation success of intact or impaired males. Impairment involved the removal of the tarsal segments 2–5 from the front right leg during CO2-induced anesthesia. Fifteen replicates were performed per treatment, each consisting of males housed in 1–1 cylindrical group cages, with 10 same-treatment males and 20 virgin females. Reproductive success was measured as the proportion of males copulating with females from 08:00 hours to 15:00 hours at ages 2–5 days.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed with the use of SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The effects of the impairment and female access treatments beginning at eclosion on the life expectancy of males were calculated with log-rank tests, and a Cox proportional hazard model was used to test the risk of mortality, measured through hazard ratios, of each treatment against the control (intact unmated). Further log-rank tests tested the effect of prior female experience in the group cages and the late-life effects of female access and impairment on the life expectancy of males following removal from the group cages, whereas a second Cox proportional hazard model tested the effect of each variable and their interactions on the risk of mortality for males. Two separate repeated-measures ANOVA were performed to test the between-factor effects of impairment and age and the within-subject effects of time on calling and copulation behavior. The hourly percentage of males calling or mating was used as the repeated measure, and interactions were tested between each factor with time. Greenhouse-Geisser Epsilon-corrected P-values were used to test for significance of the within-subject effects. Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test was used to detect age specific differences in the average hourly proportion of calling and copulating males.

Results

Female access and impairment at eclosion

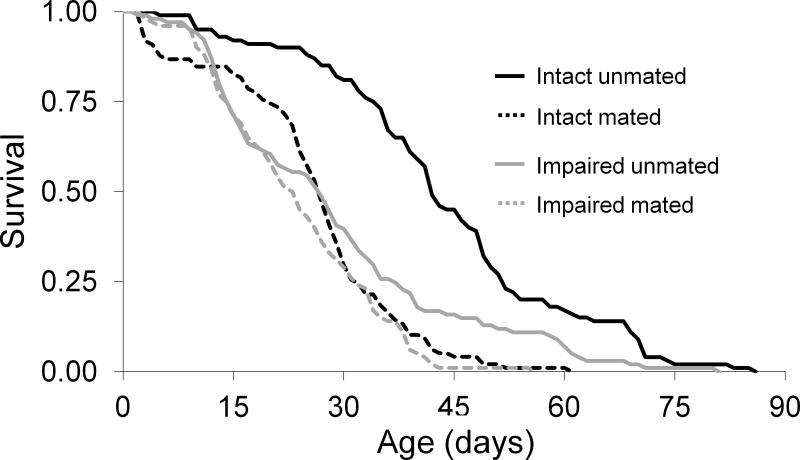

Life expectancy of intact unmated males was 44.3 days. Female access reduced the life expectancy of intact males by 18.6 days (log-rank test: χ2 = 29.53, d.f. = 1, P<0.001) (Table 1, Figure 1), and increased the risk of mortality 3.1-fold relative to unmated males (Table 1). Life expectancy of amputated unmated males was reduced by 15.3 days (χ2 = 70.60, d.f. = 1, P<0.001), whereas the risk of mortality was 2.2-fold greater than in intact unmated males (Table 1). Life expectancy of males with leg amputations and female access was reduced by 20.4 days (χ2 = 97.46, d.f. = 1, P<0.001), whereas mortality increased 3.8-fold relative to intact unmated males (Table 1). Impaired mated males experienced a 5.1 day reduction in life span compared to impaired unmated males (χ2 = 8.40, d.f. = 1, P<0.004), whereas the life expectancies of intact mated and amputated mated males were not different (χ2 =2.30, d.f. = 1, P = 0.13) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of treatment type on average (± SE) and maximum (Max) life span (days) of male medflies. Estimate (± SE) and hazard ratio were calculated from the Cox proportional hazards model for the mated and impairment treatments. Intact unmated males formed the baseline

| Treatment | Life span | Max | Estimate | Hazard ratio | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact unmated (baseline) | 44.30 ± 1.77a | 86 | - | - | - |

| Intact mated | 25.76 ± 1.21b | 61 | 1.14 ± 0.15 | 3.14 | 56.21*** |

| Impaired unmated | 29.00 ± 1.67c | 81 | 0.78 ± 0.14 | 2.18 | 29.39*** |

| Impaired mated | 23.87 ± 1.10b | 56 | 1.34 ± 0.15 | 3.83 | 75.59*** |

P<0.001.

Averages within a column followed by different letters are significantly different (Log-rank test, pair-wise comparison: P<0.05).

Figure 1.

Daily survival of male medflies in each treatment when impairment and female access treatments began at eclosion.

Prior female experience and late-life impairment

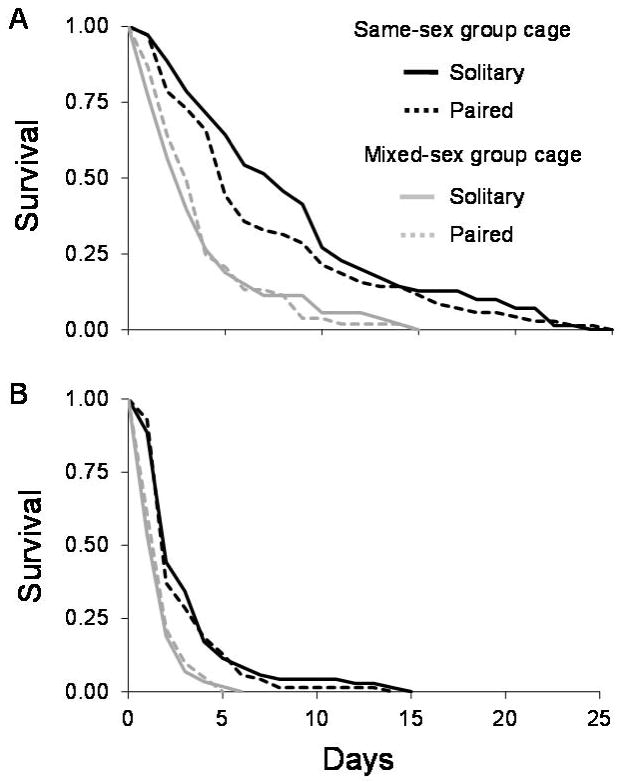

The probability of males surviving to age 22 days was 0.61 in the same-sex cages and 0.24 in the mixed-sex cages. The post-group cage life expectancy of males from the mixed-sex cages was 2.8 days less than that of males from the same-sex cages (log-rank test: χ2 = 74.57, d.f. = 1, P<0.001) (Figure 2, Table 2). After being removed from the group cages, the risk of mortality of males from the mixed-sex cages was 2.3-fold greater than that of males from the same-sex group cages (Table 2, Figure 2). The post-group cage life expectancy of males was not affected by the late-life female access, regardless of the prior mating conditions in the group cages (χ2 = 1.29, d.f. = 1, P = 0.26) (Table 2). Amputation reduced life expectancy for all males after they were removed from the group cages (χ2 = 107.7, d.f. = 1, P<0.001), whereas the risk of mortality of amputated males increased 2.5 fold (Table 2). The effect of amputation on the post-group cage life expectancy and mortality was not influenced by the prior mating conditions in the group cages.

Figure 2.

Daily survival of intact (A) and impaired (B) male medflies beginning at age 22 days (late life conditions), following the removal from the group cages and represented as day 0. The black lines represent the males housed in the all-male group cages during the early-life conditions, from ages 0–21 days (same-sex group cage). The gray lines represent males housed in the mixed sex group cages for the early-life conditions (mixed-sex group cage). The solid lines represent the treatments that were housed solitarily beginning at age 22 days (Solitary), while the dashed lines represent males that were paired with a female beginning at age 22 days (Paired).

Table 2.

Effect of group cage conditions (early-life mating conditions), late-life female availability (late-life mating conditions), and late-life impairment on the average (± SE) life span (days) of male medflies, calculated using log rank tests. Estimate (± SE) and hazard ratios were calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model. Hazard ratios were calculated using each ‘no’ variable as the baseline, so that the hazard ratio shows how each variable increased the risk of mortality relative to the control variables

| Variable | Life span | Estimate | Hazard ratio | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early-life mating conditions | No female access | 27.64 ± 0.30 | |||

| Female access | 24.84 ± 0.17 | 0.91 ± 0.19 | 2.48 | 23.43*** | |

| Late-life mating conditions | No female access | 26.66 ± 0.29 | |||

| Female access | 26.13 ± 0.25 | 0.20 ± 0.17 | 1.23 | 1.34 | |

| Late-life impairment level | No impairment | 28.14 ± 0.33 | |||

| Impairment | 24.67 ± 0.14 | 1.02 ± 0.18 | 2.77 | 33.27*** |

P<0.001.

Impairment and reproductive behavior

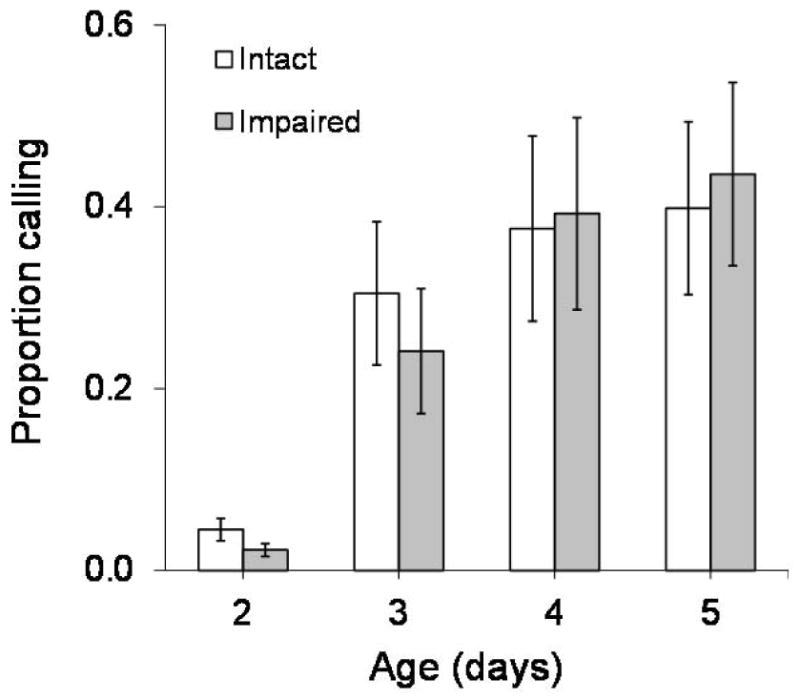

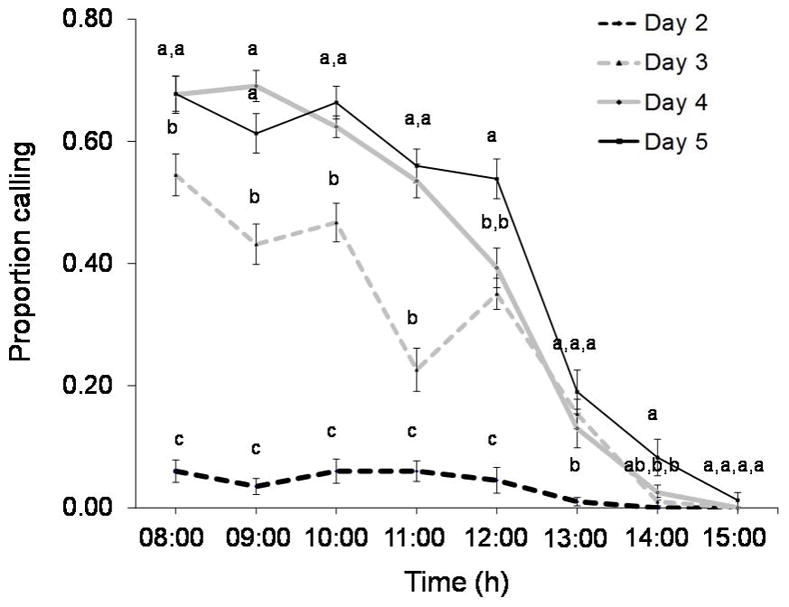

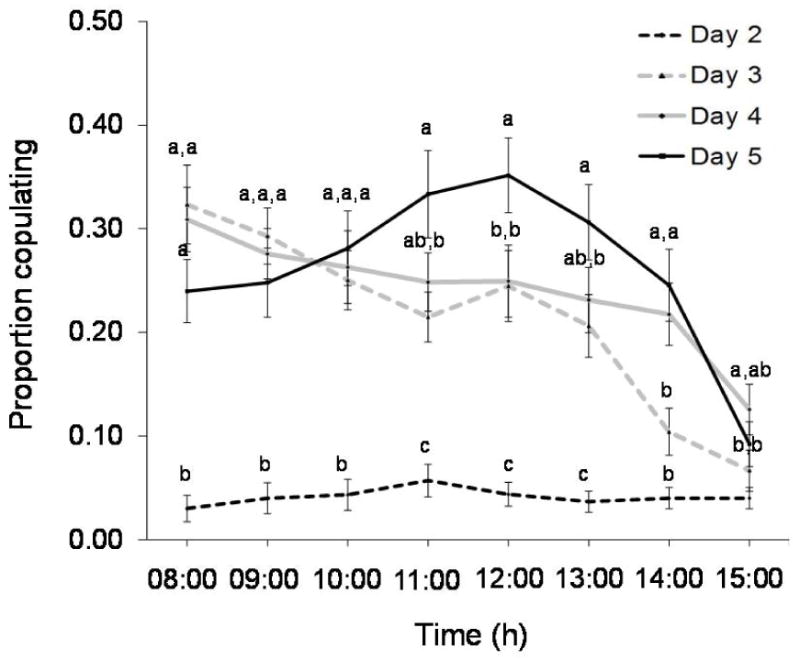

The proportion of males calling at each hour increased with age (F3,54 = 457.02, P<0.001) (Figure 3), whereas amputation had no effect (F1,54 = 0.98, P= 0.33) (Figure 3). The proportion of males calling was influenced by time (F7,378 = 293.46, P<0.001), with calling rates being highest around 08:00–09:00 hours. Age and time demonstrated a significant interaction (F21,378 = 31.38, P<0.001) (Table 3), and based on Tukey post-hoc comparisons, the proportion of males calling at each hour generally increased with age (Figure 4). Tukey groupings show that 2-day-old males call less frequently at each hour than do the older individuals until 14:00 hours. Finally, at 15:00 hours nearly no males signal, regardless of their age (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Average (± SE) proportion of intact and impaired male medflies calling each hour at ages 2–5 days old.

Table 3.

Effect of each factor on reproductive effort (calling) and reproductive success (copulation) of male medflies, as estimated with repeated measures ANOVA

| d.f. | Calling | Copulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| MS | F | MS | F | |||

| Between-subject effects | Impairment | 1 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 4.33 | 95.78*** |

| Age | 3 | 4.82 | 457.02*** | 2.43 | 53.61*** | |

| Impairment*age | 3 | 0.08 | 7.52*** | 0.33 | 7.30*** | |

| Within-subject effects | Hour | 7 | 3.11 | 293.46*** | 0.29 | 24.02*** |

| Hour*impairment | 7 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.03 | 2.05 | |

| Hour*age | 21 | 0.33 | 31.38*** | 0.07 | 6.03*** | |

| Hour*impairment*age | 21 | 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.02 | 1.64 | |

Significance of the within-subject effects was calculated using Greenhouse-Geisser Epsilon-corrected P-values:

P<0.001 (between-subject effects) or G-G<0.001 (within-subject effects).

Figure 4.

Average (± SE) proportion of male medflies observed calling at each hour at ages 2–5 days regardless of leg condition. Means with different letters within an hourly specific calling frequency are statistically different among age classes (Tukey’s test: P<0.05).

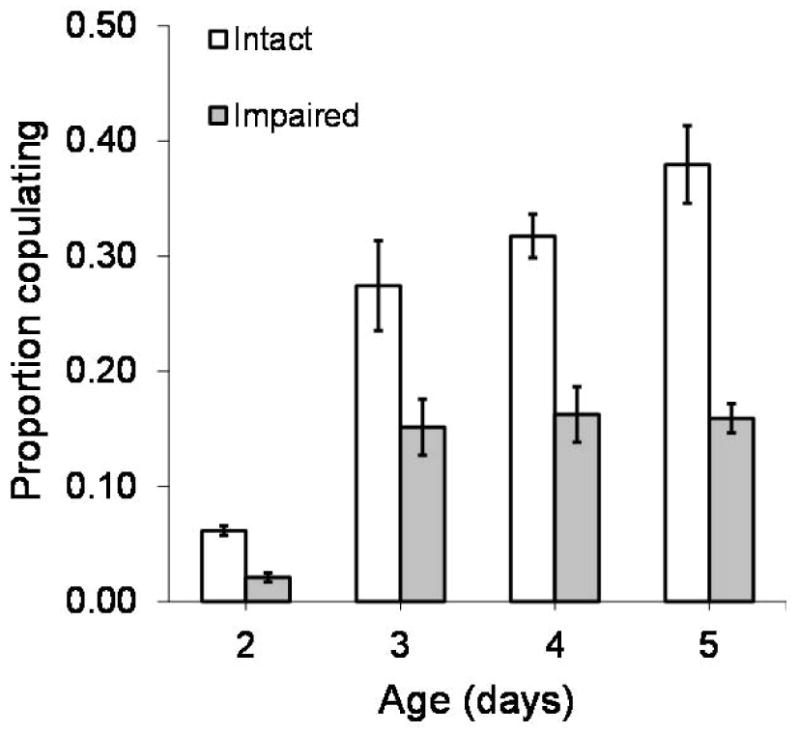

The average proportion of males copulating each hour increased with age (F3,100 = 53.61, P<0.001) (Figure 5). Amputated males did not copulate as frequently as intact males (F1,100 = 95.78, P<0.001). Age and impairment demonstrated a significant interaction (F3,100 = 7.3, P = 0.0002), in which the proportion of males copulating generally increased with age, but the success of amputated males was reduced (Figure 5). Time influenced the proportion of males copulating (F7,700 = 24.02, P<0.001), with a significant interaction found between time and age (F21,700 = 6.03, P<0.001) (Table 3). Based on Tukey post-hoc comparison, the time specific proportion of male copulating generally increases with age (Figure 6). The hourly copulation success of 2-day-old males was less than that of older individuals until 14:00 hours, at which time they exhibit copulation frequencies similar to those of 3-day-old males (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Average (± SE) proportion of intact and impaired male medflies copulating with females each hour at ages 2–5 days old.

Figure 6.

Average (± SE) proportion of male medflies observed copulating with females at each hour at ages 2–5 days regardless of leg condition. Means with different letters within an hourly specific calling frequency are statistically different among age classes (Tukey’s test: P<0.05).

Discussion

The risk of mortality was greater for males that were paired with females early in life than for males that remained unpaired. This result is consistent with the previously recorded costs of reproduction in the medfly and other male insects (Prowse & Partridge, 1997; Kotiaho & Simmons, 2003; Papadopoulos et al., 2010). Even though it is unlikely that each male mated with a female each day, as demonstrated by the average copulation rates observed in the behavioral assay here and by Whittier et al. (1994), female access still resulted in a significant loss of life span. As the males were paired with each female for 7 days, it is expected that each male initiated courtship and attempted to copulate with the females at least once (Whittier et al., 1994), suggesting that even these low rates of reproductive effort result in a cost of female access for the males. The reproductive conditions early in life constrain the post-reproductive life span, in which the female access at young ages results in increased mortality that is irreversible at advanced ages, even when males had no further interactions with females. Surprisingly, late-life female availability did not affect the risk of mortality of males at advanced ages, even when preceded by no female interactions. Therefore, the male medflies do not appear to modify reproductive effort at old ages to compensate for the missed reproductive opportunity early in life. Also, the lack of an increased risk of mortality due to female access at old ages suggests the surviving geriatric males experienced reduced reproductive ability due to reproductive senescence and/or a loss of attractiveness to females (Bonduriansky & Brassil, 2002; Papanastasiou et al., 2011).

Amputation-induced impairment increased the risk of mortality and shortened the life expectancy of males, regardless of the age when the leg segments were removed. Similar losses of life span as a result of leg amputation have been observed in D. melanogaster (Carey et al., 2007; Sepulveda et al., 2008) and A. ludens (Carey et al., 2009). Although the extent of the damage caused by amputation in this study was less than in the prior studies, in which entire limbs were excised, similar demographic responses were expressed by each species, indicating that even minor injuries have consequences leading to substantial loss of life expectancy. The nature of the disability caused by the impairment is not clear, but the loss of life span due to amputation at eclosion is not a relic of the surgical method, as evident through the nearly 2-week period of high survival following the removal of the leg segments. Therefore, the reduction in life expectancy caused by the impairment is not the result of an acute health response due to the damage but, instead, appears to be a chronic health effect that accumulates over time.

When the artificial impairment was encountered at an advanced age, amputation was characterized as having an acute health effect, expressed as an immediate and drastic reduction in post impairment survival and life span. After experiencing general senescence, the geriatric males are no longer resistant to the effects of impairment, likely due to an increase in frailty that is associated with old age in medflies (Carey & Papadopoulos, 2005). Moreover, there was no difference in the effect of amputation between males who had experienced the cost of reproduction early in life and those that did not. An increase in reproductive effort at advanced ages is unlikely for amputated males, because intact geriatric males appear to have undergone some level of reproductive senescence and avoid the life span reduction associated with access to females.

As expected, the age of the medfly and the hour of day influenced the reproductive behavior of male medflies (Prokopy & Hendrichs, 1979; Papadopoulos et al., 1998). The effect of age represents the sexual maturation of males, as recorded previously by Kaspi et al. (2002) and Papadopoulos et al. (1998). The effect of time demonstrates the circadian rhythm to reproductive behavior as observed in previous field (Prokopy & Hendrichs, 1979; Whittier et al., 1992) and laboratory trials (Papadopoulos et al., 1998; Diamantidis et al., 2008), with male calling and copulation rates following similar patterns of time dependency. Impaired males experienced reduced copulation success, but did not exhibit any changes in calling ability. As impairment did not reduce the reproductive effort of males, the loss of copulation success is likely due to a loss of function of the front legs, as well as decreased attractiveness to the females (Hunt et al., 1998). Impaired males that attempted to mount females were often observed to be quickly dislodged by the female, suggesting that the impaired males were too frail to achieve successful copulation as frequently as intact males. Additionally, based on the behavioral observations, impaired males that would initiate courtship behaviors were often rejected by the female. Previous investigations have demonstrated that symmetry in secondary sexual structures are used by female medflies as a measure of the fitness of a potential mate (Hunt et al., 1998, 2002), so the females may have used the injury and resulting asymmetry caused by amputation as a cue to the suitor’s health. The impairment did not disrupt the time dependency of either calling or copulation, supporting that the circadian rhythm of reproductive effort, like other daily locomotion patterns, is under genetic control in medflies (Mazzotta et al., 2005).

Even though the impaired males appear to have reduced copulation success early in life, they do not avoid the cost of reproduction. The loss of copulatory success would be expected to at least partially counterbalance the increased risk of mortality associated with female access. Instead, impaired males experience the same reduction in life expectancy due to female access as the intact males, despite the additional risk of mortality from the impairment. Because the impaired males exhibit reduced copulation success relative to intact males, and display a decreased life expectancy compared to the unmated treatments, the cost of each mating attempt appears to be magnified by the impairment.

Impairment caused by external damage does not appear to elicit an increase in reproductive effort in male medflies, as expected through the terminal investment hypothesis, but instead increases the cost of mating. It may be that injury to external structures does not provide the correct mortality cues needed to influence reproductive effort. This is supported by the loss of reproductive ability caused by injury in these male medflies and in other species (Carey et al., 2007, 2009; Sepulveda et al., 2008), whereas reproductive effort is shown to be augmented in studies where the risk of mortality is increased due to an immune response (Velando et al., 2006; Nielsen & Holman, 2012).

Overall, these results do not support the terminal investment hypothesis; instead they provide further insight to the cost of reproduction in male insects, the effect of age on reproductive effort and ability, and the influence of impairment on survival and reproductive behavior. As males engage in activities that subject them to a high risk of mortality, such as male-male competition (Gerhardt, 2002), sexual signaling (Zhang et al., 2006), territory defense (Hastings, 1989), and female searching (Bell, 1990), they are also prone to an accumulation of injury. Based on the likelihood of injury and the resulting impairment in males, we believe these results and conclusions are broadly applicable to the population dynamics of wild medflies and other species. Specifically, the principle that impairment decreases the reproductive fitness of injured individuals through a shortened life span and a loss of attractiveness to females is generally pertinent to species where sexual selection influences the evolution of the population. This loss of fitness due to injury also broadens our perspective on factors that limit reproductive fitness by demonstrating an end point to an individual’s fitness other than death. Additionally, the influence of age on the health effect of injury provides an interesting perspective on the demographics of populations, in which injury leads to a rapid removal of old males that are not likely contributing to population growth. This principle combined with the likelihood of male reproductive senescence, the marked reduction in attractiveness to females associated with age (Papanastasiou et al., 2011) and injury, and the uncertainty of the terminal investment hypothesis raise doubt in the strength of traditional hypotheses explaining male reproductive behavior and the evolution of male life histories.

Acknowledgments

We thank S Souder, R Ijima, Y Nakane, M McKenney, K Shigetani, and M Chou for logistical support and assistance in conducting experiments, as well as P Lower and F Zalom for comments on earlier drafts and editorial assistance. This research was funded through the NIH/NIA program grants P01 AG022500-01 and P01 AG08761-10.

References

- Alcock J. Male size and survival: the effects of male combat and bird predation in Dawson’s burrowing bees, Amegilladawsoni. Ecological entomology. 1996;21:309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Arita LH, Kaneshiro KY. Structure and function of the rectal epithelium and anal glands during mating behavior in the Mediterranean fruit fly male. Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 1986;26:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bell WJ. Searching behavior patterns in insects. Annual Review of Entomology. 1990;35:447–467. [Google Scholar]

- Bonduriansky R, Brassil CE. Senescence: Rapid and costly ageing in wild male flies. Nature. 2002;420:377. doi: 10.1038/420377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard DU, Ward PI, Blanckenhorn WU. Using age grading by wing injuries to estimate size-dependent adult survivorship in the field: a case study of the yellow dung fly Scathophaga stercoraria. Ecological Entomology. 2002;27:514–520. [Google Scholar]

- Carey JR. Longevity: The Biology and Demography of Life Span. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ, USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carey JR, Liedo P, Muller HG, Wang JL, Yang WJ, Molleman F. Leg impairments elicit graded and sex-specific demographic responses in the tephritid fruit fly Anastrepha ludens. Experimental Gerontology. 2009;44:541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey JR, Papadopoulos N. The medfly as a frailty model: Implications for biodemographic research. In: Carey JR, Robine J-M, Michel J-P, Christen Y, editors. Longevity and Frailty. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2005. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Carey JR, Papadopoulos N, Kouloussis N, Katsoyannos B, Müller H-G, et al. Age-specific and lifetime behavior patterns in Drosophila melanogaster and the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata. Experimental Gerontology. 2006;41:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey JR, Pinter-Wollman N, Wyman M, Müller H-G, Molleman F, Zhang N. A search for principles of disability using experimental impairment of Drosophila melanogaster. Experimental Gerontology. 2007;42:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrill A, Brown V. Sublethal injuries in a field population of the bush cricket Decticus verrucivorus (L.) (Tettigoniidae) in Southern England. Journal of Orthoptera Research. 1997;6:175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock TH. Reproductive effort and terminal investment in iteroparous animals. American Naturalist. 1984;123:212–229. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantidis AD, Papadopoulos NT, Carey JR. Medfly populations differ in diel and age patterns of sexual signalling. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2008;128:389–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsting G, Fokkema D. Antennal damage and regeneration in springtails (Collembola) in relation to predation. Netherlands Journal of zoology. 1982;33:476–484. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt HC. Sexual dimorphism. In: Pagel M, editor. Encylopedia of Evolution. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. pp. 1045–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings JM. The influence of size, age, and residency status on territory defense in male western cicada killer wasps (Sphecius grandis, Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 1989;62:363–373. [Google Scholar]

- Higginson A, Barnard C. Accumulating wing damage affects foraging decisions in honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) Ecological Entomology. 2004;29:52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MK, Crean CS, Wood RJ, Gilburn AS. Fluctuating asymmetry and sexual selection in the Mediterranean fruitfly (Diptera, Tephritidae) Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1998;64:385–396. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MK, Roux EA, Wood RJ, Gilburn AS. The effect of supra-fronto-orbital (SFO) bristle removal on male mating success in the Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) Florida Entomologist. 2002;85:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Javoiš J, Tammaru T. Reproductive decisions are sensitive to cues of life expectancy: the case of a moth. Animal Behaviour. 2004;68:249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspi R, Mossinson S, Drezner T, Kamensky B, Yuval B. Effects of larval diet on development rates and reproductive maturation of male and female Mediterranean fruit flies. Physiological Entomology. 2002;27:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kotiaho JS, Simmons LW. Longevity cost of reproduction for males but no longevity cost of mating or courtship for females in the male-dimorphic dung beetle Onthophagus binodis. Journal of Insect Physiology. 2003;49:817–822. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance DR, McInnis DO, Rendon P, Jackson CG. Courtship among sterile and wild Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) in field cages in Hawaii and Guatemala. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 2000;93:1179–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert M. New protocol for measuring Lepidoptera wing damage. Journal of the Lepidopterist’s Society. 2010;64:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Leong K, Frey D, Hamaoka D, Honma K. Wing damage in overwintering populations of monarch butterfly at two California sites. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1993;86:728–733. [Google Scholar]

- Liedo P, De Leon E, Barrios MI, Valle-Mora JF, Ibarra G. Effect of age on the mating propensity of the Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) Florida Entomologist. 2002;85:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotta GM, Sandrelli F, Zordan MA, Mason M, Benna C, et al. The clock gene period in the medfly Ceratitis capitata. Genetical Research. 2005;86:13–30. doi: 10.1017/S0016672305007664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Tabashnik BE, Stark JD. Leg autotomy: A novel mechanism of protection against insecticide poisoning in diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) Journal of Economic Entomology. 1989;82:1295–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen ML, Holman L. Terminal investment in multiple sexual signals: immune-challenged males produce more attractive pheromones. Functional Ecology. 2012;26:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos NT, Katsoyannos BI, Kouloussis NA, Economopoulos AP, Carey JR. Effect of adult age, food, and time of day on sexual calling incidence of wild and mass-reared Ceratitis capitata males. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 1998;89:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos NT, Liedo P, Muller HG, Wang JL, Molleman F, Carey JR. Cost of reproduction in male medflies: The primacy of sexual courting in extreme longevity reduction. Journal of Insect Physiology. 2010;56:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanastasiou SA, Diamantidis AD, Nakas CT, Carey JR, Papadopoulos NT. Dual reproductive cost of aging in male medflies: Dramatic decrease in mating competitiveness and gradual reduction in mating performance. Journal of Insect Physiology. 2011;57:1368–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier Y, McLeod CD, Behnard GUY. Description of sublethal injuries caused to the Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) by propane flamer treatment. Journal of Economic Entomology. 1995;88:1203–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Prokopy RJ, Hendrichs J. Mating behavior of Ceratitis capitata (Diptera, Tephritidae) on a field caged host tree. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1979;72:642–648. [Google Scholar]

- Prowse N, Partridge L. The effects of reproduction on longevity and fertility in male Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1997;43:501–512. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda S, Shojaeian P, Rauser CL, Jafari M, Mueller LD, Rose MR. Interactions between injury, stress resistance, reproduction, and aging in Drosophila melanogaster. Experimental Gerontology. 2008;43:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelly TE, Rendon P, Hernandez E, Salgado S, McInnis D, et al. Effects of diet, ginger root oil, and elevation on the mating competitiveness of male Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) from a mass-reared, genetic sexing strain in Guatemala. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2003;96:1132–1141. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-96.4.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons LW, Kotiaho JS. The effects of reproduction on courtship, fertility and longevity within and between alternative male mating tactics of the horned beetle, Onthophagus binodis. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2007;20:488–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoks R. Indirect monitoring of agonistic encounters in larvae of Lestes viridis (Odonata: Lestidae) using exuviae lamellae status. Aquatic Insects. 1998;20:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stoks R, De Block M, Van Gossum H, Valck F, Lauwers K, et al. Lethal and sublethal costs of autotomy and predator presence in damselfly larvae. Oecologia. 1999;120:87–91. doi: 10.1007/s004420050836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas RI. Mass production of Tephritid fruit flies. In: Robinson AS, Hooper G, editors. Fruit Flies, Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control. 3B. Elsevier Science Publishers; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1989. pp. 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Velando A, Drummond H, Torres R. Senescent birds redouble reproductive effort when ill: confirmation of the terminal investment hypothesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2006;273:1443–1448. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittier TS, Kaneshiro KY, Prescott LD. Mating behavior of Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in a natural environment. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1992;85:214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Whittier TS, Nam FY, Shelly TE, Kaneshiro KY. Male courtship success and female discrimination in the mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) Journal of Insect Behavior. 1994;7:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC. Natural selection, the costs of reproduction, and a refinement of Lack’s principle. American Naturalist. 1966;100:687–690. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Müller H-G, Carey JR, Papadopoulos NT. Behavioral trajectories as predictors in event history analysis: Male calling behavior forecasts medfly longevity. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2006;127:680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]