Abstract

Despite the misnomer, Marjolin's ulcers really reflect malignant degeneration arising within a pre-existing cicatrix or scar. In most instances, biopsied lesions demonstrate well-differentiated squamous cell tumors, although other epidermoid lesions are occasionally encountered. The lesions are rare and are most commonly found in the lower extremity, especially the heel and plantar foot. In light of the close association of these lesions with scarred tissues associated with various chronic lower-extremity wounds, those involved in health care delivery to these patients must be aware of Marjolin's ulcer, its manifestations and potential ramifications.

Keywords: Marjolin's ulceration, Squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Malignant degeneration of burn scars has long been recognized. In 1828, the French surgeon Jean Nicholas Marjolin described the presence of villous changes arising in a burn scar. Although he did not specifically describe this as squamous cell carcinoma, the condition still bears his name. Sometimes referred to as “warty ulcers of Marjolin,”1 Marjolin's ulcers reflect malignant degeneration arising within pre-existing scar tissue or even chronic inflammatory skin lesions. In most instances, biopsied lesions demonstrate well-differentiated squamous cell tumors but can be basal cell or melanoma. Marjolin's ulcers are most commonly found in the lower extremity,2-5 especially the plantar foot, and are rarely encountered in the digits.6 As originally presented by Marjolin, to this day the leading cause is old burn scars. The second most common association is malignant degeneration arising within osteomyelitic fistulae.7 Not uncommonly, the lesions may arise secondary to venous insufficiency ulcers or pressure ulcers. Other associations include scarring from lupus, amputation stumps, frostbite, vaccination sites, skin graft donor sites, scars, urinary fistulas, and radiation.3,4,7 Marjolin's ulcers are 3 times more likely in men than in women, with the average age of diagnosis being in the fifth decade of life.2,4,8,9 Marjolin's ulcers account for 0.05% of all squamous cell carcinomas of the lower extremity.3 Only 0.2% to 1.7% of chronic osteomyelitis cases develop into squamous cell carcinoma,8 whereas approximately 2% of burn scars undergo malignant transformation.1

The exact reason an ulcer undergoes a malignant transformation is unknown. However, there are many theories, and it is possible that multiple mechanisms are at play. Patients with depressed immune systems may be more susceptible to a malignant transformation, and this may be a potential factor in patients with underlying lupus.4,10 Chronic irritation, seen at flexion creases or repeated trauma, causes cell atypia and continuous mitotic activity of regeneration and repair leading to a malignant change.4,7,11,12 Some suggest that scar tissue has impaired immunologic reactivity to tumor cells.13 Other theories center on the relative avascularity of scar tissue as a “barrier against metastasis,” thus promoting in situ tumor growth to a critical size.4 This would help explain why these lesions are slow to develop and metastasize. Avascularity, scarring, and subsequent obliteration of the lymphatics may also interfere with lymphocyte mobility. As a result of this lymphocytic impairment, early recognition of so-called nonself malignancies ensues.14 Lymphatic obstruction within scar tissue may also inhibit or delay the delivery of tumor-specific antigens,8 thus reducing the control of tissues on cell mutations.10 When tumor cells do finally penetrate the thick scar tissue and find patent lymphatic vessels, the spread is generally quite rapid.1 Implantation of fragments (eg, from grenades) associated with blunt trauma has also been noted in association with Marjolin's ulcers, but this etiology is beyond the scope of this review.

Diagnosis

The reported latency period for the development of malignancy is between 11 and 75 years,5,15 with an average of 30 to 35 years.2,5,8,16 Some studies have, however, reported average latent periods as short as 11 years.17 Moreover, “acute” Marjolin's ulcers have been seen within 1 year of skin injury and have even been diagnosed as early as 6 weeks after injury.11,15,18 The younger the patient is at the time of injury, the longer the time it takes to undergo the malignant transformation.4

The patient's history and clinical and laboratory findings are used to diagnose Marjolin's ulcer. The classic triad of nodule formation, induration, and ulceration at a scar site suggest the diagnosis.19 Other clinical signs of a malignant ulcer include chronic ulceration greater than 3 months, rolled or everted wound margins,7,12 exuberant or excessive granulation tissue,14 foul smelling purulence,3,4,7,8 increase in size,3,8,15 bleeding on contact,3,8,12,15 crusting over,15 “epithelial pearls,”20 and pain.3,8,15 Many times Marjolin's ulcerations are rapid growing and flat, with indurated elevated margins,15 but they may also be a slow-growing exophytic papillary type, which is less severe.1,10,20

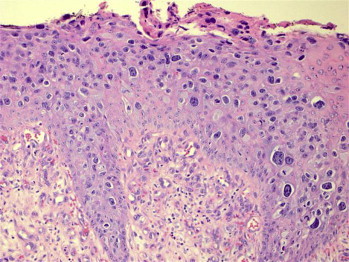

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate a 63 year old female with a clinical history of a wound that has not healed to conservative treatment in 3-4 months. The conservative treatment that was rendered was compression and topical wound dressings. In the clinical picture one can appreciate the rolled edges of the wound also the excessive granulation tissue. As a general rule, consideration should be given to biopsy of any chronic, nonhealing ulcer as this is the gold standard for the diagnosis of a malignant transformation.3,7,8,20 Punch biopsy is usually sufficient, and it should be done on any suspected portion of the wound in order to avoid a false negative.3 Some authors recommend biopsy of multiple areas such as the center and margin as well as annual biopsies on benign lesions.3,4,8 As noted before, squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type, followed by basal cell, although other types have also been reported.2,3,5,7,18,21,22 From the histopathologic perspective, spinocellular squamous cell carcinoma is the most common variety. Keratin pearl formation, lymphatic permeation, chronic inflammation, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia,2,4,11,15 and perineural infiltration are commonly seen.2,4,11 Minimal to absent keratinization is the rule, with a pseudoglandular appearance with pleomorphism. Decreased inflammatory response is noted in poorly differentiated lesions.20 Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma is also seen in Marjolin's foot ulcer, and these lesions are not uncommonly mistaken for warts.3 Immunoperoxidase stains for melanoma-associated antigen are also positive in the presence of Marjolin's ulcer.21 Figures 3–6 demonstrate the histopathology slides from the woman in the clinical picture. Biopsy results showed invasive carcinoma that is classified as a moderate to poorly differentiated carcinoma with foci of tumor necrosis.

Figure 1.

Clinical Picture. Woman aged 63 years with history of nonhealing wound for 3 to 4 months with conservative treatment including compression and topical wound dressing.

Figure 2.

Low power of view showing surface carcinoma.

Figure 3.

Biopsy of Clinical Picture. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma in situ with normal peripheral margin.

Figure 4.

Biopsy of Clinical Picture. Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows invasive carcinoma that is classified as a moderate to poorly differentiated carcinoma with foci of tumor necrosis.

Figure 5.

Low power view. Invasive nests of squamous cells surrounded by dermal stroma consisting of normal dermal cells and inflammatory cells.

Figure 6.

High power view of Figure 5.

As with most ulcers, consideration should be given to obtaining cultures from Marjolin's ulcers when clinical signs of infection are present. It is interesting to note that, whereas the most common isolate prior to carcinomatous degeneration is Staphylococcus aureus, this is not the case post degeneration,8 which suggests some inhibitory aspects of malignancy. Although lymphadenopathy may or may not be present,7 lymphatic spread is thought by some to be uncommon secondary to local destruction of the lymphatic channels.12

Many different imaging studies are used for the diagnosis of Marjolin's ulcer. Radiographs demonstrate a periosteal reaction, with lamellated being the most common, and bone destruction.2,22 Bone scans may be used to demonstrate erosions in the bone20 indicative of osteomyelitis.6

Computed tomography more thoroughly assesses bone, but the most valuable study is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) because it evaluates bone and soft tissue very well.2,22 An MRI with gadopentetate dimeglumine shows the extent of bone involvement as well as the margins to determine the best surgical option.2,13 An MRI does not demonstrate the periosteal reaction very well; however, this is irrelevant for diagnosis or treatment.22

Staging and Grading

Staging and grading generally determine prognosis. Cancerous tumors are generally staged according to the size, lymph node involvement, and metastasis. Marjolin's ulcers also follow this system, and there is a positive correlation with the duration of ulceration and chance of malignant transformation.20 The grade of the tumor can be defined as follows: grade I: more than 75% of the cells are differentiated; grade II: 25% to 75% of the cells are differentiated; grade III: less than 25% of the cells are differentiated.8,22

Treatment

Although there is no definitive treatment protocol for a confirmed Marjolin's ulcer, therapy generally involves wide local excision with skin grafting2,4,7 or amputation proximal to the lesion.7 Refinements of the above include free flaps,23 cryosurgery,20 and Mohs surgery.15 Other experimental treatments include carbon dioxide laser, intralesional interferon, and photodynamic therapy.20 Mohs surgery, in which a surgeon serves as both surgeon and pathologist in the operating room, is now considered to be the gold standard of treatments.20,24,25 In this technique, the tissue is immediately examined after excision to determine whether the margins are clear.6 The 5-year cure rate is 90% with this method, compared with 76% with surgical excision.20 Mohs surgery is, however, expensive and has a prolonged surgical time, and few doctors are adequately trained to do the procedure.20 During wide excision it is recommended to excise a margin of 2 cm of normal-appearing tissue,2,5,7,23 although some will excise a margin as narrow as 1 cm.11,20 All excised material should be sent to pathology, and if the deep margins are positive, then further resection or amputation is warranted.2,3

It is very important to cover any surgical sites with a graft or flap, generally a split-thickness skin graft or muscle flap,1,14 or to primarily close the excision site of early-stage malignancies.20 Although a previously grafted site can still turn into a malignancy,26 it has been shown that early grafting on burn sites prevents the formation of a malignancy, compared with burn sites that were allowed to heal by secondary intention.1,9 Similarly, if an old burn scar begins to ulcerate, it should be excised and grafted.1 All scar tissue is removed and a compression bandage applied in order to prevent malignant transformation.10 Perforator free flaps can be accomplished with the use of the sural, peroneal, posterior tibial, or medial plantar arteries.23 If these flaps fail, they can be recovered via a fasciocutaneous flap or skin graft.23

Perhaps the most widely accepted treatment is amputation, although some recommend a wide excision prior to amputation if amputation would impair patient function.4 Amputation is the most definitive option to treat the cancer and infection3 and is clearly advised when the bone or joint is involved.2,7 Ogawa et al. recommend amputation in grade II or III lesions and wide local excision for very small or grade I lesions.8,22 Intra-arterial infusion of methotrexate for squamous cell carcinoma20 and topical 5-fluorouracil in small in situ lesions have also been shown to be effective, but there is not much literature on these treatments.20,27 Finally, it should be noted that perioperative management includes appropriate antibiosis following culture results4 and the removal of any foreign fragments, such as those from a grenade.16

Metastasis is seen in the brain, liver, lung, kidney, and distant lymph nodes.7,15 Chest radiographs, ultrasound of the abdominal region, and computed tomography of the brain may also be routinely performed to monitor for metastasis.5,28 It is reported that 54% of the lesions that metastasize are from the lower extremity,4 and the overall risk for metastasis is 20% to 30%.11 It has been suggested that the use of cautery during excision may prevent metastatic spread into the blood stream and lymphatics,7 and lymph node irradiation or dissection decreases the risk of metastasis.8 Although the subject of some debate in the literature, sentinel lymph node biopsy is generally performed to assess lymph node involvement,2,7 whereas lymph node biopsy20 or ultrasound-guided cytologic puncture28 is reserved for palpable lymph nodes. Tumor grade and histology are other indicators for lymph node dissection.1 Some authors favor routine lymph node biopsy or irradiation in all cases of Marjolin's ulceration, since the procedure is minimally invasive.4,8 Others argue for irradiation and/or dissection of cancerous nodes or when the tumor is poorly differentiated.5,8 Most authors do agree, however, not to perform prophylactic node dissection1,5 inasmuch as data indicate no significant difference between prophylactic lymph node dissection and recurrence.8

There is considerable debate on the efficacy of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Ozek and Cankayal state radiation is indicated in patients with inoperable lymph node metastasis, grade III lesions with positive lymph nodes after node dissection, greater than 10 cm tumor diameter with positive node involvement following dissection, or lesions of the head and neck with positive nodes after dissection.29 Others have found radiation to be relatively ineffective but have had good results with intra-arterial limb perfusion.1 Nevertheless, reported results with intra-arterial limb perfusion are inconclusive.3 Overall, literature reviews support the use of adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy when resection is precluded in poor surgical candidates, in patients with metastatic spread or recurrence, or when patients refuse surgery and/or amputation.1,3,15

Prognosis

Well-differentiated lesions are less aggressive and therefore have a better prognosis.3,4 The 5-year survival rate is 40% to 69%,2,4 60% for those who underwent a wide excision, and 69% for the amputation group.4 After excision, the overall recurrence rate is 20% to 50%, with 98% of the ulcers recurring within 3 years.4 Following amputation, the rate of metastasis is 20% to 35%.8 As long as the wound margins are clean following a wide excision, there is no significant difference in recurrence between wide local excision and amputation.8 The overall 3-year survival rate is 65% to 75%,3 and 10-year survival is 34%.1 However, for those with metastasis to the lymph nodes, the 3-year survival rate significantly drops to 35% to 50%.3 If a patient survives past 3 years, there is a good prognosis since 95% of patients with metastasis present in the first 12 months.8

Conclusion

In conclusion, for ulcers that do not respond to treatment and are chronic in nature, strong consideration must be given to performing a biopsy. As a rule, normal healing should be exhibited within the first 2 to 3 weeks, and ulcers that repeatedly break down are suspicious for malignancy,20 that is, Marjolin's ulcer formation. It is important to closely monitor burn wounds and to close traumatic wounds in order to prevent excessive scarring10 and to consider malignancy in patients who seemingly acquired an ulcer from the prosthesis.28 Depending on the size and stage of the ulcer, wide excision with grafting or amputation is the mainstay of treatment. Finally, when they are diagnosed, it is imperative to monitor Marjolin's ulcers for metastasis and recurrence.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aydoğdu E., Yildirim S., Aköz T. Is surgery an effective and adequate treatment in advanced Marjolin's ulcer? Burns. 2005;31:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiang K.H., Chou A.S., Hsu Y.H. Marjolin's ulcer: MR appearance. Am J Roentgenology. 2006;186:819–820. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer T., David T., Rimareix F. Marjolin's ulcer in chronic osteomyelitis: seven cases and a review of the literature. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2007;93:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(07)90205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill B.B., Sloan D.A., Lee E.Y. Marjolin's ulcer of the foot caused by nonburn trauma. South Med J. 1996;89(7):707–710. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copcu E., Aktas A., Sismant N. Thirty-one cases of Marjolin's ulcer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:138–141. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holgado R.D., Ward S.C., Suryaprasad S.G. Squamous cell carcinoma of the hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2000;90(6):309–311. doi: 10.7547/87507315-90-6-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asuguo M., Ugare G., Ebughe G. Marjolin's ulcer: the importance of surgical management of chronic cutaneous ulcers. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(Suppl 2):29–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa B., Chen M., Marjolis J. Marjolin's ulcer arising at the elbow: a case report and literature review. Hand. 2006;1:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s11552-006-9007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soto-Dávalos B.A., Cortés-Flores A.O., Bandera-Delgado A., Luna-Ortiz K., Padilla-Rosciano A.E. Malignant neoplasm in burn scar: Marjolin's ulcer: report of two cases and review of the literature [in Spanish] Cir Cir. 2008;76(4):329–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Königová R., Rychterová V. Marjolin's ulcer. Acta Chir Plast. 2000;42(3):91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baskara A., Sikka L., Khan F., Sapanara N. Development of a Marjolin's ulcer within 9 months in a plantar pressure ulcer. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20(2):225. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatswami S., Anandan S., Krishna N., Narayanan C.D. Squamous cell carcinoma masquerading as a trophic ulcer in a patient with Hansen's disease. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2010;9(4):163–164. doi: 10.1177/1534734610389898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visuthikosol V., Boonpucknavig V., Nitiqanant P. Squamous carcinoma in scars: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;16(1):42–48. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr-Valentic M.A., Samimi K., Rohlen B.H. Marjolin's ulcer: modern analysis of an ancient problem. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(1):184–191. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181904d86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agale S.V., Kulkarni D.R., Valand A.G., Zode R.R., Grover S. Marjolin's ulcer—a diagnostic dilemma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:593–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rieger U.M., Kalbermatten D.F., Wettstein R. Marjolin's ulcer revisited—basal cell carcinoma arising from grenade fragments? Case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahla A. An overview of heel Marjolin's ulcers in the orthopedic department of Urmia University of Medical Sciences. Arch Iranian Med. 2009;12(4):405–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma R.K. Is Marjolin's ulcer always a squamous cell carcinoma? shedding some light on the old problem. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):1005. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b03a9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beachkofsky T.M., Wisco O.J., Owens N.M., Hodson D.S. Verrucous nodules on the ankle: the scaly nodules appeared over the staple sites of a previous surgery. But did one have anything to do with the other? J Fam Pract. 2009;58(8):427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enoch S., Miller D., Price P. Early diagnosis is vital in the management of squamous cell carcinomas associated with chronic non healing ulcers: a case series and review of the literature. Int Wound J. 2004;1(3):165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4801.2004.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gan B.S., Colcleugh R.G., Scilley C.G., Craig I.D. Melanoma arising in a chronic (Marjolin's) ulcer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1058–1059. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith J., Mello L.F., Neto N.C. Malignancy in chronic ulcers and scars of the leg (Marjolin's ulcer): a study of 21 patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2001;30:331–337. doi: 10.1007/s002560100355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim N.G., Lee K.S., Choi T.H. Aesthetic reconstruction of lower leg defects using a new anterolateral lower leg perforator flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:934–938. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowe D.E., Carroll R.J., Day C.L., Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976–990. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirsner R.S., Spencer J., Falanga V., Garland L.E., Kerdel F.A. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in osteomyelitis and chronic wounds: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery vs amputation. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22(12):1015–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tϋregϋn M., Nişanci M., Gϋler M. Burn scar carcinoma with longer lag period arising in previously grafted area. Burns. 1997;23(6):496–497. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Battaglia M., Treadwell T. Marjolin's ulcer. Alabama Nurse. 2008–2009;35(4):4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bloemsma G.C., Lapid O. Marjolin's ulcer in an amputation stump. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:1001–1003. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818ba0bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozek C., Cankayah R., Bilkay U., Cagdas A. Marjolin's ulcers arising in burn scars. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2001;22:384–389. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]