Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Preclinical data suggests that memantine, a noncompetitive glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptor blocker used for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, could reduce depressive and amotivated behavior occurring in the context of psychosocial stress. Therefore we examined whether memantine could reduce depressive symptoms and amotivation manifesting in older adults after a disabling medical event, thereby improving their functional recovery.

METHOD

We recruited subjects aged 60 and older who had recently suffered a disabling medical event and were admitted to a skilled nursing facility for rehabilitation. Participants with significant depressive symptoms, defined as a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score of 10 or greater, and/or significant apathy symptoms, defined as an Apathy Evaluation Scale score of 40 or greater, were randomized to memantine (10mg/d for one week, then 10mg twice daily) or placebo, for 12 weeks. We also recruited participants without depressive or apathy symptoms for naturalistic follow-up as a non-depressed comparison group. Depressive and apathy symptoms were main outcomes; functional recovery, and self-report rating of helplessness, and onset of new depressive disorders were secondary outcomes.

RESULTS

Thirty-five older adults with significant depressive and/or apathy symptoms were randomized, of whom 27 (77.1%) completed the 12 week RCT. Both groups showed reduction in depressive symptoms (but no significant reduction in apathy symptoms) and improved function. However, there were no group differences between the memantine-randomized and placebo randomized participants on any outcome.

CONCLUSION

Memantine was not associated with superior affective or functional outcome compared to placebo in medically rehabilitating older adults with depressive and apathy symptoms.

Keywords: depression, elderly, rehabilitation, memantine, motivation, participation, disability, treatment

BACKGROUND

In geriatric mental health, the glutamatergic system has been posited as a target for reducing neurodegeneration as in Alzheimer’s disease,1 with memantine being commonly used to slow cognitive decline in this context. However, another potential use of memantine’s glutamatergic mechanism of action may be for reducing depression and apathy in non-demented older adults. Older adults frequently develop depressive symptoms and apathy (or amotivation) after stressful disabling medical event (such as hip fracture).2-9 As many older adults get post-acute rehabilitative care for disabling medical events, depressive and apathy symptoms can be devastating, resulting in poorer rehabilitation outcomes and poor functional recovery.9-13

Depressive and apathy symptoms in disabled older adults are akin to similar behaviors seen in the “learned helplessness” animal model of depression in which animals are exposed to inescapable stress (e.g., repeated footshock or immobility). The characteristic response in animals is amotivation and decreased motor activity, mirroring what is seen clinically in disabled, debilitated older adults.14 A key mechanism of the stress response with respect to helplessness behaviors is glutamatergic, activated via the NMDA receptor (Hunter et al, 2003).15 In animal models, NMDA antagonists such as memantine and ketamine appear to prevent amotivated and helpless behaviors.16-21 These data are in line with work in clinical populations suggesting an antidepressant effect 22-26 and improved functional recovery27 with NMDA antagonists.

We therefore hypothesized that memantine, a noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, could reduce depressive and apathy symptoms frequently manifested in older adults after a disabling medical event and thereby improve their functional recovery, similar to pro-recovery effects reported in older adults post hip arthroplasty using ketamine.27 We conducted a double-blind placebo controlled randomized trial of memantine in 35 older patients who were admitted to a skilled nursing facility for rehabilitation after a disabling medical event and who demonstrated either mild depressive symptoms or amotivation.

The first aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility, safety and tolerability of a study of memantine in older adults participating in acute medical rehabilitation after a disabling medical event. The second aim was to evaluate changes in depressive and apathy symptoms in the memantine versus placebo randomized participants. The third aim was to investigate functional recovery and prevention of new depressive episodes in the memantine versus placebo randomized participants.

METHODS

Participants were recruited from two local skilled nursing facilities associated with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. After written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the University Institutional Review Board’s procedures, subjects were screened with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) to diagnose current and lifetime mood and other disorders,28 Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE),29 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,30 and Apathy Evaluation Scale.31 General inclusion criteria included age 60 years or older, significant functional impairment, and admission to a skilled nursing facility within the preceding 90 days with ongoing rehabilitation services (defined as 2 hours or more per day of rehabilitation therapies) for a disabling medical event (e.g., orthopedic fracture or debility). Exclusion criteria included the presence of aphasia, cognitive or behavioral impairments severe enough to prevent valid assessment (defined as a MMSE score of less than 21, diagnosis of dementia, or inability to provide informed consent); history/current psychosis or mania; current (within three months) substance or alcohol abuse or dependence; or medical inability including end-stage disease of the kidney, liver, heart, or lung as well as persons with unstable vital signs, current delirium or stroke within the past two weeks.

Participants with significant depressive symptoms, defined as a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression score ≥10,5 and/or significant apathy symptoms, defined as an Apathy Evaluation Scale score ≥40,31 were eligible to participate in the clinical trial, while those with neither significant depressive nor apathy symptoms were invited to participate as a low-risk comparison group for observation only. We used a symptomatic threshold rather than a diagnostic classification for inclusion in the clinical trial, as we anticipated that diagnostic measures of depression would be of limited value in this context32,33 and that most participants would have had a recent onset of disability and thus would not yet have full-blown mood disorders. Participants with significant depressive and/or apathy symptoms were randomized to memantine or placebo, under double-blind condition. Participants received study medication (memantine or placebo) 10 mg by mouth at bedtime for one week which was then increased to 10mg twice a day thereafter, for a total of 12 weeks. Side effects were measured by spontaneous report.

During the first 12 weeks, participants were evaluated bi-weekly using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and monthly using the Apathy Evaluation Scale and mood module of the SCID. We also examined functional recovery, using the motor subscale of the Functional Independence Measure34 (hereafter called the functional recovery score), and because the study posited a mechanism akin to learned helplessness we administered the helplessness scale from the Illness Cognitions Questionnaire (hereafter called the helplessness scale).35 Both measures were collected at baseline and 12 months later. We quantified medical burden at baseline with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics.36

To examine any long-term benefits, all participants were followed for an additional nine months after completion of the RCT and cessation of study medication (totaling 12 months of study participation). During this observational follow-up, participants were assessed monthly with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the mood module of the SCID, and at the end of this follow-up they were re-assessed with the Apathy Evaluation Scale, functional recovery score, and helplessness scale. The low-risk comparison group, while not receiving study medication, received identical assessments and follow-up.

Data Analysis

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the three groups (memantine, placebo, and low-risk comparison group) are reported in Table 1 as means with standard deviations and are compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and using Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Tukey post-hoc comparisons were performed for significant group differences. Appropriate transformations were used for non-normally distributed continuous variables.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomized subjects and low-risk comparison subjects

| Variable | Memantine (N=17) Mean (SD; range) or N (%) |

Placebo (N=18) Mean (SD; range) or N (%) |

Low-risk comparisons (N=19) Mean (SD; range) or N (%) |

Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 80.1 (9.7;62.3- 94.2) |

78.0 (9.2;60.4- 91.7) |

78.0 (9.6;60.7- 89.1) |

F(2,51)=0.29, p=0.75 |

| Gender (% female) | 82.4 (n=14) | 77.8 (n=14) | 79.0 (n=15) | Fisher Exact p=0.99 |

| Race (% Black) | 31.3 (n=5/16) | 16.7 (n=3) | 21.1 (n=4) | Fisher Exact p=0.65 |

| Mini Mental State Exam score |

27.0 (2.4; 21- 30) |

27.4 (2.3; 22- 30) n=16 |

27.5 (1.8;24-30) | F(2,49)=0.25, p=0.78 |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score |

12.5 (3.6; 3- 17) |

13.4 (3.7; 9- 23) |

4.5 (2.3; 1-8) | F(2,51)=47.75*, p<0.001 CTRL*< MEM, PBO |

| Apathy Evaluation Scale score |

34.0 (12.2; 19- 57) n=14 |

32.1 (12.2; 18-63) n=16 |

22.0 (4.3; 18-33) | F(2,46)=7.94*, p=0.001 CTRL<MEM,PBO |

| Functional recovery score | 63.6 (21.9; 20- 88) n=14 |

50.7 (19.2; 13-90) n=15 |

64.1 (15.9;32-85) | F(2,45)=2.53, p=0.09 |

| Helplessness Scale score | 12.9 (4.0; 8- 22) |

13.5 (3.9; 8- 24) n=17 |

13.5 (4.2;6-19) | F(2,50)=0.12, p=0.88 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale Category Count |

5.2 (1.7; 3-8) n=15 |

5.1 (2.1; 0-9) | 4.4 (2.8;0-9) | F(2,49)=0.76, p=0.48 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score |

11.3 (4.3; 6- 23) n=15 |

12.5 (3.6; 6- 20) n=17 |

9.7 (4.9 ; 3-18) n=18 |

F(2,47)=2.38*, p=0.10 |

data transformed for analysis

All continuous measures (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Apathy Evaluation Scale, functional recovery score, helplessness scale) were analyzed both over 12 weeks using a repeated measures mixed model to examine group, time and group-by-time interactions. An unstructured variance-covariance matrix was used. Low-risk comparison group were included on the graphs to examine whether depressed/apathetic participants improved to a level consistent with the absence of depressive and apathy symptoms. T-tests compared effect of memantine vs. placebo at 12 month follow-up. We also report frequency of onset of mood disorder diagnoses in both treatment groups.

RESULTS

From 8/2005 to 7/2008, we screened 171 older adults who were admitted for rehabilitation at a skilled nursing facility and of these, 73 (43%) had significant depressive and/or apathy symptoms and were eligible for the RCT. Of these 73, 35 (48%) consented to be randomized to memantine vs. placebo. Eligible subjects who agreed to be randomized had higher Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score, higher Apathy Evaluation Scale score, and higher MMSE score at baseline, compared to those who refused randomization (data not shown). In addition, we followed 19 participants who had no significant baseline depressive or apathy symptoms as an observation-only, low-risk comparison group.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the controls and depression/apathy participants who were randomized are shown in Table 1. Among randomized participants, the memantine and placebo groups did not differ on any baseline characteristic. Not surprisingly the randomized subjects differed on depression and apathy symptoms from the controls. In addition, an equivalent number of memantine and placebo randomized participants were receiving an antidepressant, benzodiazepine or opiate medication at baseline (data not shown). Only two subjects had a depressive diagnosis at baseline: one randomized to memantine had current major depressive disorder, and one randomized to placebo had depressive disorder not otherwise specified (minor depression).

Twenty-seven (77.1%) of the 35 randomized participants completed the 12 week RCT. Five participants died during the 12 week RCT (1 in the memantine arm and 3 in the placebo arm) and one additional participant, who had been randomized to the memantine group, died during the 9-month post-RCT observation period. Three participants withdrew consent during the RCT (1 memantine; 2 placebo). Five participants in the memantine arm had side effects (mild nausea, diarrhea, 3 with headache), as did three in the placebo arm (diarrhea, 2 with hives).

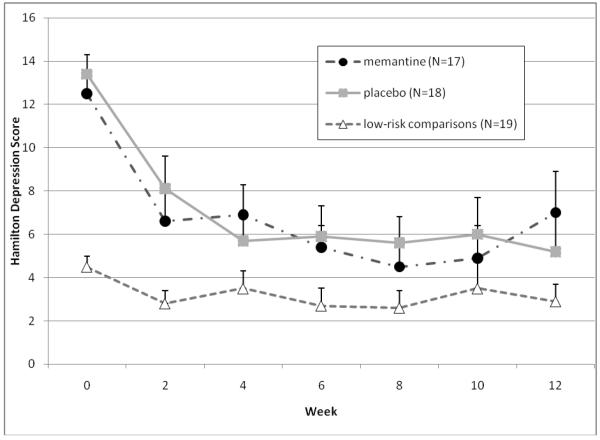

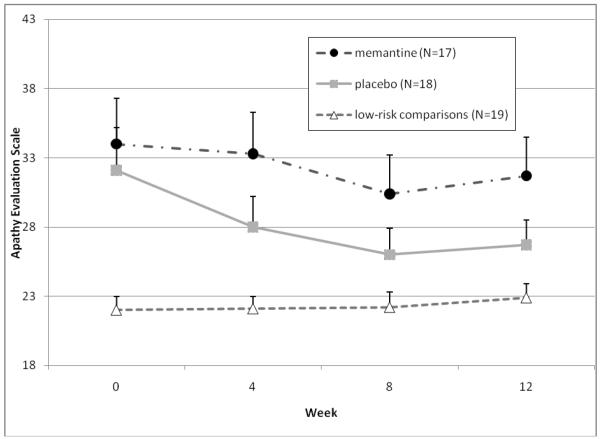

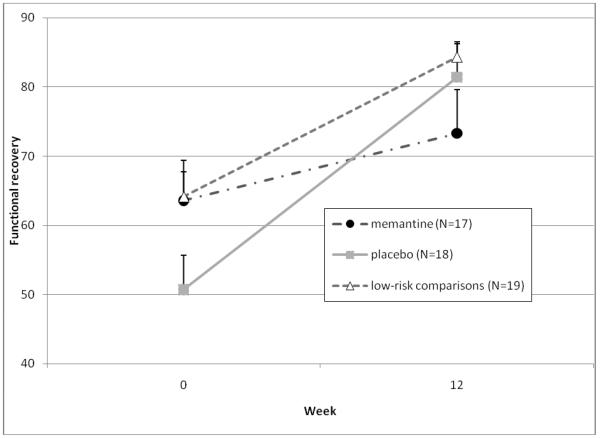

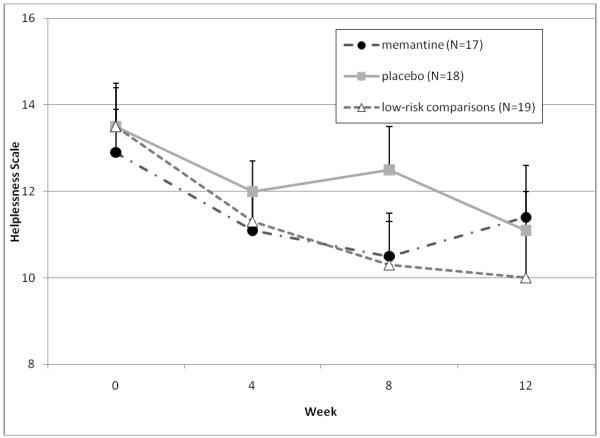

As Figure 1 shows, depressive symptoms decreased over time in all groups, but there was no difference between the memantine and placebo groups (Figure 1a), while apathy symptoms remained stable over time with no difference between the two treatment groups (Figure 1b). Additionally, there were no treatment group differences in functional recovery scores (Figure 1c) or helplessness scores (Figure 1d).

Figure 1a.

Changes in outcome measures over 12 weeks in subjects randomized to memantine vs. placebo (N=35), and in a low-risk observational comparison group (N=20) Depressive Symptoms

Note: Mixed effect model comparing only memantine and placebo-treated subjects found a significant time effect (both groups showed reduced symptoms over 12 weeks, F=18.4, df=6,33, p<0.001), no significant group effect (F=0.1, df=1,33, p=0.72), and no significant group by time interaction (both groups improved equally, F=1.0, df=6,33, p=0.42).

Figure 1b.

Changes in outcome measures over 12 weeks in subjects randomized to memantine vs. placebo (N=35), and in a low-risk observational comparison group (N=20) Apathy symptoms

Note: Mixed effect model comparing memantine and placebo-treated subjects found no significant time effect (no overall reduction in symptoms over 12 weeks, F=1.2, df=3,33, p=0.32), no significant group effect (F=0.2, df=1,33, p=0.69), and no significant group by time interaction (both groups changed equally, F=0.4, df=3,33, p=0.77).

Figure 1c.

Changes in outcome measures over 12 weeks in subjects randomized to memantine vs. placebo (N=35), and in a low-risk observational comparison group (N=20) Functional recovery scores

Note: Mixed effect model comparing memantine and placebo-treated subjects found a significant time effect (both groups showed improvement in function over 12 weeks, F=14.3, df=1,30, p<0.001), no significant group effect (F=0.2, df=1,30, p=0.66), and no significant group by time interaction (both groups improved equally, but with a trend favoring more improvement in the placebo group, F=3.7, df=1,30, p=0.06).

Figure 1d.

Changes in outcome measures over 12 weeks in subjects randomized to memantine vs. placebo (N=35), and in a low-risk observational comparison group (N=20) Helplessness Scale scores

Note: Mixed effect model comparing memantine and placebo-treated subjects found no significant time effect (no overall reduction in symptoms over 12 weeks, F=2.1, df=3,32, p=0.12), no significant group effect (F=1.2, df=1,32, p=0.29), and no significant group by time interaction (both groups changed equally, F=0.6, df=3,32, p=0.62).

Of the randomized participants who did not have a depressive diagnosis at baseline, three memantine-treated subjects developed an incident depressive episode (2 depressive disorder not otherwise specified: minor depression, at week 4, 1 major depressive disorder at week 3), as did one placebo-treated participant (major depressive disorder at week 4). Also one placebo-treated participant with minor depression at baseline evolved to major depressive disorder (at week 4).

By the end of the 12 month study which included a 9-month naturalistic observation phase, 12 participants remained in each of the memantine and placebo arms. There were no treatment group differences in terms of depressive or apathy symptoms, functional recovery or helplessness scores (data not shown). As the figures show, neither the memantine nor placebo group reached the low level of depressive or apathy symptoms seen in the low-risk comparison group (Figures 1a-b), although functional recovery and helplessness scale scores were similar (Figures 1c-d).

DISCUSSION

We carried out a pilot RCT of memantine vs. placebo for depressive and apathy symptoms in older adults receiving post-acute rehabilitation for disabling medical illness. This is a large and growing population,37 in which depression and apathy are quite pernicious, impairing quality of life and functional recovery,14 and are not easily managed by traditional treatments such as antidepressants or psychotherapy. Feasibility of the RCT appeared adequate: similar rates of early termination were seen in the memantine and placebo groups and were mostly due to participant deaths that were similar between groups. Memantine was well-tolerated, consistent with findings for its use in dementia.38 The occurrence of six deaths over 12 months in this cohort was not unexpected given the medical burden and frailty of older persons in skilled nursing facilities.

We had hypothesized that older adults receiving memantine would have greater improvements in depressive symptoms, apathy scores, and rehabilitation participation than those receiving placebo. However, we did not see any evidence of the hypothesized differences between memantine and placebo in depressive or apathy symptoms across the 12 week RCT nor in the subsequent nine-month observational phase. Similarly, we found no group differences in either helplessness scores or functional recovery, nor did we find a suggestion that treatment groups differed in number of new-onset depressive disorders. Finally, we did not see any preventive effect of memantine: similar numbers of memantine- and placebo-treated subjects developed a de novo depressive episode during the RCT (although the numbers were small). Thus, the study does not provide support for the use of memantine as a treatment or preventive intervention to reduce depressive and/or apathy symptoms in an older disabled population.

Our results are consistent with the results of Zarate et al39 who found no benefits of memantine for treatment-resistant depression. However, there are several caveats to these results. First, our failure to detect an improvement in behavioral symptoms or in functional recovery may have been secondary to the small number of participants involved. Second, some of our randomized subjects demonstrated apathy symptoms but only mild depressive symptoms, or vice versa, which could reduce the ability to detect change in these symptoms. Third, neither apathy nor helplessness scale scores showed improvement in the overall sample despite improved depressive symptoms and function; this raises the question of whether either the Apathy Evaluation Scale, or the helplessness scale, has adequate validity (e.g., sensitivity to change) for detecting treatment effects in this population. Finally, we used doses of memantine approved for use in dementia treatment (20mg daily), but it is possible that higher doses of an NMDA receptor antagonist, or more potent NMDA blockade,23 are needed for an antidepressant, anti-apathy, and pro-recovery effect. For example, beneficial effects of ketamine on functional recovery of older adults after hip arthroplasty were seen with a 24-hour ketamine infusion.27 Further studies of NMDA receptor antagonists in older adults may need to test higher doses than what is currently reported in the psychiatric literature.

Comment should be made of the difference in functional recovery between the memantine and placebo groups. The placebo group appeared to have a greater functional recovery than the memantine group (p=0.06 for treatment by time interaction) but also had a trend towards lower function at baseline, and therefore may have had more potential for improvement. Thus, it is unclear whether the results actually demonstrate worse functional recovery with memantine.

In summary, our pilot RCT did not find an antidepressant or anti-apathy effect of memantine in medically rehabilitating older adults. Other strategies are needed to improve behavioral and functional outcomes in this large and growing clinical population.

Footnotes

Clinicaltrials.gov registration: NCT00183729

Literature cited

- 1.Bleich S, Romer K, Wiltfang J, Kornhuber J. Glutamate and the glutamate receptor system: a target for drug action. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;18(Suppl 1):S33–40. doi: 10.1002/gps.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry LC, Allore HG, Bruce ML, Gill TM. Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and disability burden among older persons. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2009 Dec;64(12):1325–1332. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo JJ, Rebok GW, Tennsted S, Wadley VG, Horgas A. Linking depressive symptoms and functional disability in late life. Aging Ment Health. 2003 Nov;7(6):469–480. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001594736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C. The emergence of depressive symptoms in late life: the importance of declining health and increasing disability. J Community Health. 1990 Apr;15(2):93–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01321314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Skidmore ER, et al. Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Jan;55(1):81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ormel J, Rijsdijk FV, Sullivan M, van Sonderen E, Kempen GI. Temporal and reciprocal relationship between IADL/ADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002 Jul;57(4):P338–347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.p338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whyte EM, Mulsant BH, Vanderbilt J, Dodge HH, Ganguli M. Depression after stroke: a prospective epidemiological study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52(5):774–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodaty H, Sachdev PS, Withall A, Altendorf A, Valenzuela MJ, Lorentz L. Frequency and clinical, neuropsychological and neuroimaging correlates of apathy following stroke - the Sydney Stroke Study. Psychological Medicine. 2005 Dec;35(12):1707–1716. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Dew MA, et al. Apathy after hip fracture: a potential target for intervention to improve functional outcomes. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2009 Summer;21(3):271–278. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.21.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Dew MA, et al. Adverse effects of depression and cognitive impairment on rehabilitation participation and recovery from hip fracture. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004 May;19(5):472–478. doi: 10.1002/gps.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM, Hebel JR, Kenzora JE. Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol. 1990 May;45(3):M101–107. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mossey JM, Knott K, Craik R. The effects of persistent depressive symptoms on hip fracture recovery. J Gerontol. 1990 Sep;45(5):M163–168. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.5.m163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes J, House A. Psychiatric illness predicts poor outcome after surgery for hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Psychol Med. 2000 Jul;30(4):921–929. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, et al. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001 Spring;9(2):113–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter AM, Balleine BW, Minor TR. Helplessness and escape performance: glutamate-adenosine interactions in the frontal cortex. Behav Neurosci. 2003 Feb;117(1):123–135. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.117.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaturvedi HK, Bapna JS, Chandra D. Effect of fluvoxamine and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists on shock-induced depression in mice. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001 Apr;45(2):199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kos T, Legutko B, Danysz W, Samoriski G, Popik P. Enhancement of antidepressant-like effects but not brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA expression by the novel N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist neramexane in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006 Sep;318(3):1128–1136. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machado-Vieira R, Yuan P, Brutsche N, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009 Dec;70(12):1662–1666. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moryl E, Danysz W, Quack G. Potential antidepressive properties of amantadine, memantine and bifemelane. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993 Jun;72(6):394–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ossowska G, Klenk-Majewska B, Szymczyk G. The effect of NMDA antagonists on footshock-induced fighting behavior in chronically stressed rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997 Mar;48(1):127–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogoz Z, Skuza G, Maj J, Danysz W. Synergistic effect of uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists and antidepressant drugs in the forced swimming test in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2002 Jun;42(8):1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000 Feb 15;47(4):351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarate CA, Jr., Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006 Aug;63(8):856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preskorn SH, Baker B, Kolluri S, Menniti FS, Krams M, Landen JW. An innovative design to establish proof of concept of the antidepressant effects of the NR2B subunit selective N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist, CP-101,606, in patients with treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2008 Dec;28(6):631–637. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818a6cea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price RB, Nock MK, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Effects of intravenous ketamine on explicit and implicit measures of suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. Biological psychiatry. 2009 Sep 1;66(5):522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhonen LH, Lonnqvist J, Juva K, Alho H. Double-blind, randomized comparison of memantine and escitalopram for the treatment of major depressive disorder comorbid with alcohol dependence. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2008 Mar;69(3):392–399. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remerand F, Le Tendre C, Baud A, et al. The early and delayed analgesic effects of ketamine after total hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Anesth Analg. 2009 Dec;109(6):1963–1971. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181bdc8a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), Clinician Version: Administration Booklet. Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960 Feb;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991 Aug;38(2):143–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryant C. Anxiety and depression in old age: challenges in recognition and diagnosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010 Jun;22(4):511–513. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruce ML. Subsyndromal depression and services delivery: at a crossroad? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;18(3):189–192. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cb87f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1994 Feb;75(2):127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Lankveld W, Jongen PJ, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001 Dec;69(6):1026–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, et al. Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1992 Mar;41(3):237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secretariat of the UN [Accessed January 7, 2011];World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision. 2008 http://esa.un.org/unpp.

- 38.Jones RW. A review comparing the safety and tolerability of memantine with the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;25(6):547–553. doi: 10.1002/gps.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zarate CA, Jr., Singh JB, Quiroz JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006 Jan;163(1):153–155. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]