Abstract

Introduction:

Article 13 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) calls for a comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship (TAPS), and Article 16 calls for prohibition of tobacco sales to and by minors. Although these mandates are based on sound science, many countries have found provision implementation to be rife with challenges.

Objective:

This paper reviews the history of tobacco marketing and minor access restrictions in high-, middle-, and low-income countries, identifying past challenges and successes. We consider current challenges to FCTC implementation, how these barriers can be addressed, and what research is necessary to support such efforts. Specifically, we identify implementation and research priorities for FCTC Articles 13 and 16.

Discussion:

Although a solid evidence base underpins the FCTC’s call for TAPS bans and minor access restrictions, we know substantially less about how best to implement these restrictions. Drawing on the regulatory experiences of high-, middle-, and low-income countries, we discern several implementation and research priorities, which are organized into 4 categories: policy enactment and enforcement, human capital expertise, the effects of FCTC marketing and youth access policies, and knowledge exchange and transfer among signatories. Future research should provide detailed case studies on implementation successes and failures, as well as insights into how knowledge of successful restrictions can be translated into tobacco control policy and practice and shared among different stakeholders.

Conclusion:

Tobacco marketing surveillance, sales-to-minors compliance checks, enforcement and evaluation of restriction policies, and capacity building and knowledge transfer are likely to prove central to effective implementation.

INTRODUCTION

The tobacco industry spends billions of dollars each year promoting tobacco use. The latest Tobacco Atlas reported that in 2008 the tobacco industry spent $9.9 billion on cigarette marketing in the United States, and an additional $548 million was spent on smokeless tobacco marketing (Eriksen, Mackay, & Ross, 2012). Although there are no reliable estimates of global marketing expenditures, the World Health Organization (WHO) has speculated that expenditures run upward of tens of billions of U.S. dollars annually (WHO, 2002). Importantly, there is strong and consistent evidence that tobacco marketing activities contribute to increased tobacco use, including among youth (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2008). Given these trends, the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) mandates that every Party to the treaty “undertake a comprehensive ban of all tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship … in accordance with its constitution or constitutional principles” (Article 13; WHO, 2003). In addition, the FCTC recommends that signatories prohibit the sale of tobacco to and by minors (Article 16), as research has shown that successfully disrupting the commercial distribution of tobacco to youth reduces adolescent smoking (DiFranza, 2012).

In this paper, we begin by summarizing the recommendations of Articles 13 and 16. We then consider the tactics the tobacco industry has used to avoid marketing and youth access restrictions based on a review of the published literature, policy and implementation reports, press releases, and media coverage. We also explore the challenges associated with implementing FCTC policy, and conclude by highlighting the implementation and research priorities for Articles 13 and 16.

FCTC Article 13: Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship

Article 13 Recommendations

Article 13 of the FCTC proposes a comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship (TAPS). The article is based on sound science: an exhaustive review by the U.S. NCI (2008) found that the “total weight of evidence” from a number of studies, from a variety of research designs, and from several countries suggests that TAPS are causally related to increased tobacco use. Given this evidence base, the FCTC calls on signatories to follow several guidelines; these are summarized below and reproduced in full in Table 1.

Table 1.

FCTC Article 13: Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship and FCTC Article 16: Sales to and by Minors

| Article 13: Tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship |

| 1. Parties recognize that a comprehensive ban on advertising, promotion and sponsorship would reduce the consumption of tobacco products. |

| 2. Each Party shall, in accordance with its constitution or constitutional principles, undertake a comprehensive ban of all tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. This shall include, subject to the legal environment and technical means available to that Party, a comprehensive ban on cross-border advertising, promotion and sponsorship originating from its territory. In this respect, within the period of five years after entry into force of this Convention for that Party, each Party shall undertake appropriate legislative, executive, administrative and/or other measures and report accordingly in conformity with Article 21. |

| 3. A Party that is not in a position to undertake a comprehensive ban due to its constitution or constitutional principles shall apply restrictions on all tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. This shall include, subject to the legal environment and technical means available to that Party, restrictions or a comprehensive ban on advertising, promotion and sponsorship originating from its territory with cross-border effects. In this respect, each Party shall undertake appropriate legislative, executive, administrative and/or other measures and report accordingly in conformity with Article 21. |

| 4. As a minimum and in accordance with its constitution or constitutional principles, each Party shall: |

| (a) prohibit all forms of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship that promote a tobacco product by any means that are false, misleading or deceptive or likely to create an erroneous impression about its characteristics, health effects, hazards or emissions; |

| (b) require that health or other appropriate warnings or messages accompany all tobacco advertising, as appropriate, promotion and sponsorship; |

| (c) restrict the use of direct or indirect incentives that encourage the purchase of tobacco products by the public; |

| (d) require, if it does not have a comprehensive ban, the disclosure to relevant governmental authorities of expenditures by the tobacco industry on advertising, promotion and sponsorship not yet prohibited. Those authorities may decide to make those figures available, subject to national law, to the public and to the Conference of the Parties, pursuant to Article 21; |

| (e) undertake a comprehensive ban or, in the case of a Party that is not in a position to undertake a comprehensive ban due to its constitution or constitutional principles, restrict tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship on radio, television, print media and, as appropriate, other media, such as the internet, within a period of five years; and |

| (f) prohibit, or in the case of a Party that is not in a position to prohibit due to its constitution or constitutional principles restrict, tobacco sponsorship of international events, activities and/or participants therein. |

| 5. Parties are encouraged to implement measures beyond the obligations set out in paragraph 4. |

| 6. Parties shall cooperate in the development of technologies and other means necessary to facilitate the elimination of cross-border advertising. |

| 7. Parties which have a ban on certain forms of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship have the sovereign right to ban those forms of cross-border tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship entering their territory and to impose equal penalties as those applicable to domestic advertising, promotion and sponsorship originating from their territory in accordance with their national law. This paragraph does not endorse or approve of any particular penalty. |

| 8. Parties shall consider the elaboration of a protocol setting out appropriate measures that require international collaboration for a comprehensive ban on cross-border advertising, promotion and sponsorship. |

| Article 16: Sales to and by minors |

| 1. Each Party shall adopt and implement effective legislative, executive, administrative or other measures at the appropriate government level to prohibit the sales of tobacco products to persons under the age set by domestic law national law or eighteen. These measures may include: |

| (a) requiring that all sellers of tobacco products place a clear and prominent indicator inside their point of sale about the prohibition of tobacco sales to minors and, in case of doubt, request that each tobacco purchaser provide appropriate evidence of having reached full legal age; |

| (b) banning the sale of tobacco products in any manner by which they are directly accessible, such as store shelves; |

| (c) prohibiting the manufacture and sale of sweets, snacks, toys, or any other objects in the form of tobacco products which appeal to minors; and |

| (d) ensuring that tobacco vending machines under its jurisdiction are not accessible |

| 2. Each Party shall prohibit or promote the prohibition of the distribution of free tobacco products to the public and especially minors. |

| 3. Each Party shall endeavour to prohibit the sale of cigarettes individually or in small packets which increase the affordability of such products to minors. |

| 4. The Parties recognize that in order to increase their effectiveness, measures to prevent tobacco product sales to minors should, where appropriate, be implemented in conjunction with other provisions contained in this Convention. |

| 5. When signing, ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to the Convention or at any time thereafter, a Party may, by means of a binding written declaration, indicate its commitment to prohibit the introduction of tobacco vending machines within its jurisdiction or, as appropriate, to a total ban on tobacco vending machines. The declaration made pursuant to this Article shall be circulated by the Depositary to all Parties to the Convention. |

| 6. Each Party shall adopt and implement effective legislative, executive, administrative, or other measures, including penalties against sellers and distributors, in order to ensure compliance with the obligations contained in paragraphs 1-5 of this Article. |

| 7. Each Party should, as appropriate, adopt and implement effective legislative, executive, administrative, or other measures to prohibit the sales of tobacco products by persons under the age set by domestic law, national law or eighteen. |

Note. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (World Health Organization, 2003). Reproduced with permission from the World Health Organization.

Implement a comprehensive TAPS ban, and undertake the legislative, executive, and administrative measures necessary to implement a comprehensive ban within 5 years of the treaty’s entry into force in a given country

For signatories whose constitution does not allow for a comprehensive ban, apply restrictions on all TAPS

At a minimum, signatories should (a) prohibit all marketing that promotes tobacco products in false or misleading ways; (b) require that marketing be accompanied by health warnings; (c) restrict the use of incentives that encourage tobacco purchase; (d) require that marketing expenditures be disclosed to government authorities; (e) restrict marketing on radio, television, print, and new media (e.g., Internet and social media) within a period of 5 years; and (f) restrict tobacco sponsorship of international events, activities, and/or participants

Cooperate in international efforts to eliminate cross-border advertising (through technology development and other means), and rightfully ban any cross-border advertising entering a country’s territory that violates that country’s ban or restrictions

Importantly, Article 13 explicitly calls for a comprehensive ban, as research has shown that partial bans are not effective in reducing tobacco consumption (Blecher, 2008; NCI, 2008). Limited bans do not lower the total amount of marketing expenditure; rather, the tobacco industry simply redirects efforts to nonbanned media or other marketing activities. In contrast, there is evidence that comprehensive bans play a role in reducing tobacco consumption since such restriction precludes TAPS redirection or substitution (Blecher, 2008; NCI, 2008; Saffer & Chaloupka, 2000). That said, the treaty recognizes that constitutional constraints may render a comprehensive ban illegal. For example, the supreme courts in the United States and Canada have limited the scope of marketing bans as a result of the free speech protections that exist in both countries (NCI, 2008). For countries with such constitutional provisions, the FCTC offers recommendations for restrictions rather than outright bans.

Article 13 also draws attention to cross-border advertising and the development of tools to eliminate such advertising. This is particularly significant, and an acknowledgement of the fact that fast-evolving communication technologies such as the Internet and social media could potentially facilitate the circumvention of restrictions by any one country.

Tobacco Industry Tactics to Avoid Marketing Restrictions

Regulatory history suggests that the tobacco industry has used several strategies to evade marketing restrictions, and these tactics vary based on the level of restriction. First, in countries where restrictions are nonexistent, the tobacco industry typically maximizes marketing opportunities. For example, Indonesia—where at least 34% of adults and 12% of youth ages 13–15 smoke (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, 2012)—has been described as a “tobacco industry playground,” with cigarette advertising prevalent on television and billboards still featuring the Marlboro Man (Harris & Kilmer, 2012). According to the 2011 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, Indonesia has not enacted any TAPS restrictions, and it is the only WHO member state in Southeast Asia that has not ratified the FCTC. The country is drafting new tobacco control laws; however, not only are these laws substantially weaker than those proposed by the FCTC but industry lobbyists have worked with government officials to weaken them further (e.g., the plan to restrict billboard size to 16 m2 has been increased to 72 m2; Brown, 2012).

This industry tactic of influencing government officials to deter policy making has been used elsewhere. When Malaysia began considering advertising restrictions during the 1970s, British American Tobacco (BAT) responded quickly to slow advancing legislation. Through ongoing conversations with the Ministry of Information, as well as discussions with the deputy prime minister, the Ministry of Trade and Industry, and various media outlets, BAT managed to fend off bans in place of self-regulation (Assunta & Chapman, 2004a). In Cambodia, after years without marketing restrictions, legislation was passed in February 2011 to ban all forms of TAPS, with some restrictions on point of sale (POS) advertising. As the deadline for implementing FCTC Article 13 approached, Cambodia had formed a working group to draft the legislation; members included representatives from WHO, the country’s Ministry of Health, its National Center for Health Promotion, and others. BAT had recruited members of the working group to lobby against and weaken the proposed ban, but other group members fought to maintain the strict regulations (“Brief report on the implementation of the FCTC’s core articles in Cambodia up to March 2012,” 2012).

Similarly, industry interference has been used to thwart regulation in countries with partial bans. For example, tobacco companies have influenced the legislative process to weaken existing bans or, perhaps more commonly, prevent stronger legislation from being passed. The European Union (EU) implemented a far-reaching ban in 1998, only to have to modify it following legal challenges from member states and tobacco companies. These opponents of the ban argued that the EU Council overstepped its authority by impinging on freedom of expression—specifically, promotion of a product that is legally manufactured and distributed (Alegre, 2003; NCI, 2008). In Malaysia, self-regulation guidelines were eventually replaced with legislation. When the health ministry tried to strengthen marketing restrictions, BAT again compromised these efforts by identifying key political figures to target in negotiations (Assunta & Chapman, 2004a).

Another industry maneuver in countries with partial bans involves preemption for localities. In the United States, the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act was enacted in 1965 following the 1964 Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health, and it required cigarette packages to include specific health warnings. Although the legislation was billed as a public health victory, it also wound up supporting tobacco interests, primarily because it contained language preempting local and state governments from imposing additional warnings (Bayer, Gostin, Javitt, & Brandt, 2002). Only recently has such preemption been eliminated. In 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) was signed into law, giving the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products (FSPTCA, 2009). Crucially, the FSPTCA also preserved state and local authority to enact other, potentially more rigorous tobacco control measures (Gostin, 2009). Although FSPTCA does not ban tobacco products, it allows for significant restrictions on product marketing (see Table 2).

Table 2.

FSPTCA Provisions That Affect Tobacco Product Marketing and Sales to Minorsa

| Law restricts tobacco product advertising and marketing to youth:b |

| Limits color and design of packaging and advertisements, including audiovisual advertisementsc |

| Prohibits the sponsorship of athletic and entertainment events using tobacco brand names or logos |

| Bans the distribution of free samples of cigarettes, and restricts the distribution of free samples of smokeless tobacco products |

| Bans the distribution of free items that have tobacco brand names or logos |

| Law restricts tobacco sales to youth: |

| Requires proof of age to purchase tobacco products (federal minimum age is 18) |

| Requires face-to-face sales, with particular exemptions for vending machines and self-service displays in adult-only facilities |

| Bans the sale of packages with fewer than 20 cigarettes |

| FDA implementation authority relevant to marketing and minor access restrictions: |

| New tobacco products introduced will undergo “premarket review” unless they are exempted under FSPTCA. The review will take into consideration the health risks of the tobacco product, labeling, and manufacturing |

| FDA will convene an expert panel to examine the public health implications of raising the minimum age to purchase tobacco products |

Note. FSPTCA = Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act.

bLaw required that FDA reissue its 1996 final regulations aimed at restricting the sale and distribution of tobacco products.

cImplementation uncertain due to pending litigation.

Perhaps one of the most prevalent tactics used in the face of partial bans is moving into new marketing venues. In addition to stemming the tide of advertising restrictions, the tobacco industry in Malaysia also increased its indirect advertising initiatives. Referring to these efforts as “trademark diversification,” BAT, Philip Morris (PM), and other companies with a presence in Malaysia established companies for nontobacco products, and named each after a cigarette brand (Assunta & Chapman, 2004b). For example, BAT’s subsidiary, Brown & Williamson International Tobacco, worked with the Malaysian Tobacco Company to introduce Kent Travel and Kent Leisure Holidays, thereby linking tobacco to vacation and travel. PM sponsored several sports liked by smokers, including badminton and snooker, and established the Marlboro World of Sports television series to showcase these sponsored sporting events—thus enabling PM to maintain their presence on television despite direct advertising bans (Assunta & Chapman, 2004b).

A similar trajectory is observed in U.S. regulatory history, and again underscores the tobacco industry’s agility in circumventing bans by exploiting other marketing opportunities. Following the cigarette broadcast advertising ban in 1971, the tobacco industry shifted its focus to print media. A number of media content analyses have documented this shift, showing that there was a vast increase in the number of cigarette advertisements in magazines during the 1970s (Albright, Altman, Slater, & Maccoby, 1988; Feinberg, 1971; King, Reid, Moon, & Ringold, 1991; Warner, 1985; Weinberger, Campbell, & DuGrenier, 1981). The move to print media allowed the industry to rely increasingly on images rather than words (King et al., 1991). Companies purchased full- or double-page advertisements, prominently placed on the right-side pages and back covers of magazines (Weinberger et al., 1981). The industry also redirected resources to sponsorship marketing. Despite the broadcast ban, companies received brand exposure on television by sponsoring sports events such as auto racing (Blum, 1991; Siegel, 2001; Zwarun, 2006). Then, in 1998, the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between the attorneys general of 46U.S. states and the 5 largest tobacco companies banned cigarette billboard advertising in the United States. Again the tobacco industry redirected resources by increasing the amount of POS advertising. This included greater exterior cigarette advertising at tobacco retail locations (e.g., on the windows and doors of gas station mini-marts), as well as greater interior POS promotions (e.g., interior advertisements, sales promotions such as multipack discount offers, branded objects such as clocks and shopping baskets) (Celebucki & Diskin, 2002; Wakefield et al., 2002). Other countries have seen a similar shift toward POS advertising, as POS remains the least regulated channel for tobacco marketing (Henriksen, 2012).

The industry also has responded to stronger legislation by redirecting marketing resources to other geographic areas within a given country. When China passed the Control of Tobacco Products law in 1992—which banned print and broadcast media advertising—BAT increased communication spending by 43% to take advantage of advertising opportunities in provinces that had not yet fully embraced the ban (Lee, Gilmore, & Collin, 2004). Specifically, BAT exploited regionality, recognizing that local attitudes toward the national ban might be different than those in Beijing, and they capitalized on provinces’ need for foreign currency. The industry also realized that local interpretations of the legislation could allow for greater flexibility and, in turn, relaxed restrictions (Lee et al., 2004).

Last, in countries with comprehensive or otherwise strict bans, the tobacco industry has used several tactics to combat regulation. One strategy has been to use cross-border advertising to their advantage. In Singapore, where strict tobacco marketing laws have been in place since 1971, the tobacco industry used the absence of regulations in nearby Malaysia to advertise tobacco to Singaporeans: both BAT and PM exploited the “spillover” of Malaysian television into Singapore (Assunta & Chapman, 2004c). Another industry tactic is challenging marketing restrictions in court (e.g., citing violations of free speech). South Africa also has strict bans in place, although they fall just short of comprehensive: the bans do not extend to cross-border advertising, and they restrict, rather than ban, POS advertising. That said, South Africa has continued to strengthen its laws and close loopholes they know the industry might use—for example, by banning viral marketing via text messages. In response, BAT went to court, seeking a declaration that South Africa’s ban was unconstitutional, yet in May 2011 the ban was upheld by the high court as “reasonable and justifiable in a democratic society” (De Lange, 2011; Tumwine, 2011). Still other tactics the industry might use include passing exceptions through the legislature, having a ban overturned, or preventing a country from even signing FCTC.

Ultimately, there are several strategies that may be useful in preempting industry tactics to avoid marketing restrictions. By recognizing the industry’s agility in circumventing bans, countries can try to anticipate its next move and preemptively issue restrictions or bans, before the industry has a chance to mobilize. In its implementation report to the WHO Secretariat, Singapore noted that it preempted the marketing of new and emerging tobacco products (e.g., fruit- or candy-flavored cigarettes, cigarillos, dissolvables) by empowering the health minister to ban these products (WHO, n.d., “Article 16: Progress made in implementing Article 16”). Another strategy is empowering tobacco control organizations to initiate court proceedings against law violators. Niger’s tobacco control law bestowed this right upon nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and in 2007, a tobacco control NGO sued two companies for violating the country’s advertising ban—a move that underscores not only the central role that civil society can play in monitoring and enforcing restrictions but also the role that the judicial system can play in advancing tobacco control efforts (Tumwine, 2011). In addition, it is important for countries to guard against industry influence in the policy-making process. In her keynote address at the 15th World Conference on Tobacco or Health in Singapore, Margaret Chan, Director-General of WHO, emphasized this point: “In some countries, the tobacco industry is pushing for joint government-industry committees to vet or screen all policy and legislative matters pertaining to tobacco control. Don’t fall into this trap. Doing so is just like appointing a committee of foxes to look after your chickens” (WHO, 2012). FCTC Article 5.3 recognizes the industry’s influence over tobacco control policy making, and it will be increasingly important for signatories—especially low- and middle-income signatories—to counter such influence (Lee, Ling, & Glantz, 2012).

Recent Trends: A Move Toward Comprehensive Bans

The past two decades have seen a strengthening of marketing restrictions—encouraged in part by FCTC ratification, with countries moving from weak or limited policies to more comprehensive restrictions (Blecher, 2008). This trend has been particularly pronounced in high-income countries, which historically have had more TAPS restrictions than low- and middle-income nations (Blecher, 2008). Blecher suggested that these bans and, more broadly, comprehensive tobacco control strategies were not as popular in low- and middle-income countries because consumption was still relatively low.

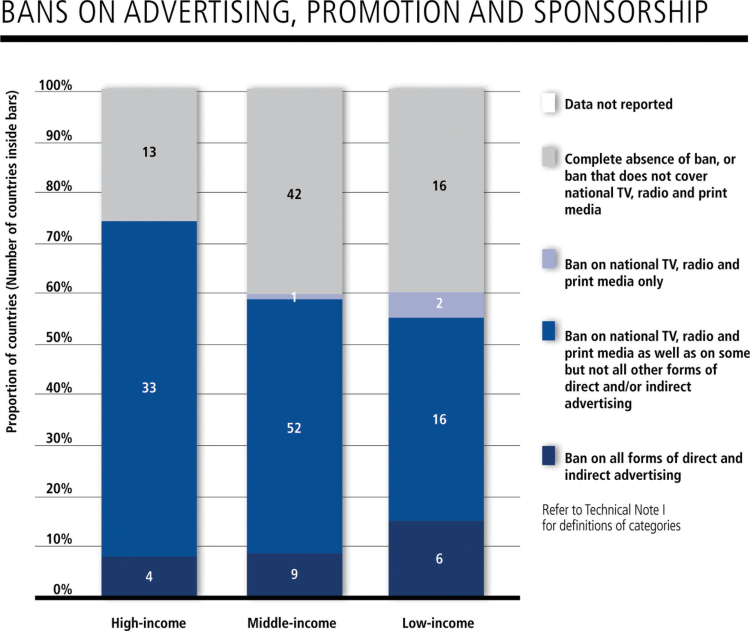

That said, consumption is growing, and there has been an increase in the number of low- and middle-income countries pursuing TAPS bans or restrictions. The 2011 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic indicates that partial bans are more common among high-income countries. Nearly 70% of high-income countries have banned advertising in broadcast and print media, although some direct and indirect advertising remains; in contrast, approximately one half of middle- and low-income countries have enacted such bans (see Figure 1). However, comprehensive bans are more prevalent among low- and middle-income countries (see Figure 1; WHO, 2011), and the reasons for this greater prevalence are worth exploring in future research. For example, upper middle-income Jordan strengthened its restrictions in 2008, clarifying the wording of tobacco control laws and dedicating additional resources to control. The ministry of health trained 35 health promotion coordinators, who educate people about the law, confiscate promotional materials, and facilitate enforcement by initiating judicial proceedings (WHO, 2009). In Asia, another upper middle-income country, Thailand, has had strong tobacco control measures in place for many years—including comprehensive TAPS restrictions—and there is evidence that their well-implemented legislation has contributed to a sharp decline in awareness of tobacco marketing (Yong et al., 2008). As discussed below, the challenge in all countries is whether bans can be successfully implemented to affect tobacco use. If restrictions are not well implemented, the industry may not have to use any of the aforementioned tactics to avoid restrictions; instead, it can simply ignore them and proceed as if regulations did not exist.

Figure 1.

Bans on advertising, promotion, and sponsorship in high-, middle-, and low-income countries.

World Health Organization (2011). Reproduced with permission from the World Health Organization.

FCTC Article 16: Sales to and by Minors

Article 16 Recommendations

Article 16 recommends that Parties prohibit tobacco sales to youth. As with Article 13, this recommendation is supported by a large body of research. First, there is substantial evidence that tobacco companies have targeted and continue to target the youth market (see NCI, 2008, Chapters 5 and 7 for a review; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). Widely used in consumer marketing, targeted strategies include the association of appealing images and themes with the product in question; by purchasing the product, consumers are assumed to subscribe to the associated image. Such images and themes are developed with specific subgroups in mind. In the case of youth, targeted marketing has suggested that cigarette smoking can help satisfy adolescents’ psychological needs, such as peer acceptance, rebelliousness, risk taking, and stress relief (NCI, 2008, Chapter 7). Second, NCI has concluded that, based on the totality of the evidence, tobacco marketing is causally related to tobacco use—a conclusion that is based, in large part, on the many robust and consistent findings in studies linking marketing to adolescent smoking behavior (NCI, 2008, Chapter 7). Last, in addition to controlling youth demand for tobacco via marketing restrictions (Article 13) and antitobacco campaigns (Article 12), it is important to control the supply of tobacco to minors. Research has shown that interventions that successfully disrupt the commercial distribution of tobacco to youth reduce adolescent smoking (DiFranza, 2012).

Supported by this evidence base, the FCTC issued several recommendations to limit minor access to tobacco. These are summarized below and reproduced in full in Table 1.

Implement legislative, executive, and administrative measures to prohibit tobacco sales to minors (age defined by law or as those under 18)

Measures may include (a) requiring that retailers post minor access restrictions at POS and request identification, if age is in doubt; (b) banning direct access to tobacco (e.g., on store shelves); (c) banning tobacco products in the form of candy, toys, or other objects that appeal to youth; and (d) ensuring that vending machines are not accessible to minors

Work to prohibit the distribution of free tobacco products to youth and the general public

Work to prohibit the sale of single cigarettes or small cigarette packs, which increase product affordability for minors

Implement minor access restrictions in conjunction with other FCTC provisions (e.g., marketing restrictions)

Consider prohibiting the introduction of vending machines in the Party’s jurisdiction, or a total ban on vending machines

Institute penalties against sellers and distributors who violate minor access regulations

Implement measures to prevent the sale of tobacco by minors

Tobacco Industry Tactics to Avoid Minor Access Restrictions

Historically, the tobacco industry has attempted to undermine minor access laws, just as it has tried to undermine marketing restrictions—and it has used similar tactics to combat both types of regulations. Although companies claim that they oppose the sale of tobacco to minors, research has shown that they have worked to prevent the enforcement of underage sales laws. One strategy they have used is preempting stronger legislation by advocating self-regulation. During the early 1990s, as local-level minor access legislation was gaining ground in the United States, the Tobacco Institute (1990) announced that it would help to curb youth access by working with retailers and supporting new state laws. However, the laws that it supported would have preempted and overturned existing efforts that were proving to be effective (DiFranza & Brown, 1992), such as police compliance checks with assistance from underage buyers (Jason, Ji, Anes, & Birkhead, 1991). Additionally, research showed that the Institute’s “It’s the Law” campaign—which was billed as an effort to help retailers comply with state laws by distributing signs, decals, and educational materials—failed to reduce the sale of tobacco products to minors, thus demonstrating that self-regulation was not a viable alterative to enforced legislation (DiFranza & Brown, 1992).

The “It’s the Law” campaign underscores another tactic used by the industry: developing “youth smoking prevention” efforts that are, in fact, a means of industry self-preservation. By analyzing U.S. tobacco documents made public through the MSA, researchers have shown that the industry’s ubiquitous “We Card” program was created for two reasons: to improve the industry’s image, and to undermine regulation and the enforcement of existing laws (Apollonio & Malone, 2010). In fact, documents suggested not only that the industry did not intend for the program to be effective but that it has not reduced sales to minors, despite industry claims to the contrary (Apollonio & Malone, 2010). These findings are particularly concerning, as similar programs have been developed in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Latin America (Imperial Tobacco Canada, 2012; Operation ID UK, n.d.; Sebrié & Glantz, 2007).

Tobacco retailers also have filed legal challenges to restrictions, and it is possible that retailers have received industry support in such litigation (DiFranza & Rigotti, 1999). DiFranza and Rigotti (1999) describe a case in which a retailer facing a U.S. $100 civil fine hired an attorney to mount a vigorous defense, which questioned the “chain of possession” of the evidence (i.e., a cigarette pack). The authors note that “[the] legal expense for this defence [sic] cannot be financially justified to avoid a $100 fine and raises the suspicion that this undertaking was financed by an entity with an interest in weakening enforcement efforts” (DiFranza & Rigotti, 1999, p. 154).

To preempt industry efforts to avoid minor access restrictions, countries can look to the substantial body of research documenting the effects of interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors. Although prior reviews questioned whether these interventions do, in fact, reduce youth smoking, a recent comprehensive review of the literature concluded that interventions that successfully disrupt the sale of tobacco to youth can be expected to reduce youth smoking (DiFranza, 2012). DiFranza (2012) argues that prior reviews did not distinguish between interventions that failed to disrupt the commercial distribution of tobacco (e.g., those that enacted laws but did not enforce them, those that relied entirely on merchant education) and those that successfully disrupted sales—and, in so doing, created a “false controversy” about the effectiveness of youth access interventions. He further notes that if a sales-to-minors law is challenged in court, a government might be expected to demonstrate that the law should benefit public health. Thus, this systematic review of youth access interventions may prove critical in thwarting tobacco industry interference with minor access legislation. Ultimately, though, the industry may not need to challenge such legislation because there is evidence that, in many countries, minor access laws are poorly enforced (see next section).

FCTC Articles 13 and 16: Implementation Challenges

A central challenge to FCTC implementation is the enforcement of existing marketing and sales-to-minors regulations. Countries have struggled with enforcement for various reasons. For example, some have a limited capacity for enforcement. The India Tobacco Control Act restricts the size of POS displays, and yet these restrictions appear to be ignored by the industry with little to no consequence (Sinha et al., 2008). In Thailand, enforcing minor access laws has proven difficult for two main reasons: the officials appointed to enforce the Tobacco Product Control Act are public health officers who have many other responsibilities, and the fines for violators are minimal (Sangthong, Wichaidit, & Ketchoo, 2012). Elsewhere, enforcement has been complicated by the existence of an informal economic sector. Guatemalan law bans the sale of single cigarettes and packs with fewer than 20 cigarettes, yet a recent surveillance study found that single-cigarette sales were highly prevalent among street vendors (de Ojeda, Barnoya, & Thrasher, 2012). Restricting such sales and, in turn, enforcing Article 16 remains challenging, because these vendors are not recognized or regulated by the legal system. The illegal sale of singles is also prevalent in other low- and middle-income countries, such as Mexico (Rodríguez-Bolaños et al., 2010; Thrasher, Villalobos, Barnoya, Sansores, & O’Connor, 2011), as well as in low-income areas of high-income countries, such as the United States (Stillman et al., 2007).

As previously discussed, the tobacco industry’s influence on government officials also can serve as a barrier to enforcement. Although Russia ratified the FCTC in 2008, members of parliament subsequently passed a new national standard for tobacco products that contradicts the framework. The legislation, which was drafted by a tobacco industry lobbyist and endorsed by several parliament members, allows the terms “light” and “mild” to be used on tobacco packs (Vlassov, 2008). Although the Russian government continues to advocate a comprehensive TAPS ban (Parfitt, 2010), the fact that the tobacco industry is able to participate in the legislative process can undermine the enforcement of existing policies and influence the implementation of new regulations. A related enforcement issue is conflicts of interest. In China, the government department that handles the administration, production, and sale of tobacco products is also responsible for tobacco control, so implementing FCTC provisions independent of tobacco industry influence is a challenge (Lv et al., 2011). In addition, tax revenues from tobacco sales might deter countries from passing strict regulation laws.

Some of these examples illustrate the tobacco industry’s agility at circumventing marketing regulations. Because comprehensive bans are not an option for all countries due to constitutional and legal constraints, the industry’s circumventing practices are a central Article 13 implementation barrier. We have seen that countries’ efforts to ban marketing have prompted the industry to redirect resources to other vehicles and venues. Current trends in redirection include sponsoring events in social and entertainment venues. With increasing media marketing restrictions, high-, middle-, and low-income countries have seen promotions in bars, cafes, and nightclubs (e.g., Biener, Nyman, Kline, & Albers, 2004; Gilpin, White, & Pierce, 2005; Sepe, Ling, & Glantz, 2002; Shahrir et al., 2011). Promotions include free cigarettes, drink offers or discounts, event sponsorships, and decoration funding (Shahrir et al., 2011). Additionally, in some countries tobacco product placement in entertainment media is widespread. Given substantial evidence that exposure to movie smoking is causally related to adolescent smoking initiation (NCI, 2008)—including recent evidence among youth (Sargent & Hanewinkel, 2009; Thrasher et al., 2009) and adults (Viswanath, Ackerson, Sorensen, & Gupta, 2010) from countries outside the United States—limiting product placement and other smoking imagery in movies, television programs, and other entertainment media has become a priority. For example, India recently strengthened its marketing regulations by prohibiting product placement in new films and programs; scenes with product brands will be masked or blurred in older films. It also prohibited promotional materials from showing tobacco products or their use, and required strong editorial justification for displaying tobacco products in films or programs (“India – New regulations on depictions of tobacco products in films and on TV,” 2011). In the United States, films have seen a decline in tobacco portrayals—due, in part, to advocacy efforts and MSA rules prohibiting industry influence—yet there is evidence that this downward trend may be reversing (Glantz, Iaccopucci, Titus, & Polansky, 2012).

Innovations in tobacco products are complicating the issue of both marketing and minor access restrictions. Products such as waterpipes or hookahs are increasingly popular among youth, likely because of their affordability, their flavoring, and the social aspect of waterpipe smoking (Martinasek, McDermott, & Martini, 2011). In some countries, waterpipe consumption is more prevalent than cigarette smoking: 2005 Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data showed that among Lebanese students, waterpipe smoking rates were 4 times higher than cigarette smoking rates (Saade, Warren, Jones, Asma, & Mokdad, 2008). The products are consumed in places such as hookah bars or cafes, which may or may not be covered under current marketing regulations. Because these bars are particularly popular with youth and may offer new tobacco marketing opportunities, scholars have called for waterpipes and other products to be included under tobacco control purview (Cobb, Ward, Maziak, Shihadeh, & Eissenberg, 2010; Maziak, 2011).

POS advertising is also an FCTC implementation challenge. Although some countries, such as Ukraine and the United Kingdom, have passed legislation to ban all POS activity (Bonner, 2012; “Tobacco displays at the point of sale,” 2012), this form of indirect marketing is still prevalent, even in countries with strict marketing restrictions. Researchers have called for POS advertising bans, particularly given consistent evidence that POS exposure is linked to youth smoking initiation (Henriksen, Schleicher, Feighery, & Fortmann, 2010; Paynter & Edwards, 2009). In the United States, the FSPTCA includes some POS restrictions designed to protect youth (e.g., banning outdoor POS advertising near schools and playgrounds), but these remain under FDA review (Luke, Ribisl, Smith, & Sorg, 2011). Similarly, India recently passed legislation that strengthens antitobacco messaging at POS sites. Images of cancer caused by smoking now must accompany the age restriction signs in retail stores, in an effort to deter minors from purchasing tobacco (“India – Mandatory picture to be included in point-of-sale displays,” 2011). Elsewhere, though, the tobacco industry continues to provide custom displays to retailers to market to youth and the general public (“Implementing the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: A civil society report – Botswana,” 2012). For policy makers to successfully advocate POS restrictions, more research is needed on the long-term consequences of decreased POS activity (e.g., reduction in smokers’ cravings and urges, given fewer external smoking cues) (Henriksen, 2012).

Another implementation challenge is cross-border activity, both in the context of marketing and minor access. Kuber Khaini, a tobacco product manufactured in India, has flooded the Botswana market. It is labeled as a “mouth freshener” rather than a tobacco product, and thus is widely available to youth (“Implementing the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: A civil society report – Botswana,” 2012). Similarly, cross-border advertising has proven challenging even for countries with strict marketing regulations. Although TAPS has been banned in the Seychelles for years, there is no regulation of content that is not produced locally (e.g., imported newspapers, magazines, cable television, and Internet content; Viswanathan, Warren, Jones, Asma, & Bovet, 2008). To address cross-border advertising, Kenyon and Liberman (2006, p. 1) have recommended that “a multilayered approach—which includes formal law and regulation, monitoring and enforcement practices, education, and international cooperation—be applied in relation to three categories of actors: advertising producers and their agents, content providers, and technological intermediaries, if the aims of the FCTC are to be met.” Although some countries have taken steps to curtail such advertising (e.g., Panama; WHO, 2009), this remains a daunting task—particularly in the new media environment. There is evidence that tobacco companies are increasingly using the Internet and social media to market their products. The industry has used open source marketing, soliciting public input on cigarette packaging design and flavors (Freeman & Chapman, 2009), and researchers have documented the presence of protobacco content on YouTube (Elkin, Thomson, & Wilson, 2010). In addition, a recent study found that industry employees have used Facebook to market tobacco—and these are employees from countries that have ratified the FCTC (Freeman & Chapman, 2010). How countries can regulate such practices, particularly if a Web site’s server is housed overseas, is likely to be an ongoing challenge.

Lastly, additional implementation obstacles include unclear language about who enforces policies (e.g., local health department officials or police); the difficulty of identifying marketing violations, given the sheer amount of marketing coupled with scarce enforcement personnel; and the time required to bring closure to violations once the tobacco industry begins to fight charges (Lieberman, 2004; Roeseler, Feighery, & Boley Cruz, 2010).

FCTC Articles 13 and 16: Implementation and Research Priorities

This review suggests that there are several challenges in implementing the provisions of Articles 13 and 16. Therefore, it is critical to consider how these barriers can be addressed, and what research is necessary to support such efforts. Although a solid evidence base underpins the FCTC’s call for comprehensive TAPS bans and minor access restrictions, there is substantially less research on how best to implement these restrictions.

This is not to say that there have not been efforts to encourage and track implementation. WHO’s MPOWER package offers technical assistance to nations aiming to implement FCTC provisions, and it includes six effective tobacco control strategies: monitoring tobacco use and prevention polices; protecting from tobacco smoke; offering help to quit tobacco use; warning about the dangers of tobacco; enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; and raising taxes on tobacco (WHO, 2011). Enforcement, or the “E” of MPOWER, is particularly germane to this paper. In addition, FCTC Article 21 calls upon signatories to submit periodic implementation reports to the Conference of the Parties, and in 2011, WHO launched an FCTC implementation database to make these data publicly available (WHO, n.d.). The database is searchable by party or FCTC article. It contains quantitative results (e.g., tallies of the number of parties implementing an article), as well as qualitative feedback (e.g., challenges that parties have encountered during implementation). The qualitative data could be particularly useful—for example, if a researcher were to synthesize the data, distill important themes, and contact specific parties to obtain additional insight into implementation barriers.

This research idea and others are discussed below. We organize the implementation and research priorities into four broad categories: (a) policy enactment and enforcement, (b) human capital expertise, (c) effects of FCTC marketing and youth access policies, and (d) knowledge exchange and transfer among signatories.

Policy Enactment and Enforcement

Although FCTC is clear on provisions that countries should enact to prevent tobacco marketing and sales to minors, it is less clear on what is required to implement such restrictions—especially given different laws and regulations across countries. Policy implementation research needs fall into three areas: (a) how treaty signatories are defining the provisions and customizing them to their country’s legal environment, (b) the effects of such variation on provision adoption, and (c) local challenges in the implementation of marketing and youth access restrictions.

In considering Article 13’s implementation, the example from Russia is instructive. Despite the fact Russia signed and ratified the treaty, members of parliament passed new legislation—reportedly drafted by a tobacco industry lobbyist—that allows the use of words such as “light” and “mild” on cigarette packages. When industry can participate in the legislative process, it has the potential to deter successful enactment of FCTC provisions. Industry influence aside, some countries may not have the legal infrastructure to support policy enactment and enforcement. For example, Owusu-Dabo, McNeill, Lewis, Gilmore, and Britton (2010) identified implementation challenges in Ghana through semistructured interviews with members of the national steering committee for tobacco control. Researchers learned that a tobacco bill has been drafted but not implemented, and although the reasons for delay were not entirely clear, barriers included the absence of a legal framework to enforce tobacco control measures and, perhaps more importantly, a lack of political will.

There have been calls for stronger policies and greater enforcement—for example, in China (Li et al., 2009), Asia at large (Sirichotiratana et al., 2008), and Albania (Zaloshnja, Ross, & Levy, 2010)—yet few specific solutions have been offered. The 2009 WHO report highlights some examples of implementation success (e.g., Jordan, Madagascar), but overall there is a need for more empirical work on how to enforce marketing restrictions. There are several questions that need answering: How does a country know if a specific restriction has high compliance? What are the effects of compliance rates? Who enforces restrictions and how? What are the penalties for nonenforcement? One promising research strategy for answering these questions is detailed implementation case studies. Owusu-Dabo et al.’s study provides a useful illustration. In addition, Thrasher and colleagues (2008) reviewed the challenges and opportunities for FCTC policy implementation in Mexico, taking into account the legal, sociocultural, and political economic context of the country. In fact, Singapore, in its implementation report to the WHO Secretariat, called for these types of data: “[priorities include] facilitation of case study sharing for the actual implementation of FCTC, inclusive of overcoming challenges” (WHO, n.d., “Article 22 & 26: Priorities and comments: Details on specific gaps”). Such detailed studies, coupled with syntheses of existing data sources (e.g., qualitative reports in the WHO FCTC implementation database), will allow researchers and policy makers to discern implementation best practices. Countries, in turn, can consider which strategies may be most successful, given their nation’s capacity for media regulation, its constitutional provisions on commercial speech, its legal environment, and other important factors.

Although a premium should be placed on developing effective implementation strategies, it is equally important to understand the determinants of implementation. At the time of the WHO report’s 2011 publication, 74 parties had few or no TAPS restrictions. Although constitutional constraints could be a barrier for some nations, it is important to understand why countries without such constraints are not taking steps to implement a comprehensive ban. In addition, for those countries whose constitutions do preclude a comprehensive ban, we need recommendations for which ban components may be most important in curbing tobacco use. For example, is it more important for such nations to push POS restrictions, or Internet marketing restrictions? Assessing the weight and importance of these components may help nations decide how to proceed, recognizing that impartial bans, though ineffective, are preferable to no restrictions at all.

Countries implementing Article 16 also have met enforcement challenges. As previously noted, Thailand has had difficulty enforcing minor access laws because public health officials who are responsible for enforcement are overcommitted; in addition, fines for violators are very low (Sangthong et al., 2012). Guatemala, on the other hand, has struggled to enforce its minor access law because street vendors remain a major source of single cigarettes, and these vendors are not regulated (de Ojeda et al., 2012). Just as implementation case studies may prove useful to countries implementing Article 13, so, too, may they be helpful to those seeking to enact and enforce Article 16’s provisions.

Additionally, enforcement insights may be gleaned from studies that have considered the effects of interventions designed to reduce youth access. DiFranza (2012) reviews the interventions that successfully disrupted the sale of tobacco to minors, including efforts in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands. At least one enforcement tactic was distilled during the course of his review: “all successful enforcement programmes [sic] employ routine inspections involving test purchases by minors” (DiFranza, 2005, 2012, p. 441). Additionally, DiFranza argues that, in the United States, such enforcement is inexpensive, is often paid for using license fees, is efficient in terms of the cost per year of life saved, and could be paid for using a 1-cent tax on cigarette packs (DiFranza, 2012; DiFranza, Peck, Radecki, & Savageau, 2001). Whether such cost-effectiveness translates in other countries should be evaluated in future research.

Human Capital Expertise

Despite the importance of examining the effects of TAPS and imposing restrictions on marketing and youth access, little is known about the availability of human capital expertise for these activities. Building capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income nations, to examine TAPS effects and impose regulations may be one of the more urgent tasks if the FCTC is to succeed. Countries that have built infrastructures to implement and monitor regulation could be used as models for other nations. For example, California’s monitoring efforts (Roeseler et al., 2010)—which involve population-based telephone and in-school surveys to track exposure to and beliefs about industry marketing, as well as observational surveys of marketing in sponsored events and the retail environment—and Jordan’s enforcement model, with its cadre of trained health promotion coordinators (WHO, 2009), could be adapted and introduced in other countries. In Hong Kong, tobacco control NGOs have performed compliance checks to see if retailers are abiding by youth access laws (Kan & Lau, 2008, 2010). Minors were recruited and trained to make test purchases, and results showed that additional enforcement and monitoring is necessary. Other countries could replicate such surveillance efforts.

In addition, in some countries, tobacco control advocates have collaborated with the media to publicize tobacco marketing, youth access, and other restrictions in an effort to raise awareness and influence public opinion. China and Indonesia have worked with the media to scrutinize tobacco industry practices, such as sponsorship of sporting events and high-profile concerts (WHO, 2011). India has underscored the need to raise public awareness of and support for tobacco control efforts, thereby recognizing the valuable role that civil society can play in monitoring and reporting tobacco control violations (“Implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in India,” 2010). These media advocacy and community mobilization strategies could be adopted by other nations.

Importantly, there have been recent efforts to build capacity for tobacco control in some nations. The Framework Convention Alliance (FCA), a civil society alliance of more than 350 organizations from more than 100 nations, monitors FCTC implementation (Mamudu & Glantz, 2009). Similar to WHO, FCA tracks implementation through a number of mechanisms. Through the FCA FCTC Monitor, the alliance tracks and evaluates FCTC implementation at the national level. This implementation monitoring report is disseminated at the Conference of the Parties (FCA, 2007). In addition, the Tobacco Watch is a shadow report that tracks treaty compliance: the FCA’s NGO members not only contribute to the Watch but they also can apply for grants to conduct shadow reporting within their countries (Bostic, 2012). In 2010, FCA provided grants to 12 NGO partners from low- and middle-income countries, including Brazil, Ghana, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Syria, and in 2011, it awarded grants to Benin, Botswana, Cambodia, and Nigeria, among others. The nations’ shadow reports, which are available online (FCA, 2011, 2012), describe NGOs’ efforts to gather data on FCTC violations, including marketing and youth access violations. By encouraging such surveillance and enforcement within Parties, FCA is helping member nations to build capacity for tobacco control.

Indeed, researchers have argued that strong tobacco advocacy organizations and other NGOs are central to implementation success (Mehl, Wipfli, & Winch, 2005; Sparks, 2010). Not surprisingly, then, FCA is not the only group investing in such organizations. The Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use has supported NGOs and other groups in more than 40 countries. Moreover, WHO has actively supported both FCA and the Bloomberg Initiative, providing technical assistance to both organizations through its regional offices. Informal transnational advocacy networks, such as Latin America’s Coalición Latinoamericana Coordinadora para el Control del Tabaco, also have been active in some regions, sharing ideas, experiences, and materials to promote FCTC implementation (Champagne, Sebrié, & Schoj, 2010). In the United States, the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center has released several funding opportunity announcements that underscore a growing interest in investment in human capital through training. Some have argued that if the United States were to ratify the FCTC, it would play a crucial role in global tobacco control efforts by encouraging greater funding and providing technical assistance and support (Bollyky & Gostin, 2010). Other countries, such as Australia, have already taken such steps by providing financial support for FCTC implementation in low- and middle-income nations (Taylor, 2011). Taken together, such funding initiatives would support additional research on how best to invest in human capital to implement FCTC policies, and how such recommendations might vary across countries.

Effects of FCTC Marketing and Youth Access Policies

Monitoring and enforcing FCTC policy, and building capacity for such enforcement efforts, should have tangible tobacco-related outcomes. Yet, whether FCTC implementation produces the intended results is an empirical question. As parties work toward implementation, it is important that they build infrastructure to evaluate the effects of FCTC policies. Article 20 calls for surveillance, and the WHO’s MPOWER package offers guidance for such monitoring (WHO, 2011). WHO recommends that nations conduct surveys on tobacco use and tobacco control policy implementation, either as standalone tobacco surveys or as part of general health surveys. Consistent with this recommendation, some countries have analyzed GYTS data vis-à-vis their tobacco control efforts to evaluate the success of these efforts (Erguder et al., 2008; Saade et al., 2008; Sirichotiratana et al., 2008; Viswanathan et al., 2008). For example, in Turkey almost half of current youth smokers reported that they usually bought tobacco in stores, and of these nearly 9 out of 10 reported that they had not been refused purchase because of their age (Erguder et al., 2008). Therefore, the authors concluded that Turkey requires better enforcement of its minor access law. Additionally, survey surveillance efforts should include questions on TAPS exposure, with a specific focus on vulnerable populations such as youth. Some nations have already begun assessing exposure following FCTC implementation (e.g., Thailand; Yong et al., 2008). Moving forward, assessing whether marketing restrictions are tied to less tobacco use will be important.

The effects of the new media environment on enforcement and tobacco prevalence also warrant urgent attention by researchers and policy makers. The FCTC’s recommendations on marketing are taking place at a time of major social and technological change, particularly in new information and communication technologies such as the Internet. We previously described the challenge of controlling cross-border advertising in this new media environment. It is not clear how provisions regarding cross-border advertising can be implemented when there is increasing marketing of cigarettes through the Internet and social media, coupled with growing Internet access among the world’s populations. What is clear is that social media such as Facebook and YouTube have been used to promote tobacco (Elkin et al., 2010; Freeman & Chapman, 2009, 2010), easily circumventing local bans and complicating what it means to successfully implement Article 13’s provisions.

Lastly, there is a large body of evidence showing the differential impact of marketing across population subgroups, including youth, women, and racial/ethnic minorities (see NCI, 2008, Chapter 5 for a review). Currently, POS advertising in the United States and elsewhere has the potential to differentially affect vulnerable subgroups. Research has shown that POS activity is more prevalent in low-income and minority communities, and that youth living in such communities may be at greater risk for advertising exposure and, in turn, smoking initiation (Feighery, Schleicher, Boley Cruz, & Unger, 2008; John, Cheney, & Azad, 2009; Seidenberg, Caughey, Rees, & Connolly, 2010; Siahpush, Jones, Singh, Timsina, & Martin, 2010). There is also evidence that tobacco companies are continuing their efforts to grow the U.S. urban Black menthol segment through retail signage, price discounts, and promotions associated with a hip-hop lifestyle (Boley Cruz, Wright, & Crawford, 2010). Given these concerning POS trends, coupled with growing concerns about tobacco-related disparities (Fernander, Resnicow, Viswanath, & Pérez-Stable, 2011), additional research on the differential effects of FCTC policy implementation on population subgroups is warranted. Inequalities may manifest at two levels: differences across countries in adopting, customizing, implementing, and enforcing FCTC provisions, and the differential impact of FCTC implementation on population subgroups within countries. It is critical to document both types of inequalities.

Knowledge Exchange and Transfer Among Signatories

Another significant priority—underscored in FCTC Articles 20, 21, and 22—is to understand how knowledge exchange and transfer can be fostered and, in turn, facilitate the effective implementation of FCTC Articles 13 and 16. Knowledge exchange efforts may focus on three broad areas. First, it is clear from our review that even among signatories to the Convention, there is considerable variation in their interpretation, implementation, and enforcement of FCTC mandates. While it is inevitable that different countries will adapt the articles to suit local culture, laws, and needs, it is becoming clear that the net effect in some countries is dilution of treaty provisions, working against the original aims. From a knowledge transfer perspective, the articles constitute the “core” elements or the minimum that is required to reduce demand and supply, but given the reality of implementation, it is necessary to help countries to “package” the treaty provisions for successful adaption to local conditions without diluting the core provisions. This is easier said than done, thus warranting research on how the “core” and “package” elements of the treaty are being adapted and with what effects.

Second, the effectiveness of existing mechanisms for knowledge exchange requires more research. This includes exploring how to make effective use of the FCA as a network to exchange information. If FCA is not the optimal body, do we need alternative structures to facilitate knowledge exchange, including materials such as case studies, research findings, and training manuals to promote implementation or skills transfer (e.g., how to conduct compliance checks)?

Finally, given the global nature of tobacco industry operations and cross-border flow of protobacco information, formal and informal approaches are necessary to track tobacco industry activities. Monitoring (the “M” of MPOWER) tobacco industry activities and its efforts to undermine the treaty, and sharing that information broadly among the signatories, may counter the industry’s current diffused “divide and conquer” approach. Coordinated cross-country research and surveillance efforts, such as the Global Adult Tobacco Survey and the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project, may prove useful to such knowledge exchange and transfer activities.

Summary

This paper reviewed the evidence base for FCTC Articles 13 and 16, and highlighted some of the major challenges in implementing the provisions. Identifying what is required to successfully implement the FCTC mandates is an important area of research for tobacco control. To summarize, future inquiry should address the following issues:

Countries vary in their TAPS bans, with some implementing no bans, some imposing partial bans, and some imposing complete bans. While the constitutional restrictions of a given country could be one explanation for these differences, other factors that lead to such variation remain unclear and are worth exploring in future research.

Some countries have enjoyed a degree of success in implementing FCTC provisions, while many others have not, despite having ratified the treaty. Little is known about the reasons why countries have not implemented the mandates.

It is also unclear how recommendations should be codified and enforced. Detailed case studies on FCTC implementation successes and failures will be extremely valuable to global tobacco control efforts.

There is a need for scientific capacity within countries to monitor tobacco industry activities and document any violation of tobacco control laws. Research is required to understand the human capital needs for surveillance and implementation of FCTC provisions.

National infrastructure to monitor people’s exposure to tobacco-related marketing, analyze the effects of such exposure on tobacco consumption, and ensure compliance with minor access laws is urgently needed.

It is critical to understand the role of new media such as the Internet and social media in promoting or circumventing tobacco control efforts.

While there are lessons to be learned from global tobacco control efforts to date, innovations in tobacco products are complicating the issue of tobacco marketing and youth access restrictions. Innovations such as waterpipes or hookahs and e-cigarettes are being promoted, and there is a widespread perception that they may be less harmful. Tackling the impact of such new tobacco products will be increasingly important, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

In light of growing POS activity in the United States and other countries—and given the potential for such marketing to differentially affect low-income and minority youth—it is important to identify ways that countries can implement effective POS restrictions, particularly if a comprehensive ban is not feasible.

We need more research on how to translate knowledge of successful marketing and youth access restrictions and interventions into tobacco control policy and practice. There has been considerable research on the impact of marketing restrictions and minor access interventions (e.g., see DiFranza, 2012; NCI, 2008); what is lacking is research on how to successfully translate this knowledge into practice in different national contexts. Knowledge translation research and knowledge exchange efforts will contribute to effective FCTC implementation.

Although we identified these implementation and research priorities following a thorough review of the published literature, policy and implementation reports, press releases, and media coverage, there may be other important research needs that are not discussed here. Future efforts should address not only the priorities set out in this paper but also identify additional issues and factors relevant to the implementation of Articles 13 and 16.

CONCLUSION

The FCTC, the first public health treaty of its kind, has the potential to have a tremendous impact on global population health, offering us a unique opportunity to reduce mortality and morbidity. The treaty proposes a comprehensive legal and regulatory framework to affect tobacco use, but its success relies on effective implementation of Articles 13 and 16. Our review underscores the challenges that many countries historically have faced in implementing and enforcing tobacco marketing and youth access restrictions, although there is evidence that meaningful successful restrictions are possible. Future research should identify best practices in policy implementation; this might include identifying challenges that different countries have faced in implementation, as well as solutions devised by different countries in overcoming those challenges. A speedy exchange of knowledge will likely enhance the successful implementation of FCTC, thereby reducing the effects of the global tobacco use epidemic.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Tobacco Disparities Research Network (jointly funded by the National Cancer Institute and American Legacy Foundation), the Harvard School of Public Health’s Lung Cancer Disparities Center (3 P50-CA148596), and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (P30-CA006516). Funding support for RHN was also provided through the National Cancer Institute by the Harvard Education Program in Cancer Prevention and Control (5 R25-CA057711).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Rachel Faulkenberry McCloud and Dave Rothfarb at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for their assistance with manuscript preparation. Portions of this work were presented at the 13th Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco-Europe, Antalya, Turkey, September 8–11, 2011.

REFERENCES

- Albright C. L., Altman D. G., Slater M. D., Maccoby N. (1988). Cigarette advertisements in magazines: Evidence for a differential focus on women’s and youth magazines. Health Education Quarterly, 15, 225–233 doi:10.1177/109019818801500207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegre M. (2003). We’ve come a long way baby (or have we?): Banning tobacco advertising and sponsorship in the European Union. Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 26, 157–170 Retrieved from http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol26/iss1/9 [Google Scholar]

- Apollonio D. E., Malone R. E. (2010). The “We Card” program: Tobacco industry “youth smoking prevention” as industry self-preservation. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1188–1201 doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.169573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assunta M., Chapman S. (2004a). A mire of highly subjective and ineffective voluntary guidelines: Tobacco industry efforts to thwart tobacco control in Malaysia. Tobacco Control, 13(Suppl. 2), ii43–ii50 doi:10.1136/tc.2004.008094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assunta M., Chapman S. (2004b). The tobacco industry’s accounts of refining indirect tobacco advertising in Malaysia. Tobacco Control, 13(Suppl. 2), ii63–ii70 doi:10.1136/tc.2004.008987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assunta M., Chapman S. (2004c). “The world’s most hostile environment”: How the tobacco industry circumvented Singapore’s advertising ban. Tobacco Control, 13(Suppl. 2), ii51–ii57 doi:10.1136/tc.2004.008359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer R., Gostin L. O., Javitt G. H., Brandt A. (2002). Tobacco advertising in the United States: A proposal for a constitutionally acceptable form of regulation. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287, 2990–2995 doi:10.1001/jama.287.22.2990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L., Nyman A. L., Kline R. L., Albers A. B. (2004). Adults only: The prevalence of tobacco promotions in bars and clubs in the Boston Area. Tobacco Control, 13, 403–408 doi:10.1136/tc.2004.007468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blecher E. (2008). The impact of tobacco advertising bans on consumption in developing countries. Journal of Health Economics, 27, 930–942 doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum A. (1991). The Marlboro Grand Prix: Circumvention of the television ban on tobacco advertising. New England Journal of Medicine, 324, 913–917 Retrieved from www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199103283241310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boley Cruz T., Wright L. T., Crawford G. (2010). The menthol marketing mix: Targeted promotions for focus communities in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12(Suppl. 2), S147–S153 doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollyky T. J., Gostin L. O. (2010). The United States’ engagement in global tobacco control: Proposals for comprehensive funding and strategies. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304, 2637–2638 doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner B. (2012, March 13). Yanukovych signs law to ban tobacco advertising Retrieved from www.kyivpost.com/content/ukraine/yanukovych-signs-law-to-ban-tobacco-advertising-124190.html

- Bostic C. (Ed.). (2012). Tobacco watch: Monitoring countries’ performance on the global treaty Framework Convention AllianceRetrieved from http://www.fctc.org/images/stories/Tobacco_Watch_2012_ENG.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Brief report on the implementation of the FCTC’s core articles in Cambodia up to March 2012 (2012). Framework Convention Alliance shadow report Retrieved from www.fctc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=759:latest-shadow-reports-focus-on-national-priorities&catid=245:implementation-monitoring&Itemid=249

- Brown M. (2012, June 20). Child smokers prompt Indonesia legal case Retrieved from www.abc.net.au

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (2012). Global epidemic: Indonesia Retrieved from http://global.tobaccofreekids.org/en/global_epidemic/indonesia/

- Celebucki C. C., Diskin K. (2002). A longitudinal study of externally visible cigarette advertising on retail storefronts in Massachusetts before and after the Master Settlement Agreement. Tobacco Control, 11(Suppl. 2), ii47–ii53 doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne B. M., Sebrié E., Schoj V. (2010). The role of organized civil society in tobacco control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Salud Pública de México, 52(Suppl. 2), S330–S339 doi:10.1590/S0036-36342010000800031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C., Ward K. D., Maziak W., Shihadeh A. L., Eissenberg T. (2010). Waterpipe tobacco smoking: An emerging health crisis in the United States. American Journal of Health Behavior, 34, 275–285 doi:10.5993/AJHB.34.3.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lange I. (2011, May 22). Tobacco ads ban upheld Retrieved from www.citizen.co.za

- De Ojeda A., Barnoya J., Thrasher J. F. (2012). Availability and costs of single cigarettes in Guatemala. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza J. R. (2005). Best practices for enforcing state laws prohibiting the sale of tobacco to minors. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 11, 559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza J. R. (2012). Which interventions against the sale of tobacco to minors can be expected to reduce smoking? Tobacco Control, 21, 436–442 doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza J. R., Brown L. J. (1992). The Tobacco Institute’s “It’s the Law” campaign: Has it halted illegal sales of tobacco to children? American Journal of Public Health, 82, 1271–1273 doi:10.2105/AJPH.82.9.1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza J. R., Peck R. M., Radecki T. E., Savageau J. A. (2001). What is the potential cost-effectiveness of enforcing a prohibition on the sale of tobacco to minors? Preventive Medicine, 32, 168–174 doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.0795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza J. R., Rigotti N. A. (1999). Impediments to the enforcement of youth access laws. Tobacco Control, 8, 152–155 doi:10.1136/tc.8.2.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkin L., Thomson G., Wilson N. (2010). Connecting world youth with tobacco brands: YouTube and the Internet policy vacuum on Web 2.0. Tobacco Control, 19, 361–366 doi:10.1136/tc.2010.035949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erguder T., Çakir B., Aslan D., Warren C. W., Jones N. R., Asma S. (2008). Evaluation of the use of Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) data for developing evidence-based tobacco control policies in Turkey. BMC Public Health, 8(Suppl. 1), S4 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-S1-S4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen M., Mackay J., Ross H. (2012). The Tobacco Atlas (4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; New York, NY: World Lung Foundation; Retrieved from www.TobaccoAtlas.org [Google Scholar]